The Italian political system at the dawn of transformation

The Italian political system on the eve of the twentieth century had arisen from a partly customary evolution of the Statuto Albertino, which had been established in a very special period: namely, the European revolutions of 1848.

While, in its written version, the statute envisaged a constitutional monarchy in which executive power was in the full orbit of the crown, an aspect of the governments led by Cavour, the government established a relationship of trust with parliament, particularly with the Chamber of Deputies. The Senate, in fact, not being elected but selected by royal appointment, tended by custom to confirm the decisions taken by the lower chamber, although in a context where the two majorities tended to coincide. Those entitled to vote were about 2 per cent of the population of the kingdom of Sardinia,Footnote 1 a percentage that remained virtually unchanged until 1882, when parliament approved the first great suffrage enlargement.Footnote 2

In essence, there was an evolution from a system of constitutional monarchy to ‘almost’ a parliamentary monarchy, where that ‘almost’ marks a substantial difference from an entirely parliamentary regime (Colombo Reference Colombo2010) with a very restricted census. In reality, the issue is complex because the Italian regime was one in which the king retained a strongly interventionist role in moments of crisis, as was the case, for example, with the choice to side with the Entente in the First World War. The role of the king, the head of state, although characterised by understatement, was, by statute, absolutely crucial in foreign policy (Barbera Reference Barbera2010, 42). There was, moreover, a circularity between the constitutional organs, as senators were appointed by the king and lifelong appointees. Still, the person who proposed the so-called ‘infornate’ (baking) – i.e. the appointment of many senators at the same time – was the prime minister (Cattini Reference Cattini1907). The ‘infornate’ often aimed to build a favourable majority for the government in the Senate (Gentile Reference Gentile2011, 40). To complete the picture of the functioning of the Italian political system, it is worth mentioning that government representatives in the provinces (the prefects) played a very important role in the process. On this, Sidney Sonnino and Gaetano Salvemini agree: the minister of the interior led the prefectural network, and the prefects ensured that, wherever possible, the ‘ministerial’ candidate won the elections.Footnote 3 The prefect, as the provincial representative of the government, played a fundamental role in selecting candidates and mobilising resources to help pro-government candidates win – all the more so in a system of low participation (Sonnino Reference Sonnino1897, 19–20).Footnote 4

Over the decades – with alternating events – a transition towards a fully democratic system developed in Italy, one of its crucial stages being the quasi-universal suffrage reform of 1912. This article aims to analyse both the ratification process of suffrage law and its impact on the party and political system. Through an approach based on the analysis of four dimensions – fundamental charter, universal suffrage, party system and electoral law – the article highlights the destabilising elements of the political system, due to the incompleteness of the path of transition.

The article is divided into three main sections. The first aims to contextualise the challenges to the liberal representation system in Italian society and the resistance to democratisation at the end of the twentieth century. Challenges led to the aggregation of forces – all focused on the enlargement of suffrage – around which the reform of the Italian political system was built in a democratic sense. The second section analyses the multidimensional effect of suffrage enlargement on the political system: results in the structure in general, impact on the party system and the structure of the socialist vote. It focuses, in particular, on the considerable differentiation of the impact of the reform on the peninsula between the North, the Centre, the South and the islands.

Finally, in the third section, the focus is on the limits and deficiencies of a democratic transition that concentrated exclusively on one aspect of the political system – in this case electoral reform, a reform that did not include, in its transformation processes, the Albertine Statute or a substantial part of the party system (in particular the liberal system).

Democracy's challenge to the liberal world

The transition from a liberal to a democratic world did not occur through reforms of the statute but through suffrage and the electoral law. An attempt will be made here to retrace the first decade of the twentieth century by following the thread of the question of representation and the enlargement of suffrage, framing it within the power balances inside the Italian political system. The cycle that had begun with the granting of the statute in 1848 was brought to an end by the historic reforms of 1912; these reforms led, through ups and downs, to the elections of 1913, which closed the cycle and resulted in the cautious and uncertain passage from a liberal Italy to a democratic one.

The period between 1900 and 1914 (the Giolittian era) marked the end of a backward phase in the democratisation process and ended with the first elections with ‘almost’ universal suffrage – those of 1913 (Gentile Reference Gentile2011, 27–32).

The democratisation process was accompanied by the expansion of the ‘Estrema’, a coalition of parties comprised of socialists, radicals and republicans. In this coalition, the mass integration parties – the socialist galaxy first (Ridolfi Reference Ridolfi1992, 223) and the Catholics later – played a paramount role in the transformation process. The struggle between liberalism and democracy, according to Norberto Bobbio (Reference Bobbio1985), lasted for the entire period between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. So, in these decades, Italy found itself experiencing a very difficult transition from a restricted suffrage model to a universal one, based on a system of organised parties.

