The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh1 and its revised version (BDI-II) are some of the most frequently used self-rating scales for measuring the severity of depressive symptoms.Reference Richter, Werner, Heerlein, Kraus and Sauer2 The BDI was originally developed based on clinical experience and aimed to assess the varying intensity of depression.Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh1 It underwent two major revisions in 1978Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery3 and 1996,Reference Beck, Steer and Brown4 as the BDI-IA and BDI-II, respectively. The BDI-II was modified to better recognise severe depression, possibly demanding hospital care.Reference Beck, Steer and Brown4

BDI-II in different populations

Reportedly, studies have shown that culture affects the way we express emotions,Reference Markus and Kitayama5 often leading to misinterpretation of symptoms by clinicians.Reference Kirmayer6 Psychological research has mostly been conducted in Western countries and among Western study samples, which do not culturally represent global diversity.Reference Thalmayer, Toscanelli and Arnett7 Since the publication of the BDI-II, its psychometric properties have been studied on several different occasions, in different cultures and subgroups, although not always in representative samples.Reference Arnarson, Ólason, Smári and Sigurdsson8–Reference Harris and D'Eon10 Studies have shown that the reliability and validity of the BDI-II, measured by Cronbach's alpha, Spearman's rank correlation and Student's t-test, is good across different subgroups, including when used in different language versions.Reference Toledano-Toledano and Contreras-Valdez11,Reference García-Batista, Guerra-Peña, Cano-Vindel, Herrera-Martínez and Medrano12 On the contrary, different cut-off points have been suggested for the studied subgroup in some study settings, such as a cut-off score of ≥27 to differentiate veterans with mood disorder.Reference Reis, Namekata, Oehlert and King13 In addition, population-based studies on the psychometric properties and validity of the BDI-II included a description of the distribution of the item scores of the BDI-II.Reference García-Batista, Guerra-Peña, Cano-Vindel, Herrera-Martínez and Medrano12,Reference Aasen14–Reference Kojima, Furukawa, Takahashi, Kawai, Nagaya and Tokudome17 However, there are few studies describing the distribution of symptoms in representative population-based samples.

The original BDI scale has been shown to be a valid screening measure for depression in Finland.Reference Nuevo, Lehtinen, Reyna-Liberato and Ayuso-Mateos18 and a reliable tool for cross-cultural comparison in Europe, although some cross-cultural differences have been noticed, especially in the Spanish sample.Reference Nuevo, Dunn, Dowrick, Vázquez-Barquero, Casey and Dalgard19 The Finnish translation of the BDI-II was published in 2004.20 Since then, the BDI-II questionnaire has been used in clinicalReference Granö, Salmijärvi, Karjalainen, Kallionpää, Roine and Taylor21–Reference Weizmann-Henelius23 and population-based studies,Reference Hintsa, Wesolowska, Elovainio, Strelau, Pulkki-Råback and Keltikangas-Järvinen24–Reference Poutanen, Koivisto and Salokangas26 but the individual items of the questionnaire have not been examined in the Finnish population since the translation. In addition, neither were the Finnish population symptom scores compared with the corresponding population scores from other countries.

Aim of the study

Although the BDI-II is a commonly used tool for measuring depressive symptoms worldwide, with some cultural differences being reported,Reference Dere, Watters, Yu, Michael Bagby, Ryder and Harkness27,Reference Whisman, Judd, Whiteford and Gelhorn28 no item-by-item comparison of the BDI-II across different countries and population-based samples has been made. To improve the cross-cultural interpretation of the BDI-II, this population-based study described the symptoms measured on the BDI-II in the Finnish population, and compared the distribution of items between population-based samples from six different countries.

