Introduction

Every January, Hong Kong celebrates the ceremonial opening of the legal year. The chief justice gives a speech in English celebrating the rule of law and the judiciary's guardianship of it.Footnote 1 The “overseas” judges on Hong Kong's highest court, the Court of Final Appeal (CFA),Footnote 2 rarely attend. This year, Chief Justice Andrew Cheung probably meant to reassure his audience when he confirmed that overseas judges could sit in “national security” cases, applying a draconian 2020 law that could punish speech at home and abroad.Footnote 3 But that promise instead strengthened calls for the overseas judges on the CFA to resign.Footnote 4 In March 2022, two more overseas judges—the current president and deputy president of the UK Supreme Court—resigned, breaking the long-standing tradition of having two members of that court on the CFA.Footnote 5 Several remaining judges published statements explaining their commitment to Hong Kong's rule of law.Footnote 6

“Traveling judges” are those who—like Hong Kong's overseas judges—travel from their home jurisdictions to serve on another jurisdiction's court. We refer to “traveling”Footnote 7 rather than “foreign” judges for three reasons. First, it avoids complicated citizenship questions. Second, it focuses on trans-jurisdictional (rather than only transnational) travel.Footnote 8 To differentiate Delaware judges and courts from Nebraska ones,Footnote 9 for example, we identify judges by their “home jurisdiction,” the place of their primary legal career.Footnote 10 Third, traveling judges often offer potential litigants not foreign-ness but familiarity—London-based counsel can appear before a London-based judge in Dubai, Kazakhstan, or the Cayman Islands.

A growing body of scholarship examines the emergence of courts or divisions focused on international commercial disputes.Footnote 11 Several of these courts have followed Hong Kong's lead and hired traveling judges. Studies of foreign judges, however, tend to focus on constitutional law and ignore most of these courts.Footnote 12 Scholarship on the rise of international commercial courts,Footnote 13 meanwhile, has not yet focused rigorously on the decision makers,Footnote 14 often assuming they resemble arbitrators.Footnote 15

This Article begins the study of traveling judges on commercially focused courts by identifying who they are, where they serve, and what roles they play. In some ways, they repeat old patterns. Traveling judges are overwhelmingly from the UK and former dominion colonies. They are less diverse than international arbitrators and far more likely to have judicial experience. A look at their backgrounds suggests that traveling judges might be a phenomenon limited to common law countries, but only half of hiring jurisdictions are in such states. Almost all, however, are small jurisdictions that are or aspire to be market-dominant.Footnote 16 Traveling judges offer hiring jurisdictions a method of transplanting well-respected courts, like London's commercial court, on their shores. They recreate these courts, however, in new political environments under the supervision of different states. They may therefore face different constraints, destined to change over time, which will affect both hiring jurisdictions’ ability to achieve their goals and traveling judges’ ability to judge in the way they are accustomed.

The stakes are high. As these courts proliferate, they are poised to exert increasing influence over dispute resolution, law development, and global judicial governance.Footnote 17 Traveling judges may improve international commercial dispute resolution around the world, promote rule of law values, and contribute to convergence in commercial law or even civil justice. But they could also promote a neocolonial world order that harnesses certain jurisdictions’ sovereignty to sustain a commercial law that benefits some multinationals at the expense of the global community more broadly defined.Footnote 18

A better understanding of traveling judges will contribute to studies of judges, judicial identity, and judicial legitimacy, among other areas. Private international law and international economic law scholars may study these courts and their judges’ role in promoting foreign investment, the market for law and dispute resolution, and the harmonization and convergence of international commercial law. Historians may appreciate traveling judges’ implications for the legacy of colonialism and the legal origins debate. Political scientists may view traveling judges as a window into debates about democratic accountability, institution building, and legal transplantation. And legal scholars more generally may be interested in what this phenomenon reveals about the development of public and private law, the boundaries between them, and the relationship between international dispute resolution and national sovereignty.

This study focuses on traveling judges on courts that handle international commercial disputes, in particular members of the Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts (SIFOCC).Footnote 19 We determined which SIFOCC member courts hire traveling judges,Footnote 20 collected extensive information about the courts and the judges,Footnote 21 and interviewed over twenty-five judges and court personnel. This study uses grounded theoryFootnote 22 to contribute to the growing methodological fields of empirical and social science approaches to comparative lawFootnote 23 and international law.Footnote 24 It also incorporates legal history to develop explanations for why these jurisdictions hire these traveling judges.

