When Ekrem İmamoğlu won as Istanbul’s mayor in spring 2019, it was viewed as a significant breakthrough in challenging Turkey’s illiberal populist regime. As seen in Hungary, Poland, and even other Turkish cities, mayors try to use their city as springboards for effectively challenging illiberal, competitive authoritarian regimes and deepening democracy. However, despite the recent increase in cases and the importance of the issue for understanding how to increase liberal democratic space in these polarized states, the dynamics of contention between mayors and the central government remains under-studied in political science. The primary contribution of this article is to set out a model of these dynamics that can be usefully deployed across cases. The model starts with an understanding of the regime as a dense vertical network that is bounded by an identifiable national and/or religious identity, colludes with business and taps into international financial flows to fund clientelism, and uses media dominance to promote certain nationalist narratives and delegitimize opponents. To expand space for pluralist democracy, opposition mayors target key elements of this network. They seek to reinvigorate a sense of effective democratic citizenship by increasing access to information, creating denser and more inclusive local governance networks, limiting the ruling party’s opportunities for rent-seeking, and (re)creating a sense of social solidarity across identity groups. The central government in turn aims to thwart the mayor’s progress on these fours tasks. After further developing the model, the article uses the case of Istanbul to illustrate it.

Having a clear method for comparing opposition cities under illiberal regimes would be an important step in moving forward research on these cities. The current literature on opposition victories in competitive authoritarian regimes usually focuses on the national level and tends to be pessimistic on the prospects for real change (Bunce and Wolcik 2002; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002; and Hale Reference Hale2014). For an exception, Lucardi’s (Reference Lucardi2016) study of Mexican cities does address how cities can be agents for democratization through access to resources and demonstration effects. However, as a large-N study looking at the geography of opposition wins over time, there is a little attention to urban governance or city-state relations. On the other side, cities are key to maintaining illiberal populist regimes. While illiberal populism is often viewed as a reaction to the alienation of neoliberal governance and liberal cultural hegemony (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2022), citizen encounters with neoliberalism often take place at the city level, so cities engage in nationalism and populism to manage local discontent (Koch and Valiyev Reference Koch and Valiyev2015; Deets Reference Deets2022). This reality both fuels identity-based clientelism and creates opportunities for the opposition to argue for a new kind of politics.

To illustrate the strategies used to attempt to shift the network in Istanbul from 2019 through 2022, this article draws on 14 unstructured interviews (several with multiple individuals) conducted in Istanbul in Spring 2022 and subsequently online. The interviews encompass government officials at different levels and in very different parts of the city government (city administration, city council, city-owned subsidiaries, and a district government), three civil society organizations with very different foci (urban activism, voting rights, and business interests), and Republican (CHP), IYI, and People’s Democracy Party (HDP) officials and activists. As the goal was to better understand how the city government currently functions and relates to the central government and the city’s citizens, the interviews targeted individuals who currently work for or with the city administration, and the narratives of the city administration’s approach to governance was remarkably similar across interviews and consistent with media reports. The similarities in the interviews include reports about efforts to increase civic engagement, increase commitments to transparent processes, and play down ethnic and religious differences to tout how İmamoğlu was the mayor for everyone.

The next section lays out how illiberal populism addresses challenges of democracy under neoliberalism through the creation of a tight vertical network. The interrelated four core strategies of the opposition (increasing information, broadening the actors in governance networks, increasing social solidarity, and limiting rent-seeking and clientelism) emerge from this discussion. This will be followed by an overview of how Erdoğan used financial flows and ethno-sectarian rhetoric to create a powerful vertical network. After an overview of the 2019 campaign, the article details the governance by the opposition in Istanbul and the counter-strategies by the central government. The conclusion summarizes the city’s progress on these efforts, and, pointing toward future research, offers some initial thoughts on factors that have facilitated this progress.