Method

Finnish study population

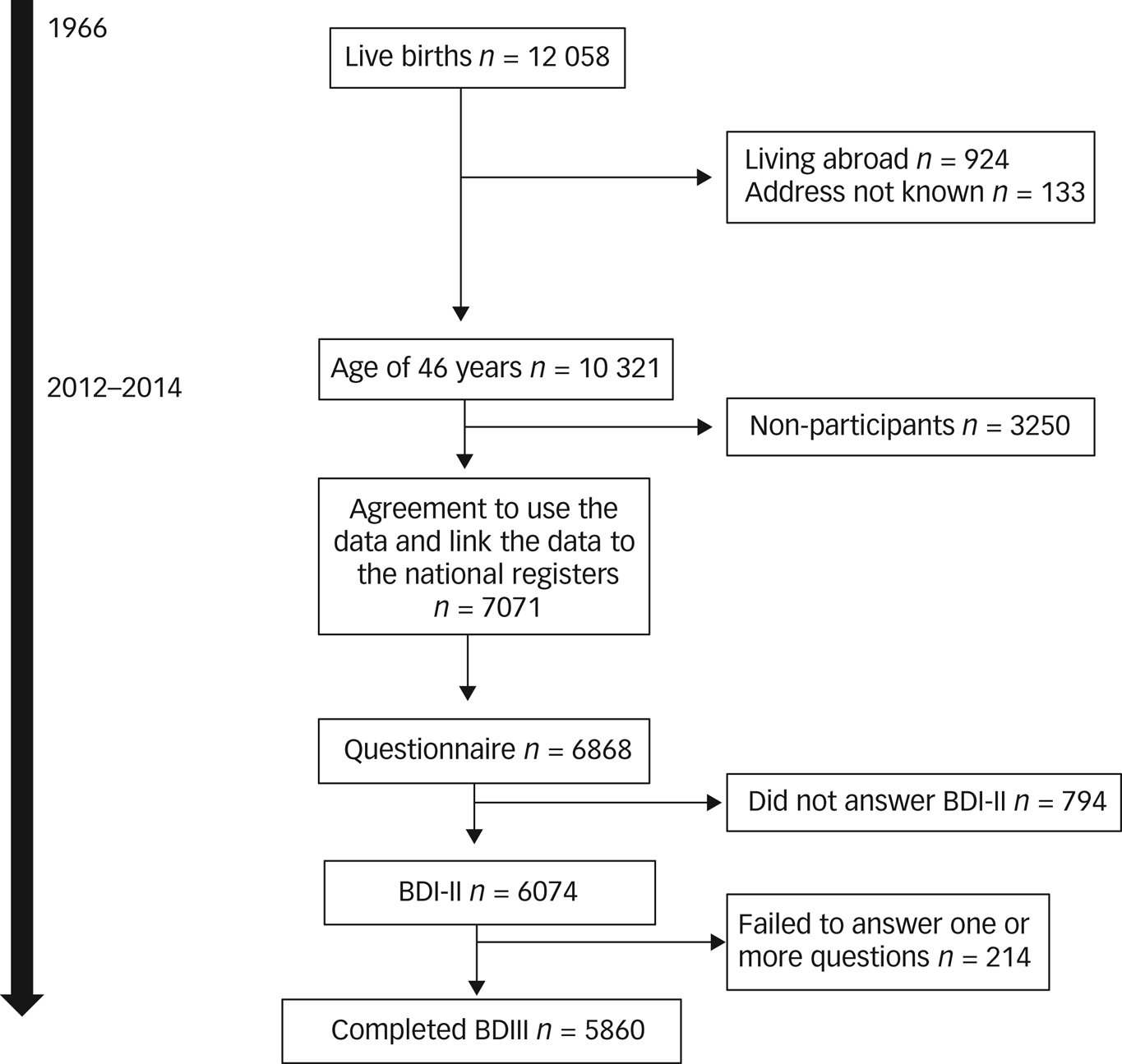

The Finnish population was based on the Northern Finland Birth Cohort (NFBC) 1966,29 which is a longitudinal research programme that originally included all of the mothers (n = 12 068)Reference Rantakallio30 with children (n = 12 058 live-born individuals) whose expected date of birth fell in the year 1966. The cohort members were monitored through interviews, postal questionnaires and clinical measurements from the prenatal period onward. The data from the most recent time point when the individuals were 46 years old (n = 10 321 alive) were included in this study (see Fig. 1). Questionnaire data at 46 years were received from 6868 (67%) participants and clinical examination data were received from 5860 (57%) participants. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human participants were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District in Oulu, Finland (approval number 94/2011). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Personal identity information was encrypted and replaced with identification codes.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of the participants who completed the BDI-II questionnaire in the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966. BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II.