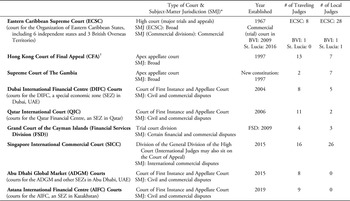

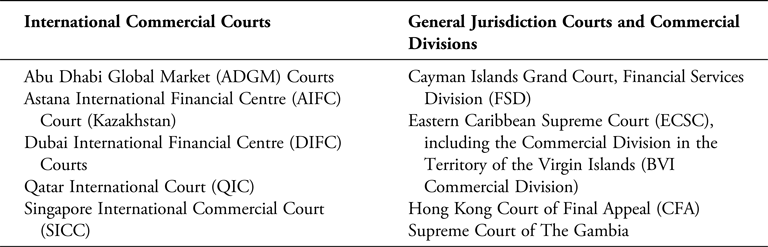

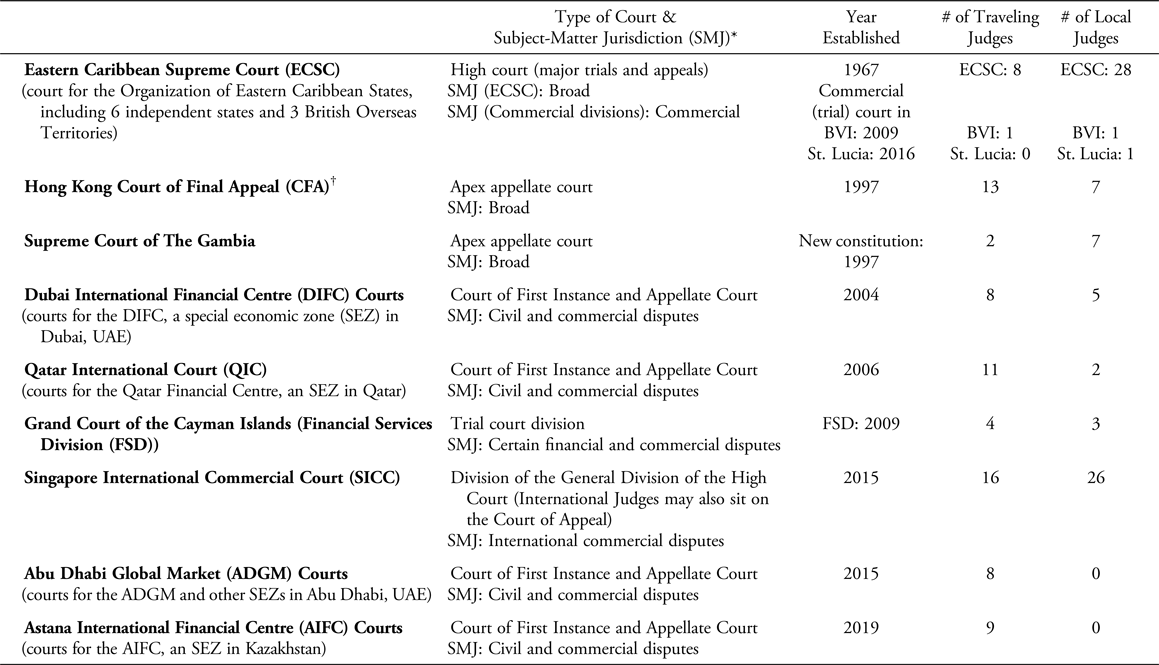

Out of forty-four SIFOCC members, nine employed traveling judges as of June 1, 2021.Footnote 25 In addition to the Hong Kong SAR judiciary, this group includes the Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC), a division of the high court of Singapore with jurisdiction restricted to international commercial disputes; four court systems for new special economic zones (SEZs) in oil-exporting states—the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC), the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM), the Qatar Financial Centre (QFC), and the Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) in Kazakhstan—all of which limit jurisdiction to civil or commercial disputes; two commercial courts in the Caribbean—the Cayman Islands Financial Services Division (a division of the Cayman Islands Grand Court) and the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court (for which we focus on the British Virgin Islands (BVI) Commercial Division); and the Supreme Court of The Gambia.Footnote 26

To make sense of this list, this Article identifies the common features of these jurisdictions and their courts, while acknowledging their many differences. Half are located in common law countries. All but one are in former British colonies or protectorates.Footnote 27 The jurisdictions in this study—including the SEZs in the oil states—all follow the common law tradition. Either by way of colonial legacy or by recent legislation, these jurisdictions have adopted substantive law and procedures that mirror those in London to varying degrees. The most commercially oriented courts are in small jurisdictions that are or aspire to be “market-dominant” with an outsized influence in global finance.Footnote 28 Political and judicial leaders in these jurisdictions have designed these courts for cross-border disputes, anticipating transnational parties.

