INTRODUCTION

(Mis)pronunciations of person names are recurrently heard and discussed in political discourse and established media as a practice to conduct discriminative discourse. In July 2019, a member of the democratic party in the US, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, was calling out a news anchor at Fox News for making fun of her name. This prompted a debate about the pronunciation of person names as related to moral issues in politics in general and issues of (dis)respectful behavior in public discourse in particular (The Guardian; Independent). At another occasion, The Guardian reported that Donald Trump explicitly omitted the first part of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’ name during a rally in North Carolina, as part of a racist discourse. During the run-up to the presidential elections and senate elections in October 2020, then incumbent senator David Perdue was called out for being heard as deliberately mispronouncing the Democratic vice-presidential candidate Kamala Harris’ name during a rally as a racist, tactical move.Footnote 1

Extract (1) is transcribed from MSNBC's reporting of this latter incident, including footage from Perdue's speech.Footnote 2

The news anchor introduces the news of the “backlash” as an issue of “mocking” Kamala Harris’ name (lines 1–3), before playing the footage of David Perdue's speech. Perdue's criticism of the democratic party's latest political proposals is first formulated with reference to Chuck Schumer and Joe Biden (lines 5–6), referring to them with both their first and last names. Perdue then suspends the projected continuation of the criticism and extends the list of responsible people with three more persons, namely Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris, to whom he only refers with their given names (line 6). Instead of continuing the list or going back to the topic, he then suspends his talk and repeats Kamala Harris’ given name thrice (line 7). His initial pronunciation of her name accentuates the second syllable—in difference from the news anchor just before who accentuates the first syllable (compare lines 3 and 6). The first repeat is correctly pronounced, accentuating the first syllable (kamala), whereas the second repeat again accentuates the second syllable (kamala), and the third repeat duplicates the two last syllables (kamala = mala = mala). Perdue then accounts for the repeats by claiming that he “doesn't know” (line 8) while the audience breaks out in cheering (line 9), and the footage ends with Perdue formulating an indifferent stance with the exclamation mark “whatever” (line 10). This is further aggravated by the third repeat where the last syllables are duplicated—which invokes a problem that is distinct from a problem of accentuating syllables. The exclamation mark “whatever” indexing indifference, also stands in contrast to claiming the repeats as having actual difficulties with pursuing a correct pronunciation of the name. The news anchor's subsequent reporting of the reactions includes the descriptions of the episode as due to a “simple mispronunciation” versus produced with “racist overtones” (lines 12–13). The harsh reactions to Perdue's claimed mispronunciation are explainable by the fact that Perdue did produce an adequate pronunciation of Harris’ given name, which makes the repeats hearable as deliberate. Perdue's subsequent claim that he is unknowledgeable about how to pronounce senate colleague Harris’ name (whom he's known for three years), is also hard to believe.

These media reports suggest that people orient to prosodic features of public speech and person reference by names as normatively and politically ordered. Moreover, they suggest that people can be heard as pronouncing person names in such a way that they are recognizably referring to a specific person while deliberately mispronouncing the name. The media reporting in the case of Kamala Harris specifically indicate that members of society claim it to be hearable when mispronunciations are made deliberately—or not.

In this article, I examine (mis)pronunciation of person names during a political party's bi-annual congress, where the public announcement of person names is constitutive of the turn-taking procedure and the succession of public speakers. While problems with speech production is a pervasive phenomenon in talk-in-interaction, this article takes an interest in why and how the participants to this congress orient to emerging issues with pronouncing names in a specific sequential context as accountable and reproachable.

The study of names and their use represents a longstanding topic of interest in philosophy of language and linguistics, addressing issues of meaning and, more specifically, the relationship between names and their referents. Today, research in onomastics encompasses a range of cognate disciplines and comprises work on place names and person names that examines historical but also linguistic, soci(et)al and political aspects of names (Hough Reference Hough2016), including issues of how person and place names relate to ethnicity and structural racism (Bertrand Reference Bertrand2010; Clifton Reference Clifton2013; Nick Reference Nick2019).

Names are also relevant for the situated accomplishment of membership categories and social identities, and thus inherent to the production of social order (Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel1963; Sacks Reference Sacks1972). Examining the use of given names as an interactional resource in specific sequential environments, research in conversation analysis has shown that people use names to establish person reference (Schegloff Reference Schegloff, Gumperz and Hymes1972; Sacks & Schegloff Reference Sacks and Schegloff1979; Heritage Reference Heritage, Stivers and Enfield2007; De Stefani Reference De Stefani2016), but also to manage next-speaker selection (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson Reference Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson1974), to do self-identification (Sacks Reference Sacks and Jefferson1995; Schegloff Reference Schegloff, Stivers and Enfield2007b), to establish disalignment/disaffiliation (Clayman Reference Clayman2010), and to organize collaborative activities (Mondada Reference Mondada, Gardner and Wagner2004). Regarding the situated production of person names, it has also been shown that participants to interaction use and hear pronunciation formats as a way to identify and reflexively establish ethnic categories in the course of social interaction (Day Reference Day1994; Markaki, Merlino, Mondada, & Oloff Reference Markaki, Merlino, Mondada and Oloff2010; Hazel Reference Hazel2015).

