Introduction

The past half-century has witnessed an unprecedented proliferation of corporate legal departments in the United States (Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007; Simmons and Dinnage Reference Simmons and Dinnage2011; Lipson Reference Lipson2012; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2012), driven by a variety of factors ranging from rising service cost to a shifting regulatory environment (Simmons and Dinnage Reference Simmons and Dinnage2011, 99–100; Glidden Reference Glidden2013, 134). This “in-house lawyer movement” has broad implications for the legal service market, the legal profession, and corporate governance (Chayes and Chayes Reference Chayes and Chayes1985; Gilson Reference Gilson1990; Lipson Reference Lipson2012; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2012). Seasoned in-house lawyers, for instance, alleviate the information asymmetry between companies and their outside law firms and therefore tilt the balance of power in favor of the former (Chayes and Chayes Reference Chayes and Chayes1985, 290; Gilson Reference Gilson1990, 902). Moreover, with professional training and discipline, in-house counsel are expected to uphold the ethical principles of their employers and “curb corporate opportunism” (Simmons and Dinnage Reference Simmons and Dinnage2011, 79), or, quite the opposite, to accommodate corporate misconduct if they yield to corrupt organizational forces (Rosen Reference Rosen2002, 1169–72; Kim Reference Kim2005, 997). While the topic has been explored from diverse perspectives (Chayes and Chayes Reference Chayes and Chayes1985; Roach Reference Roach1990; Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007; Simmons and Dinnage Reference Simmons and Dinnage2011; Barnes, Cully, and Schwarcz Reference Barnes, Cully and Schwarcz2012; Lipson Reference Lipson2012), only recently did researchers add an international angle to it by studying the worldwide diffusion of the in-house counsel movement (Kitagawa and Nottage Reference Kitagawa, Nottage, Alford, Chin, Cecere and Johnson2007; Liu Reference Liu2012; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2012; Garth Reference Garth2016; Wilkins and Khanna Reference Wilkins, Khanna, Wilkins, Khanna and Trubek2017; de Oliveira and Ramos Reference de Oliveira, Ramos, Cunha, Gabbay, Ghirardi, Trubek and Wilklins2018). This article takes a step further in that direction and investigates an increasingly important albeit underexplored topic—the in-house legal capacity of Chinese multinational companies operating in developed countries.

In the past decade, emerging market companies, especially those headquartered in China, have eroded the dominance of Western firms over the global flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) (Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Cross, Tan, Xin and Voss2008; Luo, Xue, and Han Reference Luo, Xue and Han2010; Cui and Jiang Reference Cui and Jiang2012; Peng Reference Peng2012), raising numerous practical, policy, and theoretical questions. For researchers of the legal profession, questions of particular interest include whether and how emerging market investors cultivate internal legal capacity to handle the complex and unfamiliar institutional environment of developed host countries, whether the in-house legal capacity exhibits any home-state characteristics, and whether state-owned companies figuring prominently in emerging market FDI—especially FDI from China—differ from privately owned firms in this regard. These questions, which should also interest practitioners and policy makers hoping to understand how the multinationals structure their investments in developed host countries, handle legal and compliance risks, and interact with local legal professionals, have not received adequate academic treatment.

This article attempts to narrow the gaps by analyzing the internal legal capacity of Chinese multinationals in the United States. The rest of the article proceeds as follows. The second section reviews the literature on the in-house counsel movement and accentuates its neglect of non-Western multinational companies, leaving a hole in our understanding of the legal service market and the legal profession in the globalization era. The neglected topic also bears on research about the adaptation of multinationals to host country legal and regulatory environment. The third section refines the conventional analytical frame by underscoring the diversity of corporate ownership structures and the multiplicity of institutional influences on Chinese multinationals in the United States. To provide readers with a necessary background, the first subsection of the third section traces the path of economic reforms taken by the Chinese Party-State, depicts the country’s state-business relations and institutional context, and recounts a hybrid in-house legal movement. Next, combining qualitative and quantitative data, the third section’s second subsection surveys the internal legal capacity of Chinese companies in the United States and then assesses the effects of state ownership on the employment of legal managers. The fourth section discusses the article’s contributions and makes several suggestions for future research. Last, the fifth section concludes the article.

LITERATURE ON THE IN-HOUSE COUNSEL MOVEMENT AND AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE LEGAL CAPACITY OF EMERGING MARKET MULTINATIONALS

The scholarship on the proliferation of in-house lawyers in the United States and their ascent in the corporate hierarchy has identified several key contributory factors (Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007; Simmons and Dinnage Reference Simmons and Dinnage2011; Lipson Reference Lipson2012; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2012). Among them, cost is deemed the most consequential. Concerns with rising legal service price have allegedly incentivized companies to internalize its production (Lipson Reference Lipson2012, 240; Glidden Reference Glidden2013, 134). Undergirding this cost-saving argument is the perennial question of corporate “making versus buying” (Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007, 523). According to Coase, all economic transactions should occur via spot contracts in a perfect market, and firm-organized production arises out of market imperfections (Coase Reference Coase1937, 42). This encompassing transaction cost theory, however, has been criticized for lacking predictive power—it is almost tautological to say that companies will hire in-house counsel and produce legal services internally whenever doing so costs less than purchasing the same services in the marketplace. In response to the critique, some scholars have sought to refine the theory. Williamson and others, for instance, contend that asset specificity and incomplete contracts engender opportunism that vertical integration may mitigate (Klein, Crawford, and Alchian Reference Klein, Crawford and Alchian1978; Williamson Reference Williamson1979). Focusing on information cost as a type of transaction cost, Alchian and Demsetz consider the organization of the firm as a result of varied shirking opportunities and monitoring needs (Alchian and Demsetz Reference Alchian and Demsetz1972). It is sometimes cheaper to transfer knowledge and information in the form of directions to employees (to make) than instructions to suppliers (to buy) (Demsetz Reference Demsetz1988).Footnote 1

Besides the firm-centered transaction cost theories, some scholars attribute the US in-house movement to the changing institutional environment. According to this institutional account, the transformation of certain US regulations prompted managers to adjust corporate compliance behavior and expand in-house legal capacity (Daly Reference Daly1997, 1061). For instance, changes in the Federal Sentencing Guidelines motivated companies to elevate the role of chief compliance officers and to ensure direct lines of reporting, usually to the board of directors, as those implicated in a criminal offense may avoid harsh legal penalties by showing an effective compliance program (Simmons and Dinnage Reference Simmons and Dinnage2011, 101).

Still another theoretical angle of inquiry focuses on the agency of in-house lawyers. Corporate in-house lawyers formed their own organizations and collectively made the case that inside counsel, with superior business knowledge and a long-term horizon, can better advise their corporate employers than outside lawyers (Rosen Reference Rosen1988; Nelson and Nielsen Reference Nelson and Nielsen2000; DeMott Reference DeMott2005; Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007).Footnote 2 The rising status of in-house counsel attracted first-rate lawyers to join their ranks, which further substantiated the claim of superior service (Glidden Reference Glidden2013, 135). Meanwhile, the scope of their work expanded. Apart from giving legal advice, in-house counsel typically oversee the hiring of outside lawyers and often participate in managing government relations and making key business decisions (Lipson Reference Lipson2012; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2012), thereby rendering their services indispensable to corporate employers.

