In conventional accounts of Britain’s empire overseas, the eighteenth-century ‘revolution’ in Bengal looms large. The story has been told and retold over the centuries, but the basic elements remain the same: the death of British captives confined in the much-mythologized ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’; Robert Clive’s 1757 victory over the nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey; the definitive confrontation with the combined forces of Bengal, Awadh, and the Mughal emperor at Buxar in 1764; and the East India Company’s assumption of the diwani in 1765.Footnote 1 The Mughal office of diwan conferred the right to collect taxes in what was formerly one of the richest provinces of the Mughal empire; this extensive revenue base is traditionally depicted as the launching pad for Britain’s ‘second empire’ of conquest and exploitation.Footnote 2 The nawab retained nominal control over law and order within the province to begin with, and revenue collection was initially delegated to Indian deputies; in the end, however, this system of ‘double government’ proved short-lived.Footnote 3 By 1772, the Company had assumed formal control, claiming jurisdiction over a non-European, non-Christian population numbering into the millions.Footnote 4 As a result, generations of historians have looked to Bengal to detect the origins of the ideological and administrative mechanisms that would underpin the nineteenth-century empire on which the sun never set. According to one recent study, Bengal was the crucible wherein a ‘new kind of imperialism’ was forged, characterized by ‘authoritarian government, territorial conquest, and extractive revenue polices’, with an ‘emphasis on direct coercion and overt domination’.Footnote 5 Yet, fixating on Bengal obscures other, more pervasive and persistent forms of imperial power. The focus of this book is on the more nebulous, yet no less significant, history of British political influence beyond the borders of British India.

This history parallels, and indeed underpins, the more widely studied story of the Company’s expanding territorial dominions. Just as the Company was working out how to defend and administer Bengal, a distinct yet complementary kind of empire was emerging in parallel. Nawab Vizier Shuja ud-Daula was also defeated at Buxar, but the consequences, for him, were very different. Rather than overturning Shuja’s administration, the Company instead signed a treaty with him, one that guaranteed his independence but required him to pay subsidies in exchange for military protection. Over time, a network of similar agreements known as subsidiary alliances (for the payment of subsidies) began to take shape, founded on terms that were increasingly unequal, and overseen by Company representatives (called Residents) who intervened in the politics of nominally independent kingdoms with increasing audacity. The treaty concluded with the nizam of Hyderabad in 1800 marked a turning point in this process by placing key restrictions on the nizam’s sovereign powers, requiring him to submit disputes with neighbouring polities to the arbitration of the Company and limiting his ability even to communicate with other courts except with the approval of the Resident.Footnote 6 These alliances were designed to obstruct the formation of hostile coalitions and finance the Company’s armies at the expense of their allies’ military establishments. They became the preferred mechanism for subordinating the Company’s Indian rivals, and the basis for the Company’s political and military dominance in the subcontinent. Despite a series of annexations in the mid-nineteenth century, the bulk of these alliances would persist until Indian independence. By this point, allied kingdoms, known as ‘princely states’, numbered into the hundreds and comprised almost a third of the Indian subcontinent and a quarter of its population.Footnote 7

The subsidiary alliance system as it developed in India set an example that reverberated across Asia, Africa, and the Indian Ocean world. Whether rejected, modified, or imported wholesale, this model was an important point of reference as Britain’s global entanglements increased and intensified across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Bengal has been described as ‘the main laboratory for the development of new conceptions of empire’ but this is only the case if we restrict our vision to a narrow definition of empire as direct rule.Footnote 8 As Ann Stoler has argued, by focusing on clearly bounded territories historians of empire have downplayed political and territorial ambiguity as defining features of modern imperial intervention. For Stoler, ‘the legal and political fuzziness of dependencies, trusteeships, protectorates, and unincorporated territories were all part of the deep grammar of partially restricted rights in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century imperial world.’Footnote 9 From the vantage point of the northern Nigerian emirates, the Malay kingdoms, and the Gulf states, nominally independent but subject to Britain’s overweening influence, the princes form a more meaningful precedent.

Despite having developed into a burgeoning field of study in their own right, the princely states rarely feature prominently in recent scholarship on the East India Company.Footnote 10 The reason has to do both with conventional narratives about the Company’s development and assumptions about its essential characteristics. Percival Spear once summarized the Company’s trajectory over the eighteenth century as ‘from trade to empire, from embassies to administration’, and, while Philip Stern has influentially refuted the first half of this formulation, the second continues to inform most scholarship on the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Company.Footnote 11 Historians of the period have tended to study the Company’s expanding bureaucracy. Robert Travers has attributed this trend to ‘the strong historical association of European imperialism with modernity, and the concomitant sense of modernizing European ideologies confronting non-European “tradition”’.Footnote 12 The subsidiary alliance system has become something of a blind spot within this literature, failing in many ways to conform to the pattern of bureaucratization, standardization, and reform usually associated with the early nineteenth-century East India Company.Footnote 13

When the Company’s alliances are placed at centre stage, however, its empire in India starts to look very different. Existing scholarship usually depicts the early nineteenth century as an era of hardening racial hierarchies, wherein a reformed civil service valued abstract and institutionalized ‘facts’ over local, patrimonial knowledge.Footnote 14 At Indian royal courts, however, this ideal proved difficult, if not impossible, to translate into practice; after all, Residents were theoretically supposed to be working through existing structures rather than introducing new ones. Residents, then, had no choice but to accommodate themselves to the world of the court in ways that are more usually associated with the Company’s early history as a supplicant to the Mughals than with this period of accelerated expansion.Footnote 15

Because of the compromises that Residents were sometimes forced to make, Residencies are a revealing lens through which to examine the development of ideas and practices of empire as the Company emerged as paramount power. The Residency system might have survived and indeed been propagated across the Indian Ocean world, but its longevity belies the consistent problems to which it was subject, and the ideological conundrums that it posed. The disagreements that repeatedly flared up around it not only expose divisions within the Company that might otherwise have remained obscure but show how this period of experimentation and debate created opportunities for historical actors to try to bend these emergent systems to their will.Footnote 16

To bring this process of experimentation into focus, this book centres on the changing relationships between the East India Company and allied Indian kingdoms during a period of intensive imperial expansion from 1798 to 1818, concentrating on the Company’s most politically important contacts with Awadh, Hyderabad, Delhi, Travancore, and the Maratha polities of Nagpur, Pune, and Gwalior. This was a time when many of the Company’s most important alliances were concluded, but their long-term implications were only starting to become clear. In retrospect, relationships of ‘protection’ and coercion would become a distinctive attribute of the modern British empire, but at the turn of the century, the future role of indirect rule in cementing British global predominance was not so evident.Footnote 17 The Indian alliance system is usually portrayed as an obvious measure designed to finance the Company’s armies and create a defensive buffer around Bengal. This book, by contrast, argues that the formation of the Company’s empire of influence is a story of debate, resistance, and uncertainty, as colonial officials questioned the feasibility of controlling purportedly independent kingdoms, and the appropriate methods to be employed for this purpose. These tactics were conditioned, enabled, and resisted by the activities of Indians with varying interests and allegiances of their own. Far from being a simple political and military expedient, the subsidiary alliance system was a complex social, cultural, and intellectual enterprise, difficult to justify as well as to implement.

