Dementia is a major cause of disability for the world's older population, representing the biggest global challenge of the 21st century.Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley and Ames1 Around 50 million people live with dementia worldwide, with prevalence rates expected to triple by 2050.Reference Prince, Bryce, Albanese, Wimo, Ribeiro and Ferri2 Given the lack of disease-modifying treatments, the identification and prevention of modifiable risk factors for dementia is an important public health priority.Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley and Ames1 Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has recently been identified as a potential risk factor for developing dementia.Reference Yaffe, Vittinghoff, Lindquist, Barnes, Covinsky and Neylan3–Reference Desmarais, Weidman, Wassef, Bruneau, Friedland and Bajsarowicz5 However, despite the increased importance of this association across a range of populations, evidence of the magnitude of this relationship and potential mechanisms remain unknown. PTSD is a stress-related disorder developing after exposure to a traumatic stressor such as (threatened) death, serious injury or abuse,6 with an increased conditional risk of a PTSD diagnosis around 4%.Reference Atwoli, Stein, Koenen and McLaughlin7 Symptoms of PTSD, such as re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoidance and hypervigilance, often remain untreated for years, resulting in a chronic condition severe enough to affect daily functioning.Reference Bryant8,Reference Wang, Berglund, Olfson, Pincus, Wells and Kessler9

PTSD is understood to arise as a result of strong negative appraisals of the trauma and disturbances in autobiographical memory.Reference Ehlers and Clark10 Recent studies show that PTSD is associated with poor cognitive outcomes in several neurocognitive domains, such as processing speed, attention and working memory.Reference Friedman, Salzman, Neria, Small, Brickman and Ciarleglio11 Neural structural changes contributing to poor cognitive function have also been observed, although evidence suggests that the association between PTSD and impaired cognition is bidirectional.Reference Patel, Spreng, Shin and Girard12 Given the complexity of multiple risk factors contributing to dementia, estimating the risk associated with PTSD is important for informing future preventive strategies.Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley and Ames1

Although a systematic review examining the relationship between PTSD and dementia is now available,Reference Desmarais, Weidman, Wassef, Bruneau, Friedland and Bajsarowicz5 there are currently no meta-analyses. Given the lack of data on the magnitude of the relationship between PTSD and dementia, and a number of new studies being published, our primary objective in this study was to conduct the first meta-analysis of the relationship between PTSD and all-cause dementia in the literature. A secondary objective was to review the quality of the evidence.

Method

We followed current guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analysesReference Moher, Shamseer, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati and Petticrew13 and registered the review with PROSPEROReference Günak, Billings, Marchant, Carratu, Favarato and Orgeta14 (CRD42019130392).

Search strategy

We searched nine databases (MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, EThOS, OpenGrey, HMIC and Google Scholar) up to 25 October 2019, using a comprehensive list of search terms (see supplementary material, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.150). We additionally hand-searched reference lists of relevant reviews in the area. Two reviewers (M.M.G. and E.C.) independently screened abstracts of the first 50% of all articles identified, resulting in an interrater agreement of 99.59% (κ = 0.83, 95% CI 0.74–0.91, P < 0.001). The remaining studies were screened by the first reviewer (M.M.G.). All full-text articles were independently reviewed by M.M.G. and E.C., with any disagreements discussed with a third reviewer (V.O.).

Selection criteria

We included prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies investigating the association between PTSD and dementia. The population was adults (aged ≥18 years), and the comparison group was adults without PTSD. We included studies where a diagnosis of PTSD was based on: (a) clinical diagnostic criteria (i.e. ICD-9 or ICD-10,15 DSM-III, DSM-IV or DSM-56 or comparable) or (b) a validated self-report scale. Studies that did not diagnose dementia on the basis of clinical criteria (e.g. NINCDS-ADRDAReference McKhann, Drachman, Folstein, Katzman, Price and Stadlan16) were excluded.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (M.M.G. and E.C.) and included: (a) study design, (b) participant characteristics, (c) outcome measures and (d) risk of bias assessments. Five study authors were contacted for missing data, of whom three provided data. Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias using a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS),Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell, Peterson, Welch and Losos17,Reference Mata, Ramos, Bansal, Khan, Guille and Di Angelantonio18 addressing: (a) selection (i.e. representativeness, sample size, ascertainment of PTSD; dementia not present at baseline), (b) comparability and design (study controlling for ≥2 covariates, longitudinal design) and (c) outcome (assessment of dementia and follow-up ≥5 years; Table 1 and supplementary material). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. We extracted hazard ratios (HRs) and odds ratios (ORs); and conducted separate meta-analyses as recommended.Reference Stare and Maucort-Boulch19