These three strands of scholarship, centering respectively on transaction cost, regulatory institutions, and agency, have greatly advanced our understanding of the in-house movement in the United States. However, for analyzing the internal legal capacity of multinationals, especially those originating from China, the available theoretical tools require some retuning, as they share the same basic assumption that emphasizes profit-maximizing firms operating in a mature service market relatively free from arbitrary governmental intervention. Arguably, such an assumption only partially holds for Chinese multinational companies (MNCs) and those from most other developing countries. As will be elaborated in the following section, such MNCs typically survive and thrive in a domestic setting where institutions are still undergoing significant and frequent changes, and formal rules often succumb to informal ones. Also, governments in China and some other developing countries tend to play a highly interventionist role in corporate management and business transactions, as exemplified by direct state ownership in many of the largest Chinese MNCs (Cuervo-Cazurra et al. Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Inkpen, Musacchio and Ramaswamy2014). While state-owned enterprises (SOEs) may pursue commercial interests, profit maximization rarely counts as their primary goal (Bai et al. Reference Bai, Li, Tao and Wang2000). Furthermore, the vast majority of developing countries still feature a weak rule of law, loosely organized legal professions, and underdeveloped legal service markets.

Hence, research about Chinese MNCs calls for an analytical approach that assigns more weight to the multiplicity of institutional influences and the diversity of corporate ownership. First, MNCs are subject to the institutional influences of both the host state and the home state. While the internal legal capacity of multinationals has caught only limited scholarly attention (Miyazawa Reference Miyazawa1986; Daly Reference Daly1997), a vast literature exists on a related topic—the reactions of foreign persons to host country institutions (Mezias Reference Mezias2002; Yamazaki and Kayes Reference Yamazaki and Kayes2007; Salomon and Wu Reference Salomon and Wu2012; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Ding, Li and Zhang2014). Researchers generally agree that the behaviors of individuals and firms residing in a foreign country are susceptible to the dual influence of their home- and host-state institutions (Miyazawa Reference Miyazawa1986; Beechler and John Reference Beechler and John1994; Ferner Reference Ferner1997; Fisman and Miguel Reference Fisman and Miguel2007; Estrin et al. Reference Estrin, Meyer, Nielsen and Nielsen2016), which have been further categorized into informal institutions, formal institutions, and organizational governance (Estrin et al. Reference Estrin, Meyer, Nielsen and Nielsen2016, 296). Culturally grounded informal institutions, highly resistant to rapid changes (North Reference North1990; Williamson Reference Williamson2000, 597), may exert normative and cognitive influence on corporate legal capacity by shaping how people perceive the law and its role in management and business transactions (Holburn and Zelner Reference Holburn and Zelner2010, 1292–93). As multinationals usually assign expatriates to run their foreign affiliates, the informal institutions of the home states should continue to mold their decisions in the host countries (Meyer and Thein Reference Meyer and Thein2014, 158). Moreover, formal institutions of the home state have extraterritorial impacts. Many rules of MNCs’ home states, that is, the places of their principal business, restrain the foreign affiliates either directly (e.g., those concerning government approval of foreign direct investments) or indirectly (e.g., rules prohibiting money laundering, tax evasion, or foreign corrupt practices) (Cuervo-Cazurra Reference Cuervo-Cazurra2008, 635). Furthermore, corporate governance may channel home-state influence to MNCs’ foreign affiliates. The headquarters typically design internal rules to align employee conduct with company goals.Footnote 3 Such rules, inevitably echoing the MNCs’ home-state contexts, should alter the behavior of all their employees including those in developed host countries. In short, the legal capacity building of MNCs in developed host countries should be a function not only of the host country’s market and regulatory environments, but also of relevant home-state institutions.

Second, the in-house lawyer literature, focusing on profit-maximizing firms, has overlooked the complexity of state-owned MNCs. SOEs play a pivotal role in the expansion of emerging economies, especially China (Girma and Gong Reference Girma and Gong2008; Cui and Jiang Reference Cui and Jiang2012; Li, Cui, and Lu Reference Li, Cui and Lu2014; Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Clegg, Voss, Cross, Liu and Zheng2018). Though business entities worldwide may be converging in their forms and organizational structures (Hansmann and Kraakman Reference Hansmann and Kraakman2000, 454–55), significant variations remain across firms of different ownership types. For instance, after two decades of systematic reform, most SOEs in China have morphed into hybrid entities taking on the form of private companies and embracing profit seeking as a managerial object. At the same time, however, SOEs are tasked with implementing government policies, safeguarding national security, and enhancing social welfare (Huang, Li, and Lotspeich Reference Huang, Li and Lotspeich2010). This multitasking feature complicates both the SOEs’ organizational governance and their governmental control. On the one hand, SOEs react to market forces rewarding efficient firms, as the government assesses senior executives’ performance based partially on how well they preserve the market value of state assets (Hu and Leung Reference Hu and Leung2012, 259–60). Thus, state-owned multinationals should develop their internal legal capacity just as their local peers in developed host countries. On the other hand, SOEs yield to pressure from nonmarket institutions that motivate the managers to implement various government policies (Wang Reference Wang2014, 653–60). The nonmarket institutions may extend their influence abroad and shape the behavior of the foreign affiliates, including their internal legal capacity building.

To summarize, in researching the internal legal capacity of Chinese MNCs, researchers need to modify the existing theories on the in-house movement by assigning more analytical weight to the varying ownership structure of the MNCs and the dual influence of home-state and host-state contexts. The following section, which empirically examines the employment of legal managers by Chinese firms in the United States, will concentrate on these two underexplored aspects.

Chinese Multinationals in the UNITED States and Their Internal Legal Capacity Building

Four decades of meteoric growth catapulted China to its position as the largest emerging economy. With an enormous foreign currency reserve, the Chinese government conceived and implemented a “Going Out” policy aimed at spurring outbound foreign investment. While a large fraction of the subsequent capital outflow targets resource-rich developing countries, Chinese outbound investors increasingly venture into mature and competitive markets (Globerman and Shapiro Reference Globerman and Shapiro2009; Pietrobelli, Rabellotti, and Sanfilippo Reference Carlo, Rabellotti and Sanfilippo2011; Klossek, Linke, and Nippa Reference Klossek, Linke and Nippa2012; Li Reference Li2018). Against this backdrop, Chinese direct investment in the United States grew by 32 percent annually from 2010 to 2015, and in 2016 alone the investment doubled to $46 billion.Footnote 4 Given the enormous institutional gaps between the two countries, Chinese MNCs face daunting challenges in adapting to the intricate legal and regulatory environment of the host country (Zhang Reference Zhang2014; Li Reference Li2018). Worse yet, the escalating US-China confrontation, having recently triggered a reversal of China’s FDI trajectory, further heightened the Chinese investors’ legal and compliance risks in the United States. Do they develop internal legal capacity to cope with such risks, and if so, how? Does their employment of in-house counsel reflect any attribute of the home-state institutions? And does the investor’s ownership structure make a difference? These questions, despite their policy and theoretical significance, have thus far escaped systematic research. This section will explore them in two steps. The first subsection, Hybrid In-House Movement in China, briefly recounts China’s nascent in-house counsel movement driven by both top-down state pressure and bottom-up market forces. As noted above in the second section of the article, multinationals are subject to the institutional influence of both host states and home states, so the context for the in-house movement in China should cast a shadow over the internal legal capacity of Chinese investors in the United States. Next, the second subsection of this section, Chinese MNCs in the United States and Their In-House Counsel, draws on quantitative and qualitative evidence to evaluate the institutional effects.

