In the generation before the Civil War, white Southerners of both genders had a wealth of useful knowledge about the places where they lived. They knew the landscape, the geography, the complicated social relations among its people, and the nuances of local history. In addition, many residents had a set of highly developed skills which were necessary for the functioning of individual households and entire communities. These skills provided human beings with status among their peers, as well as personal satisfaction in the exercise of their talents. In their daily lives, Southerners relied on each other for companionship, fellowship, and assistance in times of trouble. They had their share of conflicts based on class and other issues, but most people from different social backgrounds fostered an ethic of communalism, the notion that they had obligations to one another.1

In the antebellum years, white Southerners also lived in a world of abundant material resources. They knew how to manage these resources – food, timber, and habitat – each of them valuable in a distinctive way, each of them necessary for human survival. This was true throughout the South, despite subregional differences in diet, landscape, and architecture. Most white people valued their material resources, using them for their own well-being and the benefit of their relatives, friends, and neighbors, whether they were planters, yeomen, attorneys, doctors, editors, ministers, or craftsmen in the rural and small-town South. They were willing to share their resources with each other, too, in the spirit of both obligation and cooperation. This universe of “rude plenty” seemed to provide enough for everybody, according to Letitita Dabney Miller, a judge’s daughter. Some white people wasted, abandoned, or misused resources, although most of them practiced stewardship, trying to avoid the needless destruction of resources whenever possible.2

People

We should begin with the people themselves. Most white Southerners shared an interlocking set of values on family duty, gender, religious faith, and honor, all of which could be subsumed under the rubric of communalism. The foundation of communalism was the family, the central institution in the lives of most people. Kinfolk mattered well beyond the nuclear core of parents and children, embracing a wide network of relatives. Many people knew the detailed histories of their families back to their great-grandparents and beyond, and many of them lived surrounded by their kin. Within the boundaries of Anderson County, South Carolina, Micajah A. Clark had relatives in sixteen households, embracing cousins, aunts, and uncles with seven different surnames. Multiple generations sometimes lived in the same household, for months or even years at a time.3

Kinfolk, male and female, were expected to help each other in daily life, a concept they absorbed early in life. They practiced the idea as adults, creating a dense web of favors and obligations. James Deaderick, an attorney in Tennessee, borrowed money from a cousin to purchase land, and he knew he could rely on the man’s generosity. Kentuckian Sarah Thompson, a plantation mistress, asked her kinfolk about household tasks such as how to weave a carpet properly and how much cloth was required. Relatives male and female congregated at the local church to worship together and visit after the service, and they attended court day once a month at the county seat to hear the news, do business, and talk some more. They readily gave lodging to kindred passing through the area. Plantation mistress Ann Archer sheltered her cousin’s son as he traveled through Mississippi, even though he drank too much and was “very disagreeable to us.”4

Friends and neighbors engaged in similar habits of mutuality, creating another layer of obligation between community members. White people swapped many favors large and small in their daily lives. In Walnut Hill, South Carolina, one Mrs. Pledger visited her neighbors, the McLeods, to ask them to write some letters for her. Young Kate McLeod did not especially enjoy writing these “rigamaroles” for her elderly neighbor, but she did it, as expected. When some drunken white men serenaded the Carney household in Tennessee before the local elections in 1859, one of the songsters dozed off on the porch, so Mr. Carney, a merchant, asked him to come into the house and sleep it off. Neighbors sometimes collected mail for each other at the county seat and distributed it to the different households. Being a good neighbor was something that other people in this social world noticed and remembered.5

Hospitality was a time-honored, highly effective way to forge these social bonds. Relatives, friends, and neighbors visited each other’s houses regularly, sometimes on the spur of the moment, while other visits, lasting several days or longer, were planned in advance. Southerners enjoyed formal social gatherings, as well. Every comfortable home had a room for receptions and parties, Texan Mary Maverick recalled, and the celebrations increased at the holidays, when people gathered to talk, listen to music, and eat. During the rest of the year, many whites felt obliged to give shelter to white people passing through. John Franklin Smith’s father, who owned a plantation in Bates County, Missouri, never turned travelers away and gave them free lodging in his house. Not everyone measured up to such generosity, but that was the ideal.6

