“For people to be successfully supported at home, a comprehensive assessment is an essential first step.” (Audit Commission, 2000: p. 43.)

Home visits by old age psychiatrists remain popular with elderly patients, their carers and general practitioners (GPs). Home assessments by various disciplines working with older people have been endorsed as a sign of good practice by the Audit Commission (2000) in their recent national report on mental health services for older people:

“Assessment at home is often better as people are most likely to behave and communicate in their normal way in familiar surroundings. Staff can also build a more accurate picture of people's needs and learn the views of their carers. Professionals can observe whether there is adequate food in the house, whether people can make themselves a hot drink, and whether there are any likely risks from poor hygiene or fire hazards.” (Audit Commission, 2000: p. 43.)

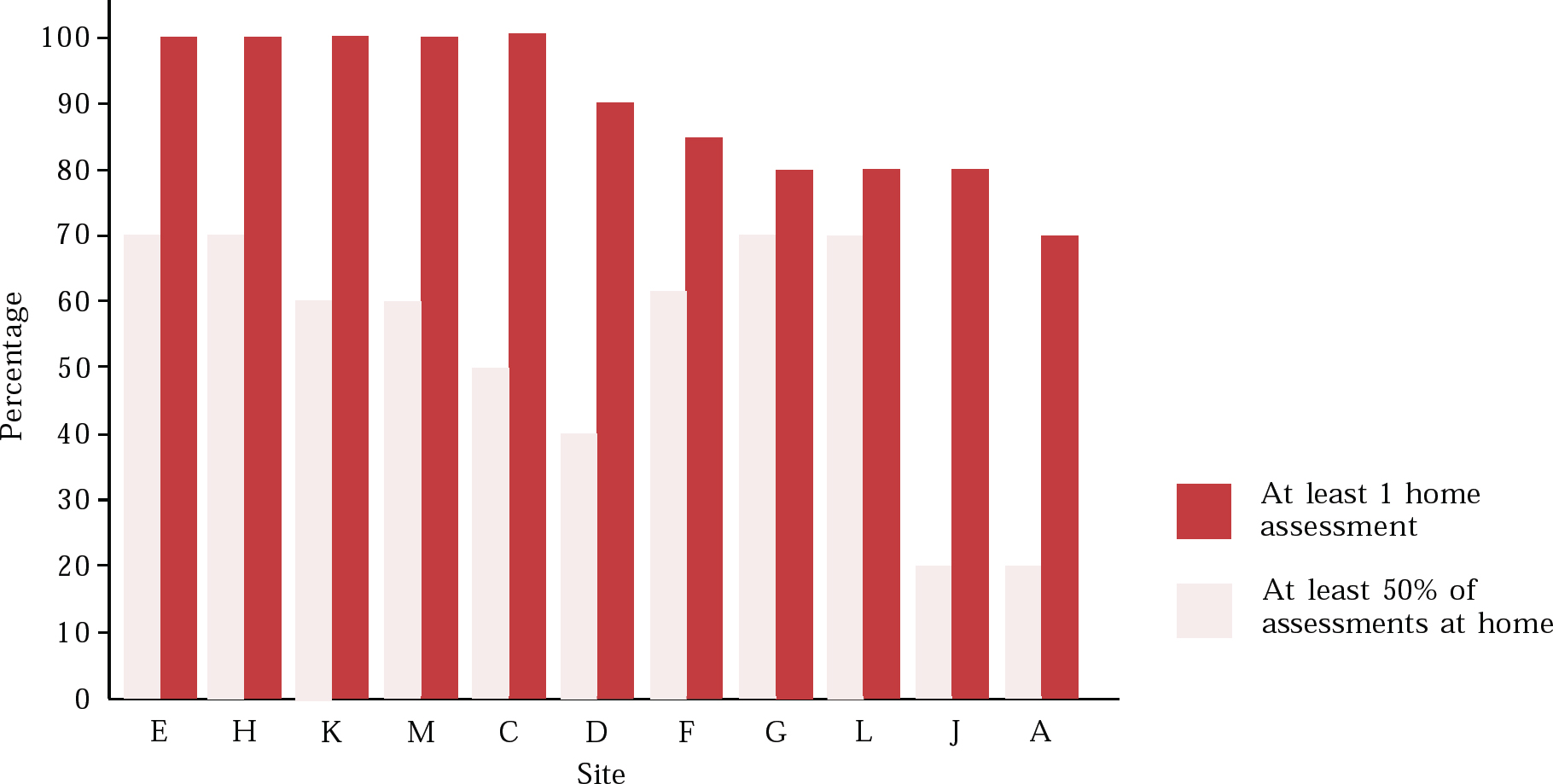

A first full assessment should lead to an overview of the whole situation and a diagnosis, if this has not been provided by previous contacts. It should also be the first stage of care management. The first assessment should lead to an approximate prognosis or expectation of developments in the future. It is good practice for most users to receive at least one home assessment by members of the community mental health team (CMHT). Figure 1 shows the percentage of users receiving home assessments found in a study of case files by the Audit Commission (2000).

The right of patients to be visited at home (a domiciliary visit) by specialists has been enshrined in the National Health Service (NHS) since it was created in 1948. Domiciliary visits are stated to be “at the request of the general practitioner, normally in his company, to advise on the diagnosis or treatment of a patient who on medical grounds cannot attend the hospital” (Department of Health and Social Security, 1981: p. 33). Compared with other NHS specialities, demands for home visits in the elderly have grown dramatically since the NHS was set up.

Despite the popularity and clinical importance of consultants' home visits, they are not part of the core NHS services, falling outside of the fixed sessions for a hospital specialist, and extra payment is incurred. This has contributed to a lively debate over the past few years about the function of consultant home assessment in the modern NHS, where multi-disciplinary working is the name of the game. One focus of this debate examines the equity of access to this service. In some regions, domiciliary old age psychiatry visits are made only by consultants and only at the request of the GP. In contrast, in other districts, home visits may be carried out by any CMHT member acting on a referral from almost any source, including a social worker, carer or concerned neighbour.