Hybrid In-House Movement in China

Through a series of institutional engineering, the Chinese Party-State constructed a “Socialist market economy” that intermeshes business transactions with comprehensive state intervention. As a part of the reform, the government privatized most small- and medium-sized SOEs and allowed nonstate investors to hold the equity of many large SOEs (Guo Reference Guo2003, 557). Moreover, to “modernize” SOEs, the central government established the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), which serves as both the dominant shareholder and the regulator of the largest state-owned corporate groups in China.Footnote 5

While preserving a robust state sector, the economic reform also fortified the role of the market in allocating resources and buttressed fundamental market-enabling institutions such as laws safeguarding private property and courts capable of adjudicating complex commercial disputes. Also, to facilitate the economic liberalization, the government set up securities exchanges and the regulating institutions (Hua, Miesing, and Li Reference Hua, Miesing and Li2006, 403). Companies seeking to raise capital on the securities market must obtain government approval by meeting numerous organizational and performance standards (Li and Zhou Reference Li and Zhou2015, 77). In the past two decades, hundreds of Chinese companies have undergone drastic reorganizations and asset reallocations and thereby succeeded in trading their securities on domestic and foreign exchanges.

To the surprise of many observers, Chinese state capitalism has thrived (Bremmer Reference Bremmer2009; Lin and Milhaupt Reference Lin and Milhaupt2013; Milhaupt and Zheng Reference Milhaupt and Zheng2015; Wu Reference Wu2016). In 2019 China had more Fortune 500 companies than the United States, marking a “historic shift” in global business power, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) contributed more than 80 percent of Chinese companies on the list (Zheng Reference Zheng2019). In other words, government agencies at the central and regional level continue to assert control over many of China’s largest conglomerates that have become globally competitive (Ralston et al. Reference Ralston, Terpstra-Tong, Terpstra, Wang and Egri2006). Yet, contrary to conventional wisdom, the prominent state sector coexists with a rather dynamic private market. By the end of 2017, 93 million privately owned Chinese businesses employed approximately 340 million people, contributing more than 60 percent of China’s GDP growth and fixed-asset investment.Footnote 6 The country’s domestic stock exchanges now list 3,485 Chinese companies,Footnote 7 while by one estimate SOEs account for roughly 80 percent of the market capitalization (Peng et al. Reference Peng, Bruton, Stan and Huang2016, 298).

The rise of state capitalism foreshadows the hybrid in-house counsel movement in China. Akin to the other components of the massive socioeconomic transformation, the in-house movement comprises both a top-down state-driven process and a bottom-up market-driven process. The former refers to measures taken by government agencies to enhance corporate in-house legal capacity, the latter the economic and regulatory factors motivating firms to develop internal legal capacity. The following two subsections recount these top-down and bottom-up processes respectively.

State-Driven In-House Movement

Despite the systematic market reform, the Chinese Party-State continues to rely heavily on SOEs to implement its policies, raise revenues, and maintain social control (Naughton and Tsai Reference Naughton and Tsai2015, 9–10). The government realizes its domination over SOEs by, among other things, retaining the power to make major personnel and management decisions for the companies (Leutert Reference Leutert2018, 1–2). Top SOE executives are evaluated periodically by their corresponding supervisory government bodies (Lin and Milhaupt Reference Lin and Milhaupt2013, 738–43). Due to the state control, profit maximization is rarely the primary, or even a prioritized, goal for SOE managers (Bai, Lu, and Tao Reference Bai, Lu and Tao2006; Estrin et al. Reference Estrin, Meyer, Nielsen and Nielsen2016). This multitasking feature of Chinese SOEs complicates their management of risks, including legal risks.

The state control also spawns an acute multi-agency problem (Mi and Wang Reference Mi and Wang2001; Bruton et al. Reference Bruton, Peng, Ahlstrom, Stan and Xu2015; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Bruton, Stan and Huang2016). While the separation of management and ownership characterizes all modern corporations, the misalignment of interests tends to be more severe in Chinese SOEs, as their managers answer to multiple layers of supervising bodies. The chain of agency relationships extends to the top CCP leadership, and the interest mismatch manifests at all levels. The complex agency problem begets suboptimal responses to corporate legal risks. On the one hand, SOE managers whose interests are imperfectly aligned with those of the shareholders discount losses from the companies’ illegal acts and therefore may underinvest in diagnostic and preventive measures such as employing competent in-house counsel. On the other hand, SOE managers may overinvest in mitigating legal risks as cost savings generate no immediate personal benefits, whereas salient breaches of law may reach the public domain and jeopardize their careers. Despite the predictive ambivalence, Chinese SOEs historically underinvested in internal legal capacity (Liu Reference Liu2012, 565; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2012, 286), as their political power shields the directors and managers from legal risks (He and Su Reference He and Su2013; Jia, Mao, and Yuan Reference Jia, Mao and Yuan2019).

However, once the central government clearly signaled its preference for SOEs to expand in-house legal departments, the managers responded promptly. The top-down campaign was jump-started by a “palace war” between SASAC’s institutional predecessors and the Ministry of Justice to implement two vastly different models of in-house legal departments (Liu Reference Liu2012, 558). Eventually, SASAC proved a more effective and resourceful executor. Exemplifying a typical policy implementation in an authoritarian state, SASAC designed three-year plans to boost the internal legal capacity of all SOEs under its supervision. In 2004, SASAC promulgated Measures for the Administration of In-House Legal Counsels of State-Owned Enterprises, giving detailed instructions on developing internal legal capacity.Footnote 8 SOEs were urged to employ full-time legal advisors to safeguard state assets. SASAC also attempted to elevate the status of legal counsel within the corporate hierarchy—the 2004 Measures clearly stipulated that chief legal officers be members of the senior executive team.Footnote 9 Additionally, the agency designed metrics to assess progress, and in doing so it repeatedly looked to Western firms for benchmarks (Zhou Reference Zhou2015). The stated goals of the campaign, for instance, include attaining the average ratio of in-house legal staff to total employees at MNCs from advanced economies and ensuring that one-third of the central SOEs would “become world leaders in this regard.”Footnote 10

The top-down in-house movement gained more momentum after the 18th CCP Congress in late 2013 initiated a concerted push to “build a rule-of-law China” (Dong Reference Dong, Ye, Li and Wu2014, 64). To implement this party policy, SASAC announced a five-year plan (following the consecutive three-year plans) to further expand the internal legal capacity of SOEs.Footnote 11 As a result of these efforts, in-house positions at Chinese SOEs tripled from seven thousand in 2005 to twenty-one thousand in 2016 (Zhou Reference Zhou2015),Footnote 12 and all of the 102 central corporate groups under direct SASAC supervision have established the requisite system of chief legal officers.Footnote 13

The remarkable progress on paper and in numbers, however, is veneer for the many remaining problems with the corporate legal departments of Chinese SOEs. As the top-down approach relies on observable and measurable factors, the unmeasurable aspects of legal risk have been neglected. For instance, the competency of the legal staff, crucial to providing high-quality services (Tao Reference Tao2016, 45), has not improved nearly as much as the size of the in-house legal departments would indicate (Dong Reference Dong, Ye, Li and Wu2014; You Reference You, Ye, Li and Wu2015). Although SASAC permitted open recruitments of chief legal officers, some SOEs either had senior executives retain top in-house legal posts concurrently or assigned unqualified managers to those positions (Zhai Reference Zhai2017). Therefore, it is not unusual for nonlawyers to be chief legal officers of Chinese SOEs (Zhai Reference Zhai2017). Moreover, structural relegation of legal officer roles to low status and poor compensation also contribute to the nonprofessional staffing of the legal departments (Ma Reference Ma2013; Zhai Reference Zhai2017).Footnote 14 According to one estimate, merely 20 percent of the in-house legal staff at Chinese SOEs have passed the national bar examination (Ma Reference Ma2015a). Nor has the SASAC campaign substantially boosted the authority of in-house counsel. Although SASAC stipulates that chief legal advisors should be allowed to participate in all major corporate decisions, senior executives often attribute little or no consideration to such involvement, resulting in the tangential role of the legal departments (Chen Reference Chen and Ye2015b; Ma Reference Ma2015b; Zhang Reference Zhang2016). As noted by a Chinese lawyer who was once the general counsel of a central level SOE, the position is merely for “staging.”Footnote 15