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

M, mean; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CAPS-IV-TR, Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV-TR; NINCDS-ADRDA, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; NINDS-AIREN, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

a. If not stated otherwise, effect estimate of dementia incidence in PTSD against non-PTSD sample.

b. Not included in the meta-analyses.

Statistical analysis

We used the generic inverse variance method with a random-effects model to obtain a pooled risk estimate for studies reporting hazard ratios, and a fixed-effects model for studies reporting odds ratios,Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein20 using adjusted ratios where possible. We measured heterogeneity by the chi-squared Cochran's Q-test and the I 2-statistic, and where heterogeneity was detected, we calculated prediction intervals.Reference Riley, Higgins and Deeks21 Sources of heterogeneity were explored by performing both subgroup and sensitivity analyses. We additionally examined the impact of each individual study and effect of study quality. We were not able to perform meta-regression as there were fewer than ten studies that adjusted for the same potential effect modifiersReference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein22 (e.g. only five studies adjusted for traumatic brain injury; Table 2). Publication bias was assessed via a funnel plot and the Egger test.Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder23 STATA (version 15.1.) for Windows and the metan commands were used for all meta-analyses.

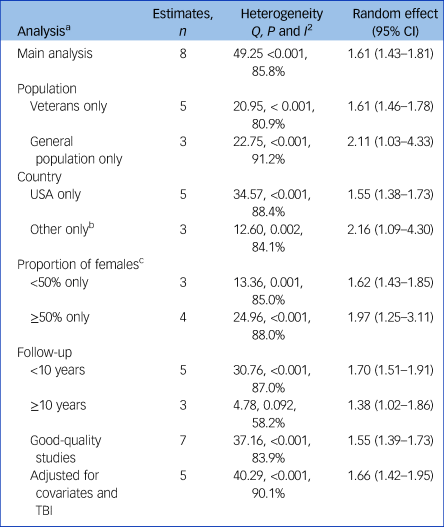

Table 2 Meta-analysis, subgroup and sensitivity analyses of the association of post-traumatic stress disorder and dementia

TBI, traumatic brain injury.

a. All subgroup and sensitivity analyses include studies of hazard ratios only.

b. One study each conducted in Taiwan, Denmark and Australia.

c. One study excluded because of missing values.