Standard 7 (mental health in older people) of the National Service Framework for Older People emphasises the need for services to:

“provide seamless packages of care and support for older people and their carers. The hallmark of good mental health services is that they are comprehensive, responsive, individualised, accountable and systematic” (Department of Health, 2001a ).

Home assessments are popular with patients, carers and professionals because assessment of the patient's socio-economic setting, carer issues and potential hazards in the home all contribute to a better understanding of problems and coping attributes. For example, looking in the fridge and the food cupboard provides a quick and informative check on food intake and the patients' ability to monitor when food is no longer safe to eat.

Ramsdell et al (1989) investigated the number of new problems revealed by home assessments of 154 patients by a geriatric nurse specialist, compared to an initial out-patient assessment of the same patients by a general physician. They found that the home visits identified one more problem in 111 (72%) patients and three or more problems in 35 (22.7%) patients above those identified in the out-patient assessments. Importantly, 23% of the new problems identified could have led to death or significant morbidity. Home review of patients' safety revealed problems in one in three patients. This study seems to provide much needed evidence to justify the increasing enthusiasm for home assessments.

To assess equity of access to this service, one would need a systematic collection of basic epidemiological data across the whole country. This has been a difficult task to carry out, not only because of the complexity of data collection, but also because there are so many variables that influence the provision and use of home services assessment (Box 1). A simple comparison of numbers can be very misleading. Dowie et al (1983) reported on national trends in domiciliary consultations and found that specialists in mental illness performed the second largest number of domiciliary visits after those in geriatric medicine. In the period 1949–1979 the figures collected by the statistical division of the Department of Health showed a general trend of increase in domiciliary visits across all specialities and visiting by consultant mental health care specialists at home has continued to increase, peaking in 1983. These figures are based on domiciliary visit ‘returns’ (forms documenting a visit) completed by consultants and forwarded to local health authorities by individual GP practices. As many home assessments are carried out by community psychiatric nurses (CPNs) and other members of the community team, the true demand and provision of this service is grossly underreported, as well as underresourced.