Market-Driven In-House Movement

Extensive as it is, the authority of SASAC and its regional counterparts is limited to SOEs and their affiliates. In other words, the top-down in-house movement is constrained mainly to the public sector. By contrast, market forces propel the nascent expansion of legal departments at private Chinese companies. The bottom-up in-house movement had a humble beginning. Much of China’s economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s was made possible by entrepreneurs constantly ignoring or disobeying preexisting rules designed to perfect a Soviet-style planned economy (Li, Feng, and Jiang Reference Li, Feng and Jiang2006). Widespread grassroots noncompliance created opportunities for reform-minded political elites to nurture a budding market economy (Ang Reference Ang2016). This reformist mentality, however, ossified into a corporate culture of disrespect for formal rules and rampant noncompliance (Jian Reference Jian2017; Li Reference Li2018). A weak judiciary, plus robust informal institutions, further marginalized the role of Chinese law in private business transactions (Zhang and Li Reference Zhang and Li2017).

It is, therefore, no surprise that in-house legal staff are generally confined to a low status in the corporate hierarchy (Jian Reference Jian2017, 277), and the majority are not qualified to practice law (Ma Reference Ma2015b). As observed by a seasoned in-house lawyer, general counsel in China often spend more than half of their time on nonlegal work (Jian Reference Jian2017). Nonetheless, a market-driven in-house movement has begun to gain speed. Formal law has become relatively more important in commercially developed regions and in transactions between parties of political and economic parity (He Reference He2012; Li Reference Li2017b). Hence, some private companies have learned to take rules more seriously (Yan and Ding Reference Yan, Ding, Ye, Li and Wu2014; Li Reference Li2018). For instance, China-based MNCs such as Alibaba employ hundreds of in-house lawyers, and its general counsel occupies a top executive position (Wilkins Reference Wilkins2012, 288; Jian Reference Jian2017, 262). Like their US counterparts, some Chinese in-house lawyers recently began to extend their sphere of influence beyond managing corporate legal risks by participating in policy and lawmaking (Yan and Ding Reference Yan, Ding, Ye, Li and Wu2014, 89).

In summary, two sets of institutional forces have propelled a nascent in-house counsel movement in China. The top-down pressure from the state led to the rapid expansion of legal departments in Chinese SOEs, and the bottom-up market forces incentivized some large private firms to foster internal legal capacity. As previously discussed, the institutional influence may reach abroad and shape the internal legal capacity building of Chinese multinationals in the United States. First, home-state institutions exert normative and cognitive influence on the managers of Chinese MNCs’ foreign affiliates (Holburn and Zelner Reference Holburn and Zelner2010; Meyer and Thein Reference Meyer and Thein2014). The relatively low status of in-house counsel in China and the peripheral role of law in business transactions may affect how the managers running the US operations weigh the importance of internal legal capacity. Second, the set of institutions governing SOEs should have regulative effect on their US investments. The control of the Chinese government over state-owned MNCs does not end at the national border, as the headquarters in China typically retain the power to make major personnel decisions concerning top-level and sometimes even mid-level managers of the US affiliates (Li Reference Li2018, 76). In addition, SASAC and its peers have promulgated increasingly complex rules to curb the discretion of SOE managers. Due to the extraterritorial, hierarchical control, the set of institutions governing Chinese SOEs can modify the corporate behavior of their US affiliates, including their internal legal capacity building.

Chinese MNCs in the United States and Their In-House Counsel

To briefly recapitulate, the worldwide expansion of Chinese MNCs raises vital questions that the existing scholarship on in-house lawyers, having concentrated on privately owned companies in mature domestic markets, has neglected. A step forward necessitates widening the inquisitive lens to incorporate the multi-institutional influences over MNCs and their varied ownership structures. From this refined perspective, and combining quantitative and qualitative methods, the rest of the subsection analyzes the employment of full-time in-house legal managers by Chinese MNCs in the United States.

The quantitative analysis relies primarily on a set of comprehensive survey data collected in 2019 through a collaboration with the China General Chamber of Commerce USA (CGCC), by far the largest business association of Chinese companies in the United States.Footnote 16 The survey questionnaires were sent to about 600 CGCC members, fielding 247 respondents—a response rate of approximately 41 percent. A comparison between the CGCC members and all Chinese firms registered with the Ministry of Commerce to have made direct US investment indicates an overrepresentation of large companies and SOEs in the CGCC sample,Footnote 17 which serves well the purposes of this study.Footnote 18

The qualitative evidence comprises information derived from 122 interviews with business executives, in-house counsel, lawyers, and consultants employed by Chinese companies in the United States.Footnote 19 The interviews were collected through multisource snowball sampling. Personal acquaintances, that is, friends and former colleagues working for Chinese MNCs in the United States, constitute one core group of the interview subjects. They shared valuable insights and introduced me to more interviewees. Another cohort comprises CGCC members, some of whom also tapped into their personal and business networks for possible research subjects. Additionally, some interviews were conducted at various panels, workshops, and conferences on law and foreign investment.Footnote 20 The multisource snowball method generated a sample of professionals with diverse backgrounds (see Table 3 in Appendix for more details).

The empirical findings are presented in two parts. The first subsection below offers an overview of the internal legal capacity of Chinese MNCs in the United States, which I contend clearly evinces the influence of the home-state institutions. The next subsection statistically tests the intercompany variations of the in-house capacity, with the spotlight on the effects of Chinese investors’ ownership structure.

Varying Internal Legal Capacity of Chinese MNCs

The term “internal legal capacity” is broad. This study centers on the key aspect of it—the employment of full-time staff managing corporate legal matters. In assessing this variable, the survey presents the respondents with three choices: (1) having a full-time in-house legal manager licensed to practice US law, (2) having a full-time in-house legal manager not licensed to practice US law, or (3) having no full-time in-house legal manager. Had the Chinese MNCs reacted exclusively to the US institutional environment, the data should show that all in-house counsel are legal professionals (Nelson and Nielsen Reference Nelson and Nielsen2000; Wilkins and Khanna Reference Wilkins, Khanna, Wilkins, Khanna and Trubek2017, 121). But if, as this article posits, the home-state institutions continue to shape the acts of Chinese MNCs in the United States, one should observe nonlegal professionals employed as full-time legal managers, which remains a common practice in China.Footnote 21

As shown in Figure 1, the majority (56.9 percent) of the Chinese companies surveyed do not retain full-time in-house legal managers. Cost analysis appears to be a major factor. Many Chinese companies, having recently ventured into the competitive US market, have devoted their attention and resources to cultivating a niche clientele, for example, businesses with extensive exposure to China (Li Reference Li2018, 38). Without a steady stream of repetitive legal matters, such companies consider the employment of full-time counsel to be wasteful. One respondent, an executive of a large Chinese SOE, dismissed the idea of hiring a full-time internal lawyer as too expensive, regardless of the company’s capacity to afford such hiring, and unnecessary, since the firm’s current US operations do not give rise to many legal problems.Footnote 22 Even incremental rise of legal service demand does not necessarily result in the hiring of full-time in-house counsel, as less costly means such as a retainer arrangement are easily available. By paying a fixed retainer fee, typically a fraction of the salary for professional in-house counsel, Chinese investors ensure timely legal service, and such arrangements are usually made with outside lawyers familiar with their businesses. According to the CEO of a Chinese-invested business, his company keeps a lawyer on retainer because it has only a few lawsuits a year and conducts mostly standardized transactions.Footnote 23 Apart from the cost-based calculus, lack of legal risk awareness also explains the absence of in-house counsel at some Chinese firms. An experienced lawyer describes Chinese investors as “headless flies” with “shocking ignorance of US law.”Footnote 24 Another lawyer echoes the observation, noting, “Chinese managers don’t respect rules, so they find the US market full of landmines.”Footnote 25 Some investors even manage their US businesses “as if they were Chinese domestic subsidiaries.”Footnote 26

FIGURE 1. Full-Time Legal Manager at Chinese Companies in the United States.