Results

Study selection

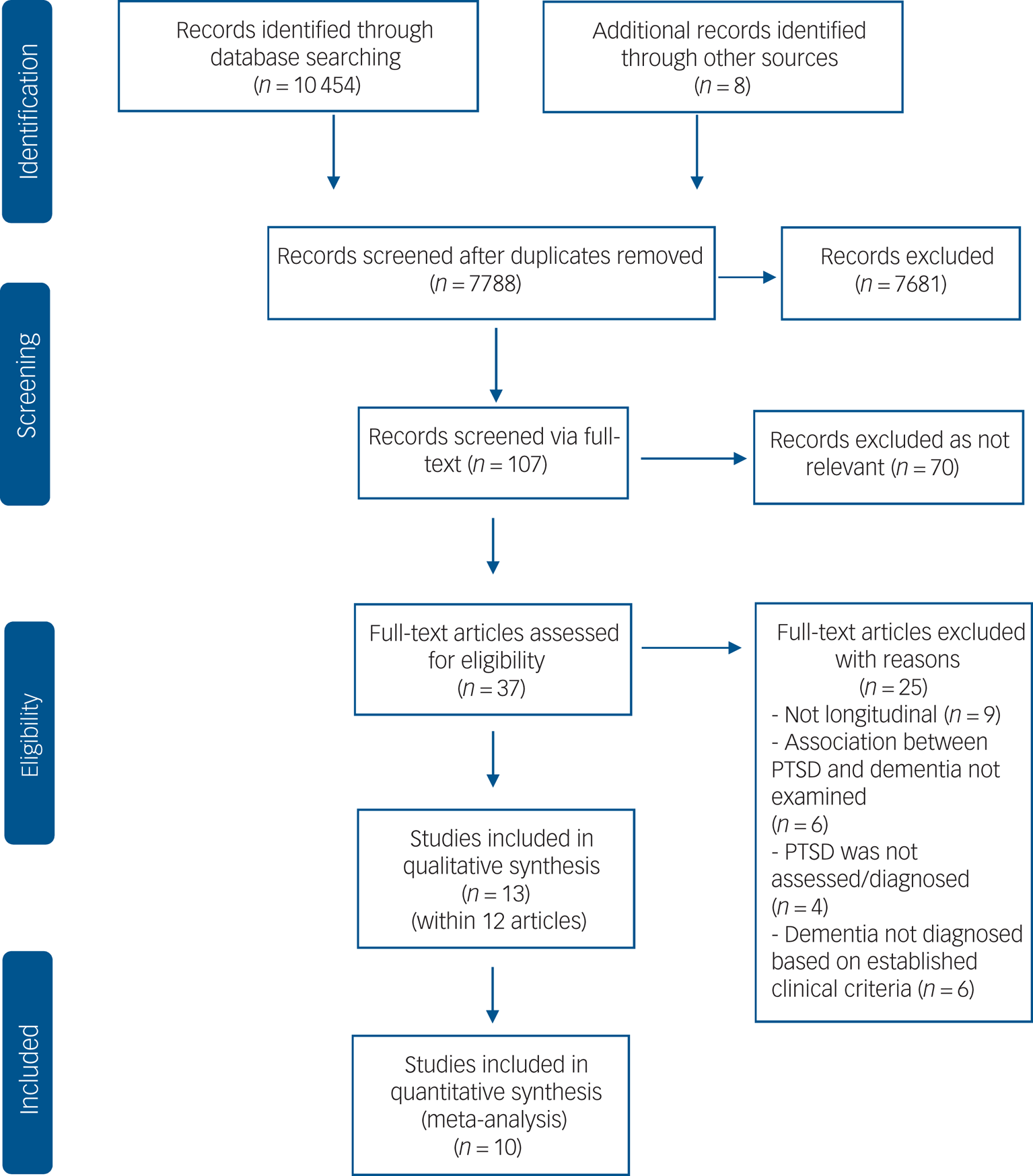

We identified a total of 10 462 references (Fig. 1), and after removal of duplicates and irrelevant articles, we retrieved 107 full-text records. Of these, 70 were excluded as not relevant, leaving 37 full-text references to be fully assessed for eligibility. Of these, 25 studies were excluded with reasons (see supplementary material), leaving a total of 12 studies meeting inclusion criteria, with one study reporting on two independent samples. We pooled data from 10 studies in our meta-analyses.

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the search and study selection process.

Study characteristics

All included studies were longitudinal cohort studies, with the majority being retrospective, deriving diagnoses from medical records. Reporting of follow-up varied from 1 to 17 years (Mdn = 9 years). All studies except two compared dementia rates in the PTSD group (i.e. PTSD at baseline) with those in a control group (i.e. no PTSD at baseline). Roughead et alReference Roughead, Pratt, Kalisch Ellett, Ramsay, Barratt and Morris24 compared two PTSD groups with differing PTSD severity, which they classified as hospitalised (severe PTSD) versus non-hospitalised (less severe PTSD). We included the severe PTSD group in our meta-analysis, as in this group, PTSD diagnosis was based on clinical criteria.

