Introduction

Silverleaf nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav.) is an aggressive, highly persistent, invasive species that adversely impacts agricultural and rangeland productivity by competing with crops for nutrients and water, exuding allelopathic compounds that inhibit crop growth, and hosting destructive phytophagous pests and pathogens (Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, Murray and Tyrl1984; EPPO 2007). The invasiveness of the species is attributed to its ability to reproduce sexually via insect pollination and asexually through regenerative buds in the roots and stem fragments. Various cytotypes including diploids (2n = 24), tetraploids (2n = 48), and hexaploids (2n = 72) have been reported in Argentina, although S. elaeagnifolium specimens in the United States have been identified as diploids (Heap and Carter Reference Heap and Carter1999; Scaldaferro et al. Reference Scaldaferro, Chiarini, Santiñaque, Bernardello and Moscone2012). It is native to northeastern Mexico and the southwestern United States but has since spread across 21 states in the United States and 42 countries throughout Asia, South America, and Australia (Mekki Reference Mekki2007; Roche Reference Roche1991). In the United States, sizable yield losses in cereal, fiber, vegetable, and forage crops have been attributed to S. elaeagnifolium infestation (Boyd et al Reference Boyd, Murray and Tyrl1984; Brandon Reference Brandon2005).

Anthropogenic activities have greatly contributed to the widespread distribution of S. elaeagnifolium, although the successful establishment of the species outside its native range suggests an inherent mechanism underlying its adaptability to heterogeneous environments (Boyd and Murray Reference Boyd and Murray1982; EPPO 2007; Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Heap, Carter, Wu and Panetta2009). A key facet to the adaptive success of invasive species in response to environmental alterations is their fitness flexibility as conferred by phenotypic plasticity and genetic adaptation. Phenotypic plasticity is an adaptive strategy that allows a species to buffer rapid changes in the environment by altering its phenotypic attributes, including morphology, growth, survival, and fertility (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Jennions and Nictra2011; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Bossdorf, Muth, Gurevitch and Pigliucci2006). In the short term, phenotypic plasticity has the ability to enhance the survival of small populations but, in so doing, it reduces the effectiveness of natural selection in promoting genetic adaptation. In the long term, phenotypic plasticity may not be sufficient for a species to avoid extinction (Moritz and Agudo Reference Moritz and Agudo2013; Nunney Reference Nunney2016). Conversely, genetic adaptation is the rapid selection of adaptive phenotypes and is facilitated by high levels of genetic variation (Barret Reference Barret2015). This mechanism usually requires strong, divergent selection pressures such as temperature, precipitation, and latitudinal clines (Kollman and Bañuelos Reference Kollman and Bañuelos2004; Rice and Mack Reference Rice and Mack1991).

From a management perspective, both phenotypic plasticity and genetic adaptation contribute to the successful establishment and survival of an invasive species outside its native range. Studies that considered the relative importance of both mechanisms in the adaptive success of invasive species indicate that they are not mutually exclusive (Geng et al. Reference Geng, van Klinken, Sosa, Li, Chen and Xu2016; Si et al. Reference Si, Dai, Lin, Qi, Huang, Miao and Du2014). Indeed, ecological and genetic research on introduced S. elaeagnifolium populations in Australia and Europe showed a high degree of genetic variation and evidence of morphological plasticity in the species in response to variable water availability (Travlos Reference Travlos2013; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wu, Stanton, Burrows, Lemerle and Raman2013c). Relative to phenotypic plasticity, however, genetic adaptation will have a larger effect on the long-term efficacy of a strategy intended to control invasive species. For example, an S. elaeagnifolium population with high genetic variability will have the genetic means to develop tolerance to a particular herbicide in the long term compared with an S. elaeagnifolium population with low genetic variability. High genetic variation also translates into genotype variability within a population. When a biological strategy is used to manage S. elaeagnifolium, biological control agents may exhibit differential survivability across genotypes, and therefore different efficiencies for control. Understanding the extent of genetic variation that drive the long-term, evolutionary adaptation of S. elaeagnifolium will facilitate the design of effective methods to control this weed.