Situated within the cognate approaches of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel1967; Schegloff Reference Schegloff, Boden and Zimmerman1991; Sacks Reference Sacks and Jefferson1995), this article contributes to research on stereotypical and political aspects of names, as it examines how participants to a political party's congress in Sweden reflexively establish some names as non-Swedish by way of claiming that the chairpersons’ pronunciation of particular names is being done in a marked way. The study examines situated formulations of (non)normativity as a political phenomenon, and more specifically how the participants’ understanding of incongruencies with respect to situated expectancies (Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel1963; Turowetz & Rawls Reference Turowetz and Rawls2021) relate to procedural aspects of social interaction.

In what follows, I discuss the recorded political congress which is the basis for this study. I then analyze the complaint about name pronunciations which occasioned the interest in working this article out. This is followed by an examination of the organizational phenomenon of next-speaker selection in public and the identified cases where troubles with this procedure emerge, before a concluding discussion of the observations and what we can make of them.

DATA, METHODOLOGY, AND OBJECTIVES

The setting: A political party's congress

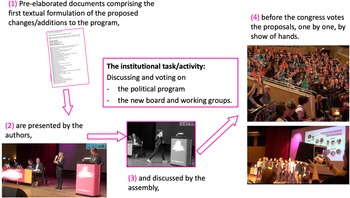

This study emerges from extensive documentation of a political party's congress of a then fast-growing feminist party in Sweden in February 2015. During three days, 400 of the party's members assembled to discuss and modify the party's political program through voting procedures (see Figure 1). The participants to the congress essentially consisted of members of the party who, by virtue of their presence, had the right to vote for or against presented proposals by raise of hands. The proceedings of the congress were made public for members not attending, as well as other interested parties, by means of live-streaming the congress on the internet.

Figure 1. Schematization of the main activities during the congress.

Preparatory to the congress, the attending participants were given access to the proposals submitted by the party's then-current board, proposals submitted by members of the party, and the board's answers/recommendations to the members’ proposals. Apart from additional events, including electing a new board and spokespersons for the party, the principal task of the meeting was to vote for or against the new proposals or proposed changes in the political program.

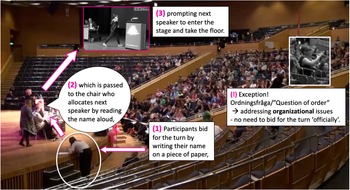

The participants are seated in a large plenum/amphitheater around the stage where the chair, the executive committee, and a sign language interpreter are situated, as well as the podium for the public speakers (see Figure 2). Each proposal is introduced by its author(s), who is given the floor and called on stage by the chair reading the name(s), in the order in which they are indicated in the distributed documents. Subsequent to this presentation, a representative of the party's board is called on stage to present and explain their recommendation to vote for or against the proposal. The floor is then open to the author(s) of a proposal and/or other members of the party to reply to the board and/or to elaborate on the proposals in other ways. To do this, the members of the party could make a bid for the floor via e-mail beforehand, in which case they are already on the ‘speakers’ list’ at the beginning of the proceedings. Attending members, who have not made a bid for the turn beforehand but wish to present arguments for or against proposals to be voted on, can be added to the ‘speakers’ list’ by means of writing their name on a note and forwarding it to the chairperson(s). The order of speakers is thus constituted by the order in which the names of eventual speakers bidding for the turn are acknowledged by the chairpersons by way of writing the names on the list. The public selection of each next speaker is accomplished by the chairperson reading their names out loud. In this way, the turn-taking system is partly formalized in terms of the pre-organized procedure (Drew Reference Drew, Drew and Heritage1992), while the implementation of the order of speakers is progressively established in a situated way, by embodied means.

Figure 2. Schematization of the turn-taking procedure.

The only way to legitimately take the turn without making a formal bid via the ‘speakers’ list’ is formulated as producing a ‘question of order’. A question of order is declared to be admissible at any time, under the condition that it concerns procedural aspects of the meeting such as the need for pauses, the order of the propositions submitted, issues of access to hearing, and so on. The chairpersons have declared that each question of order is to be scrutinized for its relevance as a question of order, and they dismiss it when considered as referring to the political content of the ongoing debate.

Methodological considerations

Adopting an approach to the study of social action within the framework of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, this article attempts to reconstruct the participants’ displayed understanding of the normative order(s) that are reflexively established in and through the interaction. The documentation of the activity includes about twenty hours of audio and video recordings of the political congress running over three days. In addition to the three cameras that were used for the data collection, the audio and video recordings that were produced on behalf of the local organization for live-streaming the congress on the internet were also obtained. The excerpts drawn from the recordings are represented as multimodal transcriptions according to the conventions elaborated by Jefferson (Reference Jefferson and Lerner2004) and Mondada (Reference Mondada2019), which allows for a fine grained, sequential, multimodal analysis of the interaction.

The permission to record the proceedings was requested and granted prior to the congress and the participants were informed and gave their consent to be filmed at the beginning of the congress. One section of the congress hall was allocated to participants who did not want to be recorded, and their contribution to the proceedings are not included in the data.

