A. Context: The “Advance” Purchase of Vaccines and the AstraZeneca Litigation

The Covid 19-pandemic has had a revealing effect on numerous legal relationships. Central themes have been “rights” issues, the extent of the regulatory power of the State, and the precarious balance between risks of life and compensation schemes for keeping things going. Turning to contract law, we observe a multitude of adjustment needs caused by the changes and interruptions of all production cycles, including education and culture. My focus here is on structural problems of the contracts concerning the “fight against the virus,” the EU vaccine purchase contracts. In this context we find contract clauses that have received a recent prominence and wide use in the world of international business contracting, “best efforts” clauses. They are employed for “softening” obligations. Their functions and problems, and their place in a “taxonomy of obligations,” will be developed in this Article from the perspective of a draftsperson.

Contracts are individualizing legal relationships. No important contract can be understood without its “personal” narrative and its context. Consequently, I will first shortly turn to the narrative and context of the EU vaccine deals, a multi-billion-dollar game of highest social and political priority.

The news about the first outbreaks and the deadly potential of the infectious disease in late December 2019 prompted immediate research on and development of curing and immunization strategies. In my hometown of Marburg in Germany, a traditional center for virus research and vaccine production, I witnessed as early as February 2020 the rapid start of related academic projects, including immediate public research subsidies, for addressing the development of an effective viral vector vaccine that is presently in the last trial phase.Footnote 1 Concurrently, 100 kilometers to the southwest, in Mainz, a small high tech drug developer, BioNTech rushed to modifying an ongoing cancer vaccine project on an innovative “mRNA” technology. Driven and assisted by the global outreach of US pharma giant Pfizer, this led to a highly successful Covid 19 vaccination formula in the unprecedented time of less than a year. Similar projects were conducted around the globe. In the US in early 2020, the Trump administration started “Operation Warp Speed.” It included the provision of subsidies that finally amounted to an authorization of US $20 billion for research, development, the building of new production facilities, and prioritized national procurement of vaccines.Footnote 2 Within the European Union, subsidies were initially offered by some individual Member States. A report of the German government in a “Small Inquiry” procedure of the Bundestag of February 1, 2021, lists authorized subsidies, totaling 740 million Euro to three firms operating in the Federal Republic.Footnote 3

To avoid an unequal treatment within the EU, the Member States decided for a common purchase and distribution of the vaccines. They authorized the EU Commission as a common agent for negotiating and concluding the relevant agreements with the most promising production firms. The mentioned report to Members of the Bundestag lists six firms with which the Commission, represented by the Commissioner for Health and Safety, signed so-called “advance purchase agreements” or “buying options” between the end of August 2020 and January 2021.Footnote 4

All agreements were classified “confidential.” In view of a protracted start of the vaccination programs and an alarming scarcity of vaccine deliveries, the public, and finally the European Parliament, required the disclosure of the relevant contract documentation. Thereafter, the sizable agreements were made public. All documents that are now available by special request, contain partially blacked-out “sensitive” clauses. The “editing” has been done—as far as can be seen—largely by discretion of the firms, with uneven results concerning the intensity.Footnote 5 For purposes of analysis, I will use the six published contracts,Footnote 6 but I will mainly refer to the most readable sets, those between the EU and AstraZeneca, the existing “Oxford” vector vaccine, and CureVac, the “Tübingen” mRNA vaccine, that is still under review for approval, as of June 2021.

The AstraZeneca contract is of special interest because the EU Commission blames the firm for breach of contract. From their legal point of view, the firm has failed to deliver the specified number of vaccine doses. The firm contends that it did not violate the agreement because the delivery targets mentioned in the schedule are limited by a best efforts clause. Both parties did not reach a settlement in the conciliation period of 20 days, stated in the agreement.Footnote 7 After this period, the Commission filed a lawsuit before the court appointed in the contract, the Tribunal de première instance francophone de Bruxelles, Section Civile, Belgian law being applicable. They asked for the delivery of 300 million doses and for the assessment of penal damages (“astreinte”) corresponding to this amount. According to a press release they also cancelled the contract.Footnote 8