Selection of international populations

We searched SCOPUS, PsycINFO and PubMed for studies on the BDI-II. The search was conducted manually on 22 June 2020, using the following keywords: BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory II, validation, population, psychometr*, adaptation and dimension. The search strategy was developed in cooperation with a health science librarian using medical subject headings, and adapted for other databases by using free-word searches. The search strings were defined and validated by the first author (M.S.) together with the librarian. M.S. performed the initial search and screened the titles and abstracts of all of the articles identified by the search strings, to exclude irrelevant articles according to the eligibility criteria. Furthermore, we included original peer-reviewed journal articles, including mean values of BDI-II items based on population-based samples. The articles included in the analyses were required to meet the following criteria: used the BDI-II, reported the mean BDI-II value and mean and s.d. for each BDI-II item, and used population-based sampling. The search results were limited to human studies and English-language articles made available through open access or otherwise accessible within the University of Oulu. The search results were not limited by date. Additional articles were identified by searching the references in papers retrieved by the search strategy. The initial literature search retrieved 522 articles; however, after removing duplicate articles, screening of titles and abstracts, and reading of full-text articles, five articles were finally considered eligible for inclusion in this comparative study.

International populations

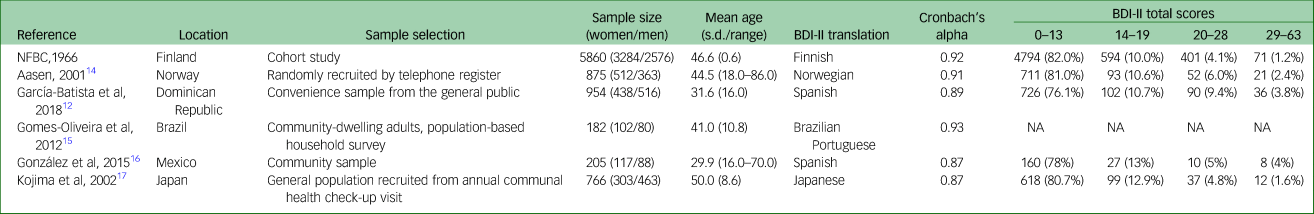

The eligible studies selected for the comparison were conducted in Norway (n = 875),Reference Aasen14 the Dominican Republic (n = 954),Reference García-Batista, Guerra-Peña, Cano-Vindel, Herrera-Martínez and Medrano12 Brazil (n = 182),Reference Gomes-Oliveira, Gorenstein, Neto, Andrade and Wang15 Mexico (n = 205)Reference González, Rodríguez and Reyes-Lagunes16 and Japan (n = 766).Reference Kojima, Furukawa, Takahashi, Kawai, Nagaya and Tokudome17 The selected studies are summarised in Table 1. The mean number of individuals included in the studies was 603 (s.d. 378), ranging from 182 to 954. Sample recruitment varied between studies. All of the study populations were adults or adolescents with a mean age of 40.6 years (range 29.9–50.0 years). The studies were conducted in 2001, 2002, 2012, 2015 and 2018.

Table 1 Summary table of studies included in the present comparison

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; NFBC, Northern Finland Birth Cohort.

Instrument

Depression was evaluated with the BDI-II questionnaire, which consists of 21 questions and answers, each scoring from 0 to 3 points. The total score of BDI-II can be calculated (0–63), and a cut-off of 0–13 points indicates minimal depressive symptoms, 14–19 points indicates mild depressive symptoms, 20–28 points indicates moderate depressive symptoms and 29–63 points indicates severe depressive symptoms.Reference Beck, Steer and Brown4 All study populations used a translated version of the questionnaire, and samples had adequate internal consistency as measured by Cronbach's alpha, ranging from 0.87 to 0.93. We present the detailed information regarding cut-off distributions and measures for internal consistency in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

We present the original BDI-II item means for each study in Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.13. As the samples differed by total BDI-II scores and we wanted to compare the relative importance of each item, we calculated the relative means for the items by dividing the mean value of each symptom with the total mean, and then divided by the number of BDI-II items (item mean/(total mean/21)). A relative mean <1 in an item can be interpreted so that the symptom in question has a mean score below an average item mean in the sample in question; if the mean is >1, the mean score is above an average item mean. Based on these relative mean scores, we first used random-effects meta-analysis to pool the six different populations, and then used meta-regression to statistically compare the results of these populations. This was done by comparing each sample to the average of the other samples. Visual examination of relative mean scores and results of meta-regression was done by using spider charts. The results are expressed as P-values and 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.05. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 for Windows, and meta-analysis was conducted with Stata version 16 for Windows.

