Introduction

Background

Disasters are chaotic events characterized by health needs that exceed existing capacities, requiring outside health care assistance. This assistance can be provided by national and international disaster health care responders. International disaster responders can be deployed by governmental agencies and non-governmental organizations. Their work is characterized by a lack of resources (eg, time, materials, or capacity). Difficult decisions must be made in often dangerous and challenging contexts. Choices must rapidly be made regarding whom to treat first, who must wait, and how to make optimal use of the limited resources available. The morally challenging choices add an additional burden to the work in an already stressful environment filled with risk factors for traumatic stress and burnout. Reference Michel1 To support responders, there are a range of policies and legislations to guide their work, 2–Reference Friedman, Warfe and Mwiti4 as well as ethical principles and documents on medical ethics in disasters. Reference Rességuier5 These documents, however, outline general policies that are difficult to apply in practice. They provide limited guidance for specific situations in choosing the “best solution” for whom to treat and whom to leave. In reality, there are few, if any, specific training programs to support ethically informed decision making in disaster settings. Algorithms for triage within mass-casualty situations are intended to guide the personnel in decision making, to sort and prioritize among disaster victims. Reference Tannsjo6 However, it remains unclear how disaster health responders react and cope with the difficult decisions they must make and how they morally rationalize this. In this field, there is a significant knowledge gap between ethical theory and its practical implementation. Reference Tannsjo6 Further, decision making within disasters is not limited to mass-casualty incidents. Various challenges related to care situations where responders are hindered to follow inner moral values are met in normal health care, but they are highly intensified in disaster settings. Reference Leider, DeBruin, Reynolds, Koch and Seaberg7 This means that responders must make decisions that they are often ill-prepared for. Reference Rességuier5 They face moral dilemmas in which “each course of action breaches some otherwise binding moral principle.” Reference Kälvemark Sporrong8 When a responder is confronted with choices that, due to external factors, compromise their moral consciousness, it may result in feelings of frustration, powerlessness, anger, and remorse. This inner conflict has been labelled “moral stress,” Reference Lutzen, Cronqvist, Magnusson and Andersson9 which is (theoretically) separated from standard stress theories, which include the reaction related to an imbalance between demands and resources. Reference Hessels, Rietveld and van der Zwan10 The stressor related to moral stress is an ethical problem, and the consequences can cause a stress reaction, depending on how the stressor is addressed by the individual. Reference Kälvemark Sporrong8,Reference Lutzen, Cronqvist, Magnusson and Andersson9 This can be viewed as a reaction that may be of help for the individual to identify moral problems, but can, if not adequately dealt with, develop into what has been labelled “moral distress.” Reference Zuzelo11 However, the difference between moral stress and moral distress is differently interpreted within the literature. The term moral distress was defined by Jameton in 1984 to describe the psychological reaction to situations when the individual knows what is morally right, but is unable to act accordingly. Reference Jameton12,Reference Jameton13 Moral distress research originated in nursing care, but it also involves other professions. Reference Kälvemark, Höglund and Hansson14

If moral distress is left unaddressed, an imbalance between the individual’s inner convictions and overt behavior might affect core values and erode personal moral integrity, which may contribute to burnout and psychological distress among disaster responders. Reference Thomas and McCullough15 The potential of cascading effects of moral distress may lead to not only individual suffering, but also sick leave and high drop-out rates, causing high costs for society. Reference Lopes Cardozo, Gotway Crawford and Eriksson16

Psychological distress was reported among health care responders during the Ebola outbreak in 2014-2015. It was perceived as morally difficult to isolate the infected while not having resources to offer care for them. Clinical care was too dangerous and even considered futile. Reference Rubin, Harper and Williams17,Reference von Strauss, Paillard-Borg, Holmgren and Saaristo18 The shift away from patient care caused moral concerns that the staff was not adequately prepared for. This event underscores that disaster responders must be well-trained and mentally prepared to manage morally challenging situations. To do so, more systematic knowledge is needed about the type and extent of moral challenges that responders face in disasters, and how they deal with them. Further, disaster responding organizations have considered increased drop-out rates and sick leaves as consequences of moral distress. Studies within the military discipline have also highlighted the issue of moral implications as it seems to affect their employees’ well-being. Reference Agazio and Goodman19 Therefore, initiatives have been taken to address and understand the impacts of moral distress and its consequences for responders. Since there is unclarity among the different definitions, a first step is to understand the concept of moral distress and its interlinkages within the literature related to disaster responders.

