INTRODUCTION

Over recent decades most major museums have published their ‘Hundred Treasures’, ‘Director’s Choice’, or similar items in the genre. The Royal Armouries, which published Treasures from the Tower of London to accompany an exhibition in 1982 and is soon to produce a similar title, is no exception.Footnote 1 Selecting the ‘treasures’ was an interesting process, highlighting the variety of reasons for which an item might make the grade. In the case of the Royal Armouries, the parlance of heritage management was borrowed to assess the degree to which an asset might possess an agreed set of ‘values’ that, when added up, could quantify that asset’s overall ‘significance’.Footnote 2 These values go beyond the obvious typological, technological and artistic attributes of an object (or class of objects) to embrace those derived from that object’s association with past events and people, its impact on history and society, and its importance to particular communities or causes. Such objects may therefore have few intrinsic qualities as artefacts, while having a significance rooted in broad or particular aspects of history, human endeavour or experience in which they played a part or whose nature they illustrate.

Firmly in this category are the Royal Armouries’ two worn and battered scythe blades (fig 1), adapted and re-hafted to form the business ends of staff weapons for the Duke of Monmouth’s rebels in 1685, and picked up by the victors at Sedgemoor.Footnote 3 Of plausibly seventeenth-century origin, there is little reason to doubt that these were among the eighty-one ‘scith blades’ recorded at the Tower in 1686,Footnote 4 and which were, by 1694, described as spoils from the battle.Footnote 5 Crudely improvised, perhaps mere days before their capture, they recall the forlornness of Monmouth’s venture, are embedded in the popular image of Sedgemoor and have featured in its representation by artists (fig 2), historians and novelists ever since.Footnote 6 On a broader scale, they recall innumerable encounters in many countries over many centuries, in which desperate men with makeshift arms fought powers and professionals they could rarely hope to beat.

Fig 1. The Royal Armouries scythe blades, (a) vii.960 and (b) vii.961, showing the top ends of their (more recent) hafts. Photographs: © Royal Armouries.

Fig 2. The Morning of Sedgemoor (1905) by Edgar Bundy (1862–1922). The upright blade may be based on vii.960 (see fig 1). The artist shows the improvised nature of the weapon, the blade lashed to a crudely dressed sapling. Image: Tate/Digital Image © Tate, London 2014.

The general aims of this article, therefore, include calling attention to such struggles, parallel to but rarely included in the mainstream study of warfare, and of a specific but widely used weapon type that has received almost no attention from historians of arms and armour;Footnote 7 pursuing the subject, meanwhile, has been encouraged by the renewed interest in Monmouth following the appearance of Anna Keay’s 2016 biography,Footnote 8 the objects’ brief appearance in a recent exhibition at the TowerFootnote 9 and the discovery of a so-far unpublished account of Sedgemoor, rich in information on the ‘sithers’, written in 1688–9 by John Taylor, a Royalist volunteer.Footnote 10 A critical edition of the text by Professor John Childs, which has done much to inform this article, is published in conjunction with it.Footnote 11

More specifically, what follows starts with a description of the Royal Armouries’ items, their manufacture and date, then examines the quantity and type of Monmouth’s conventional armaments, his need to improvise and the methods of procuring and converting the blades, and is followed by some discussion of how the ‘sithemen’Footnote 12 were deployed in the campaign and at Sedgemoor. The article also briefly examines the military use of re-hafted scythe blades in Britain and Western Europe from the late Middle Ages to the twentieth century and their effectiveness. A final section summarises the history of the storage, display and description of Monmouth’s scythes at the Tower of London since 1686.

SCYTHE BLADES AT THE ROYAL ARMOURIES

The Royal Armouries possesses four weapons incorporating scythe blades. Two of these (vii.1745 and vii.2041) were created in the nineteenth century for display purposes and have been on view since 1996 in the Hall of Steel in Leeds.Footnote 13 These relate only loosely to this article, which centres on the other two: vii.960 and vii.961.

The first is a complete ‘crown’ blade, forged from a bar of wrought iron with a cutting edge of steelFootnote 14 (as opposed to the riveted or ‘patent’ form introduced in the 1790s)Footnote 15 and stiffened by an integral square-sectioned ridge or ‘chine’ at the rear of the upper side. It measures 97cm from tip to heel, and 6cm across at its approximate centre. Close to the heel is a hole to take the wire or ‘grass nail’ linking the blade to the snath (handle), which adds rigidity to the whole and prevents cut stems bunching up between the heel and the blade, and a second hole with the same function accompanies it, 3cm closer to the blade edge and 2cm closer to the tip. Beneath the hole is a letter composed of four punched marks, accompanied by a horizontal line, probably identifying it as a ‘W’ not an ‘M’. The worn and irregular profile of the blade’s edge indicates heavy use before re-hafting and, while at the Tower, it has been given at least one coat of black paint. The tang – originally at right-angles to the blade – has been bent to become axial to it and is socketed into a drilled hole at the end of the haft. Clearly fitted for display purposes after the loss of the original, the haft is 160cm long and 35mm in diameter, is of turned ash, stained and painted, and formerly belonged to another weapon, probably a naval boarding pike.Footnote 16

The blade of the second weapon, vii.961,Footnote 17 also of crown form, is 73cm long and 78mm wide, although missing its heel and tang. This has the same type of chine as vii.960, although extending closer to the tip, and is fixed by two nails into a 10cm-long slit in the haft, itself 186cm long, of turned ash, 33mm in diameter and stained to a dark mahogany colour. This too is re-used, and has a shoe in the form of a slightly tapering brass cylinder.

The form of the blades is important in considering their Sedgemoor credentials, otherwise based on circumstantial documentary evidence and tradition: while there is no established typology of English scythes, it seems that while Roman and early medieval blades were wedge-shaped in section, like a kitchen knife,Footnote 18 from at least the twelfth century they could be thinner but reinforced with a raised ridge or ‘chine’ at the rear;Footnote 19 by the nineteenth century the chine was being made flush with the upper surface of the blade but divided from it by a channel or ‘fuller’, together called the ‘whale’. This arrangement persisted in England, alongside the riveted variant, until production ceased in the 1980s; the widely used but shorter and heavier ‘Austrian’ scythe, still made today, is of similar form.Footnote 20 That the Armouries blades belong to the intermediate type is therefore consistent with, and may be said to support, the simplest interpretation of their provenance – that they were indeed picked up from the battlefield. As for their manufacture, being of a form that could be produced by any blacksmith suggests a local, West Country origin; if not, they might have come from specialist water-powered workshops in Worcestershire or Sheffield, active since the fourteenth century, but whether their products had reached Somerset by the 1680s is unknown.Footnote 21

MONMOUTH’S WEAPONS

The story of James, Duke of Monmouth (1649–85) and his rebellion has been told many times.Footnote 22 For present purposes it is enough to recall that he was the illegitimate but protestant son of Charles ii and Lucy Walter, and was persuaded by a number of disaffected parties in the spring of 1685, while in exile in Holland, to rebel against his newly succeeded and catholic uncle, James ii.Footnote 23 Monmouth landed at Lyme Regis on 11 June 1685Footnote 24 with a supply of arms and armour borne by two small cargo vessels (one ‘commanded’ by Mr James Hayes)Footnote 25 and eighty-two men, mostly aboard the Helderenberg, a 32-gun fifth-rate under Cornelius Abraham van Brakell.Footnote 26 Attracting at his high point up to 7,000 recruits,Footnote 27 the duke scored some initial successes, but the rebels were crushingly defeated by the royal army at Sedgemoor on 6 July and the duke was captured forty-eight hours later.Footnote 28 He was executed on Tower Hill on 15 July, about 320 of his followers elsewhere,Footnote 29 and a further 850 were transported during and after the Bloody Assizes.Footnote 30

While it is often said that the rebellion was foredoomed, Monmouth had some gifts as a leader, a good military recordFootnote 31 and had previously, as Captain General of the Army in 1679, prepared at least one detailed and costed list of equipment for a seaborne expeditionary force.Footnote 32 As such, although short of time and money, he took an informed interest in munitions and supplies, exercised through the agency of Nathaniel Wade, a Bristol lawyer-turned-soldier.Footnote 33 According to Wade, in May 1685, the duke went to Rotterdam to raise money and

in the meantime left orders … to provide two small ships and about 1500 foot arms, 1500 Curasses, 4 Pieces of Artillery mounted on field carriages, 200 as I take it barrels of Gunpowder with some small quantity of Granado shells match and other things necessary for the undertaking … Footnote 34

The two ships and material were ‘provided’ at a cost of ‘near £3000’ – presumably purchased – although the crews were Dutch;Footnote 35 the use of the Helderenberg, chartered after learning that ‘several of the King’s men of war were on the Coast’, cost Monmouth an additional sum of about £2,500.Footnote 36 The small ships were subsequently captured off Lyme on 20 June by Captain Richard Trevanion RN of the Saudadoes,Footnote 37 and the Helderenberg seized at St Ives, en route for Spain, probably on 29 or 30 June.Footnote 38 She was commissioned into the Royal Navy in 1686, but sank two years later after a collision.Footnote 39

A second account of the equipment procured in Holland, by Lord Grey, Monmouth’s co-conspirator and cavalry commander, appeared in his Secret History of the Rye House Plot and Monmouth’s Rebellion, written in 1685 at the king’s request, although published only in 1754.Footnote 40 According to this the

preparations … were as follows, 1460 suits of defensive arms; 100 musquets and bandaliers; 500 pikes; as many swords; 250 barrels of powder, besides what was provided for the frigate; a small number of double carabins and pistols, the quantity of them I cannot remember: our frigate carried two and thirty guns, and we had besides four small field-pieces.Footnote 41

The lists are, with one proviso, usefully complementary. Wade’s account can be taken to mean that foot arms were bought for 1,500 infantry, while the 1,500 ‘Curasses’ – by 1685 long discarded by pikemen and hardly ever worn by musketeers – were intended for cavalry, who then still wore breast, back and potFootnote 42 (known then and now as ‘harquebusiers’ armour’), as Monmouth and Grey did themselves.Footnote 43 The deposition of Mr Williams of 16 July 1685 helps to confirm this in mentioning the ‘1500 horse arms’ acquired in Amsterdam.Footnote 44 Some of this material also seems to have been taken to the Tower of London after Sedgemoor, from where it was committed to auction on 8 April 1717, comprising 602 ‘Backs with culetts’, 529 backs without culets, 1,085 ‘Potts’ and 910 ‘Breasts repair’d’,Footnote 45 that is, a large but mismatched assemblage of 1,131 backs, 1,085 helmets and 910 breastplates. The number is comfortably within Wade’s 1,500, although the armours as sold must have been mixed with others, as Monmouth’s harquebusier’s equipment would not have included culets, which were components of ‘cuirassier’ harness and long obsolete by 1685; possibly the Board of Ordnance batched all this material together in the hope that a Monmouth connection might enhance its value.

