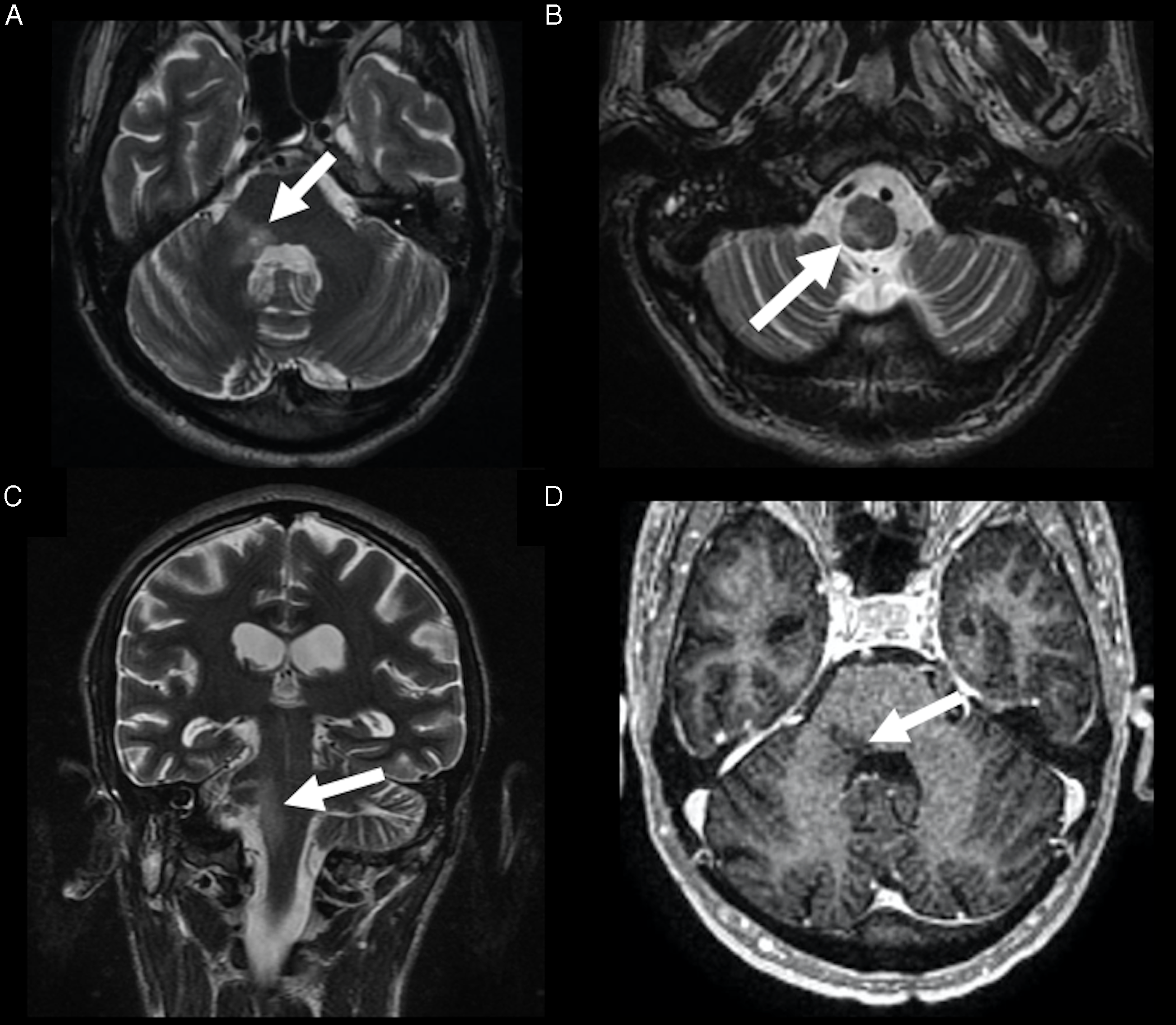

A 37-year-old man, recently diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, with a viral load of 64 copies/mL and CD4+ lymphocyte count of 204 cells/mm3, with no antiretroviral treatment, presented with fever, dysarthria, and right hemifacial paresthesia for 2 weeks, evolving with dysphagia and choking. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a lesion with hyperintense signal on T2-weighted imaging in the right dorsolateral pons extending inferiorly to the medulla, with no gadolinium enhancement (Figure 1). The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination revealed a clear liquid, mild pleocytosis, with 70 white blood cells/mm3 (85% of lymphocytes), no red blood cells, with normal protein and glucose levels. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the CSF was positive for cytomegalovirus (CMV), with 800 copies/mL (normal range: <500 copies/mL). PCR was performed combined with real-time homogeneous fluorescence detection for CMV DNA quantification, validated for use in the CSF. PCR was negative for herpes simplex viruses, varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Epstein–Barr virus, enterovirus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Venereal Disease Research Laboratory was negative. Blood and CSF cultures were negative, including for Listeria monocytogenes. Serum and CSF cell-based assay for anti-aquaporin 4 antibodies were negative. The patient was diagnosed with CMV rhombencephalitis and treated with intravenous ganciclovir. Serology for CMV and PCR for CMV in the blood were not performed. Highly active antiretroviral therapy was started, with zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz. One month after the beginning of treatment, the patient was discharged without fever and choking, and partial improvement of the dysarthria, hemifacial paresthesia, and dysphagia.