Results

Finnish population

Overall, 6074 participants completed the BDI-II questionnaire either on the day of the health examination or at home after receiving the questionnaire by mail; 214 participants failed to answer 1–14 questions. All of the those with missing values were excluded. The final study sample consisted of 5860 participants, of whom 2576 (46.2%) were men and 3284 (53.8%) were women. Most of the participants had good or excellent self-rated health (n = 3755, 64.1%), and 1577 (26.9%) had higher education. Of those who failed to complete the BDI-II questionnaire, 92 (43.0%) were men and 122 (57.0%) were women. The three items most likely to be missed were ‘loss of energy’ (n = 140, 65.4% missing values), ‘tiredness or fatigue’ (n = 139, 65.0%) and ‘loss of interest in sex’ (n = 139, 65.0%). Women were most likely not to respond to the question regarding loss of energy, whereas men were most likely not to respond to the question regarding loss of interest in sex. The average total of BDI-II points was 5.55 (s.d. 0.08), with a minimum value of 0 and a maximum value of 55. Ten per cent (n = 594) of the final study population scored at least 14 points (showing mild depressive symptoms) in the BDI-II questionnaire, 4.1% (n = 401) scored at least 20 points (showing moderate depressive symptoms) and 1.2% (n = 71) scored at least 29 points (showing severe depression symptoms). Most of the individuals with depression were women (66.2%). The mean values of BDI-II in the non-depressed and depressed groups were 3.89 (s.d. 3.55) and 20.28 (s.d. 6.68), respectively. Means and s.d. for BDI-II items in Finnish population are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Comparison of study populations from different countries

The mean scores of each symptom of BDI-II in different cultural populations are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The item ‘changes in sleep pattern’ (range 0.68–0.95) scored the highest in Finland, the Dominican Republic, Brazil and Mexico; ‘loss of energy’ (0.74) scored the highest in Norway; and ‘loss of interest in sex’ (0.91) scored the highest in Japan. ‘Suicidal thoughts’ (range 0.08–0.17) scored the lowest in every population. The item that scored the second lowest was ‘feelings of punishment’ in Finland and Norway (Finland: 0.11, Norway: 0.18), ‘worthlessness’ in Brazil and Mexico (Brazil: 0.27, Mexico: 0.16), ‘pessimism’ in the Dominican Republic (0.25) and ‘self-dislike’ in Japan (0.19).

The symptom items according to the BDI-II in six different cultural populations and the statistically significant differences between the populations are presented in Fig. 2. The Finnish population scored significantly lower in ‘indecisiveness’ (P = 0.034) and significantly higher in ‘changes in sleep pattern’ (P = 0.039) and ‘irritability’ (P = 0.019) than other populations. Compared with other populations, Norway scored significantly higher in ‘loss of pleasure’ (P = 0.033), the Dominican Republic scored significantly higher in ‘loss of interest’ (P = 0.009), Mexico scored significantly higher in ‘self-criticalness’ (P = 0.049) and ‘feelings of punishment’ (P = 0.048), and Japan scored significantly higher in ‘sadness’ (P = 0.013). The detailed results are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 2 Spider chart showing relative means of BDI-II items in different culture populations. Significant difference (P < 0.05) between all other countries and Finland (a), Norway (b), Dominican Republic (c), Mexico (d) and Japan (e). BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II.

Table 2 Results of meta-analysis including relative mean scores for each symptom in each country and meta-regression comparing the differences in the relative score of each symptom between each country separately

Figures marked in bold indicate statistically significant results.

a. Relative means score calculated by dividing the mean value of each symptom with the total mean and further divided by the number of Beck Depression Inventory-II items (item mean/(total mean/21)).

Discussion

We compared the BDI-II item scores in all currently available population-based samples from six different countries, and found significant differences in several item scores between them. In the Finnish population, the item ‘indecisiveness’ scored lower and items ‘changes in sleep pattern’ and ‘irritability’ scored higher than in other populations. The Japanese population had a significantly higher ‘sadness’ score, the Norwegian population had a higher ‘loss of pleasure’ score, the Mexican population had higher ‘self-criticalness’ and ‘feelings of punishment’ scores, and the Dominican Republic population reported significantly higher ‘loss of interest’ score than samples from the other countries. Thus, the findings of this study can increase awareness of the cultural differences in depressive symptoms and enable effective interpretation of the BDI-II item scores.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that conducted an item-by-item comparison of the BDI-II across different countries, with population-based samples. Consequently, the possibility of comparing our results with earlier studies is limited. When considering ethnicity and cultural background, no significant correlation between ethnicity (categorised as White versus other) and BDI-II total score was previously found.Reference Beck, Steer and Brown4,Reference Steer, Ball, Ranieri and Beck31 Some measurement invariance defined by ethnicity has been reported across groups.Reference Dere, Watters, Yu, Michael Bagby, Ryder and Harkness27,Reference Whisman, Judd, Whiteford and Gelhorn28 In addition, cultural differences in symptom reporting were revealed among Chinese-heritage and European-heritage undergraduates in North America, as Chinese-heritage students scored higher on cognitive symptoms of depression.Reference Dere, Watters, Yu, Michael Bagby, Ryder and Harkness27 In our study, Asia was only represented by Japan, which scored higher in the ‘sadness’ item, which is part of the general depression symptoms factor in the model presented by Ward.Reference Ward32