How much of the imported armour was actually used is another issue; as we know that only ‘300 horse’Footnote 46 marched out of Lyme, and given that carts were in short supply, most of it was probably left behind. The report by the Royalist gunner Edward Dummer that, on arrival at Lyme on 20 June, he found ‘Back and Breast and Head pieces for betwn. 4 & 5000’ in the townFootnote 47 supports this, although the mismatch between his figure and Wade’s, as well as that of 1717, is best explained as an exaggeration.

Armour, though, was less important than weapons. From Grey’s account we learn that the cavalry was supplied with a number of pairs of pistols and carbines (that is, short-barrelled, snaphaunce muskets), and that the foot arms included standard-issue weapons for pikemen (swords and pikes) to the number of 500. Grey’s account, however, is at first sight puzzling in noting only 100 muskets, but, as John Tincey has suggested,Footnote 48 it would make much more sense if the figure were a misprint for 1,000 (it appears at the end of the line), in which case Wade’s purchase would have equipped 1,500 men according to the standard proportion of 2:1 musketeers to pikemen. This also tallies with the c £3,000 budget, as at a rough estimate the muskets, swords, pikes and armour would have cost about £2,400, leaving a plausible £600 to cover the cannon, cavalry arms and the two smaller ships.Footnote 49 As Wade tells us, this equipment was mostly successfully unloaded, although forty barrels of powder were left behind on the transports:Footnote 50

Our Company was by the Duke divided into 3 parts, 2 thirds whereof were appointed to guard the Avenues of the Towne. The remaining third was to gett the arms & amunition from on board the ships my part of it was to gett the 4 peices of Canon on shoare and see them mounted which I performed by break of day having good assistance of mariners and townsmen.Footnote 51

Additional muskets and powder were seized in Lyme, on the day of landing, from the town arsenal.Footnote 52 The cannon were probably three-pounder ‘minions’,Footnote 53 although as shot have been found on the battlefield of 1lb 8oz and 12ozFootnote 54 (the second of which would have fitted a 1½ inch ‘robinet’Footnote 55), which could not have been fired by the other side, they may have been of mixed gauges.

The expectation was, however, that the recruits to Monmouth’s army would themselves provide far more weapons than he could bring, as Monmouth had been assured by his unreliable accomplice John Wildman and the spy Robert Cragg earlier in the year.Footnote 56 But this was not to be, largely thanks to the absence of gentry volunteers. Nevertheless, other means of acquiring conventional weapons enjoyed some success. On at least one occasion (25 June) equipment was taken from the Somerset militia, whose retreat, Wade tells us, ‘was little better than a flight, many of the souldiers coats and arms being recovered & brought in to us’.Footnote 57 Mr Williams’s deposition of 16 July 1685 mentions that ‘severall of the militia of dorset and somerset came in with their arms’,Footnote 58 and other militia weapons were seized from their stores, as at Taunton on 18 June.Footnote 59 Arms were also seized from ordinary houses, as revealed for example at the trial of Matthew Bragge, who had led a party to a catholic household for this purpose.Footnote 60 Great houses, likely to house sporting guns and sometimes militia equipment, might have offered richer pickings, but these seem to have attracted little more than threats, and on only one recorded occasion, on 14 June, Thomas Allen, steward at Longleat, reported to Lord Weymouth his fears of ‘a summons for horses and armes’, and that John Kidd, a former estate servant,Footnote 61 knowing ‘what armes were heretofore in the house … will break down your house to find them and may be fire it’. In the event Kidd stayed away and Longleat was spared the loss of the ‘13 case of pistols … 9 muskets, some old birding pieces, 36 pikes, 30 halberds, and 3 sutes of armor’ to be found there.Footnote 62

On 3 July, at Bridgwater, it seems Monmouth was offered (bizarrely, by none other than the brother of the Master Gunner of England) ‘a Machine, which would discharge many Barrels of Musquets at once … to be play’d at several Passes [ie in defence of the town] instead of Cannon’, that is, an ‘organ gun’, a row of musket barrels fixed to a frame and which could be fired almost simultaneously.Footnote 63 Monmouth refused the offer, but may yet have had one, if not used at Sedgemoor, as the Tower inventory of 1692–3 lists an ‘Engine of 12 Musq’t Barrells: taken from the late Duke of Monmouth’, valued at £3.Footnote 64

The fact remained, however, that Monmouth was woefully short of proper weapons. The rebel author of the ‘Anonymous Account’ of 1689, probably Colonel Venner,Footnote 65 lamented that the duke’s decision not to engage Albemarle and the Devon Militia on 14 June ‘in the end proved fatal to us, for had we but followed them we had had all their arms’, they would have driven all before them and been at Exeter in two days.Footnote 66 Andrew Paschall, the loyalist and politically minded rector of Chedzoy, observed that ‘on Sunday 21 June, he [Monmouth] marched into Bridgwater with about 5,000 men – armed about 4,000, unarmed about 1,000’.Footnote 67 It was observed of Monmouth’s troops by Sir Thomas Bridges on 28 June that of ‘his men some [were] well armed, others indifferent, some not at all, only having an old sword or a sticke in their hande’.Footnote 68 The ‘Anonymous Account’ also notes that on the approach to Bridgwater (21 June) ‘we were now between four and five thousand men, and had we not wanted arms could have made above ten thousand’;Footnote 69 on arrival at Frome on 28 June, ‘we wanted nothing but arms’,Footnote 70 but were disappointed that what might have been provided by the inhabitants had ‘by a curious stratagem’ been ‘taken from them a few days before our entrance’.Footnote 71 Then, in relation to the failure to take Bristol, the account notes that ‘For had we but had arms, I am persuaded we had by this time/ had at least twenty thousand men. And it would not then have been difficult for us to have march’d for London’.Footnote 72 In his deposition of July 1685, Richard Goodenough, Monmouth’s paymaster, similarly lamented that ‘If they had had 20,000 arms, they had had as many men, but brought onely 2500 arms’,Footnote 73 ruefully noting what they might otherwise have achieved. While his figures must be treated with caution, Taylor’s account of Monmouth’s forces on the eve of Sedgemoor tells us that Monmouth had, in addition to better-armed contingents and his ‘sithears’, ‘3000 foot more, some with Halberds, Prongs, bills & what they could gett’, and, in addition to ‘400 hors compleatly Armd’, about ‘300 hors more, which some had Arms & others none’.Footnote 74 Elsewhere, he describes the army as ‘badly armed’.Footnote 75 The need for improvised weapons was therefore obvious and urgent.

SCYTHES IN WARFARE

Scythes have been used in Britain since at least the first century ad,Footnote 76 and, until the late nineteenth century, were the principal tools for mowing hay, barley, rye and oats, and from the eighteenth century, for wheat.Footnote 77 Scythes are used two-handed, standing up, using a rhythmic swinging motion, the blade slicing through the crop near the ground: they should not be confused with sickles, also used for reaping but held in one hand while the other grasps the stems, and which have narrow crescent-shaped blades. Scythes in their intended form can, at a pinch, be used as deadly weapons, as allegedly in the martyrdom of the unfortunate Saints Sidwell, Urith and Walstan by pagan reapers, and whose symbol is a scythe.Footnote 78 At a more factual level, they are known to have been presented as weapons, if not necessarily wielded, in unplanned stand-offs between various authorities and rural labourers, not least by reapers actually at work: examples include those at Wolsingham (Co. Durham) in an incident related to enclosure in 1538,Footnote 79 and one at Holme Fen (Cambridgeshire) in 1632, related to drainage.Footnote 80 Such occasions cannot have been uncommon.

Unadapted scythes also appear in historic images of combat, such as that after Holbein of the German Peasants’ war (1524–5), Jacques Callot’s Les Misères et les Malheurs de la Guerre series of 1633Footnote 81 and even a contemporary depiction of Sedgemoor (fig 3), although the draughtsmen may not have realised that the blades were usually re-hafted;Footnote 82 at least one sixteenth-century author, Paulus Hector Mair, even produced instructions for their use in duelling, although whether actually practised is doubtful.Footnote 83 What may be an unadapted scythe is shown being used to cut a ship’s rigging in a fifteenth-century tapestry at Berne.Footnote 84

Fig 3. Scene from the woodcut illustration to a Broadside entitled ‘A Description of the late Rebellion in the West. A Heroick Poem’, published on 7 September 1685. The only contemporary image of the battle itself, it shows a scytheman, with a re-hafted scythe, among the rebels and an unconverted scythe discarded in the foreground. Image: from Anon 1685.

However, a working scythe, with the blade fixed to the haft or ‘snath’ at an acute angle, while capable of making martyrs, is a very clumsy weapon. On the other hand, re-fixing the blade axially to (that is, in line with) a straight haft makes a weapon to be reckoned with. In several European languages the result was dignified by its own term, reflecting their widespread use; hence, for example, Kriegsennse, Sturmsense, faux de guerre, falce di guerra, boiova kosa (Ukrainian), boevaja kosa (Russian) and bojowe kosa (Polish) – the English equivalent, ‘war scythe’, appeared only in the twentieth century, reflecting its relatively sparing use in the Anglo-Saxon world, and the term is more familiar to war-gaming enthusiasts than historians. Terms are important in identifying the use of re-hafted scythes in historical documents, but there are pitfalls: the French term fauchard or fauchon, for example, describing a variety of pole-arms with curved blades, is derived from faux, but only thanks to their loosely similar appearance, and not to the fauchard’s real form or origins. Terms clearly confused people even in the Middle Ages, including, it seems, the draughtsman of the English Assize of Arms of 1242 (discussed below).Footnote 85 The depiction of an unconverted scythe wielded by Perseus, in an early fifteenth-century illustration of Christine de Pisan’s L’Épître à Othéa of c 1400, probably owes to the artist’s interpretation of her word fauchon.Footnote 86 To complicate matters further, a variety of purpose-made pole-arms with curved blades also resemble the re-hafted scythe and have a cutting edge on the inner or ‘concave’ side of the blade: the most obvious is the glaive, with a straight-backed but curved-edged hafted blade of 2–3ft long, followed by the gisarme, with a rigid blade sharply curved towards the tip and spikes to the rear, and the many variants of the bill and the woodman’s slasher. Consequently, terms alone in the Middle Ages and later cannot be relied upon to differentiate re-hafted scythes from superficially similar but quite different weapons. Modern historians, unfamiliar with scythes, weapons or either, sometimes describe a variety of pole-arms shown in medieval and later images as scythes, as they are apt to do with sickles.

