Chronic meningitis is defined as meningeal inflammation of the subarachnoid space associated with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis persisting at least 4 weeks. Reference Hildebrand and Aoun1 It is a major diagnostic challenge for clinicians since symptoms are often nonspecific and the differential diagnosis is wide, including infectious, autoimmune/inflammatory, and neoplastic disorders. Reference Thakur and Wilson2 Yet an accurate diagnosis is necessary in order to provide targeted treatment and is a key determinant of morbidity and mortality. Here, we present two cases of previously healthy patients who presented with granulomatous meningitis on brain biopsy. Clinical, radiological, and histopathological evidences are discussed.

A 25-year old man from Kosovo presented with fluctuating fever and persistent weight loss (13 kg) over 1 year, associated with headache and cerebellar symptoms (Case 1). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) disclosed diffuse nodular leptomeningeal enhancement (Figure 1A–B). CSF analysis showed lymphocytic-predominant leucocytosis, increased protein level and low glucose index (Table 1). Routine blood work-up was normal, and large infectious work-up (Annexe), autoimmune and (para-) neoplastic screening (thoracic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) (Figure 2A), and screening for paraneoplastic antibodies in blood and CSF) were negative. Meningeal biopsy showed confluent granulomatous lesions with central caseous-like necrosis (Figure 3A–B). Although the enzyme-linked immunospot (Elispot) assay, as well as several CSF and brain biopsy polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cultures were negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), a tuberculous meningitis was suspected in this patient from a high incidence country and a therapy of rifampicin, ethambutol, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide was initiated, together with a tapering oral prednisone course.

Figure 1: Brain MRI of Case 1. Initial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted brain MRI on axial plane demonstrated diffuse nodular leptomeningeal enhancement in the sulci (A, thick arrows) and choroid plexus (thin arrows), in the basal cisterns (B) around the optical chiasm and rectus gyrus (arrowheads), and around the mesencephalon (dashed arrows), as well as in the internal auditory canal and along the spinal cord (not shown). Three-month follow-up MRI after antituberculous treatment initiation showed increase in leptomeningeal thickening (C and D). After anti-TNFa introduction, MRI demonstrated complete resolution of nodular leptomeningeal enhancement (E and F).

Table 1: Basic characteristics of first cerebrospinal fluid analysis for both cases

* On second CSF analysis.

Figure 2: Initial and follow-up computed tomography of Case 1. Initial thoracic contrast-enhanced computed tomography on axial plane (A) did not show any mediastinal lymph node. Follow-up imaging was performed after initiating therapy. It revealed multiple enlarged mediastinal and peribroncheal lymph nodes (arrows, B and C) but no parenchymal abnormality (D).