The encounter between Filippo Turati and Giovanni Giolitti has its origins in the polarisation between the defence of liberal prerogatives and the fight for democracy.

The challenge posed by the socialists was deeply troubling for some of the liberal elites. This discomfort stemmed from a perspective articulated by Santi Romano, who argued that individuals ‘exercise sovereignty not as is their right but as organs of the state’, in which the state must be ‘conceived as a person’, distinct from the mere representation of a class or a party, and in which the state is a ‘complete synthesis of the various social forces’ (Romano Reference Romano1909, 8–9).

Romano and Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, Mario Dogliani explains (Reference Dogliani and Ballini1997, 34), agreed that the citizen did not exist outside the legal framework determined by the state and was, therefore, incapable of transmitting representation; instead, representation belonged to each organ of the state as long as it was provided for by the constitution.Footnote 5 ‘The idea of a nation as an organic whole played a decisive role in defining sovereignty,’ Floriana Colao (Reference Colao2001, 285) emphasises; sovereignty belongs to the nation, from which any voluntary element is excluded and in which the contractual theory is largely rejected.

It was one of the leading figures of the liberal right, Sidney Sonnino, who emphasised all aspects of the question. In 1897, Sonnino published an essay in Nuova Antologia entitled ‘Torniamo allo Statuto’ (Let us return to the statute): ‘Do we want a clerical, liberal-temperate, or radical socialist Italy? We must soon choose between the three’ (Sonnino Reference Sonnino1897, 26). The turn of the century marked the fracture between two opposing ways of viewing the question of representation. In antithesis to the

egalitarian conception, an anti-egalitarian, anti-participationist one developed at the end of the century, based on the principle that society, as it is, is not endowed with any political order of its own. Therefore, constitutive representation is necessary to create that order. (Dogliani Reference Dogliani and Ballini1997, 42)

This, very briefly, is the theoretical climate within which Crispi moved, and it was for these reasons that the prime minister tried to maintain an institutional framework in which the emerging masses were kept out of the circuit of representation, or at least were strongly controlled from above. It was under Crispi's administration that, for example, the public security law was completely revised, and the concept of ‘dangerous classes of society’ was introduced into the new public order regulations.Footnote 6 The police forceFootnote 7 was then updated and modernised in its investigative capacities. Raffaele Romanelli points out that Crispi's codification provided ‘the administrative structure within which the country's social and political relations will take place up to Fascism and beyond’ (Reference Romanelli1988, 207).

There are probably two particularly significant examples of the repressive policy of this period. The first was against the Sicilian fasci, between December 1893 and January 1894, when, after a brief interlude under Giolitti, Crispi returned to power and decided to use a heavy hand to repress the revolts. In a few days, almost a hundred people died, a state of siege was declared in Sicily, and the leaders of the movement were condemned to severe punishment (Romano Reference Romano1959). The second occurred between 6 and 9 May 1898, in Milan, the head of government, the Marquis di Rudinì, being the instigator. The repression of protests over the price of bread led, according to official data, to the death of more than 80 people and the wounding of 450 (Colapietra Reference Colapietra1959). De Andreis, Turati, and Morgari were considered linked to the protest, and on 9 July, the Chamber of Deputies debated and granted authorisation, by a very large majority, to proceed against them (280 present, 207 in favour, 57 against, and 16 abstaining). Turati was sentenced to 12 years in prison (Canavero Reference Canavero1976).

With Crispi's fall, the idea that the liberal state had to defend itself against external bodies did not end. Luigi Pelloux succeeded Di Rudinì as prime minister (1898–1900). Having become prime minister, he tried to make permanent some of the limitations on freedoms introduced by Crispi (Giolitti [Reference Giolitti1922] 2019, 92). Still, he was forced to give up, mainly because of the obstructionism of the parties of the Estrema (Galante Garrone Reference Galante Garrone1973, 176–211). Faced with the impasse on 18 May 1900, the king dissolved the Chamber of Deputies and called elections for June 1900. A few days after the elections, on 29 July, King Umberto I was assassinated (Gentile Reference Gentile2011, 10). The elections of 1900 showed that, despite their efforts, the Estrema had not been stopped. As a consequence of the results, Pelloux was forced not only to abandon his authoritarian plans but also to resign.

Democratising through electoral reforms

With the beginning of the twentieth century, a long phase of profound change began in which the thrust of the massed forces, organised by and around the socialist party (Ridolfi Reference Ridolfi2000, 98), was combined with the openness of a part of the liberal world, in particular that which supported Giolitti. Together, they set out on a reforming path that led to a phase of democratisation of the Albertine institutions (Degl'Innocenti Reference Degl'Innocenti and Sabbatucci1980, 64).