The communalism of the Old South included white Yankees who moved into the region, as well as European immigrants, so long as they accepted the institution of slavery. Jason Niles, a Vermont native, moved to Mississippi in the 1840s to practice law, and by 1861 he had a thriving legal practice in Attala County, where he was a respected neighbor with many friends. The same process happened with the region’s population of European immigrants. Germans and Irishmen settled in towns such as Staunton, Virginia, not just in the big cities, and, despite some bursts of nativism and anti-Catholic prejudice – since many of these newcomers were Catholics – they lived for the most part peacefully with their Anglo-Saxon Protestant neighbors. The same was the case for the small numbers of Jews who settled in the South’s towns and villages.7

Class relations between whites in this society was a delicate matter. Slaveowners, who held most of the property, had to ensure the loyalty or at least the acquiescence of other whites. Many of them tried to keep these relations in good repair, out of enlightened self-interest, religious obligation, and what seems like a genuine desire to help other people. In Manchester, Virginia, Rebecca Harris was much sought after by her neighbors for her nursing skills. White people of every background asked her to care for them, and she usually responded. In low-country South Carolina, plantation owners realized that yeomen farmers needed money when they would offer to sell baskets or yarn to their affluent neighbors. One planter’s daughter said that parties on both sides understood these wordless transactions. Family connections to prominent people could mediate the snobbery of elite whites. Anne Broome, an ex-slave living near Winnsboro, South Carolina, noted that local planters were “good” to a working-class white man named Marshall because he was related to the Chief Justice of the United States, John Marshall.8

Gender influenced how white Southerners learned to manage certain material resources. Beginning in childhood, they absorbed the idea that the sexes had to play distinct roles in the world. Boys learned how to hunt, fish, ride, and handle a gun, while girls learned how to cook, sew, and run a household. In adult life, this clear differentiation continued in the use of material resources, as was true for many cultures. The sexes had diverging areas of expertise, although both men and women had knowledge that was necessary to keep households running. Men made most of the important decisions in the family, and women were expected to resign themselves to their subordination; in return they would be protected. Women who could not accept these strictures, such as the South Carolinians Sarah and Angelina Grimké, left the region for the North, where they embarked on careers as reformers.9

Southern communities were brimming with all kinds of personal information, acquired by the residents over years of observation. Most white people cared a great deal about the good opinion of their neighbors, and both sexes could communicate their disapproval with sharp talk. Hardy Wooten, a doctor, called the young men who collected in the grog-shop in Lowndesboro, Alabama, drinking and talking, “gossips in the strongest sense of the term.” Women queried each other about rumors of misconduct, and the consequences could be serious. Texan Elizabeth Clary and her sister speculated that a neighbor in Grimes County had committed adultery, and, when that item of gossip spread through the community, the local Methodist church opened an investigation into the matter. Women and men did not want to be subjected to social disapproval. Ann Gale, a plantation mistress, advised her son not to repeat her candid opinions about some difficult relatives because she had “a dread of being talked about” herself.10

When a disaster occurred, such as a fire, white Southerners expected everyone to help out. Many communities had volunteer fire departments, but when a fire broke out, everyone, adults and children, rushed to the scene. Neighbors sometimes called for assistance by sounding a horn. After a carpenter’s shop went up in flames in Alexandria, Virginia, firemen and local citizens worked together to prevent the fire from spreading. The Great Dismal Swamp, which covered over 100,000 acres on the Virginia–North Carolina border, sometimes caught fire, and the conflagration spread into both states, consuming homes, trees, and fences as citizens tried to fight the flames. They had a justifiable fear of fire, which often started with a lightning strike and could spread rapidly in the countryside.11

For good or for ill, local institutions shaped the existence of most whites in the rural and small-town South. The national government had a negligible presence in their lives. The postmaster was probably the most visible federal employee, and, even then, local people sometimes took over that function and delivered mail to their neighbors. The federal census-taker, who came around once every decade, was a local resident, as warranted by law. The court system, staffed by magistrates almost everyone knew, met in taverns, mills, and private dwellings, and they resolved the cases – disorderly conduct, drunkenness, theft, assault, and murder – that caused shame and heartbreak in the community.12

Ordinary breaches in communalism happened, of course, in every county, village, and town. Every community saw its share of rivalry, pettiness, and meanness, as white people criticized, reproached, or snubbed their contemporaries. Class tensions could never be completely suppressed, breaking the surface of daily life. In Mississippi, yeomen were known to insult white women riding in fancy carriages and white men who wore fine clothes. Not all members of the planter class tried to conceal their disdain for working-class people. Robert Williams, a former slave, said that his master Clinton Clay made poor whites go to the back door if they wanted to speak to him. The worst penalties were inflicted on those who breached customs about race. In North Carolina, planters who caught working-class whites bartering with slaves “banded together” to force them to sell their farms and leave the area, threatening them with death if they did not comply. Renegades such as Sarah Grimké, Angelina Grimké, William H. Brisbane, and James G. Birney who openly criticized slavery chose to leave the region or were forced to leave.13