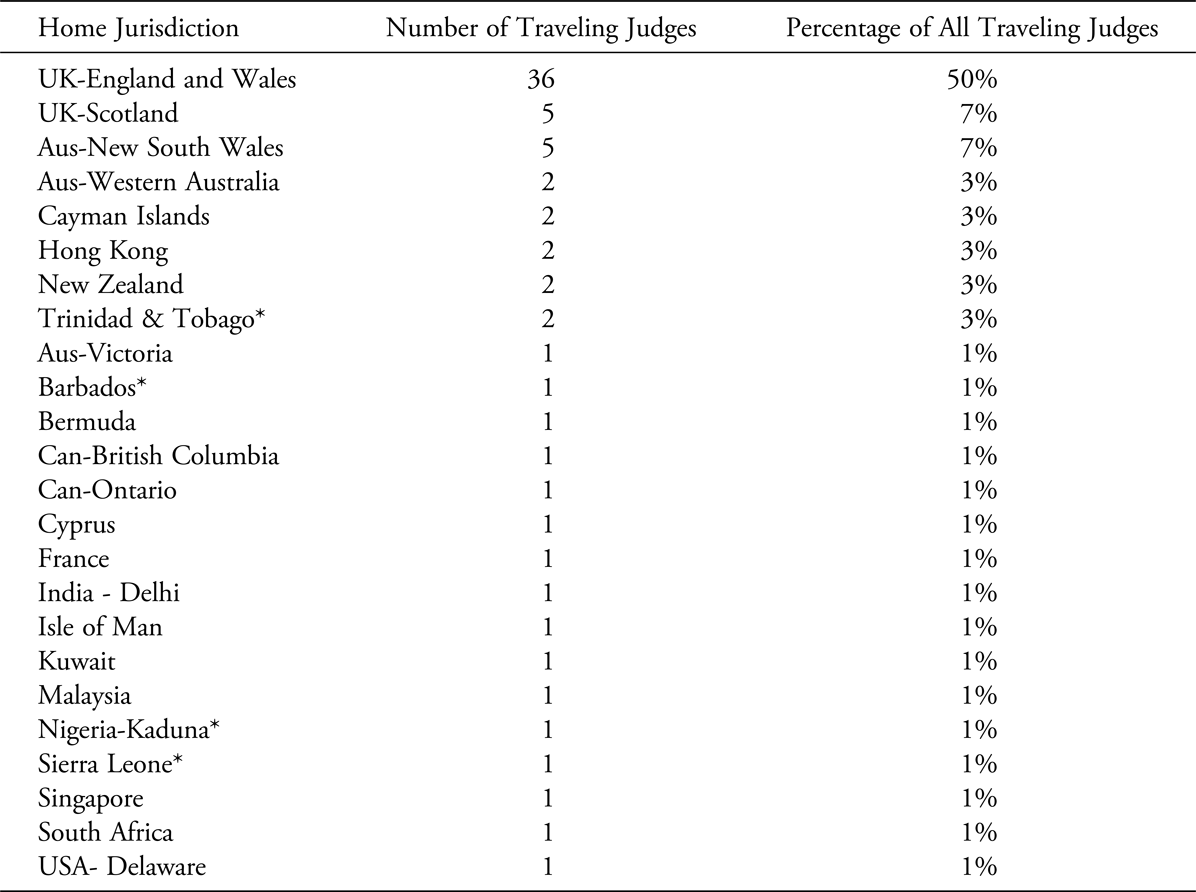

Some courts have only a few traveling judges on a mostly local bench. Two courts employ 100 percent traveling judges.Footnote 29 As of June 1, 2021, we identified seventy-two sitting traveling judges on all courts included in our study. Several judges sat on two or more courts.Footnote 30 They were overwhelmingly white, male, retired judges.Footnote 31 Nearly seventy percent also acted as arbitrators, often spending more time as arbitrators than as traveling judges.