To better understande the process of enlarging suffrage, however, it is necessary to take a step back. In 1882, Bill 999 (Testo Unico) of 24 September – Agostino Depretis was the president of the Council and Giuseppe Zanardelli the proposing minister – was approved, extending suffrage to all male citizens who could read and write.Footnote 8 There were three innovative principles of the new electoral legislation: ‘abandonment of the census system as the main qualification for a citizen's admission to suffrage’ (Istat 1946, 47); lowering the age limit for the active electorate from 25 to 21; and ‘expansion of the criterion of ability per se, independently of any consideration of an economic nature and with the dispensation of the literacy test’ (Istat 1946, 49). The leap in the number of people entitled to vote is remarkable – from 600,000 registered to vote in the 1880 elections to approximately 2 million in 1882. This jump, however, was profoundly uneven, because in 1900 in the North, 8.9 per cent of the inhabitants had the right to vote (without distinction of sex or age), in the South 5.2 per cent, and in the islands 3.9 per cent. The upward trend in enrolments on the electoral rolls continued until Crispi decided, with Law 286 of 11 July 1894, to revise the rules for enrolment in the lists; only in 1909 did the electorate exceed in number the level reached in 1892.

In 1889, another important reform was introduced that had a fundamental bearing on representation: the elective office of mayor on municipal councils in municipalities with more than 10,000 inhabitants – a reform extended in 1896 to all municipalities – replaced appointment by the government (Gazzetta Ufficiale 1889). At the dawn of the twentieth century, the issue of the real right to vote was still to be addressed. In the North, illiteracy rates were lower than in the South and therefore there were significantly more people registered to vote.Footnote 9 This was an important issue, which Salvemini in particular was to take up, and one on which he maintained, from his reformist position, a conflict with the Turati leadership. This disparity is expressed in the number of voters required to elect a deputy.Footnote 10

King Vittorio Emanuele III, who succeeded Umberto I, showed himself more willing than his predecessor to accept a process of transformation in a democratic sense (Colombo Reference Colombo2001, 81). The socialists were changing strategy, incorporating the issue of universal suffrage in the so-called ‘programma minimo’ (minimum programme) (Ridolfi Reference Ridolfi2000, 63) – in truth, this had been the case since the clandestine congress in Parma in 1895. The socialists also combined their economic demands with a plan for consistent democratisation of the institutions: universal suffrage, abolition of the Senate, ‘freedom of all opinions and all demonstrations’ and ‘absolute neutrality of the state in conflicts between capital and labour. Effective freedom of coalition and strike’ (Degl'Innocenti Reference Degl'Innocenti and Sabbatucci1980, 71). Even the church, pressurised by the growth of the socialists, decided, albeit with many hesitations, to change its attitude towards the recently created Italian kingdom. The beginning of Pius X's pontificate was marked by an attenuation of the non expedit that had prevented Catholics, since the time of the taking of Rome in 1870, from participating in the kingdom's political life. In essence, the pontiff agreed, in alliance with the moderate fringes of liberalism, that Catholic deputies could run for office.

In this context of profound changes, it was Giolitti, then minister of the interior in the Zanardelli government (February 1901–November 1903), who, in a speech to the Chamber of Deputies on 4 December 1901, affirmed the need for the government to show neutrality in the face of conflicts between employers and workers and argued that prefects should limit themselves to guaranteeing order, ceasing to intervene in favour of industrialists or landowners. After all, Giolitti himself recalled in his memoirs, it was impossible to turn a blind eye to the hundreds of thousands of farm labourers who were striking to try to obtain decent wages (Giolitti [Reference Giolitti1922] 2019, 114).

On 3 November 1903, Giolitti became prime minister in a government backed by the destra storica (historical right) and the sinistra storica (historical left) and with the external support of the socialists. Then began a collaboration with the socialists that, despite various hesitations and difficulties, led to the enlargement of suffrage until it became almost universal.Footnote 11 Giolitti's new course immediately bore fruit in the North, but in the South repression continued to be severe and lethal. Following the deaths at Cerignola in May 1904, at Buggerru on 4 September, and in Sicily on 11 September, the Milan Camera del lavoro (Chamber of Labour) proclaimed a general strike, which took place from 16 to 21 September.Footnote 12 Giolitti tried to avoid open confrontation, convinced that the movement would die out on its own. To take advantage of the climate of dismay, Giolitti asked the king for the dissolution of the Chamber and new elections that would be held in November 1904. Once again, the changes were significant. Despite heartfelt appeals from Critica Sociale, the journal close to the reformist wing of the Socialist Party, the parties that had hitherto stood as united candidates in the ‘group of groups’ (Critica Sociale 1904, 305) of the Estrema were divided this time. This was not just a change of strategy, even if not a definitive one, but the result of a turning point that had taken place within the radicals and had been encouraged by Giolitti,Footnote 13 part of a path that would shortly afterwards lead them to join the Sonnino government of 1906 (Galante Garrone Reference Galante Garrone1973, 376). In terms of votes, for the socialists the 1904 elections were a great success as they went from 164,000 to around 300,000 (from 12 per cent to 20 per cent) but the parliamentary group shrank from 33 to 29 deputies (Ministero dell'Agricoltura 1904).Footnote 14