Sustenance

White Southerners expressed their communalism in tangible ways, among them the consumption of food. The region was an agrarian wonder, replete with fertile farms and plantations where cattle and hogs grazed in the fields, poultry pecked in the yards, fish teemed in the rivers, and wild game roamed in the woods. Most planters ate a better diet than middling slaveowners, who in turn ate better than most yeoman farmers, but the region had enough provisions for most of its people. Many Southerners consumed a diet that was high in protein, salt, and sugar, and most of them perceived food as an essential resource that should not be wasted. Willis Lea, a physician who lived in a log cabin, proudly told his brother that he lived well, he ate well, and his family was healthy. Having a healthy appetite and plentiful food were important components of the good life, Alabaman Matilda Finley remarked.14

Women were responsible for most of the food preparation, which has been true for many societies. In the Old South, this was the case for white women of all social classes, from yeomen farmer’s wives to plantation mistresses. Eliza Robertson of Louisiana, a planter’s wife, could make head cheese, mincemeat, citron preserves, and sausage, although most wealthy families made slaves do the hardest work in the kitchen. White women tried to preserve their culinary knowledge. Martha Dinsmore, a Kentuckian whose husband owned eleven slaves, kept recipe books for almost thirty years, collecting plant cuttings, newspaper articles, and recipes from family members. Inside the household, women performed ceremonial duties, as well. The oldest woman present, either the mother or the eldest daughter, sat at the head of the table during meals.15

White men, too, contributed to the household fare. Yeomen farmers and small-scale slaveholders worked hard in the fields, planting in the spring, tending crops in the summer, and harvesting crops in the fall. Some planters made agricultural experiments on their farms, breeding and raising different varieties of legumes. Most men learned to hunt and fish as boys, and adult men from all backgrounds practiced those skills. Yeomen farmers went hunting to supplement their diets, and attorney Maxcy Gregg, a sportsman, passed many hours hunting with his friends in coastal South Carolina. Another South Carolinian, planter Thomas Chaplin, loved the outdoors and plumbed the waterways for drum fish, sheepshead, and bass for his family’s table.16

Most white Southerners gladly shared their food with relatives and friends. Kinfolk gave each other gifts of fish, figs, and other comestibles, which they in turn shared with other family members, and some of them went to a lot of trouble. S. R. Eggleston sent a barrel of flour, a barrel of herring, and a bundle of fruit trees from his home in Richmond to his cousins in Claiborne County, Virginia. Female relatives exchanged gifts of food, proffering coffee for eggs, and women could be generous with their friends, as well. One South Carolinian, plantation mistress Keziah Brevard, made a steeple cake (a kind of sponge cake) for her neighbor’s wedding, even though she did not really approve of the match.17

The South’s cuisine included regional specialties such as grits and cornbread, Native American in origin, which dated back to colonial times. White Southerners employed some ancient implements in their preparation of meals. In Mississippi, plantation mistress Martha Maney kept a hominy mortar, used to separate corn kernels, in her kitchen. European influences survived in parts of the region. In Louisiana, local folk consumed jerked beef served in the so-called “French style,” the meat dried in strips and cooked over a smoky fire. White people also borrowed foodways from the black Americans in their midst, including methods of preparing rice that came from Africa to the Carolina low country by way of the Caribbean.18

White Southerners were enthusiastic carnivores, enjoying meat of all types. They consumed other kinds of protein, including seafood and freshwater fish, but they loved meat. The prosperous customarily ate more meat, and more than one type of meat, as Frances Kemble, an English-born plantation mistress, noted. She recorded helpings of duck, geese, turkey, and venison at the table. Other class differences appeared in the diet. Beef has long been the most prestigious meat, partly because beef cattle require a lot of acreage for grazing, so it was more common on a planter’s table. Yeoman farmers favored pork, which was a staple of the working-class diet, partly because pigs are easier and cheaper to raise.19