Box 1. Variables influencing the provision and use of home assessment

Availability of other methods of assessment

Provision of in-patient facilities

Demography of the local population

Estimates of local psychiatric morbidity

Measures of social deprivation

More detailed surveys of domiciliary visits in all NHS specialities were carried out in the Trent region by Coupland & Todd (1985). They found that 25% of the total number of visits were in psychiatry and 21% in geriatric medicine. They comment that the “general debility of old age necessitated the need for domiciliary consultations when attendance at out-patients' clinic was difficult” (p. 1401). In the Trent region, many patients were admitted directly as a result of the visit (32% in psychiatry and 64.7% in geriatric medicine).

The demand for domiciliary visits is related to the experience of the GPs and their willingness to manage patients at home as well as to the availability of consultant colleague guidance. The national NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2001b) proposes that GPs specialise, with a view to cross-GP referrals. How this proposal will change current referral practice is not clear. One aim of this development is to promote community assessment and treatment of dementia (which forms 80% of the clinical work of old age psychiatrists) (Liddell et al, 2001). Furthermore, dementia may become an even larger part of the work of specialists now that the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2001) has sanctioned the prescription of cholinesterase inhibitors for elderly people within the NHS only after specialist assessment by old age psychiatrists, neurologists or physicians specialising in care of the elderly.

Historical perspectives

Before the birth of the NHS, care was dependent on the financial means of the patient. Personal physicians would visit affluent patients at home, where care was delivered.

The introduction of Lloyd George's National Insurance Act in 1911 meant that workers were able to see their GPs free of charge, but their wives and families were not covered by the Act and had to pay. At this time, home visits often numbered 50 or more per day and were made on foot or bicycle. The demand on doctors' time was overwhelming and it is hard to imagine two busy practitioners attending together if attendance from a specialist was required.

However, specialisation was in its infancy and elderly people with chronic mental illnesses who also happened to be poor were accommodated in large municipal or voluntary hospitals, where bed numbers exceeded those allocated for the acute physical illness sector. These isolated mental hospitals accommodated up to 2000 patients.

Before 1946 there was also no expectation that mental hospitals would be part of the new NHS (Reference GeoffreyGeoffrey, 1998). The health and social infrastructure to cater for home assessment and management was not available for older patients with mental problems at that time, and despite the increase of NHS consultants, the responsibility continued to fall to the GP. Between 1961 and 1963 Annis Gillie chaired a general practice review, which saw the work of a GP as a coordinator of services and also highlighted GPs' educational needs – joint domiciliary assessment served this purpose. Until 20 years ago the assessment of an older person with mental health problems may have fallen to a geriatrician or a general psychiatrist, rather than an old age psychiatrist, although the speciality was increasingly establishing itself: it became a Section of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in 1978.

General practitioners and domiciliary visits

Initially, the domiciliary visit represented a collaborative style of working between the specialist and the GP. Analyses of how frequently GPs attended the consultation have been carried for all domiciliary visits and for old age psychiatry separately. For all specialities, joint visiting decreased from 28% (of 2711 visits) in 1967 (Reference Smith and BlytheSmith & Blythe, 1971) to 4% (of 338 visists) in 1984 (Reference LittlejohnsLittlejohns, 1986). Crome et al (2000) found that GPs were recorded as present in 1.2% (6 out of 486 visits) of domiciliary consultations in both psychiatry and medicine of old age. In a survey of the use of specialist old age psychiatry domiciliary visits by GPs in North Kent (Reference Hardy-Thompson, Orrell and BergmanHardy-Thompson et al, 1992) 27% (19) said they had attended at least one visit.

Difficulty with precise timing and the added difficulty of finding a compatible time for two busy doctors, usually at a short notice, have probably always been a factor compounding low GP attendance. This is evident even for section assessments, at which two doctors carry out a joint assessment. Encouraging GPs to attend for educational reasons may not be the most effective way of increasing their knowledge. Detailed correspondence from the consultant, a personal telephone call and continuing professional education focused on local needs may be more pertinent educational tools for GPs who already have core competencies and skills in the management of patients at home and also have had systematic rotational training.