Scythe blades could also, incidentally, be used to make a form of sword by straightening the tang and fitting a hilt: an example, supposedly owned Thomas Müntzner, leader of the German peasants in 1525, is displayed in the Dresdner Rezidenzschloss; this is certainly a scythe blade with a straightened tang, although the eagle-headed brass hilt is seventeenth or eighteenth century and the object’s real history before the late nineteenth century is unknown.Footnote 87 The ‘Saxon’s sword’ at the Tower, described and illustrated in the 1780s and 1790s, may be another (fig 4).Footnote 88

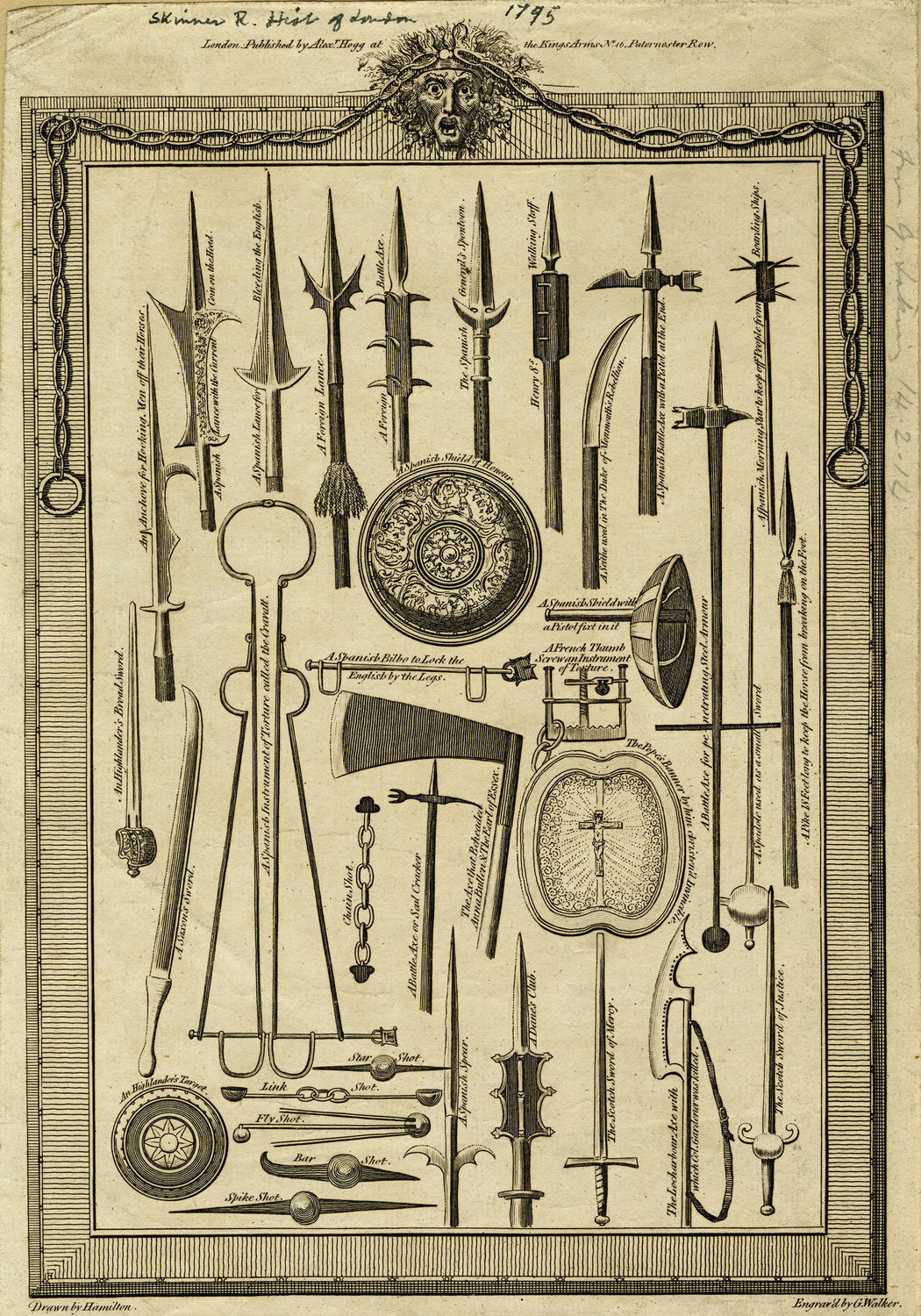

Fig 4. Engraving by John Hamilton (fl. 1766–87) of or shortly before 1784, reproduced in several topographical works in the late eighteenth century, showing ‘Various Weapons & Implements of War’ displayed at the Tower of London. A pole-hafted scythe blade, missing its heel (possibly vii.961) is shown (top right) captioned ‘A Scithe used in The Duke of Monmouth’s Rebellion’. The ‘Saxon’s Sword’ (lower left) is probably another scythe blade with a hilt fitted to its straightened tang. Image: © Royal Armouries.

Many agricultural, forestry and other tools can, of course, be used as or converted into weapons, notably the pitchfork and the threshing flail, both of which appear in descriptions and depictions of rebel actions from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, including in the contemporary woodcut of Sedgemoor (see fig 3); sickle blades could also be mounted on poles, if creating a weapon of dubious value. However, the abundance of scythes, used in both arable and pastoral farming, and the ease with which they could be converted prompted their particularly widespread use as weapons from the sixteenth century well into the twentieth. Although most commonly used by rebels and insurgents, they could also be issued to militia units or others attached to official forces: the municipal arsenals of Solothurn (Switzerland), for example, bought 475 Segessen (scythes) in 1499,Footnote 89 and the town council of Berne acquired large numbers in the seventeenth century;Footnote 90 the Royalist irregulars raised by Reverend James Wood against the rebels at Preston (1715), were ‘armed partly with swords and pistols and guns and partly with scythes fixed to the end of a long stick’,Footnote 91 and in 1720 or 1727 the garrison at Gibraltar was equipped with £10-worth of ‘upright scythes to defend the covered way or counterscarp’.Footnote 92 In 1848, contingents of the Hungarian militia were, according to their commander, ‘mostly armed with scythes’.Footnote 93 They were also used by Polish volunteer units raised by the regular army in 1939 (discussed below).

Surprisingly, however, while routinely mentioned in secondary sources and fiction relating to the Middle Ages, hard evidence of use before about 1500 has proved elusive.Footnote 94 Tantalisingly, the English Assize of Arms of 1242 contains a reference to the falces with which men with land and goods worth less than £2 were required to muster at the king’s request, along with gisarmes (gysarmas), knives and ‘other small arms’,Footnote 95 but the meaning is unclear: while falx was used in classical and medieval Latin to mean ‘scythe’, it referred also to other tools, and its use here may be intended to include any kind of pole-arm, improvised or otherwise. In fact, the earliest reference to (what were presumably) re-hafted scythes found in preparing this article, in either Britain or Europe, is that of 1499. This remains something of a puzzle, as, while scythes were less abundant before the Early Modern period, and would have been less effective against armoured soldiers than their cloth-clad successors, it is hard to believe that they were not used as weapons, for example (and as is routinely claimed in secondary literature) by the Hussites,Footnote 96 or in the Jacquerie of 1358, in 1381, by Cade, or in any of the hundreds of rural and provincial revolts of the period. Instances of earlier use will no doubt come to light.

As it stands, in a British context, the Sheffield ‘scythes which had a most Keene edge’, discovered with other arms in 1639 en route to the Scottish rebels, are the earliest known – although, as applicable to the reference of 1499, the inference is that these were weapons, or to be part of weapons, of an established type;Footnote 97 this is at least in keeping with a contemporary woodcut showing ‘Prentises and Sea-men’ assaulting Lambeth Palace in May 1640, in which the re-hafted scythe held by at least one of them passes without comment in the lengthy caption.Footnote 98 The next mentions relate to occasions in the Irish rebellion of 1641, one early in the yearFootnote 99 and another later, during both of which the protestant refugees in two castles in Co. Cavan (Ireland) successfully attacked their Irish besiegers with ‘scythes upon long poles’.Footnote 100 Instances followed in the English Civil Wars, including at Bradford in December 1642,Footnote 101 at CrowlandFootnote 102 and BirminghamFootnote 103 in 1643 and at Colchester in 1648,Footnote 104 and re-hafted scythes were also a favoured weapon of the civilian ‘clubmen’ who assembled to protect themselves and their property from both sides throughout the conflict.Footnote 105 Later, scythes were carried by the Covenanters at Rullion GreenFootnote 106 and in Galloway,Footnote 107 at DrumclogFootnote 108 and at Bothwell Bridge (both 1679);Footnote 109 the local antiquarian Ralph Thoresby noted that the ‘artificers’ of Leeds, fearing an imaginary Irish invasion, spent Sunday 16 December repairing firearms and ‘fixing scythes in shafts (desperate weapons) for such as had none’.Footnote 110 They were subsequently used by Jacobite troops before, at and after the Boyne (1690),Footnote 111 by both sides at Preston in 1715,Footnote 112 by loyalist irregulars mustered at NorthallertonFootnote 113 and in mob violence at Bromwich (Lancs) in the same year,Footnote 114 at Prestonpans in 1745,Footnote 115 and in Ireland again in 1760, at Carrickfergus,Footnote 116 in 1798Footnote 117 and in 1848.Footnote 118 No doubt the British Local Defence Volunteers of 1940 mustered a few as well.

