Background

The World Health Organisation recommends that the multiple facets of healthcare should be appropriately understood before making any healthcare interventions (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2004). Despite a growing need to engage in health- and health systems-related research, there is still limited evidence of theoretical and methodological underpinnings about qualitative design in this area (Green and Thorogood, Reference Green and Thorogood2014).

Patton (Reference Patton2002) suggested that qualitative methods in primary healthcare (PHC) research would be appropriate to meet the needs and interests of decision-makers and healthcare practitioners by providing an in-depth understanding of complex health problems, which ultimately would be useful in health planning and management. In the same vein, Morse agreed that ‘qualitative [approaches] often address broad and complex problems rather than the concise hypotheses found in quantitative’ designs (Reference Morse2003: 834). In Green and Thorogood’s (Reference Green and Thorogood2014: xiv) view, one of the limitations of current approaches to generating qualitative evidence for PHC research is a lack of relevant and appropriate study design, as ‘the context of health research may be rather different from that of general social research’. To address these concerns, and add to the literature on health research, this paper uses qualitative-driven mixed method to explore the effects of decentralisation on provision of PHC services in the context of Nepal.

Methods

Setting

Nepal is one of the poorest countries of South Asia. Despite expanding the universal healthcare services through PHC settings to the rural communities, difficult topography (hills and mountains) and political instability have meant that Nepal has consistency failed to achieve a lasting change in improving people’s health status. Accessing and utilising essential PHC, mainly for poor and marginalised people, remains a challenge. Revitalisation of PHC, through improving health access, reducing health inequities, and addressing new challenges and expectations by ensuring high quality, has been put forward as an immediate agenda of the government (Department of Health Services, 2014).

Between 2007 and 2010, I conducted study on decentralisation, a system which involves the transfer of central governments’ resources with authority, accountability and responsibility to local tiers of government. Imbued in the notion of decentralisation is the belief that local is better in terms of identifying, analysing and implementing appropriate government actions (Regmi et al., Reference Regmi2010). Over four decades, decentralisation has been adapted to reform health services across the globe, and Nepal has also adopted this approach to reform its PHC services.

There is, however, little exploration concerning the impact of decentralisation policy on health service performance, mainly due to the complex nature of the subject matter, as well as methodological challenges. Qualitative design in health research can assist in filling this gap.

Methodological justification

Although there are no clear-cut divisions between quantitative and qualitative paradigms, and they are not mutually exclusive; quantitative research provides a more generalised and numerically based view of reality, allegedly neglecting social and cultural meanings (Patton, Reference Patton2002; Silverman, Reference Silverman2010). Broadly conceived, qualitative methodology encompasses a variety of methods, which are characteristically language-based, descriptive rather than analytical, and which, to varying degrees, recognise the experience of the researcher as a significant variable in the form of the data collected (Seale et al., Reference Seale, Giampietro, Jaber and David2004).

Flick (Reference Flick1998: 4) emphasised that ‘recognition and analysis of different perspectives, researchers’ reflections on their research as part of the process of knowledge production, and the range of approaches and methodology’ are important aspects of qualitative research. Qualitative methods, therefore, would be a preferred method for research design ‘when little is known about the topic, when research context is poorly understood, when the boundaries of the domain are ill-defined, when the phenomenon is not quantifiable, [or] when the nature of the problem is murky’ (Morse, Reference Morse2003: 833).

Based on the above criteria, qualitative methodology is a good fit for the present study. First, there have been some attempts to measure the impact of decentralisation through allocation of public expenses and revenues (fiscal decentralisation) using quantitative attributes (Porcelli, Reference Porcelli2009; Jiménez-Rubio, Reference Jiménez-Rubio2011) approaches would present a great challenge. According to Bossert (Reference Bossert2014), measuring decentralisation is more about who gets more choice (deconcentration or devolution), and how much choice (narrow, moderate or broad) is given to local authorities over what functions (financing, service delivery, human resources, access rules and governance), rather than an association of independent and dependent variables or causal relationships. This is mainly due to two challenges: (i) problematic concept, as different disciplines (political science, social policy, management, development studies, geography) use the term decentralisation and it appears in different conceptual literatures (federalism, central–local relations, principal–agent theory, public choice theory). Therefore, the concept of decentralisation is difficult to measure and link to the conceptual literature (Peckham et al., Reference Peckham, Exworthy, Powell and Greener2006). And (ii) methodological problem, as there is limited evidence available ‘that developed systematic definitions, conceptual frameworks and consistent methodologies to produce consistent, valid and reliable results’ (Bossert, Reference Bossert1996: 149). In addition, the nature of decentralisation is context-specific and is often multi-dimensional, therefore it has been suggested that the effects of decentralisation, even within a country, would be different (Litvack et al.,Reference Litvack, Ahmad and Bird1998).