Genetic variation can be quantified based on the amount of genetic polymorphism or heterogeneity present among and within individuals of different populations of a given species (Geng et al. Reference Geng, van Klinken, Sosa, Li, Chen and Xu2016; Sakai et al. Reference Sakai, Allendorf, Holt, Lodge, Molofsky, With, Baughman, Cabin, Cohen, Ellstrand, McCauley, O’Neil, Parker, Thompson and Weller2001). Several molecular marker systems, including amplified fragment-length polymorphism (Vos et al. Reference Vos, Hogers, Bleeker, Reijans, van de Lee, Hoernes, Frijters, Pot, Peleman, Kuiper and Zabeau1995), random amplified polymorphic DNA (Penner Reference Penner and Jauhar1996; Welsh and McClelland Reference Welsh and McClelland1990; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Kubelik, Livak, Rafalski and Tingey1990), insertions/deletions (indels) (Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Paredes, Ferreira, Gutiérrez and Díaz2017; Jain et al. Reference Jain, Roorkiwal, Kale, Garg, Yadala and Varshney2019; Jamil et al. Reference Jamil, Rana, Ali, Awan, Shahzad and Khan2013; Tu et al. Reference Tu, Lu, Zhu and Wang2007), simple-sequence repeats (SSRs) (McCouch et al. Reference McCouch, Chen, Panaud, Temnykh, Xu, Cho, Huang, Ishii and Blair1997; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Machray and Provan1996; Taramino and Tingey Reference Taramino and Tingey1996), and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (Govindaraj et al. Reference Govindaraj, Vetriventhan and Srinivasan2015), have been successfully used to assess the intra- and interspecific variation in various plant species.

Despite genetic diversity studies on introduced S. elaeagnifolium populations in different geographic locations, including Europe, Australia, and South America (Chiarini et al. Reference Chiarini, Scaldaferro, Bernardello and Acosta2018; Qasem et al. Reference Qasem, Abdallat and Hasan2019; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2012, Reference Zhu, Raman, Wu, Lemerle, Burrows and Stanton2013a, Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2013b), the available genetic marker resource for the species remains limited. Previous research to evaluate the transferability of SSR markers from related Solanum species identified 13 out of 35 SSRs that can amplify targets in S. elaeagnifolium, although only 6 were polymorphic. Using these 6 markers, a high degree of genetic variation was established in naturalized populations of S. elaeagnifolium in Australia (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2012). In a separate study, 26 SSR primer pairs were designed based on expressed sequence tags and genomic sequences of S. elaeagnifolium (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Raman, Wu, Lemerle, Burrows and Stanton2013a). Of the 26 SSR markers, only 9 were polymorphic. These 26 SSRs represent the first set of SSR markers that has been developed specifically for S. elaeagnifolium (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Raman, Wu, Lemerle, Burrows and Stanton2013a).

To accurately assess the extent of genetic variation that defines the ability of S. elaeagnifolium to adapt successfully to different environments, a core set of molecular markers that can capture informative variation across the genome needs to be developed and validated for their applicability in genetic diversity studies. While a few SSR markers have been generated and used to assess the extent of genetic variation in introduced S. elaeagnifolium populations in countries such as Australia and Jordan, it is yet undetermined whether these markers are sufficient to capture the genetic variation within the S. elaeagnifolium genome, or if they will successfully transfer to S. elaeagnifolium populations beyond these two introduced ranges as well as within the species’ native range. The goal of this study, therefore, was to expand the genetic marker resource that can be used for genetic diversity studies in S. elaeagnifolium. This was accomplished by establishing the transferability to S. elaeagnifolium of SSR and indel-based markers from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) and Solanum lycopersicoides Dunal and determining the applicability of cross-transferable DNA markers in assessing the extent of genetic variation in S. elaeagnifolium populations from different localities within the native range of the species in Texas, USA. The ability of SSR markers that have been reported to amplify targets in naturalized populations of S. elaeagnifolium in Australia to genotype S. elaeagnifolium populations from the United States was also evaluated.