On the Continent the deployment of such weapons was an all too normal practice for centuries, on the part of small bands and armies, in great campaigns and local revolts, and engagements from skirmishes to battles. Recorded sixteenth-century instances may be confined to the German Peasants’ War of 1525Footnote 119 and the revolt of the Pitauds (France, 1548),Footnote 120 but seventeenth-century ones are more numerous, including in the Austrian Jacquerie of 1624,Footnote 121 by the Ukrainians against the Poles at and after Berestechko in 1651,Footnote 122 by the Cossacks under Stepan Raziin in 1670–1,Footnote 123 and by the defenders of Mons in 1691.Footnote 124 Eighteenth-century instances (other than those in Poland) include those in Bavaria in 1705 (the Sendling massacre),Footnote 125 in the Pugachev rebellion of 1773–5,Footnote 126 in the Vendée in 1793,Footnote 127 and against the French near Berne in 1798 (Breitenfeld and Grauholz).Footnote 128 The next century saw them used in preparation for the landward defence of Copenhagen in 1801,Footnote 129 near Kassel (Hesse) in a rising against the French of 1809,Footnote 130 by the Prussian Landsturm (militia) in 1813,Footnote 131 in the Peninsular War,Footnote 132 in the Vendée again in 1832,Footnote 133 and in both HungaryFootnote 134 and Baden in 1848.Footnote 135 In 1837 a manual for the use of the Swiss militia was published in Chur (Graubünden), illustrating scythemen, in uniform and out, and describing their usefulness and deployment.Footnote 136 In the twentieth century – other than in Poland – they were used in the Spanish Civil War.Footnote 137

But it was the Poles who made the most widespread use of re-hafted scythes, most famously at the battle of Raclawice in 1794 and others of the same year,Footnote 138 and again in 1830,Footnote 139 1831,Footnote 140 1848,Footnote 141 and 1862–3 (the ‘January uprising’).Footnote 142 Twentieth-century use may have begun in 1908 in Austrian Poland, where both uniformed and peasant-clad nationalist volunteers were drilled in using the re-hafted scythe, and at least one illustrated manual was published, in 1913, to instruct them.Footnote 143 The weapons were used again in anger in the 1920s, but probably the final use of scythes in warfare on any scale, and perhaps the most heroic and forlorn of all, was in Eastern Pomerania in 1939: on 9 September, in a manner reminiscent of Monmouth’s action in 1685, the Polish commander in Gdynia ordered the re-quisition and conversion of 500 scythes, augmenting an existing force of scythemen that soon numbered as many as 2,000. By 20 September, having seen much action and some tactical successes, they, along with regular forces in the province, inevitably succumbed to overwhelming German strength.Footnote 144 A result of all this was that scythemen (kosynierzy) became symbols of Polish nationhood, abundantly represented in art and literature in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote 145 The most famous manifestation is the spectacular Panorama of Raclawice, painted for the centenary of the battle and now at Wrocław, which gives a convincing, moving and terrifying impression of scythemen in action (fig 5); the re-hafted weapon, or at least the blade, appears on numerous nationalist emblems from the late nineteenth century onwards,Footnote 146 and the crossed blades, along with a scytheman’s cap, featured on the insignia of the 7th Kościusko air squadron, formed in 1919,Footnote 147 and that of the RAF-equipped Dywizjon Myśliwski ‘Warszawski im. Tadeusza Kościuszki’ (‘The Tadeusz Kościuszko Warsaw Fighter Squadron’) of 1939.Footnote 148

Fig 5. Detail from the Panorama racławicka (the Raclawice Panorama), painted in 1894 by Jan Styka and Wojciech Kossak, now at Wrocław. It shows the moment, in the battle of April 1794, when Taddeusz Kościuszko’s kosynierzy overran the Russian battery. Scythes had been used in Poland within the lifetime of the artists, as they would be later, so we can be confident that this is a realistic depiction of scythes in action. The Russian flintlock small arms and artillery of 1794 had changed little since Sedgemoor. Image: A fragment of the Raclawice Panorama, Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Re-hafted scythes were also, not surprisingly, used in areas where the original implement was employed outside Europe, including in North America and India: in the former, examples include the Mormon defence of Fort Limhi (present day Idaho) in 1858;Footnote 149 and in the latter, use by civil rebels in the Mutiny.Footnote 150

Surviving ‘war scythes’ in the British Isles may be confined to the Royal Armouries’ examples and twelve of the thirteen blades displayed, quite remarkably, in St Mary’s church Horncastle (Lincolnshire) (fig 6), nine with tangs straightened for fitting into the haft-end, two with tangs bent round to form sockets, and one flattened and pierced with three holes for rivets (fig 7). All twelve are thin-bladed, ground on the underside and have raised ridges at the rear, as with (bar the grinding) vii.960 and vii.961, although whether steel-edged or wholly of wrought iron is unclear. The blades are the survivors of up to fifty displayed there, ‘many’ still hafted, until 1861, and have a traditional and part-recorded history of great interest.Footnote 151 A scythe blade with a straightened tang at Snowshill Manor (Gloucestershire), in the former collection of Charles Paget Wade (d. 1956), may be another, although the wear pattern suggests it may have been adapted for use in an improvised chaff-cutter, or at least re-used as such.Footnote 152 As for those abroad, the Metropolitan Museum of Art formerly had two,Footnote 153 and the Philadelphia Museum of Art at least one,Footnote 154 but most, amounting to many hundreds, survive, needless to say, in Europe and include: in France, two held by the Musée de l’Armée,Footnote 155 and a possible example in the Musée de l’art et d’Histoire at Cholet (Maine-et-Loire);Footnote 156 in Germany, examples are to be found in the Deutsches Historisches Museum in BerlinFootnote 157 and the Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr in Dresden;Footnote 158 in Switzerland, they are to be found in the Bernisches Historisches MuseumFootnote 159 and at least one municipal building in Berne,Footnote 160 the Museum Altes Seughaus in Solothurn,Footnote 161 the Landesmuseum in Zürich,Footnote 162 and the Schloss Kyburg near Zürich;Footnote 163 in Poland at the Wawel in Krakov,Footnote 164 the National Museum Krakov (Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie),Footnote 165 and the Polish Army Museum (Muzeum Wojska Polskiego) in Warsaw.Footnote 166 Other owners include the National Museum (Nacionalinis Muziejus) in Vilnius,Footnote 167 the Zaporozhye Museum of History in Zaporyzhia (Ukraine)Footnote 168 and the Salzburg Museum.Footnote 169 Further specimens no doubt survive in public ownership, and clearly do in private hands, as shown by their occasional appearance at auction.Footnote 170

Fig 6. The thirteen blades displayed in St Mary’s church, Horncastle (Lincolnshire), all but one of which were hand-made and adapted for service as weapons. At least fifty were present in 1861. When and why they were adapted and placed here remains to be discovered. Photograph: John Aron.

Fig 7. Details of two Horncastle blades showing the two forms of adaptation: in (a) the tang has been straightened to fit a drilled hole in the end of the haft, as in vii.960; in (b) the tang has been bent to form a socket through which the haft was passed and then riveted to the blade. Photographs: John Aron.

The effectiveness of ‘war scythes’ is most obviously indicated by their widespread and enduring use, but is also illustrated by specific instances and recorded details. Among these is the gruesome death of a tax official in the Pitaud revolt, decapitated by a ‘Faux emmanchée à l’envers’,Footnote 171 and during the Irish rebellion of 1641 mentioned above, when the Irish ‘made such foul work and havoc amongst their enemies that such persons as were not cut to pieces, or mangled with these terrible weapons, were either taken prisoners or forced to run away’.Footnote 172 Taylor, although not at Sedgemoor,Footnote 173 but who can be assumed to have visited the battlefield on 6 or 7 July and spoken to survivors,Footnote 174 tells us that:

for indeed these Sithes was a desperat Wepon, loping off at one Stroak, either head, or Arm, and I saw a man layinge among the dead, whose back was clove down, by one struck of these Sithes, and a horse whose head at one strock, was almost separated from his body.Footnote 175

In a marginal note he adds that ‘now that their orders was to cutt of the bridle arm, thereby the disable the riders, and defend themselfs, the which they to the last stoutely did’.Footnote 176 An eye-witness at Prestonpans observed similar effects: ‘The MacGregor company with their pikes [re-hafted scythe blades] made most dreadful carnage’ and ‘cut in two the legs of horses, as well as the horsemen through the middle of the body’.Footnote 177 In the Vendée revolt of 1793, Louis Brard, a participant in an engagement at Vrines (Poitou-Charentes), reported that the survivors of a scythe assault ‘were missing limbs, had horrible gashes, with shreds of flesh falling from their bodies’.Footnote 178

At Raclawice, Kościusko’s own account of the battle explains that the Russian battery had time to fire only two rounds before ‘together [our] pikes, scythes and bayonets broke the infantry, overcame the cannons and took apart the column in such a way that the enemy cast aside his weapon and ammunition pouch as he fled’ (see fig 5).Footnote 179 Aigner (see below), while himself not a front line combatant, asks in his Manual, ‘who will not admit that scythes are a terrifying weapon in the hand of our Peasants fighting for property, liberty?’ He further explains that:

The scythe terrifies the horse with its brightness, and thereby slows the momentum of the cavalry; it puts to the cavalryman a weapon more terrifying than a sword and inflicts mortal blows upon him. This I have from mouths worthy of belief, as in the camp of the commander-in-chief of the armed force are found peasants who so nimbly and swiftly put scythes to the cossacks that their heads flew off in the blink of an eye.Footnote 180

A report of Lublin in 1863 similarly observes that, cornered by the Russian cavalry,

Some of the insurgents tried to defend themselves; and, with sharp scythes which were their chief weapons, inflicted frightful gashes upon the men and horses … Many of the mangled horses were to be seen, having lost their riders, galloping about with their entrails hanging out.Footnote 181

This account is a reminder of the effectiveness of scythemen, in particular, against cavalry, horses’ bellies and sinews being very vulnerable to their long sharp blades; hints that this was well understood are to be found in a number of sources, including in the incidents at Bradford in 1642 (mentioned above), where Sir John Gothericke ‘had his horse killed with a syth’,Footnote 182 ‘our sythes and clubs now and then reaching them, and none else did they aime at’Footnote 183 and when the Parliamentarian musketeers fired on their counterparts, the scythemen ‘fell upon their horse’, the aim being their ‘scattering’.Footnote 184