Sample sizes ranged from 46 to 499 844 (Mdn = 15 612), with 1 693 678 participants in total. Age of participants ranged from 51 to 73.6 years, with 7 studies on veterans, 5 studies on the general population and 1 study on war refugees. The percentage of females varied from 0.1 to 76.6%, with 2 studies recruiting either male or female veterans only.Reference Roughead, Pratt, Kalisch Ellett, Ramsay, Barratt and Morris24,Reference Yaffe, Lwi, Hoang, Xia, Barnes and Maguen25 Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Nine studies scored in the higher range of methodological quality (supplementary material). Four studiesReference Wang, Wei, Liou, Su, Bai and Tsai26–Reference Bonanni, Franciotti, Martinotti, Vellante, Flacco and Di Giannantonio28 were judged to be of poor quality. Methodological domains where there was evidence of risk of bias included study design (i.e. retrospective), no comparison control group and no data as to whether dementia was present at baseline.

Primary meta-analysis of PTSD and risk of dementia

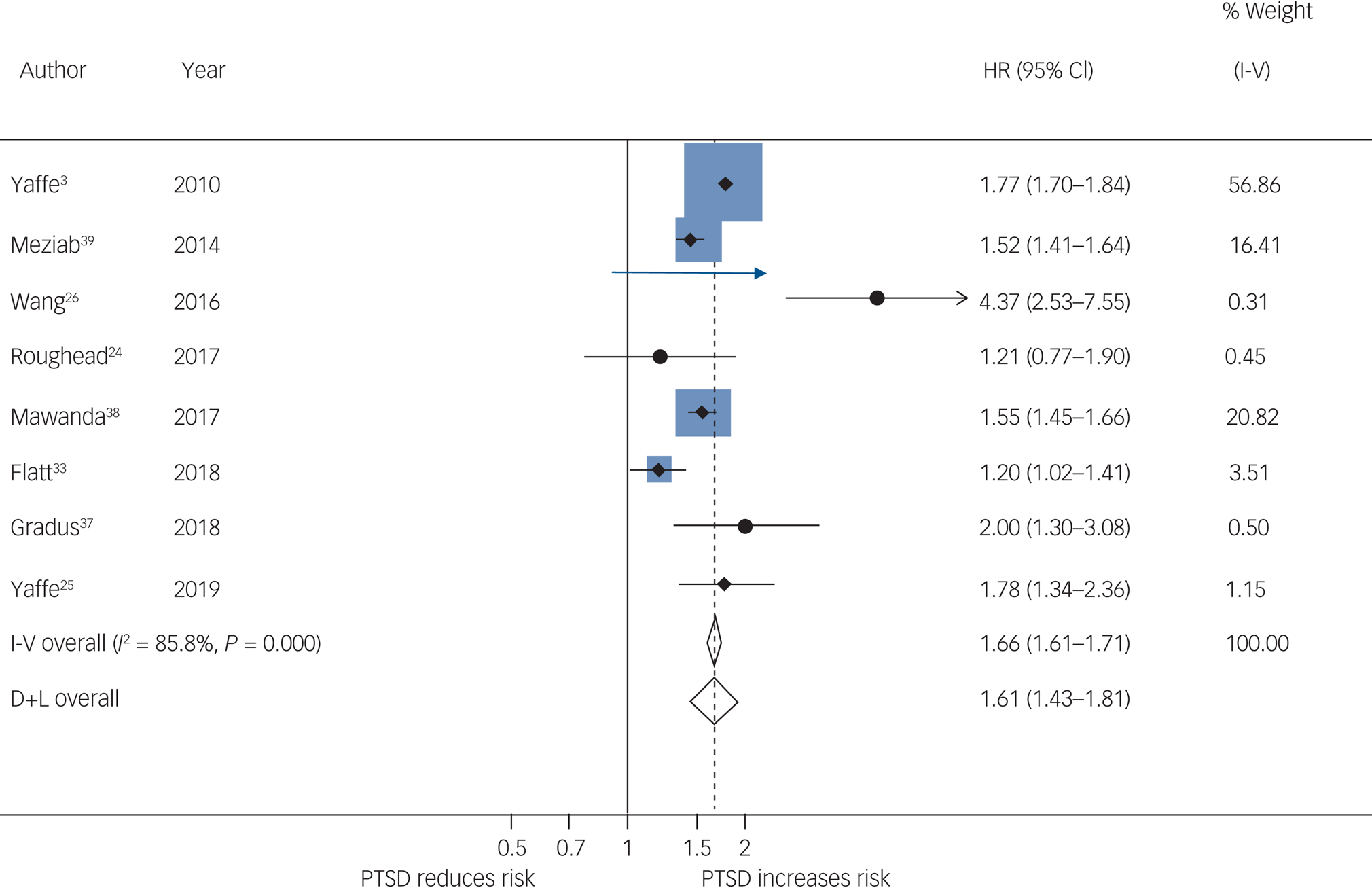

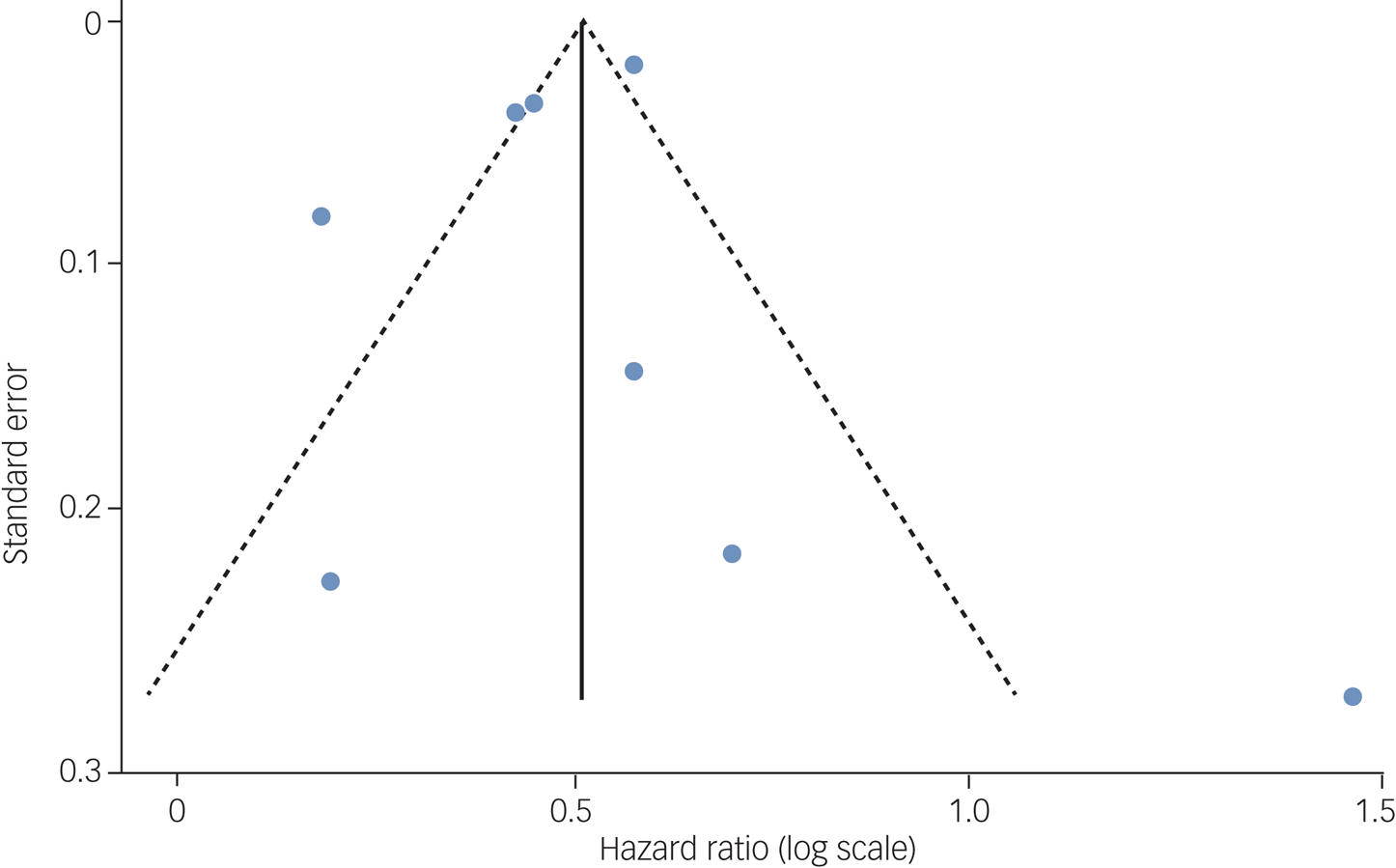

Pooled results from 8 studies showed that PTSD increased risk of all-cause dementia: pooled HR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.43–1.81, I 2 = 85.8%, P < 0.001; 1 693 678 participants in total, 89 493 of whom had PTSD; median follow-up of 9 years (Fig. 2); 95% prediction interval of 1.14 to 2.29. Visual inspection of the funnel plot (Fig. 3) suggested no publication bias, which was supported by the Egger test (t = −0.30, P = 0.771).

Fig. 2 Meta-analysis of hazard ratios of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared with no PTSD on risk of dementia.

I-V, Inverse Variance method; D+L, DerSimonian and Laird method.

Fig. 3 Funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits to inspect publication bias.