These problems are best appreciated through the eyes of the Residents, the men appointed to represent the Company at Indian royal courts. These were men who, in the words of their leading historian Michael Fisher, stood ‘at the cutting edge of British expansion’.Footnote 18 They were the ‘central yet slender thread that bound the Indian states to the British Government of India’, individuals who powerfully shaped the developing relationships between the East India Company and what would come to be called the princely states.Footnote 19 As such, the Residents found themselves at the centre of heated controversies about how the alliance system should operate, and what their own role and function at Indian courts should be. Focusing on the routine activities of Residency life, this book shows how the Residents navigated the conflicting pressures of court and Company, negotiating between political ideals and imperfect realities to build an empire of influence in India.

This empire of influence, though it overlapped with and underpinned the Company’s territorial dominion in the subcontinent, also possessed distinct features. Whereas in British India, control was exercised through the Company’s administrative and legislative apparatus, in allied states the mechanism of control was, primarily, advice. The goal was to create conditions in which this advice could not be ignored or gainsaid. In some cases, as in Awadh, the right to dispense advice was guaranteed by treaty (to be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 1). In practice, however, much depended on the Resident’s ability to perform his authority convincingly. He had to act the part of someone with local as well as institutional support, someone with information, with resources, someone capable of following through on a threat if necessary. A lot depended, in short, on the Resident. In what follows, I will provide a brief account of who the Residents were and the conditions in which they lived and worked, before describing in greater detail their place within scholarly debates around the nature of empire and indirect rule.

I.1 Introducing the Residents

The potential problems of the Residency as an institution were anticipated by Company executives from the outset. Indian precedents existed, and in many ways formed the foundations upon which the Residency system was built; the role of early Residents as mediators and information gatherers paralleled that of vakils, the agents dispatched by Indian rulers to foreign courts.Footnote 20 Yet, the appointment of diplomatic representatives to act on the Company’s behalf also raised all kinds of questions, including who would nominate and control them, and whether they might not create unnecessary expense and undesirable political entanglements.Footnote 21 The choice of designation for these officials reflects the minimal role that was originally envisaged for them. A ‘resident’ was a relatively humble and low-ranking officer within the European diplomatic hierarchy. The title reflected both the Company’s status as a chartered corporation, and the determination of the directors (ultimately futile, as Chapter 4 will demonstrate) to sidestep questions of precedence and minimize the cost of ceremonial.Footnote 22

The composition of this political line, as contemporaries termed it, fluctuated significantly over time. Military officers, being more numerous and cheaper to employ, initially dominated the service; many early Residents were soldiers who studied Indian languages while in the army.Footnote 23 With the foundation of staff training colleges at the turn of the nineteenth century, the preference shifted towards college-educated civilians instructed in mathematics, natural philosophy, law, history, political economy, and the classics, as well as Indian languages, history, and culture.Footnote 24 Retrenchment in the 1820s cut this trend short; thereafter, Residents were once again more likely to be military officers. While C. A. Bayly and Douglas Peers have hypothesized that this military presence might have created a militaristic culture within the political line, it is worth noting that even though civilians predominated during the period under study, militarism prevailed, for reasons that will be explored in Chapter 3.Footnote 25 Regardless of their professional background, Residents usually belonged to the aristocracy or landed gentry, and were often connected to figures of influence within the Company. They leveraged these ties to secure appointments, usually starting out as secretaries or assistants and then working their way up the corporate ladder as vacancies emerged.Footnote 26

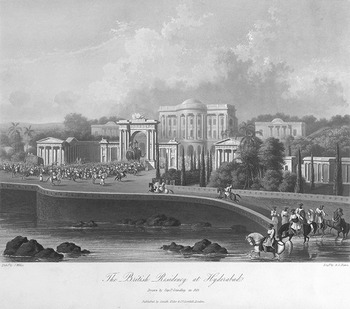

Early Residents lived in houses furnished for them by the courts to which they were posted, but with time began to leave their imprint on the built environment of the cities in which they lived. At Delhi, Residents David Ochterlony (1803–1806), Archibald Seton (1806–1811), and Charles Theophilus Metcalfe (1811–1818) resided in a converted pavilion that had previously formed part of a palace belonging to the seventeenth-century Mughal prince Dara Shukoh.Footnote 27 This building was adapted and enlarged to suit British tastes, with the addition of a colonnaded portico and Ionic columns to costume the pre-existing Mughal structure in Classical garb.Footnote 28 At Lucknow and Hyderabad, grandiose Classical buildings were constructed to house the Resident and his guests, with room for hosting dinners, balls, and other entertainments for army officers, European travellers, and courtly elites (see Figures I.1 and I.2).Footnote 29 Not all Residencies were quite so ornate; at Pune, the Residency compound consisted of a scattering of bungalows far less impressive to the eye.Footnote 30 However large or small, the main Residency building was usually surrounded by smaller offices and houses for the accommodation of its European staff, as well as gardens for their relaxation and enjoyment. Maria Sykes (whose husband was an officer in the subsidiary force stationed at Pune) observed in 1813 that the Residency compound was placed ‘in most delightful pleasure grounds, where the apple and the pear, the peach and the orange, and almond and fig trees overshadow the strawberry beds and are hedged in by the rose, the myrtle, and the jasmine.’Footnote 31 Despite its humble architecture, the Pune Residency occupied a beautiful spot at the junction of two rivers, a setting much admired by European visitors who took advantage of the Residents’ hospitality (Figure I.3).

Figure I.1 Sita Ram, ‘The Residency building in Lucknow’ (1814), British Library, London, Add. Or. 4761, no. 4761.

Figure I.2 Robert Melville Grindlay, ‘The British Residency at Hyderabad, drawn in 1813’ (1830), British Library, London, X400 (19), no. 19.