On June 18, 2021, the single judge handed down a preliminary decision with a Solomonic result.Footnote 9 The 67-page decision reports the complete negotiating history with all relevant clauses translated into French. The judge is particularly concerned with a priority delivery clause of 100 million doses in a contract between the University of Oxford and the UK subsidiary AstraZeneca UK Ltd. dated May 17, 2020.Footnote 10 In an agreement on August 24 and 28, 2020, this subsidiary signed a respective priority agreement with the UK Government.Footnote 11 As noted in the reference to the contract text,Footnote 12 the EU signed their agreement with the mother company, AstraZeneca AB, Sweden, on August 27, containing Article 13, stipulating that the firm:

(e) … is not under any obligation, contractual or otherwise, to any Person or third party in respect of the Initial Europe Doses or that conflicts with or is inconsistent in any material respect with the terms of this Agreement or that would impede the complete fulfilment of its obligations under this Agreement.

In the judgment which would need a special extensive treatment, the judge “pierces the corporate veil” by looking at AstraZeneca as one unit. She partly discards the priority agreement by putting all delivered doses together. But she clearly underlines that all deliveries are “best efforts” deliveries.Footnote 13 Applying the French/Belgian doctrine of an “obligation de moyens,” that will be explained below,Footnote 14 she reaches the conclusion that currently AstraZeneca is only obliged to deliver, at specified dates in July, August, and September 2021, a total of 50 million doses, instead of the 300 million doses requested. But she also assesses penal damages for the case of non-delivery. Commenting on the judgment, AstraZeneca already quipped that they would follow the judgment with pleasure.Footnote 15 The President of the EU, Ursula von der Leyen also welcomed the decision, stating: “It … demonstrates, that it [the vaccination campaign] was founded on a sound legal basis.”Footnote 16

In the following, I will leave the “interpretive” view of a court concerned with contract litigation. I will rather concentrate on the relevant clauses from a drafting perspective. At first sight, a cautious approach of the firms, by promising their “best efforts,” seems more than warranted in our situation. At the time of negotiating the deals, the products to be delivered were, at most, in a trial stage.

But contracts are concerned with future events. And events in the future can be made present by using conditions. If the developers will be ultimately successful in their efforts, there will be a point in time when the developed and admitted vaccines will become marketable goods. No doubt, the production, supply, and delivery will be complex. How is this process reflected in the contracts? What are the projected contract risks, the relevant contract clauses, their treatment of performance issues, and the underlying theoretical aspects?

B. The Use of “Best Efforts” Clauses in Two Vaccine Contracts

Despite the complexities associated with the development of Covid 19, vaccines the drafting of a purchase contract is not rocket science, even if billions of Euros are concerned. States and private health organizations routinely procure newly developed vaccines. We have been witnessing the annual need for fighting influenza with adapted new vaccines and the outbreak of no less than three pandemics since the turn of the century, not accounting for the local or regional events with Covid, ZIKA, and the MERS outbreaks. In an earlier short paper on the structural defects of the vaccine contracts, I tried to show that a drafting exercise would have to contemplate at least three different factual stages for designing an appropriate contractual coverage:Footnote 17

Stage 1. The initial research process, whether done by academic institutions or pioneering research firms, is open end. The target is clear, but an honest assessment of possible failures of the project is part of the exercise. The necessary incentive schemes and related agreements with subsidizing institutions are technically service contracts combined with reporting and monitoring the progress of the investigation.

Stage 2. The development project is still open end when a viable drug enters the costly testing phases. Even if it passes all tests, including the admission process by the various public agencies, the largescale industrial production of the drug may prove technically or economically difficult or even inviable. The building and/or adaptation of laboratories for the various product components imposes additional risks of delay or failure.

Stage 3. Once the testing and admission stages are passed, and the marketability of the vaccine is being established, the manufacture, sales and delivery stage requires legal detail.

Let us look how these stages are technically covered in the contracts, using the examples of CureVac and AstraZeneca.