Their actual effect could be enhanced by their psychological impact, not least on professional soldiers confronting a weapon of unknown capability and against which no drill had been devised, possibly heightened by the image of the scythe-bearing ‘Grim Reaper’, of biblical origin, depicted in increasingly familiar form since the fourteenth century.Footnote 185 As noted at Colchester in 1648, the ‘sythes, straightened and fastened to handles, about six foote long’ were ‘weapons which the enemie strongly apprehended, but rather of terror than use’.Footnote 186 In a similar vein, Monmouth’s ‘sithes’ were indignantly described by the Royalist drummer Adam Wheeler as ‘cruell and new invented murthering weapons’,Footnote 187 and by Taylor as ‘Strang and Unheard of’.Footnote 188 John Oldmixon, a twelve-year-old witness to the battle, was convinced of both their practical and psychological effect: had Monmouth’s battle plan succeeded, he later wrote, ‘the soldiers … asleep in their Tents … might have been cut to pieces by the Scythemen, of which the Duke had 500, [and] the Terror of the Weapon unleashed on the sleeping royal army [would have] added to the Slaughter and Horror of the Night’ and ‘given the rest of the Duke’s forces an easy Victory’.Footnote 189 In a similar vein, in 1793 it was noted that Vendéens, attacking a battery, ‘avec leurs faux et leurs fourches … écharpaient les artilleurs frappé de stupeur,’Footnote 190 while another contemporary, noting the peasants’ use of ‘faulx emanchées à l’envers’, added that they were ‘weapons of terrible appearance’.Footnote 191 The point is well reinforced by the German troops’ disproportionate fear of the Gdynia scythemen, whom they called ‘die schwarze Teufels’ (‘the black devils’), and later made the victims of vicious retribution.Footnote 192

To this it might be added that the potential military usefulness of scythes, both pre- and post-conversion, could be recognised and feared by officialdom. In Austria, during the Peasants War of 1620–5, smiths detected converting agricultural implements into weapons – if not exclusively scythes – were punished with death;Footnote 193 and a similar order was issued by the English Commissioners for Ireland in 1651.Footnote 194 In Poland in 1863, under Russian occupation, a printed certificate signed by the Chief of Police was required ‘to acquire for farming purposes [number] of scythes’, clearly to restrict their use as weapons.Footnote 195

To test and add to historical evidence of the effectiveness of the ‘war scythe’, in 2018 the author had the tang of a haft-less blade straightened by the Otley blacksmith Joseph Pack, and fitted it to an 8ft hazel haft, reinforced at the sharp end by two iron collars, and then honed it to a carving-knife sharpness.Footnote 196 The blade is a twentieth-century example of the ‘Austrian’ type, a little shorter, thicker and heavier than Monmouth’s scythes and which therefore handles differently but makes a weapon close enough in type for some useful experiment. The effect on a suspended (roadkill) roebuck carcass, showed, in short, that eye-witness accounts of dismemberment and evisceration are all too plausible.Footnote 197

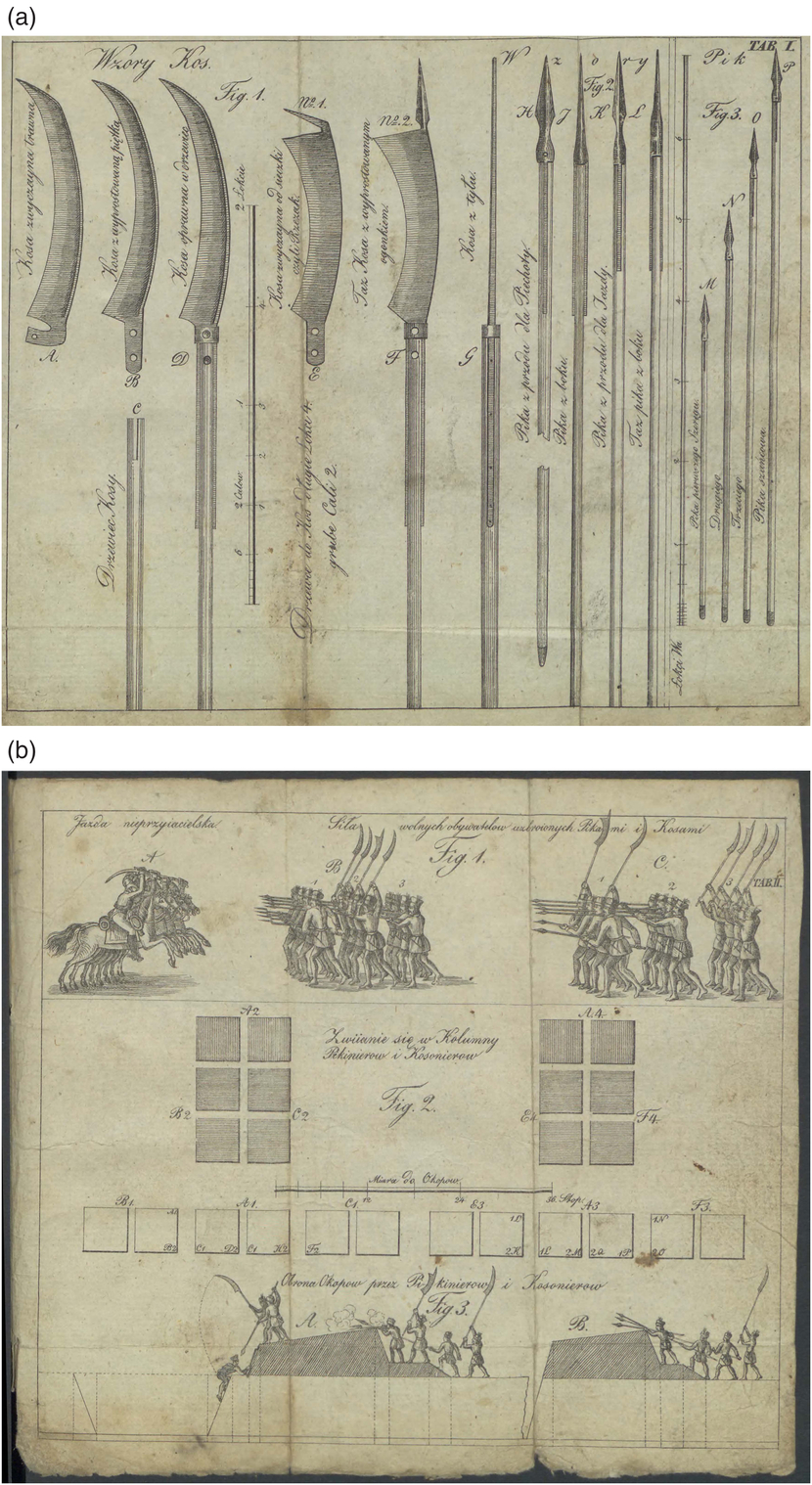

The fact was, however, that re-hafted scythes as a battlefield weapon bore no comparison in overall effectiveness to purpose-made equipment, particularly to firearms and pikes in trained hands or to disciplined and determined cavalry. Fighting a live and retaliating opponent would have been more testing, not least in that a freshly cut haft, especially in summer – a far cry from the professionally made pikestaff of seasoned ash with langetsFootnote 198 – could have been severed by a powerful sword stroke, which may explain the apparently short-handled weapons shown on the contemporary playing cards (see fig 10). In addition, rapid shrinkage of green hafts would have required repeated adjustments to the fit of blade, or soaking in water – even, in the case of Monmouth’s rebels, between 31 June and 6 July. Scythemen, therefore, tipped the scales of victory in few major battles involving regular or official forces – Raclawice being the most obvious example – although their role in skirmishes and actions could be tactically important, as, for example, at Prestonpans, Lublin, and even in Gdynia in 1939. This was recognised by Kościusko himself who wrote that ‘The strength of Pikers and Scythers cannot withstand regular armies’, although his remedy was that ‘they are themselves incorporated into regular armies’, suggesting that the issue was more with training than the weapon.Footnote 199 To this effect, he commissioned the Warsaw architect Chrystian Piotre Aigner (1756–1841) to write his remarkable Krótką naukę o pikach i kosach (A Short Treatise on Pikes and Scythes) of 1794, setting out how both could be used to best effect (fig 8).Footnote 200

Fig 8. Two diagrams from Krótką naukę o pikach i kosach [A Short Treatise on Pikes and Scythes]showing: (a) how blades, both ‘mowing scythes’ and chaff-cutting blades, could be adapted and re-hafted; and (b) how a ‘force of free citizens’ armed with pikes and scythes might be deployed in the field. Images: From Aigner Reference Aigner1794, Tablica i and Tablica ii.

PROCUREMENT AND CONVERSION

Monmouth’s men garnered these weapons by a variety of means. Some must have been brought in by the rebels, newly made for the occasion or as relics of the Civil War; some of the 160 members of a ‘Club army’ who joined Monmouth’s army encamped near Bridgwater on 2 July may have inherited such things;Footnote 201 Thomas Allen reported that when John Kidd and the cloth worker Weely marched out of Frome on 4 July, ‘their armes were Hatchets, Clubs, Hayforks and Sythes riveted into poles about 8 foot long’.Footnote 202 As these sources, TaylorFootnote 203 and others show, scythes were not the only tools pressed into or adapted for service by Monmouth’s forces, but Monmouth’s order to requisition them, within a week of landing, shows that they were the weapon of choice: presumably the duke was impressed by those his men already had, but may also have recalled their use against him at Bothwell Bridge in 1679.Footnote 204 Accordingly, on Friday 19 June, as noted in a postscript to an anonymous account of the rebellion, there:

were issued out warrants and subscribed Mon; requiring all Constables in their respective hundreds & tythings, to bring into the camp at Taun[ton] by Saturday mor: 10 of the clock all sythes; of those warrants I sawe one, and read it at Kingstone.Footnote 205

The text of one of the warrants was transcribed by Paschall, headed ‘a copy of the warrant for scythes’ and is addressed in this case ‘To the Tithing-men of Ch.’. It states that:

These are, in his Majesty’s name, to will and require you, on sight hereof, to search for, seize, and take all such scythes as can be found in your tything, paying a reasonable price for the same, and bring them to my house tomorrow by one of the clock in the afternoon, that they may be delivered in to the commission officers, that are appointed to receive them at Taunton by four of the same day, and you shall be reimbursed by me /what the scythes are worth. And hereof fail not, as you will answer to the contrary. Given under my hand this 20th day of June, in the first year of his Majesty’s reign.Footnote 206

The text was published by the lawyer, historian and would-be biographer of Monmouth, Samuel Heywood (1753–1828) in 1811.Footnote 207 The ‘Tything-men’ were parishioners responsible for public order, usually subordinate to elected constables; Monmouth’s claim to authority was, only hours old, as ‘king’, hence the threat to the tything-men of having to ‘answer’, and, according to George Roberts, writing in the 1840s, of ‘having their houses burnt’.Footnote 208 The ten-mile distance between Chedzoy and Taunton suggests that the warrants were issued to a number of places within at least that radius, and they were perhaps printed; the example seen by Heywood may been preserved by Paschall. How many blades were ‘delivered in’ is unknown, but the strength of scythemen by the end of the campaign, at about 500, suggests some success; a ‘reasonable price’, meanwhile, would have been between one and two shillings apiece.Footnote 209 The ‘house’ in Taunton was presumably ‘Mr Hookers’, described by Wade as the ‘Duke’s quarters in this town’.Footnote 210