Pooling studies reporting odds ratios (two studies) showed that PTSD increased dementia risk: OR = 1.99, 95% CI 1.69–2.35, I 2 = 65.1%, P = 0.090; 15 281 participants in total, 5260 of whom had PTSD; follow-up ranged from 1 to 9 years. Studies not included in the meta-analysis reported similar findings. In Folnegovič-Šmalc et al,Reference Folnegovič-Šmalc, Folnegovic, Uzun, Vilibic, Dujmic and Makaric27 war refugees with PTSD symptoms had a higher risk of dementia compared with non-war refugees. Bonanni et alReference Bonanni, Franciotti, Martinotti, Vellante, Flacco and Di Giannantonio28 found that a history of PTSD was more prevalent in people with dementia compared with people with any other neurological condition (study 2, retrospective). In their prospective study (study 1), reported in the same paper,Reference Bonanni, Franciotti, Martinotti, Vellante, Flacco and Di Giannantonio28 17.4% (n = 8) of those with PTSD (n = 46) were diagnosed with dementia during a 4-year follow-up, 6 of whom developed frontotemporal dementia.Reference Bonanni, Franciotti, Martinotti, Vellante, Flacco and Di Giannantonio28

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Subgroup analyses indicated that risk was higher in the general population than in veterans; pooled HR = 2.11, 95% CI 1.03–4.33, I 2 = 91.2%, P < 0.001, n = 787 782, compared with pooled HR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.46–1.78, I 2 = 80.9%, P < 0.001, n = 905 896 (Table 2). The effect was slightly higher in studies conducted in countries other than the USA than in studies in the USA: pooled HR = 2.16, 95% CI 1.09–4.30, I 2 = 84.1%, P = .002, n = 303 550, compared with pooled HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.38–1.73, I 2 = 88.4%, P < 0.001, n = 1 390 128. Risk was higher in studies that included ≥50% females compared with studies with <50% female participants: pooled HR = 1.97, 95% CI 1.25–3.11, I 2 = 88.0%, P = 0.001, n = 896 922, compared with pooled HR = 1.62, 95% CI 1.43–1.85, I 2 = 85.0%, P < 0.001, n = 