The analysis has been done on the participants’ original names, while all names are replaced with pseudonyms in this article. Although it poses a problem to present analysis of pronunciations of person names while constraining their representation to pseudonyms, it is of importance to take the participants’ anonymity seriously and in accordance with their given consent. Furthermore, the analysis does not aim to address the names per se, but the way in which their local production is oriented to by the participants in situ.

The choice of alternative names has been made in accordance with the principle of keeping the same number of syllables and similar prosodic features to the largest extent possible. This includes choosing pseudonyms sharing cultural connotations and phonetic features that are relevant for organizational aspects of the interaction, such as names beginning with a consonant/vowel or a fricative/plosive consonant (see Jefferson Reference Jefferson1973 for a discussion).

ADDRESSING POLITICAL ASPECTS OF ORGANIZATIONAL PROCEDURES

In this section we discuss a complaint, in which a participant calls out the chairperson(s) for mispronouncing some names during the previous session(s). The sequence emerges at the very beginning of the third plenary session of the congress, after a coffee pause, as Noma (NOM) takes the turn without first making a formal bid for the turn. She formulates a “question of order”, the legitimacy of which is conditional on that the intervention addresses organizational aspects of the proceedings—as opposed to ‘political’ or content-related issues. As the turn unfolds, Noma produces a criticism of the chairperson(s) (CHA) as she claims that ‘non-normative’, ‘non-Swedish’ person names are pronounced with marked formats.

Noma takes the turn in overlap with the chair person (line 2), who is announcing the next speaker (line 1). She progressively establishes herself as a legitimate speaker (lines 2–7) by formulating the initiated action as a ordningsfråga ‘question of order’ (line 4). In this way, she orients both to the accountability of taking the turn without first bidding for it, and establishes herself being entitled to do so, as well as the initiated action to be legitimate. The cut-off after eller ‘or’ (line 4), and the subsequent restart (line 7), which develops the complaint, also embodies an orientation to a normative issue of adequately formulating the action as not being a ‘question’. In this way, she orients to the institutional context which partly is recognizable in the particular distribution of rights and obligations concerning who can do what actions when.

As Noma raises the issue of the way in which names in the speakers’ lists are pronounced, she retrospectively depicts the prior instances of next-speaker allocation as problematic with regard to just how they have been produced (lines 8–9). Furthermore, she formulates the problem as concerning the claim that the way in which some names are produced treats them as inte är normativa ‘not normative’ (line 10) and further specifies that as not being helt svenskt ‘totally Swedish’ (line 11). Her subsequent re-enactment of the way in which prior announcements have been made, does not only provide an exemplification of ‘Swedish’ and ‘non-Swedish’ names (lines 11–12), but also explicates the way in which the names she refers to as troublesome have been produced (line 12). The first consonant is stretched, like the second syllable, which also is produced with a rising intonation before a short cut off, and ends with a falling intonation on the last syllable of the name. Noma then adds a criticism of the way in which this is treated by the person pronouncing the name, producing a reported speech in first person with an animated voice—aa hoppas att jag inte eh ‘oh hope that i don't eh’—which restates an apologetic wishful expression that does not explicate the actual issue (line 13). The multi-unit turn formulates a stance by stating that she does not think that this particular behavior is okay, thereby providing an account for the intervention (lines 13–14). The assembly responds with applauses (line 17), whereas the chairperson treats the intervention as a criticism (line 16) and makes a prospectively oriented promise to do her best to not do mispronunciations in what follows (line 18).

Noma's intervention depicts the practical issue of announcing next speakers as a political problem for which she holds the chairpersons accountable. In this way, she addresses a deontic aspect of the ongoing activity, which is related to the distribution of responsibilities among the participants. By way of formulating the problem as the pronunciation of certain names, she invokes a situated expectancy regarding how this should be done. In this way, the participants locally construe and ratify ‘correct pronunciation’ and ‘mispronunciation’ of names as relevant categories within the activity. In producing the complaint and explicating the normative order of how to do prosodic realizations of person names and how they relate to national identity and categorization, she displays a member's analysis of what names are normative and that the relevant norm is ‘Swedish’ (cf. Schegloff Reference Schegloff2005). She also manifests that the unfolding talk during the meeting is monitored by virtue of its public and political character. In this way, she retrospectively establishes that how the organizational practice of announcing person names to select next speakers has been done is consequential for what she is doing now, and produces in this way a criticism of that procedure. This is further demonstrated in the negative formulation that reflexively establishes a prospectively oriented expectancy concerning an alternative and acceptable way of how to proceed.

Whereas the reports about the incidents in the context of US politics depicted the mispronunciation of person names as part of a political discourse, Noma's complaint does not declaim a racist discourse as such, but addresses an issue of know-how concerning expectancies of how-to-do-chairing. More specifically, Noma identifies an interactional and procedural phenomenon in this institutional setting as a political problem. Moreover, she does this by explicating (i) a specific action (publicly announcing the name of a next speaker) (ii) in a specific sequential environment (when allocating the floor to a next speaker) (iii) with a specific format (try-marked prosodic features and apologetic elements that are indicative of the announcements as delicate).