I. CureVac

Negotiating with a public counterpart requiring a new vaccine the developers will likely propose different commitments in the individual stages. In Stages 1 and 2 they will commit themselves “to do what they can” in view of the target; in legal terms, they will offer their “best efforts.” This seems to be expressed in Article 1.3. subsection 2 of the CureVac Contract:

On the basis of this APA [advance purchase agreement], the contractor commits to use reasonable best efforts (i) to obtain EU marketing authorization for the Product and (ii) to establish sufficient manufacturing capacities to enable the manufacturing and supply of the contractually agreed volumes of the product to the participating Member States in accordance with the estimated delivery schedule set out below in Article 1.11., once at least a conditional EU marketing authorisation has been granted.Footnote 18

Note that the clause does not just talk about using “best efforts” but limits the required, hopefully energetic, action by adding the term “reasonable.” This is a conventional practice for making clear that “best” does not mean “utmost.”Footnote 19

Looking closer at the Definitions under 1.2 of the contract, we find, however, that the “best efforts” commitment, fitting for Stages 1 and 2, is carried over to the technical regulation of Stage 3, the manufacture, sales, and delivery process. It reads:

Reasonable best efforts: a reasonable degree of best effort to accomplish a given task, acknowledging that such things as, without limitation, the complex and highly regulated nature of the Product; the timely availability of raw materials, inventories and liquid funds; yield of process; the success of necessary clinical trials programs to support safety and immunogenicity data for the Product; the approval of the final Product formulation; contractor‘s commitments to other purchasers of the Product; other reasons relating to uncertainties of producing a new vaccine for a new disease with an mRNA platform for which vaccines have not yet been registered by regulatory authorities; and any other currently unknown factors which may delay or render impossible, contractor‘s successful completion of the particular task, including, without limitations… are beyond the complete control of the contractor….Footnote 20

Within this definition, the wording hides two important and surprising impediments for a priority delivery of the requested vaccines that are under sole control of the delivering party: “lack of funds,” and particularly, “commitments to other purchasers of the product.Footnote 21”

It is questionable why the EU Commission accepted these extensions of the “reasonableness” concept within this kind of best efforts clause, at least, if they wanted to be purchasers of first resort. The silver lining might be that a Continental civil court could be tempted to rate this a “surprising clause” in its context and strike it as being void. However, in a commercial arbitration setting, including the applicable law of one of the typical common law contract jurisdictions, the clause would likely prevail. Here, courts would definitely start from the assumption that an actor like the EU Commission should understand what they have signed.

Before we turn to the theoretical background of this explicit unilateral use of a best efforts clause by a delivering party, we will look at the treatment in the AstraZeneca Contract.

II. AstraZeneca

The AstraZeneca Contract uses the “best efforts” idea in a different way, possibly inspired by the common law origin of the contract form introduced by the company lawyers. Article 1.9 in the definitions section contains a detailed description of the two contracting parties.Footnote 22 They are styled as actors who are both supposed to be acting with “Best Reasonable Efforts.” This “bilateral” use is found in US and English cases, discussing contracts with best efforts clauses. The analysis of the courts interpreting the variants of the clause in individual contracting contexts suggests in the eyes of US commentators that “best efforts” may be understood as a matter of attitude,Footnote 23 a degree of honesty and fairness, in individual cases even excelling the implied “good faith” standard in normal business agreements.Footnote 24 Explained in this way, it would not relax the obligation for production and delivery, as in the “unilateral use” shown in CureVac. To the contrary, it would raise the standard of care of both parties.