613 778. Risk was also higher in studies with a maximum follow-up of <10 years compared with studies with ≥10 years follow-up: pooled HR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.51–1.91, I 2 = 87.0%, P < 0.001, n = 899 034, compared with pooled HR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.02–1.86, I 2 = 58.2%, P = 0.092, n = 794 644.

Excluding one study with high risk of biasReference Wang, Wei, Liou, Su, Bai and Tsai26 reduced the effect estimate but results remained statistically significant: pooled HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.39–1.73, I 2 = 83.9%, P < 0.001, n = 1 684 928. The direction and strength of the results remained the same after omitting any single study (supplementary material), with no study substantially affecting between-study heterogeneity (range I 2 = 80.8–87.8%, P < 0.001). Pooling only studies that adjusted for history of traumatic brain injury slightly increased the overall effect estimate: pooled HR = 1.66, 95% CI 1.42–1.95, I 2 = 90.1%, P < 0.001, n = 1 215 999. Adding both subgroups of the Roughead et al studyReference Roughead, Pratt, Kalisch Ellett, Ramsay, Barratt and Morris24 (severe and less severe PTSD) decreased risk, but results remained statistically significant: pooled HR = 1.52, 95% CI 1.33–1.73, I 2 = 89.5%, P < 0.001.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis quantifying the association between PTSD and risk of dementia. We performed a thorough search of almost 8000 records, including studies across a range of populations and countries. Our review found that PTSD is an important and potentially modifiable risk factor for all-cause dementia. Meta-analyses showed that the risk of being diagnosed with dementia for individuals with a diagnosis of PTSD is 1.61–1.99 times the risk for those without a PTSD diagnosis. We found that, after controlling for several confounders, the association between PTSD and dementia remained significant.