How Populism Resolves Democratic Challenges under Neoliberalism

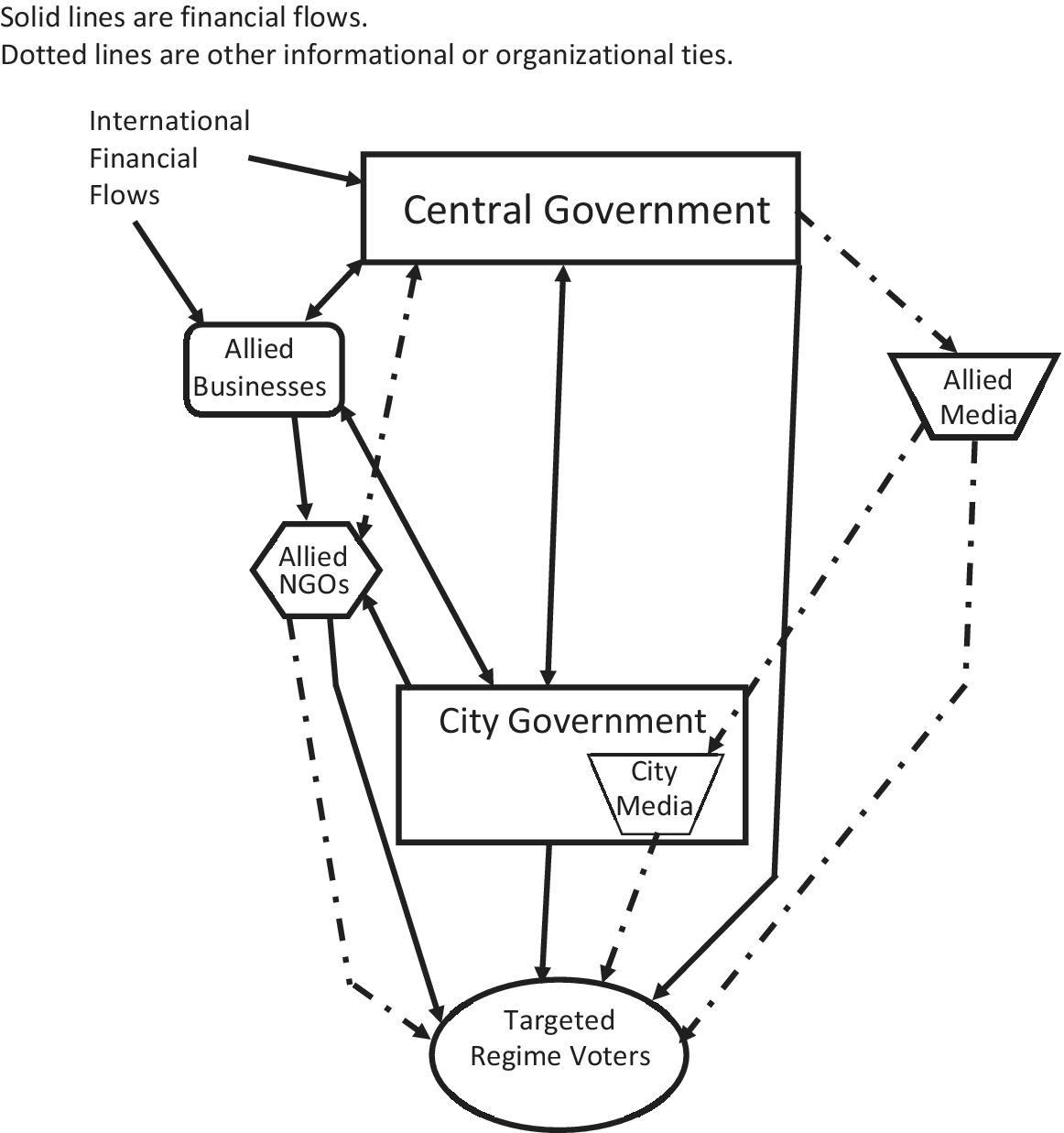

The terminology describing hybrid democratic regimes has proliferated, including illiberal or ethno-populism, competitive authoritarianism, and authoritarian neoliberalism. This article accepts Mudde’s (Reference Mudde2004) idea of populism as a thin ideology that incorporates nativism, authoritarianism, and anti-establishment sentiment. Illiberalism emphasizes the rejection of individual rights, which are associated with the secular, immoral degradation of the West, in favor of collective traditional values rooted in majoritarianism (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2022). Ethno-populism is similar, although it draws attention to the defended traditional values being rooted in the nation (Jenne Reference Jenne2018); it is for this reason that Stroschein (Reference Stroschein2019) notes that researchers of nationalist parties and right-wing populist parties are looking at similar cases despite the difference in terminology. Competitive authoritarianism serves as a reminder that even while problematic, elections in these countries matter (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002). Erdoğan, for example, has emphasized the legitimating power of elections and how they are expressions of the popular will (Demiralp and Balta Reference Demiralp and Balta2021). Authoritarian neoliberalism evokes the idea that this may be a late (or latest) stage of neoliberalism (Arsel Reference Arsel, Adaman and Saad-Filho2021). These states heavily rely on real estate development and global finance despite associated problems; in fact, the authoritarian elements are necessary because of public opposition to growing inequality and land-use changes. But this raises the core contradiction inherent in these regimes – the nativism and anti-elite sentiments are in service of enriching business elites who have access to both the government and global markets. All three frames are quite apparent in Turkey in general and Istanbul in particular, but the term “illiberal populism” is used here as it captures both the role of religious and nationalist values in the boundary creation between regime supporters and opponents and the populist network structure of how these regimes manage neoliberalism (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Vertical Network in an Illiberal Populist Regime when the same party controls the central and city governments.

As long as elections are not merely performative, questions emerge on how to defeat powerful populists and the role of local politics in this. A broad coalition crossing important ideological and identity divides has been shown a necessary but insufficient condition. At the local level, the key question is not just how the opposition wins the mayoral races, but what happens next. The win itself can create optimism that the regime is beatable (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002; Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2010). As suggested by Lucardi (Reference Lucardi2016), local governments can marshal resources, build experience that candidates can run on in the future, enact alternative policies, and demonstrate new modes of governance. But there is no guarantee that the opposition continues to win as the regime fights back.

The dynamics of contention between the opposition and government reflects the nature of illiberal populist regimes. This model starts with an understanding of liberal democracy as a network of horizontal ties involving individuals, politicians, civil society, and political institutions, which produces social trust and effective governance (Putnam et al. Reference Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti1994; Ádám Reference Ádám2020). For this to happen, there must be strong and responsive institutions, and civil society must be an arena of cross-cutting and not reinforcing cleavages. Otherwise, civil society can overwhelm the state, contribute to polarization, and/or be incorporated into populist, authoritarian movements (Berman Reference Berman1997; Gellner Reference Gellner1994).

Work on network governance looks at these issues from inside the state. In providing social services, formulating and enforcing regulations, and performing other public duties, modern states are not hierarchical Weberian institutions. Instead, agencies, bureaucrats, and politicians are enmeshed in networks with private sector actors, non-governmental organizations, and others specialized interests. While some ties may be direct, often the system depends on brokers who connect actors and help regulate information and resources. Actors inside the state must weigh the trade-offs of relying on a small number of closely tied actors, which is associated with high levels of trust and efficiency, or the greater information and creativity of heterogeneous groups in the network (Ahuja Reference Ahuja2000). Issues of accountability, responsiveness, inclusiveness, and effectiveness are therefore endemic to modern governance (Provan and Kenis Reference Provan and Kenis2008; Provan and Milward Reference Provan and Milward2001).

When networked governance functions well, it increases communication, learning, and collective capacity. The collective relational identity that brings the network into being is also reinforced through the network (Ibarra, Kilduff, and Tsai Reference Ibarra, Kilduff and Tsai2005; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2013). In a liberal democracy, in theory, feelings of responsible citizenship bring these inter-connected networks together. But these feelings of effective citizenship only accrue to those actively participating in the networks. Contemporary democracy, a system in which individuals believe they have a right to feel valued politically, has a Herculean task in creating and maintaining feelings of effective citizenship as the costs are so high (Ádám Reference Ádám2020). There is an overload of information and issues, making it nearly impossible for voters to feel competence over issues impacting them and their community. Voting is an imprecise mechanism for communicating interests, leaving politicians unclear about public policy preferences and challenging voters’ ability to hold politicians accountable. It is therefore difficult for voters to feel heard, like they matter. Still, democracy can remain vibrant if there is easy access to clear and reliable information, if strong government institutions are responsive within inclusive networks, and if cultural norms encourage social solidarity. Neoliberalism presents a serious challenge as it so often alienates individuals from civil society, disrupts horizontal governance networks, creates greater economic inequality, challenges cultural norms, and decreases state capacity. The result is a large pool of citizens that for both cultural and economic reasons feel alienated and lack attachment to the prevailing social order and the mainstream parties and civil society organizations that represent it (Berman and Snegovaya Reference Berman and Snegovaya2019; Stroschein Reference Stroschein2019; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2020). At the same time, governance networks have become dominated by a small number of groups that have power either because of financial resources or specialized knowledge.

Illiberal populists address these challenges by building vertical linkages and internalizing costs for effective participation (Ádám Reference Ádám2020) (see Figure 1). This vertical network consists of overlapping systems of resource flows (solid lines) and narrative/information flows to reinforce a collective identity based on specific narratives (dotted lines). For those feeling alienated, they use direct communication and allied media to reassure these voters they are the “real” people, echo traditional cultural norms, create personalistic ties that makes them feel heard and valued, provide clear and compelling narratives around policy issues, and establish special economic benefits. In addition, new organizations serve as key brokers, building ties among like-minded citizens and connecting them to the party and leader. In these ways, the connection between voting and interest satisfaction seems transparent, and feelings of effective citizenship and community increase. Illiberal populists gain not only political power but financial as they engage in considerable rent-seeking (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2020). The government taps into international finance flowing into and through the country. Businesses, especially those tied to global capital markets, ally with the state because they can reduce risks from market volatility and gain stable earnings through preferential government contracts. The government uses this money to provide financial benefits to its voters and allied NGOs; in some cases, the financial benefits to voters come through the allied NGOs. To keep the system in place, the regime increases ethno-sectarian polarization, continues to undermine horizontal political ties and civil society, and increases the costs of information. Local governments allied with the center are used as conduits of, and reinforcements for, both financial and narrative flows. The goal is a bounded identity community with a dense internal network circulating resources and reinforcing collective identity.