Figure I.3 Henry Salt, ‘Poonah’ (1809), British Library, London, X123(13), no. 13

As sites of sociability and consumption as well as statecraft, Residencies became important urban centres. At Hyderabad and Lucknow, bazaars (or marketplaces) sprung up to service them and the small population of non-official European residents (mostly traders and shopkeepers) flocked to the neighbourhood.Footnote 32 These spaces surrounding the Residency and associated military cantonments, and the people who inhabited them, fell under the jurisdiction of the Resident. As Michael Fisher has argued, by exempting Europeans and Indian dependents of the Residency from a ruler’s judicial authority, extraterritoriality provided an important mechanism whereby the Resident established his own influence within the city, though, as an incident discussed in Chapter 3 will show, Company executives remained uncertain how far Residents should exercise these powers to punish offenders.Footnote 33

The number of resident European officials varied from place to place. Most Residents were joined by two or three assistants, a postmaster, an officer heading the military escort, and a surgeon.Footnote 34 The number of assistants depended on the relative importance of the Residency in question; the Resident at Delhi, whose purview extended to Rajasthan, Punjab, and Afghanistan, had as many as eight assistants to fulfil a range of tasks, some more judicial and administrative than diplomatic.Footnote 35 Residents were permitted to recommend or consult on prospective candidates for these positions, meaning that the members of his household were often connected to him through ties of friendship, kinship, or patronage.Footnote 36 Sometimes these ties were close. At Hyderabad, William Kirkpatrick (Resident 1794–1797) was assisted by his younger brother James Achilles Kirkpatrick (himself Resident at Hyderabad 1798–1805); just over ten years later Henry Russell (Resident 1810–1820) was assisted by his younger brother Charles.

This small circle of European men depended on a far larger number of Indian employees. By 1817, a typical office establishment included a head munshi (the focus of Chapter 5), up to three writers or copying clerks, sometimes a treasurer, and as many as forty further unspecified ‘natives’ fulfilling a range of tasks.Footnote 37 Added to this would have been the many table attendants, cooks, water carriers, tailors, washermen, grooms, gardeners, porters, watchmen and other staff without whom the Resident’s elite lifestyle would have been impossible.Footnote 38

Some of the Residents discussed in this book cohabited with Indian women, but, with the notable exception of James Achilles Kirkpatrick (whose marriage to Khair un-Nissa earned him Governor General Richard Wellesley’s official disapprobation), these relationships rarely feature in their correspondence.Footnote 39 It is difficult to judge how they may have affected dynamics at court. The status and identities of these women remain, for the most part, obscure. Those whose personal histories are known did not have roots within the courts where the Residents were posted, though they may still have had networks of their own, and likely had useful knowledge to impart.Footnote 40 By forming a relationship with a well-connected woman of high status at Hyderabad, James Achilles Kirkpatrick once again appears to be the exception that proves the rule.

Very few Residents during this period had European wives while in office. Those who did are Henry Russell, who married a French Catholic resident of Hyderabad, Clotilde Mottet, in 1816, and Richard Jenkins, who married Elizabeth Helen Spottiswoode, the daughter of a Company man, in 1824.Footnote 41 Thomas Sydenham was briefly joined at Hyderabad by his sister, Mary Anne Orr (an officer’s wife), from 1808; Elphinstone reported that the two played Italian and Scotch airs on the flute and piano forte for five hours out of the day.Footnote 42 Apart from the occasional visitor and the officers’ wives living in military cantonments, the Residencies were homosocial spaces. In their letters and journals, Residents report hunting, playing billiards, and reading aloud or studying with the male members of their household.Footnote 43

Business hours were mostly spent reading and writing correspondence, interspersed with frequent consultations with ministers and occasional attendance at court levees (depending on the Resident’s preferences). The Maratha courts usually appointed a minister to handle Residency business, while at Lucknow and Hyderabad the Resident interacted primarily with the chief minister. Consultations might occur within the palace precincts, at the Residency, or in the minister’s own abode. In some cases, these relationships could become close; at Hyderabad, Henry Russell and his household frequently visited minister Chandu Lal’s gardens, eating, drinking, and occasionally staying late into the night.Footnote 44

Within the Company, the Residents’ most important point of contact was the governor general or his secretaries, based in Calcutta. In the eighteenth century, the governments of Bombay, Bengal, and Madras had competed for control over the Residencies, but by the turn of the nineteenth century, Bengal had established its authority over key members of the political line.Footnote 45 It was to the governor general that the Residents studied here made their reports, and it was he or one of his secretaries who issued their instructions. It was the governor-general-in-council, in turn, who relayed the Residents’ reports to the Company’s Court of Directors and the parliamentary Board of Control in London. In addition to their official and demi-official exchanges with the governor general, Residents regularly corresponded with one another, partly out of necessity (they were responsible for keeping one another apprised of developments at their respective courts) but also because of feelings of personal and professional affinity, as Chapter 2 will show.

This official and unofficial correspondence, read alongside the Residents’ personal letters and papers, reveals a world in flux. Focusing on an important but understudied period in the history of indirect rule, this book uses the papers and correspondence of the Residents to understand how they tried to consolidate control despite resistance and unrest at court, and ideological division within the Company. In the process, characteristic narratives about the foundations of Britain’s nineteenth-century empire, and the logic behind emergent strategies of indirect rule, begin to seem less certain.

I.2 Diving below the Waterline

Over half a century ago, two historians influentially pushed the boundaries of how the British ‘empire’ was defined. Criticizing their contemporaries for fixating on ‘those colonies coloured red on the map’, John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson memorably suggested that equating British overseas expansion with formal empire was ‘rather like judging the size and character of icebergs solely from the parts above the water-line’.Footnote 46 This provocation generated decades of debate around the usefulness and validity of the concept of informal empire, particularly its application to Latin America.Footnote 47 Though contentious, these exchanges have been intellectually productive. Robinson and Gallagher encouraged British historians to look below the waterline (to borrow their famous metaphor) and see dominion as forming part of a wider repertoire of strategies for the pursuit of economic and political gain overseas. Key among these strategies was indirect rule.

Usually defined in opposition to direct administrative control, indirect rule encompasses various forms of imperial oversight. For the purposes of conceptual clarity, political scientists Adnan Naseemullah and Paul Staniland have identified three types: suzerain governance (whereby the princely or tribal state remains nominally independent and internally sovereign but recognizes the overarching authority of the imperial power); hybrid governance (whereby the imperial power and indigenous ruler share authority which they exercise in distinct but overlapping spheres); and de jure governance (where the imperial power has legal and administrative authority over the territory in question, but that control is enforced locally by intermediary political elites and strongmen).Footnote 48 These types, though implemented differently, are nevertheless founded on the same basic premise, namely, the desirability of working through existing institutions. All three are also calculated to fulfil the same essential purpose, that is, control. For Michael Fisher, this ‘determinative and exclusive political control’, recognized by both sides, is the defining feature of indirect rule.Footnote 49 The Residency system during this period largely conformed to what Naseemullah and Staniland describe as ‘suzerain governance’, with the Company controlling their allies’ foreign policy while leaving their internal administration largely intact. Indirect rule was not a term used during the early nineteenth century, when colonial officials tended to speak in terms of ‘influence’, ‘interference’, ‘connections’, and, increasingly, ‘ascendancy’ or ‘paramountcy’.Footnote 50 Still, as an analytical category indirect rule helps to remind us of broader patterns in the logic of colonial rule, encouraging us to address the big questions about why empires develop in the way that they do, and how they bend existing structures to their needs. In particular, studying indirect rule encourages us to think about power: what it is, how it is exercised, and the different forms it can take, some of which are less apparent than others.