Subgroup analyses revealed that the effect in the general population is larger than the effect in veterans, with an increased risk of 111 and 61%, respectively. That is, in the general population, the risk of being diagnosed with dementia in individuals with PTSD is more than twice the risk in those with no PTSD diagnosis. In the veteran population with PTSD, however, the risk of dementia is more than one and a half times higher to that of veterans without PTSD. If the smaller risk observed in veterans is because they are more likely to receive treatment for PTSD than the general population, this may indicate that PTSD-related dementia risk could be modified by intervention. For example, in a sample of young to middle-aged individuals, veterans were more likely to have health insurance and receive counselling or psychotherapy compared with non-veterans.Reference Fortney, Curran, Hunt, Cheney, Lu and Valenstein29 Access to treatment for PTSD across populations may therefore differentially modify the association between PTSD and dementia.

It is likely that type of trauma, duration of exposure, and pre- and post-trauma environmental factors influence PTSD symptom severity and risk of dementia in different ways, across different populations. Traumatic brain injury, for example, which is independently associated with increased risk of dementia, is more prevalent in some populations.Reference Barnes, Kaup, Kirby, Byers, Diaz-Arrastia and Yaffe30 In our analysis, when adjusting for history of traumatic brain injury, counterintuitively the effect estimate increased. This may be explained by a mortality effect whereby individuals with traumatic brain injury die before they develop dementia.Reference Dutton, Stansbury, Leone, Kramer, Hess and Scalea31 Although both dementia and PTSD are more prevalent in females, current evidence is mixed in relation to whether gender modifies the association between PTSD and risk of dementia.Reference Roughead, Pratt, Kalisch Ellett, Ramsay, Barratt and Morris24–Reference Wang, Wei, Liou, Su, Bai and Tsai26,Reference Bhattarai, Oehlert, Multon and Sumerall32,Reference Flatt, Gilsanz, Quesenberry, Albers and Whitmer33 There may be a stronger association among females as the strength of the relationship increased when pooling studies in which ≥50% of the sample were women. The increased risk of dementia was highest when pooling studies with a maximum follow-up <10 years compared with the pooled risk of studies following participants for ≥10 years. This indicates that PTSD might be a prodrome of dementia and that brain vulnerability remains silent over many years.Reference Bryant8

Only one study reported no significant association between PTSD and dementia.Reference Roughead, Pratt, Kalisch Ellett, Ramsay, Barratt and Morris24 Roughead et alReference Roughead, Pratt, Kalisch Ellett, Ramsay, Barratt and Morris24 stratified their data by antipsychotic use and found that patients with PTSD who were prescribed antipsychotics had an increased risk of dementia compared with controls without PTSD and being prescribed antipsychotics. Given the limited data available, we were not able to examine the effect of antipsychotics as a potential confounder of the association between PTSD and dementia. Comprehensive reporting and harmonisation of potential modifiers across studies will be important for strengthening future meta-analyses.