Noticing this intervention makes it relevant to ask what prompted Noma to make this particular analysis of the meeting's proceedings and to produce the complaint at this point in time (Sacks & Schegloff Reference Sacks and Schegloff1973; Sacks Reference Sacks and Jefferson1995). By way of referring to and enacting previous announcements of person names, Noma displays an orientation to the local historicity of the public meeting as relevant for what happens next. The complaint, which is ultimately accounted for by the re-enactment of previous announcements, also claims that the previous announcements share distinct formal properties that are recognizable as being (in)congruent with the situated expectancies that all person names would be pronounced in an ‘equal’ way. The explicit orientation to recurrent aspects of the identified practice that Noma refers to and formulates warrants an inspection of what prompted their categorization as noticeably deviant from specific other instances, and how this relates to issues of ethnic categorizations.

PUBLICLY SELECTING THE NEXT SPEAKER(S)

Going through the recordings of the meeting until this point in time resulted in the identification of twenty-one instances of pronunciation of proper names read aloud from emerging lists of speakers bidding for their turn. The result of the case-by-case analysis of these instances shows how the recurrent procedure of announcing next speakers is established as a political problem through and within the situated interaction.

Institutional multi-party interaction engenders specific practical problems for participants selecting next speakers and is often organized as pre-allocated turn-taking systems, such as those observables in court proceedings (Atkinson & Drew Reference Atkinson and Drew1979; Drew Reference Drew, Drew and Heritage1992), mediation and judiciary hearings (Garcia Reference Garcia1991; Raymond, Caldwell, Mikesell, Park, & Williams Reference Raymond, Caldwell, Mikesell, Park and Williams2019), news interviews (Heritage Reference Heritage and van Dijk1985; Greatbatch Reference Greatbatch1988), and political meetings (Mondada Reference Mondada2013). To publicly select and establish next speakers is not only a practical problem of audibility, for example, but an organizational issue intrinsic to the distribution of institutional roles (Atkinson Reference Atkinson, Atkinson and Heritage1984) and the participants’ rights and obligations concerning how to legitimately engage in the institutional activity (Lewellyn Reference Llewellyn2005; Mondada, Svensson, & van Schepen Reference Mondada, Svensson and van Schepen2017; Raymond et al. Reference Raymond, Caldwell, Mikesell, Park and Williams2019).

In the context of this congress, selecting the next public speaker(s) is managed by a chairperson by way of reading the written bids for taking the turn and to announce them in the microphone. This procedure relies on a complex relation between and situated use of the written and the spoken language. The participants treat this procedure as a recognizable and accountable assembly of normatively ordered practices. In this section, we look at three instances where the recurrent formal properties of the locally organized public selection of next speakers are observable.

During this day of the congress, two chairpersons alternate to manage the next-speaker selection. In excerpt (3), the current speaker, Mira, is finishing her turn and the chairperson announces the next speaker, Amelia, on the ‘speakers’ list’, who is standing next to the stage (see image 3a).

As Mira finishes her turn with the concluding ja ‘yes’, she turns her head and looks at the chairperson, orienting to her as the next speaker (line 1, image 3a). The chairperson hears the ja ‘yes’ and the following silence as Mira finishing her turn, as she establishes mutual gaze with her (line 2, image 3b), and then nods and turns to the audience, while Mira walks away from the podium. After looking down at her papers in front of her she gives thanks to Mira and announces the next speaker—då har jag amelia på talarlistan ‘then I have amelia on the speakers’ list’ (lines 3–4). As she announces the name, she looks towards Amelia who is waiting next to the stage and who starts walking to the podium as her name is announced (line 4, image 3c).

In excerpt (4), we also join the interaction as the current speaker, Ragnhild, is closing her turn. The chairperson announces the next speaker, Ann, who already waits on the stage (see image 4a) and continues by announcing the second next public speaker.

As we saw in excerpt (3), the current speaker looks to the chairperson at the end of her turn (line 2, image 4a), which the chairperson treats as marking the end of her intervention by way of looking at her (line 3, image 4b), looking down at the speakers’ list (line 3), and then giving thanks (line 4). He then projects the announcement of the next speaker verbally (line 4), and as soon as the given name is pronounced, Ann starts walking towards the podium (line 5). In this way, she displays that she hears the chairperson selecting her as the next public speaker. The chairperson continues with a prospective formulation of her action as lämna ett anförande ‘leaving a speech’ (lines 5–6, image 4c), which is indicative of the institutional aspect of the setting, and, in difference from excerpt (3), then also announces the second next speaker (lines 6–7).

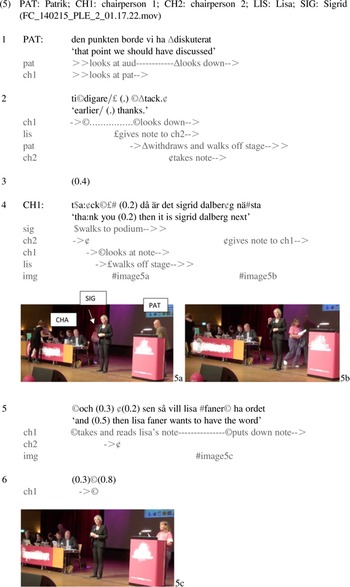

In excerpt (5), the chairperson also announces the next two public speakers and the proceedings are complexified by the fact that a second bid for the turn is forwarded to chairperson 2 (CH2) and handed over to chairperson 1 (CH1), while he announces the next speaker, Sigrid, who already stands on the stage.

