Background

Stigma in mental illness is a complex construct that reflects problems in knowledge (ignorance), attitude (prejudice) and behavior (discrimination) toward people with mental disorders, their families and caregivers (Goffman, Reference Goffman1963; Link and Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam and Sartorius2007; Fox et al., Reference Fox, Earnshaw, Taverna and Vogt2018). Stigma against people with mental illnesses is well established as a major contributing factor for poor treatment and disease outcomes. Poor outcomes associated with stigma include low job prospects (Luciano and Meara, Reference Luciano and Meara2014), poorer prospects of social relationships such as marriage (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Miller, Jin, Sampson, Alonso, Andrade, Bromet, De Girolamo, Demyttenaere, Fayyad, Fukao, Galaon, Gureje, He, Hinkov, Hu, Kovess-Masfety, Matschinger, Medina-Mora, Ormel, Posada-Villa, Sagar, Scott and Kessler2011), increased risk for comorbidities (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Hwang, Sampson and Kessler2010), lower quality of life and premature mortality compared to the general population (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Banerjee, Leese and Huxley2007). Globally, less than half of the people with mental disorders receives minimally adequate and evidence-based care (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Maj, Flisher, De Silva, Koschorke, Prince and Zonal2010) in part because of stigma. These poor outcomes are partly attributed to ignorance about the etiology of mental disorders as well as prejudicial attitudes and discriminatory behavior by the general public and care providers (Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Noblett, Parke, Clement, Caffrey, Gale-Grant, Schulze, Druss and Thornicroft2014). Conceptual models of stigma posit that poor health outcomes for people with mental illness occur through negative emotional responses and behaviors such as fear of seeking help (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko, Bezborodovs, Morgan, Rusch, Brown and Thornicroft2015; Luitel et al., Reference Luitel, Jordans, Kohrt, Rathod and Komproe2017; Zewdu et al., Reference Zewdu, Hanlon, Fekadu, Medhin and Teferra2019).

A recent review found over 400 measures of stigma in mental illness, majority of which were unvalidated in the contexts in which they were used (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Earnshaw, Taverna and Vogt2018). In the last two decades, new measures were developed at an approximate rate of 36 measures annually perhaps due to the nuances in the conceptualization of the construct of stigma (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Earnshaw, Taverna and Vogt2018). The rapid increase in the development and use of unvalidated measures of stigma may have saturated the need for new scales, and future studies should focus on validating and improving available measures. In this study, we validated the Mental Awareness Knowledge Schedule (MAKS) (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Little, Meltzer, Rose, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2010), Reported and Intended Behaviours Scale (RIBS) (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Rose, Little, Flach, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2011) and Community Attitudes Toward the Mentally Ill scale (CAMI) (Taylor and Dear, Reference Taylor and Dear1981) in a community sample in Kilifi Kenya. The MAKS, RIBS and CAMI assess knowledge, behavior and attitude, respectively. These tools have been validated in community samples from high-income settings and results suggest that the original one- and two-factor structures of the RIBS and MAKS, respectively, are valid in the assessment of stigma (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Golay, Favrod and Bonsack2017) but the original four-factor structure of the CAMI does not hold in community samples (Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Hall, Levings and Murphy1993; Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Pathare, Craig and Leff1996; Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Golay, Favrod and Bonsack2017). However, there are no data on the validity of these tools in the assessment of mental health stigma in Kenya.

The MAKS (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Little, Meltzer, Rose, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2010) is a 12-item questionnaire that measures a heterogenous group of items relating to mental health knowledge. It is divided into two parts that measure stigma-related mental health knowledge and knowledge about specific mental illness conditions. Previous validation studies reported poor internal consistency of the MAKS scale (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Little, Meltzer, Rose, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2010; Pingani et al., Reference Pingani, Sampogna, Evans-Lacko, Gozzi, Giallonardo, Luciano, Galeazzi and Fiorillo2019). However, because people's knowledge may be domain specific, internal consistency is not a relevant measure of this tool's utility. The RIBS scale (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Rose, Little, Flach, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2011) is an 8-item scale that measures the prevalence of observed behavior (items 1–4) and intended behavior (items 5–8). Previous studies have found good psychometric properties of the RIBS scale (Pingani et al., Reference Pingani, Evans-Lacko, Luciano, Del Vecchio, Ferrari, Sampogna, Croci, Del Fatto, Rigatelli and Fiorillo2016). CAMI (Taylor and Dear, Reference Taylor and Dear1981) is a 40-item scale designed to measure attitudes of the general population toward people with mental illness. It comprises four domains (each with 10 questions): authoritarianism, benevolence, social restrictiveness and community mental health ideology. Each domain has 10 questions each. Authoritarianism reflects the view that people with mental illness are inferior and that they should be handled using force or threats. Benevolence involves a sympathetic view of patients based on religious and humanistic principles. Social restrictiveness is a view that the mentally ill are a threat to society. Community mental health ideology is the idea that the whole community should work together through a variety of community resources to assist patients.