Mechanisms

The mechanisms of the association between PTSD and dementia remain to a large extent unknown. It has been proposed that certain neurobiological pathways not specific to but potentiated by PTSD may increase risk of developing dementia.Reference Friedman, Salzman, Neria, Small, Brickman and Ciarleglio11,Reference Miller, Lin, Wolf and Miller34 These pathways include altered activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, reduction in hippocampal volume and oxidative stress,Reference Miller, Lin, Wolf and Miller34 which may in turn contribute to or accelerate dementia neuropathology.Reference Patel, Spreng, Shin and Girard12 Constant hypervigilance and recurrent re-experiencing of the trauma may activate threat- and stress-related neurobiological pathways,Reference Friedman, Salzman, Neria, Small, Brickman and Ciarleglio11,Reference Miller, Lin, Wolf and Miller34 increasing vulnerability to dementia. As PTSD symptoms develop, avoidance and withdrawal from daily and social life6 may result in diminished cognitive stimulation, reducing individuals’ cognitive reserve and resilience to neuropathological changes associated with dementia.Reference Stern35,Reference Stern, Gurland, Tatemichi, Tang, Wilder and Mayeux36 PTSD and dementia may also share common underlying genetic vulnerability, with pathways between the two being bidirectional.Reference Desmarais, Weidman, Wassef, Bruneau, Friedland and Bajsarowicz5,Reference Bryant8

Strengths and limitations

Our meta-analysis extends current knowledge by being the first study to quantify the association between PTSD and all-cause dementia. We used a comprehensive and sensitive strategy to identify studies and included longitudinal studies where PTSD was present before the onset of dementia. We have provided an up-to-date review of worldwide evidence of the association between PTSD and risk of dementia based on studies with long follow-up periods, reporting on data of almost two million participants. We conducted a series of subgroup and sensitivity analyses to explore heterogeneity, and the prediction interval observed in our meta-analysis is consistent with a significant and important increase in risk of dementia associated with PTSD.Reference Riley, Higgins and Deeks21

Despite these strengths, however, our review has several limitations. First, there was substantial statistical heterogeneity between studies, and even though several subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed, heterogeneity remained high and its sources could not be detected. Our second meta-analysis was based on only two studies and therefore remains limited.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein22 All included studies were observational cohort studies and most were retrospective. Generally, association does not equate with causation, and retrospective designs have important flaws. Given that many different healthcare professionals were involved in the diagnoses of PTSD and dementia, measurements may be less consistent and accurate compared with those achieved in the context of a prospective design. Additionally, the use of different definitions and classifications of PTSD across studies means that cut-offs will differ, influencing diagnosis or ‘caseness’.Reference Bryant8

Implications for the future

Future studies are needed to examine the specific contribution of environmental, trauma-related and neurocognitive mechanisms and how these may interact in increasing vulnerability to cognitive decline.Reference Bryant8,Reference Miller, Lin, Wolf and Miller34 Further studies are required to address how the use of different classifications of both PTSD and dementia may influence the estimate of the effect. An important question that arises from our systematic review is whether access to effective and timely treatment for PTSD could potentially reduce the risk of developing dementia. Future studies therefore should examine the prophylactic potential of treating PTSD and its contribution in preventing or delaying the onset of dementia.

Our review provides the first evidence that PTSD is a strong and potentially modifiable risk factor for all-cause dementia and, given the cost of dementia and its consequences for individuals and their families, PTSD prevention strategies should form part of worldwide public health initiatives.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.150.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the first and corresponding authors (M.M.G. and V.O.).

Acknowledgements

We thank Harriet Demnitz-King, Tim Whitfield and Marco Schlosser for their help and all authors who contributed data on request.

Author contributions

M.M.G.: conceptualisation of the review; selection of studies; data extraction; data entry; data analysis; data quality; writing, review and editing of manuscript. J.B.: conceptualisation of the review; review and editing of final draft. E.C.: conceptualisation of the review; selection of studies; data extraction; data quality; review and editing of final draft. N.L.M.: conceptualisation of the review; review and editing of final draft. G.F.: conceptualisation of the review; data analysis; review and editing of final draft. V.O.: conceptualisation of the review; selection of studies; data quality; writing, review and editing of manuscript.

Funding

This review did not receive any specific funding. J.B., N.L.M., G.F. and V.O. are supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. N.L.M. is supported by a Senior Fellowship from the Alzheimer's Society (AS-SF-15b-002). V.O. was funded by an Alzheimer's Society Senior Research Fellowship while undertaking this research (AS-SF-15-005).

Declaration of interest

N.L.M. and V.O. report grants from the Alzheimer's Society during the conduct of the study.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.150

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.