If the opposition wins a country’s major city and wants to use it as a springboard for further change, they have to address the costs of democratic participation and resulting alienation while at the same time targeting the conditions allowing the regime to survive. They could mirror the illiberal populists by mobilizing their own voters, maintaining polarization, and creating their own vertical ties. This is often not achievable as the opposition is generally a broad coalition with its own capacity problems and likely faces strong headwinds from the central government. This “reciprocal polarization” is also a risky strategy as it does not seek to strengthen democratic foundations and continues to make elections extremely high stake (Somer et al. Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2021).

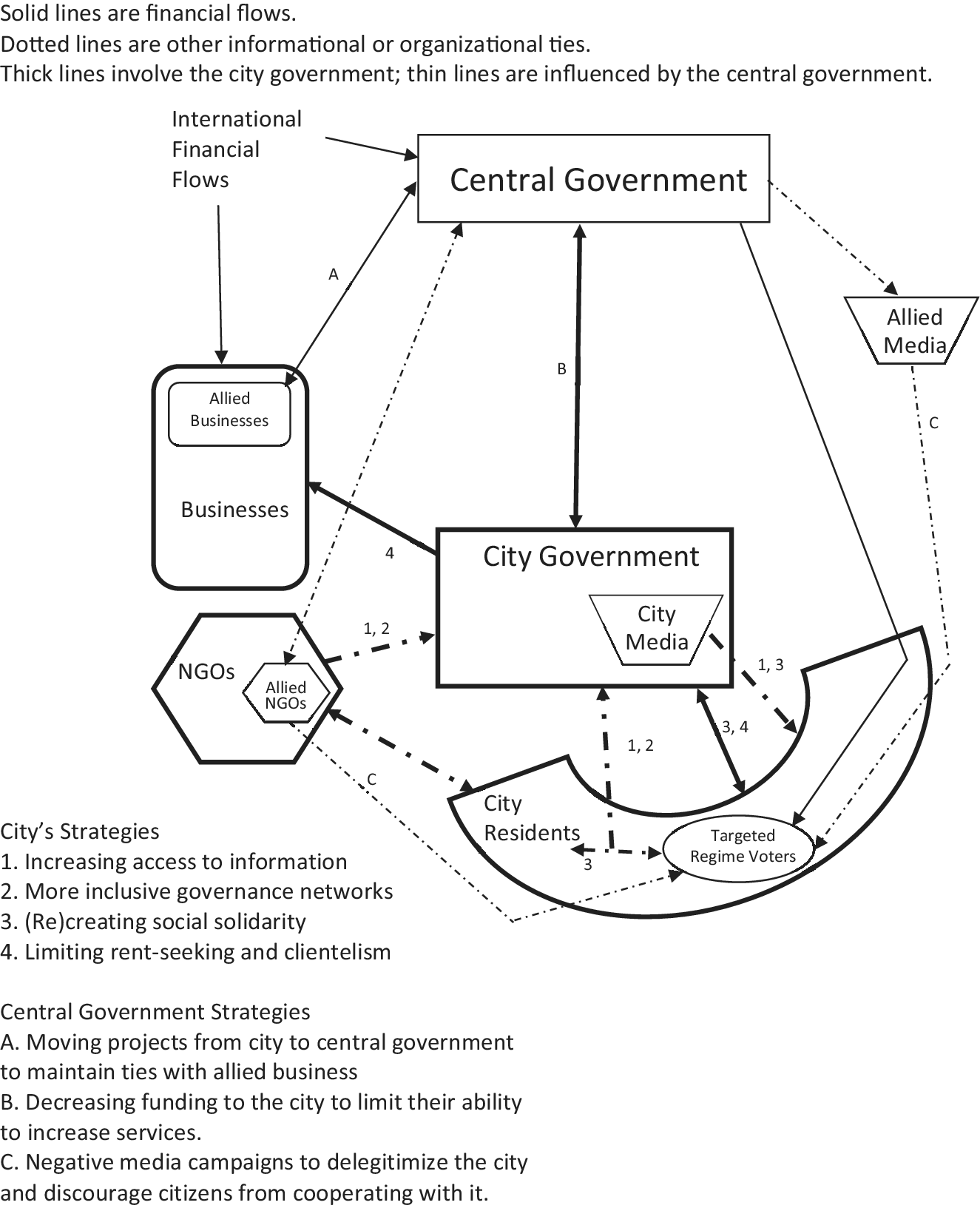

The second option is to try to address the conditions prompted by neoliberalism that have allowed the illiberal populist regime to emerge and stay in power. Seeking to re-empower citizens as citizens and re-build government capacity means trying to make the governance network less vertical and more horizontal (see Figure 2). The local government must increase transparency and access to information to increase civic competence and encourage public participation as well as confront anti-opposition government narratives; these strategies are primarily addressed through ties labeled 1 on Figure 2. Second, governance networks need to be consciously made more inclusive by building ties to a broad array of NGOs and creating clear paths for public participation; these strategies are primarily addressed through ties labeled 2 on Figure 2. The local governments also needs to proactively depolarize the city by (re)creating social solidarity on shared cultural norms and interests; these strategies are primarily addressed through ties labeled 3 on Figure 2. Some passive depolarization may occur through narratives of city initiatives benefiting all and increases in public participation, but effective depolarization requires deliberate action (Somer et al Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2021). Finally, the local government needs to disrupt the central government’s vertical network of resource flows. This may involve clawing back contracts, investigating corruption, opening contracts to more bidders, and increasing services to city residents as city residents; these strategies are primarily addressed through ties labeled 4 on Figure 2. As these strategies seek to increase pluralism, it very different than trying to supplant the regime with a new patron (Hale Reference Hale2014).

Figure 2. City’s goal for a more Horizontal Network in an Illiberal Populist Regime when an opposition party wins the city elections.

These four tasks may be more easily accomplished at the city than the national level. Urban identity is different from national identity. Even when neighborhoods are segregated, one recognizes the city’s diversity. Residents share common experiences of transportation, parks, markets, and much else in their daily lives that is under the city’s jurisdiction. As cities have their own competencies and deal with different issues than the national government, local politics may not be “political” in the same way. Still, cities are embedded in state structures, which means the state has some capacity to maintain its existing vertical network. Furthermore, the state can intervene to block expanding horizontal ties in the city, disrupt information flows, and maintain polarization. The central government’s primary strategies involve cutting city funding, promoting scandals, and moving lucrative contracting to bodies still under its control. These strategies are primarily addressed through ties labeled A, B, and C on Figure 2. How well the opposition opens democratic space depends on the extent of their progress in making the local governance more horizontal and disrupting the state’s vertical network in the face of the central government’s efforts to counter these strategies. While what happens in one part of the network has impacts on other parts of the network, we should not expect uniform progress in each area. The next section describes how Erdoğan constructed the current vertical network. Following this, the case of Istanbul is used to illustrate the strategies and mechanisms in Figure 2.