Meanwhile, 43.1 percent of Chinese companies have employed full-time legal managers in the United States. Again, cost-based calculation plays a key role. According to the interviews, some Chinese executives engage in the conventional “making versus buying” analysis. For the companies with substantial US investments, high demand for repeated legal services justifies the internalization of their production. At the same time, major attributes of the corporate culture, organizational structure, and management style of Chinese companies are foreign to US lawyers who, in order to provide high-quality service, would need to acquire the specific knowledge. This “asset specificity” typically induces mutual dependence, opportunism, and consequently vertical integration (Williamson Reference Williamson1979; Rosen Reference Rosen1988; Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007). US lawyers normally lack a strong incentive to accumulate firm-specific knowledge of Chinese corporate clients, as they generally do not constitute a significant revenue source.Footnote 27 An in-house counsel of a Chinese company with substantial US investments commented that most US lawyers lack requisite knowledge about Chinese businesses, yet at the same time Chinese managers, new to the US market, are oblivious about potential legal and regulatory issues. His company decided to hire an in-house lawyer after learning that lesson from several costly setbacks.Footnote 28 Another executive interviewee observed that, in comparison to local peers, Chinese firms tend to encounter more intricate legal issues and therefore are in acute need of tailored legal advice. Hence, the company recruited a former outside lawyer, a Chinese licensed to practice in both China and New York, as its general counsel.Footnote 29 Additionally, in cases where a US lawyer has acquired firm-specific knowledge, the Chinese corporate client would become highly dependent on the services. During one of the interviews, the in-house lawyer of a Chinese MNC’s New York subsidiary complained about the occasional overbilling of its outside law firm, yet she took no action. “The firm has been working with us for years. We don’t want to offend the senior partner [who overbilled], as it’s hard for us to switch.”Footnote 30 Such costly reliance further incentivizes Chinese MNCs to internalize the production of US legal services (Gilson Reference Gilson1990, 899).

Significantly, 8.5 percent of Chinese companies have employed full-time legal managers unlicensed to practice US law, evidencing the multi-institutional influence. Had Chinese investors responded solely to the US context, none would have hired a layperson to manage US legal matters. By contrast, nonlawyers often lead corporate legal departments in China. Apparently, the institutions of both the host state and the home state shape the legal capacity building of MNCs (Holburn and Zelner Reference Holburn and Zelner2010, 1292–93). As noted earlier, home-state institutional influence may materialize in multiple ways. First, Chinese MNCs feel regulatory pressure from Beijing. SASAC stimulated a top-down in-house counsel expansion, and the agency’s influence extends beyond the Chinese border. In other words, state-owned Chinese companies may have nonlawyers direct the US legal department simply to satisfy the SASAC requirements. According to the chief legal officer of a Chinse SOE’s US subsidiary, he got the position largely because the headquarters in Beijing trusted him. Though he initially declined the offer, citing lack of any legal training, the management insisted.Footnote 31 When asked why the company had to establish such a position if a “trustworthy” legal professional was unavailable in the United States, he pointed out that the position was “required by SASAC.”Footnote 32 Second, normative and cognitive pressure may also play a role. Managers in China, treating law as a peripheral matter, often consider professional in-house staff dispensable. Given the mindset, Chinese MNCs in the United States may be reluctant to invest in high-quality in-house legal service. “They took US law seriously only after ‘paying a heavy tuition.’”Footnote 33 Third, internal organizational control is relevant. Chinese MNCs may expatriate nonlawyer executives to oversee legal matters in the United States as a natural extension of the parent’s governance structure. Given the strategic significance of the US market, the Chinese headquarters feel a strong need to assign a trusted person to lead the legal department, and that trusted person is more likely to be a Chinese executive not licensed to practice US law. As will be discussed, this is especially true for state-owned Chinese investors that tend to assert tight control over their US operations.

To summarize, the descriptive survey data present a snapshot of the internal legal capacity of Chinese multinationals in the United States, and the interviews offer preliminary explanations about the intercompany variations of this capacity. The following subsection will further examine the variations.

Varying Internal Legal Capacity

To test the legal capacity variation, I create a categorical dependent variable corresponding with the three scenarios in the survey question: (1) a Chinese company does not have a full-time manager of US legal matters; (2) the company has a full-time legal manager, but he or she does not have a license to practice US law; (3) the company has a full-time legal manager and he or she is a qualified US lawyer. Scenario (1) serves as the baseline, and the question to be investigated is why some Chinese MNCs in the US deviate from it by hiring either US lawyers or non-US lawyers to manage their legal matters.

As discussed earlier, scholars have explored the US in-house movement from three theoretical perspectives: transaction cost, regulatory context, and the agency of in-house lawyers. The subsection on Varying Internal Legal Capacity of Chinese MNCs above clearly illustrates that for understanding the internal legal capacity of Chinese multinationals it is crucial to broaden the analytical scope by incorporating the effects of home-state institutions and state ownership. Through this more inclusive theoretical lens, this subsection conducts further analysis of the legal capacity variations revealed by the survey data.

The analysis will give special attention to the effects of the investors’ ownership structure, which characterizes Chinese MNCs and has spawned heated debates. As previously discussed, SASAC retains extensive control over most of the Chinese conglomerates. The agency, in order to boost SOEs’ legal capacity, set measurable goals such as reaching certain percentages of full-time in-house counsel. In response, “many central SOEs adopted a top-down model by first creating a whole [in-house legal] frame and then extending it to their subsidiaries” (Lin Reference Lin and Ye2015). Consequently, the size of the in-house legal staff grew rapidly, yet nonlegal professionals have filled many of the positions (Ma Reference Ma2013; Zhai Reference Zhai2017).

As state-owned Chinese MNCs venture overseas, the top-down pressure to expand in-house legal departments diffuses to their foreign affiliates. Note that, due to the limit of SASAC authority, private Chinese companies are not susceptible to the top-down pressure. Therefore, the ownership character of Chinese investors may influence their employment of full-time legal managers in the United States. To be more concrete, some Chinese headquarters appoint lay people to lead US legal departments partially to satisfy relevant SASAC requirements.Footnote 34 In the words of an experienced Chinese lawyer, nothing but the governmental pressure led to such “staging” behavior.Footnote 35 Hence, I hypothesize that Chinese companies with state ownership would be more likely to have full-time staff in charge of legal matters who are not licensed to practice US law.

Less straightforward is the tie between a Chinese investor’s state ownership and the employment of professional in-house counsel. As noted earlier, managerial risk aversion and agentic discount of cost saving generate conflicting predictions about SOEs’ investment in legal capacity. That said, for the same reasons SOEs fill the legal director positions with nonlawyers in China, I adopt the working hypothesis that state-owned Chinese investors are less likely to employ professional legal managers in the United States.