Materials and Methods

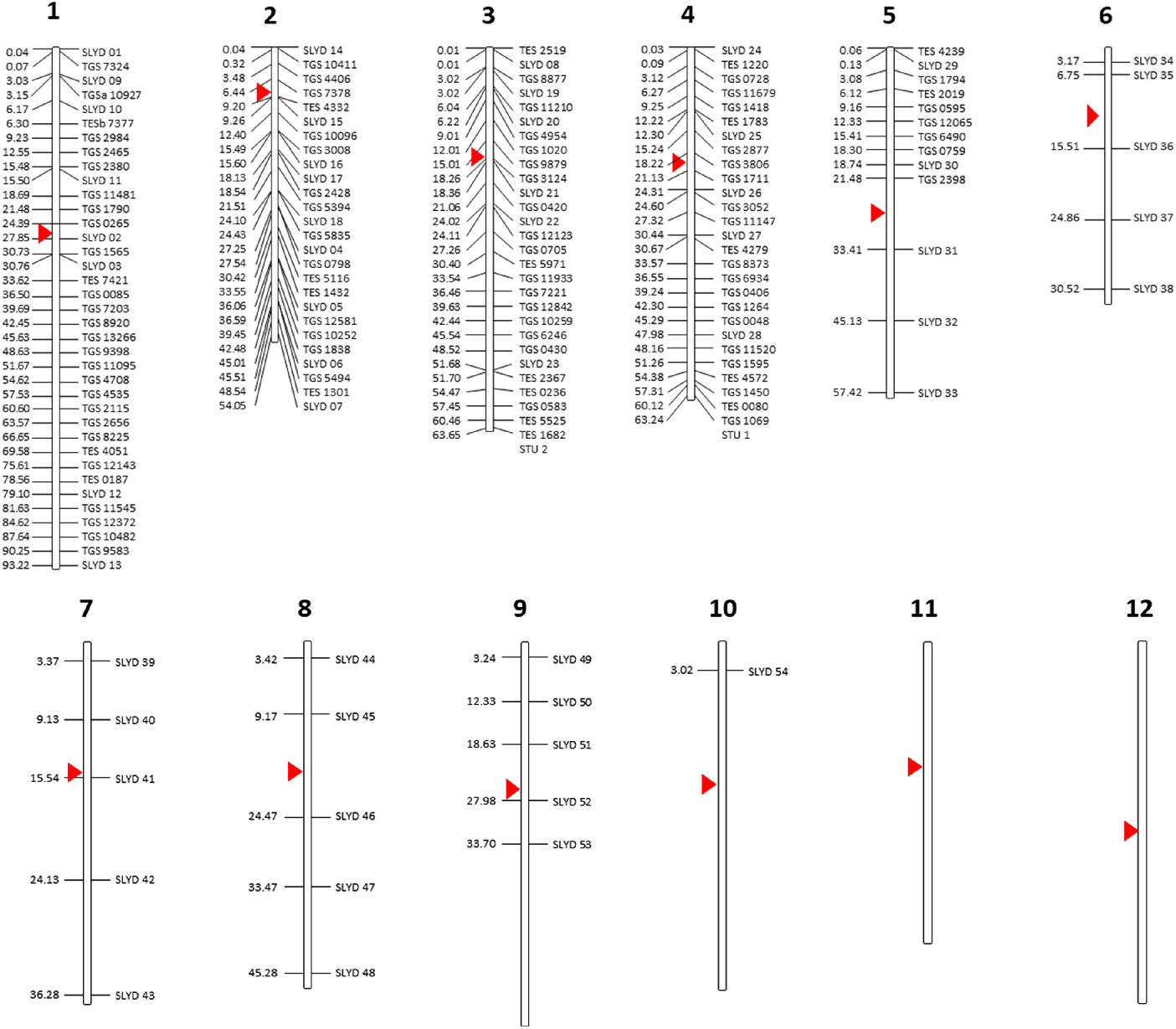

Transferability of Solanum spp. DNA Markers to Solanum elaeagnifolium

A total of 187 DNA markers, including 98 genome- and expressed sequence tag (EST)-based SSRs specific to tomato and 54 indel markers specific to S. lycopersicoides were screened for their ability to amplify target sequences in the S. elaeagnifolium genome. The selected markers mapped in chromosome 1–10 of the tomato genome and did not include markers targeting chromosomes 11 and 12 (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S1). All tomato SSRs were synthesized based on publicly available primer sequences from the Kazusa Marker Database (http://marker.kazusa.or.jp/Tomato), whereas the S. lycopersicoides–specific DNA markers were designed following specifications for standard primer design using an in-house analysis of a draft assembly of the S. lycopersicoides genome. Twenty-six SSR markers specific to S. elaeagnifolium, two specific to potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and seven specific to eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) and that have been identified to amplify targets in S. elaeagnifolium populations in Australia (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2012, Reference Zhu, Raman, Wu, Lemerle, Burrows and Stanton2013a) were also screened for their applicability to genotype populations of S. elaeagnifolium from the United States (Supplementary Table S1). Synthesis of all DNA markers were outsourced to Sigma (Woodlands, TX, USA).