Second, measuring the impact of decentralisation is a complex phenomenon, as health systems across the world are constantly changing, and how radically the change departs from past practice can often be difficult to measure in quantitative attributes (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2004). Third, the meaning and interpretation of decentralisation is ill-defined and it is recommended to understand its meaning through utilising stakeholders’ knowledge within their context, mechanisms, and expected outcomes (Pawson and Tilly, Reference Pawson and Tilly1997). Finally, evaluating the impact of health services, mainly in low- and middle-income countries, is often difficult due to the lack of reliable data systems, and traditional (quantitative) research may no longer be appropriate for addressing complex PHC interventions (World Health Organization, 2014).

Techniques, tools and approaches

The meaning and interpretations of mixed methods are debatable and this often creates some confusion over the way the term has been used in the research literature or paradigms. Cheek et al. (Reference Cheema and Rondinelli2015) argue that people often used the terms ‘mixed methods’, ‘mixed method research’ and ‘multiple methods’ interchangeably. In fact, these terms do not have the same meanings. Several authors argue that the term ‘mixed methods’ has consistently brought ambiguity, confusions and lack of precision (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Onwuegbuzie and Turner2007; Hesse-Biber, Reference Hesse-Biber and Johnson2010; Hesse-Biber and Johnson, Reference Hesse-Biber2013; Morse and Cheek, Reference Morse and Cheek2014; Cheek et al., Reference Cheema and Rondinelli2015). Greene (Reference Greene2006) warns that one of the challenges of using mixed methods research is not only the meaning and interpretation of qualitative and quantitative, but also the fact that they belong to different and incompatible paradigms. In such a context, Morse and Niehaus pose a question on ‘how researcher combines the qualitative and quantitative components in a single project as an essential consideration if rigour is to be maintained’ (Reference Morse and Niehaus2009: 19). It can be argued that the issue of incompatibility in mixed methods is always debatable, either due to the disciplinary devaluation of the qualitative component (Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Shope, Plano Clark and Green2006) or devaluation of anything less than experimental designs (Denzin and Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln2005). Another practical challenge is that there is no specific tool or technique that would be able to measure or evaluate the impact of mixed methods designs precisely (Morse and Niehaus, Reference Morse and Niehaus2009). Some commentators have questioned whether using both qualitative and quantitative criteria would be the best approach to evaluating the mixed methods (Sale and Brazil, Reference Sale and Brazil2004), but others see the validity ‘legitimation’ is the critical component beyond the sum of its parts (Onwuegbuzie and Johnson, Reference Onwuegbuzie and Johnson2006).

Generally, mixed methods are considered as a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods that were mixed, but here we have clearly seen the complexity and difficulty involved in the combination. According to Morse and Niehaus (Reference Morse and Niehaus2009), a mixed methods study ‘consists of a qualitative or quantitative core component and a supplementary component (which consists of qualitative or quantitative research strategies but is not a complete study in itself)’. This design would also consider ‘mix[ing] two qualitative methods or two quantitative methods’ (Morse and Niehaus, Reference Morse and Niehaus2009: 20). It is interesting to emphasise that the notion of mixed methods is not only mixing two or more approaches or their parts in a single study, but also ‘it is the point of interface of those approaches and the consequent integration of the results of the various components in the research … such integration is the key in mixed designs, both to the design and to the significance of the study’ (Morse and Cheek, Reference Morse and Cheek2015: 731).

Due to different theoretical drives, that is, the conceptual direction or overall purpose of the research, as well as a combination of both core and supplementary components, qualitative-driven mixed methods can possibly be categorised into four designs (Table 1).