Article 1.9. reads:

Best Reasonable Efforts means

a) in the case of AstraZeneca, the activities and degree of effort that a company of similar size with a similar-sized infrastructure and similar resources as AstraZeneca would undertake or use in the development and manufacture of a Vaccine at the relevant stage of development or commercialization having regard to the urgent need for a Vaccine to end a global pandemic which is resulting in serious public health issues, restrictions on personal freedoms and economic impact, across the world but taking into account efficacy and safety; and

b) in the case of the Commission and the Participating Member States, the activities and degree of effort that governments would undertake or use in supporting their contractor in the development of the Vaccine having regard to the urgent need for a Vaccine to end a global pandemic which is resulting in serious public health issues, restrictions on personal freedoms and economic impact, across the world.Footnote 25

A minor point in this definition is an obvious misunderstanding or sloppiness of the draftspersons. They reversed the normal order of the adjectives “best” and “reasonable” attached to the noun “effort.”Footnote 26 It is an example of a classical type of drafting mistakes that will eventually enter lengthy contract forms. They will typically start as editing errors and will be carried on until detected in a new negotiation. For hiding their mistake, hard-nosed draftspersons might even allege in this situation that we are dealing with a new, particularly smart formula. The conventional technical order of both terms follows a typical rule/exception scheme. In a usual best efforts clause the obliged party will be required to use their best — not average, or less — efforts for achieving a specified goal, limited by adverse, hopefully specified, circumstances that would reasonably lead to a release from the primary obligation. Not every single stone in the last corner is to be turned over twice. The clause in the CureVac Contract, cited above, demonstrates the correct order despite its dubious extension to matters that are usually not included in the specification of the reasonableness limitations.

The serious and problematic point, that is one of the two central ones in the AstraZeneca litigation, is the operation of the defined best efforts formula in the contract itself. One would assume that it would, for example, be used in a possible clause concerning the drug admission process, as in the CureVac Contract. That clause does not exist in the AstraZeneca Contract.Footnote 27 Indeed, part b) of the definition, applying to the Commission, is not used at all in the whole agreement. It could, of course, prevail as a “good will” statement. All key obligations in the contract are formulated in a straightforward manner, especially “shall pay,” and “shall provide” in the funding and payment context in Article 7.Footnote 28 The only prominent use of the best effortsclause is found in Article 5 “Manufacturing and Supply”:

5.1. Initial European Doses. AstraZeneca shall use its Best Reasonable Efforts to manufacture the Initial European Doses within the EU for distribution, and to deliver to the Distribution Hubs, following EU marketing authorization …Footnote 29

In Article 5.4., the formula is used for the choice of production sites preferably in the EU, which includes for purposes of the agreement the UK. Thus, in the AstraZeneca Contract, the “unilateral” use of a best effortsclause comes, literally speaking, “through the back door.Footnote 30” This “exclusive” use of the formula within this particular context of the contract is the basis for the excuses of AstraZeneca for non-delivery. They contend that their delivery obligations, also taking account of the comparatively low price per dose, are limited to a mere effort instead of being governed by the “normal” obligational level of performance in a procurement setting, namely the production and delivery of the described items in good faith limited by force majeure.Footnote 31 The Brussels Tribunal, in principle, accepts this point.

As mentioned above, under a superficial “American” reading of “best efforts” as a qualified bilateral good faith clause, setting a “standard” for both parties, this line of argument would hardly prevail. But the applicable law, including the rules of interpretation of this contract, common law by nature, is Belgian law. And the used clause is unspecific. It does not give any further hint how the provided production and delivery process should be calibrated in detail, applying a best efforts wording. At least in the definition section, it rather sounds like a general goodwill clause. But as I mentioned when shortly reporting the decision of the AstraZeneca case, a Belgian judge who is used to thinking in terms of “obligation de moyens” will read “best efforts” in the way it is technically understood in the context of the decisions and doctrine relating to the Code civil.Footnote 32

In the AstraZeneca litigation, an additional point has not been raised. The representatives of the firm obviously realized that, in private commercial contracting context, it would be a weak argument that “the others (e.g., CureVac or Pfizer/BioNTech) got a better/softer deal,” particularly advanced by a party who proposed the contract scheme and the initial draft.Footnote 33 For this party, the important “level playing field” principle of public procurementFootnote 34 may be of little avail.