Figure 1. Solanum-based DNA markers that were screened for their transferability to Solanum elaeagnifolium. All markers were mapped against the tomato chromosome as a point of reference. Numbers on the left indicate the estimated physical distance (Mb) of each marker along the length of each chromosome. Red triangle indicates the centromere.

Genomic DNA was isolated using a modified CTAB method (Murray and Thompson Reference Murray and Thompson1980) from six individual S. elaeagnifolium plants that were randomly collected from the Horticultural Gardens of the Department of Plant and Soil Science of Texas Tech University (TTU), Lubbock, TX. SSR and indel targets were amplified from the extracted DNA samples following a standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol (Shim et al. Reference Shim, Torollo, Angeles-Shim, Cabunagan, Choi, Yeo and Ha2015). PCR amplicons were resolved in 3% agarose gel in 1X Tris-borate-EDTA buffer.

Solanum elaeagnifolium Populations

Mature berries from natural populations of S. elaeagnifolium were harvested in January 2019 from 100 m by 100 m quadrats in Lubbock (33.58°N, 101.85°W), Littlefield (33.92°N, 102.3°W), and Blackwell, TX (32.09°N, 100.32°W) (Figure 2) and used as sources of seeds. The collection sites in Lubbock included an experimental farm planted mostly with cotton and a native rangeland maintained by TTU. The collection site in Littlefield is a rangeland maintained under a Conservation Reserve Program, and the site in Blackwell is a hunting reserve with interspersed wheat plantings.

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of Solanum elaeagnifolium populations used in the genetic diversity analysis. Seeds of S. elaeagnifolium were collected from mature plants from Lubbock, Blackwell, and Littlefield, TX.

Seeds were collected from berries that were harvested from each site and air-dried for 72 h in petri dishes lined with paper towel under greenhouse conditions (ambient temperature of 28 C). The seeds were then directly sown and germinated in plastic flats containing conventional potting media (containing 45% to 50% of composted pine bark, vermiculite, Canadian sphagnum, peat moss, perlite, and dolomitic limestone) or a mixture of sand and potting media (1:1 ratio) without any fertilizer input. The plastic flats were lined with 2-mm polypropylene plastic sheets with 1-cm holes to allow proper drainage after watering every 3 d. All experiments were carried out in a greenhouse of the Horticultural Gardens of TTU.

At the two-true-leaf stage of the seedlings, leaf tissues were sampled for DNA extraction using a Tris/HCl-potassium chloride-EDTA buffer (Angeles-Shim et al. Reference Angeles-Shim, Reyes, Del Valle, Sunohara, Shim, Lapis, Jena, Ashikari and Doi2020). A total of 147 individual plants from the Lubbock experimental farm (33) and rangeland (52), Blackwell hunting reserve (44), and Littlefield rangeland (18) were genotyped for genetic diversity assessment.

Genetic Diversity Analysis

DNA markers identified to amplify targets in the S. elaeagnifolium genome (Supplementary Table S2) were used to assess the genetic diversity between and within populations of S. elaeagnifolium from Texas, USA. PCR and resolution of amplicons in agarose gel were carried out as described earlier. PCR amplicons were scored codominantly based on molecular weight differences.