Considered as a group, the traveling judges reveal a stark British influence. Most have some UK-based legal education. About half are from England and Wales. The remainder come from other common law or hybrid jurisdictions, with no single other jurisdiction providing more than five traveling judges, and most providing only one or two. Despite the prominence of New York and Delaware commercial law, we found only one U.S. traveling judge.Footnote 32

The demographics of traveling judges reflect the way hiring governments seek to appeal to foreign investors, which in turn reflects not only colonial history but also the rise of international commercial arbitration and perceptions about what legal environments are most business-friendly. Judge demographics also reflect constraints on sought-after individuals’ willingness and desire to serve as traveling judges, which may be informed by their home jurisdictions’ judicial retirement age and by judges’ post-retirement career options.

In addition to these empirical and analytical contributions, this Article examines some implications of our study, all of which reveal a reassertion of state power in international commercial dispute resolution. First, traveling judges’ demographics reflect the hiring jurisdictions’ use of the English common law tradition—and its judges—to further their foreign investment goals. Our results undermine arguments that transjudicial global networks are becoming less dominated by earlier hegemonic powersFootnote 33 and support studies of the domination of English common law in the coding of global capital, linking today's legal arrangements to colonial history. Second, although traveling commercial judges resemble international arbitrators, comparing those groups suggests that hiring jurisdictions prioritize certain elements—including judicial experience and nationality—differently than parties do when appointing arbitrators. Third, different host governments and local circumstances may create obstacles to the courts’ ability to achieve their various goals and to traveling judges’ ability to judge in the ways they may be accustomed to judging in their home jurisdictions.

The Article proceeds as follows. Part I provides historical background and reviews the literatures on foreign judges and international commercial dispute resolution. Part II describes our methodology. Part III reports our findings on who traveling judges are, how they are hired and paid, how they may be removed from office, and what they do while in office and on the side (as most traveling judge positions are part-time). Part IV analyzes which courts hire traveling judges, why they do so, why the judges are available, and why they choose to accept the invitation. Part V discusses implications relating to English legal dominance, judicial identity, and the rule of law.

Glossary of Court Names

I. Traveling Judges and Commercial Courts

The courts in this study are in places with three kinds of histories—former British colonies that had colonial courts (the Caribbean, Hong Kong, The Gambia, and Singapore), former British protectorates that had consular courts (the UAE and Qatar), and one that was neither (Kazakhstan). The courts that hire traveling judges are all less than thirty years old; many are less than ten.Footnote 34

This Part first explores the history of traveling judges in these jurisdictions. It then discusses the literature on foreign judges and global judicial dialogue to identify how traveling judges in the commercial context resemble and differ from foreign judges in other contexts. Finally, this Part discusses the latest developments in international commercial dispute resolution—in courts and arbitration—to better understand the role of traveling judges in this emerging landscape.

A. The History of Traveling Judges

Internationalized courts run partially by foreigners and that adjudicate disputes involving foreign parties have a long history, dating back to the Roman Empire and involving both common law and civil law traditions.Footnote 35 Regions outside the British Empire also had tribunals run by and for foreigners, “mostly built upon a French legal foundation.”Footnote 36 This Section provides a short history of the influence of English law and judges in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Today, the array of common law judiciaries and the global legal profession—as well as modern traveling judges—reflect this history.Footnote 37 While often omitted from studies of international commercial courts,Footnote 38 this history helps to explain today's traveling judges.

The British Empire used colonial judges to create the foundation of a shared common law tradition based on English law and language.Footnote 39 The degree of imposition of English legal influence depended on a jurisdiction's status within the British Empire.Footnote 40 In colonies like Singapore and the Cayman Islands, the Empire imposed portions of its law and legal structures, including by establishing colonial courts—local common law courts intended to promote and protect commercial development.Footnote 41 In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, colonial court judges were primarily English, Scottish, and Irish barristers, but the dearth of desirable candidates eventually forced the Colonial Office to consider candidates from the dominions of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.Footnote 42 It was understood that candidates would be white.Footnote 43 Applicants included both individuals who had not made a sufficient living on the home islands and others who “came from families with a tradition of living in British territories abroad.”Footnote 44 Final appeal from colonial courts was to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC), a tribunal seated in London that originally included only UK judges, but came to reflect a more diverse bench of (male) judges from across the empire.Footnote 45

In protectorates, like the Trucial States (now the UAE) and Qatar, the British government lacked direct control and did not impose a common law legal system. These states were governed by tribal law, Shari'a, and customary law.Footnote 46 As the region developed in the 1940s and British interests shifted from military strategic to financial with the discovery of oil, the British government required ruling sheiks to cede jurisdiction over British subjects to Britain because they did not trust the local courts.Footnote 47 The resulting consular courtsFootnote 48 heard disputes involving British citizens, other foreigners, and their interests.Footnote 49 As with colonial courts, final appeal from consular courts was to the JCPC.Footnote 50 The local courts maintained jurisdiction over Muslim residents.