What is obvious, however, is that there would have been little time after issuing the order on Saturday 30 July and 4 o’clock the next day to cut and prepare enough hafts, preferably ash or, at a pinch, of hazel, willow or birch. Taylor noted, as observed after the battle, that the hafts he saw were ‘Strong Stafs about ten feet long, of good supple Ash, about 1½ Inch Diameter’.Footnote 211 There was still less time, between 4 o’clock and the army’s departure for Bridgwater on the same day, to adapt the blades, even though a smith working in a forge would have needed no more than five to ten minutes’ work per item,Footnote 212 and a few minutes to prepare at least one iron ring or ferrule to keep the haft from splitting.Footnote 213 Using the simplest process, as in the case of vii.960, the next stages were to shape the shaft to take the rings and then drill and shape a socket to fit the tang, tasks that took the author (in making the replica ‘war scythe’ discussed above) four to five minutes and about thirty-five minutes respectively.Footnote 214 Fitting the blade and driving it home was the work of a few seconds, so, using this method, the whole process (apart from procuring the haft) of creating the weapon would have taken roughly an hour; the other methods described below, which may also have been used, could have taken a little less. The result was illustrated (fig 9) and described by Taylor: ‘these Sithes were about fower foot Long, and fower inches brod, and one Inch thick at the back’, and he added that ‘in the Lowerward they were bound with a ferul [ferrule] and had a sharp spike, about 9 inches long, in all respects as you see in the figure’,Footnote 215 a refinement that was perhaps a rarity. Taylor also relates that the ‘sithers’ had ‘pistols sticking in at their Girdles, and brod sords, in wast belts’, but this is unlikely to have applied to many, any more than the plumed and lace-bedecked costume portrayed in his drawing.

Fig 9. Drawing c 1688–9 by John Taylor from his ‘Historie of his life and travels in America and other parts of the universe’. Taylor had joined the royal army as a Royalist cadet and, although not present at the battle of Sedgemoor, had visited the site immediately afterwards. He misunderstood how the blades were re-hafted, and the dandified costume cannot have been typical, but this remains the only detailed near-contemporary depiction of a Monmouth scytheman. Image: Courtesy of the National Library of Jamaica (ms 105).

Creating these weapons in a hurry, of course, depended on the availability of smiths and forges, although at a pinch it could have been done without specialist equipment by any practical man. Monmouth’s ranks, as any army’s had to, certainly included smiths and farriers, such as James Edwards of Shepton MalletFootnote 216 and Daniel Manning, apprentice to Walter Upham, who was conscripted at Shoreditch (near Taunton).Footnote 217 There must also have been smiths in Taunton, perhaps including Messrs Caninges, Ayles and Case, mentioned respectively in 1656, 1663 and 1672,Footnote 218 and the blacksmith Dyer, who came to Monmouth at or on the way to Bridgwater with a copy of the king’s pardon and was promptly arrested.Footnote 219 There were, of course, others in nearby villages (three named in 1680 and 1684)Footnote 220 whose services may have been offered or commandeered, as in the case of labourers summoned to Bridgwater on 2 July.Footnote 221

The conversion method found in vii.960 is common to the majority of surviving continental examples, including most of the thirty-seven at Solothurn,Footnote 222 but a still simpler method, at least as illustrated in nineteenth-century images of historic actions and illustrated in detail in the Polish Regulamin Ćwiczeń Kosą of 1913, was to use two rings to fix the tang to the side of the pole’s end;Footnote 223 this also seems to have been used by the Vendéens in 1793.Footnote 224 Other simple processes were employed, depending on choice and the form of the tang as found. In the case of a broad, flat tang, it could be inserted into a sawn slit at the end of the haft and secured by rivets, as illustrated by Aigner in 1794, langets also being fitted (see fig 8a).Footnote 225 A third method, used in the case of two of the Horncastle blades, several in the Polish Army Museum, one at Berne, and by the Vendéens,Footnote 226 was to re-form the tang into a ring, through which six inches or so of the pole could pass and then be riveted to the blade (see fig 7b).Footnote 227 The fixing method found in the other RA example, vii.961, would only have been required if, as in this case, the tang was missing, although here the arrangement probably post-dates its arrival at the Tower, as does the haft.

More sophisticated weapons could be made, time and skill permitting, by adapting the blades themselves; as in the early seventeenth-century examples at the Schloss Kyburg, in which they have been re-ground to present a convex edge and a point, and riveted to a square-sectioned or octagonal haft with the aid of long metal strips.Footnote 228 A variant of this, found in an eighteenth-century Polish example, was to straighten the blade itself and point the end.Footnote 229 An eighteenth-century exhibit in the National Museum Krakov, has a straightforward socketed tang, but with the addition not only of langets (fitted under the collar), but also a backward-facing hook, secured by two rivets, for dismounting horsemen.Footnote 230 On the Continent, similar weapons, most commonly in Poland, were made using blades taken from chaff-cutters, broader at the far end and terminating in the spike on which the blade pivoted when in use.Footnote 231 These seem not to have been used in the British Isles, probably as these devices were rarely used here before c 1800.Footnote 232

DEPLOYMENT AND EFFECTIVENESS IN 1685

Scythemen first appear in the contemporary accounts of the rebellion in relation to ‘Capt. Slape’s company of sithes and musquetes being 100’ added to the duke’s forces on 21 June, nine days after landing.Footnote 233 Their first action appears to have been in the encounter at Norton St Philip (27 June), where Wade, anticipating renewed attack by Feversham, ‘drew up 2 pieces of canon into the mouth of the lane and guarded them with a company of sithmen’.Footnote 234 The enemy withdrew, but to be noted is that the scythemen’s anticipated role was wholly defensive, that is, to protect the guns and gunners. Scythemen saw action again the next day at Frome, where, the London Gazette reported, recruits (said to have been 2,000–3,000 strong) armed ‘some with Pistols, some with Pikes and some with Pitch-Forks and Sythes’Footnote 235 engaged a militia force under the Earl of Pembroke. Wheeler tells us that the earl ‘forced the Rebells to lay downe theire arms’, including ‘Sithes and the like’.Footnote 236

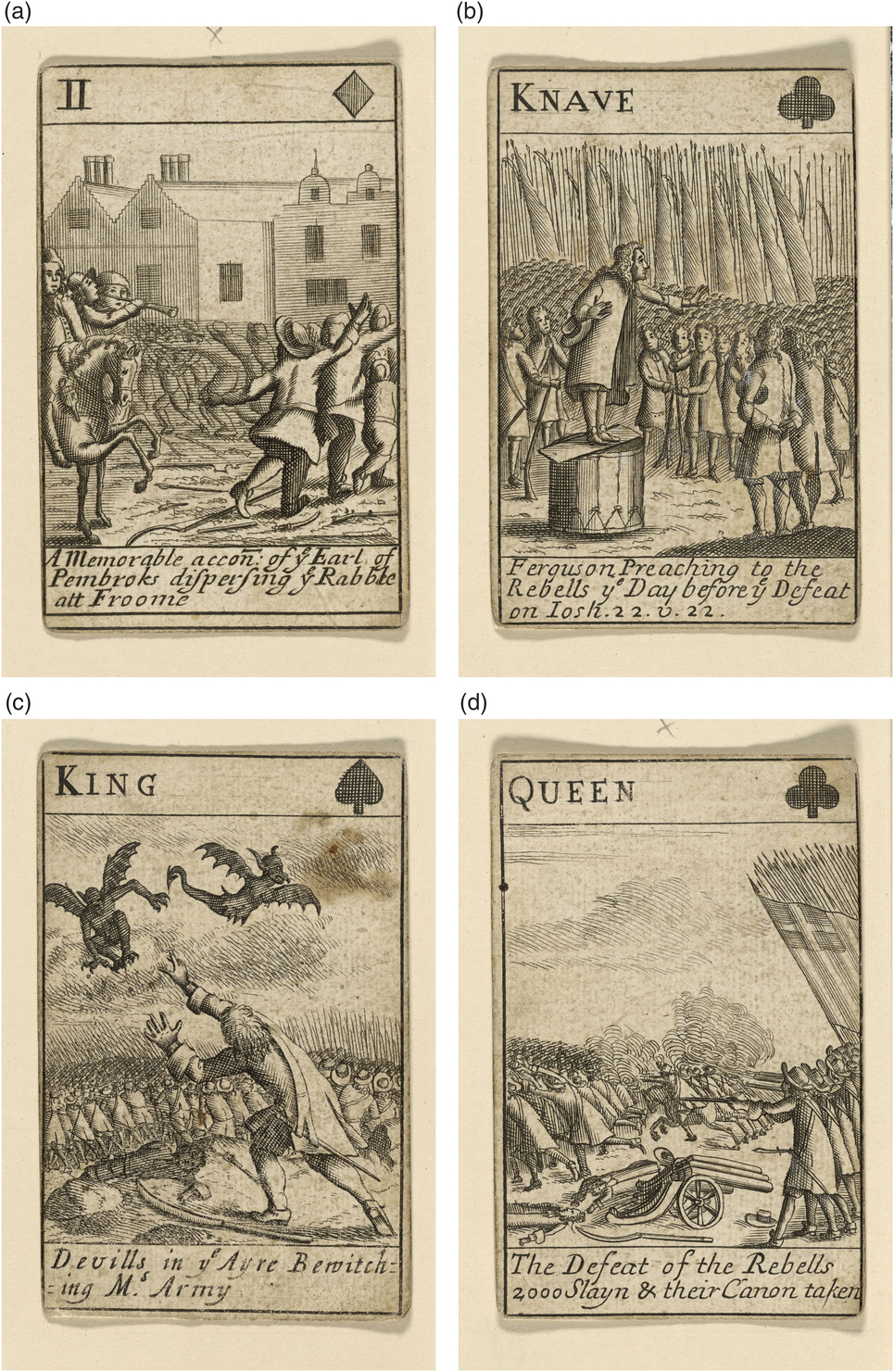

The next engagement involving scythemen seems to have been Sedgemoor itself. Their numbers, deployment and command are not wholly clear, but a key source relating to both issues is James ii’s own account. This explains that on the final approach to Sedgemoor were ‘the Foott, which consisted of five great Battalions, each of wich had one company of at least 100 Sythmen instead of Granadeers’;Footnote 237 the ‘Battalions’, as Wade reported, were the Blue, White, Red, Green and Yellow regiments of infantry, in addition to which there was an eighty-strong ‘Independent Company which came from Lime’.Footnote 238 King James’s report therefore implies a total of about 500 scythemen (a figure also cited by John Oldmixon)Footnote 239 and that they were under the command of various regimental colonels. Taylor, meanwhile, although not a reliable source for rebel numbers, wrote that ‘Munmouth had in his Army 300 sithers’.Footnote 240 Confusingly, however, Paschall’s (longer) account refers to ‘1000 scythe-men’,Footnote 241 but he was not present at the battle, unlike Wade, the king’s primary source. The king’s explanation that scythemen were used ‘instead of Granadiers’, while surprising in that they had neither the equipment nor training of these elite troops,Footnote 242 concurs with Taylor’s comment that ‘these sithemen were the Tallest and lustyest men they could prick out’.Footnote 243 Both statements tend to underline the importance that Monmouth attached to these men and their weapons, and King James’s is also interesting in hinting that – as was the case with grenadiers – the ‘sithemen’ were dispersed among the ranks of musketeers and pikemen, as does the reference to Slape’s ‘company of sithes and musquetes’. Scythemen are also shown mixed among pikemen on one of a remarkable set of contemporary playing cards (fig 10),Footnote 244 although not actually at the battle, and in a woodcut illustrating a Broadside of 7 September 1685 (see fig 3).Footnote 245