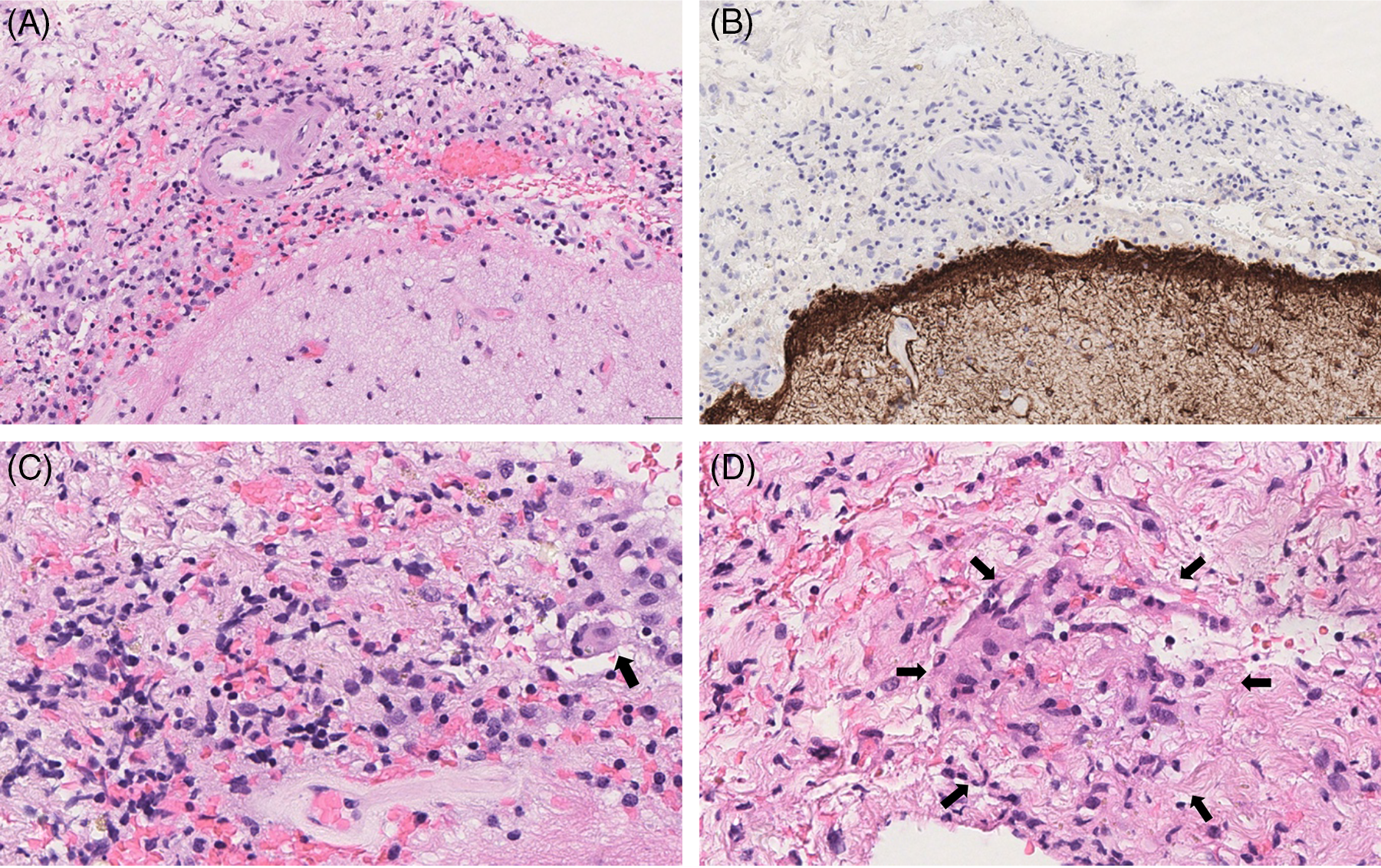

Figure 3: Histopathology for Case 1. Left frontal lobe brain biopsy: brain parenchyma and meninges were extensively infiltrated by irregular confluent granulomatous lesions (HE, initial magnification x2.5) (A); granulomas were of various age composed of epithelioid cells, rare giant multinucleated cells, and frequently centered by caseous-like necrosis very suggestive of tuberculosis even in the absence of mycobacteria on Ziehl–Neelsen coloration (HE, initial magnification x20) (B). Mediastinal lymph node biopsy: lymph node parenchyma was extensively infiltrated by rather regular granulomatous lesions (HE, initial magnification x2.5) (C); granulomas were round, well defined, mostly composed of epithelioid and, without any focus of necrosis and, suggestive of sarcoidosis (HE, initial magnification x20) (D).