In low- and middle-income countries, these tools have been used for general populations (Abi Doumit et al., Reference Abi Doumit, Haddad, Sacre, Salameh, Akel, Obeid, Akiki, Mattar, Hilal, Hallit and Soufia2019), community samples (Girma et al., Reference Girma, Tesfaye, Froeschl, Moller-Leimkuhler, Muller and Dehning2013; Reta et al., Reference Reta, Tesfaye, Girma, Dehning and Adorjan2016; Basu et al., Reference Basu, Sau, Saha, Mondal, Ghoshal and Kundu2017; Hartini et al., Reference Hartini, Fardana, Ariana and Wardana2018; Abi Doumit et al., Reference Abi Doumit, Haddad, Sacre, Salameh, Akel, Obeid, Akiki, Mattar, Hilal, Hallit and Soufia2019; Niedzwiedz, Reference Niedzwiedz2019; Tesfaye et al., Reference Tesfaye, Agenagnew, Terefe Tucho, Anand, Birhanu, Ahmed, Getenet and Yitbarek2020; Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021) and special populations such as health professionals and medical students (Mutiso et al., Reference Mutiso, Musyimi, Nayak, Musau, Rebello, Nandoya, Tele, Pike and Ndetei2017; Siqueira et al., Reference Siqueira, Abelha, Lovisi, Sarucao and Yang2017; Fekih-Romdhane et al., Reference Fekih-Romdhane, Chebbi, Sassi and Cheour2021). However, they have also not been validated in most of these settings yet studies that have validated the tools in community samples show that while their original factor structures are retained in some samples (Abelha et al., Reference Abelha, Goncalves Siqueira, Legay, Yang, Valencia, Rodrigues Sarucao and Lovisi2015), they do not hold in others (Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Hall, Levings and Murphy1993; Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Pathare, Craig and Leff1996; Abelha et al., Reference Abelha, Goncalves Siqueira, Legay, Yang, Valencia, Rodrigues Sarucao and Lovisi2015). In Kenya, only one study has used all three tools to evaluate effectiveness of an anti-stigma social marketing campaign, but this study did not translate the tools to Kiswahili, which is Kenya's lingua franca, and it did not conduct any psychometric analysis to validate the tools for the population on which they were used (Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021).

This study validated and evaluated the psychometric properties of the Kiswahili versions of the CAMI, MAKS and RIBS scales, in a community sample in Kilifi Kenya. This analysis was part of a preliminary phase of a study that will provide contextually valid stigma tools for the measurement of the effectiveness of the Difu Simo Mental Health Awareness Campaign (Collaborators, 2019; https://difusimo.org), which will address mental health stigma in Kilifi county.

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted at the Kilifi County Hospital (KCH) which is the largest teaching and referral hospital in Kilifi. KCH is in Kilifi township, the administrative and commercial headquarters of Kilifi. Kilifi county is predominantly rural and is located along the coast of the Indian Ocean with a population of ~1.5 million residents (KNBS, 2019). The main economic activities are agriculture, fishing, tourism and small-scale trade. Kiswahili language is Kenya's lingua franca. The burden of common mental and neurological disorders in this population is high (Ngugi et al., Reference Ngugi, Bottomley, Scott, Mung'ala-Odera, Bauni, Sander, Kleinschmidt and Newton2013; Kariuki et al., Reference Kariuki, Abubakar, Kombe, Kazungu, Odhiambo, Stein and Newton2017; Kind et al., Reference Kind, Newton and Kariuki2017) and there is evidence of stigma toward people with these disorders in Kilifi (Mbuba et al., Reference Mbuba, Abubakar, Odermatt, Newton and Carter2012).