Aim

The aim of this study is to elucidate how the concept of moral distress among disaster responders is defined and explained in the literature.

Method

To optimally address the research aim, a scoping review design was chosen. This method is used to systematically map the existing literature in the area of interest and to address broader topics rather than providing a specific answer to a narrow research question. It provides a systematic approach and allows inclusion of both unpublished documents and peer-reviewed papers with the aim of identifying gaps in the research addressing a certain subject area. Reference Grant and Booth20–Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien22 The academic databases CINAHL (EBSCO Information Services; Ipswich, Massachusetts USA); Ethicsweb (European Ethics Documentation Centre; Europe); PsycINFO (American Psychological Association; Washington DC, USA); PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA); and Web of Science (Thomson Reuters; New York, New York USA) were queried with search terms displayed in Appendix 1 (available online only), adopted according to database format. Google Scholar (Google Inc.; Mountain View, California USA) and websites related to disaster and humanitarian response were searched to identify the potential size of available research. The number of references added manually through reference lists in key-note articles was substantial. Through searches on Google Scholar, humanitarian networks, and organizations’ websites, documents such as thesis works, book chapters, and posters were found, which are not always available through academic databases. The most relevant organizations’ and networks’ databases were searched, such as World Health Organization (WHO; Geneva, Switzerland), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; Geneva, Switzerland), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF; Geneva, Switzerland), Research Unit on Humanitarian Principles and Practices of MSF Switzerland (UREPH; Geneva, Switzerland), Humanitarian Health Ethics Research Group (HHE; Hamilton, Ontario, Canada), and the disaster bioethics network through the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST; Brussels, Belgium). When searches on moral distress or moral stress rendered no hits on the websites, the searches were expanded with the search term “ethics” to capture documents including ethical issues. These documents were then screened for eligibility. An overview of the search strategy is displayed with the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram.

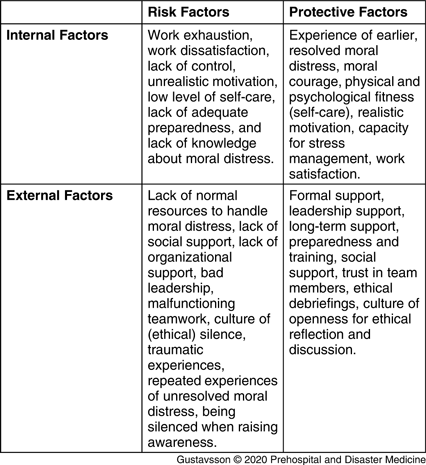

The inclusion criteria included documents with the phrasing moral stress, moral distress, ethical stress, or ethical distress concerning disaster responders or humanitarian workers within disaster response and/or humanitarian contexts. A total of 27 documents were selected for screening using Rayyan software (Qatar Computing Research Institute; Doha, Qatar) to label the references according to descriptions of moral distress, and documents not eligible according to the inclusion criteria were excluded. 23 The final selection resulted in 16 documents, listed in Appendix 2 (available online only). They were analyzed and collated according to their definitions of moral distress or according to their descriptions of moral distress. The described areas of moral challenges, when facing moral stress, are summarized in Table 1. The described factors that affect moral distress were structured according to risk, protective factors, and derived consequences, which are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1. Summarized Areas of Moral Challenges within Disaster Response and Humanitarian Contexts