Fig 10. Four playing cards from a commemorative pack of 1685, illustrating incidents in Monmouth’s rebellion. (a) The two of Diamonds shows a re-hafted scythe on the ground at Frome, (b) the Knave of Clubs shows re-hafted scythes interspersed with pikemen, and (c) the King of Spades and (d) the Queen of Clubs show other scythes abandoned at Sedgemoor. Images: Reproduced by kind permission of the British Museum, © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Other sources, however, suggest that scythemen instead formed a discrete unit (or units). One of these is the confession of John Kidd, which referred to one William Thompson, ‘an officer and linnen draper of London’ who ‘commanded the Scythemen’;Footnote 246 another, varying the theme, is Taylor, who tells us that on the morning of Sedgemoor

Munmouth ranged both his horse, and foot forces, and put them in order; Himself; and Count Horn, commanded the Infantry; Count Horn commanded the Sithmen particular, and the Left Wing; Munmouth commanded his maine Batatalia of Foot, and the Lord Greay, commanded the Body of the Calvary.Footnote 247

By ‘Count Horn’, Taylor is referring, as Childs has shown, to the mercenary Anthony van Buys, who had landed with the duke, and eventually turned king’s evidence and was pardoned.Footnote 248 Prior to the battle, the scythemen had been formed into a discrete detachment under Captain James Hayes of the Red or Duke’s regiment, which we can assume (if these sources are correct) was in the end led by van Buys.Footnote 249 This is consistent with Taylor’s claim that after Grey had fled ‘Count Horn and his Sithears stoutly maintained their ground against Oglethorps hors … until Mounmouth’s Main Batallia drew up’.Footnote 250 King James’s account is similar in mentioning that Oglethorpe’s cavalry ‘tryd one of their Battallions, but was beaten back by them, tho they were mingled amongst them, and had severall of his men wounded and knocked off their horses’.Footnote 251

Taylor’s comments at this point and elsewhere on the role of scythemen in the battle are also useful in refuting Paschall’s claim that scythemen were wholly absent, to the effect that Wade’s 1,000 ‘scythe-men’ were among those who ‘came not to the fight’.Footnote 252 Clearly they were not, and, as Taylor reveals in describing their effect, they left a lasting impression on observers. It is also significant that re-hafted scythes are shown, respectively, discarded and in use on the battlefield on the playing cards and the Broadside of September 1685 (see figs 7 and 8).

MONMOUTH’S SCYTHES AT THE TOWER OF LONDON

Sedgemoor ended, as Paschall put it, with a ‘total rout of the Duke’s army’.Footnote 253 In addition to 200–400 rebels killed in battle, many more were cut down in fleeing: the parson and churchwardens of Westonzoyland counted 1,384 burials within the parish, and the bodies of others, who died in the cornfields, were only found at harvest.Footnote 254 Their arms were abandoned in flight or left where they fell: the Earl of Pembroke, although not an eye-witness, wrote of ‘the rout of Sedgemore, where most of them were killed, droping their armes and flying into ditches’.Footnote 255 Taylor tells us that the rebels ‘in the most confused maner betoock themselves to flight, each shifting for himself as well as he could soe that nothing but Scaterd Arms, and dead carcasses lay every where, scattered on the Ground’.Footnote 256 The arms must have included re-hafted scythes, and indeed both the King of Spades and the Queen of Clubs in the ‘new pack of cards representing (in curious lively Figures) the Two late Rebellions throughout the whole course hereof in both Kingdoms’, printed in November 1685, show them lying on the ground,Footnote 257 as does the only other contemporary image of the battle, the Broadside of September 1685 (see fig 8).Footnote 258 The scene must have resembled that in the colourful and ghastly painting of the massacre of a peasant army in 1705 at Sendling, near Munich, which shows dozens of re-hafted scythes and other tools scattered among the casualties.Footnote 259

Normal seventeenth-century practice for the victors, followed by swarms of camp followers, was to seize anything useful or valuable from the dead, wounded and captured, although the speed of the Sedgemoor campaign meant followers were few.Footnote 260 At Sedgemoor, the eagerness of government troops to begin is evident from Adam Wheeler’s account, in which he ‘was one of those/of the Right Wing of his honour the Colonel Windham’s Regimt who after the Enemy began to run desired leave of his honour to get such pillage on the feild as they could finde’, although Feversham’s answer was at that moment no, ‘on Paine of Death’.Footnote 261 This ‘pillage’ involved the robbing of any prisoners who, as Wheeler put it, ‘had a good Coate or any thinge worth the pilling’ and ‘were very fairely stript of it’.Footnote 262 The retrieval of weapons, however, was a matter of official interest, thanks to their value both to the victors and potentially to enemy survivors. On their destination, Taylor is helpfully specific: following his description of their effectiveness, he adds that ‘These Sithes with abundance more of Mounmouth’s other Arms were brought Up to London, and laid up in the Armory of the Tower of London’.Footnote 263 The ‘other arms’ may have included at least some of the armour taken at Lyme and sold from the Tower in 1717, and presumably also Monmouth’s cannon, a supposition supported in the mention by an eighteenth-century Tower visitor Georges-Louis Le Rouge, of ‘quelques armes & pieces de canon prises sur le Duc de Mont-Mouth’ in the Spanish Armoury.Footnote 264 Other items were also captured before the battle: the scythes ‘brought away’ by the Earl of Pembroke after his encounter with the rebels on 25 June at Frome;Footnote 265 the powder and armour captured at Lyme on 30 June;Footnote 266 and perhaps the ‘Engine’ recorded in 1692–3.Footnote 267