The Rise of Illiberal Populism in Turkey

The reverence for Kemal Atatürk, modern Turkey’s founder, historically challenged those who disagreed with his vision of a secular Turkey with a powerful state. This vision, long backed by a military that would interrupt democracy or support de facto one-party rule, kept in check the deep divisions between seculars and the religious, Sunni and Alevis, Turks and Kurds, etc. (Akkoyunlu and Öktem Reference Akkoyunlu and Öktem2016). This state-centric vision prompted import-substitution industrialization through the 1950s and 60s, in turn causing significant rural to urban migration. In Istanbul, the result was that over half the city became “informal settlements” in which people created housing on public land (Demiralp Reference Demiralp2018; NGO Activist 2022). After the 1980 military coup, the government launched economic reforms to shrink the state sector and open up to international finance, policies which expanded after the return to democracy in 1983. These reforms spurred economic dynamism in more religious central Turkey (Yabanci Reference Yabanci2016; Özden et al. Reference Özden, Akça, Bekmen and Tansel2017). Bringing conservative Muslims into the neo-liberal project had important long-term political implications (Erensü and Madra Reference Erensü, Madra and Tezcür2020). In 1990, this growing community of religious business owners formed the Independent Industrialist and Businessmen Association (MUSIAD) instead of joining the existing Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD). While both have broadly supported Turkey’s neo-liberal turn, TUSIAD is much larger, and its members tend to be better connected to global markets whereas MUSAID members are more likely to be small- and medium-enterprises with trade focused in the Middle East (Tanyilmaz Reference Tanyılmaz, Balkan, Balkan and Öncü2015; Entrepreneur 2022).

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan entered politics as a member of the Welfare Party, which had an Islamist orientation and vague economic policies, promoted traditional values, and opposed membership in the European Union. Winning as mayor of Istanbul in 1994, Erdoğan was an effective and pragmatic mayor (Dagi Reference Dagi2008). Nonetheless, he was removed from office in 1997 after reading a poem; the following year, the Welfare Party was banned as a threat to Turkey’s secular order, and Erdoğan himself was jailed for four months, which served to increase his credibility and popularity (Guiler Reference Guiler2021). While many of the Welfare Party’s committed Islamists formed the Felicity Party, with MUSAID’s support Erdoğan co-founded the Justice and Development Party (AKP), a more centrist, pro-European party that won the 2002 elections.

Initially, many praised the AKP’s liberalism as it began reducing social and legal discrimination against religious individuals and rolled back the military’s power (Özden et al Reference Özden, Akça, Bekmen and Tansel2017). In 2005, the European Union and Turkey started accession negotiations, reflecting the AKP’s neoliberal and developmentalist orientation. As the AKP initially won during an economic crisis rooted in capital flight, maintaining high rates of foreign investment became a priority. Along with the massive inflow of international finance came a real estate boom (Erensü and Karaman Reference Erensü and Karaman2017). Changes to laws on metropolitan municipal governments gave them more power over development, drastically shrinking the powers of district municipalities and oversight agencies. As the AKP controlled most metropolitan municipalities, this allowed for more discretionary interventions by the central government. Developers with close ties to the center could get favorable deals on land and infrastructure, construction companies contributed financial support to local campaigns, and the AKP could steer projects in ways that benefited them politically. This system was further enhanced when the Public Housing Administration (TOKI) was brought under the Prime Minister’s office, and over time the percentage of affordable housing it built declined as its luxury housing portfolio increased (Ark-Yildirim Reference Ark-Yıldırım2017; Demiralp Reference Demiralp2018).

Opening the Turkish economy to the world and shifting to capital intensive sectors produced growth, but the AKP had additional strategies to build its strength. Social assistance, including conditional cash transfers, health care, and other need-based aid, rose dramatically after 2002. Some was funneled through municipalities, and AKP municipalities in particular developed robust social assistance programs. Aid also came through Islamic charities, many of which have close ties to Erdoğan’s circle (Yörük Reference Yörük2012; Özden et al. Reference Özden, Akça, Bekmen and Tansel2017; Esen and Gumuscu Reference Esen and Gumuscu2019). In neighborhoods, AKP activists were often visibly involved in aid programs, helping establish the conditions for clientelism (Ark-Yildirim Reference Ark-Yıldırım2017). The AKP created a network of allied organizations beyond charities. MUSIAD and TUSIAD often agree on economic policies; but when they differ, it reflects their different ties to Erdoğan more than their different membership profiles. As one entrepreneur active in TUSIAD noted, they are treated well when they agree with Erdoğan and are demonized as part of the cosmopolitan elite when they do not (Entrepreneur 2022). There are new AKP-tied women’s rights organizations that claim to focus on women’s real interests instead of an elite feminist agenda (Yabanci Reference Yabanci2016; KADEM 2022). Similar to MUSIAD, the labor unions Memur-Sen and Hak-Is were formed by religious individuals before 2002 but saw their membership and power increase dramatically after. They both reinforce AKP rhetoric, including the importance of labor harmony and how ideas of class struggle are antithetical to Turkish values (Özden et al. Reference Özden, Akça, Bekmen and Tansel2017; Tanyilmaz Reference Tanyılmaz, Balkan, Balkan and Öncü2015).

These efforts at building a vertical network with allied organizations coincided with efforts to reconfigure Turkish identity. Rejecting Atatürk’s vision of a secular “Turkish” identity, the AKP sought to build a multi-cultural, Turkey-center Islamic identity that both privileged certain Sunni religious groups and allowed for religious and ethnic minorities (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2018). Instead of being a recreation of the Ottoman millet system, it is a modern reinterpretation that still gives the government a central role in managing group relations. This vision of a “New Turkey” led to new policies and rhetorics toward the Kurds, Alevis, and other minority groups. The Kurdish Opening refers to Erdoğan’s initiatives toward Turkey’s Kurdish population from 2004 to 2013. The policy changes permitted the broad use of the Kurdish language in education and the media, but as important were the ways Erdoğan emphasized that the Kurds were fellow Muslims (Aktürk Reference Aktürk2018; Kaftan Reference Kaftan2022). By trying to bring the Kurds into a multicultural Islam, the AKP tried to create a contrast with the historically more Turkish nationalist Republican Party and to distance the community from the HDP, a leftist party largely supported by Kurds. Similarly, the Alevi Opening in 2009–2010 aimed to address the ways this religious minority had been made invisible by the state over decades (Arkilic and Gurcan Reference Arkilic and Gurcan2021).

This multicultural Islam strategy reassured Europeans worried about minority rights in Turkey; it was also an effective electoral strategy for a number of constituencies. Arguing that Erdoğan views democracy as electoral mandates, some date Erdoğan’s clear turn toward illiberal populism to 2011, the year the AKP won 50% of the parliamentary vote (Öniş Reference Öniş2015). Refiguring the complicated civic and ethnic boundaries helped the AKP grow its voter base, but it also created exclusions in ways reminiscent of earlier periods of Tukish nationalism (Goalwin Reference Goalwin2017). The urban transformations also were popular, a visible sign that Turkey was developing into a modern economy. Still, urban governance without widespread consultation had a cost. Increasingly, informal settlements on public lands were targeted for redevelopment. Neighborhood associations sprung up to defend their interests. Even as some residents were guaranteed apartments in the new development, over time neighborhoods dug in to widen residents’ rights and halt displacement (Genc Reference Genç, Erdoğan, Yüce and Özbay2018; NGO Activist 2022).