Participants

Between August 2020 and June 2021, a community sample of people ⩾18 years, living within a 25-km radius of KCH was recruited. Distance restriction was applied to minimize participant movement in adherence to the government's COVID-19 guidelines (MOH, 2020). The study was advertised through local government administrators and participant recruitment was sequential on a first-come first served basis until the desired sample size was achieved. Lack of fluency in Kiswahili language and severe mental or neurological disability and incapacity to consent or participate as verified by a clinician and patient's ability to provide informed consent were the exclusion criteria. Based on expected values of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) from existing literature (Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Hall, Levings and Murphy1993; Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Pathare, Craig and Leff1996; Pingani et al., Reference Pingani, Sampogna, Evans-Lacko, Gozzi, Giallonardo, Luciano, Galeazzi and Fiorillo2019; Tong et al., Reference Tong, Wang, Sun and Li2020) we aimed for a sample size >600. This sample size would be well powered for other analyses such as reliability testing which requires fewer samples (N = 100) to detect acceptable correlations (>0.3) with >0.80 accuracy.

In addition, we collected self-reported sociodemographic data on participants' experience with mental illness or epilepsy either as caregivers or patients. Qualitative research from the study setting indicates that epilepsy is viewed as a mental rather than neurological illness and patients are likely to face the same stigma as those with mental illnesses (Bitta et al., Reference Bitta, Kariuki, Omar, Nasoro, Njeri, Kiambu, Ongeri and Newton2020). Caregivers were defined as primary care providers for persons with either mental illness or epilepsy. Medical records were used to verify those who identified as patients. Face to face interviews were conducted by trained raters. After the first interview, participants were provided with additional information about the Difu Simo awareness campaign. They were given vignettes about common mental disorders, fliers and links to the project's website and social media pages.

Measures

English versions of the three scales were translated to the Kiswahili language and validated. Translation to Kiswahili followed the World Health Organization's guidelines of forward translation, expert panel back translation, pretesting, cognitive interviewing and testing of the final version (WHO, 2009). Forward translation from English to Kiswahili was done by two independent translators fluent in the Kiswahili language. Back translation of the Kiswahili tools was done by three clinicians. We then invited the first 20 participants who enrolled for the study to pretest the tools and provide feedback on tool wording. This feedback was then used to create the final version of the tools (online Supplementary files 1–3). Changes included revision of phrases to make contextual sense for instance question n of the CAMI scale ‘Increased spending on mental health services is a waste of tax dollars’ was revised to read ‘Increased spending on mental health services is a waste of tax money’ since Kenya's currency is shillings.

For all the three scales, items were originally coded on an ordinal scale of 1 to 5 where 1 represented strongly disagree and 5 represented strongly agree. Neutral responses were scored as 3. Summated scores were calculated by adding the points obtained for each question. Higher scores indicated higher levels of knowledge for the MAKS, favorable attitudes toward people with mental illness for the CAMI and favorable intended behaviors for the RIBS. For the MAKS, items 6, 8 and 12 were reverse coded to ensure consistency with direction of the right responses for other questions.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using STATA (Version 15). Two-way analysis of variance or Mann–Whitney U test were used where appropriate to compare: (i) the distribution of sociodemographic characteristics between males and females and across the different groupings of experience with mental illness or epilepsy and (ii) to compare the composite scores between groups. All items were treated as continuous variables.

Validity

To evaluate the internal validity of all the scales we first conducted CFA to validate (i) original structure as proposed by the tool developers and (ii) alternative structures available in literature from community samples (Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Hall, Levings and Murphy1993; Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Pathare, Craig and Leff1996). Where the original structure and structures suggested in literature could not be established, we investigated alternative structures by conducting exploratory factor analysis (EFA) where the sample was randomly split into two equal sizes and then EFA was conducted using principal factor analysis with Promax rotation. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity were used to determine the factorability of the scales. A KMO value of <0.5 value was acceptable. To determine the number of factors to extract, we first conducted principal factor analysis and then used the STATA command ‘fapara’ to conduct parallel analysis. Parallel analysis was conducted to determine the number of factors to extract. Additionally, the following criteria were applied to extract the factors (Norris and Lecavalier, Reference Norris and Lecavalier2010): (i) each factor contained only items that explained ⩾10% of the factor's variance, (ii) factors had at least three items loading with a factor loading ⩾0.32, (iii) only items that did not cross load on multiple factors with similar magnitudes were extracted and (iv) factors were interpretable in a contextually sensible way.