There are varying reasons why GPs request a domiciliary visit. Sutherby et al (1992) and Crome et al (2000) examined the appropriateness of domiciliary visits as judged by other consultant psychiatrists (rather than other GPs) across the UK. These have revealed that agreement is not always possible.

Sutherby et al (1992) monitored domiciliary consultations for general adult psychiatry in Greenwich, London over a 6-month period. They concluded that the Terms of Service definition was fulfilled in 36 (30%) of the visits and agreed with the GPs that a further 45 (38%) cases needed an urgent assessment, but suggested that a CPN assessment or an urgent clinic appointment would suffice. Sutherby et al sought the opinion of specialists, but it would be equally revealing to obtain the views of fellow GPs on whether the definition of a domiciliary visit had been met.

It is inherent in the definition of a specialist that he or she will be able to manage more complex cases at home, have access to other resources and be generally more exposed to difficult patients, thus supporting the role of the GP. Other educational needs such as gaps in information about alternative local provisions can be identified through local audit and can be remedied with improved information made available to primary care providers. Crome et al (2000) audited requests for domiciliary visits in psychiatry and medicine of old age over a 3-month period, with peer review of selected visits by a consultant in the relevant speciality. They found that 74% (186/251) of the total number of visits were categorised as appropriate and 16% as inappropriate. When scrutinised according to speciality, all of the visits in old age psychiatry carried out at home were deemed necessary. In old age medicine 77% of the visits were thought to be appropriate; the majority of the disagreements by the physician peer reviewers was that the patient could have been admitted directly by the GP.

Studies show that GPs are very satisfied with specialist home assessments and find them a useful contribution to management. Analysis oyf GPs' views on specialist domiciliary referrals was carried out by Orrell et al (1992). Satisfaction was found to correlate with the GPs' use of this service and high users were found to have higher expectations of the service. The high users expected that a routine visit would be carried out within 24 hours, were influenced more by patients' physical disability when making a domiciliary visit referral and felt that domiciliary visits were a good way of assessing what other services were needed.

Assessments of social circumstances and collateral history inform future management and often need input from other non-medical disciplines. The need to match service provision to GPs' expectations is all part of good communication between the specialist and the GP. When 45 GPs were surveyed (Reference DowieDowie, 1981) using a semi-structured questionnaire asking under what circumstances they requested a domiciliary visit, they stressed the importance of assessing older patients at home. They felt that the most important reasons for requesting a domiciliary visit included assessment of home circumstances and how these influence the patients' mental health, and the presence of physical ill health or disability. A significant number also mentioned obtaining a consultant's opinion or facilitating an admission as being important.

With the development of primary care groups and trusts, GPs' views and needs will be increasingly important when developing a service. In their analysis of GPs' expectations of outcome following domiciliary visits, Orrell et al (1998) found a significant mismatch in expectation and service provision in the areas of CPN follow-up, out-patient appointment and admission. As primary care is involved more and more in the planning of services, GPs' expectations are likely to have increasing impact on future service development.

Srikumar et al (2000) carried out a follow-up of a cohort of older patients who had been assessed at home by a consultant psychiatrist 3 years earlier. They found that the CMHTs tended to follow up patients with depression, but that the care of patients with severe cognitive impairment and high dependency scores was more likely to be handed back to the GP. At 3 years, problems most likely to have improved included hallucinations and carer stress. Carer stress was seen to a lesser degree in those whose relatives were followed up by the CMHT than in those followed up by their GP.

Several authors (e.g. Reference Brown, Challis and von AbendorffBrown et al, 1996; Reference WattisWattis, 1980) have assessed the conditions most frequently considered for domiciliary assessment and analysed outcomes. Dementia and depression are the most common reasons for requesting domiciliary visits. Most of the patients seen are not in receipt of additional services and are cared for only by relatives. Significant numbers of carers of older patients suffer from carer stress, and a home assessment is very useful in identifying this. Carers and patients are generally very satisfied with the domiciliary service. Nevertheless, there are some problems with advocating assessments at home over those carried out in hospital. Practicalities such as professional time spent in travelling to and from individual assessments can have an impact on how many people are seen and could result in increased waiting times. Consultant-led ongoing reviews of patients in the community are associated with the same problems and cannot realistically be offered to patients on a routine basis without greatly increased provision of medical professionals. Hospitals provide a safer environment for taking blood-test samples and easy access to a pharmacy, and with the increasing use of diagnostic neuroimaging before antidementia treatment is started, comprehensive assessments can no longer be fully community-based.