There had already been scattered resistance to Istanbul’s redevelopment when the Gezi Park protests started on May 27, 2013. The spark was a plan to build a large shopping mall resembling an old Ottoman barracks on it; Kalyon Group, a company with close ties to President Erdoğan, was the lead developer (BBC 2013). Spreading nationwide, 2.5 million people participated in 5,000 demonstrations. The protests themselves galvanized diverse groups for different reasons. Anti-capitalist Islamists, communists, and others came out to protest Turkey’s economic model, and monetary exchange was banished from the park. Those who felt marginalized by the government’s nationalist and Islamist rhetoric demonstrated. The brief Alevi Opening seemed to disintegrate in 2011 when Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, an Alevi, became chair of CHP, long the dominant opposition party and rooted in Kemalism, and large numbers of Alevis protested at Gezi (Arkilic and Gurcan Reference Arkilic and Gurcan2021). The Gezi Park calls even resonated in smaller towns that had been ecologically damaged by extractive industries or redeveloped for tourists. While the diversity of the protesters caused tensions, the self-organization and participatory governance inside the park created the “Gezi Sprit” (Erensü and Karaman Reference Erensü and Karaman2017). The NGO Activist (2022) stated that one could see the faint line from Gezi to İmamoğlu’s election. While the protesters were dispersed, new groups sprung up that focused on neighborhood issues, organized community events and nature classes, and monitoring elections. Overall there was a sense that, to borrow Henri Lebvre’s phrase, there was a “right to the city,” citizens were empowered to be involved in creating it, and moving beyond polarization, including ethnic and religious divisions, was key (NGO Activist 2022; Zihnioglu Reference Zihnioglu and Youngs2019).

Even so, the period between the Gezi Park demonstrations and the 2019 local elections were a tumultuous time in Turkey. The AKP did not win a majority in the June 2015 elections, and instead of allowing the opposition to attempt the form a government, new elections were held. Related to this, the relative peace in the Kurdish regions fell apart in 2015, loosening the ties between many religious Kurds and the AKP (Günay and Yörük Reference Günay and Yörük2019). The end of the Kurdish and Alevi Openings allowed for an open alliance between the AKP and the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). The alliance, which included the MHP supporting the 2017 referendum on moving from a parliamentary to presidential system, split the MHP with those supporting maintaining the parliamentary system forming the Good (IYI) Party. In 2016, there was an attempted coup, followed by massive purges from state institutions, including in Istanbul. Throughout this period, Erdoğan consistently chose to deepen the illiberal populist nature of the regime and reconfigure the communal boundaries so they encompassed less ethno-religious pluralism.

Istanbul’s 2019 Mayoral Election

The opposition believed winning metropolitan municipality governments could significantly dent the ruling regime. Turkey is divided in 81 provinces, under which are districts. Istanbul is one of 30 metropolitan municipalities, which means the metropolitan and provincial boundaries are the same; metropolitan municipalities also include rural areas, which are more likely to vote AKP. Istanbul is further divided into 39 municipal districts, each of which has its own mayor and elected council. While the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IBB) mayor is directly elected, the council consists of district mayors and some district council members. The council, which is chaired by the mayor, is relatively weak, but it does control the budget and can evaluate policies (Babaoglu Reference Babaoglu2019). Primary responsibilities of the metropolitan municipality include the city’s strategic plan, major roads and squares, transportation, utilities, environmental protection, and police (Göktolga and Ekici Reference Göktolga and Ekici2016). The IBB is a huge operation with about 85,000 employees and a budget of $10 billion. This number includes not just those working directly for IBB, but also those working for one of its many subsidiaries.

The opposition viewed Istanbul as within reach. First, there was no elected incumbent as mayor. Kadir Topbaş (AKP) was mayor from 2004 to 2017. Even after famously stating that Gezi Park’s redesign had been done by Erdoğan, not the city, he managed to win reelection in 2014 with just under 50%. However, he was forced to resign in 2017 in the shakeup after the attempted coup. The city council named Mevlut Uysal (AKP), District Mayor of Başakşehir, over İmamoğlu (CHP), who at that time was District Mayor of Beylikdüzü. Second, the Turkish economy was slowing dramatically. Third, there were a number of controversial projects in Istanbul as well as issues that never seemed to get solved. While the expensive new airport, with the politically connected Kalyon Group as the lead developer and inconveniently located in the municipality’s northeast corner, had some appeal, the canal project is hugely controversial. The plan is to build a new canal from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara on the western edge of Istanbul. While Erdoğan declares it vital for combating the overcrowded Bosphorous, opponents view it as a boondoggle designed to increase the value of huge tracts of undeveloped land along the proposed canal route that is under the central government’s control (NGO Activist 2022; Urban Planner 2022).

Three perennial issues are traffic, low-cost housing, and handling of the Syrian refugees. The city invests huge sums in transportation, but it primarily goes to megaprojects like the metro expansion, the new airport, and new tunnels and bridges across the Bosphorous (Canitez et al. Reference Canitez, Alpkokin and Kiremitci2020). As the city encountered so much neighborhood opposition in redeveloping the urban core, it opted for expanding the footprint of the city, and the transportation investments have never kept up. And little building was aimed at affordability; by 2018 only about 5% of the housing built by TOKI in Istanbul was “social housing” (Urban Planning Administrator 2022). The clear issues for İmamoğlu were stopping the canal, investing in affordable housing, greening the city with parks and better transportation, and acknowledging the refugees’ impact on infrastructure, housing, and the labor market.

For the 2019 local elections, the coalitions for the 2018 presidential election broadened. Former Prime Minister and current Parliamentary Speaker Binali Yildirim ran as part of a coalition with the far-right MHP. On the other side, İmamoğlu was the CHP and the small Good Party (IYI) candidate. The HDP decided not to run a candidate, but it also did not endorse İmamoğlu. While an endorsement could have been politically problematic for İmamoğlu, the HDP also views him as too pro-capitalism and the IYI as discriminatory toward Kurds; still, it signaled that its supporters should work to defeat the AKP candidate (Celep Reference Celep2019; HDP 2023). Critically, İmamoğlu and the CHP decided not to attack Erdoğan and the AKP, but to counter the pernicious polarization with a campaign of “radical love” (Wuthrich and Ingleby Reference Wuthrich and Ingleby2020; Öktem Reference Öktem2021). Conscious of his language, he spoke of “new start” for the city instead of change, and, by talking about love, connection, shared values, and freedom for all, he broadened the idea of “the people” to include a broad range of diversity in Istanbul. Alluding to how the well-connected gobbled up green space and land in low-income neighborhoods for expensive redevelopment or otherwise benefitted from lucrative contracts, he spoke of “waste” that prevented fair and efficient use of resources (Demiralp and Balta Reference Demiralp and Balta2021). He said the refugee issues had been “badly managed” (BBC 2019). He visited mosque and tombs to show he was not anti-religious. His extensive social media campaign was flooded with pictures of him interacting with diverse groups at campaign events or doing his job as district mayor; occasional pictures of him with his family or shopping added a human touch (Melek and Müyesseroğlu Reference Melek and Müyesseroğlu2021; Uluçay and Melek Reference Uluçay and Melek2021). In these ways, he reassured Erdoğan supporters that they could support Erdoğan as president and him as mayor.

In contrast, Yildirim was nearly invisible as Erdoğan and his team took charge. Continuing past polarization strategies, they blasted İmamoğlu as an ineffective district mayor who was allied with dangerous radicals and would drastically cut social services (Esen and Gumuscü Reference Esen and Gumuscu2019; Yavuzyılmaz Reference Yavuzyılmaz2021). On election-day in March 2019, İmamoğlu narrowly won by about 13,000 votes out of over 8.5 million cast. According to Vote and Beyond (2022), the rigorous election-day monitoring ensures an accurate count. Even so, under pressure the Supreme Electoral Council annulled the mayor’s race for suspicious activity (although letting all other Istanbul races stand) and ordered a June re-run. While the AKP shifted to local issues and Yildirim ran an active campaign, minor candidates who had run in March mostly pulled out, and it was clear that AKP was beatable; in June, which had even higher turnout, İmamoğlu won 54% of the vote, a margin of 800,000. However, the votes clearly were for İmamoğlu and not the CHP as it lost seats on the city council, which remained in AKP hands (Istanbul City Council Member 2022).