This book is unusual in its chronological focus, since indirect rule is usually described as a late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century phenomenon. As a philosophy of rule, it is conventionally associated with Frederick Lugard and his book The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (1922), widely considered the most influential statement of indirect rule’s theoretical underpinnings and practical advantages.Footnote 51 Lugard’s book marked the culmination of a late nineteenth-century process whereby indirect rule was implemented across the African continent as well as in Southeast Asia, Fiji, and the Persian Gulf. Two justifications have been advanced to explain its popularity. First, that it represented a means of bypassing the problem of resources at a time when the colonial state had limited funds and few staff, enabling what Sara Berry has described as ‘hegemony on a shoestring’.Footnote 52 Second, that it was born out of the crises of the mid-nineteenth century, when experiences of the 1857 Indian Uprising convinced officials of the fundamental otherness of their colonial subjects, and the concomitant need to set empire on a firmer footing by grafting it onto pre-existing political and social structures.Footnote 53 Despite their different emphases, both explanations posit indirect rule as an alternative developed in response to the burdens and complications posed by direct rule.

The place of the early Residencies within this narrative is unclear. Given its establishment in the late eighteenth century, the context in which this system took shape was evidently different. Usually, the pragmatic justification is preferred as an explanation for its emergence. Scholarly convention holds that the Company’s increased intervention into the politics of allied kingdoms was propelled by the need to ensure the smooth flow of subsidies to finance their armies. According to this argument, an aggressive form of indirect rule was foretold almost from the beginning.Footnote 54 The continued existence of these nominally independent kingdoms is viewed as a pragmatic measure on the part of the Company because of the almost self-evident benefits that indirect rule was seen to confer: that it was inexpensive; that it was practically effective; and that it was less likely to inspire Indian resistance.Footnote 55

Because the development of the Residency system is usually portrayed as common-sensical and ad hoc, the cultural and ideological frameworks that informed its early evolution remain largely unexamined, the assumption being that there is little of interest to recover here. By contrast, the late nineteenth century has begun to attract historians interested in piecing together the theory of indirect rule and the status of the princely states within international law. These legal and intellectual historians have been enticed, no doubt, by the voluminous manuals and reports compiled by legal theorists and employees of the Foreign Office during this period. Based on this printed evidence, both Karuna Mantena and Lauren Benton locate the origins of a theory of indirect rule in India in the late nineteenth century, focusing on thick tomes authored by Henry Sumner Maine and Charles Lewis Tupper, respectively.Footnote 56 In so doing, the earlier history of these relationships is elided. The whole story is summarized in a sentence by Benton as a process whereby ‘the princely states were quickly and clearly made subordinate to the British.’Footnote 57 There is little attention to the ideas and assumptions underpinning the early Residency system, ideas that were largely implicit and constructed through experimentation and negotiation on the ground rather than elaborated in texts and treaties.

Disinterest in the early nineteenth century can also be explained in part by the almost magnetic effect of the 1857 Uprising. Traditional views of Indian rulers as pillars of imperial power during and after the rebellion have prompted historians to demonstrate the extent to which rulers continued to exercise political agency within their own domains, even at the height of the British Raj.Footnote 58 Recent examples that emphasize princely autonomy during this period include Manu Bhagavan’s account of educational reforms in Baroda and Mysore and Eric Lewis Beverley’s study of Hyderabad’s connections with the Muslim world.Footnote 59 These analyses have revised our understanding of politics in the Indian princely states, incorporating them into wider debates in Indian and world history. Still, they are more concerned with recovering the agency of princes ruling under conditions of apparent thraldom than with understanding the process whereby the subsidiary alliance first took shape.

Historians who have addressed indirect rule’s eighteenth-century origins have tended to adopt a regional focus.Footnote 60 As a leading power within the fragmenting Mughal empire and the first court to be connected with the Company through a subsidiary alliance, Awadh has generated the most interest.Footnote 61 Richard B. Barnett’s North India Between Empires: Awadh, the Mughals, and the British 1720–1801(1980) is a classic of the genre. In adopting this lens, South Asianists have produced detailed case studies documenting the changing configurations of power at individual courts. Yet, this approach fails to capture the development of a Residency system defined by the movement of people and ideas between places.

The synthetic studies by Michael Fisher and Barbara Ramusack most closely approximate the analysis undertaken here. Fisher’s classic account provides a complete history of indirect rule within the Company, from 1764 to its abolition in 1858. Ramusack goes even further, tracing the history of the Residencies from their origins to independence in 1947. Both are impressive and widely cited works of scholarship that continue to dominate the field. Yet, both are also comprehensive overviews which, because of their broad coverage, necessarily do not furnish intimate details about what life at the Residency was like during any given period. These are political and administrative histories concerned with tracing institutional trends at the expense of details that do not fit. Whereas Fisher and Ramusack provide invaluable narratives chronicling change over the longue durée, this book casts a spotlight on a formative moment in the history of the Residency system, illuminating some of the messiness and uncertainty that might otherwise fade from view.

A key advantage of this roughly synchronic approach is that in narrowing the chronological scope, the emphasis shifts from big events to mundane realities. Empire of Influence is, above all, a cultural history concerned with the ideas and practices that constituted the day-to-day life of indirect rule during this experimental stage. By elucidating the conceptual frameworks within which the Residents interpreted events in the subcontinent, we can better understand the rules of political behaviour that they set for themselves. Delving into the details of day-to-day life permits us to see how and why these intentions did, or did not, translate into practice, and with what consequences. In turn, the routine problems of Residency life shaped Residents’ ideas about how influence could, or should, be enacted going forwards. Only by reducing the scale of analysis can we tease out the relationship between ideas and practices and grasp how imperial influence operated on the ground.

Equally, narrowing the chronological scope enables this book to address a range of critical themes within the history of the Residencies, encompassing the broad spectrum of activities undertaken by the Resident at court. Histories of letter-writing, gift-giving, and flogging may not adhere to the same timeline, nor do they necessarily suggest a clear narrative arc; still, all are pertinent to how Residents understood and tried to express influence at court. Breaking with a traditional narrative structure permits us to bring topics that are conventionally treated separately within the same analytical frame.