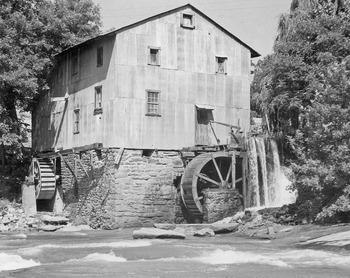

Bread was the staff of life, and the grain mills in the Old South both reflected and reinforced the ethos of communalism. In the fall, most residents took their corn or wheat to be processed at a local mill powered by animals – a mule treading in an endless circle – or water from nearby streams or bayous. So-called “combination mills” processed corn and lumber by turns, the wheels cleaned between rounds. The miller was an important figure in the community, essential to the food supply. William S. Blunt, the miller in Maumelle, Arkansas, charged a toll of one-eighth of the corn crops his customers brought in, and he sold cornmeal directly to the public. He developed a regular clientele and thanked them in the local newspaper for their patronage.20

On festive occasions, whites supped together to celebrate good fortune while simultaneously confirming their social ties. This, too, has been the case for many societies over the centuries. When relatives called on each other, lavish feasts were served as a gesture of welcome, and when longtime friends met, they marked the occasion, as Texan Branch T. Archer did, by bringing out Virginia fowl, Smithfield ham, and whiskey. The emphasis was on volume, heaps of food spread out on tables, and, during holidays, the elaborate presentation of food and drink. On New Year’s Day, one planter family in Florida set up in their parlor a table covered with decorative little cakes, a large punch bowl with a silver ladle, and patterned glasses for the guests as they streamed through the house.21

To be sure, some hungry white people lived in the South. Near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, beggars sometimes appeared at the door of wealthy households asking for something to eat, and when the winter was bad, neighbors occasionally stole food from each other. Conversely, some affluent people would not share their bounty with working-class whites, and they could be vicious in punishing thefts. When planter John Devereaux caught the young Andrew Johnson trying to steal some fruit from his property, he had the boy whipped. Families who were perpetually short on food could be charged with vagrancy, but relatives and neighbors were expected to share their provender with the less fortunate, and most of them did so.22

Timber

The same assumptions prevailed about the South’s forests, that there was plenty of timber for everyone, and that the woodlands should be shared. Evergreens, deciduous trees, hardwoods, and softwoods grew all over the region, the different species flourishing in different geographic zones: mixed hardwoods such as live oaks grew in the coastal sandy soil, while conifers appeared in the red clay of the Piedmont. The South was heavily forested when the first Anglo-Americans arrived in the 1600s, and the intervening centuries of settlement had cleared only a portion of the woodlands. The region included vast tranquil forests, tidy little groves, and ancient giants; the Oglethorpe Oak, planted by the Georgia colony’s founder in the eighteenth century, was still alive in the 1830s. Most white people saw the woodlands as an endlessly renewable resource, generating enough fuel for everybody. Planter James Avirett depicted the forest as inexhaustible.23

Most people believed that corridors of forests constituted an essential part of a pleasing landscape, and they engaged in a complex silviculture, drawing on their knowledge of forestry and their personal preferences. Boys began learning about timber when they were young. Robert Jones, the twelve-year-old son of a Virginia planter, impressed his tutor with his extensive knowledge of trees, their characteristics, and their financial value. In adulthood, men advised each other on which trees to plant and where to plant them, and they could develop fondness for a particular species on their own land. One yeoman farmer in South Carolina planted cedars on his property, and he would not cut them down even if they sprouted in his cotton fields. Women also acquired an extensive knowledge of trees, plants, shrubs, and flowers, as they devised their gardens and yards.24

Wood was an extremely valuable resource since it could be put to so many uses on a farm, to make homes, barns, stables, gin-houses, storehouses, plows, churns, and furniture. Timber was an essential fuel for the fireplace, in every household. Many white men assumed as John C. Cook did that forested acres were necessary to support a farm, so most planters and farmers purchased land that was at least partially wooded. They cleared some acreage every year for their own use, even as they planted more trees for future use. John J. Frobel planted hickory on his Virginia plantation as an investment, in case his descendants had to harvest it one day during hard times.25

Much of the wood went into building fences, which were necessary for the functioning of a farm economy. Fences marked property boundaries and kept livestock out of the fields, so crops could flourish. The zigzag fence – also known as the worm fence or the Virginia fence – was common in the antebellum South. To build a zigzag fence, a man had to cut rails and stack them, six to ten rails in a panel (or section), fit the panels together, and secure the panels by crossed poles. Water-resistant and rot-resistant wood, such as longleaf pine, cypress, cedar, or white oak, made the best fences, and winter was the right time of year to make rails, when the sap was down. The zigzag fence required as many as 26,000 rails for 4 miles of fence, but it was easy to fix and easy to move. Such a fence could be expected to last over thirty years. In the Old South, keeping fences in good repair was considered part of being a good neighbor.26