We then used CFA to validate the alternative structure using structural equation modeling to produce standardized factor loadings and goodness of fit measures, specifically the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean-squared error of approximation (RMSEA). An RMSEA ⩽ 0.06 and CFI and TLI ⩾ 0.95 were interpreted as good fits with RMSEA ⩽ 0.08 and CFI/TLI ⩾ 0.90 considered acceptable (Hu and Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). We analyzed a polychoric correlation matrix and used diagonally weighted least squares to estimate model parameters.

To measure convergent validity, we used Pearson's correlation coefficient to test the hypothesis, from previous studies that the summated MAKS scale scores were positively related to both the summated RIBS and CAMI scores (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Golay, Favrod and Bonsack2017).

Reliability

We used the Stata command ‘kappaetc’ to calculate inter-rater reliability. This command produces the following coefficients: percent agreement, Brennan and Prediger's coefficient, Cohen's kappa (κ), Scott/Fleiss' kappa, Gwet's AC and Krippendorff's alpha. For all the coefficients, a score of 1 suggested perfect agreement while a score closer to 0 suggested poor agreement between two independent interviewers. Inter-rater interviews were conducted approximately 1 h apart. Using the intra-class correlation coefficients, we measured test–retest reliability by comparing the reliability of means approximately 2 weeks apart. We used the McDonald's omega (ωt) to measure the internal consistency of all the scales because it performed better in a Monte Carlo simulation even when the item distributions were skewed (Trizano-Hermosilla and Alvarado, Reference Trizano-Hermosilla and Alvarado2016).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

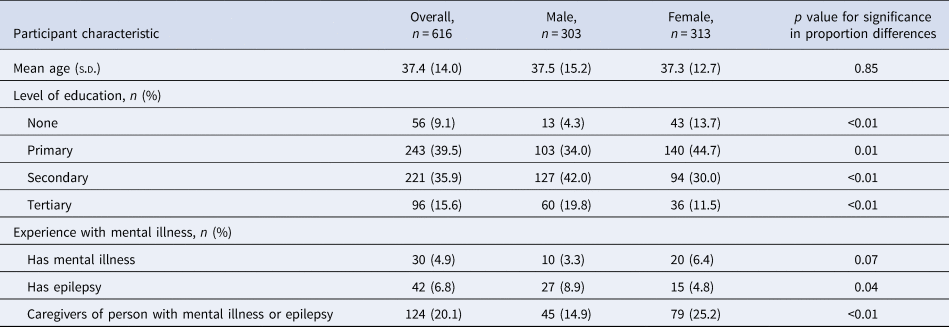

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. In total, we recruited 624 participants, but eight participants had incomplete data in at least one of the tools and were excluded from analysis. Therefore, our final sample size was 616 participants, of whom 313 (50.8%) were female. Participants' mean age was 37.4 (s.d. = 14) with no significant differences between men and women (p = 0.85) and the age range was 18–92 years. In total, 196 (31.8%) participants had lived experience with mental illness or epilepsy, either as patients (n = 72, 11.7%) or caregivers (n = 124, 20.1%). There were significantly more male patients with epilepsy (p = 0.03), while caregivers of people with epilepsy or mental illness were predominantly female (p < 0.01). Females had higher proportions of participants with no formal education (p < 0.01), while there were more male participants with secondary (p < 0.01) and tertiary education (p < 0.01).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