To statistically assess the independent variable of interest—state ownership—a dummy variable is created from the survey data and assigned the value of one if a Chinese government entity owns more than 50 percent of the Chinese investor’s equity interest, and zero otherwise. Majority ownership affords the home state clear legal control over the US investments. In some circumstances, however, a state owner may exert substantial influence without being the majority shareholder, for example, significant minority shareholders in companies featuring dispersed ownership (Milhaupt and Zheng Reference Milhaupt and Zheng2015). Hence, I also create an alternative state-ownership measure that equals one if a Chinese government body owns more than 10 percent of a Chinese investor, and zero otherwise.

Moreover, the theories extrapolated from the existing literature suggest several other variables as possible explanations for the varied in-house legal manager attributes (Table 1). As discussed earlier, scholars adopting the transaction cost view would predict that companies with substantial business internalize legal service production as they encounter frequent and repetitive legal issues (Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007, 516; Coates et al. Reference Coates, DeStefano, Nanda and Wilkins2011, 240). Moreover, companies running large US operations also have more complex legal and corporate issues that constitute a steep learning curve for outside lawyers (Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007). Bringing lawyers in-house may reduce the education cost usually born by the clients. In other words, asset specificity, another typical attribute of large businesses, engenders potential opportunism in corporation–outside counsel relationships that will be alleviated by internalizing legal service production. In short, economies of scale and complex firm-specific information, both of which characterize sizable US operations, are conducive to the employment of full-time legal staff. In testing this conventional argument, I use two variables to approximate the size of US operations. The first one is US business revenue reported by the responding Chinese companies. The survey subjects chose one of five levels of revenue, with the lowest level being “below one million dollars” and the highest level “above 100 million dollars.”Footnote 36 The second measure of business size is the number of employees in the United States reported by the surveyed Chinese companies.

I also include additional variables that account for the potential influence of relevant host country institutions. As discussed in the second section, some scholars ascribe the US in-house legal movement to changing regulatory environment (Simmons and Dinnage Reference Simmons and Dinnage2011, 99–105). Companies in heavily regulated sectors tend to have repeated and complex legal and regulatory issues and therefore are more likely to hire full-time in-house counsel to manage those risks. Moreover, in-house legal departments bear “primary, though not exclusive, responsibility for compliance efforts” undertaken by large US corporations (Chayes and Chayes Reference Chayes and Chayes1985, 287). Hence, it is arguable that companies operating in heavily regulated sectors with onerous compliance burdens be more likely to cultivate internal legal capacity. The same logic may apply to foreign-based MNCs in the United States. For instance, prior research on Japanese MNCs contends that the decision to employ in-house US lawyers hinges on the type of business and the disputes arising therefrom (Miyazawa Reference Miyazawa1986; Kitagawa and Nottage Reference Kitagawa, Nottage, Alford, Chin, Cecere and Johnson2007). In the same vein, sectoral regulation may associate with the internal legal capacity of Chinese companies in the United States. According to the manager of a Chinese firm operating in the financial sector, which is extensively regulated at both the federal and the state level, a third of the firm’s US staff were hired to handle compliance and legal matters.Footnote 37 That is much higher than the average ratio of legal to total employees at commercial banks in China (Chen Reference Chen and Ye2015a, 60). To account for the possible effect of the host-state institution, I add sectoral regulation to the tests. I collect the data for this variable from the regulation intensity index compiled by McLaughlin and his colleagues. Each of the survey respondents is assigned to an industry designated by a two-digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code, which corresponds to a regulatory intensity index number.Footnote 38

Another variable that falls under the regulatory environment frame is Chinese MNCs’ listing status. As discussed above in the subsection on Hybrid In-House Movement in China, securities markets in China and elsewhere facilitated the reform by “modernizing” and “Westernizing” Chinese companies (Chen, Firth, and Rui Reference Chen, Firth and Rui2006; Steinfeld Reference Steinfeld2010). Many SOEs and private Chinese companies large enough to make US investments have listed their stocks on major exchanges in China and abroad. The listing status may be relevant for several reasons. First, the additional oversight by securities regulators magnifies US legal risks for publicly traded companies. For instance, both the Chinese and the US securities regulations mandate the disclosure of major lawsuits that will have “a material effect” on the share price of a listed company.Footnote 39 Such disclosure may generate more transaction and compliance costs for public companies. Second, mandatory disclosures of this type—which are intended to inform the market of the potential level of legal risk—have a negative and costly impact on the capital market that can be difficult to control for a public company, and prior research has recorded share price fluctuations following such disclosures (Griffin, Grundfest, and Perino Reference Griffin, Grundfest and Perino2004, 25). Although the Chinese capital market is still evolving, it nonetheless responds to the disclosures of major legal and regulatory risks (Yu, Guo, and Kang Reference Yu, Guo and Kang2014, 137–38). In short, Chinese companies listed on the stock exchanges, falling under extra market and regulatory oversight, may take legal risks more seriously than other Chinese firms. A question in the survey inquired about the listing status of the responding firm’s managing entity. From the data, a dummy is created and assigned the value of one if a Chinese business in the United States is managed by a listed company, zero otherwise. Moreover, one may reasonably argue that listing on a US stock exchange is materially different from having securities traded in other commercial centers such as Shanghai, as the former is subject to more rigorous regulation and enforcement, and US law elevates corporate legal officers’ gatekeeping role in public companies (Kim Reference Kim2005, 997). Accordingly, I create an alternative listing status dummy that equals one if a Chinese investor is listed in the United States, zero otherwise.

Additionally, the mode of Chinese investment in the United States may also have an effect on the intercompany variations of the internal legal capacity. Presumably, if a Chinese MNC expands into the United States by acquiring an established local company, the workforce may be subject to less institutional effect from China (Tan and Mahoney Reference Tan and Mahoney2006, 475). I use two dummy variables gleaned from the survey data to evaluate this hypothesis. The first dummy equals one if a Chinese MNC entered the US market via a merger or an acquisition or by forming a joint venture, zero otherwise. Such an entry mode arguably facilitates localization and adaptation (Ahmed et al. Reference Ahmed, Mohamad, Tan and Johnson2002; Cui and Jiang Reference Cui and Jiang2009). An executive interviewee noted that her company acquired a US firm located in New York City and kept the entire workforce, including the in-house legal team. The Chinese headquarters only sent one person, the interviewee herself, to oversee the US operations.Footnote 40 As a result, the US affiliate operates just like a local company. For some of the Chinese MNCs, however, entry mode does not fully account for the extent of localization. They may begin by setting up a representative office or a small business in the United States to survey the market and identify potential acquisition targets, and large-scale mergers or acquisitions may not occur until years after their initial entry. Also, a merger or acquisition agreement typically fixes a time limit on the retention of a target company’s management team. Therefore, I create another dummy variable that equals one if a responding firm has engaged in a merger or acquisition in the past two years, zero otherwise.

Furthermore, the tests also include investment duration as a control, as the length of time a Chinese MNC has operated in the United States may be associated with both the investors’ ownership structure and their employment of internal legal counsel. According to a recent study, state-owned Chinese investors are generally more responsive to home-state policies, so their US investments might coincide with the government’s “Going Out” policy (Li Reference Li2018, 91). Moreover, recent Chinese investors and their predecessors tend to occupy different sectors. In the few years leading up to 2019, Chinese FDI in the United States spanned a wide range of businesses, whereas earlier the investments were more concentrated in trade. Miyazawa’s study of Japanese companies in the United States suggests that those specializing in trade tend toward employment of non-US lawyers as legal managers (Miyazawa Reference Miyazawa1986). Adding the variable of investment duration will help to control for potential temporal factors relating to the legal service preference.