Three months after antituberculous treatment initiation, the patient kept worsening, with new psychiatric and cognitive symptoms, generalized seizures, persistent CSF alterations, and worsening of meningeal enhancement on brain MRI (Figure 1C–D). A course of corticosteroids as add-on therapy to the antituberculous treatment was followed by clinical improvement, leading to the hypothesis of a dysregulated immune response to M. tuberculosis. After consulting both infectious diseases’ experts and immunologists, anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa) was introduced in parallel to the antituberculous therapy. A complete resolution of leptomeningeal enhancement was observed (Figure 1E–F) and the patient fully recovered with a normalized neurocognitive evaluation and no seizure recurrence. Nevertheless, on every attempt to stop infliximab, the patient relapsed. After the first relapse, while still on antituberculous treatment, thoracic CT scan was repeated and this time revealed mediastinal and hilar lymph node enlargements (Figure 2B–D). Histological evaluation of the lymph nodes showed multiple rather well-defined epithelioid granulomas without any focus of necrosis and histologically favoring sarcoidosis lesions (Figure 3C–D). The patient was diagnosed with a multisystem sarcoidosis and azathioprine was added to infliximab therapy. At 3 years, the patient had fully recovered with no further relapses.

A 79-year-old Swiss woman, without relevant medical history, developed over 2 weeks somnolence, confusion, and persistent fever, following an adequately treated Escherichia coli bacteraemia of urinary tract origin (Case 2). Brain MRI demonstrated generalized leptomeningeal enhancement on T1-weighted gadolinium-injected sequences and ventriculitis (Figure 4A–C), and CSF analyses showed lymphocytic pleocytosis with increased protein and low glucose index (Table 1). Given the high suspicion of infectious meningitis, an empiric antibiotic and antiviral therapy was initiated. Extensive infectious (Annexe), autoimmune, and (para-) neoplastic work-up came back negative and the patient kept worsening. Brain biopsy showed a diffuse meningeal granulomatous infiltrate with numerous epithelioid histiocytes and rare giant cells without clearly organized granulomas nor evidence of M. tuberculosis (Figure 5A–D). Tuberculous meningitis and neurosarcoidosis were both considered in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous diseases, although the infectious work-up and positron emission tomography (PET)-CT were negative (Figure 6A–C). A dual approach was decided with antituberculous treatment along with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone, followed by a gradual prednisone tapering. The patient became afebrile and showed neurological improvement within a week of treatment, followed by gradual worsening after involuntary interruption of the antituberculous therapy (after 14 days of treatment). Antituberculous treatment was then adapted and the patient further improved over a period of 6 months. MRI showed a resolution of inflammation with a remaining slight ventricular enhancement (Figure 4D–F). At last follow-up (12 months after treatment discontinuation), she still had cognitive issues and difficulties to walk without aid but kept improving and had not experienced any relapses.

Figure 4: Brain MRI of Case 2. Initial brain MRI (top row) using axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging demonstrated hyperintense filling of the left post-central sulci (A, arrow), also known as the “Ivy sign,” with only faint enhancement on axial T1-weighted after i.v. contrast injection (B, dashed arrow) associated with right ventriculitis (C, thick arrow). Posttreatment MRI (bottom row) demonstrated normalization of the subarachnoid space (D), disappearance of sulcus enhancement (E), and only faint ventricular residual enhancement (F).

Figure 5: Histopathology of Case 2. Left frontal lobe brain biopsy: meninges were thickened and infiltrated by inflammatory cells (HE, initial magnification x10) (A); reactive astrogliosis without inflammatory infiltrate was observed in brain parenchyma (GFAP immunohistochemistry, ABC-peroxidase/DAB, initial magnification x10) (B); in the meninges, inflammatory infiltrate was composed of lymphocytes, rarest plasma cells, and numerous histiocytes with epithelioid feature and rare multinucleated cells (arrowed), (HE, initial magnification x40) (C); focally, histiocytic epithelioid cells exhibited a vague granulomatous arrangement without any focus of necrosis (HE, initial magnification x40) (D).

Figure 6: Initial PET-CT of Case 2. 18F-FDG PET-CT did not show any abnormal uptake focus either on maximum intensity projected view (A) or on axial fused images (B). There was also no parenchymal abnormality on the CT lung windows (C).