Istanbul under İmamoğlu

The CHP not only won Istanbul, but other large cities including Izmir and Ankara. Sixty percent of Turkey’s population now live in CHP-run cities. The mayors, particularly İmamoğlu, faced enormous pressure to show their administration would be different in style and substance. At a July 2019 workshop for elected CHP mayors, the party leadership laid out several core principles, including embracing all local residents equally, financial transparency, no clientelism, meritocratic appointments and hiring practices, and attention to disadvantaged neighborhoods and groups (Celep Reference Celep, Celep and Kurt2020). For İmamoğlu, public participation became a hallmark. It came up repeatedly in interviews, and one interviewee indicated it had almost gone too far as they spent so much time in consultative meetings and commenting on policies proposals that they had trouble focusing on their own priorities (NGO Activist 2022). The rationale for public participation is clear as an inclusive process can reduce polarization, increase policies’ legitimacy and effectiveness, and help the city shape its communication; it is also low cost. Interviewees also consistently said the mayor was in a hurry to get things done to quickly demonstrate the new start, to have a record in case there were early elections, and to make changes in case he was removed from office like many HDP mayors (Tutkal Reference Tutkal2022). This section discusses in detail the actions by the city and the AKP around the four overlapping areas of information costs, horizontal ties with the local government, depolarization, and vertical ties between clients and the central government.

Access to Information and Communication

Effective citizenship requires easy access to clear and relevant information. The mayor’s office has emphasized communicating the city’s on-going activities and plans, which also spreads positive messages of progress (Mayoral Administration Employee 2022). According to Öktem (Reference Öktem2021) and the author’s research, the IBB Bulletin, the city’s free monthly magazine, shifted attention from mega-projects and Erdoğan to profiles of city workers and smaller, local projects that speak to specific constituencies, such as university dorms, social programs for women and children, expansion of public internet, new buses, and greening efforts. Similar to the campaign, its profiles and visual images portray the ethno-sectarian diversity of the city while not explicitly drawing attention to difference. The IBB Bulletin does not entirely ignore controversies involving the central government, such as the canal project, and sometimes directly addresses rumors about the mayor’s office. The IBB Bulletin and social media, however, are small efforts compared with the larger media outlets still favorable to the AKP.

More important than the information the mayor’s office pushes out is the information and communication necessary for public engagement. The stress on increased information is encapsulated in the new Istanbul Planning Agency (IPA), which one employee (2022) described as a consulting agency for the Mayor’s Office. Their statistics office collects data from a myriad of sources for their reports, but they also make it more accessible. Because of their expertise in public participation, they work with subsidiaries and districts on their public participation efforts as well. The Istanbul City Council member (2022) emphasized that transparency and public participation are now central to the CHP’s image. Pointing to substantive internal debates and competitive nominating processes, he stressed how these values were practiced within the party as well as in governance. The downside is that it opens the party to narratives they are always fighting, so İmamoğlu has explored ways to curtail open bickering.

The two-way communication practiced across the IBB was clear in the interviews. For example, a project manager in the IBB Planning Department (2022) detailed both the new opportunities and challenges in public participation. For large projects like redeveloping major squares and piers, the plans are online and there are opportunities for extensive online comments in addition to public meetings. For smaller projects, there will simply be neighborhood meetings in which they will invite residents, local NGOs, and district officials. In addition, there is now a phone number people can call to suggest or offer land for small parks. Another urban planning administrator (2022) noted that previously the IBB Urban Planning Department had almost no contacts with districts, but now they are in frequent communication with them as well as NGOs, residents, and neighborhoods. In addition to online information, they open a small office in areas with major projects to facilitate constant communication with the neighborhood. A project manager at Imar (2022), an IBB subsidiary focused on development, also noted that there is a much greater focus on parks and kindergartens in their projects, which responds to both the mayor’s priorities and public feedback. They also now have a way for residents to report at-risk buildings. Finally, when the author came out of an interview at Halk Ekmek, the bread subsidiary, a group of residents was waiting to talk about getting more Halk Ekmek kiosks in their district, illustrating their belief IBB was accessible.

The extent to which the value of public participation has been driven through the IBB was impressive. But this communication has uses beyond the specific projects. The years out of power gave the CHP time to consider their past and their future (Istanbul City Council Member 2022). In reinventing themselves, this formerly top-down Kemalist party now needs to work bottom up. Public participation helps keep them in touch with the grassroots, which in turn shapes their policy proposals in city council sessions. According to an Istanbul City Council member (2022), as the AKP holds the majority and will not support their proposals, they use the city council sessions to communicate to the public. Because of this, they are careful not to fight with the AKP as it drowns out their policy explanations.

The AKP, on the other hand, tries to fill the news with accusations and supposed scandals. Stories to maintain polarization are discussed below, but, for a well-known example around IBB’s management, videos of overcrowded buses during the pandemic and passengers pushing buses were widely shared on social media despite evidence some were staged. Such stories serve to crowd out the city’s information, make the city less desirable to engage with, and demobilize citizens.

Building Effective Horizontal Ties

“Promises made, promises kept” is an important theme of the mayor’s media campaign, and access to information and increased communication are vital. But these efforts are insufficient if individuals do not feel heard on an ongoing basis, if they cannot link their participation to what the city does. An NGO Activist (2022) noted that there was so much consultation and insufficient follow-up, reflecting both the city’s rush to get things done and lack of capacity to circle back to groups, that their impact is often hard to see. Still, he related the story of an animal rights activist who had long protested the treatment of horses pulling carriages on Princes’ Islands. After the 2019 election, she renewed her protest in front the municipal building. Within a month the city had an agreement with her and the horses’ owners on shutting down the carriages, a story the IBB could use to demonstrate impact. While government interviewees were proud of their ability to respond to the public, they also had stories of unrealistic demands, problematic expectations, and conflicting desires. The urban planner (2022) gave several examples: a neighborhood with many small NGOs wanted a metropolitan-funded conference center larger than any of them could realistically use, small farmers wanted an expensive irrigation system despite the water shortage, and a neighborhood fought transforming a derelict lot into a pocket park out of fear it would spark gentrification. The project development manager at Imar (2022) talked about running up against past practice. When they redevelop an area, existing residents are offered a unit of similar size in the new development; and even while adding some housing, they try to maintain the neighborhood’s scale and density. In previous administrations, they would build giant new buildings and compensate people with multiple apartments that could be used by family members. Now that Imar is following the city regulations, reportedly people are upset that they only get one apartment.