C. “Best Efforts” as a Mode of Performance – the Obligation and Performance Riddle

Is the concept of “best efforts” a standard, or rather a mode of performance? The easiest way of settling this divergence in the functions of the clause might be the verification that it is both. We might be confronted with specific traits of the different legal orders, and we would have to live with the differences. The iconic comparative law text of Zweigert & Kötz seems to point in this direction. In the context of “claims to performance,” the authors discuss the different approaches.Footnote 35 They start with German law dealing with the theoretical priority of a claim for specific performance, which is “not of much use.”Footnote 36 For qualified personal services, they point to a rule of civil procedure—Section 888 of the statute on civil procedure—that limits enforcement.Footnote 37 Here, obviously the “character of the obligation” matters. For French and Belgian law, a seemingly related problem is being discussed in the section on breach of contract and the claim for damages, particularly concerning the issue whether a seller who fails to deliver may excuse himself or herself by claiming that he or she was not at fault. The old rule of the French Code civil, Article 1147 —until 2017—would deny this. Only force majeure or cas fortuit would be a reason for excuse. But in certain situations, fault is a viable excuse. Tony Weir’s English translation of Zweigert & Kötz nicely restates the original French doctrine:

However, the Code civil also suggests that the debtor’s obligation as regards performance is only to show tous les soins d’un bon père de famille (art. 1137). For many years now the courts have found a way of resolving this apparent conflict: they apply the stricter rule of art. 1147 in cases where it emerges from the contract that the debtor has promised to procure a certain result – this is an obligation de résultat – but it appears what was agreed or from the thrust of the contract that the debtor was not promising a given result but only to use his best efforts in that regard, this is simply an obligation de moyens, and there is liability for non-performance only if the creditor can prove that the debtor did not try as hard as a reasonable man would have done in the same circumstances.Footnote 38

It is not by accident that Tony Weir, a most distinguished English comparative lawyer known for the subtlety of his translations, uses the term “best efforts” obligation, for giving a proper meaning to the idea of an “obligation de moyens” in this context.

Obviously, the French doctrine since the analysis of René Demogue,Footnote 39 followed also by Belgian law,Footnote 40 looks at the contracts from an objective point of view. As a matter of fact, the treatment of doctors and the efforts provided by the service of lawyers are typically treated as these supposedly softer “obligations de moyens.”Footnote 41 This is the judicial perspective. The crucial question comes up under a drafting perspective. Can—if one uses the French distinctionFootnote 42—a “statutory” obligation “de résultat” be converted into an obligation “de moyens” in the contract between the parties?

The answer is “yes, within limits,”Footnote 43 not only confined to French or Belgian law,Footnote 44 but in all major transaction orders on the globe that accept the premise of a general freedom of contract. The standard sales example is simple enough. Of course, it would be classed as an “obligation de résultat” under French law. However, in a commercial context, I could reasonably contract for a delivery of last resort, probably of an uncertain quantity and/or an uncertain time, with unspecified quality changes, likely at a lower price. It may be in the interest of both parties to share upstream risks in the production, storing, and shipping phases. Moreover, I could deal with an even softer scheme “to be considered” in a seller market. Clearing sales in food or fruit markets are daily illustrations in which quality and quantity risks are shifted to the customer, and even these deals, if happening regularly, may be covered by umbrella agreement with the purchasers. The commitment “I’ll try to get that widget for you” is standard under many circumstances and mostly meant as a binding commitment, weak as it may be. At the other end of the scale are fixed, guaranteed, and dedicated deliveries or services “just-in-time,” with iron clad penalties/liquidated damages clauses for non-performance.

The underlying theoretical question that has already been implicitly raised by the examples just given is whether the world of drafted obligations follows a clear-cut division between “result obligations” and “best efforts obligations.” Here, the answer is no. But the drafting practitioners should be happy that the French doctrine, circling around the alignment of the seemingly contradicting old Articles 1137 and 1147 of the venerable Civil code of 1804, has been producing a simple and plausible clear cut “modular” structureFootnote 45 to their efforts of entertaining a practical distinction for aligning the interests of the parties for “softer” forms of bindingness in individual cases. In that sense, the original French concept, which has been implicitly around in all legal orders in some way, is a good starting point for detailing the individual obligations in the negotiating process.Footnote 46

As in many other cases of the institutional development of private law, the result/effort distinction is rooted in the changes of contract law in the 18th and 19th centuries. In this period, in both the “romanistic” and the “common law” legal orders, a limited, action-based “law of contracts remedies” has been transformed into a free-wheeling substantive law of contract, of course leaving some traces of the former approach.Footnote 47 An example is the mentioned contradiction of articles 1137 and 1147 Code civil.