Descriptive statistics for the single-locus DNA markers, including the number of different alleles (N a), number of effective alleles (N e), and expected heterozygosity (H e), were generated using GenAlEx v. 6.5b3 (Peakall and Smouse Reference Peakall and Smouse2012). Polymorphism information content (PIC) of each individual SSR allele was calculated using the formula PIC = ∑ p i2, where p i is the frequency of the ith allele in the genotypes tested (Weir Reference Weir1990). A genetic distance matrix based on the DNA marker profiles was generated using GenAlEx v. 6.5b3 and used to calculate both fixation (F-statistics) and similarity indices. F-statistics, including the average, pairwise genetic differentiation estimates between populations (F ST), as well as inbreeding coefficients (F IS and F IT), were assessed by analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) based on 9,999 permutations in GenAlEx v. 6.5b3. Similarity indices were calculated based on Jaccard’s coefficient. Genetic divergence among the experimental materials was determined by clustering analysis using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) subroutine in the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software based on 1,000 bootstraps (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Tamura and Nei1994).

Results and Discussion

Transferability of Solanum lycopersicum– and Solanum lycopersicoides–specific DNA Markers to Solanum elaeagnifolium

Of the 98 tomato-based SSRs screened for cross-species transferability, 28.57% amplified targets in the S. elaeagnifolium genome (Table 1). Previous reports on the interspecific transferability of SSRs have been unpredictable at best, with the ability of SSR markers to amplify targets in genomes of species within the same genus ranging from 16.5% to more than 50%, depending on the plant species (Angeles-Shim et al. Reference Angeles-Shim, Vinarao, Balram and Jena2014; Hernández et al. Reference Hernández, Laurie, Martín and Snape2002; Mullan et al. Reference Mullan, Platteter, Teakle, Appels, Colmer, Anderson and Francki2005). SSRs are tandemly arranged, repetitive sequences that make up a significant portion of the eukaryotic genome. They are hypervariable and have undergone extensive expansion or contraction throughout the course of evolution while simultaneously effecting changes in the nucleotide sequences flanking them (Temnykh et al. Reference Temnykh, DeClerck, Lukashova, Lipovich, Cartinhour and McCouch2001). In tomato, these genomic events, combined with mutations, transposon amplifications, chromosomal rearrangements, and gene duplications that also led to the domestication of the species would have generated genomic regions that are highly diverged from those of S. elaeagnifolium. The genomic divergence of tomato from S. elaeagnifolium would contribute to the low transferability of tomato SSRs in S. elaeagnifolium.

Table 1. Frequency of Solanum-based DNA markers that transferred and amplified polymorphic targets in Solanum elaeagnifolium populations from Texas, USA.

a Abbreviations: EST, expressed sequence tag; indels, insertions/deletions; SSRs, simple sequence repeats.

b EST-based tomato SSRs.

c EST-based, S. elaeagnifolium-specific markers designed by Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Raman, Wu, Lemerle, Burrows and Stanton2013).

d Potato SSRs screened for transferability to S. elaeagnifolium by Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2012).

e Eggplant SSRs screened for transferability to S. elaeagnifolium by Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2012).

Compared with the genome-based SSRs, a higher number of the EST-based tomato SSRs amplified targets in S. elaeagnifolium. EST-based markers are specific to transcribed regions of the genome and are generally more conserved across species (Kuleung et al. Reference Kuleung, Baenziger and Dweikat2004; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wei, Yan and Zheng2007). The higher transferability of the EST-based SSRs compared with the genome-based SSRs supports the evolutionary conservation of transcribed regions in the plant genome, specifically among species within a genus.

Of the 54 S. lycopersicoides indel markers that were screened for their cross-species transferability, only 18 amplified targets in S. elaeagnifolium (Table 1). SLYD 52, which maps at chromosome 9 of S. lycopersicoides, amplified multiple loci in S. elaeagnifolium. The fragment size generated by the 18 indel markers ranged from 143 to 380 bp, consistent with the in silico predictions for amplicon size.

Phylogenetic and monophyletic analyses of Solanum spp. have grouped S. lycopersicoides to the potato clade and S. elaeagnifolium to the Leptostemonum clade (Stern et al. Reference Stern, Fátima, Bohs and Bohs2011). The high degree of genetic differentiation that separated the two Solanum spp. into different clades may account for the <40% transferability of S. lycopersicoides indel markers to S. elaeagnifolium. Nevertheless, the results of the study indicate the presence of conserved binding sites for indels between S. lycopersicoides and S. elaeagnifolium.