Table 1 Qualitative-driven mixed method designs

Source: Adapted from Morse and Niehaus (Reference Morse and Niehaus2009: 25)

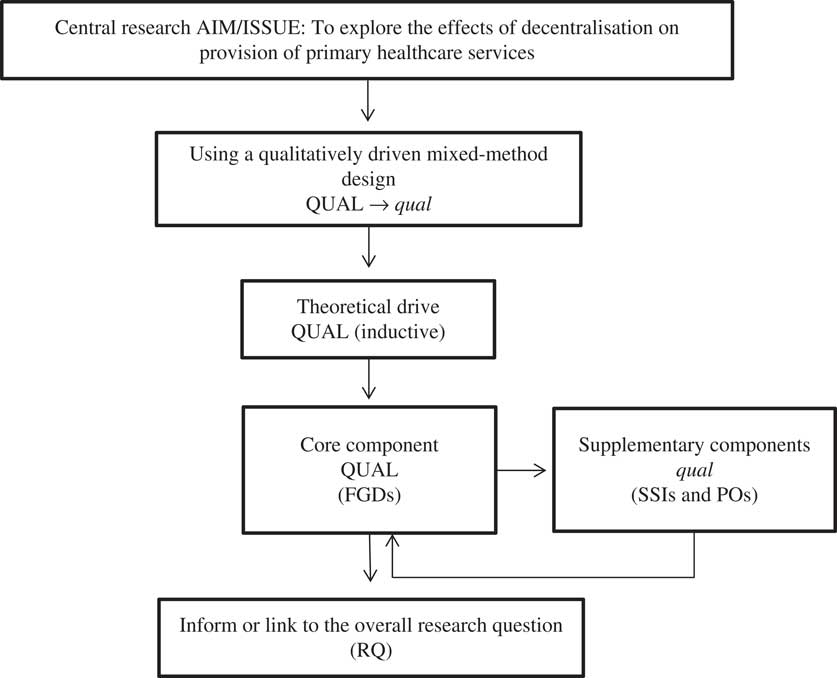

Given the objectives and significance of the study, I decided to adopt a qualitative-driven mixed methods design QUAL→qual. The study design, adapted from Morse and Niehaus’s (Reference Morse and Niehaus2009) qualitative-driven mixed methods research, has been represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Research design. FGDs=focus group discussions; SSIs=semi-structured interviews; POs=participant observations

I obtained data through three methods of data collections: focus group discussions (FGDs), semi-structured interviews (SSIs) and participant observations (POs), where the QUAL core component was the FGDs and the supplementary components were SSIs and POs. These were conducted sequentially, not only to obtain two different perspectives on the same phenomenon, but also to integrate the supplementary findings with the core component. From the SSIs, I hoped to understand the individuals’ perspectives and perceptions; from the POs, I wanted to contextualise the relationship between stakeholders; and from the FGDs, I hoped to see the participants’ knowledge and perspectives (perceptions, beliefs, experience), and some degree of inter-relationships. Morgan (Reference Morgan1998) and Phillips et al. (Reference Phillips, Dwan, Hepworth, Pearce and Hall2014) argued that one of the advantages of using multiple methods with multiple groups is that it allows a comparison of similarities. Additionally, according to Morse and Niehaus, ‘each qualitative method has particular questions that it may answer better than other qualitative methods’ (Reference Morse and Niehaus2009: 111).

In sum, as set out above, this research was mainly focussed on the collection of qualitative information, adopting an exploratory and interpretative approach to investigate a particular phenomenon, related to the decentralisation of health services in Nepal. The data were collected through FGDs, SSIs and POs, engaging myself in the research via an iterative process (Chambers, Reference Chambers1997).

Issues of sampling

The quality of research is often determined by the use of appropriate methodology, field instruments and suitability of the sampling strategy (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Manion and Morrison2011). This research utilised a purposive sampling method. As Teddlie and Yu (Reference Teddlie and Yu2007) and Bowling (Reference Bowling2009) discuss, a purposive sample is one of the non-random methods which is often used to obtain samples from a group of people, or a setting to be able to achieve representativeness, focussing on specific and unique issues or cases as well as generating a theory though collecting data from different sources. In this study, the process of recruitment (sampling) stopped when data saturation occurred and all concepts were generated (Ritchie and Lewis, Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003; Bowling and Ebrahim, Reference Bowling and Ebrahim2005).