Finally, by focusing on a small group of a dozen men, this book is better able to come to terms with the human dimension of the Company’s history, counteracting a widespread tendency to treat the colonial administration as an ‘agentless abstraction’ to quote Frederick Cooper.Footnote 62 Such an approach, Cooper argues, obscures the ways in which people confronted the possibilities and constraints of particular colonial situations, and acted accordingly. This book is premised on the idea that imperial policies were mediated through human beings with complicated relationships both to the institutions they represented and to the societies in which they tried, to varying degrees, to immerse themselves. This is not a work of prosopography; the focus remains on ideas and practices rather than on individual biographies. Still, by incorporating examples of individual dilemmas, we are reminded that imperial influence was a fabric stitched together out of a series of interactions and can identify some of the factors that might have shaped how this process played out.

In so doing, I have tried to create space for acknowledging how feelings of loss, loneliness, jealousy, or contempt informed how Residents perceived India as well as how they behaved there. In this, I have been compelled by Ann Stoler’s invitation to attend to ‘how power shaped the production of sentiments and vice versa’, to ‘dwell in the disquiets, in the antipathies, estrangements, yearnings, and resentments that constrained colonial policies and people’s actions’.Footnote 63 While in this instance Stoler was particularly concerned with the constitution and consolidation of racial boundaries through the regulation of interracial sex and procreation, her proposition seems equally relevant to the study of imperial governance more generally. Reading personal letters and journals alongside official reports restores some of the ambivalence and uncertainty that is elided in public records, exposing the fissures that emerged within the Company’s administration. In the process, it also becomes possible to challenge certain assumptions about the Residents themselves.

I.3 Demystifying the White Mughals

Though the Residents of the early nineteenth century rarely figure prominently in the historiography on indirect rule, they have had a disproportionate impact on debates about cultural syncretism. As intermediaries living at the interstices of British and Indian societies, the Residents are alluring figures for historians interested in connectedness and cosmopolitanism. Indian royal courts, and their attendant Residencies, are classic ‘contact zones’ where cultures mingled and overlapped.Footnote 64 A study of the Residencies intersects with wider interest in the ‘middle ground’, spaces where empires met, and lines of authority were blurred.Footnote 65 The Residents themselves, meanwhile, fit the rubric of cultural broker or go-between, agents who straddled cultural boundaries and made cross-cultural communication possible.Footnote 66 These were learned men, familiar with Indian languages, who immersed themselves to varying degrees in the swirling currents of courtly life. They partook of the symbolic exchanges that formed an essential part of Mughal ritual, chewed paan (a stimulating preparation of betel leaf and areca nut) and were christened with attar of roses. They smoked hookah and attended nautch dances; some took Indian wives. On the surface, at least, the Residencies seem like oases which, for a time, anyway, escaped what historian Sudipta Sen, among others, has characterized as the growing social and political distance separating Britons from Indians during this period.Footnote 67

Unsurprisingly, some of the most well-known scholarship on the Residencies tends to romanticize them as sites of cultural fusion, as hybrid spaces on the margins of British India. In White Mughals, William Dalrymple depicts these courts as ‘the borderlands of colonial India’, as ‘spaces where categories of identity, ideas of national loyalty and relations of power were often flexible, and where the possibilities for self-transformation were, at least potentially, limitless’.Footnote 68 This language is echoed in Maya Jasanoff’s study of imperial collectors, where Lucknow is portrayed as a city that furnished its inhabitants with ‘genuinely multicultural possibilities’, offering ‘the promise of reinvention in its cosmopolitan embrace’. According to Jasanoff, ‘who you were, with whom you associated, and how you wanted to live were not either-or choices. You could bridge the boundaries’.Footnote 69 This strain of historiography resonates with a ‘postmodern’ intellectual tradition that uses the concept of border in a metaphorical sense to highlight the juxtaposition of cultures in particular places, tending to represent such spaces as ‘zone[s] of cultural play and experimentation’.Footnote 70 Dalrymple and Jasanoff’s findings have served to reinforce the historical commonplace that eighteenth-century understandings of human difference were more fluid and contextual than nineteenth- and twentieth-century conceptions of race.Footnote 71 The Residents, in this account, are used as evidence to suggest that Britons in India during this period acculturated and integrated into their new surroundings.

This emphasis on exchange and acculturation underplays the Residents’ primary function as political agents. To be sure, Residencies were certainly seen to provide opportunities for staging cross-cultural encounters. Visitors to the subcontinent commonly toured Lucknow and Pune; both courts feature prominently in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century travelogues.Footnote 72 Here, European guests were treated to breakfast parties, hunting expeditions, elephant rides, and firework displays. Still, this veneer of polite sociability did not obscure the unequal dynamics at work in these places. For contemporaries, these were also sites of coercion and control, arenas wherein the Company asserted its right to dictate to its neighbours. Former Resident Richard Jenkins proclaimed to the 1831 parliamentary select committee that the subsidiary alliance system was ‘the main source of our ascendancy, both military and political; it has grown with our growth; and strengthened with our strength. It is interwoven with our very existence’.Footnote 73 This statement might have been intended to burnish Jenkins’s own reputation as a former Resident, but it was not an exaggeration. The objective of this book is thus to strip away some of the allure of the Residencies, to penetrate past the lavish exteriors of their palatial courts and the decorous, ceremonial forms and practices that Residents adopted to get at the heart of their work. This work involved espionage, patronage, war, and coercion as much as it did spectacle; the Residencies were as much spaces of empire as the courthouse or the counting room.

Incorporating the Residencies into this picture of the Company changes our views of British imperialism in India at the turn of the nineteenth century, an era that has been identified as particularly significant to its history. In Imperial Meridian: The British Empire and the World 1780–1830 (1989), C. A. Bayly influentially depicted 1780 to 1830 as a vital phase of British imperial history characterized by territorial expansion, increased state intervention, and the development of new techniques of governance.Footnote 74 Building on this foundational history, the period figures prominently in recent studies dedicated to charting the hardening of racial boundaries and the emergence of modern governmentality in India, tracing how locally specific practices were reconfigured or displaced by abstract principles of rule in the realm of political ideology, land legislation, legal reform, and record-keeping and documentation.Footnote 75 The Residencies, however, do not neatly fit these overarching patterns. Here, Residents had no choice but to work within frameworks not of their choosing and were required to interact with Indians of various backgrounds whether they liked it or not.