The debates about the transformation of the original Roman contract actions into a “modern” substantive law of obligations in the middle of the 19th century are telling. The most erudite legal scholar of his time, Friedrich Carl von Savigny, takes pains to specify and clarify the point. This has been largely forgotten in the remainder of his century. In his final work, the unfinished two volume treatise on the Law of Obligations as a Part of the Present Roman Law, Savigny stresses that there is a pervasive complexity of obligations that should not be put in the straitjacket of the simple divisions of the former Roman law actions.Footnote 48 The Roman sources are, indeed, ambiguous at this point. The important Roman jurist Gaius, looking at the actions in personam, Footnote 49 suggests dividing the obligations between “dare”—a “giving,” technically a “handing out,” probably lurking around in the French “résultat;” “facere”—a “doing, acting,” later including “omissions,” vaguely related to the French “moyens;” and a fairly dubious “praestare,” possibly derived from the formulae in tort actions.Footnote 50 Savigny insists that the admissible variety of obligations, to be shaped by the will of the parties, forbids a neat subdivision of this kind.Footnote 51 He stresses that the terms used by Gaius are rather “flexible.”Footnote 52 Indeed, in a footnote, he can show that in one reported case, the “facere” obligation is not less stringent than the “dare” obligation but even embraces the “dare.”Footnote 53

The technically least sophisticated contract system, that of the various common law jurisdictions, has had the easiest time for adaptation to the openness of negotiated obligations. It never faced the constraints of codification and the related doctrinal fights in the brave new world of freedom of contract. It is questionable, however, whether Farnsworth’s analysisFootnote 54 for the jurisdictions in the US, to understand “best efforts” as an overarching “bilateral standard,” is correct in general. Here, as in many other cases, we should not entertain the comparative law cuckoo that, despite similar results in practice, the different spirits of the common and continental laws emanating from the different legendary deep forests of Nottingham, or those of the Druids in the middle of France, require a fundamentally distinct conception of legal problems.

“Best efforts” may become a “bilateral standard” if both parties are interested in an individual obligational commitment of the same kind, namely, not to perform in a straightforward manner but to do their best that the specified individual targets in the contract are being met. In other words, “best efforts” is a matter of the individually specified obligation and its performance. The more frequent generic cases for best efforts that are mentioned in the French hornbooks, like the doctor-patient relationship, concern cases in which one party makes a serious, well understood effort, and the other is willing to react straightforwardly by paying the contract bill.Footnote 55 However, in the sphere of negotiated commercial contracts, there are many nuances of obligation. A simple division between “strict” and “best efforts” obligations would hardly be adequate for understanding these arrangements. Here, the resolution of disputes about the commitments of the parties is a matter of looking at the contractual text in its context and of abstaining from simple black and white classifications.

D. A Primer on the Taxonomy of Obligation

In the negotiation and drafting of commercial contracts, “bindingness” is a central aspect.Footnote 56 Parties try to hedge their commitments to the very last minute of signing. If costly commitments beyond the normal outlays are concerned, we witness a sort of “Coasean bargaining in contrahendo”Footnote 57 concerning the coverage of costs, neatly separated from the issue of whether a final agreement has been reached. Substantial agreements contain clauses specifying when and under which conditions the agreement will become binding.Footnote 58 In the course of negotiating a deal, the parties will try to fix individual chapters and leave others open, adding a note at the margin “to be discussed,” abbreviated typically with “TBD.” This indicates that the finished chapters contain a sort of “social” bindingness. Although it is clear to the parties that the text is not binding legally, reneging comes, at least, at a reputational cost. At this point, a lack of cooperative behavior will be sanctioned by blaming and shaming. “You might not wish to make a deal with this counterpart,” sometimes leading to strategies of the other parties to add a matching risk component in their first offer. Tougher reactions may be the factual exclusion from new business, or even exclusion from “clubs” like business meetings, commercial platforms, or information circles. Numerous important documented business arrangements,Footnote 59 in some cases named “letter of intent,” never reach a legally binding stage despite being honored meticulously by the parties.