Table 2. Factors Affecting Moral Distress among Disaster Responders

The terms “disaster response” and “humanitarian assistance” or “humanitarian workers” were interchangeably used to describe the work. Neither “humanitarian assistance” nor “humanitarian workers” were well-defined, and the difference between the two, if any, was not well-explained. It seems that disaster response describes the work of salaried governmental staff, while “humanitarian” is used to describe assistance delivered by volunteers working for neutral, independent, and impartial non-governmental organizations. In this study, a separation between the two was not made since the difference between them was not consistent or clear in the literature. Disaster responders are described in this study as individuals working as health professionals and support staff to provide international disaster assistance, including governmental staff and humanitarian workers. 24 The term humanitarian workers will, in this study, be defined as responders of humanitarian organizations.

Report/Result

Definitions of Moral Distress

In the 16 documents, it was found that moral distress, moral stress, and ethical distress are expressions used in a concomitant way, describing similar phenomena. Two of the documents used “moral stress” as an overall expression, Reference Nilsson, Sjöberg, Kallenberg and Larsson25,Reference Noutsou26 one document used “ethical distress,” while others drew a distinction between moral stress and moral distress. Reference Durocher, Chung, Rochon, Henrys, Olivier and Hunt27 “Complex humanitarian distress” was also mentioned, describing ethical distress among humanitarian workers. Reference Nordahl28

A majority of the definitions and phrasing of moral distress refered to Andrew Jameton’s definition: “Moral distress arises when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constrains make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.” Reference Jameton12,Reference Jameton13 Raines later expanded on Jameton’s definition of moral distress: “(Moral distress) occurs when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional or other constraints make it difficult to pursue the right course of action.” Reference Raines29 This definition was referred to in one document, Reference Noutsou26 while four other documents Reference Nilsson, Sjöberg, Kallenberg and Larsson25,Reference Gotowiec and Cantor-Graae30–Reference Smith, Ahmed and Smith32 referred to a combination of definitions. These combinations referred to Jameton’s definition, and later broader definitions, such as this definition by Kälvemark, Höglund, and Hansson: “Traditional negative stress symptoms that occur due to situations that involve an ethical dimension and where the health care provider feels she/he is not able to preserve all interests at stake.” Reference Kälvemark, Höglund and Hansson14 These two later definitions were expanded to reach beyond moral dilemmas; that is, situations where it is (nearly) impossible to do what is morally permissible (or right), including situations that bring about any type of moral challenge. Reference Jameton13,Reference Kälvemark, Höglund and Hansson14,Reference Raines29,Reference Radzvin33 Studies and documents that focused more on the emotional aspect had used the definition developed by Wilkinson: “The psychological disequilibrium and negative feeling state experienced when a person makes a moral decision but does not follow through by performing the moral behavior indicated by that decision.” Reference Wilkinson34 Wilkinson’s definition was narrower than the others by merely including akrasia (weakness of will) as the defining feature of moral distress: that moral distress is only about failing to act on a moral decision.

In Boswell’s study Reference Boswell35 on mental health and moral incongruence in disaster/humanitarian response, moral distress was described as one of the labels of psychological burden of moral compromise using Corley’s definition: “[The] uncomfortable psychological disequilibrium that occurs as a result of unethical performance due to obstacles such as time, supervisory conflict, legal parameters, organizational policy, and hierarchal relationships.” Reference Corley36

The chapter “Ethics of Healthcare in Disasters and Conflict” in the ICRC’s field guide on Management on Limb Injuries during Disasters and Conflicts described moral distress as: “When one knows the ethically correct action, but feels powerless to take that action,” 37 without referring to any specific definition.

The referenced theories and definitions of moral distress were developed from research on health care in high-resource settings. Four of the authors had developed their own concepts or developed novel theoretical models from their findings. Documents that did not state a definition or theory of moral distress nevertheless described factors that contributed to moral distress and proposed novel tools to address moral challenges. Appendix 3 (available online only) summarizes the concepts of moral distress as described in the included literature.