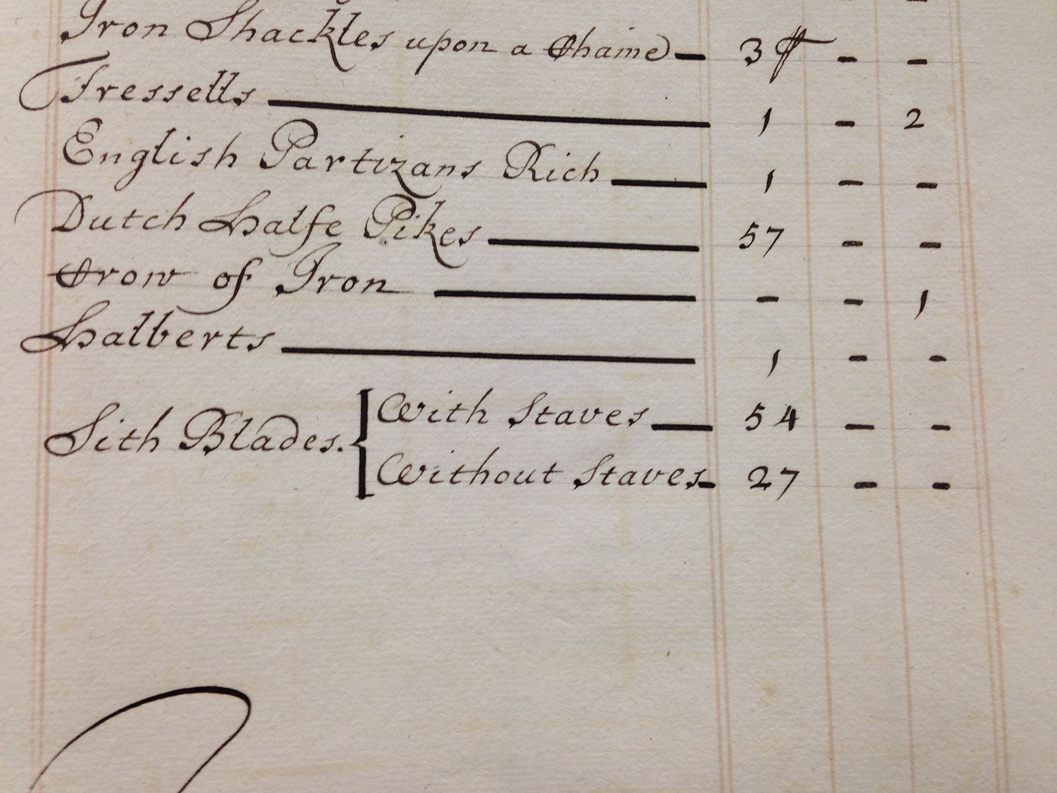

Re-hafted scythes first appear in the Tower records in the ‘Survey and Remaine’ finished on the 17 September 1686, described as ‘Scith blades: with staves, 54; without staves, 27’, all in the ‘Serviceable’ column and listed under ‘Spanish Weapons’ (fig 11);Footnote 268 in 1687 there were ‘95’ ‘sithes’ and ‘27’ ‘sithe blades’ (although ‘95’ may have been a clerical error for ‘54’), all ‘serviceable’ and valued respectively at £25 17s and £6 1s 6d.Footnote 269 Should there be any suspicion that these were not weapons but tools for foraging, those appear in quite separate lists, and had been kept there in large numbers since at least the reign of Henry viii:Footnote 270 the inventory of January 1692/3 lists under ‘Sundry Stores and Incident Necessary’, ‘Sneaths for Sithes, 118’, valued at £1 9s 6d;Footnote 271 the 1713 ‘Remaine’ lists under ‘Tooles of sorts’, including sickles and axes, ‘Scyth Blades, 34; ditto handles, 394; Rings for Scyths, 382, Iron Wedges for Ditto, 870; Wooden wedges, 800’.Footnote 272 The scythes mentioned were therefore quite clearly weapons, while their listing in 1686 and thereafter under ‘Spanish Weapons’ implies that they were displayed in the ‘Spanish Armoury’, which, along with the Line of Kings and (after 1688) the Small Armoury, was one of the three main attractions at the Tower created after the Restoration.Footnote 273 Its main contents were, it was claimed, taken from the Armada of 1588, and by 1676 had been assembled in the ‘Spanish Weopen House’, a building near St Peter’s chapel, before being re-displayed in 1688 on the middle floor room in a storehouse in ‘Coldharbour’, the inmost ward, to the south of the White Tower.Footnote 274 The scythes’ Monmouth associations were certainly being given out from 1693, probably by Yeoman Warder guides, when they were viewed by the Lutheran Pastor Heinrich Benthem. In his Engeländischer Kirch-und Schulen-Staat of 1694 he noted that ‘here some scythes (sensen) can be seen with which a whole regiment of Monmouth’s army was equipped/ and at the beginning caused considerable damage/ as their blood was then still up’.Footnote 275 The main purpose of the display, largely of material allegedly intended to defeat, torture and oppress the vanquished English,Footnote 276 was to trumpet England’s invincibility and the perfidy of her enemies. Unlike the Line of Kings or the Small Armoury, however, the Spanish Armoury was effectively also a ‘cabinet of curiosities’, a type of attraction long familiar to Londoners and their visitors, such as John Tradescant’s ‘Ark’ at Lambeth (extant 1628–83), Robert Hubert’s ‘natural rarities’ near St Paul’s (1660s),Footnote 277 the East India Company’s, the Royal Society’s (1666 onwards) and the London College of Physicians’ (1654–66).Footnote 278 The scythes were therefore not alone in lacking even an alleged ‘Spanish’ provenance, being accompanied in 1687 by (for example) four ‘Danish clubs’, ten ‘Hercules clubs’, ‘Heading axes, 1’, ‘King Henry ye 8’s walking staffe’ and a shield ‘of wood with pistols’, value £1.Footnote 279

Fig 11. Extract from the ‘Survey and Remaine’ of 17 September 1686, showing the entry under ‘Spanish Weapons’, that is, those displayed in the so-called ‘Spanish Armoury’, naming the ‘Sith Blades’, fifty-four of them with staves and twenty-seven without (TNA: PRO, WO 55/1730, fol 14r). Photograph: Reproduced by kind permission of The National Archives; © Crown copyright.

During the short remainder of James’ reign, in line with the government’s intentions to discredit Monmouth’s cause,Footnote 280 exposing the scythes to the public conveyed a fairly straightforward warning against rebellion, although their makeshift nature would hardly have trumpeted the prowess of the victors. Under William iii, however, who had successfully pursued a version of Monmouth’s plan,Footnote 281 their display risked being seriously off-message, as apparently noted by the Tower authorities, as the ‘Spanish Weapons’ in the inventory of 5 November 1688, during the sensitive period before William became king, included ‘Sithes 0’ and ‘Sithe blades 1’, at 4s 6d,Footnote 282 that is, they had been taken off display. In the following year, with the new regime now firmly established, they were reinstated, and the Yeoman Warders, short as ever on political correctness, no doubt made the most of them.

For the rest of the seventeenth century, although only ‘some’ scythes were on display in the Spanish Armoury, up to eighty-one others were listed among the ‘Spanish Weapons’, as shown by the inventories of 1689, 1690, 1691 and 1692–3,Footnote 283 presumably stored somewhere else. But by 1713, the year the next surviving inventory was compiled, their numbers had reduced to thirty-nine with staves and fifteen without,Footnote 284 and by the time of the next comprehensive inventory in 1859 there were only two.Footnote 285 Presumably, the remainder had been sold off or disposed of, or perhaps destroyed in the Grand Storehouse fire of 1841.

There is no reason to doubt, however, that some scythes remained on display in the first half of the eighteenth century. While they are not mentioned in the first guidebook – Thomas Boreman’s Curiosities in the Tower of 1741 (although trophies of ‘the last rebellion in the year 1715’ garner a few lines)Footnote 286 – they do appear in the anonymous Historical Account of the Tower of London and its Curiosities, printed in 1754 and 1759, described as ‘Some Weapons made with part of a Scythe fixed to a Pole which were taken from the Duke of Monmouth’s Party at the Battle of Sedgemoor in the reign of James ii’.Footnote 287 Very similar or identical terms were used in editions of 1768, 1774, 1784, 1789 and 1791, and a plate used in the Surveys … (of London and environs) by Thornton (1784), Barnard (1791) and Skinner (1795) shows, among other items from the Spanish Armoury,Footnote 288 a pole-hafted scythe blade, missing its heel (probably vii.961), along with the ‘Saxon’s sword’ (see fig 4). Intermittent reference to the scythes was made in guidebook editions of the next decades – being omitted in 1800 and 1801, included in 1803, and omitted again in 1810.Footnote 289 By 1817, however, they were back in favour, the guidebook pointing visitors to ‘A PIECE OF A SCYTHE placed on a pole, being a specimen of weapons taken at the battle of Sedgmoor’.Footnote 290

In 1827 the Spanish Armoury display was rearranged, and in 1831, taking up an earlier suggestion by Samuel Meyrick, pioneer historian of arms and armour, it was re-named ‘Queen Elizabeth’s Armoury’.Footnote 291 In 1837 it was re-housed in the barrel-vaulted eleventh-century room beneath St John’s chapel in the White Tower,Footnote 292 fitted up for the purpose with faux Norman arcading, wall shafts and vaulting ribs. Here, the 1839 guidebook tells us that ‘upon the last pillars are weapons used by the rebels at … Sedgemoor’,Footnote 293 and John Hewitt, in The Tower: its history, armories and antiquities of 1841, notes in Queen Elizabeth’s Armoury ‘Two scythe blades mounted on staves, and used by the rebels at the battle of Sedgemoor in 1685’,Footnote 294 as does J Wheeler’s A Short History of the Tower of London of the same year.Footnote 295 T B Macaulay, writing in the 1840s, noted that among Monmouth’s weapons improvised from the ‘tools they had used in husbandry or mining … the most formidable was made by fastening the blade of a scythe erect on a strong pole’, and that ‘One of these weapons may still be seen in the Tower’.Footnote 296 An engraving of 1840 of the ‘Norman Armoury’ (that is, the room re-fitted in 1837) appears to show one of them, bunched together with other staff weapons, close to its south-west corner.Footnote 297 They appear again under ‘Queen Elizabeth’s Armoury’ in a ms catalogue of 1857 (‘Weapon scythe used by the rebels at Sedgmoor 1685’),Footnote 298 and in 1860 the ‘scythe-blade weapons of Monmouth’s rustics’ were deemed sufficiently interesting to be named among other highlights in a piece in the Gentleman’s Magazine promoting John Hewitt’s Catalogue of 1859,Footnote 299 in which they are described.Footnote 300

In 1869, however, further changes – these by the dramatist, antiquary and polymath, James Robinson Planché – were made to most of the displays in the White Tower and the Horse ArmouryFootnote 301 with the blessing of the War Office.Footnote 302 In the process, Planché re-ordered the contents of the ‘upper room … which has for so many years borne the application of Queen Elizabeth’s Armoury’, removing ‘all specimens of a later date than 1603 to other parts of the building’, presumably including the scythes.Footnote 303 Between 1878 and 1881, prompted by the recent restoration of St John’s chapel above, the mock-Norman décor was removed,Footnote 304 and by August 1885 the remaining contents of the Armoury had been transferred to the western room on the second floor, by then described as the ‘Council Chamber’.Footnote 305

The successive movements of Monmouth’s scythes around the building after the 1880s need not be set out here, nor their mentions in guidebooks cited,Footnote 306 but they were last displayed from 1996 to 2013 in a part re-creation of the Spanish Armoury in the chapel undercroft. Currently in store, they will no doubt have a place in the emerging plans for the transformation of the Royal Armouries’ Museum in Leeds, and their history and significance, and that of the re-hafted scythe in general, explained and illustrated to the extent that they deserve.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the following individuals for their help and advice during the preparation of this article: Philip Abbott, John Aron, Janos Bak, Matthew Bennett, Paul Binski, David Birchall, Aleksandra Bukowska, Emma Carver, Esther Chadwick, John Childs, Mariuz Cieśla, Bridget Clifford, Ben Cowell, Anne Curry, Krzysztof Czyżewski, Kelly de Vries, Oliver Douglas, Keith Dowen, Michał Dziewulski, John Elliott, Jonathan Ferguson, Daniel FitzEdward, Jeffrey Forgeng, Paul Freedman, David Guillet, Nick Hall, Kate Harris, Erika Hebeisen, Michael Hieatt, Marc Höchner, Phillip Hocking, Pamela Hunter, Ronald Hutton, Jane Impey, Stuart Ivinson, Emilia Jastrzebska, Anna Keay, Ulrich Kinder, Annette Kniep, Marta Kulikowska, Padej Kumlertsakul, Donald La Rocca, Stefan Maeder, Malcolm Mercer, Mark Murray-Flutter, Romuald Nowak, Jan Ostrowski, Joseph Pack, Sofia Peller, Peter Petutschnig, Françoise Pineau, Sabina Potaczek, Olivier Renaudeau, Matthew Rice, Stefano Rinaldi, Holger Schuckelt, Markus Schwellensattl, Christopher Scott, Tadas Šėma, Kathryn Sibson, Mary Silverton, Peter Smithhurst, Anna Taborska, Marek Tobolka, Lisa Traynor, Bob Wayne, Bob Woosnam-Savage, Henry Yallop and Pawel Żurkowski.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material for this article is available online and can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581519000143

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- Bodleian

Bodleian Library, Oxford

- BL

British Library, London

- Brit Mag Month Regi Relig Ecclesias Info

The British Magazine and Monthly Register of Religious and Ecclesiastical Information

- HMC

Historical Manuscripts Commission

- J Galway Arch Hist Soc

Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society

- RA

Royal Armouries

- SHC

Somerset Heritage Centre

- TNA

The National Archives, Kew