The world of binding commercial contracts starts with arrangements in which parties are hedging their commitments with “softener” clauses, especially using the term “best efforts,” mostly mitigated by explanations of what they consider as reasonable under the circumstances. A good example is the CureVac Contract, treated above, including the potentially tricky effort to include commitments to third parties, as an excuse for non-performance.

Although “best efforts” may be used for a varying intensity of obligation, the arrangements of this kind may be grouped under this catchword. As mentioned before, there are instances of generic best effort-contracts, although in the canonical French examples the requisite “efforts” of lawyers and doctors could also be framed by detailing their obligations, namely their professional duties under the given circumstances. In a litigation about professional malpractice, the statement “But I exercised my best efforts” alone would hardly excuse the defendant.Footnote 60 This indicates that “best efforts” is mostly used if the parties are not prepared to detail their duties, particularly if the expected benefits from specification are lower than the drafting costs, including the frustrations of commercial parties when lawyers elaborate on the obvious.Footnote 61

The “stronger” commitments may be classed under a rubric of “performance contracts” and “guarantee contracts,” with two immediate caveats. First, all three groupings of legally binding agreements are on a sliding scale; they are not new ”contract types,” as treated in the Continental contract law codifications. Second, the term “performance contacts” should not be understood as a verbal collocation of the obvious. All contracts are technically concerned with a future, named performance. Here, the term “performance” is used for distinguishing them from the arrangements in which parties try to hedge their obligations by reference to their serious efforts to perform.

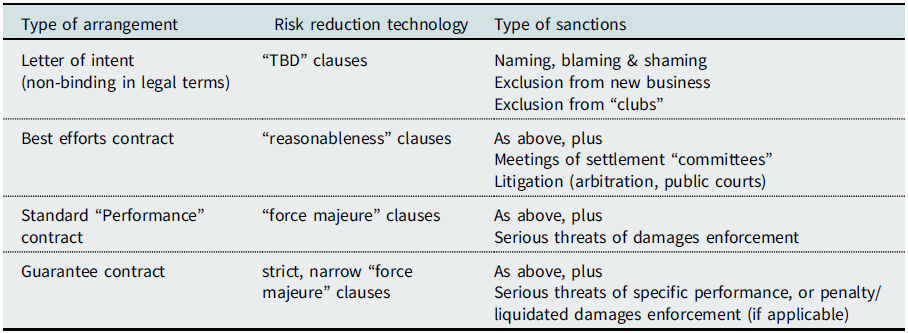

In all groups of arrangement, the characteristic “risk reduction technology” differs. In best efforts contracts we find typically a “reasonableness” limit that is at the forefront of constraining the obligation to use the best efforts to perform. In “performance contracts,” this role is assumed by force majeure clauses. These do also show up in best efforts contracts, but they do not technically matter there, because the incidence of normal “force majeure” events would make the best efforts performance “unreasonable” anyhow. If I use “strict force majeure” as the “risk reduction technology” for the strictest of all arrangements, the guarantee contracts, I am commenting on instances in the drafting and negotiating exercise in which “force majeure” is extended to, for example, labor disputes or administrative consent, events that are not completely out of the control of the debtor.Footnote 62 This leads to the following scheme of a tentative taxonomy of bindingness and enforcement of commercial arrangements (Table 1):