Table 1. Summary Statistics

Source: 2019 CGCC Annual Membership Survey.

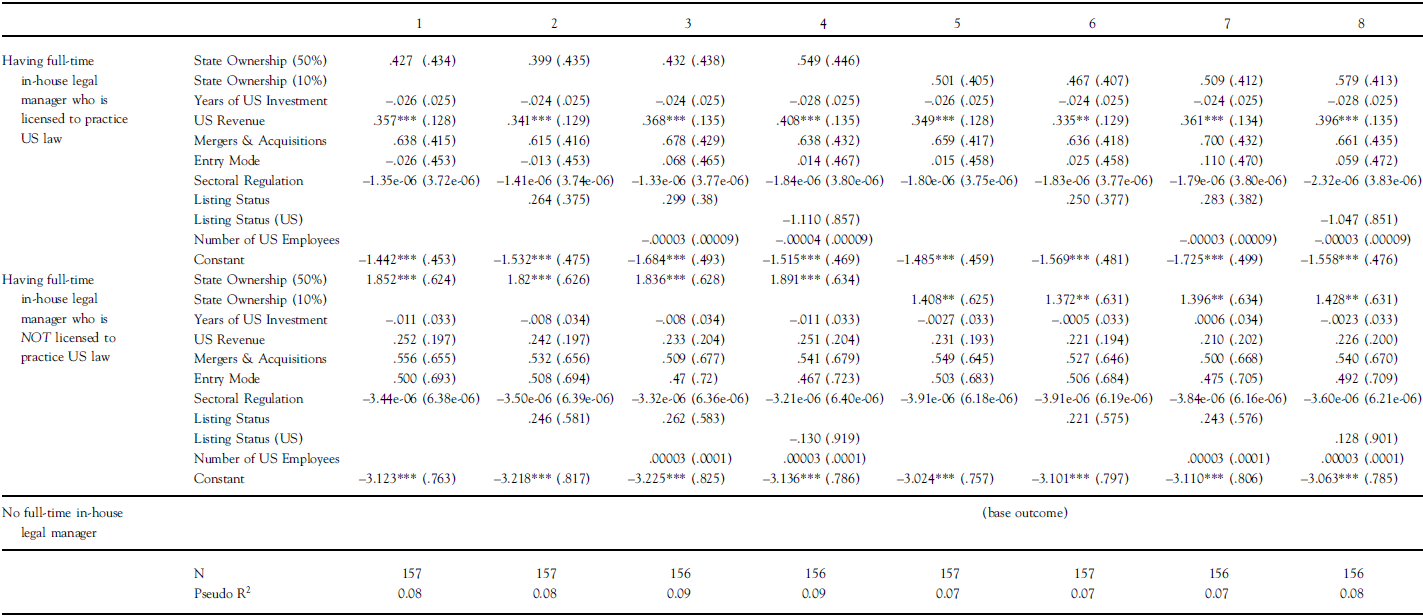

Because the dependent variable consists of three nominal categories, I run a series of multinomial logistic regression tests to assess the hypothetical associations articulated above. Table 2 below list the results from various model specifications, with the scenario of “no full-time legal manager” as the baseline. Because the effect of Chinese MNCs’ ownership structure is the key independent variable of interest, the tests all revolve around it. Four of the models use the 50 percent state-ownership dummy, and the other four employ the alternative dummy of 10 percent state ownership.Footnote 41

Table 2. Regression Results

Notes: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.5, ***p < 0.01.

State ownership

The test results confirm the hypothetical link between state ownership of Chinese investors and the employment of non-US lawyers as legal managers in the United States. To be more concrete, when other factors such as the size of US operations, investment duration, and listing status are held constant, state-owned Chinese multinationals are more likely than private Chinese investors to have full-time non-US lawyers to manage their US legal matters. The finding, highly significant and robust across all the model specifications, further confirms the influence of the rules of relevant home-state institutions such as SASAC on state-owned Chinese investors in the United States, channeled through hierarchical corporate control and regulative extraterritoriality. Recently SASAC, in reaction to several high-profile outbound investment failures involving Chinese SOEs, began to emphasize the mitigation of overseas legal and compliance risks.Footnote 42 Consequently, among all the metrics used to assess SOE managers, those relating to corporate legal capacity have been foregrounded. The top-down pressure has translated into more superficial compliance by state-owned Chinese MNCs in the United States.

Meanwhile, state-owned Chinese MNCs are not significantly different from their privately owned counterparts in hiring professional legal managers when the other variables are controlled for. One may interpret the lack of significance as evidence that SOEs respond to market forces, so when business needs justify the internalization of legal service production, Chinese MNCs, regardless of their ownership type, will hire professionals to get the work done. However, given the sample size, anything more than a preliminary inference awaits future research.

Size of US operations

In line with the existing literature, the US revenue of the Chinese MNCs is significantly associated with the employment of US legal professionals as in-house legal managers. To be concrete, with all the other variables such as investment duration and ownership structure held constant, Chinese MNCs with larger US businesses are more likely to employ US lawyers to manage their US legal matters. And the finding is robust across all the model specifications. As is well documented in prior research, companies with substantial operations inevitably encounter a steady flow of repetitive legal matters that are cost-effectively dealt with by in-house lawyers. Also, Chinese MNCs with large operations tend to confront complex and firm-specific legal issues unfamiliar to US lawyers. Meanwhile, US law firms, few of which rely heavily on Chinese clients as a main source of revenue,Footnote 43 find little incentive to accumulate such client-specific knowledge necessary for high-quality diagnostic and preventive services crucial to managing long-term legal risks (Gilson Reference Gilson1990, 893). Bringing US lawyers in-house will help to mitigate this problem.

Unsurprisingly, size of US operations is not significantly associated with the hiring of non-US lawyers as full-time legal managers. Once the influence of the SASAC rules and other home-state institutions is insulated, the MNC managers’ cost-based calculus cannot reasonably lead to the employment of lay people to manage complicated US legal matters.Footnote 44 Again, the interpretation, consistent with the existing literature, can be further buttressed by findings of nonsignificance from testing larger samples.

Merger and acquisition

This variable is weakly associated with the employment of US lawyers as in-house legal managers, and the significance is found in several of the eight model specifications.Footnote 45 As previously discussed, the mode of investment may influence the extent to which Chinese MNCs localize their US operations. Chinese investors that recently engaged in a merger or acquisition tend to be more adaptive to the host country’s institutional contexts as they typically retain the management team of the target companies, including the in-house lawyers. Take Lenovo as another example. After the Chinese MNC acquired IBM’s PC business, it set up a US headquarters and expatriated only a few senior executives. The US operations have been run like a local business ever since the acquisition (Li Reference Li2018, 26). The variable has no significant connection with the hiring of nonprofessional managers. Though inconclusive, this intuitive finding indirectly evinces the effects of the home-state institutions such as the SASAC rules and the underlying extraterritorial state control.

As Table 2 shows, none of the other variables such as listing status and entry mode is significant. However, given the size of the sample in this study, more definitive conclusions of their irrelevance to Chinese MNCs’ internal legal capacity await future empirical research.