Managing expectations is one challenge in forging and maintaining horizontal ties. Effective horizontal ties also require significant capacity in both the government and civil society. When the opposition took power, they did not have a bureaucracy with the skills and mindsets for rapid change. Beyond unconfirmed stories of numerous ghost jobs in the past, clearly there had been minimal expectations for improvement. For example, employees at Bilbim (2022), the subsidiary responsible for the Istanbul transportation card, praised the R&D department’s long-standing strength, but added much of its work had never been applied. An employee who started before 2019 described the current environment as more focused on new financial technology, more collaborative across the company, more transparent, and absent even slight hints they should be involved with certain political parties. All of the new employees came from the private sector because of the exciting new projects. While they recognized İmamoğlu’s priorities took precedence, such as using the cards for COVID-19 tracing and adding specialized benefits for low-income women, they were energized by the combination of innovations requiring rapid turnaround and longer term entrepreneurial projects.

Bilbim was not the only place with new, empowered employees. The urban planner (2022) had been at a firm whose contracts dried up in the pandemic. He had been locally active in the CHP, but stressed he applied online like everyone else, which echoes reports of the IBB’s emphasis on hiring well-qualified employees (Öktem Reference Öktem2021). While considerable design work on his projects, which started before 2019, had been contracted out to private companies, he said now his department’s skill-level had increased so much that they would do it all in house. The entrepreneurialism at Halk Ekmek seemed similarly unleashed. The number of kiosks selling their inexpensive bread had remained at about 500 for decades, a policy that was popular with private bakers as Halk Ekmek keeps the market price of bread down. But there was enormous unmet demand from both the economic downturn and the long-term population growth (Halk Ekmek Administrator 2022). Initially, the city council tried to block new kiosks but presumably retreated as the kiosks would primarily go into AKP districts (Öktem Reference Öktem2021). To fund the significant increase in basic bread production, which operates at a loss, they expanded the higher-end and gluten-free products, which make money (Halk Ekmek Administrator 2022). The newly created IPA helps ensure coherence and deep analysis to the efforts to make Istanbul a fairer, more open, and greener city. About a third of its 80 employees worked elsewhere in the IBB, but the rest are academics and activists (IPA 2022); one social activist (2022) said if one wanted to find Gezi Park protesters in IBB, the IPA would be the place to look. This mix was deliberate both to ensure it was situated amidst dense horizontal networks and to bring together people who knew how the city did work, how it could work, and how citizens want it to work (IPA 2022).

With the city’s increased capacity and outreach, the two NGOs interviewed also seemed invigorated. Since its founding, Vote and Beyond (2022) has focused almost entirely on election monitoring. While they are applying for grants to enhance technology use in election monitoring, its new board members are increasing attention to the word “beyond” in their name. The organization is politically neutral, but the deeply polarized environment with frequent elections and referenda constrained their ability to expand their activities. With a changed political environment, they are imagining new programs to deepen Turkish democracy, especially ones targeting university students and groups facing discrimination. The Center for Spatial Justice is also expanding its activities (NGO Activist 2022). With a current focus on urban policies and environmental justice, they have been assisting districts with their participatory programs, helped run some of the participatory budgeting meetings, and, as a way to enhance community cohesion and identity, worked with neighborhoods to create walking tours with historical narratives and photos. The center also works with the reinvigorated City Councils, which are advisory bodies to the municipalities that bring together local officials, mukhtars, NGOs, and others and were meant to build horizontal linkages, enhance a sense of urban citizenship, and help bring issues to the municipality (Göktolga 2016).

The central government has tried to limit these horizontal ties by undermining the metropolitan municipality’s effectiveness and the public’s perception of it. The previously mentioned scandals and investigations are part of this. What has happened in public transportation is particularly illustrative. Previous administrations announced dramatic expansion plans for public transportation, particularly the metro system. When İmamoğlu became Mayor, the government refused to commit additional money for the city’s transport plans and the AKP-dominated city council blocked the metropolitan municipality’s efforts to borrow money for it (Öktem Reference Öktem2021). The IBB Bulletin still reports on these projects’ importance, but the limited funds slowed metro construction and the purchase of cleaner busses. As the airport metro line neared completion, the central government took credit. In November, the Minister for Transportation and Infrastructure, on hand for test run, was quoted as saying, “We want to build a mass transit system in Istanbul where people will not have to push broken-down buses” (Daily Sabah 2021). Activities around open space also shows how the central government can assert its power. The most dramatic example is the government taking Gezi Park from IBB, which will be discussed below. There are also the Gardens of the Nation program. While this presidential initiative started after the Gezi Park protests, it intensified after the local elections. Essentially, it is a parallel way to create parks on government land (NGO Activist 2022). While most are well maintained, IBB provides additional services when the district lacks the capacity to keep them up even though the president largely gets the credit for the proliferation of parks across the city (Urban Planner 2022).

Depolarization and Social Solidarity

Instead of a “passive depolarization” that merely seeks to avoid the regime’s polarization (Somer et al. Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2021), the IBB under İmamoğlu has actively promoted the idea of a city for all. The IYI party official (2023) was particularly effusive in praising İmamoğlu as the Mayor of all Istanbulites, specifically mentioning how he is creating “solidarity” in the city. Contrasting him with the previous mayor, who reportedly said he would build subways to districts that supported him, İmamoğlu has completed subway lines to AKP districts. Echoing the Halk Ekmek official discussing their new stores in AKP areas, the IYI party official (2023) pointed to all the new kindergartens in AKP areas.

Their commitment to strengthening social solidarity also came through in their response to the economic crisis accompanying the pandemic. Simply, they asked for public donations so neighbors could help neighbors. Donations, which came from individuals as well as the business community, were intended to fund new kindergartens, stipends for students from low-income families, and other kinds of pandemic relief. The reliance on businesses did raise questions as to whether businesses were building ties in case the CHP wins nationally or whether it was businesses who had previously been shut out by IBB (Öktem Reference Öktem2021). In April 2021, the central government declared donation programs organized by metropolitan and district municipalities illegal without their approval and seized the money. A month later, İmamoğlu responded with Pay-It-Forward, which allows individuals to directly and anonymously pay online the bills of low-income families. Hailed as a way to build social solidarity across the city, it gained international acclaim, winning a 2021–2022 Bloomberg Global Mayors Challenge Award for innovative responses to the pandemic.

As noted earlier, the İmamoğlu campaign and subsequently the IBB media outlets have been deliberate about showcasing the diversity of the city. Illustrating the IYI’s rhetoric, the IYI official (2023) said, “you can find every color of society in this city,” called the Kurds a founding element of Turkey and the Alevis as “citizens who are loyal to Atatürk,” and noted they all “fought shoulder to shoulder for liberation” (IYI 2023). But this does not mean everything is fine. The HDP official (2023) was less effusive, first pointing to the IYI’s discriminatory comments toward the Kurds and how they have openly said they would not appear together with the HDP. Viewing the İmamoğlu administration as far preferable to the AKP, the HDP official still did not feel they were entirely welcoming to all, specifically mentioning feminists, labor, and the queer community among those not fully embraced. Furthermore, pointing to practices in HDP-controlled cities, they believed a truly inclusive administration would have councils for women, union members, and other groups to help set the agenda instead of merely asking for input on the mayor’s agenda. Still, they recognized how the mayor was constrained by the broader political context and that conversations around more radical ideas for making Istanbul more inclusive and participatory could not happen until the AKP lost at the national level (HDP 2023).