Sample frames were used to recruit service users, service providers and members of the management committee. Bowling (Reference Bowling2009) notes that a sampling frame is a complete list of people or members from which the sample has been drawn. In this study, I utilised three registers, that is, patients, staff register and management committee, while recruiting those respondents purposively in order to represent the full range of demographical variables, for example, age, gender, professional (doctor, nurse). Mason (Reference Mason2002: 121) argues that while conducting qualitative research, researchers are perhaps ‘not interested in the census view, or trying to conduct a broad sweep of everything, so much as focusing in one specific issue, process, phenomenon, and so on’, as qualitative research is all about the ‘depth, nuance and complexity, and understanding how these work in reality’. As Newell (Reference Newell1996) argues, the selection of an appropriate sample frame also increases reliability, because the samples will be more likely to reflect the defined population accurately if selected again by using the same method.

Data collection

Focus groups

Hennink (Reference Hennink2007) and Silverman (Reference Silverman2010) argued that the purpose of having group discussions is to capitalise on communication between the group members to generate data. Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to provide insights to the subject matter (Campbell and Holland, Reference Campbell and Holland1999; Hennink, Reference Hennink2007). Questions covered in the focus groups included the effect of decentralisation on health services, and how specific groups perceived the decentralisation of health service implementation and management in their area. To gather information, I conducted seven FGDs: four with health service providers (HSPs) and three with district health service management committees (comprising individuals with political involvement, local leaders and representatives from excluded and marginalised communities). Each focus group contained four to six individuals who were selected purposively.

Interviews

I conducted SSIs, employing interview guides derived from both theories and drew upon previous research studies about the topic (Bossert, Reference Bossert2000; Bossert and Beauvais, Reference Bossert and Beauvais2002; Collins and Omar, Reference Collins and Omar2003; Omar et al., Reference Omar2007). To ensure cross-case comparability, a SSI protocol was deemed more convenient than an unstructured one. The broader issue of decentralisation was divided into the issues representing the health system and quality of health services; for instance, on the issue of decision-making, questions were asked as to how decisions about health services were taken, who made the decisions, who was involved, and how they communicated with other health service users (HSUs). This breakdown was intended to simplify the issue to make respondents feel comfortable in responding.

From a selection of 20 respondents, approximately five service users per study site from four PHC facilities were selected purposively, using the following general criteria to gain the widest representation:

-

∙ Geographical location of service users

-

∙ Caste and ethnic origin

-

∙ Wealth (these categories were developed with the help of health professionals and committee members of health service management)

-

∙ Sex (both male and female)

All interviews were tape-recorded after getting the respondents’ approval. Participants’ anonymity and confidentiality were protected throughout the study.

Field visits and POs

Mason (Reference Mason2002) argues that observation helps to generate data through the immersion of the researcher into the research context. I had ample opportunities to observe and participate in local events during my stay in the field, which helped me to understand local realities, behavioural patterns, culture and values. I took notes of each event, such as: what went well and why; what did not go well and why not? These data helped me to cross-check my research. In this study, I used more than one method of data collection (triangulation of the data) using FGDs and SSIs, field observation and reflective notes, involving different stakeholders to produce rich and detailed contextual findings. Such findings have not only explained the richer understanding of the same phenomenon – decentralisation of PHC – better, but also increase the validity and trustworthiness of the information by cross-checking different stakeholders’ viewpoints (Denzin, Reference Denzin1978; O’Cathain et al., Reference O’Cathain, Murphy and Nicholl2008; Green and Thorogood, Reference Green and Thorogood2014). Tylor and Bogdan (Reference Tylor and Bogdan1998) discussed that in PO, the researcher needs to go deeper into the sociocultural setting of the community for an extended period, and make regular observations of behaviour and the pattern of decision-making in social areas, such as participation, decision-making, culture, norms and values. During the field research, I had some opportunities to live within the community so as to interact with its residents, asking open-ended questions based on the situational context to get respondents’ unique views towards the local health services (Gray, Reference Gray2004). In the community, I also took part in meetings and discussions about local concerns, contributing ideas and sharing my own experience and knowledge about particular issues with other members. I recorded my observations and reflections regarding these meetings in a field notebook.

Data analysis

Data were collected from FGDs, SSIs and POs of different stakeholders in the study area. With the consent of the study respondents, events in relation to field studies were recorded in a field notebook. Answers from the interviews were recorded using a digital voice recorder and then transcribed/translated. This information entailed the aspects of service access, utilisation and delivery, including the understanding and perceptions of respondents about decentralisation linked to health services performance.