Figure 1: Rhombencephalitis caused by CMV. Brain MRI demonstrated a hyperintense lesion on T2-weighted imaging, in the right dorsolateral pons (arrow in A), extending through the medulla (arrow in B), in the axial (A and B) and coronal planes (arrow in C), with no gadolinium enhancement (arrow in D).

CMV is a member of the Herpesviridae family, Reference Andreula1 commonly infecting humans before their first year of life. Reference Studahl, Lindquist and Eriksson2 It is a neurotropic virus, whose congenital infection is an important health concern. However, neurological manifestations are rare in adults, usually limited to immunosuppressed patients, due to viral reactivation, often characterized by polyradiculomyelitis, retinitis and, less commonly, encephalitis. CMV encephalitis can be a diagnostic challenge, due to atypical clinical and neuroimaging findings. Basal ganglia, diencephalon, and brainstem are the main sites of CMV infection. Reference Ludlow, Kortekaas and Herden3

A hallmark of herpesviruses family is lifelong latency in specific cells and intermittent reactivations, leading to asymptomatic virus release or recrudescent disease, during periods of relative immunosuppression. Furthermore, neurotropism is other feature of the herpesviruses. After the primary infection, these viruses can remain latent in the neurons, later seeding through the central nervous system (CNS) across endothelial cells or retrogradely along the nerves. Reference Baskin and Hedlund4 VZV is the herpesvirus that most commonly causes rhombencephalitis due to reactivation, with retrograde neural spread. Previous studies reported cases of rhombencephalitis, caused by VZV, with nucleus of the solitary tract, nucleus ambiguus, spinal trigeminal nucleus, and/or vestibular nuclei involvement. Reference Kim, Chung and Oh5–Reference Inagaki, Toyoda, Mutou and Murakami7 Although rarely, CMV also causes rhombencephalitis, usually associated with immunosuppression, Reference Jubelt, Mihai, Li and Veerapaneni8 affecting the dorsal portion of the medulla, in these nuclei regions, similar to our case. Reference Katchanov, Branding and Stocker9 Although we did not perform serology and PCR for CMV in the blood, the PCR for CMV was positive in the CSF and negative for the other tested infectious agents. Also, the patient’s symptoms improved after treatment.

Rhombencephalitis encompasses any inflammatory disease affecting the hindbrain, which in turn is composed of the pons, medulla, and cerebellum. The etiology of rhombencephalitis can be classified as infectious or inflammatory. Reference Jubelt, Mihai, Li and Veerapaneni8 The most common causes of infectious rhomboencephalitis are Listeria monocytogenes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Other important causes of infectious rhombencephalitis are Enterovirus 71, and Mycoplasma pneumonia, in addition to the Herpesviridae family. Although brain MRI alone cannot determine the responsible infectious agent, infectious rhombencephalitis demonstrates hyperintense signal on T2-weighted imaging and FLAIR, as in our case, which may be associated with leptomeningeal enhancement and mass effect. In addition, other diseases that should be considered with this imaging aspect are demyelinating disease, such as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, vasculitis, such as Behçet’s disease, and neoplasms, mainly glioma and lymphoma. However, demyelinating diseases may present lesions in other parts of the CNS and optic nerves; vasculitis may present typical clinical manifestations, such as oral and genital ulcers in Behçet’s disease; tumors usually demonstrate a greater expansive effect, with diffuse enlargement of the brainstem, which may be associated with parenchymal enhancement, signs of hyperperfusion or restricted diffusion. Reference Renard, Guillamo, Ion and Thouvenot10

Therefore, it is important to consider CMV rhombencephalitis in the differential diagnosis of brainstem lesions, especially in immunosuppressed patients.

Statement of Authorship

TLS undertook conception, drafted the article, and had final approval of the last version.

WCHC collected the patient data, edited the article, and had final approval of the last version.

DGC edited the article, provided direct supervision, and had final approval of the last version.

Disclosures

The authors do not have anything to disclose.