Other Solanum-based SSR markers that have been previously reported to amplify targets in naturalized populations of S. elaeagnifolium from Australia (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2012, Reference Zhu, Raman, Wu, Lemerle, Burrows and Stanton2013a) were also screened for their ability to genotype S. elaeagnifolium populations from the United States. Except for SEA 13 and SEA 26, all S. elaeagnifolium markers, along with the two potato SSRs and six out of the seven eggplant SSRs, were able to amplify targets in S. elaeagnifolium from the United States. Markers that required a 58 C or 50 to 60 C annealing temperature to amplify targets in the Australian S. elaeagnifolium populations gave clear, consistent bands when amplified at an annealing temperature of 55 C using the samples from Texas. The size of the amplified fragments ranged from 220 to 340 bp, consistent with the range of amplicon size obtained from Australian S. elaeagnifolium populations (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2012). SEA 3 and SEA 16, which did not amplify in Australian S. elaeagnifolium populations, amplified multiple alleles in S. elaeagnifolium populations from the United States, whereas SEA 7 and SEA 22, which amplified multiple loci in the Australian S. elaeagnifolium populations, amplified a single locus in U.S. S. elaeagnifolium populations. Differences in the ability of the SEA SSRs to amplify targets in the Australian and U.S. S. elaeagnifolium populations, as well as in the number of target loci the markers can amplify, suggest a possible diversification of the Australian population following multiple introductions of the species from 1901 to 1914 (Cuthbertson et al. Reference Cuthbertson, Leys and McMaster1976).

Despite the rapid advances in sequencing and genotyping platforms, SSRs remain a marker of choice for most laboratories because of their cost-efficiency, abundance in the genome, degree of polymorphism, and reproducibility across laboratories (Collard et al. Reference Collard, Jahufer, Brouwer and Pang2005, Reference Collard, Vera Cruz, McNally, Virk and Mackill2008). In the current study, the observed, overall transferability to S. elaeagnifolium of DNA markers that are specific to other Solanum spp. was moderate (41.71%). This is expected, given the genetic differentiation of S. elaeagnifolium that separates the species from tomato and S. lycopersicoides. Despite this, the DNA markers that were identified to amplify targets in S. elaeagnifolium constitute valuable additions to the genetic marker resource that can be used for genetic studies in S. elaeagnifolium. To obtain a better coverage of the S. elaeagnifolium genome, Solanum spp.–specific DNA markers with targets in chromosomes 11 and 12 can also be evaluated for cross-species transferability and application in assessing genetic variation in S. elaeagnifolium. Additionally, sequencing and assembly of the whole genome of S. elaeagnifolium will provide a basis for species-specific primer design that can significantly expand the marker resource for S. elaeagnifolium.

Descriptive Statistics of DNA Markers Used in Genetic Diversity Assessment Studies

Of the 78 DNA markers used to genotype the S. elaeagnifolium populations, 50 consistently amplified clear bands in more than 60% of the individual plants sampled. Of these 50, only 9 generated polymorphic bands, including SLYD10, SLYD 29, SLYD 30, SEA 5, SEA 6 and SEA 19, STU 1, STU 2, and SME 2. All polymorphic markers generated two alleles each. SEA 6, SLYD 10, and STU 2 amplified nine loci with a frequency of ≤5% in a single plant from the TTU Quaker Farm and two individual plants from Blackwell. This indicates the presence of rare, informative bands that are unique to only three individuals in the total sample populations. The calculated mean number of effective alleles was 1.18 ± 1.049, whereas the average expected heterozygosity was 0.241 ± 0.027 (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary statistics of markers used for the assessment of genetic diversity in Solanum elaeagnifolium populations from Texas, USA.

a Abbreviations: H e, expectedheterozygosity; N e, number of effective alleles; PIC, polymorphisminformation content; SSR, simple sequence repeat.

The number of alleles that are amplified at a particular marker locus is indicative of the genetic diversity within/between germplasm. The more alleles at a particular marker locus, the higher the level of genetic diversity that can be used to distinguish between related lines (Botstein et al. Reference Botstein, White, Skalnick and Davies1980; Geng et al. Reference Geng, van Klinken, Sosa, Li, Chen and Xu2016). The amount of relative information that can be derived from the utilized markers is dependent on their individual PIC values.