The last elections with restricted suffrage were in 1909. Many of the numbers based on literacy rates had remained largely unchanged, albeit with some timid enlargement of the electoral rolls, since the 1882 reform. Great inequalities remained between various areas of Italy, ranging from 13 registered voters per 100 inhabitants without distinction of sex or age in Piedmont, to 4.7 in Sardinia (Ministero dell'Agricoltura 1904, x). And among the various constituencies, where on average 2,388 votes were needed to elect a deputy, they ranged from a minimum of 789 to a maximum of 5,225 (Istat 1946, 43–47). In the 1909 elections, the socialists changed their strategy from 1904 and, in some respects, also from that adopted in 1900. The line this time was to give their voters freedom of vote in every constituency. That is, it was proposed that they voted in the first round for those candidates who were most likely to win and who came closest to the programme (Critica Sociale 1909, 52) that had been voted for almost unanimously in February 1909 and that largely revolved around the enlargement of the suffrage and the introduction of proportional counting. The success of the changes was undoubted, even if the electorate lost a few points in percentage terms, it grew in terms of votes: the parliamentary group grew from 29 deputies to 41. The electoral agreement between the parties once united in the ‘group of groups’ had borne fruit, but once again had punished the socialists more than others, including the republicans and radicals themselves.Footnote 15

‘Almost’ universal suffrage

The debate on the enlargement of suffrage was long and complex. Turati was certainly in favour, but without great enthusiasm and with some perplexity (Ridolfi Reference Ridolfi2000, 62–73). He was concerned about the backwardness of the South and about a possible conservative vote from the new eligible voters, and he was aware that, at least in the North, there was a strong support base for the socialist party. In the vanguard of those who were most convinced were Salvemini and Anna Kuliscioff (Kuliscioff Reference Kuliscioff1908, 244). Those in this vanguard were not against the enlargement of suffrage per se, but many in liberal circles were sceptical, and Sonnino, who had previously spoken out in favour, at least in principle (Giornale d'Italia 1905), was against it.

Gaetano Mosca, in a long editorial in the Corriere della Sera of 17 February 1906, expressed many perplexities about a project that, in his opinion, was supported ‘exclusively by those who ascribe to the policies of the republican and socialist parties’, in particular the most extreme fringes, and that therefore ‘at some special time, could benefit those who preach the immediate and revolutionary implementation of the principles of collectivism’. In his opinion, the project would also prove harmful to the South, so much so that he was ‘convinced that the proposed remedy would in any case aggravate the evil, rather than mitigate it’ (Mosca Reference Mosca1906). Luigi Luzzatti, president of the Council between 31 March 1910 and 29 March 1911, accelerated the debate. The new government was born out of an alliance between the historical right, the historical left and the radicals, and on an agreement whose main objective was to enlarge electoral suffrage and whose external supporters included the socialists. As early as February 1910, in fact, a committee had been set up in the Chamber of Deputies to organise a mobilisation in the country to accelerate the implementation of the reform (L'Avanti! 1910) and on 1 May 1910 the socialists launched a large mobilisation in favour of universal suffrage (Vigezzi Reference Vigezzi1972). The Luzzatti government became deadlocked both on the reform of the Senate, on which the upper house expressed an unfavourable opinion, and on the reform of the electoral law (Ballini Reference Ballini2007, 129). The negative opinion of Giolitti, who was in favour of a more decisive enlargement, weighed most of all and determined the end of Luzzatti's administration.Footnote 16

With the fall of Luzzatti, Giolitti's name circulated as his successor; this transition, however, immediately appeared different from the others. On 22 March 1911, the Corriere della Sera floated the hypothesis that the socialists might take part in the government: ‘reports affirm that, in the first steps to resolve the crisis, Giolitti will not rule out turning to the socialists’ (Corriere della Sera 1911a). This hypothesis was then discarded as early as the following day (Corriere della Sera 1911b) but was updated by another piece of news on 23 March when ‘around 11 o'clock at Montecitorio the news spread that created something of a sensation: that Leonida Bissolati had been received in the morning by the king’ (Corriere della Sera 1911c). While the news of the invitation was confirmed, the visit to the king was not confirmed, however, and it was ignored for reasons of political expediency. On 31 March, Giolitti presented the government and its programme. The Corriere della Sera mocked Giolitti's sudden change of mind on suffrage, evidently due to negotiations with both the radicals and the socialists: ‘Giolitti had hitherto shown himself to be a staunch opponent of universal suffrage, which he had even mocked from the government benches, pointing it out as “illiberal”’ (Corriere della Sera 1911d). Finally, the socialists, while refusing to become part of the new executive, guaranteed external support: the majority in the chamber was 340 in favour and 88 against.