Distribution of item responses

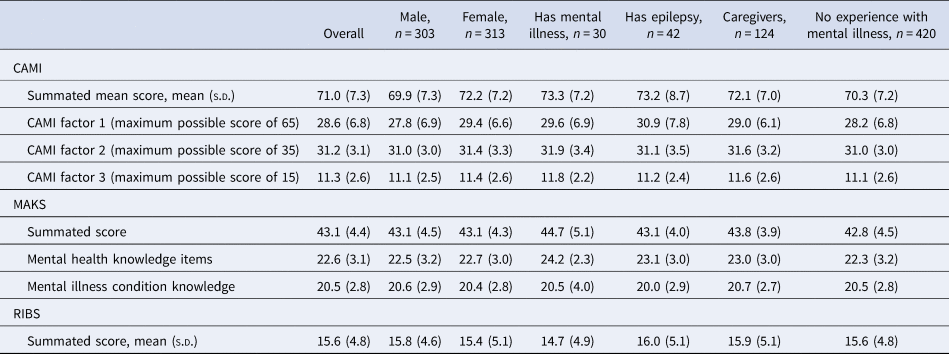

Results for all summated scores are provided in Table 2. The summated mean score of the RIBS scale was 15.6 (s.d. = 4.8) out of a possible 20 and there was no difference (p = 0.76) in the summated mean scores between those with mental illness (15.6, s.d. = 4.7) experiences and those without (15.7, s.d. = 5.0). There were no significant differences in the distribution of scores by sex or experience with mental illness but there was a significant difference by levels of education (p = 0.00) as shown in online Supplementary Table S1. Over 50% of the respondents selected the response ‘strongly agree’ in questions 5, 7 and 8 of the RIBS scales. For question 6 ‘In future, I would be willing to work with someone with a mental health problem’, 45.1% of the respondents selected the ‘strongly agree’ response as shown in online Supplementary Table S2.

Table 2. Summated and subscale mean scores and standard deviations of the original CAMI, MAKS and RIBS scales by sex and experience with mental illness

The mean MAKS score was 43.1 (s.d. = 4.4) out of a possible 60 and those with experience in mental illness had significantly higher levels of knowledge than those without (42.8, s.d. = 4.5 v. 43.8, s.d. = 4.1, p = 0.01). Sixty five percent of respondents strongly disagreed with item 6 ‘Most people with mental health problems go to a healthcare professional to get help’. Schizophrenia was recognized as a mental disorder by 83.4% of the participants, followed by drug addiction (57.5%), then depression and bipolar disorder (49.2% each) as summarized in online Supplementary Table S3. There was no significant between group difference by sex (p = 0.99) but there were significant differences by level of education (p = 0.02) and experience with mental illness (p = 0.01) (online Supplementary Table S1).

The mean CAMI score was 71 (s.d. = 7.3). People with mental illness experiences had significantly better attitudes than those without (196: 72.6, s.d. = 7.4, v. 70.3, s.d. = 7.2, p < 0.01). Results of the frequency distributions for each of the 40 CAMI items are shown in online Supplementary Table S4. Women had significantly higher scores in factor one scores (p = 0.00) compared to men. Additionally, level of education had a significant association with overall scores for factor one (p = 0.00) but not factor two (0.65) or three (0.60) as indicated in online Supplementary Table S1.

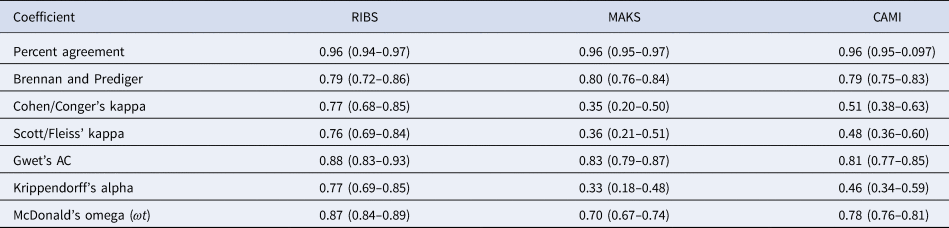

Reliability

As summarized in Table 3 RIBS [ωt = 0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84–0.89] had a good internal consistency while CAMI (ωt = 0.78, 95% CI 0.76–0.81) and MAKS (ωt = 0.70, 95% CI 0.67–0.74) had acceptable internal consistencies.

Table 3. Reliability of the stigma scales with 95% CIs

Inter-rater reliability testing was conducted on 161 (26.1%) participants. Data on percentage agreement and coefficient scores are presented in Table 3. Percentage agreement was high (>96%) for all the scales while kappa coefficients ranged from 0.4 (95% CI 0.2–0.5) using Cohen's kappa to 0.9 (95% CI 0.8–0.9) using Gwet's coefficient. Test–retest reliability was assessed for 59 participants (9.6%). It was excellent for RIBS (Intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0.81, 95% CI 0.71–0.88) and poor for CAMI (ICC = 0.39, 95% CI 0.05–0.60) and MAKS (ICC = 0.19, 95% CI −0.26 to 0.47).