E. Searching for a Fitting Contract Scheme

Whereas the classical codification movement of the last two centuries has been a high-flying effort of capturing emanations of a “jurisprudentia perennis,” the prosaic exercise of drafting commercial agreements follows the needs and variety of the day. Reading large contracts for some decades, I could witness all sorts of “contract fashions.” A prominent example for the 60’s to the 80’s has been the “joint venture” movement in all possible and impossible situations. The financial sector supplied the idea of covenants, which rapidly spread out to other fields with a limited adaptation potential. This also happened with MAC-clauses, including their entropic growth in size in the contract documentation. “Best efforts” clauses have been around for a long time because they were fitting to certain types of arrangement in which—demonstrated by the examples of the French doctrine—an obligation could not be framed simply in result terms. But they are currently en vogue in the industry, with dubious consequences.

Discussing the vaccine development above, I pointed to the initial Stages 1 and 2 concerning the open-end research and the uncertain development of a functioning drug, including the complexity of testing and organizing a new production and distribution scheme. These stages are captured adequately by the concept of “best efforts” from a drafting perspective. There are many commitments in practice in which experienced draftspersons will be happy to start working with the best efforts-idea, detailing it in the contract text. But it is both fashion and/or strategy using the best efforts-approach in a clear-cut production and delivery context. That is not to say that using the idea is illegal. But it may not work.

At first blush, it may sound smart to keep the arrangement as open as possible. And the “office memo” to the principals may state: “We have succeeded in negotiating a deal that keeps all options open for the firm.” Scott and Triantis, in their analysis of best efforts clauses, point to the downside of this strategy.Footnote 63 The “cheap” openness ex ante may become costly ex post. It is trivial that, fortunately, only very few commercial transactions dealing with definable performances, using best efforts clauses for hedging the commitment, go to court. However, as Scott and Triantis explain, in this unlikely situation, the court will have to deal with a “vague term” and be required to “complete the contract.Footnote 64”

It should have been easy to formulate in the vaccine contracts that, after reaching the point of admission of the vaccine and the demonstration of the viability of a large-scale production, the parties would enter into a standard production and delivery relation, a “performance contract” in the meaning developed above, including a highly detailed force majeure clause expressing all potential constraints in the production and delivery as excuses. Whenever an “openness” of a “contract future” is at stake, conflict avoidance demands to think twice about the selection of the starting point for a fitting draft.

F. An Afterthought

The EU vaccine contracts are a story of failed ambitions and misleading contract choice. The lawyers of AstraZeneca may be disappointed because they introduced a common law style “industry contract” which might work between commercial parties, or vis-a-vis the UK National Health Service, if it would have stayed in a common law setting, including, preferably, commercial arbitration. They accepted a reading of this contract under Belgian law by a Belgian civil court that will be influenced by the seemingly fundamental distinction between “obligations de résultat” and “obligations de moyens.” They were fortunate finding a judge who expressed an understanding for the freedom of the parties to hedge their risks in these terms. If the judge would have taken the objective route for the present arrangement, she might have arrived at a textbook classification:the delivery of vaccines concerns a “résultat.” They took an unnecessary risk and got away with a fuzzy contract that could have been re-written by a court.

Turning to CureVac, it is likely that the introduction of an escape clause in the surprising context of the definition of “reasonableness” will not matter in practice. The query of third party commitments will probably be irrelevant in view of a generous supply of other mRNA vaccines in the second half of 2021. Why they styled a future delivery contract as a best efforts arrangement will remain their secret.

The critique of the drafting efforts of AstraZeneca and CureVac does not exonerate the other producers and their contract management. To the contrary, their extensive blackening of clauses does not show strength. A closer analysis would probably also show a similar fuzziness in these “copy & paste” contracts.

The visible flaws and associated queries of the vaccine contracts contain a general message for the international drafting profession. Best efforts clauses are no panacea for negotiating and drafting efficient major business deals. A stronger effort for specification of performances makes good sense under many circumstances. Best efforts clauses will work for the parties if they fit the transaction.

Table 1. Taxonomy of Bindingness and Enforcement

Note, that these four stages of bindingness in contracting are on a sliding scale. They are NOT “new” contract types.