Health care professionals are becoming targets of verbal and physical violence. Medical sites carry greater risk of assault (73%) than environments such as public transport (63%). Medical professionals working in accident and emergency departments, community settings and psychiatry are particularly at risk (Health Services Advisory Committee, 1987). Those carrying out home visiting are very vulnerable and their safety requires serious consideration and proper resourcing.

Coles et al (1991) studied a mental health service for older people that was hospital-based and included consultant-led home assessment, and analysed how its working changed when it was replaced by a new CMHT. They found that under the former system a consultant contracted for four sessions performed 109 domiciliary visits. Under the new system, a CMHT of six full-time non-consultant professionals with senior medical support assessed 193 patients. The CMHT was able to work with both patients and their relatives over a longer period of time, thus meeting a previously unmet need not only in clinical management but also in numbers of patients seen. However, 44% of the patients seen by the team were also seen by a psychiatrist. As the pharmacological treatment of dementias becomes more widespread, this number can be expected to rise. There were no statistical differences in the numbers of patients admitted following either the consultant or team assessment. Thus, consultant old age psychiatrists, with their breadth of medical and psychiatric experience, skill in working with colleagues from other non-medical disciplines and ability to bridge community and hospital provision, remain well placed as leaders and developers of service provision. This is recognised in the NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2001b), which provides for over 200 new consultant posts.

Multi-disciplinary teams and domiciliary visits

Initial home visits may be arranged in a number of ways, depending on the design of the local service. Many CMHTs accept initial referrals directly, with non-medical practitioners carrying out initial assessments.

A recent Audit Commission report (2000) found that community referrals (from non-medical practioners) could make services more responsive to need, but that they were not common. Self-referral or referral by carers were possible in only two of the Commission's 12 study sites. Table 1 shows the composition of the CMHTs at 11 of these sites. In some services, the CMHT model had evolved to such an extent that all of the care in the community was home-oriented and day hospitals did not feature in service provision. For any mental health team to qualify as a CMHT it must include at least two professions and meet at least weekly to discuss current cases and referrals. However, consultant psychiatrists described themselves as members of CMHTs in only six of the 12 sites. Only half the teams included social workers and/or occupational therapists and two had CPNs only.

The rise of the CMHT model has led to concerns about diagnostic accuracy and acceptability to referring GPs, as well as about indemnity issues and professional boundaries that members may not be willing to cross. Collinghan et al (1993) carried out a study evaluating the accuracy of psychiatric diagnosis by two multi-disciplinary teams in London that had been established for 9 and 6 years prior to the study. The team members used a semi-structured schedule, which was then presented at weekly team meetings. The authors found that the team diagnosis reached a 90% concordance with the diagnosis of a research psychiatrist; dementia was the diagnosis with the highest misclassification rate. The authors noted that the teams were mature and experienced and that the same findings might not apply to less developed teams. The consultant psychiatrist's time was used only for difficult or urgent cases, which freed them for supervisory and managerial roles. This way of working may suit team members who are particularly keen to develop their clinical and professional skills.

A criticism of the CMHT approach is that less of the consultants' time is spent on direct patient contact (Reference Helme, Besson and FottrellHelme et al, 1993; Reference JolleyJolley, 1993). Spreading doctors' time thinly could reflect the continuing shortage of consultant time in old age psychiatry, with catchment areas that are too large, a low level of service provision and too many patients for the doctor to be able to see each one referred.

To help retain senior CPNs in clinical practice there is a governmental initiative funding senior practitioner and consultant nursing grades (although the precise number and their role in continuing to deliver service remains to be seen). However, not all members of a multi-disciplinary team may feel happy to take on an extended role, although they may be happy to deliver service to patients in the community according to their existing professional capacity.