The two aforementioned cases illustrate the difficulties and frustration when dealing with isolated chronic meningitis cases, known to be a diagnostic challenge, not only because of the variety of clinical manifestations and causative factors (viral, bacterial, or fungal infections, autoimmune diseases, granulomatous disorders, carcinomatous meningitis, and paraneoplastic disorders among others) but mostly, because of the limited sensitivity of the available ancillary tests to yield a definitive diagnosis. Reference Baldwin and Avila3

In our first case, multiple elements were suggestive, although not specific, of neurotuberculosis: the patient origin from a high incidence country, Reference Kurhasani, Hafizi, Toci and Burazeri4 the diffuse leptomeningeal gadolinium enhancement with brain stem and cranial nerve predominance, Reference Wang, Luo, Zhang, Liu, Liu and He5 the lymphocytic pleocytosis of a few hundred cells/μl with elevated protein, elevated lactate with a typically very low, sometimes undetectable CSF glucose, and the presence of caseating granulomas on meningeal biopsy Reference Rock, Olin, Baker, Molitor and Peterson6,Reference Schaller, Wicke, Foerch and Weidauer7 (Table 2). Caseating granulomas with central necrosis are typical of tuberculosis (present in up to 80% of suspected cases Reference Gupta, Lobo, Adiga and Gupta8 ), although they can rarely be observed in other granulomatous diseases, including sarcoidosis. Reference Aubry9,Reference Noiles, Belenzay, Crawford and Au10 Interestingly, the infectious work-up was completely negative for the presence of M. tuberculosis, in blood, CSF, and brain tissue, both by culture and PCR detection. Given the low and variable yield of these exams (sensitivity of antibody and antigen assays for M. tuberculosis varies from 38 to 94%, Reference Rock, Olin, Baker, Molitor and Peterson6 cultures are positive in 23%, acid-fast bacilli smears in 20%–90%, Reference Thwaites, Chau and Farrar11 and PCR in 18%–100% Reference Rock, Olin, Baker, Molitor and Peterson6 ), the absence of alternative diagnosis and the high suspicion for tuberculous meningitis the patient was treated with quadritherapy (rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) and adjunctive low-dose corticosteroids, this approach being reported as able to improve survival. Reference Prasad, Singh and Ryan12

Table 2: Common clinical features and CSF findings during neurological involvement in tuberculosis and sarcoidosis patients

* ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme.

† ADA: adenosine deaminase.

Nonetheless, the clinical course with relapses at steroid tapering with improvement under pulse courses of methylprednisolone was unexpected for this diagnosis. While progressive deterioration is expected in untreated neurotuberculosis with high morbidity and mortality, evolution is characterized by gradual improvement under treatment. In our case, we considered that the absence of improvement after 3 months, despite a well-conducted antituberculous treatment, reflected an immune-mediated exacerbation triggered by tuberculosis treatment. Thus, in an attempt to control this alleged paradoxical reaction, we decided to add an anti-TNFa agent in order to tame the M. tuberculosis-specific exaggerated cellular immune response as it has been previously described. Reference Blackmore, Manning, Taylor and Wallis13 The use of anti-TNFa in a tuberculosis is not common practice and should not be considered without multidisciplinary evaluation by infectious diseases’ experts, neurologists, and immunologists, as was the case in our hospital. The spectacular improvement following anti-TNFa and subsequent relapses at its discontinuation questioned the initial diagnosis and led to a new series of ancillary tests and a final diagnosis of sarcoidosis, almost 6 months after the onset. Retrospectively, the patient had severe neurosarcoidosis, corticosteroid-resistant, which was spectacularly improved by anti-TNFa.

We consider this first case to be didactic for two reasons: (1) careful and constant reassessment for evidence of the underlying pathology is valuable in the follow-up of chronic patients notably in the absence of bacteriological proof. In patients with isolated chronic meningitis, we suggest a complete diagnostic work-up at presentation, and, depending on the patient evolution, a thorough follow-up at 3–6 and 12 months with a brain MRI with gadolinium and a contrast-enhanced chest CT scan (or PET-CT if possible); and (2) adopting a dual-therapy approach (antituberculous treatment with steroid tapering) may be suggested when definitive diagnosis is not possible and extensive infectious work up is negative. Deterioration after 3 months of well-conducted antituberculous treatment, or during/after steroid tapering should prompt the realization of new extensive work-up (see point 1). In case of persistent doubt, use of immunosuppressive agent, adjuvant to the antituberculous treatment, should be the subject of a multidisciplinary evaluation.