The analysis of my qualitative interviews and discussions began at the start of the interview process. In this research, I decided to undertake a basic content analysis of the qualitative data (Denzin and Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln1998; Patton, Reference Patton2002). A qualitative content analysis method searched for underlying themes in the text material, which contained information contributing to the theme of the research (Bowling and Ebrahim, Reference Bowling and Ebrahim2005). The analysis used transcripts of the FGDs and SSIs, identifying key concepts and allocating codes to them. Using NVivo10, codes and sentences were grouped and compared according to concepts and themes.

Issues of validity and reliability

Validity, reliability and generalisability are often linked with authenticity and robustness of any research or research findings (Regmi, Reference Regmi, Naidoo, Greer and Pilkington2013). The degree of accuracy of the description of the phenomenon depends upon the subject, and the context of the study reflects the meaning of validity (Bryman, Reference Bryman2001; Gray, Reference Gray2004). To attain validity and reliability, I adopted Mays and Pope’s (Reference Mays and Pope1996) criteria: first, I produced a thorough and comprehensive account of the phenomenon under scrutiny; second, I carried out my field analysis in such a way that another researcher could, in theory, analyse the data and draw comparable conclusions. As mentioned, I triangulated the data by utilising more than one method of data collection (FGDs, SSIs and POs). In addition, I cross-validated the data by sending some transcribed versions of the transcripts back to the respondents to ask whether my interpretations were accurate (Robson, Reference Robson1993). They agreed that the transcripts were a true reflection of records.

To further ensure the degree of validity and reliability, I followed a consistent approach in data collection, recording and documentation. First, I examined the stability of observations over time. I conducted FGDs and SSIs with different people in different times and places. Second, I employed inter-rater reliability (Denzin and Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln1994) via checks utilising two independent bilingual translators.

Results

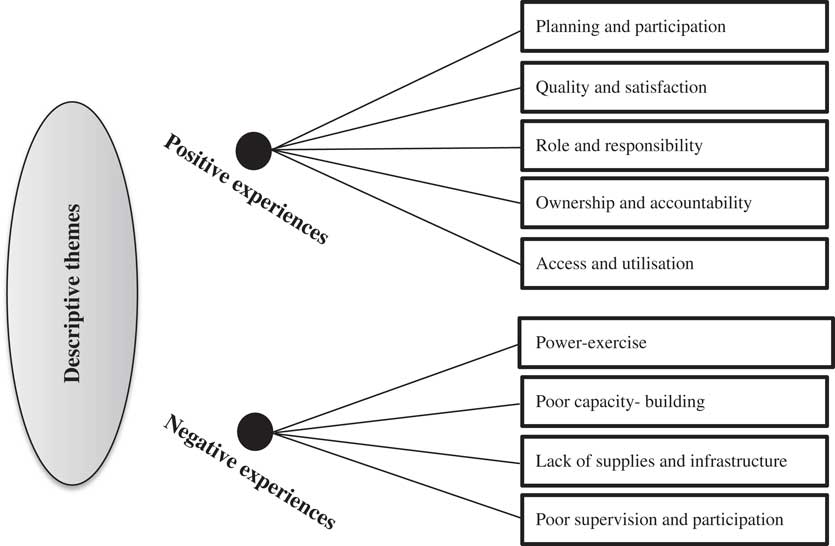

Four FGDs with HSPs (n=20), three FGDs with district stakeholders (n=15), SSIs with HSUs (n=20) and SSIs with national stakeholders (n=20) were carried out. Respondents were aged between 16 and 64 years with the mean age 40 years. Interviews took an average of 1.5 h and no one refused to be interviewed. The analysis allowed me to obtain 248 computer-generated NVivo10 nodes, which were related to the different dimensions of decentralisation and its impact on district health services, as well as the aspects affecting the decentralisation process. Two data coders were involved in this study. From this analysis it was possible to obtain two broad categories: positive and negative aspects of decentralisation related to access, quality, planning, supplies, coordination and supervision, and participation of PHC services at local levels (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Final lists of descriptive themes

Positive experiences

Planning and participation

It was clear that participants on the whole were involved in the planning and participation in the services their local health systems offered. Several respondents stated that they now accessed/utilised the local health services more than before in the community, and they also reported that local residents were more aware about their health and well-being. This perspective was reflected by both national stakeholders (policy-planners and decision-makers) and recipients of services interviewed in the study. For example, a health policy-planner stated, ‘There were some initiations of bottom-up health planning involving all stakeholders; people have now more developed their ownership’ (50-year-old male, national stakeholder). A member of a health management committee said, ‘Services are delivered from the village level, as if you develop the village-based programme, they will have more knowledge about their problems and concerns so that it would be much easier to solve them. [A b]ottom-up approach – will help to assess and identify local problems’ (45-year-old male, district stakeholder). On the same topic, another respondent stated his view:

Yes, I have been involved in planning and conducting of outreach clinic (ORC) clinics in the village several times as [a] community health volunteer. People recognise us well, giving more value so I feel more honour. (37-year-old female, HSP)

Quality and satisfaction

With reference to the quality of and satisfaction with the services they received, several respondents provided positive feedback. A female patient described her positive experience while visiting local health services:

I got the service on the same day that I asked for. Health professionals are very appropriate to resolve most of my own and family problems, and they are very friendly – easily approachable. (45-year-old female, HSU)

A male patient highlighted that the healthcare service he got was very good and very memorable, as he described he was there almost two weeks ago with the problem of snake bite. When he reached the PHC, the health professionals put his leg in colour water (potassium permanganate) for 12 h. Initially he thought that he would die, but in fact he got fantastic care from them as they were like his god (16-year-old male, HSU).

Yet, another female patient stated:

Offered very [good] quality services and health workers often requested follow-up visits; very good indeed as compared to 5–7 years ago. Always full numbers of health workers delivered health services from newly-constructed buildings; there were five beds for the in-patients, free services, [and an] ambulance for the referral/emergency cases. Good investigation and treatment facilities with friendly care; I liked it. (25-year-old female, HSU)

Participants on the whole noted the improvement of services from years past, which contributed to their satisfaction level.

Role and responsibility clarity

Several respondents noted that because they had more clarity about the roles and responsibilities of central and local governments in terms of accountability and resource allocations, local health plans could be developed and implemented more inclusively. Local health policies and procedures were now in place and, therefore, systems were more proactive in being guided by the needs and experience of local people. One district stakeholder, for example, reported:

[There] is now better coordination between [the] District Development Committee and District Health Office in terms of planning and resource-sharing (funds); as a result there [are] some improvements on patients’ attendance. (64-year-old male, district stakeholder)

Ownership and accountability

Several service providers noted that decentralisation would bring developed community ownership. The local medical director/healthcare in-charge, for example, described his positive experience and feeling about the community ownership and accountability:

Decentralisation has provided some space to health workers for making healthcare decisions. Because the local authority is an independent entity, we are now able to devolve or generate some revenues at [a] local level. As a result, local people, including political parties, are more accountable to health programmes, which was never the case in the past. (40-year-old male, HSP; 32-year-old male, HSP; 36-year-old female, HSP)

Developing and implementing health services based on local needs fostered more accountability on the part of the consumer.

Access and utilisation

Some respondents noted that local health policies or programmes were made based on their (users’) needs and experience (people-centred health services), and essential services were available at the local level. A female patient said:

Easy to come and get it and most of the services [are] completely free. Poor people who can’t afford private clinic can access these services without any costs. We are very happy. Medicines are available throughout the year. (34-year-old female, HSU)

A male patient stated the increased availability of basic medicines throughout the year. He added:

And they are much cheaper even if we required purchasing. Even x-rays and lab facilities exist in the village that made our life much easier, both cost- and time-wise. (28-year-old male, HSU)

Negative experiences

Power-exercise

Despite the aforementioned positive experiences, there were several concerns about decentralisation raised by study participants. One such concern involved collaboration power-sharing. One national stakeholder, for example, forcefully pointed out that though decentralisation is considered to be a fairer governance system, ‘political representatives often reflected their parties’ vested interests at a local level; as a result they often make decisions based on their interests. Sectoral operational working/service plans, particularly the monitoring and auditing, were not clearly defined’ (48-year-old male, national stakeholder). It is important that in decentralisation, collaboration is crucial between central and local governments, and even at the central Ministry of Health and Ministry of Local Development levels, and that needs to be clearly laid out. There are still, however, some issues which appear with regard to the role and responsibilities – who does what and who has what at the central and local health levels. Power-exercise was mostly used at central levels. The same sentiments were also shared by other study participants, that power-sharing has jeopardised role identification and clarification, both at the strategic and operational levels, in terms of planning and execution of healthcare at the local levels.