In essence, the enlargement of suffrage to become universal meant making illiterate people vote, since the law passed in 1882 had set the criterion of being able to read and write. Widespread mistrust remained. The Nuova Antologia, for example, pointed out that Giolitti's reform project would result in a majority of voters who could not read and write and were therefore more likely to be manipulated (Nuova Antologia 1911). In June 1911, debates began in the Parliament offices on the proposal presented by Giolitti on 9 May of that year. Many issues were discussed in those months. In addition to suffrage, allowances for parliamentarians and the nationalisation of insurance, Giolitti also presented a plan for the annexation of Libya and thus a war against the Ottoman empire. This was a fundamental step because the resumption of Italian expansionism determined the crystallisation in fieri of a bloc – that of nationalists, futurists, conservatives and a specific model of representation: the corporative. The decree for the annexation of Libya was approved on 5 November 1911 and converted into law in February 1912. On 25 May, the Chamber of Deputies approved the enlargement of the suffrage: there were 284 in favour and 62 against. La Stampa published the news only on page 4; the front pages of the major newspapers concentrated on the Italo-Turkish war.

The effects of ‘almost universal’ suffrage

The elections of 1913, the first with enlarged suffrage, must be set in a more complex context. On the one hand, the liberal groups, the pivot around which the ‘costituzione materiale’ (material constitution) (Mortati [Reference Mortati1940] 1998) of Albertinian Italy revolved, had their strength reduced from election to election, with the factions furthest to the right suffering in particular. On the other hand, the party system could benefit from the support of new formations that entered the ranks of those involved in government majorities, with those coming up from subordinate positions able to assume a central role; I refer, in particular, to the Catholics. Left out of any government were the socialists, the party that strengthened its entrenchment from election to election.

The effects of suffrage enlargement must be understood within the interaction of at least four dimensions: the fundamental charter, universal suffrage, the party system and electoral law. In the transition between 1911 – i.e. shortly before the approval of ‘almost universal’ suffrage – and November 1919, the pattern of the functioning of the Italian political system was profoundly altered in three of these dimensions, without, however, these changes becoming structural and turning into an overall reform of the Albertine Statute.

Data from elections up to 1913 are often contradictory and incomplete. Official statistics do not mention parties. Central to this are the studies of Alessandro Schiavi, who devoted two essential texts to the subject in La Riforma Sociale (Schiavi Reference Schiavi1909, Reference Schiavi1914b). However, these aggregate data needed to be broken down into a series of dimensions that could give greater depth to the analysis. The database used in this article includes the elections of 1909 and 1913 divided into geographical areas (North, Centre, South and islands), constituencies, voters per constituency, votes for the winner, votes for the socialist candidate, the difference between the first candidate and the second, the winner's party, runoffs and constituencies with single candidates. The most complex part was associating the candidates with a party, focusing primarily on socialist candidates. The results were then divided into three dimensions: results in the structure in general, impact on the party system, and the structure of the socialist vote.

Results in the structure

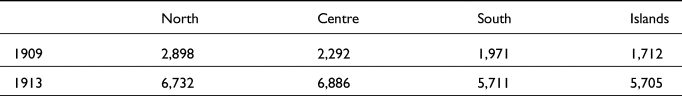

The two-round majority electoral system and the number of constituencies in the 1913 elections remained the same as in the 1909 elections. Clearly, the 1913 elections saw a very substantial increase in the number of voters, with very different effects in the northern and southern parts of the country. The enlargement of the number of voters per constituency from an average of 5,000 to 15,000 inevitably implied a reduction in the ability to control the entire electoral process on which the liberal system had been based, which was, as is well known, based on three characteristics: unstructured formations, majority constituencies, and often client–list relationships within the constituency between the MP and the voters. Enlargement and the consequent exponential increase in the number of voters produced, as Schiavi explains, ‘an earthquake in the balance within the social classes with the right to vote’.Footnote 17 It was in the South and on the islands that the effects of enlargement were felt most strongly, with growth in the number of electors of 376 per cent and 460 per cent respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Percentage growth of electors and voters (1909–13)