Validity of the stigma scales

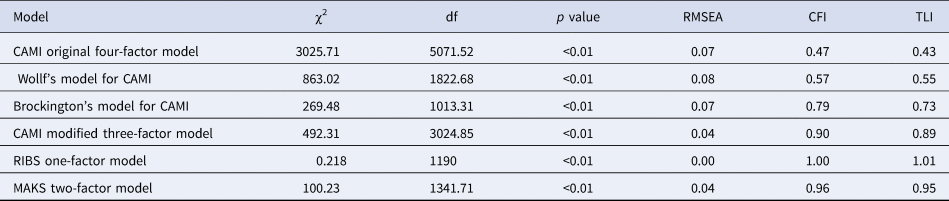

The original one- and two-factor structure for the RIBS (RMSEA < 0.01, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.01) and MAKS (RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95), respectively, were established for this sample. The original four-factor structure for the CAMI could not be established (Table 4). We found two studies that validated the CAMI using community samples (Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Hall, Levings and Murphy1993; Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Pathare, Craig and Leff1996). Both studies proposed a three-factor structure, but these structures could not be established in our sample. We therefore conducted EFA to establish an alternative factor structure (online Supplementary Table S5). The KMO was acceptable (0.83) and the determinant of correlation matrix was significant (p < 0.01) indicating acceptable levels of correlation between items. Results of the parallel analysis proposed a six-factor structure, however three of the factors did not meet all our criteria, and we therefore retained three factors and a total of 23 questions. These factors cumulatively explained 86.1% of the variance. Online Supplementary Table S1 shows the factor loadings for each of the original 40 items. Factor one's items corresponded with the pro-authoritarianism, pro-social restrictiveness and anti-community mental health initiative domains of the original four-factor structure. Factor two corresponded with pro-benevolence, anti-authoritarianism and pro-community mental health initiative domains. Factor three corresponded with anti-social restrictiveness, anti-authoritarianism and pro-community mental health initiative domains.

Table 4. Comparisons of model fits for the three stigma scales, n = 616

Acceptable indices of goodness of fit were <0.06 for RMSEA and >0.90 for CFI and TLI.

χ2, chi-squared; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; df, degrees of freedom; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index.

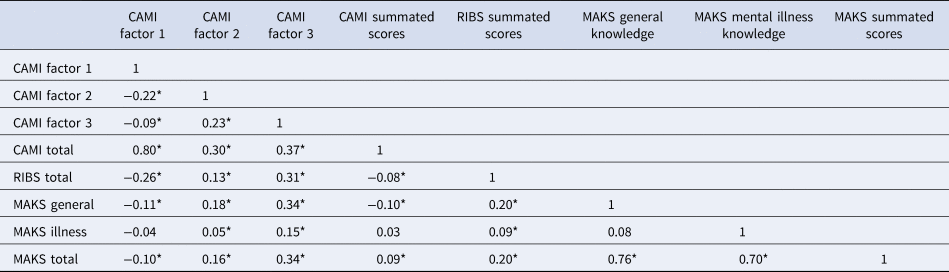

Summated MAKS score was positively related to both the summated RIBS (coefficient = 0.2, p < 0.05) and CAMI scores (coefficient = 0.09, p < 0.05). Each of the CAMI factors were also correlated with the MAKS summated scores and RIBS summated scores as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Convergent validity of the three stigma scales

*p < 0.05.

Discussion

This study validated and evaluated the psychometric properties of the CAMI, RIBS and MAKS scales in a community sample in Kilifi Kenya. The indices for goodness of fit for the original RIBS and MAKS scales were excellent, so are applicable in our settings. Internal consistency was good for RIBS, acceptable for CAMI and low for MAKS, indicating that items are less related in the former scale and should be evaluated in future studies. The original one- and two-factor structures for the RIBS and MAKS, respectively, were retained in this sample, underscoring cross-cultural invariance of the scale. CAMI fitted into a three-factor structure that comprised of 23 out of the original 40 questions, suggesting that a shorter version may better fit this population, where literacy levels are low. The three scales likely measure a common construct of stigma since MAKS showed good convergent validity with both the RIBS and CAMI scales. These findings together suggest that the Kiswahili versions of the original RIBS and MAKS scales can be used to measure stigma in Kilifi.