Poor capacity-building

Respondents noted concerns about the strategic decisions on location, governance structure, and capacity development, which was the case more often with national-level health stakeholders. According to one health policy-planner:

[The] focal point of health sector decentralisation [is] not identified, for example, whether the National Planning Commission (a national apex body) or the Ministry of Health. There was also limited provision of capacity development at national and local levels. Also [there was] not clearly defined governance and political structure, and their role in the public sector [was not defined]. (56-year-old male, national stakeholder)

On the same topic, a health worker respondent stated:

Some policies exist only in papers, but [there are] not clearly defined roles of local health authorities. As a result there is always conflict [concerning] who does what, who has what, and who gains and loses as a result. There are always poor/inadequate provisions of healthcare monitoring and auditing in place. Similarly, there is a lack of local-level health and wellbeing plans. (39-year-old female, HSP)

A similar concern was raised by one service user:

There were poor financial mechanisms, mainly fund flow systems from the central government to local level to local health facilities. As a result, several needs-based health plans were not implemented, nor did they reflect poor people’s needs and interests in the programme planning and management cycle. (32-year-old female, HSU)

HSUs and HSPs alike noted concerns related to capacity-building brought about as a result of decentralisation.

Lack of supplies and infrastructure

Challenges related to supplies was a stated theme. Some healthcare providers described that in healthcare services there were insufficient medicines throughout the year, so people cannot provide better services to poor people.

Because poor people cannot afford to purchase some medicines from [the] health centre as they don’t have any budgets at the local level, they cannot provide every service, so we failed to address the needs of poor people. (41-year-old male, HSP; 38-year-old female, HSP)

They further highlighted that though they have decided in the management committee to open up 24-h ‘obs and gynae delivery’ services, because of the lack of infrastructure and financial support, they could not manage this. The chair of the health service management committee described his struggles with health infrastructure: ‘We didn’t [even] have any extra room for the patients’. Fear of lack of regular supplies, mainly essential medicines, was a recurrent explanation for poor-quality services (51-year-old male, district stakeholder).

Supervision and participation

Concerns about the supervision of, monitoring of and participation in local health services were also noted. One respondent described that:

There is a poor supervision and support mechanism between the district [District health office] and primary healthcare centre; therefore, it is difficult for me being an in-charge centre to assure the community that they will get what they demand. In fact I often felt reluctant to talk [to] the local people about their health needs. (37-year-old female, HSP)

Participation, on the whole, appeared relatively nominal. While some people were involved in the planning and management levels, the people who were poor and marginalised were often left out. A medical doctor, for example, lamented:

I would like to [be] involved [by] shar[ing] my voice in the health centre as I [am] never ever invited for the general meeting. (48-year-old male, HSP)

Similarly, an elderly patient shared:

I am a member of Kisan Samuha (farmers’ group). I am a member of Adibasi (indigenous) women’s group, and promoting vegetables and nursery gardens [is] the major [job] of the group. I would like to engage myself in the community health works. I am also a member of one women’s group and my sister-in-law is a community health volunteer, for tuberculosis. I want to work with these health workers, especially in the sector of water, health and sanitation, and environmental health. No, I don’t know how to join in as I was never invited to become a community health member. (43-year-old male, HSU)

Discussion

In this study, I found that the idea and practice of decentralisation indicates that the body of locally elected officials who represent the local government or local political unit would be a viable institution to which power and authority can be devolved. This notion holds some important implications, based on the findings of the study that local political authorities are close to local communities and can therefore best represent their interests. Local community involvement ultimately increases the effectiveness, efficiency and responsiveness of interventions (see Cheema and Rondinelli, Reference Cheek, Lipschitz, Abrams, Vago and Nakamura1983; Regmi et al., Reference Regmi2010).

Similar to previous studies (see Bossert, Reference Bossert2000; Bossert and Beauvais, Reference Bossert and Beauvais2002; Bossert et al., Reference Bossert, Chitah and Bowser2003; Collins and Omar, Reference Collins and Omar2003; Omar et al., Reference Omar2007; Sreeramareddy and Sathyanaraya, Reference Sreeramareddy and Sathyanaraya2013; Mohammed et al., Reference Mohammed, North and Ashton2015), the findings of this study have supported the claims that decentralisation of PHC services through devolved power and authority are seen as beneficial. In particular, local health facilities are gaining some degree of freedom from the central government. Local officials are being held accountable to people’s needs and interests, recognising consumers’ voices and choices by health systems, and engaging in participatory service planning and management, as well as health service performance. Additionally, poor and excluded members of the community have clearly recognised the benefits of decentralisation. Similarly, sharing the study findings to the community involving the local HSPs, civil societies and policy-planners, and decision-makers would allow an opportunity to hear what the community have to say, and this dialogue would give HSPs at both ends of the spectrum an opportunity to evaluate their own thinking in service delivery.