Decision Making – Moral Uncertainty, Moral Reasoning, and Moral Costs

In the book Humanitarian Action and Ethics, the author described moral distress as derived from decisions related to the micro level; that is, when a health care provider faces challenges in delivering care to individuals. Reference Smith, Ahmed and Smith32 Studies by Hunt and colleagues focused on the concepts of moral uncertainty and difficult moral reasoning coupled to decision making as sources of moral distress. In one study, they explored dilemmas related to decisions on whether to provide care outside of professional competency. Situation analysis and retrospective debriefing were two aspects highlighted that could assist professionals in performing informed ethical decision making. Reference Hunt, Schwartz and Fraser38 In another study by Hunt, participants reported that moral uncertainty and anxiety lead to distress, primarily derived from complex ethical situations. Reference Hunt39 A six-step process was later proposed by Hunt that aimed to give individuals theoretical knowledge to better assess and manage ethical challenges. Reference Hunt40

Moral cost was another concept that Hunt and colleagues used to describe the result of making decisions or actions that trespass on one’s own moral values. The concept of moral cost is similar to the concept of moral injury. Reference Nordahl28,Reference Boswell35 Hunt, Sinding, and Schwartz described tragic choices as derived from situations of decision making without a “good option,” which leads to moral costs. Reference Hunt, Sinding and Schwartz41

Clashes with Perceived Ideal or Identity

According to three documents, moral distress is centered around the inability of responders to live up to their professional and personal ideals. Schwartz, Sinding, and Hunt described situations in which responders, health care workers, and agencies in humanitarian work “…do not help as intended, and instead impos[e] harm on patients and/or local staff and health systems” as contributing to moral distress. Reference Schwartz, Sinding and Hunt42 Noutsou suggested that issues related to not being able to maintain professional and personal contribution as intended affect moral distress. Reference Noutsou26 In an article by Schwartz, et al, moral distress among Canadian health care workers was described as: “Ethical challenges which create impacts on both professional and personal identity.” Reference Schwartz, Hunt and Sinding43 High expectations, lack of control, and being unprepared for restructuring priorities were factors contributing to moral distress. Reference Schwartz, Hunt and Sinding43 In their paper of nursing ethics and disaster triage, Wagner and Dahnke suggested that moral distress is developed from situations in disasters in which the nurse “has to ignore the instincts of helping and nurturing patients.” Reference Wagner and Dahnke44

Organizational Constraints

The decisions and the level of support provided by the responders’ organization influenced the development of moral distress among responders. In a study of the European migration flow, the workers’ levels of moral distress were increased by the organization’s lack of adaption to a new political context, rather than by a lack of resources. Reference Noutsou26 In another document, uneven allocation of aid and lack of information within the organization to effectively deliver response was reported to cause ethical distress among responders. Reference Durocher, Chung, Rochon, Henrys, Olivier and Hunt27 The consequences derived from uneven provision of aid have been testified by humanitarian workers not in direct contact with the affected individuals, and implicates that moral distress is also experienced by non-medical responders. Reference Nordahl28 One study reported that increased geographical distance to the suffering generated emotional detachment and made individuals less prone to moral distress, while individuals directly confronted with the consequences of decision making seemed more prone to both acute and cumulative stress reactions. Reference Nilsson, Sjöberg, Kallenberg and Larsson25 In a study by Gotowiech and Cantor-Graae, worsened stress reactions were reported by health care workers who felt they were silenced and ignored when they reached out for guidance when encountered with moral challenges. Furthermore, the authors implied that increased knowledge of moral distress in organizations is crucial to develop guidance and training frameworks. Reference Gotowiec and Cantor-Graae30 The MSF organization also emphasized the importance of increased knowledge, as fieldworkers have urged better support to manage moral and psychological distress. Reference Biquet, Chang and Salvador31