The current speaker Patrik finishes his turn by giving thanks and then looks down and moves away from the microphone (lines 1–2), making relevant an eventual announcement of the next speaker. The chairperson orients to this by looking down at his papers and giving thanks (lines 2–3), before announcing the next speaker, Sigrid (line 4). It is noticeable that the next speaker again initiates walking towards the podium before the name has been read aloud (line 4, images 5a, 5b). This is indicative of the meeting's sequence organization, and the specific and publicly recognizable prospective features of its turn-taking system.

During the end of Patrik's turn, another participant, Lisa, leaves a note to the other chairperson (line 2). As CH2 passes the note to CH1, during his reading of Sigrid's name (line 4), CH1 projects the relevance of the note with regard to the list of next speakers with the conjunction och ‘and’ (line 5). In this way, he integrates the passing of the next bid in the unfolding turn through the syntactically fitting increment, and publicly adds Lisa to the speakers’ list (line 5, image 5c).

Excerpts (3), (4), and (5) illustrate a number of recurrent features with regard to the participants’ manifested understanding and situated accomplishment of publicly selecting next speakers within this turn-taking procedure. It is also worth noticing that the ensemble of the participants treats the chairperson as the expected next public speaker at the completion of each ‘public turn’, which also is indicative of the institutionality of the setting.

In this section, we have discussed instances where the chairpersons’ public selection and announcements of the next speakers’ names are produced in a non-problematic way and embedded in a recurrent turn format. Giving thanks, retrospectively establishes the prior speaker's turn as finished and prospectively establishes the relevance of the next speaker to take the floor. This projectable aspect is enhanced by the format of the announcements that are initiated with the temporal formulations då ‘then’, followed by formulations such as “it is X next” and “I have X on the speaker list”. This projectability is ultimately manifested in the observation that the next speakers start moving towards the podium during or before the public announcement of their name(s). This shows that participants who have made a bid for the turn inspect the ongoing interaction for recognizable slots for the announcements of the next speaker(s) to be made. It also shows that what they treat as a relevant next action relies on their situated understanding of contextual contingencies rather than the formal properties of the practice of announcing person names in the microphone. The participants make use of family names, given names, as well as a combination of the two.

Excerpt (5) moreover shows how the order of next speakers emerges and is established in situ, as a possible next speaker bids for the turn during the chairman's announcement of who-speaks-next, which is procedurally consequential for the ongoing activity. This shows that the chairpersons treat it as relevant that this order is transparent for the overhearing audience as well as for next speakers, who monitor when it is their turn and prepare for this by progressively approaching the stage and the podium. The excerpt also renders observable the ordinary aspects of the turn-taking procedures in this setting, including aspects orienting to facilitating participation, which calls for particular organizational features—partly due to its multi-party character (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson Reference Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson1974; Schegloff Reference Schegloff, Have and Psathas1995).

In summary, we have seen that the participants monitor the ongoing activity for particular features that make relevant specific action trajectories at specific points in time, and that this sequential organization of speakers taking turns in public is projectable and implemented as such before it is accomplished through its formulation in-so-many-words. In the next section we look at instances where some problems with pronouncing person names are observable.

EMERGING PROBLEMS WITH PUBLICLY NAMING THE NEXT SPEAKER(S)

In total, twenty-one cases have been identified, where a chairperson selects the next speaker by reading their name(s) out loud up until the moment at which the complaint in excerpt (2) emerges. The two cases analyzed in this section share formal properties that deviate from those that are observable in excerpts (3), (4), and (5), and are candidates for explaining the complaint in excerpt (2). In excerpt (6), the chairperson encounters some problems with pronouncing the names of the next two speakers, which is manifested through hitches, pauses, self-repair, and stretched sounds.