When men cut down trees, which was very hard work, they used a pole axe with a single sharp edge. They cut trees at waist-high height from the ground, notching trunks on the side where they wanted the trees to fall, and then chopping hard on the other side. Farmers chose smaller trees with trunks less than 2 feet in diameter, avoiding trees with knotted, twisty trunks. Clearing the woods off one acre of land usually took one man about thirty days of labor. Yeomen farmers did this work themselves, as did other white men, such as minister Francis McFarland and editor Joseph Waddell, both Virginians. Some slaveowners did woodwork themselves, trimming trees in their yards, although they spared themselves the hardest labor. That work was performed by slaves or white men employed by the master.27

The forest offered a host of medicinal and pharmacological benefits, as well. White Southerners drew on a large body of folk knowledge about trees and shrubs accumulated by both races. White people saved the roots from certain trees, including may apple and black haw, for their healing powers, and they published books such as The Planter’s Guide and Family Book of Medicine (1848), which suggested an infusion with leaves of the mountain ash as a treatment for typhus. Some whites shared the ancient folk belief that trees could by their very presence ensure good health. Planter Thomas Dabney of Mississippi put a wide belt of trees around his residence to protect his family from illness, and most people agreed that pine forests were particularly healthy.28

The appreciation of the forest’s medicinal benefits coexisted with a pragmatic knowledge of how to make money from the woodlands. The timber business across the South could be very profitable. Cypress shingles cut from forests in North Carolina sold well in the North, and the turpentine and naval stores business thrived in the state for most of the antebellum era. All over the region, timber growing near a river was deemed especially valuable because it could be transported easily on the water or sold to steamboat companies. White Southerners with an entrepreneurial bent perceived the forest as a way to get rich. One attorney purchased 750 acres of white oak in Kentucky and reckoned he could earn 10,000 dollars a year by making staves from the wood.29

Because the region’s woodlands seemed inexhaustible, white Southerners could be careless with timber. Some planters were known to let diseased trees decay on their land, “defacing” the countryside, in the view of one Alabaman, while turpentine workers left the gouged trunks of pine to rot and collapse. Citizens from all backgrounds cut down too many trees, which caused eyesores of unsightly stumps and contributed to soil erosion and soil exhaustion. Some white Southerners decried the recklessness of their fellows. In Covington County, Mississippi, Duncan McKenzie criticized the poor management of land and everything that grew on it by his neighbors, who wasted everything “precious.”30

Many white Southerners nonetheless cherished trees, which have always provided emotional comfort to human beings beyond their practical benefits. They often engaged in their own landscape design. Samuel W. Leland, a doctor in Richland County, South Carolina, planted fifteen elms on the avenue in front of his house, and he did not want them to ever be cut down. Sally Jane Hibberd, a yeoman farmer’s daughter, derived pleasure from the honeysuckle and woodbine entwined around the porch at her aunt’s Virginia home. Because of the ancient custom of carving names on their trunks – what are called arborglyphs – trees could also serve as historical documents of a sort. In northwest Georgia, local people carved their names by the hundreds in some old trees on the Bitting property.31

White people did not have to be rich to love the forest, in any part of the region. Kate Plake, who hailed from a modest family in Bath County, Kentucky, loved to wander through the woods near her house, and Lizzie Jackson Mann, a minister’s daughter, delighted in strolling with her relatives through the forest in Gloucester County, Virginia. Citizens of all backgrounds who grew up in the piney woods of antebellum Mississippi felt nostalgic for the forests of their childhoods. Some people held to an older mentality, a fear of the wild woods, but the more romantic nineteenth-century view of the forest as a bower of repose and beauty seems to have prevailed.32

Most white Southerners assumed that there was plenty of wood for everyone. They followed the custom of lifting the occasional fence rail in their neighborhoods for their own use, and travelers cut trees from the roadside without asking anyone’s permission if they had to repair a wagon; steamboat crews routinely took wood from river banks, paying on the honor system by slipping money into boxes nailed on trees. The national government tried to halt the “round forty,” when squatters took wood from public land, and some private landowners prosecuted individuals for cutting wood on their property, but many white people took it for granted that there was enough timber and that everyone should have access to the woodlands.33