Areas of Moral Challenges – Situations that Might Result in Moral Distress

Moral challenges are situations within a disaster response where the responder faces difficulties acting according to their moral values. These situations were also described by Hunt as complex ethical issues. Reference Hunt39 However, these situations result in a stress reaction, labelled as moral stress in two documents, Reference Nilsson, Sjöberg, Kallenberg and Larsson25,Reference Noutsou26 while other documents labeled this stress reaction as moral distress or ethical distress. Suggested indicators of moral distress were how the individuals perceive their moral responsibilities and how the context is interpreted, which determine the severity of the situation when faced by moral challenges. Reference Noutsou26 Contextual challenges were described as external factors that hinder the responder from acting according to what is perceived as right, without trespassing on the autonomy and dignity among patients. Reference Hunt, Schwartz and Fraser38 These decisions must be made by responders during events of mass casualties when it is necessary to select patients who might benefit the most by medical intervention. Choosing between treating individual patients in-need versus focusing on public health care needs are also challenges that health care workers face. 37 An overview of described moral challenges within disaster response and humanitarian contexts is shown in Table 1.

What are the Consequences?

Individuals are guided by their moral values to make decisions in morally challenging situations. Reference Hunt40 Repeated and unaddressed moral distress seems to affect the moral compass and the identity of individuals, which might lead to decreased capacity to follow and act upon personally held moral values. Reference Boswell35 Moral residue was described as lingering moral costs and a cause of strong feelings of anxiety. Reference Hunt, Sinding and Schwartz41 This was also described by Durocher, et al as leading to ethical distress, which was suggested to be highly likely in situations in which all options available to an individual demand something of ethical importance to be surrendered. Reference Durocher, Chung, Rochon, Henrys, Olivier and Hunt27 The MSF research unit (UREPH) had highlighted a pattern of moral distress only becoming visible for the organization when it has resulted in psychological distress. It has also been suggested that repeated and unresolved moral distress leads to moral residue, which further leads to negative psychological consequences. Reference Biquet, Chang and Salvador31 Gotowiec and Cantor-Graae suggested that these psychological consequences lower the responders’ capacity to provide care of high quality. Reference Gotowiec and Cantor-Graae30

What Makes it Worse? Risk Factors

The risk of moral distress depends on the severity, duration, and a repetitive encounter of morally challenging situations. Reference Nordahl28,Reference Smith, Ahmed and Smith32,Reference Elit, Hunt, Redwood-Campbell, Ranford, Adelson and Schwartz45 Work exhaustion and work dissatisfaction with a lack of control is evidently a destructive factor for moral distress. Furthermore, a lack of knowledge and preparation in managing moral challenges leads to increased risk in developing moral distress. Reference Schwartz, Hunt and Sinding43 Being unprepared for applying an ethical approach that is different from the four traditional principles (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficent, and justice) was described by Wagner and Dahnke as causing moral distress. Reference Wagner and Dahnke44 Another negative factor mentioned by Gotowiec and Cantor-Graae was the lack of support from co-workers and managers in the team when reaching out for help on ethical issues. Reference Gotowiec and Cantor-Graae30 A lack of formal and informal support during and after the response increased feelings of isolation. Isolation and lack of recognition of moral distress can result in a higher risk of developing negative psychological consequences such as burnout and secondary traumatization. A responder’s altruistic motivations being overrun by the situation at hand is another risk factor for moral distress that has been noted particularly among humanitarian workers. Reference Nordahl28

How Can Moral Distress be Alleviated? Protective Factors

Resolved moral challenges may lead to confidence and growth within responders. Reference Nordahl28 However, addressing and alleviating moral distress depends on available internal and external resources. External resources can be formal and informal, such as leadership support, support from the team, psychological support, and social support from family, social networks, and peer groups. The availability of internal resources is governed by the level of psychological fitness, workload, psychological distress, and capacity for stress management. Reference Gotowiec and Cantor-Graae30,Reference Boswell35,Reference Hunt39 Allowing a space for ethics in pre-departure training and in the field, as well as in debriefing and long-term support after fieldwork, was therefore emphasized by both MSF and Schwartz, et al. Reference Biquet, Chang and Salvador31,Reference Schwartz, Hunt and Sinding43

Discussion

This study found that moral distress can be summarized as a stress reaction developed when the responder cannot follow inner moral values in various situations during a disaster response. However, in regard to more detailed accounts of moral distress, there are substantial differences in the literature. Furthermore, this study found that the difference between moral stress and moral distress is often vaguely explained.