In the North, the number of electors grew ‘only’ by 240 per cent (Table 1). Abstention remained broadly similar in the two electoral rounds of 1909 and 1913, but even here there was a cleavage between the North, where abstention halted at 30 per cent, and the rest of the peninsula, where it exceeded 40 per cent. The number of votes needed to elect an MP grew exponentially, more than doubling in the North (from around 3,000 to almost 7,000) and tripling in the South and the islands (from around 2,000 to 6,000 and from 1,700 to 5,700, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2. Average number of votes required to elect a deputy (1909 and 1913)

These numbers indicated a central fact: ‘almost’ universal suffrage profoundly impacted the elections, making them much more competitive than in 1909. Meanwhile, the number of runoffs increased (84 to 101), especially in the South (Table 3), from 11 to 19. The number of single-candidate constituencies decreased dramatically (from 80 to 41), again substantially throughout the peninsula but still with a particular incidence in southern Italy, where they fell from 36 to 18, and in the islands, where they fell from 15 to 6.

Table 3. Election data comparison (1909 and 1913)

The distance between the elected candidate and the first of the runner-up also decreased. The number of competitions where the difference between first and second was less than 25 per cent rose in the North from 53 to 68, in the South from 26 to 35 and in the islands from 7 to 12, remaining substantially unchanged in the Centre. The electoral competition was more open, especially in the South, where, between ballots and narrow victories, the constituencies where the result could have been different rose from 37 to 54 and in the islands from 12 to 18.

A total of 146 deputies, about 30 per cent, were elected for the first time,Footnote 18 a higher figure even than in the 1892 elections, which had introduced the single-member constituency. On the other hand, the revision of the electoral constituencies established in 1891 was not implemented, even though the electoral geography, which at the time of the reform provided for a consistent number of electors/seats, had now changed radically. With industrialisation, the large cities’ populations grew exponentially: Milan + 187 per cent, Catania + 206.4 per cent, Rome + 189.4 per cent and Turin + 166.4 per cent, to list just a few examples.Footnote 19 In a system of uninominal constituencies, this led to increasing inequality between constituencies.Footnote 20 The first elections with ‘quasi-universal’ suffrage had resolved the divide between North and South but not yet the imbalances between country and city (Istat 1946, 103).

Impact on the party system

The formations that had represented the nucleus around which all governments had been built were reduced in strength once again in the 1913 elections. To follow the methodology used by Schiavi himself, we can see how liberal and democratic deputies, who in 1909 were still widely in the majority in all areas of Italy, with peaks of 85 per cent in the South, in the run-up to 1913 were considerably reduced. In the North, they accounted for just over 50 per cent; in the South, they fell from 85 per cent to 70 per cent; in the islands, they fell from 74 per cent to 52 per cent. However, the independent participation of Catholics was strengthened, another fact that will later be of great importance, just as the nationalists enjoyed some success. In essence, governing became more difficult for the old liberal class. It was therefore necessary to broaden the base of government; from this point of view, some of the old extreme parties were absorbed. The radicals strengthened particularly in the South. For the first time, the reformist socialists presented themselves in the elections, and even for the republicans, the results were not entirely negative.

The forces of the governing left in the South and the islands rose from 11 per cent and 21.5 per cent to 22 per cent and 41 per cent, respectively (Table 4). Giolitti wrote in his memoirs, published in Reference Giolitti1922 ([Reference Giolitti1922] 2019, 208), that the 1913 elections had not produced a seismic change. Still, in reality, they had introduced a new dynamic in which the confrontation was between all the constitutional forcesFootnote 21 on the one hand, with their deep internal divisions, and the class parties on the other.Footnote 22 The socialists obtained 79 deputies.Footnote 23 The Catholic deputies, already present, grew in this round from 16 to 29 and from 73,000 votes to 300,000. Another sign of the changes, due in this case to the war in Libya, was the affirmation, albeit still contained, of the nationalists, who presented themselves for the first time at the elections with their lists and managed to elect five deputies, including Luigi FederzoniFootnote 24 and Piero Foscari.

Table 4. Members of the Chamber of Deputies by percentage (1909 and 1913)