Habitat

The most important building in the landscape was the private dwelling, laden with cultural meaning as a refuge and a sanctuary. In this enclosed domestic space, a place set apart, they were supposed to be protected from all hazards. Here the landmarks of private life registered, as kith and kin witnessed weddings, celebrated childbirths, and grieved for the dead. Here they entertained guests, enjoying a robust social life with neighbors and friends. For many white Southerners, including yeomen farmers, their childhood homes had what Albert Blue called “sacred” associations. In adulthood, they loved the homes where they resided with the same fervor. Sarah H. Brown, a slaveholder’s wife, said that when she returned from a trip, her house in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, looked more beautiful than ever.34

The home’s placement in the countryside mattered, too, for the purposes of good health and visual effect. In the countryside, most white Southerners perceived hilltops as healthier than lowlands, so that is where the affluent put their houses. Yeomen tended to live on less desirable lots on sandy soil that did not produce the best crops. Trees around an edifice served as windbreakers, although the home should not be built too close to a body of water, which could breed mosquitoes, as one South Carolinian discovered. The structure, known afterwards as “Mr. B.’s Folly,” had to be abandoned after three months because he chose an unhealthy location for his house. Most people had specific ideas about spatial organization outside the house, too, expecting that the yard should be filled with trees, shrubs, and flowers.35

When most white Southerners constructed their homes, they used local woods of different types and vernacular designs, building homes that were one room deep, two rooms long, and two stories high, or two cabins connected by a walkway or dogtrot. The affluent employed professional architects in tune with national trends who produced larger buildings in the Federal or Italianate style, while yet others made their own idiosyncratic variations. E. M. Perine, a merchant, added a vestibule with a turret to the front of his brick mansion in Cahaba, Alabama. Some whites designed their houses themselves, putting a lot of time, thought, and energy into the plan. Mary and William Starnes planned a six-room structure with four fireplaces and a piazza for their residence in Limestone County, Texas.36

In the construction of their houses, slaveowning men frequently used their bondsmen, while others hired white men or free black men. Mead Carr paid white men to put up his residence, an ordinary frame building 18 by 20 feet, in rural Missouri. Yet other slaveholders did some of their own work, building the chimneys themselves. Yeomen farmers, artisans, and schoolteachers constructed log cabins of one or two rooms, and they stood ready to help their relatives and neighbors build their homes. About eighty logs were necessary to build a log cabin, and, depending on the number of workers, it could be completed in one to three days. Other white men were expected to assist in some way, and anyone, regardless of wealth, who failed to pitch in could be perceived as arrogant.37

The oldest homes dated from the eighteenth century, some of them built in the Georgian style, such as Berkeley, a three-story brick residence constructed on the James River in 1726. Other planters lived in domiciles that originated in the early nineteenth century as log cabins, which they expanded to include porches and second stories and later covered with clapboard. Some whites were very proud of their aged homes. John Wyeth’s birthplace in Marshall County, Alabama, stood for forty years before 1861, and he hoped the building would last another hundred years. Houses could stay in the same family for multiple generations, which was one way to conserve a material resource. Duncan Blue, a turpentine farmer in Cumberland County, North Carolina, lived in the building that once belonged to his grandfather.38

Planter mansions, although few in number, dominated the landscape. Set back from the road on hilltops, constructed of brick or wood, they had to be approached via long lanes bordered with trees. These estates were intended to do more than provide a haven for the owners: they reflected their wealth and advertised their elite status. In Bledsoe County, Tennessee, Lee Billingsley recalled, his father built a brick mansion of twelve rooms. White-pillared mansions constructed in the Greek Revival style were popular for their formality, symmetry, and visual splendor, and for practical reasons, since the colonnades kept the buildings cool in hot weather. Plantation homes had many rooms constructed with the “best materials,” one owner asserted, and mansions could cost several thousand dollars, far beyond what the average white Southerner could afford.39

Inside their houses, white Southerners of all backgrounds kept a mélange of objects, some of them necessary, others merely decorative, some of them handmade, and others store-bought. Many of these objects were utilitarian, necessary for daily life, such as the fishing tackle and medicine chest displayed in an overseer’s house in South Carolina. People of all social classes had belongings that had no function other than pure pleasure. Harriet Vann, a yeomen farmer’s wife in Chesterfield County, South Carolina, counted among her possessions a violin. Yet other objects, not necessarily expensive, gave solace to the occupants. Mary Ann Cobb, a congressman’s wife, relished the “warm looking” cotton carpet, calico curtains, and bookshelves in her home in Athens, Georgia. The mansions of the wealthy included such luxury objects as mahogany bedsteads and other markers of a consumer culture that elites had joined in the late eighteenth century.40