In this study, three different types of moral distress were found and described within the disaster response. The first category, when the individual is hindered from doing what he/she perceives to be the right course of action in the situation, is characterized by external obstacles that prevent the responder from helping as intended. This includes being associated with or affected by others’ decisions or actions that one finds morally questionable, which leads to an increased sense of powerlessness. The second category, when the individual cannot live up to his/her own ideals, derives from situations where moral values are encroached irrespective of action taken. The third category, failing to do what is perceived as right even if possible, is related to the individual’s weakness of will (akrasia) to act upon moral values.

The first and the second types of moral distress are most commonly referred to in the literature. The study found that responders not able to decide their course of action themselves are more prone to moral distress. To observe misconduct while being unable to immediately act results in feelings of being morally complicit and may lead to a sense of personal failure and shame. Reference McCormack and Joseph46,Reference Buth, de Gryse and Healy47 Another type of moral distress, which has been mentioned by Jameton, is the reactive distress developed in the aftermath of the situation that involved moral challenges. Reference Jameton13 The authors in this study argue that reactive distress should be distinguished from other definitions of moral distress since the difference between Jameton’s description of the phenomenon of initial and reactive moral distress seems unclear.

Explanation of Moral Distress within Disaster Response

A conceptual model (Figure 2) was developed based on these findings to further map and display the linkage between the different concepts. To envisage the findings in this study, the conceptual model was developed also aiming at presenting the differences between moral stress, moral distress, and its potential consequences. This model is based on the theoretical mapping of the concepts; hence, it needs additional clarification in further studies regarding how risk and protective factors in reality affect responders. The model visualizes, in a timeline, the development of moral distress and the links between moral stress, moral distress, and its consequences. In this model, moral stress as a normative response to moral challenges is separated from moral distress and from other consequences. Depending on the intensity, duration, and frequency of moral challenges, moral stress may give rise to moral distress. It may be beneficial to also delineate moral distress from other negative consequences, which can be envisioned as secondary consequences to unmitigated moral distress. These consequences include those that concern moral aspects, such as moral residue and other more general negative psychological consequences, such as burnout. Finally, this study proposes that the long-term psychological outcomes form a feedback loop in that they influence the responders’ capacity to address future moral challenges through their influence on risk and protective factors. The risk and protective factors can potentially hamper and support development in each step.

Figure 2. Conceptual Model of Moral Distress.

This model displays a manifestation of moral distress with the interplay between the responder and the context. The overview of the different concepts in this model can facilitate future research and be used to illuminate how the concepts are inter-related. Further research is encouraged to explore the links between moral distress and psychological consequences. Moral numbness and detachment to moral aspects of care can be devastating consequences deriving from residues of moral distress, but also from work exhaustion, compassion fatigue, and burnout. Reference Epstein and Delgado48 The risk of developing psychological consequences has also been ascribed to an imbalance between inner beliefs and behaviour. Reference Thomas and McCullough15 At the time of this study, only one organization has put strategies in place to highlight these consequences: MSF has now emphasized their concern for moral distress, and pre-departure courses in ethics have been developed at a few operational centers. A motion has been put forward by the association of members in MSF urging ethics reflection, discussion, and concrete measures to reduce moral distress. In their motivation for these measures, improperly addressed moral challenges are described as leading to moral distress among fieldworkers, but also leading to job attrition, dysfunction in operations, reputational harm, and hardship for the beneficiaries. Reference Kiddell Monroe, Pringle and Calain49

What Explains Moral Distress?