Notwithstanding the above, this study has also indicated that decentralisation may generate a series of micro-level problems in achieving the objectives of devolution. Omar et al. (Reference Omar2007) supported this view by recognising that decentralisation policy in Nepal is coupled with a faulty transfer system and differing levels of efficiency and capacity, which might also hamper the pursuit of regional and local equity in health service delivery and management, as linking the devolution of authority and power to locally elected government authorities is not a sufficient condition to ensure the participation of civil societies and groups in decision-making processes.

Decentralisation at its best has not been fully reflected in practice in Nepal. This study noted that political representatives were still at the centre of health services plans, and they often reflected their parties’ vested interests rather than people’s needs and aspirations. In addition, this study highlighted that central government is still in control of all financial aspects, including staff hiring and firing. Roles and responsibilities have not been clearly demarcated between central and local government; and external development partners’ (donors’) roles have not been made clear in terms of developing and implementing local health programmes and policies. These tendencies run against the grain of decentralisation. Furthermore, some service users felt that there were inadequate reflections of poor people’s healthcare needs and interests in programme planning and management due to discrimination by practitioners.

Nepal is still in a transitional phase due to political turmoil and instability. As a result, the local government is not operating within the principles of local governance systems. Nevertheless, recently the Government of Nepal has successfully promulgated the new constitution of 2015. In accordance with law, article 35 has fundamentally recognised that ‘each person shall have equal access to healthcare’, especially targeting the dalit communities (ie, poor and marginalised people) (Government of Nepal, 2015).

Strengths and limitations

This study has not only explored some insights into the benefits and disadvantages of decentralisation from the wider stakeholders’ perspectives in this particular country, but also offers lessons learned to provide researchers or policy-makers fodder for further research in the devolution of the healthcare sector. Imbued in this study were three limitations: first, the central purpose of decentralisation was to increase the coverage, efficiency, equity, effectiveness and quality of health services, thereby improving the health status of the population (Bossert, Reference Bossert1996). However, this study focussed on exploring and examining the effects of decentralisation on provision of PHC services and health service performance from the viewpoints of HSUs and HSPs only.

Second, this study adopted a qualitative-driven mixed method design (QUAL→qual), where the qualitative core component was the FGDs, which in theory used ‘inductive theoretical drive’ with the sequential qualitative supplementary component (SSIs and Os). In theory, a mixed method design would strengthen the research study, but in practice it is not always easy to do (Morse and Niehaus, Reference Morse and Niehaus2009).

Finally, this study employed the purposive method for sampling. Although the researcher captured a diversity of participants in terms of ethnic source, age, sex, location, services category and role in the community, the sample precluded the identification of those who had no access to or utilisation of the health services.

Conclusion

In spite of the methodological limitations, the results from this study do make a valuable contribution to our knowledge in terms of understanding and examining healthcare through qualitative-driven mixed methods design using a QUAL→qual approach. Qualitative methods are often criticised as a ‘second-class science’ (Morse, Reference Morse2006: 315) because findings are related to a specific context; therefore, knowledge obtained from this approach would be difficult to transfer to another context. This study has, however, recognised the effectiveness of qualitative designs in terms of enacting an in-depth understanding of a problem (decentralisation in a third-world country) and exploring possible options within that given context. The findings from the study would be an invaluable source of information that would directly benefit the marginalised community that it seeks to assist.

For these reasons, I believe that the approach has merit for pursuing additional research (i) to examine and understand the impact of decentralisation on output and outcome objectives – improving equity (access and coverage), efficiency, quality and improving health outcomes, and (ii) to translate its implications across a wider scale involving more PHC services to improve the quality of services, considering the marginalised or excluded groups (women, children, poor religious, cultural and ethnic groups) is now the priority (see Bossert, Reference Bossert1996).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks all participants who participated in this study.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of relevant national and institutional guidelines and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study was approved by the NHRC and UWE ethics committees.