Our sampling technique was not entirely random since we used a community sample that lived around KCH, and the population around this area is relatively urban compared to the rest of the county. The study population is part of a health and demographic surveillance system (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Bauni, Moisi, Ojal, Gatakaa, Nyundo, Molyneux, Kombe, Tsofa, Marsh, Peshu and Williams2012) where anti-stigma interventions have been conducted over the years (Ibinda et al., Reference Ibinda, Mbuba, Kariuki, Chengo, Ngugi, Odhiambo, Lowe, Fegan, Carter and Newton2014; Collaborators, 2019) and this may have contributed to the higher levels of knowledge. Indeed, compared to other studies (Pingani et al., Reference Pingani, Evans-Lacko, Luciano, Del Vecchio, Ferrari, Sampogna, Croci, Del Fatto, Rigatelli and Fiorillo2016; Pingani et al., Reference Pingani, Sampogna, Evans-Lacko, Gozzi, Giallonardo, Luciano, Galeazzi and Fiorillo2019) item responses were skewed toward higher scores meaning that participants reported higher levels of knowledge, better attitudes and better intended behaviors. Additionally, participant recruitment, like in any survey, relied on cooperative participants who were likely to have more tolerant attitudes. Acquaintance to mental illness by patients or caregivers contributes to willingness to participate in mental health research (Crisp and Griffiths, Reference Crisp and Griffiths2014) and higher levels of tolerance toward the mentally ill (Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Hall, Levings and Murphy1993). This may explain the overall high scores in our study in which 31% of the participants had experiences with mental illness.

Convergent validity measures showed that there was significant positive correlation between the summated MAKS and both the summated CAMI III and RIBS scores which is similar to a French study that examined the correlation between the RIBS and MAKS instruments (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Golay, Favrod and Bonsack2017). This indicates that the measures are theoretically related, which provides a rationale for using them together to measure the construct of stigma. However, we did not examine overlap between components of the different sub-scales and well-powered future studies should examine this to create a concise measure of stigma that taps on unique properties from each of the sub-scales. Internal consistencies of the CAMI and RIBS scales were acceptable, suggesting that their items were related to each other and were indeed measuring the stigma construct they intended to measure. The MAKS had a low internal consistency, which was comparable to that of the original sample on which the tool was developed. However, as explained by the tool developers, MAKS was not intended to function as a scale and the reliability values should only be used to explain trends in responses (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Little, Meltzer, Rose, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2010).

Although percent agreement between raters was high for all the scales, the kappa coefficients were acceptable for the RIBS, but low for the MAKS and CAMI scales. This phenomenon, referred to as the first kappa paradox (Feinstein and Cicchetti, Reference Feinstein and Cicchetti1990) was not surprising, since we expected that there would be a skewed distribution of the frequencies of responses because this population has been exposed to anti-stigma interventions (Collaborators, 2019). This finding should not be interpreted as a limitation but rather as a logical consequence of the model's attempt to correctly interpret agreement, adjusted for chance. The test–retest reliabilities for the CAMI and MAKS scores were poor, similar to findings of the original scales (Taylor and Dear, Reference Taylor and Dear1981; Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Little, Meltzer, Rose, Rhydderch, Henderson and Thornicroft2010) and of other validation studies (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Golay, Favrod and Bonsack2017). After the original data collection, participants were exposed to anti-stigma activities (Collaborators, 2019) which may have affected the retest responses. Given the acceptable internal consistencies of all the scales, the test–retest finding suggests that attitudes and knowledge are not enduring traits in this population. Similar findings have been observed in other parts of Kenya where there were no ongoing anti-stigma interventions (Potts and Henderson, Reference Potts and Henderson2021); taken together these findings suggest that sustained awareness campaigns may be useful in this setting.

In the CFA, we found that a modified three-factor model, two-factor model and one-factor model for the CAMI, MAKS and RIBS scales, respectively, should be favored for the Kiswahili versions. The two- and one-factor model solutions for the MAKS and RIBS scales are similar to those of French and Portuguese validation studies (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Golay, Favrod and Bonsack2017; Silva Ribeiro et al., Reference Silva Ribeiro, Gronholm, Silvestre De Paula, Scopel Hoffmann, Olider Rojas Vistorte, Zugman, Pan, Mari, Rohde, Miguel, Bressan, Salum and Evans-Lacko2021), underscoring configural invariance of these scales. Compared to our study, the French study had better indices of goodness of fit for the MAKS scale probably because it was conducted among nursing students, whose understanding of mental health is much better compared to our community sample. RIBS- and MAKS-factor structures corresponded perfectly with the original scales of a one- and two-factor structure, respectively, suggesting that the translated Kiswahili versions of the original scales can be used for this population.