In the current study, PIC values for each of the polymorphic markers ranged from 0.014 (SME 2) to 0.621 (SLYD 29), with an average of 0.245 (Table 3). The calculated mean PIC coincided with the mean H e (0.241) established for the same set of markers (Table 2). PIC value for STU 1 was higher, whereas that for SME 1 was lowed compared with values obtained from genotyping S. elaeagnifolium populations from Australia (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wu, Raman, Lemerle, Stanton and Burrows2012). These results further support the hypothesis of S. elaeagnifolium diversification following multiple introductions of the species in Australia. SEA 5 and SLYD 10 recorded PIC values that were ≥0.40, whereas SLYD 29 recorded the highest PIC of 0.621.

Table 3. Polymorphism information content of DNA markers that amplified polymorphic targets in Solanum elaeagnifolium populations from Texas, USA.a

a H e, expected heterozygosity; PIC, polymorphism information content.

Based on the mean and individual PIC values of the DNA markers used, a high degree of genetic diversity was established within individuals of the different populations. This was supported by results of the AMOVA showing that 74% of the total genetic variation observed was due to differences within individuals of the population studied (Table 4).

Table 4. Analysis of molecular variance comparing genetic variation within and among individuals and among populations from Texas, USA.

Solanum elaeagnifolium propagates clonally as well as by seed production through obligate outcrossing (Hardin et al. Reference Hardin, Doerkson, Herndon, Hobson and Thomas1972). Plants that are derived from allogamous seeds are able to maintain a certain degree of heterozygosity due to the reshuffling of alleles and creation of novel genetic recombinations that occur during cross-pollination. To capture the maximum genetic variation present within and between S. elaeagnifolium populations, we sampled individual plants that were grown from S. elaeagnifolium seeds harvested from mature berries of natural populations of S. elaeagnifolium. The high genetic variation within individuals of populations used in the study, as well as the low values of F IS and F IT (Table 4), which measure inbreeding in an individual relative to a subpopulation and total population, respectively, reflects the nature of S. elaeagnifolium as obligate cross-pollinators. Incidentally, the results of the study also confirm the maintenance of a sexual mode of reproduction in S. elaeagnifolium despite its ability to propagate vegetatively through regenerative stem fragments and buds in the roots.

Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Solanum elaeagnifolium

Based on Jaccard’s coefficient, UPGMA analysis distinctly grouped the S. elaeagnifolium individuals into six clusters: I, II, III, IV, V, and IV (Figure 3). Clusters I, II, and III were composed solely of individuals from the TTU rangeland in Lubbock. Cluster IV consisted of individuals collected from a hunting reserve in Blackwell. Cluster V mostly included individuals from the rangeland in Littlefield, with the addition of one plant (individual 87) from the TTU rangeland in Lubbock. Finally, Cluster VI was an admixture consisting primarily of individuals collected from the Lubbock experimental farm and a few individual plants from rangelands in Littlefield and Lubbock. In general, individual plants coming from the same collection site clustered together, suggesting the possible role of selection pressures that are unique to each collection site in driving the genetic differentiation of individuals from each population.

Figure 3. Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean clustering of Solanum elaeagnifolium populations from three localities in Texas, USA, based on Jaccard’s similarity coefficient. Red broken line indicates genetic similarity threshold for the six major clusters identified. Colors indicate the different collection site where each individual plant was sampled.

Selection pressures at each of the collection sites are driven in part by land use and management practices, and each of these has the potential to produce differential adaptation of S. elaeagnifolium. Rangelands are generally uncultivated lands for animal grazing and browsing. They are characterized by limited water and nutrient availability and low annual production (Havstad et al. Reference Havstad, Peters, Allen-Diaz, Bartolome, Bestelmeyer, Briske, Brown, Brunson, Herrick, Huntsinger, Johnson, Joyce, Pieper, Svejcar, Jiao, Wedin and Fales2009). Hunting reserves, on the other hand, are fenced-in land areas where hunting is carefully controlled. Rangelands and hunting reserves differ in native vegetation, as well as in the degree to which anthropogenic activities impact the composition of flora. Agricultural farmlands are used for the production of crops and are characterized by a high degree of anthropogenic disturbance. Unlike naturally maintained rangelands and hunting reserves, croplands are exposed to a range of conventional management practices, including tillage, irrigation, and agrochemical use (Andreasen et al. Reference Andreasen, Stryhn and Streibig1996; Green and Stowe Reference Green and Stowe1993; Haughton et al. Reference Haughton, Bell, Boatman and Wilcox1999; Kladivko Reference Kladivko2001; Møller Reference Møller2001; Perkins et al. Reference Perkins2000; Rands Reference Rands1986). Intensive agricultural practices such as these have direct impacts on the ecology of croplands, including the existing flora and fauna. More generally, such varied management practices across the collection sites present viable sources of selection pressures that can drive the differential adaptation of species within a given time frame.