How do we reconcile these two pictures of the Company’s empire? Though Imperial Meridian is usually cited with reference to the centralizing, authoritarian impulses that it identified, the book also highlighted the patronage of indigenous landed elites as an important feature of the British empire during this period.Footnote 76 In so doing, Bayly had in mind not so much the merchants, bankers, and brokers who have long been recognized as indispensable to the Company, but rather the aristocracy of South Asia. In part, what the Residencies demonstrate are the points of commonality between British and Indian political elites that made empire possible. Although there were important differences between British and Indian political culture in the early nineteenth century (which this book will elucidate), there were also aspects of Indian courtly etiquette, patronage and service relationships, and gender and the family that aligned with British habits and assumptions. Contemporaries remarked more on contrasts and compromises than congruences, seemingly because many of the things that elite Britons and Indians had in common were also things that were taken for granted or assumed to be natural on both sides; yet these commonalities provided a foundation upon which understandings could be reached. Residents sometimes drew stark oppositions between British and Indian society, but their assertions should be read critically. In so doing, these men were engaging in what legal historian Anthony Anghie has termed the ‘dynamic of difference’, the ‘process of creating a gap between two cultures, demarcating one as universal and civilized, and the other as particular and uncivilized.’Footnote 77 Rather than taking the Resident at their word, we should make our own comparisons to better contextualize this dynamic process of interaction and exchange. The period was undoubtedly one of chauvinistic nationalism, but the example of the Residencies reminds us of the ongoing importance of strategies of negotiation and appeal, suggesting that patronage, gifts, and favours were as much instruments of imperial power as tax collection or the law. After all, it was by incorporating themselves into Mughal frameworks of submission and service that the Company had acquired its political and commercial foothold in India in the first place.Footnote 78 This book demonstrates the continuing importance of political interaction and exchange into the nineteenth century, even if the dynamics had shifted.

Though the Residents moderate our views on Britain’s imperial meridian, it is also a case of the exception proving the rule; through the Residents, we see how determinedly the Company’s executive tried to mould the Residencies to fit a bureaucratic pattern of their choosing, even in the face of determined resistance from Residents themselves. The Residencies were thus points of friction where some of the most intractable problems of empire played out. The Residents’ close working relationships with Indian elites, for one, means that Residencies provide a useful site for thinking about the tension between domination and exchange upon which the Company’s operations relied. The Residents were charged with conciliating Indian rulers and accommodating themselves to Indian political culture, all while maintaining the image of difference on which the imperial project in India was ideologically predicated. While Residents and their superiors believed, to varying degrees, that it was important to express political power in ways that were intelligible to the surrounding population and that resonated with local conceptions of political legitimacy, they were also wary of undermining the reputation for British moral probity and rule of law that they desired to cultivate. The Residents were thus put in a double bind. To establish themselves at Indian courts they had to engage, to some extent, with Indian political culture; in so doing, however, they threatened to subvert the carefully constructed differences, between ‘civilized’ Britons and ‘barbarous’ Indians, upon which the legitimacy of the Company’s administration was believed to rest. Because of this paradox, Residents were in regular disagreement with their superiors about issues ranging from the purchase of gifts to corporal punishment.

As this suggests, the Residencies are also sites where the divisions within the Company most clearly come into view. Historians of the Company have long recognized the existence of an ‘agency problem’, whereby authorities in London struggled to control the activities of employees overseas.Footnote 79 Given their geographical distance from the Company’s political centres, the Residents exemplify in perhaps its most acute form the distrust that distance could generate. As Duncan Bell has observed, from the perspective of nineteenth-century thinkers the problem of distance inhered, not simply in the practical, administrative difficulties posed by travel and communication, but also the attenuation of crucial bonds of loyalty and citizenship.Footnote 80 Suspicions about the corruptibility of the Residents’ character were intensified by their relative isolation. The Residents, for their part, were liable to regard the Company’s executive as a distant entity from which they could expect little support or recognition. As the man on the spot, Residents exercised significant discretionary power, but were easily scapegoated if problems emerged at court. Although the Residents and the governor general were in near constant correspondence, their relationship was fragile. Some Residents earned the governor generals’ respect, even their deference, but good relations depended on the Resident’s ability to anticipate and implement the will of government, a will that was not always clear or well informed where Indian allies were concerned.

Contrary to existing depictions of an ‘agency problem’, then, the reasons for the rampant distrust within the Company were more complex than the geographical distance separating Residents from London and Calcutta. Ideological divisions within the Company were compounded by wider transformations in British conceptualizations of public life and the duties of office. In Britain, the administration of William Pitt the Younger (1783–1801) took tentative steps towards abolishing sinecures, regulating the profits of office, and introducing salaries in place of fees.Footnote 81 These reforms reflected a greater demand for transparency and accountability, as official activity was increasingly dissociated from private life, and public assets were being more sharply distinguished from private wealth.Footnote 82 Similar attitudes operated within the Company; historians have described at length the anxieties about corruption within the Company in the eighteenth century, and subsequent attempts to reform it.Footnote 83 Efforts to refashion the Company’s employees persisted into the nineteenth century, as evidenced, for example, by the foundation of the Company’s college at Haileybury.Footnote 84 At the Residencies, the tensions generated by changing ideas of public office, and the shifting domains of private and public life, were at their most intense; by focusing on the Residents, it is possible to witness first-hand the divisiveness of an ‘age of reform’.Footnote 85 For reasons that will become apparent in the course of this book, this emergent professional ethic proved particularly troublesome to inculcate or impose within the Residency system, long after the golden age of the nabob was supposedly over. In opposition to the wave of reformist enthusiasm coursing through the nineteenth-century Company, Residents like Mountstuart Elphinstone and Charles Metcalfe have been identified as ‘Romantics’, ‘the true conservative element’, who opposed ‘the tendency that would transform British rule from a personal, paternal government, to an impersonal, mechanical administration’, to quote Eric Stokes.Footnote 86 By situating these ideas within the courtly environments in which they took shape, this book exposes important practical and ideological divisions within the Company’s operations.

Finally, as intermediaries working within and between British and Indian regimes, Residents were also well placed to reflect on issues of continuity and change. One of the driving questions of the historiography on ‘British’ India is the extent to which the Company’s administration differed from existing Indian polities, and how far its expanding presence fundamentally transformed Indian politics and society.Footnote 87 Recent studies in the realm of tax collection, administration of justice, record-keeping, and the military have demonstrated how the Company drew on existing social and political structures and, in the process, reconfigured them in profound and sometimes unexpected ways.Footnote 88 At Indian royal courts, the question of whether to adapt to existing political culture, or to remodel it according to British mores, had added stakes given the dangers of either undermining the existing regime, or inciting it to resist. Residents wanted to maintain the structural integrity of Indian administrations, while at the same time channelling their resources into the Company’s coffers. Experiences at Indian courts forced Residents to reckon with the fact that their mere presence could provoke unexpected effects that worked against this political agenda, sending courtly politics spiralling in unanticipated directions. Some Residents even came to recognize the relative impossibility of maintaining the status quo given the intrinsically exploitative character of the Company’s relationship with its supposed allies. The Residents therefore provide an ideal lens for examining contemporary perceptions of the nature and impact of imperial intervention during a period that C. A. Bayly identified as ‘the first age of global imperialism’.Footnote 89

I.4 Approach

Rather than constructing a broad chronological narrative, this book focuses on a brief, coherent, and historically significant unit of time when some of the most important subsidiary alliances were concluded. In 1798, the subsidiary alliance system was still in its infancy; its underlying principles and mode of operation were still in being worked out, and certain key Indian powers, notably the Marathas, remained outside its remit. By 1818, the subsidiary alliance system had brought most of central India under the Company’s influence, but only after many years of debate within the Company, and resistance on the part of Indians of various backgrounds. It is this contested process, and the generation of Residents responsible for it, that lie at the heart of this book.