The home was a memory hoard, replete with beloved objects that represented the family history. Many whites saved their Bibles, and men typically left them, with other “family books,” to their wives and daughters in their wills. In fact, women frequently served as curators of the family’s material history. They collected daguerreotypes of their relatives, preserved in elaborate frames, and they saved correspondence from previous generations, irreplaceable documents of their own history. The sentimental value of these material objects, even the most mundane, could be enhanced over time. As the decades went by, something useful like a spinning wheel could be transformed into an heirloom. Some women felt a powerful connection to the objects displayed inside the house. Ellen Wallace, a Kentuckian, visited her parent’s home after they died, and the inanimate objects “shout aloud as I pass,” she wrote.41

Whites of all social backgrounds felt love for their homes and the objects within the house. Georgian A. E. Harris, whose husband owned a few slaves, thought their log cabin was quite “pretty,” and other whites drew their own conclusions about neighborhood buildings. In Mississippi, Letitia Dabney Miller admired her rich uncle’s house with its ornate furnishings, but she did not think it very comfortable, and she preferred her own more modest abode. The loss of a house, regardless of its status, size, or age, could be deeply unsettling. Physician Hardy Wooten felt depressed when he stopped by his childhood home in Burke County, Georgia, to find the building deserted and the yard turned into a cornfield. The vacant dwelling and furrowed ground made him feel severed from his past.42

Not every white Southerner cared so deeply for their homes, however, as John Graydon observed. Some of his neighbors in Alachua County, Florida, simply threw their houses together and took no pride in the buildings. Other people neglected the condition of the home. Farmer Hugh McLaurin acknowledged that the “Old House” where he lived with his wife had fallen into “a State of Decay,” so he left money in his will for his sons to fix it if they wished. Most communities had a few abandoned houses. In Hardeman County, Tennessee, several empty houses stood, the buildings left empty in 1860 for reasons we cannot discern. But the owners probably departed under duress, since a house of any kind was a valuable material asset.43

Politics and War

Politics had always been a vital part of community life, a manifestation of both neighborly bonds and energetic competition. Candidates from the mainstream parties, the Democrats and the Whigs, campaigned with zeal, hosting parades, dinners, and serenades. Throughout the South, neighbors came to barbeques to hear speeches from candidates for county offices, as rivals made mostly good-natured jibes at each other. Local races could be very personal. William Kinney of Staunton, Virginia, knew a lot about the candidates for his district’s state senate seat in 1857, their strengths, their shortcomings, and the names of their friends and foes. Politics was reserved for white men, since white women did not vote anywhere in the United States, and most people considered it unseemly for white females to show much interest in political matters. Some white men, too, were apolitical, although they of course could vote.44

In the mid-1850s, after the Whig Party disintegrated and the Republican Party formed, questions related to slavery moved front and center in the national discourse. Many white Southerners began to assume that all white Northerners were different from themselves, not just on issues pertaining to slavery or race but on every issue, as if they were an alien people. Robert H. Armstrong, traveling by boat from Memphis to New Orleans in the 1850s, evoked what he saw as a distinctly Southern communalism as he complained about the Yankee families on board. They were unsociable, with none of the “warm gushing of feeling and sympathy” that Southerners exhibited; instead, “all was cold, hard, real.” Despite Armstrong’s complaints, the two regions actually had much in common. Most of the white Northern population lived in rural, small-town communities that featured a rich social life, and like the South, that included both cooperation and conflict. They approached material resources in much the same way, with the same mix of stewardship and carelessness. They ate a somewhat different diet, with more helpings of clam chowder than people consumed in Dixie, but they too savored lots of meat, and they agreed that food should not be wasted. They found trees in a rural landscape pleasing to the eye, and they harvested the forests for the same diversity of purposes, sometimes leaving behind eroded, damaged soil. They loved their homes, whether they lived in log cabins, frame houses, or spacious mansions, and their dwellings contained a range of purchased and handmade objects that brought enjoyment to the owners.45