Through all this, the national government maintained its efforts at polarization, especially as İmamoğlu had been viewed as a potential challenger to Erdoğan in the 2023 presidential election. Building on whispering campaigns during the mayoral election that İmamoğlu is ethnically Greek and not even a Muslim, there were accusations of İmamoğlu disrespecting an Islamic tomb. In December 2022, İmamoğlu was convicted of defamation for saying in 2019 that election officials were “fools” for canceling the March 2019 mayoral election; under appeal at the time of this writing, the conviction carries a two-year prison sentence and a ban on holding political office. In another judicial attack on the CHP, their Istanbul branch head was sentenced to nine years in prison for Tweets criticizing Erdoğan and allegedly praising the PKK, although she never served the time (Öktem Reference Öktem2021). More worrisome, at the end of 2021, Turkey’s Interior Minister announced a special investigation into tips that over 500 terrorists had been hired by IBB, another accusation that could be used to remove İmamoğlu. An interviewee working on social programs for the Sisli Municipality (2022) noted that she constantly feels watched by AKP members looking to create a scandal. As the municipality has programs designed for LGBTQ+ individuals, they have been particularly careful with how they manage and talk about these programs; but since the terrorism accusations, she feels like almost anything could be mischaracterized to provoke outrage. The HDP official (2023) spoke of how initially the IBB would sometimes reach out to HDP as part of its effort to be inclusive, but this stopped after the Interior Minister’s comments; in fact, some IBB employees with ties to HDP were fired.

Disrupting Populist Power at the Local Level

To create effective partnerships, the new city administration not only needs to enhance its own and civil society’s capacity, it also needs to disrupt the implicit and explicit clientelism that structures the vertical ties from the local level to the center. Investigations into the previous administration represents one opportunity for this, but the IBB has rarely done this as it could exacerbate polarization. Still, the IBB and the municipal districts are key actors in real estate and social service provision, the two most important areas for the AKP’s clientelism (Yavuzyılmaz Reference Yavuzyılmaz2021). As a result, conflicts over them have generated some of the biggest headlines.

Large urban redevelopment projects have slowed in Istanbul both because they are not a priority of İmamoğlu’s administration, which instead has focused on more neighborhood-level projects and the pandemic’s impacts. Along with more open, competitive bidding, the resources of AKP-friendly construction companies have shrunk along with their donations to local officials. Still, the central government controls considerable land in Istanbul, including much of the land along the proposed canal, unused military property, and the former Atatürk Airport. While eyed for high-end development, the IBB advocates for these tracts to remain unbuilt, to be used for social housing, or, in the case of the airport, to be reopened; the IBB has very limited power over these decisions, but it can make its case to the public (Urban Planning Administrator 2022). The central government has rarely moved projects to agencies or levels they control, although Gezi Park is an exception. Recognizing that Gezi Park and Taksim Square remain poorly designed urban spaces, IBB launched a redevelopment project that involved extensive public participation, including online voting of designs by 200,000 people. The government then unexpectedly transferred Gezi Park to the Foundation of the Sultan Beyazıt Hanı Veli Hazretleri, which operates under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

In addition to the pandemic initiatives mentioned above, innovations around social services have drawn attention. While social services are generally paid for by the central government, local governments have important roles (Yavuzyılmaz Reference Yavuzyılmaz2021). For example, well-funded municipalities can develop additional programs, and the contracts with religious groups were with the municipalities. Despite campaign accusations, the author heard no reports of programs being reduced or even contracts being reexamined. Instead, the CHP-led municipalities have worked to expand coverage. A Sisli municipality employee (2022) acknowledged the CHP historically had paid limited attention to social services. They had already launched new pilot programs and were reaching out to colleagues across the city, including in AKP-led districts, to learn about initiatives that might be effective in Sisli. While lack of funding is a severe constraint, they were approaching international donors.

Disrupting vertical ties also means diversifying networks. This may mean new ties within the city, but it can also mean developing international relations. The search for international funding by Vote and Beyond, the Center for Spatial Justice, and the Sisli Municipality illustrate this impetus. For IBB and TUSIAD, it is a conscious strategy. One IBB priority is access to European financing (Mayoral Administration Employee 2022). While Turkey receives funding for subnational programs, including for refugee support, it goes directly to the central government. European financial institutions also will not sign loans with cities without central government approval. The mayors of Prague, Budapest, Warsaw, and other cities have collectively lobbied the European Union about changing these practices. The mayor’s office is also building ties with other global cities to show there is more to Turkey than Erdoğan; these connections may also open up international partnerships for Istanbul-based companies and NGOs. TUSIAD sees connecting the mayor to the European business community as a way to open doors for financing. It also sponsors a program that involves six European cities and six Turkish cities, including Istanbul and a couple with AKP mayors (Entrepreneur 2022). Similarly, though the ongoing meetings covering a variety of practical issues, their hope is not just that they learn from each other but that the ties generate spillover effects.

Conclusion

In a competitive authoritarian regime, a liberal democratic opposition winning the major city can set the stage for broader democratic change. The election victory itself provides hope that the ruling party can be defeated through elections, but the mayor’s office and the central government end up in a battle over information, the local government enhancing horizontal ties, the future of existing vertical ties, and degree of polarization. For İmamoğlu and the CHP, public participation was a key tool touching on each of these. Furthermore, reducing polarization was a likely impact of their efforts as well as a conscious goal they worked towards with their communication strategy and outreach. The city managed to increase its capacity in key areas through new hiring and greater expectations for entrepreneurial solutions, and there are signs that this was met with new innovations in the NGO sector as well. While it is unclear how successful IBB has been in disrupting vertical ties either through direct efforts to weaken them or by expanding alternative networks, the AKP was forced to respond to the city’s pandemic initiatives and has failed to deter opposition efforts to build ties with AKP voters and allied business.

This study identifies four core items to be examined in future comparative studies of liberal cities in illiberal regimes. How to measure progress in each area is also an important question for future research, but it is beyond the scope of this article. Furthermore, understanding the reasons for the extent of progress is key. While not definitive, this case offers several potential reasons for the significant progress of İmamoğlu’s administration. One is that while the opposition is a coalition, there is a dominant coalition partner instead of a range of small parties. This allows greater cohesion of messaging and action in Istanbul and among local CHP officials across Turkey. And despite any qualms about the CHP and IYI Party, the HPD seems to recognize the important cleavage is between an illiberal, populist regime and a more pluralistic opposition. Second, the IBB and the districts already had significant human capacity and administrative power. With new leadership and adding staff with new skills, the new administration could expect the bureaucracy to follow its new priorities, which in turn made the change in tone and efforts at inclusive engagement quickly visible. Finally, one cannot ignore İmamoğlu, who was consistently described as a charismatic politician who inspires action with his rush to get things done. Without further study, it is difficult to determine the relative importance of capacity, cohesion, and leadership.

The impact of pluralistic opposition mayors on national politics also remains unclear. National elections have different issues and electorate, which can be decisive even when the cracks in the populist regime radiates out from major cities. The evidence suggests that İmamoğlu and his team have taken advantage of the opportunities their electoral win offered, and his “radical love” and attempts to unify the city seem critical to this success. Still, İmamoğlu was not selected as the united opposition’s leader for the national elections. The failure to select İmamoğlu as the opposition leader and the meaning of this decision also need to be considered when studying the full impact of pluralistic mayors in illiberal regimes.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the incredible, invaluable support of Daglar Yarasir during this project as well as the comments of the reviewers.

Disclosure

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.