CAMI's modified three-factor model with 23 items performed best, and it is possible this shorter version works better in this population because of low literacy levels. Although our items did not perfectly correspond with those of Brockington (Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Hall, Levings and Murphy1993) and Wolff (Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Pathare, Craig and Leff1996) who validated this tool in community samples, our three-factor structure suggested three levels of tolerance similar to their studies. First, an authoritarian attitude that reinforces isolation of people with mental illness, second a tolerant attitude and lastly a sympathetic attitude toward those with mental illness. This finding is perhaps timely as it may inform implementation of Kenya's 2021–2025 Mental Health Action plan, that includes among other things, plans to increase mental health literacy and reduce stigma (HealthTaskforce, 2021).

We found significant associations between some sociodemographic variables and stigma scores, using simple tests of comparison which suggested that further multivariable analysis is required to determine the sociodemographic correlates of stigma scores. These analyses will be conducted and presented as a separated manuscript, as part of a quantitative evaluation of the Difu Simo campaign.

Strengths and limitations

The study had some strengths. First, persons with experience in mental illness or epilepsy were included, which allowed for comparison of stigma measures among those with and without mental health experiences. Second, the relatively large sample size allowed for robust validation models. Lastly, inclusion of all three tools allowed for measures of convergence among the three constructs of stigma, providing insights into their relationships in this setting. Our study combined EFA and CFA, a practise that is encouraged when the aim of a study is to identify latent structures that can be generalized and are clinically useful (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Sass, Chappelle and Thompson2018). Simulation studies have found that use of single-factor analytic approaches create challenges such as models overfitting data and producing errors and noise resulting in factors that are not clearly interpretable and hence cannot inform theory development (Montoya and Edwards, Reference Montoya and Edwards2021; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Watts, Forbes, Kotov, Krueger and Eaton2022).

This study also has limitations. We did not validate the short version of the CAMI scale independently. We only administered the questionnaire in its long form and hence we could not calculate the correlation between the long form and the short form because as described by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Mccarthy and Anderson2000) this method would lead to an overestimation of the correlation between the two forms. Additionally, factors such as sample characteristics, linguistic adaptation and data-driven decisions in the analysis and interpretation may have contributed to the poor fit of the full version of the CAMI scale. Therefore, we recommend that authors should use the full 40-item versions as a start and conduct validation studies in their study populations. For Kilifi, where this study was conducted, future validation steps will include subjecting the excluded 17 questions to cognitive debriefing and cultural equivalence to assess the clarity of instructions and the comprehensibility of the content. Additional steps will include content equivalence exercises which will involve expert evaluation of relevance of contents (Sousa and Rojjanasrirat, Reference Sousa and Rojjanasrirat2011 #3).

Our study did not systematically examine essential unidimensionality of each scale, that is whether the set of items measured only one attribute or dimension. We recommend that future studies examine this assumption to improve interpretability overall scores, such as those used in our construct validity models. Lastly, we cannot quantify the extent to which social desirability influenced the results.

Conclusions

The Kiswahili version of the original MAKS and RIBS scales can be used to assess knowledge and behavior in Kilifi. CAMI-23 scale may be best suited for this population, but further studies are required to validate it against other scales measuring similar construct of knowledge. Despite earlier anti-stigma interventions of epilepsy in the area, problem of stigma is still substantial in this area. The constructs of stigma are not enduring traits in this population suggesting that anti-stigma interventions have a place in this setting.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.26.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Martha Kombe, Alfred Ngombo and Hamisi Rashid for translating and backtranslation the tools. We thank Patrick Mwaro, James Kahindi, Prudence Kalama, Yvonne Thoya and Evelyne Mwarumba for collecting the data used in this study.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust grant number 213763/Z/18/Z. The funders did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study or the interpretation of study findings.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the Scientific and Ethics Review Unit of the Kenya Medical Research Institute under protocol number KEMRI/SERU/CGMR-C/167/3933. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.