The original version of the BDI has previously been compared between European countries, and although it has been suggested to be a good tool for cross-cultural comparison, some differences in the relative weight of BDI items have been found between countries, especially regarding the Spanish sample, which placed greater importance on items ‘sadness’, ‘pessimism’ and ‘self-accusation’, and less importance on items ‘guilty feelings’, ‘indecisiveness’ and ‘loss of libido’. In addition, a Finnish sample placed greater importance on items ‘social withdraw’ and ‘body image’, and a British sample placed greater importance on items ‘fatigability’ and ‘weight loss’.Reference Nuevo, Dunn, Dowrick, Vázquez-Barquero, Casey and Dalgard19 In our study, the Dominican Republic and Mexico samples used the Spanish-language version of the BDI-II, and found similar results regarding the Mexican sample scoring higher than our other samples on the items ‘feelings of punishment’ and ‘self-criticalness’.

The probability of answering certain items of the BDI-II with low or high points may have been influenced by underlying cultural or language-version issues. This study was not focused on different language versions, but compared studies that used a translation of the BDI-II. Our study supports the previous recommendation that cultural context should be taken into better account when assessing issues of clinical psychology.Reference Ryder, Ban and Chentsova-Dutton33 We can only speculate on the clinical settings, but taking account that patients likely have culturally diverse background, the cultural background and the potential role of acculturation should also be acknowledged when interpreting the results of questionnaire and when choosing the language version the patient will answer.

The major strength of this study is that this is the first international, population-based, item-by-item comparison made for BDI-II. However, this study has some limitations, including the differences between the populations we compared. Not all of the study participants were recruited through random sampling. The study populations also differed by age, although most of them were focused on adults. We found differences in item scores from the two younger samples (Dominican Republic and Mexico), which could also be associated with the lower age of the participants. All of the studies used different translations instead of the original BDI-II, which may partly explain the differences between the study populations, as translations might slightly alter the meaning of items. It is also important to note that we only had data from six countries, so it is not possible to draw strong conclusions about cultural differences, and comparison based on larger data is needed in the future. Thus, there is a need to examine the underlying factors explaining the cultural differences in future studies, as cultural background might affect how people answer the questionnaire and thus impede the results.

In conclusion, we found distinct differences in BDI-II item scores distribution between different countries. Thus, the possible cultural or language differences should be considered when interpreting the BDI-II questionnaire scores or comparing the BDI-II scores cross-culturally, as failure to do so may impede findings.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.13

Data availability

NFBC data is available from the University of Oulu, Infrastructure for Population Studies. Permission to use the data can be applied for research purposes via the electronic material request portal. In the use of data, we follow the EU General Data Protection Regulation (679/2016) and Finnish Data Protection Act. The use of personal data is based on each participant's written informed consent at their latest follow-up study, which may cause limitations to its use. Please, contact the NFBC Project Center ([email protected]) and visit the cohort website (www.oulu.fi/nfbc) for more information.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the cohort members and researchers who participated in the 46-year study. We also acknowledge the work of the NFBC Project Center.

Author contributions

M.S., T.L., J.A., J.M., R.K. and M.T. contributed to study design. M.S. and J.M. were involved in the literature search and selection of the articles. M.S. and J.M. analysed the data. M.S., T.L., J.A., J.M., R.K. and M.T. were involved in data interpretation. M.S., T.L., J.A., J.M., R.K. and M.T. were involved in writing and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The NFBC received financial support from the University of Oulu (grant number 24000692), Oulu University Hospital (grant number 24301140) and European Regional Development Fund (grant number 539/2010 A31592). The study was financially supported by the Ministry of Education and Culture in Finland (grant numbers OKM/86/626/2014, OKM/43/626/2015, OKM/17/626/2016, OKM2017, OKM2018 and OKM2019), and Juho Vainio Foundation, Finland. The funders of the study did not have any role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.