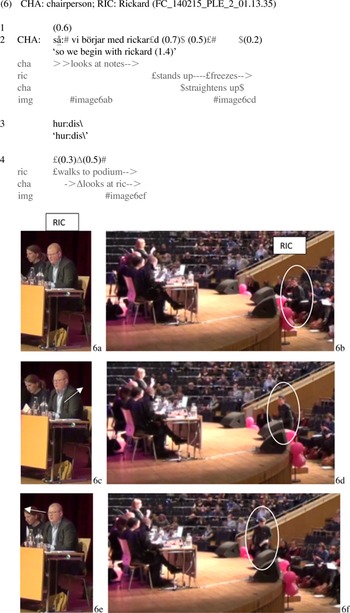

At the beginning of excerpt (6), the chairperson projects the announcement of the next speakers (line 2, images 6a, 6b). As he pronounces the first given name, Rickard in the audience stands up, treating it as addressing himself, and projects to enter the stage as (line 2, images 6c, 6d). However, instead of continuing with announcing the family name, the chairperson sits up in the chair, manifesting an embodied display of trouble and making a long pause (line 2, images 6c, 6d). Rickard hears the announcement of the family name as noticeably missing, as he suspends his initiated trajectory, treating the announcement of the surname as consequential for entering the stage. Only after the chairperson announces “hur:dis\”, with a stretched syllable and falling intonation, making it hearable as try-marked (line 3), does Rickard pursue the trajectory and walks to the podium (line 4). The fact that the chairperson monitors Rickard before proceeding with the next name also suggests a display of some uncertainty regarding the public selection as ‘successful’ in the sense of treated as ‘heard and understandable for all practical purposes’ (line 4, images 6e, 6f). In the continuation of the interaction in excerpt (6), as Rickard is still walking, the chairperson in (7) below proceeds with announcing the speaker after Rickard, with which he also encounters some problems.

After a pause, the chairman projects to continue with announcing the next name on the speaker's list, but cuts off the initiated turn, displaying trouble (line 5, image 7a). After a pause, he then announces the given name with a try-marked reading through a stretched syllable. Moreover, after announcing the first syllable in the family name, he makes another cut-off (line 5), which is followed by a pause (line 6) and another embodied display of difficulty (lines 6–10, image 7b).

While Rickard entered the stage looking in front of him, he now turns to the chairperson and provides the name in a low voice (line 7, image 7b). Importantly, this shows that, at least for Rickard, it is intelligible what name the chairperson attempts to pronounce and that he is familiar with the name. This also makes the candidate pronunciation hearable as a corrective alternative. After another pause (line 8), while keeping his gaze on the written note, the chairperson repeats the name with a try-marked intonation (line 9) and nods twice, while looking to the audience (lines 9 and 10). The fact that the chairperson's conduct prompts some laughter in the audience (line 11) shows that his conduct is observable as retrospectively displaying a self-critical stance towards his own difficulty to pronounce the names. This is further elaborated with the sarcastic smack in response to the laughter (line 12, image 7c) and the subsequent disclaimer (lines 14–15). By way of ‘reserving’ himself concerning ‘all’ pronunciations, he disclaims his responsibility for the trouble and treats it as an involuntary problem of pronunciation in general and not name-specific. In this way, the disclaimer is not only retrospective but it also has a prospective character, alluding to the possibility that it might happen again. The subsequent “thank you” (line 15) explicitly addresses the audience, orienting to the public character of the mistake and its accountability, while closing the sequence.

The pronunciation of person names in excerpts (6) and (7) is distinct from the previous excerpts, which is represented and observable in the transcription. Importantly, this distinctiveness is not only heard but also noticed by the participants, who treats it as deviant and apology-implicative. The next excerpt emerges only one and a half minutes later, as Rickard Hurdis finishes his statement. The chairperson shows to again have difficulties to pronounce the next speaker's name (Deva Javadi) and, moreover, manifests to have the same problem with the name after that (Krister Pernele) on the speakers’ list.

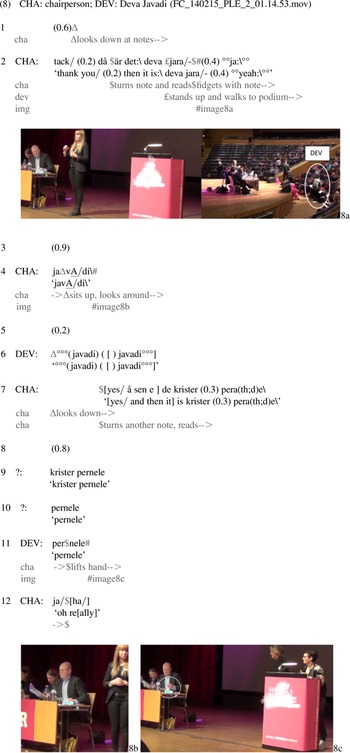

After looking down at the notes and thanking the previous speaker, the chairperson continues with announcing the next public speaker, Deva Javadi (line 2), with a format that is similar to excerpts (3), (4), and (5). However, the empty object det ‘it’ is stretched and produced with a falling intonation, which projects some troubles with announcing the subsequent name. While the given name then is produced in an unproblematic way, the family name is cut off after the second syllable, which is followed by a pause, before the chairperson again manifests the accountability of failing to announce the name through the °°ja:\°° ‘°°yeah:\°°’ (line 2). The low voice, the stretched vowel, the falling intonation and the sequentially peculiar placement of the particle are features that retrospectively orient to the trouble and prospectively display that the chairperson is still engaged in talking, projecting more to come.

As it was noticeable in the other excerpts, Deva Javadi orients to the chairperson announcing her first name as selecting her as the next speaker, as she stands up and starts walking to the stage (line 2, image 8a). After another long pause (line 3), the chair engages in announcing the family name again, with a try-marked format, stressing the second syllable by producing it with a rising intonation and louder voice, while straightening up and looking around (line 4, image 8b; cf. excerpts (6) and (7)). Deva Javadi, who has now approached the chairperson, repeats her own name twice (line 6), which the chairperson responds to with a confirmation token in English: yes (line 7). The language shift and the rising intonation treats the trouble as over-and-done-with (line 5), and by way of omitting to repeat the adequate pronunciation, the chairperson avoids treating Deva Javadi's announcement of her own name as a correction (cf. Jefferson Reference Jefferson, Button and Lee1987; Svensson Reference Svensson2020), but rather as a request for confirmation, which he grants. He then treats the sequence as closed as he continues with announcing the following speaker with a format similar to the other excerpts, å sen e de ‘and then it is’, while reading the next note (line 7).