The second case underlines other issues in case of chronic meningitis patients. Despite the absence of exposition or risk factor (such as prior immunosuppression or country at risk), the CSF pattern as well as the presence of ventriculitis in the MRI were suggestive of an infectious cause. Exhaustive work-up (including PET-CT) was negative and brain biopsy showed a nonspecific granulomatous inflammation without organized caseating or non-caseating granulomas. A high level of adenosine deaminase (ADA) in the CSF, which is a T-lymphocyte-produced enzyme, speaks in favors of a granulomatous meningitis of tuberculosis or sarcoidosis origin rather than of meningitis of other causes. Nevertheless, with a sensitivity of <59% and specificity of >96%, a normal value cannot rule out a granulomatous origin. Reference Tuon, Higashino and Lopes14 Complementary to ADA, recent publications suggest that high levels of serum soluble IL-2R have a high specificity (85%) for sarcoidosis over other granulomatous or infectious diseases. Reference Eurelings, Miedema and Dalm15 On the other hand, CSF-soluble IL-2R does not discriminate between neurosarcoidosis and neuro-tuberculosis, although it could be a valuable tool to assess the response to treatment. Reference Petereit, Reske and Tumani16

Although the prevalence of the sarcoidosis in Switzerland, in an immunocompetent patient, is higher than tuberculosis, negative PET-CT scan, alveolar lavage with normal CD4/CD8 count in bronchoscopy, and aspecific brain biopsy findings did not allow the diagnosis to be retained. Following initiation of empiric antituberculous therapy, the patient improved. Given the absence of definitive diagnosis, the patient underwent continuous assessments (repetition of lumbar punctures and brain MRIs, active research of primary neoplasm, and other causes of granulomatous meningitis). In parallel, the patient gradually worsened following an involuntary interruption of the antituberculous treatment while still on steroids and improved significantly after dose readjustement. She continued to improve after tapering of steroids leading eventually to the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis.

In conclusion, suspecting tuberculous meningitis is reasonable in patients with cryptogenic chronic meningitis, in whom common mimics are excluded and exhaustive infectious work-up has been performed. The incidence of tuberculosis varies between European countries and through time, making it difficult to estimate the probability of this infection. Thus, we suggest not to withhold from empirical therapy when initial work-up is inconclusive, given the high morbidity in neurotuberculosis patients. Furthermore, increased awareness and careful re-assessment of the treatment plan are essential and should be evaluated regularly.

Acknowledgments

We thank our collegues in the departments of Neurology, Immunology and Infectious Diseases (University Hospital of Lausanne) for useful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

VP received funding for travel from Biogen Idec and Merck, none related to this work. CP and MT served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi-Genzyme and received funding for travel or speaker honoraria from Biogen Idec, Merck, Roche, and Sanofi-Genzyme, none related to this work. RDP served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Celegene, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi-Genzyme and received funding for travel or speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Biogen Idec, Celegene, Merck, Roche, and Sanofi-Genzyme, none related to this work. AS, FD, MJ, AA, AK, VD, and JPB did not have any support from commercial sectors, related or unrelated to this work.

Statement of Authorship

AS, FD, and VP wrote the manuscript. AS, FD, AK, MJ, VP, AA, and RDP were involved in the patient’s care at the University Hospital of Lausanne. MJ, AA, AK, MT, CP, RDP, and VP reviewed the manuscript. VD prepared and reviewed all MRI images and reports. JPB prepared and reviewed all pathologic images and reports. All authors were involved in the editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2021.138.