As a complement to existing works of regional expertise, the emphasis of this book is on detecting patterns across courts. This is not to suggest that the histories of these courts are interchangeable; to the contrary, their trajectories differed in important ways. Most obviously, they had different relations with the Company, resulting in varying levels of intervention by the Resident. At one extreme, the Resident at Delhi effectively ruled in the Mughal emperor’s stead following the Company’s occupation of the city in 1803, and was accordingly charged with a range of responsibilities over neighbouring districts that other Residents did not have.Footnote 90 At the other end of the spectrum, the Residents attached to Shinde and the raja of Berar were essentially ambassadors with little influence over state administration, since neither Shinde nor the raja were then bound to the Company through subsidiary alliances. While these courts were all considered sufficiently significant for their Residents to fall under the direct purview of the governor general, they were important to the Company for different reasons. Nagpur’s location at the centre of the subcontinent made it a coveted military and communications hub, while Travancore was considered as a likely staging post for a French invasion at the turn of the century as well as a valued source of timber and pepper. Awadh furnished money and military labour and occupied a strategic location as gateway to the North Indian plain.Footnote 91 Meanwhile, Company control over Delhi and Pune was seen to have symbolic significance because of their status as political capitals. Throughout the book, I have tried to bring some of these distinctions to the fore, indicating, as much as possible, where paths diverged as well as where they intersected.

Though the courts were unique in many respects, it is nevertheless worth considering them together because both British and Indian contemporaries explicitly made these connections and comparisons at the time, as Chapter 2 in particular will illustrate. The Indian political elite were attuned to developments at different political centres through the exchange of letters, ambassadors, and spies; this awareness informed their strategizing. The Company, for its part, was conscious of the scrutiny they were under and the ripple effect that could ensue because of shifts in practice or policy at a single court. The Company’s aim during this period was precisely to divide political centres that had previously been in regular contact. By the same token, part of the strength of the Residency system was its networked character; Residents passed on information and experiences and learned from the examples set at other courts. The individual Residencies made up a system, a ‘political line’ (as contemporaries called it) characterized by the exchange of people and ideas; examining the Residents in isolation would obscure how this system operated. To demonstrate this point, throughout the book I have highlighted the ways in which exchanges between courts, and between their respective Residencies, shaped the development of ideas and practices of imperial influence.

If the courts examined in this study differed significantly one from the other, so, too, did many of the Residents. Some fit the ‘White Mughal’ mould, either because they cohabited with Indian women, dressed in Indian garb, or delighted in Indian literature and history. Some, for example, were adepts in Indian languages; Thomas Sydenham was described in his obituary as ‘master of the Arabic and Persian languages’, and by a colleague in the political line as ‘a most eminent Hindostannee in language & manners’.Footnote 92 Other Residents couldn’t be bothered; as a young man, Charles Theophilus Metcalfe determined not to waste his time with Oriental scholarship, convinced ‘that the Nations of Europe have so far surpassed any thing ever known in Asia that the world would not gain one atom of real information, from the disclosure of all, that is contained in Eastern languages.’Footnote 93 Some Residents were seemingly happy to remain in India forever, while others viewed their time in India as a liminal period to be endured before their real life could resume; in letters to friends, Mountstuart Elphinstone described his Company service as his ‘period of transportation’ (comparing himself to a convict) and despaired about the ‘waste of years’ separating him from his return to Britain.Footnote 94 Politically a few favoured conciliation, but growing numbers believed in the necessity of coercion, for reasons that will be explored in Chapter 3. Rather than trying to construct an ideal type or identify a paradigmatic example of how a Resident thought and behaved, then, this book instead recaptures the experimental nature of early attempts to consolidate the Company’s political predominance. The Residents differed in their interpretations of what their influence should look like, and how it should be exercised. In drawing attention to this variety, the book illustrates the spectrum of possibilities available at this protean moment in the history of the Company’s diplomatic line.

The examination of the routine practices of this small coterie of imperial officials might seem like a return to the study of ‘great men’, replicating the triumphal imperial accounts of the nineteenth century. To some extent, this focus on the Company’s representatives runs counter to prevailing trends within global history, where there is a laudable preference for recovering the experiences of previously marginalized individuals at the expense of the subjects of nineteenth-century hagiography. In contrast to the convicts, captives, sailors, slaves, and indentured labourers studied by historians like Clare Anderson, Residents like Mountstuart Elphinstone and Charles Metcalfe were recognized as leading figures in their own lifetimes.Footnote 95 They are, even now, sometimes described in terms bordering on veneration, as an ‘extraordinary galaxy of distinctive stars in the political firmament’.Footnote 96 Of the four ‘great men’ of the ‘golden age’ identified by Philip Mason in his celebratory The Men Who Ruled India (1985), two were Residents; Metcalfe was described as ‘the last and probably the greatest of the quartet’.Footnote 97 This lingering aura of adulation makes it even more important that we examine how these individuals self-consciously constructed themselves to appear powerful and authoritative, usually at the expense of Indian elites who they worked systematically to disempower and discredit. In examining their professional trajectories, we see how their actions were shaped by the activities of Indians of various backgrounds, whether messengers, accountants, translators, or concubines. In their day-to-day work, the Residents were forced to respond to circumstances not of their making; they adapted in response to Indian resistance and relied on Indian aid. Throughout the book, but especially in Chapters 5 and 6, we see the significance of Indian actors to this history.

Although this book is concerned to bring the impact of Indian actors to the fore, it is in essence a history of British imperial ideas and practices. As such, it relies on Company records and the Residents’ personal papers. These sources, though voluminous and often rich in detail, are inherently problematic. To be sure, every archive is by its nature partial and incomplete; record-keeping is a selective process, and the decisions made about what to keep and what to destroy are both reflective and constitutive of an unequal world wherein some voices are amplified at the expense of others.Footnote 98 The importance of record-keeping to state-formation means that archives should be understood not as neutral repositories of information but as instruments whereby political power is exercised.Footnote 99 These traits are evident in imperial archives, too; nevertheless, imperial archives possess unique features that make them particularly suspect as windows onto the past. For the most part, imperial records represent an outsiders’ point of view, with the testimony of indigenous populations filtered through the prism of a colonial official’s interpretation and recorded and preserved according to his priorities. The contents of imperial archives also served distinctive ideological purposes. These records were used to construct and justify inequality along racial lines as well as to give substance to the fantasy of an all-knowing colonial administration which, historians argue, dramatically misrepresents officials’ real grasp of realities on the ground.Footnote 100 The Residency records are a product of their imperial environment; their role was not simply to describe, but to reinforce political asymmetries. They must be read in terms of the functions they were intended to serve, as well as the colonial common sense that shaped them and was in turn shaped by them.