The following speaker's name also shows to be problematic to announce. Similar to excerpts (6) and (7), the chairperson makes a pause after the given name (Krister) before announcing the family name with a stretched beginning of the last syllable, which is pronounced in a non-articulate manner as it is difficult to distinguish as having the properties of a ‘dental’ /d/ or a /ð/ (like the English ‘th’), and hearable as something like Perathe. It is notable that neither of these phonemes are included in the set of Swedish standard phonemes. After another pause (line 8), several participants correct the announced name to Krister Pernele (line 9) and Pernele (lines 10–11). In this way, they display that the target name is hearable and recognizable although the pronunciation is treated as wrong and established as correctable. The chairperson recognizes the alternative pronunciation as a correction by doing a hand gesture of resignation and verbally aligning with jaha ‘oh really’ (line 12). This change of state token not only acknowledges the correct pronunciation of the name, but also treats it as something that could not have been known and that he is not accountable for (Heritage Reference Heritage, Atkinson and Heritage1984) (lines 11–12, image 8c; cf. excerpt (4)). In the continuation of the previous excerpt in (9) below, we see how the participants further establish the normative aspects of (mis)pronouncing person names in public as an accountable action that is inspectable for its adequacy while being sensitive to local contingencies.

When Deva takes the turn, she provides a candidate explanation for the chairperson's difficulties in announcing the names by way of depicting her own handwriting as the reason for the issue (lines 13–14), and explicitly assuring that there is nothing wrong with the chairperson's pronunciation (lines 14–15, image 9a). However, she continues by repeating her own and her colleague's family names and closes the statement with a formulation of how the names are supposed to be pronounced from then on. Although Deva in this way takes the responsibility for the trouble, the chairperson acts as the recipient of the statement and acknowledges the name formulation by making ‘thumbs up’ (line 16, image 9b). Deva's public repetition of the names also displays that the participants treat it as relevant for the activity to assure a correct announcement of speakers.

This situated negotiation of trouble responsibility orients to and reflexively establishes the delicacy of the situation as going beyond eventual organizational issues of (mis)pronouncing person names of next speakers. The observation that the selected next speakers display their understanding of being addressed by way of moving towards the stage and that other participants provide alternative and corrective pronucnications of the names, shows that the issue is heard and treated as a problem of normativity—as opposed to a trouble of intelligibility. This is further indicated by the interactional work that the participants engage in for minimizing the misconduct, that is, claiming to not know better (excerpts (6) and (7)) and blaming it on a problem of writing (excerpts (8) and (9)).

This section has discussed the two identified instances where the pronunciation of person names in the sequential environment where next speakers are announced is treated as problematic by the chairperson, by the selected next speaker, and by the other attending and overhearing participants. The multimodal transcription allows us to describe and point out a number of characteristics that account for their distinctiveness with reference to the nineteen non-problematic formats, of which three were discussed in excerpts (3), (4), and (5). These include stretched vowels, cut-offs, pauses, restarts, changing postures, suspended movements, and facial expressions. The sequential analysis shows that the pronunciation of person names, in terms of their situated production, is consequential for the sequence organization with regard to the public turn allocation and announcement of next speakers. The hesitations and subsequent corrective alternatives indicate that the participants monitor their own and others’ speech as inspectable for its accordance with normative orders of prosodic formats. These observations are interesting in their own right. Moreover, they explicate at least some of the local historicity and contingencies of the congress as implicative for the emerging question of order and statement of dissatisfaction that was observed in Noma's complaint in excerpt (2).

DISCUSSION

This article has discussed the noticeable features of pronouncing person names as a politically sensitive matter. The organizational issue of next-speaker-selection in this setting, as it constitutes a practical problem of rendering ‘who's next’ publicly available, is embedded in the embodied practice of reading names out loud. The participants orient to the pronunciation of person names when they are publicly announced as related to norms of ‘ordinary’ vs. ‘strange’ names—norms of ordinary vs. try-marked prosodic realization of person names and norms regarding the participants’ right to be correctly introduced when speaking in public. The sequential micro-analysis of how the names are announced indicate that the participants orient to recurrent phonetic patterns that are indicative of a normative order regarding how (not) to pronounce person names. The participants treat these announcements as a category-bound activity (Sacks Reference Sacks1972) and their prosodic realization as an accountable action. This converges with and elaborates on prior research about the interactional and political aspect of ‘procedural work’ that is attributed to institutional roles.