The multitude of variable environmental stimuli that are unique to a particular ecology have been shown to serve as barriers that constrict gene flow between populations over time, thus increasing genetic differentiation (Linhart and Grant Reference Linhart and Grant1996). In the present study, the directional selection pressure from both environmental and/or anthropogenic factors that defines each collection site may have caused allele frequency shifts over time and favored specific genotypes with adaptability to each ecology. This hypothesis is supported by the obtained F ST values that estimate the pairwise genetic differentiation of populations (Wright Reference Wright1978). The calculated F ST for the populations ranged from 0.17 to 0.46, indicating high levels of genetic divergence. Differentiation was highest between the Lubbock rangeland and Blackwell hunting reserve, where selection pressures are highly variable, and lowest between the Littlefield rangeland and Lubbock agricultural farm (Table 5). Although selection pressures in rangelands and agricultural farms are different, it should be noted that individuals from the Lubbock rangeland also grouped with individuals from the two former populations to create an admixture.

Table 5. Pairwise genetic differentiation estimate (F ST) matrix for Solanum elaeagnifolium populations from Texas, USA.

a TTU, Texas Tech University.

Several individual plants from the Lubbock rangelands clustered with all the plants collected from the experimental farm. The rangeland and experimental farm in Lubbock are located only 1.5 km apart. Given the proximity of the two sites, movement of S. elaeagnifolium propagules (i.e., seeds, root and stem fragments) from one location to another is probable through natural dispersal or via agricultural practices. This may account for the genetic similarity between individuals from the rangeland and experimental farm.

Intraspecific variations that were observed among individuals of the same cluster are attributed to the nature of S. elaeagnifolium as an obligate outcrosser (Hardin et al. Reference Hardin, Doerkson, Herndon, Hobson and Thomas1972). Cross-pollination facilitates allelic reshuffling that results in novel gene recombinations within the genome. This allows naturally cross-pollinated species to maintain an innate degree of variability. Such genetic variation is important in enhancing the ability of small plant populations to remain viable under fluctuating stresses and novel environmental conditions (Wise et al. Reference Wise, Ranker and Linhart2002). In larger populations, genetic variation can favor rapid genetic adaptation without any major loss in genome-wide variation (Menchari et al. Reference Menchari, Délye and le Corre2007).

Genetic adaptation as facilitated by genetic variation is one of the critical mechanisms underlying the adaptive success of invasive species such as S. elaeagnifolium. Understanding the extent of genetic variation that drives the successful establishment of S. elaeagnifolium under different selection pressures will facilitate the design of an effective strategy for the long-term control of the species. In this study, 78 SSR and indel markers that are transferable to S. elaeagnifolium from S. lycopersicoides were identified and used to genotype S. elaeagnifolium populations from four different localities within the species’ native range in Texas, USA. DNA marker profiling established a high degree of genetic variation among individuals within populations, as well as genetic differentiation of each population in response to the selection pressures that are unique to each collection site. Together, these results indicate the great capacity of S. elaeagnifolium for genetic differentiation and, therefore, adaptation to variable selection pressures in potential ranges outside its natural habitat.

To gain a more accurate assessment of the extent of genetic variation present in S. elaeagnifolium that allowed it to gain widespread geographic distribution, genetic diversity analysis of populations that have successfully adapted and established in environments that are drastically different from that of its native range (i.e., northern U.S. states, areas with less than ideal cold and/or wet conditions) will be necessary. To this end, the development of a core set of S. elaeagnifolium–specific markers that can be used in genetic diversity studies in the species remains an important requirement.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or the commercial or not-for-profit sectors. No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2020.25