The disaster response is defined by needs that are greater than the available resources, and so one can argue that responders would be both prepared for and familiar with these circumstances. Moral distress is, however, a stated problem, and perhaps responders from high-resource settings are more prone to moral distress? Holding regular employment in which there are plenty of resources could be a hampering factor for responders when they try to adapt to low-resource contexts. If the contrast between contexts is influencing the risk of moral distress, local staff who are used to working in low-resource settings should have lower levels of moral distress. However, the research on moral distress among local staff is limited. In one paper from 2014, Ulrich elaborated on moral distress experienced by African health workers due to the Ebola outbreak. Reference Ulrich50 In another study, moral distress was investigated among Ugandan nurses working in the HIV care. Reference Harrowing and Mill51 Indeed, the research unit (UREPH) in MSF urges comparative surveys on the prevalence of moral distress among fieldworkers and among locally hired staff. Reference Biquet, Chang and Salvador31

Engagement in disaster response and within humanitarian organizations is often branded with an urge to make a difference with a level of altruistic motivation. Reference Carbonnier52 This motivation can create a clash with reality when situational demands hinder the responders from acting on these motivations. Therefore, ambitious motivation could be a worsening factor regarding moral distress. In contrast, individuals who possess a sense of meaning through the work could be considered more resilient, more persistent, and constructive in their response to moral challenges. Nonetheless, it seems essential to aid responders and humanitarian workers to facilitate realistic motivations.

Morally challenging situations are ubiquitous in disaster settings, and it is therefore essential to highlight the impact of moral stress. There are several potential ways to interrupt the path from moral stress to moral distress and moral residue, such as proper training, individual preparedness, and support from the organization. Evidence of effective preventive measures and preparatory education is an area that has received little attention in the literature. Reference Schwartz, Hunt and Sinding43 Although individuals cannot be prepared for all the various moral challenges they will face, adequate knowledge of moral distress and its consequences might strengthen the moral courage and capacity to cope and seek support. Awareness of the circumstances that responders might face could promote more realistic motivations. Greater knowledge about the characteristics of moral distress, how to identify it, and how to provide support may be essential within organizations to create an environment where staff can seek support and openly discuss moral challenges.

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

The studies included in this review generally concern responders from high-resource settings. The findings may therefore have limited generalizability to local health care workers’ experiences of moral distress in low-resource settings. Furthermore, to clearly delimit the scope of this review, a decision was made to focus on moral distress; therefore, documents and handbooks focusing on staff well-being and psychological aspects of responders’ health without mentioning moral distress, moral stress, or ethical distress have not been included in this study. The results pertaining to how other psychological consequences link to morally challenging situations are therefore limited. Future studies may benefit from a broader scope to expand the understanding of these issues. In addition, although several concepts similar to moral distress exist in other contexts, these concepts were not included in the present review. Moral injury, which has been investigated among military veterans, Reference Litz, Stein and Delaney53 and stress of conscience are both similar to moral distress. However, these concepts were not included in the scope of this study. A possible avenue for future research would be to compare these concepts with moral distress. It is of note that publications produced in languages other than Swedish and English were not included. Although the extent of this literature is unclear, the focus on Swedish and English sources, mainly deriving from a western-oriented view of moral distress, may have contributed to the similarity of the definitions of moral distress mentioned in this review. Finally, although the authors’ own experience in humanitarian work has been the impetus for this review, individual experiences may result in preconceptions that influence the interpretation of the results. To mitigate this issue, the results were discussed extensively among the co-authors with no personal experience of working as disaster responders.

Conclusions

Several concepts exist that describe the outcomes of morally challenging situations, centering on situations when individuals are prevented from acting in accordance with their moral values. Their specific differences, however, suggest that to achieve greater clarity in future work, moral stress and moral distress should be distinguished. The authors in this study suggest that moral stress is a common reaction that includes feelings of frustration and powerlessness developed during morally challenging situations when individuals are prevented from acting in accordance with their values and ideals. In contrast, moral distress comprises the negative stress reaction that may develop in the aftermath if the responder cannot find constructive solutions or receive support. This study provides greater clarity in the different concepts of moral distress in the literature, which is essential to further examine how responders and humanitarian workers are affected by moral challenges.

Conflicts of interest

none

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X20000096