In excerpt (2), we observed that Noma formulates a complaint related to the procedural aspects of how ‘non-Swedish’ names were pronounced. This demonstrates that people hear ways of talking as doing references related to ethnicity. The analysis of excerpts (3), (4), and (5) showed how the participants to the congress organize taking-turns-at-talk by means of bidding for the turn by writing down their names and then being selected through the chairpersons publicly announcing the next speaker(s). The analysis of excerpts (6), (7), (8), and (9) discussed the identified instances where some problems with pronouncing names emerges. Moreover, the analysis showed that the participants treat the practice of reading names out loud as accountable, and treat the departure from the normative order of how to accomplish the announcements as apology-implicative. This demonstrates that prosodic features of conversational practices are sequentially implicative. Furthermore, Noma's reenactment of the chairpersons’ prosodic realizations, including stretched syllables, cut-offs, and rising intonation on specific syllables are comparable with the previous problematic announcements of names (cf. excerpt (5), lines 5, 6, 10; excerpt (6), lines 2, 4; and excerpt (7), line 7). This shows that speech is not only monitored for its prosodic features with reference to its local intelligibility, but also reportable as moral issues in latter interaction(s)—even after the end of that session.

The question of order that Noma raises, explicitly addresses the normative order as such, furthermore proposes a reason(ing) for the departure from this norm: that the names are non-standard. Moreover, she relates that deviance to the ethnic category ‘(non-)Swedish’. In this way, the emerging problem with pronouncing the name is established as twofold: the marked pronunciation is heard as attributing categorial features to its bearer and this, in turn, prompts the participant to attribute categorial features of ignorance to the chairperson(s).

As one of the reviewers pointed out, research within the field of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis has looked at prosodic features of talk-in-interaction as procedurally consequential for the interaction and more specifically for issues of membership categorization (Egbert Reference Egbert1997, Reference Egbert2004; Bolden Reference Bolden2014; Raymond Reference Raymond2018). In this body of work, it is notable how category work is accomplished through repair sequences orienting to prosodic features of talk. Repair practices are used for doing various interactional work in institutional and political settings by way of claiming and restoring issues of intersubjectivity (Svensson Reference Svensson2020). Participants to the sequences analyzed in this article clearly treat the mispronunciations as an issue of acceptability for ‘all political purposes’—in comparison to claiming issues of intelligibility for ‘all practical purposes’.

This article shows that people not only orient to claims of ‘deliberate’ mis-speaking as (politically) immoral, but also that ‘actual’ mis-speaking is normatively deviant and accountable in some situations. This addresses the issue of how person names and more specifically their local production is heard as being related to membership categories and the situated construction of social identities (Sacks Reference Sacks1979; Jefferson Reference Jefferson, Button and Lee1987). It also addresses the epistemological problem of how to make an empirical analysis of such instances as being an issue of ‘non-normative’ names without making an a priori assumption of what is ‘normative’ (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007a).

By way of engaging in a sequential analysis of naturalistic data that are documented for research purposes, interactional and political norms can be revealed and discussed in their own right. The seen, but unnoticed, aspects of the normative order(s) according to which people organize their activities as and within institutions become demonstrable as participants orient to their features as noticeable features. This study also shows that people orient to the local historicity of an interaction and that participants to interaction indeed do not only scrutinize unfolding courses of action for their relevance with regard to (aspects of) immediate prior and next actions, but scrutinize prior actions for if and how they relate to ‘more’ prior actions and if they eventually are projectable as establishing sense-making (political) norms over time. Finally, it demonstrates that incongruencies regarding the situated expectancies concerning political delicacies are procedurally consequential for the ongoing activity, as it is talked into being.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

Based on conventions developed by Jefferson (Reference Jefferson and Lerner2004) and Mondada (Reference Mondada2019).

- (hein)

ambiguous hearing

- ((abc))

transcriber's comments

- &

turn continuation by the same speaker in/from a next/previous line

- [hein]

overlapping speech

- =

latching (no gap) between turns

- (0.6)

silences in tenths of seconds

- (.)

micro pause less than 0.2 seconds

- -

cut-off sound

- : ::

stretched sound (multiplied with the length in approximate tenths of seconds)

- hein

emphatic stress

- HEIN

higher volume than surrounding speech

- °hein°

lower volume than surrounding speech (multiplied with perceived decrease in volume)

- >hein<

faster pace than surrounding speech

- <hein>

slower pace than surrounding speech

- / \

just-prior syllable was produced with rising or falling intonation

- .tsk

lip or tongue smack

- .h

audible inhalation

- ()

inaudible speech

- <(((2.0) phen)) >

phenomenon for the duration of the indicated time

- grey font

visible phenomena (not numbered lines). The transcription of visible phenomenon does not code embodied features. It describes relevant practices that participants use in concert with vocal and linguistic resources to format social action.

- car

participant doing the embodied action is identified in small caps in the margin

- * *

Descriptions of each participants’ visible, embodied actions are delimited between two identical symbols that are aligned with correspondent indications in stretches of audible phenomena (talk or silences)

- Δ-->

action continues across subsequent lines until the same symbol is

- ->Δ

reached

- >>

action begins before the excerpt's beginning

- -->>

action continues after the excerpt's end

- …

action's preparation

- ---

action's apex is reached and maintained

- ,,,

action's retraction

- img

image; screenshot

- #

exact moment at which a screenshot has been taken