Socialists

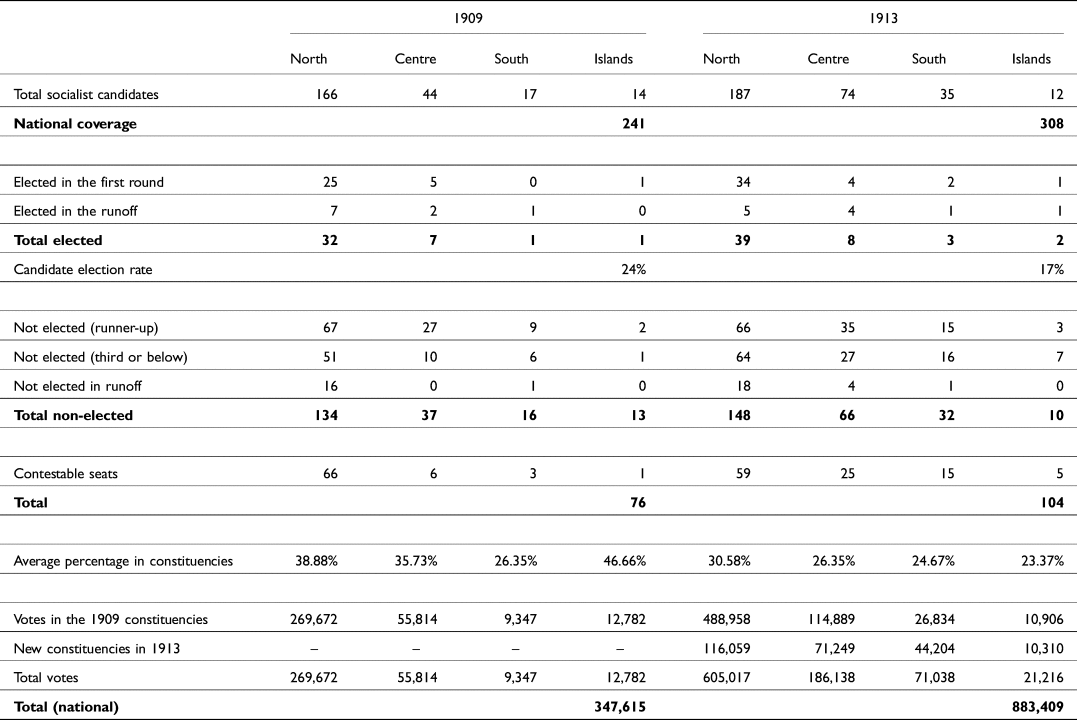

The SocialistsFootnote 25 deserve a separate examination because of their more or less effective character as an anti-system party.Footnote 26 The question of the impact of the enlargement of suffrage on the socialists and the impact of voting for the socialists in the party system, in general, is complex and cannot be measured solely by the number of deputies elected in the various constituencies, a figure that does not reflect the actual weight of the change. A more structured analysis is required. From 1909 to 1913, the number of candidates throughout the territory grew consistently, from 166 to 187 in the North, from 44 to 74 in the Centre, and from 17 to 35 in the South, while it decreased from 14 to 12 in the islands. At the national level, socialist candidates increased from 34 per cent to 60 per cent of seats. The number of candidates and the victory rate per constituency fell from 24 per cent of seats won in 1909 to 17 per cent in 1913 (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparative summary of the socialist vote structure (1909 and 1913)

If we consider the constituencies where the socialist candidate came second or lost in the runoff, they grew from 122 to 142 overall. While the percentage obtained in general elections changed little, around 18 per cent, if we take into account only the results obtained in the constituencies where there were socialist candidates, the percentages were around 30 per cent, with no significant difference between 1909 and 1913. The growth in the number of voters was below the growth in general votes if one considers the constituencies with socialist candidates in 1909. These percentages are broadly similar if those constituencies already occupied in 1909 are compared to those of 1913. The areas with the highest growth in votes were undoubtedly the Centre, where there was an increase from 55,814 to 186,138, and the South, where there was an increase from 9,347 to 71,038 (Table 5). One weakness of the socialists was their capacity to aggregate votes in the second round. In the North, where a second round with a socialist candidate was more frequent in 16 constituencies, the socialist candidate lost; in only 7 did he win. In 1913, the ratio was 13 lost and 5 won.

Conclusion: an incomplete democratic system

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, the Italian political system underwent a profound process of transition from a liberal to a democratic system – a transition that focused in large part, though not solely, on the enlargement of the suffrage, which, with the 1912 reform, became ‘almost’ universal. To understand how the Albertine political system changed its intimate and implicit rules throughout the political reforms, we adopted a multidimensional analysis in which we sought to analyse the mutual impacts of the enlargement of the suffrage, the electoral law and the transformation within the party system.