The Residents’ personal papers can offer a valuable counterpoint to official records; they contain evidence of uncertainty and dissent that rarely features in letters destined for the eyes of their superiors. Yet, letters are not a transparent reflection of a person’s inner life, either. Letters, like records, are prone to damage, destruction, and redaction. Recent scholarship on epistolarity emphasizes the extent to which letter-writing was a performance, ‘an “act” in the theatrical sense as well as a “speech-act” in the linguistic.’Footnote 101 Letters were written with an audience in mind; their language and contents were tailored for a purpose. An important consideration for letter writers was the probability that their letter would become public, given that it was common practice to forward letters of interest to friends, kin, and colleagues, or to read them aloud in company. Even when writing to family in Britain, then, Company men engaged in understatement, misrepresentation, or embellishment; Sarah Pearsall, describing the correspondence of trans-Atlantic families in the late eighteenth century, argues that many letter-writers used emotive and sentimental language as a means of manufacturing intimacy with geographically distant friends and family, as well as out of a desire to conform to literary and epistolary conventions that emphasized spontaneity and sensibility.Footnote 102 Letters were therefore instruments through which Residents endeavoured to represent and thus in a sense produce identities and relationships. The Residents’ letters should be treated as part of the repertoire of strategies that were used to cement their position at court.

Whereas Residents’ ties to friends and family can be gleaned from the many rambling letters that have survived, the interactions between Company Residents and courtly elites are some of the most compelling, yet often frustratingly opaque, aspects of the Residents’ work. To understand these relationships, this book relies on the reams of letters and petitions authored by Indians of different backgrounds that fill the Residency records. These sources are crucial to our understanding of the Residents’ place at court and his interactions with employees and royal family members, but they also raise problems of their own. Petitions are often highly formulaic, written in deferential language, with the aim of convincing. Though their language and format might vary, most letters submitted to the Resident were also written with some specific purpose in mind, and in accordance with epistolary conventions. These texts were instruments for making claims and cannot be read as objective representations of Anglo-Indian relationships. Still, they can be revealing. By identifying the demands that Indians made upon the Company, and the ways in which these demands were explained or justified, we can acquire some insight into how Indians at court viewed the Company, and what they hoped to gain from it.Footnote 103 As a result, we can reconstruct some of the transactions that prompted and sustained these cross-cultural relationships, making the Company’s growing political influence at Indian royal courts possible.

I.5 Chapter Outline

Chapter 1 sets the stage by demonstrating the significance of the years 1798–1818, on which most of the analysis is centred. Specifically, it shows that while the developments of 1798–1818 can be situated within a longer history of political experimentation, this period nevertheless witnessed a crucial shift, in which a concept of British paramountcy was born out of a set of ideas and practices to be explored in the succeeding chapters. By comparing this period with the history that preceded it, and then briefly tracing its legacy over the following decades, Chapter 1 establishes this moment as one worthy of in-depth analysis.

The following three thematic chapters delineate the key strategies that Residents employed to establish positions of influence at court, and the obstacles that they confronted in so doing. At the heart of Chapter 2 are the tactics that the Residents developed for collecting and mobilizing political intelligence. Knowledge and knowledge-making occupy a central place in the historiography of colonial South Asia, but the Residents’ crucial role in this process, as informants stationed at the courts of rival Indian powers, remains understudied. This chapter highlights the difficulties that the Residents encountered in trying to sew written, oral, personal, and institutional channels of information into a seamless whole. Chapter 3 considers the disputed role of violence as both an ideological justification for Company intervention and as a mode of imperial authority, contributing significantly to our understanding of eighteenth-century views on the use of force in imperial settings. Chapter 4 analyses the financial disputes that proliferated within the Residency system, highlighting the political and ideological dimensions of seemingly petty squabbles surrounding money spent on gift-giving and display. Together, these three chapters show how changing views of the Company’s place in the subcontinent manifested themselves in the routine business of empire, exacerbating latent divisions within the Company created by distance, distrust, and conflicting interests.

The next two chapters focus in greater depth on the Resident’s interactions with Indians at court, and the importance of these transactions to the evolution of the subsidiary alliance system. Chapter 5 examines the close yet controversial relationships that developed between Residents and their Indian secretaries, known as munshis. Although historians have long recognized the important roles that Indian experts played in the Company’s operations, the focus has usually been on the mechanics of direct rule in ‘British’ India. Yet, the expertise of Indian cultural intermediaries was arguably even more important, as well as more contested, in the context of the Company’s growing political influence over nominally independent Indian kingdoms. This chapter considers how relationships with Residency munshis were conceptualized and debated by British officials and reflects on the practical consequences of these relationships for the Residents and munshis involved. Chapter 6 emphasizes the importance of royal family members in shaping and resisting the Company’s presence at court. Dynastic intrigue and revolt greatly complicated Residents’ attempts to consolidate influence at Indian royal courts. This chapter shows not only how Residents sought to manage royal family members for their own purposes, but also how royal family members, particularly royal women, were themselves able to lay a claim on the Resident’s services. Together, these two chapters bring to light the quotidian substance of the confrontation between British Residents and the Indian elite, showing how Indians of different backgrounds enabled, resisted, and profited from the Resident’s presence at court. By its very nature, the subsidiary alliance system implied working with and through Indian elites, but, as these chapters show, this was far from simple or straightforward for colonial officials to do.

Taken together, these chapters illustrate the multifaceted nature of the Resident’s work and the different, mutually reinforcing foundations of his influence at court. Yet, they also show that on all fronts the Resident’s activities were questioned or undermined by colleagues within the Company as well as by Indians at court. Within the Company, contemporaries debated different styles of rule, and these practical and ideological divisions were exacerbated by mutual suspicions resulting from geographical distance and the blurring of personal and public interests in the diplomatic line. This process was further complicated by the need to work through Indian elites and administrators with interests of their own. Theoretically, the system of alliances was supposed to make things easier for the Company, allowing them to exercise political control over the subcontinent without shouldering the burden of internal administration. Practically, this influence proved difficult to enforce. Contrary to British hopes and expectations, Indian rulers often did not make for willing or accommodating instruments for achieving Company interests. This period would be remembered in nineteenth-century hagiography as one wherein the Company’s supreme authority was established through the energetic activities of political and military masterminds, but the view from the ground, as we shall see, was far less triumphal.