Contributions and Suggestions for Future Research

This article makes several theoretical and policy contributions. First, it adds to the scholarship on the in-house counsel movement. To date, much of the research has been premised on profit-maximizing firms operating under market forces and an increasingly complex regulatory environment, either domestic or foreign (Schwarcz Reference Schwarcz2007; Simmons and Dinnage Reference Simmons and Dinnage2011; Barnes, Cully, and Schwarcz Reference Barnes, Cully and Schwarcz2012; Lipson Reference Lipson2012; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2012; Wilkins and Papa Reference Wilkins and Papa2013; Wilkins and Khanna Reference Wilkins, Khanna, Wilkins, Khanna and Trubek2017; de Oliveira and Ramos Reference de Oliveira, Ramos, Cunha, Gabbay, Ghirardi, Trubek and Wilklins2018). By examining the experience of Chinese MNCs in the United States, this article takes the crucial first step in a long-term endeavor to explore the legal capacity of MNCs, especially those from developing countries that are assuming a growing role in the global economic order. The study delineates the mechanisms through which the Chinese government has compelled SOEs to develop internal legal capacity. And the top-down pressure, according to the empirical findings, extends beyond the national border and impacts how SOEs’ foreign affiliates cope with local legal risks. In particular, state-owned Chinese MNCs are prone to employing non-US lawyers to manage US legal matters. At the same time, the article finds evidence confirming the extant literature. All else being equal, larger Chinese businesses in the United States are more likely to hire professional in-house legal managers.

Second, the article contributes to the vast literature on international business, which has traditionally focused on MNCs from developed countries. While nascent scholarship explores emerging market MNCs (Rui and Yip Reference Rui and Yip2008; Luo and Rui Reference Luo and Rui2009; Barnard Reference Barnard2010; Knoerich Reference Knoerich2010; Luo, Xue, and Han Reference Luo, Xue and Han2010; Sauvant, McAllister, and Maschek Reference Sauvant, McAllister and Maschek2010; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Boateng2012; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Luo, Lu, Sun and Maksimov2014; Xia et al. Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2014), only a very few studies have touched on their capacity to adapt to the sophisticated legal and regulatory systems of developed host countries (Zhang Reference Zhang2014; Li Reference Li2018). To narrow the gap, this article investigates a critical component of that adaptive capacity—corporate legal managers—and seeks to draw out the factors shaping its development. The article helps to explain how developing country MNCs attempt to overcome the liability of foreignness, particularly in the legal and regulatory ground, and will assist in understanding their internalization of service production in other areas such as accounting and human resource management (Smith and Zheng Reference Smith, Zheng, Liu and Smith2016; Ouyang et al. Reference Ouyang, Liu, Chen, Li and Qin2019). The findings also underscore the tension between the institutional influence of the home state and the pressure the Chinese MNCs endure in the host state. The tension, if not managed properly, has dire practical consequences. Take SANY (a large China-based multinational manufacturing heavy machinery) as an illustrative example. Without professional in-house counsel participating in key management decisions, the company failed to consider the national security implications of a substantial US investment that ultimately led to forced divestiture (Li Reference Li2017a, 8). Likewise, the New York branch of Agricultural Bank of China disregarded grave US legal and compliance risks that resulted in a severe penalty of $215 million (Matthews Reference Matthews2016).

Third, the empirical findings shed light on research about the evolving legal service market. The minority of Chinese firms that employ non-US lawyers as legal managers are unable to rectify the information asymmetry when dealing with outside lawyers. Anecdotal evidence indicates that some Chinese law firms have expanded abroad to fill the gap by serving as “outside general counsel” for Chinese MNCs.Footnote 46 They establish satellite offices in commercial hubs such as New York City and Los Angeles, recruit US lawyers with extensive Chinese backgrounds, and connect their clients with local legal service providers.Footnote 47 Future research on this phenomenon will add to the emerging literature on the globalization of law firms, especially those headquartered in developing countries (Liu Reference Liu2008; Wilkins and Papa Reference Wilkins and Papa2013; Li Reference Li2019).

Fourth, this article highlights the impacts of globalization on the in-house counsel movement in China (Wilkins and Khanna Reference Wilkins, Khanna, Cunha, Gabbay, Ghirardi, Trubek and Wilklins2018). In-house legal departments were initially established in late 1970s and early 1980s by Chinese SOEs trading internationally (Zhou Reference Zhou2015). Growing exposure to foreign legal risks led to heavy losses, forcing them to react by enhancing internal legal capacity (Guo Reference Guo2017; Shaffer and Gao Reference Shaffer and Gao2018, 163). Moreover, SASAC has been using MNCs based in developed countries as benchmarks for advancing in-house legal departments in Chinese SOEs (You Reference You, Ye, Li and Wu2015; Zhou Reference Zhou2015). For instance, China Coal Group, one of the largest central SOEs, selected three large MNCs in the coal industry—two US-based, and one headquartered in Switzerland—for an extensive comparative study and found “major gaps” such as “disparities in compliance culture and legal management concept” (Zhou Reference Zhou and Ye2014, 140). The study then urged Chinese SOEs to “learn from large European and US companies,” and implored the government to make rules that would strengthen the authority of in-house counsel (Zhou Reference Zhou and Ye2014, 144). Furthermore, foreign companies investing in China tend to establish professional in-house legal departments, offering a role model for domestic Chinese companies to imitate. Future research should explore more systematically this dynamic aspect of the transnational legal ordering (Halliday and Shaffer Reference Halliday and Shaffer2015; Shaffer Reference Shaffer2016).

Fifth, the employment by Chinese MNCs of nonlawyers as legal managers in the United States clearly implicates their attorney-client privilege. The application of the privilege rules is complex, and much of it turns on factual analysis. Nonetheless, the key legal conditions are well established, and the most important one for claiming attorney-client privilege by a corporate client over communications with in-house counsel is that “the person to whom the communication is made [must be] a member of the bar of a court.”Footnote 48 Those Chinese MNCs hiring nonlawyer legal managers in the US risk inadvertent forfeiture of the privilege, unnecessary litigation costs, and reputational damage from the disclosure of otherwise privileged materials.

Apparently, the study leaves open some key questions to be investigated in future research. First, what demographic factors help us to define these legal managers? Are they expatriated from China or recruited locally? Second, what are the typical roles of these lawyers? Do they, like their counterparts at US companies, participate in major management decisions? Third, to what extent do Chinese managers defer to in-house counsel? Are they as marginalized as their colleagues in China, or can they veto transactions burdened with substantial legal risk in the United States? Fourth, how do Chinese MNCs in the United States compare with MNCs from other countries and local companies regarding in-house legal capacity? Anecdotal evidence suggests that some Chinese MNCs, due to their “liability of foreignness,” may overcompensate and invest more than their local peers in managing US legal risks.Footnote 49 In regard to these questions, extensive, rigorous empirical research is needed before we can orient a path toward any decisive conclusion.

Conclusion

The past few decades have witnessed an expansion of in-house legal departments both in the United States and abroad. The existing literature on the subject, however, has focused on profit-maximizing firms operating in a mature and competitive service market. The global expansion of MNCs from China poses novel and important questions calling for a modified analytical framework that accommodates ownership diversity and institutional multiplicity. Taking a step in that direction, this article empirically examines the internal legal capacity of Chinese MNCs in the United States. It finds that some Chinese MNCs employ non-US lawyers as legal managers. Further analysis reveals that state-owned Chinese MNCs are prone to having nonprofessionals hold the position, and in contrast, Chinese MNCs with large US operations or recent mergers or acquisitions tend to employ US lawyers as legal managers. The findings have several theoretical and policy implications and chart the course for future research about the in-house counsel of MNCs from China and other emerging economies.

Appendix

Table 3. Background of Interviewees

Table 4. State Ownership and Legal Manager Attributes