The presidential election of 1860 opened unbridgeable political differences not only between North and South but also within the white Southern population. Four candidates ran, posing different answers to the overriding question: Should slavery expand into the trans-Mississippi West? In the South, the race mostly came down to a contest between the Southern Democrat John Breckinridge, who argued that the slave states should consider secession if anyone tried to stop slavery’s expansion, and the Constitutional Unionist John Bell of Tennessee, who stated that all political issues should be decided within the existing government. (The Republican Abraham Lincoln, who opposed the expansion of slavery, and the Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas, who believed that the decision should be made at the territorial stage, did not attract many votes in the region.) Most people understood the election’s significance, with secessionists threatening to leave the country if Lincoln won. Breckinridge took the Deep South, while Bell carried three states in the Upper South – Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee – and won impressive support in states taken by Breckinridge, such as Alabama, where Bell garnered a third of the vote, and North Carolina, which Bell lost by fewer than 4,000 votes; he lost Missouri to Douglas by fewer than 500 votes. Bell, whom many historians have dismissed or forgotten, took about 40 percent of the vote in the slave states (the Border States and the future Confederacy). As South Carolina launched itself out of the Union in December 1860, the white population in the slave states was deeply divided on the wisdom of secession.46

The turbulent political debate continued into the spring, as secessionists went on the offensive. Local firebrands created vigilance committees to examine their neighbors on their political views, and they monitored the behavior of anyone who might be opposed to secession. Every Southern state contained whites loyal to the Union, and they in turn held public meetings and signed petitions. Historians still do not know how civilians chose sides. Many working-class people felt ambivalent or hostile toward secession because they resented the planter elite, while others had kinfolk in the North. Some citizens of all backgrounds, including slaveholders, opposed secession because they too had Yankee relatives; others thought secession was illegal, unreasonable, an appeal by demagogues, or a betrayal of the Revolution; yet others still loved the Union, adhered to the old Whig Party, or opposed war itself. Maybe the choice came down to attitudes toward risk, for secession was if nothing else an enormous risk. But regardless of how they made their choices, neighbors started to turn against each other, and longtime friendships ended. The communalism of the past, carefully nurtured by so many people, began to fall apart. By April 1861, seven states had formed a new country, the Confederacy.47

Secession might bring war, as many Americans realized, and as white Southerners weighed that prospect, most of them had little understanding of how destructive a war could be. The generation that served in the Revolution had passed away, and public memory focused on the glorious victory over the British rather than the war’s damage to civilians or their resources. The Mexican War, which lasted only two years, was fought mostly outside the South. The War of 1812 did take place in the region, and some inhabitants did remember the harm it inflicted on the material world. William Chamberlaine’s grandmother, who lived through that war, told her family that civilians should remain in their houses until the shingles flew off so they could protect them from the armies. A few other voices warned of trouble ahead. David Strother’s father, a Virginian who served in the War of 1812, predicted that it would take several years to turn volunteers into responsible soldiers. But most young men knew about war only from reading books, rebel soldier William L. Sheppard later admitted, and most white Southerners were dangerously naive about a war’s impact on civilians and the material framework they needed to survive.48

When war was officially declared after the shelling at Fort Sumter, the acrid political climate inside the South deteriorated even further. Confederates interrogated neighbors whom they feared might be pro-Union, opened their mail, threatened them, and forced them out of their homes. Soon they resorted to violence, burning down houses and shops belonging to Unionists. Anyone who seemed opposed to the Confederacy or even reluctant in their support now became suspect. The political crisis reached into the family, turning relatives against each other. Some Unionists – but not all – fell silent. Other people, indifferent to politics or afraid of antagonizing their neighbors, tried to avoid taking sides.49

The growing turmoil prompted hundreds of white people to leave the South. After April 1861, pro-Union citizens departed because of friendly warnings from neighbors who believed they might be hurt, while others fled because their property was seized by the newly created rebel government, or because they refused to take loyalty oaths to the Confederacy. Not until August 1861 did the Confederate Secretary of War begin to require passports, and then only in some locations, so people could travel out of the South for months after Fort Sumter. Where pro-Union sentiment was tenacious, the reverse happened: pro-Confederate residents fled such Unionist strongholds as eastern Tennessee.50

The white people who remained behind were about to live through a series of quick transformations in attitudes toward people and things. The imperatives of war took over, war, that deadly business that would exploit almost all of society’s human resources and material resources. Troops in both armies developed new assumptions about the resources they needed to survive, a rapid shift in outlook by white men from the South and North who had practiced communalism and stewardship at home. This seems to have taken place immediately, in the first weeks of the conflict. The population was sorted into new two categories, civilian and military, with new identities, new roles, and diverging ideas about resources. Civilians with strong political loyalties proved to be willing to take action to help the respective causes, while others were more interested in self-preservation. In the spring of 1861, a terrific struggle broke out over the region’s resources, starting with the people themselves.