Conclusions

There is good evidence that home assessments are effective and are popular with patients, carers and staff. They are part of mental health practice and should be developed further to help patients remain at home and to support GPs. The original definition of a domiciliary visit would benefit from modernisation to reflect the reality of service provision. It is also important not to underestimate the needs of the multi-disciplinary team in terms of training and supervision, clinical development and support, with the consultant taking a lead in this. Part of the role of the consultant is to provide ‘hands-on’ clinical leadership and this should include carrying out home visits. Although domiciliary assessments are desirable, some patients do not want professionals to visit their home and others may be better seen as out-patients – sometimes home assessments have less to contribute to the overall assessment. Further research should look at both cost-effectiveness and the best ways of developing multi-disciplinary working. Good practice for home assessment is summarised in Box 2.

Box 2. Good practice for home assessments

Accept referrals from any source, but encourage central involvement of GPs in referral process

Have a single point of access for referrals to CMHTs for home assessments

Involve an experienced psychiatrist in the triage process for new community referrals

Ensure that a consultant psychiatrist maintains a key role in home assessments

Encourage multi-disciplinary involvement in home assessments

Ensure systematic training and support for all CMHT members carrying out home assessments

Use a standardised assessment form, to allow systematic evaluation of the patient (e.g. the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE; Reference Reynolds, Thornicroft and AbasReynolds et al, 2000))

Ensure that a detailed inspection of the social environment is conducted as an integral part of the assessment

Multiple choice questions

-

1. As regards home assessments:

-

a the Audit Commission has endorsed them as a sign of good practice

-

b their provision is accurately reflected by consultant domiciliary visit returns collected by local health authorities

-

c their provision is affected by many other service provision variables

-

d the multi-disciplinary way of working is well defined

-

e development of the domiciliary assessment service must consider adequate increase in staffing.

-

-

2. As regards GPs and home visits:

-

a joint consultation by consultants and GPs occurs in at least 50% of visits

-

b the Terms of Service definition is fulfilled in about 30% of cases

-

c an audit of GP requests for home assessment showed that all were judged appropriate

-

d the Audit Commission recommends that old age services accept referrals from agencies other than GPs

-

e joint consultant and GP home assessments play a key role in GP postgraduate education.

-

-

3. As regards home assessments and diagnoses:

-

a well-established CMHTs achieve good diagnostic accuracy

-

b requests for old age psychiatry consultant home assessments are most frequent for patients who have dementia

-

c assessment of older people at home can reveal more serious problems than clinic assessment

-

d at follow-up, a higher proportion of those with affective disorders remain in their own homes compared with those with organic disorders

-

e GPs with access to specialist advice on dementia and depression are significantly more likely to value early diagnosis for dementia.

-

-

4. As regards home assessments and outcomes:

-

a consultants in large catchment areas see fewer patients at home than those in smaller catchment areas

-

b home visits identify and reduce carer burden more effectively than clinic-based assessment

-

c the clinical settings most frequently associated with violence are community settings and psychiatry

-

d people seen on home visits frequently have a concomitant physical disease

-

e about 20% of patients seen on a domiciliary visit are admitted.

-

-

5. As regards home assessments by the GP:

-

a the majority of GPs always expect an admission

-

b joint domiciliary visiting by GPs and psychiatrists has become less common

-

c the majority of GPs expect home visits to help in obtaining other services

-

d the majority of GPs would have seen the patient within the previous 3 days

-

e assessment of the home environment is the most frequent reason for home visits.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | F | a | T | a | T | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | T | b | T | b | T |

| c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | F |

| d | T | d | T | d | T | d | T | d | T |

| e | T | e | T | e | T | e | T | e | T |

Table 1 Membership of community mental health teams (CMHTs) at 11 of the 12 sites studied by the AuditCommission (2000)

| Study site | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membership of CMHT | A | C | D | E | F | G | H | J | K | L | M |

| Consultants | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Community psychiatric nurses | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social workers | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Psychologists | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Occupational therapists | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Physiotherapists | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

Fig. 1 Percentage of users receiving home assessments, as identified from patient care files in representative areas of England and Wales selected by the Audit Commission (2000, with permission)

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.