The first consequence that must be pointed out was that the 1913 elections saw a much higher rate of competitiveness than the 1909 elections. There were more ballots and fewer constituencies with a solitary candidate. The second is that, even if somewhat veiled, the organisation of around 15,000 members in each constituency required a far greater capacity for mobilisation and professionalisation of politics than the liberal leaders from Giolitti to Salandra were used to. In this sense, mass integration parties, organised throughout the territory, with coherent programmes and a developed propaganda apparatus, were the only ones able to compete. Of course, the issue of the mass party organisation was less straightforward than it appeared. Otherwise, if it were so consequential, the socialists – the only organised party at the time – should have achieved a much more significant victory. L'Avanti! spoke of a triumph, but, in reality, that triumph had not yet been achieved. Indeed, affirmation in the new constituencies was crucial, but with the double-round system, it was easy for liberal formations to aggregate anti-socialist forces in the second round. Furthermore, the field of liberal forces was far from homogeneous, divided internally between more progressive and more conservative groups (Adinolfi Reference Adinolfi2022, 90). However, one fact would have a fundamental effect on the forthcoming elections: the inability of the liberals to organise themselves autonomously and consistently within the rules that had sprung up from a rapidly changing society. The forces that had been part of various government coalitions in the past avoided a debacle, thanks to an agreement with the Catholics, who were more capable of mobilising the electorate thanks to one of the most widely distributed networks in the territory: that of the churches. Underlying an agreement that was a rearguard action – especially if one considers that part of Italian politics that had, until then, been characterised by a strong anticlericalism – was the concern about a probable affirmation by the socialists. In 1909, socialist candidates had already come second in many constituencies. The unwritten and unofficial pact (Gentile Reference Gentile2011, 244) that Giolitti made with Vincenzo Ottorino Gentiloni, president of the Catholic Electoral Union, thanks to which the non expedit was suspended in 367 out of 508 constituencies (Laschi Reference Laschi1990, 124), allowed a liberal Italy to survive for a few more years. According to this agreement, Catholics would support liberal candidates in exchange for support on strictly Catholic issues, such as divorce or public schools. It was only in this way that the various liberal formations, together with conservative Catholics, managed to maintain a majority.Footnote 27

Thus, the elections of 1913 were both the last of an era and the first of a new one in which the liberal world showed itself to be increasingly divided and dependent on the support of the Catholic vote to be able to contain and confront the growth of the socialists (Noiret Reference Noiret, Ballini and Ridolfi2002). Between 1909 and 1913, there was a change from the dichotomy between ‘ministerial’ and ‘opposition’ (Schiavi Reference Schiavi1909) within the liberal field, to the dichotomy of ‘conservative parties’ in the liberal field and ‘class opposition’Footnote 28 on the part of the socialist party. With the enlargement of suffrage, there was also a change in the voting dynamics in the South and the islands. The safe seats – created by a reserve of a few votes controlled by the prefects, as Sonnino and Salvemini denounced – became a phenomenon that did not disappear altogether but inevitably decreased drastically, with a strong impact on the government's ability to secure solid majorities.

A reading of the data allows us to state that the system of liberal formations had managed to win the battle but was in danger of losing the war. There was, however, awareness of this point. In 1914, in conjunction with the birth of the Salandra government, the idea of forming a ‘Fascio liberale’ (Corriere della Sera 1914) began to make headway: that is, the idea of promoting, through the new majority, the unity of a group antithetical to the progressive liberals – the so-called ‘Nittiani’.Footnote 29 The government crisis that followed the defeat at Caporetto in 1917 brought Vittorio Emanuele Orlando to the presidency of the Council and, in the Chamber, a new group: the Parliamentary Fascio of National Defence. It is impossible to go over all the complex events of the Parliamentary Fascio. However, the fact remains that at the dawn of the 1919 elections, after two years of discussions, conventions and manifestos, the issue of the conservative party had not yet been resolved. There was a widespread awareness of its necessity, on the one hand, but then the logics to which liberal leaders were accustomed had prevailed. What completely changed the game was the birth of the People's Party in January 1919, when the electoral law had not yet been changed to proportional. This new party aimed to recover the Catholic vote that had converged on the liberal formations in the 1913 elections.

In essence, the liberal world, in two dimensions – those of the Albertine Statute and the party system – had failed to cope with the significant transformations of a political system based on the large numbers involved in universal suffrage. The end of the non expedit, the birth of the People's Party and the lack of a mass conservative party were at the root of a profound imbalance in the political system, highlighted by the high abstention rates and a vacuum destined to be filled.

Financial support

This paper was supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia – FCT).

Goffredo Adinolfi is a contemporary history researcher at the Centre for Research and Studies in Sociology at the Lisbon University Institute. He holds a PhD in Contemporary History from the University of Milan (2005). His research interests mainly focus on anti-liberal thought: fascism and populism. On this topic he has published Ai Confini del Fascismo. Propaganda e consenso nel Portogallo salazarista (Franco-Angeli, 2007), ‘Political Elite and Decision-making in Mussolini's Italy’ (in Ruling Elites and Decision-making in Fascist-Era Dictatorships, edited by António Costa Pinto, 2009), ‘The Institutionalization of Propaganda in the Fascist Era: The Cases of Germany, Portugal and Italy’ (European Legacy, 2012) and ‘Continuities and Discontinuities in the Processes of Elite Recruitment: The Italian Political Field between Authoritarianism and Democratic Regime’ (Topoi, 2022).