When some former colonies and protectorates established independence in the 1960s and 1970s, some continued to employ now-foreign judges on their courts.Footnote 51 The JCPC sometimes retained jurisdiction over final appeals. Other territories—including Hong Kong, the Cayman Islands, and the BVI—did not become fully independent.Footnote 52 Over time, they developed benches with a mix of local and traveling judges.Footnote 53 Appellate courts over these territories likewise had traveling judges, such as the Hong Kong CFA, which in 1997 replaced the JCPC as the court of final appeal for Hong Kong.Footnote 54 In the Caribbean, the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court (ECSC), established in 1967, combined first-instance and appellate jurisdiction over both newly independent countries like St. Lucia and some remaining British Overseas Territories like the BVI.Footnote 55 ECSC judges must have previously served as a judge or practitioner “in some part of the Commonwealth,” but not necessarily in an ECSC member states.Footnote 56 The JCPC—today made up of the justices of the UK Supreme Court—has continued as the final court of appeal for many jurisdictions,Footnote 57 including most ECSC jurisdictions, placing British judges with extraterritorial jurisdiction at the judicial apex of both British territories and several independent states.Footnote 58

In the Middle East, independence also brought legal reform. Advised by regional experts and borrowing heavily from European legal regimes,Footnote 59 the UAE established local courts that followed a mixture of Shari'a law and civil law traditions.Footnote 60 Qatar likewise maintained a dual legal system with Shari'a courts and the secular, civil law Adlia court, with jurisdiction over non-Muslims.Footnote 61

B. Foreign Judges and Judicial Globalization

The practice of foreign judges sitting on domestic courts is a “largely under-studied phenomenon,”Footnote 62 but the interaction of national and international judges has been studied extensively. In the mid-2000s, Anne-Marie Slaughter identified a “global community of courts” wherein judges traveled not to sit on other courts, but to meet to discuss common problems.Footnote 63 Slaughter suggested that unlike the colonial past, when national judiciaries received an empire's law, the “global community of courts” had transitioned to dialogue with other countries’ laws,Footnote 64 with the UK and the United States diminishing their roles as the most influential “lender” courts.Footnote 65 Around the same time, however, Yves Dezalay and Bryant Garth's work on legal globalization described the United States as “the leading exporter of rules” in the “governance of the state and economy.”Footnote 66 The United States led many efforts to promote U.S. legal models and train judges around the world.Footnote 67 More recently, Katharina Pistor has noted that “global capitalism as we know it . . . is built around two domestic legal systems, the laws of England and those of New York State.”Footnote 68

In the last two decades, scholars of transjudicial dialogue have focused on citation practices across courts and whether judicial networks in fact facilitate legal harmonization.Footnote 69 Most of this debate discusses constitutional or human rights law.Footnote 70 With a few exceptions, debates about citing foreign courts have ignored the presence of foreign judges on domestic courts.Footnote 71 The studies connecting conversations about judicial cross-citations and foreign judges have focused on public law.Footnote 72

The Hong Kong CFA's overseas judgesFootnote 73 have received greater scrutiny. These judges’ presence was intended to assure domestic and international constituencies, especially business, that Hong Kong would maintain its status as a leading commercial center after 1997.Footnote 74 Until recently, both the Hong Kong government and the pan-democratic opposition emphasized the presence of these judges as guaranteeing the rule of law and the Hong Kong judiciary's independence.Footnote 75 That consensus appears to be collapsing.Footnote 76

C. Traveling Adjudicators and International Commercial Dispute Resolution

International commercial arbitrators also travel extensively and provide a template for traveling judges. This Section discusses the rise of both kinds of traveling adjudicators.

1. International Commercial Arbitration

International commercial arbitrators adjudicate enormous numbers of disputes.Footnote 77 They are themselves one of many reasons commercial parties are said to prefer arbitration.Footnote 78 Parties often select arbitrators, from a list provided by an arbitral institution, for their “virtue,” subject matter expertise, or experience adjudicating complex disputes.Footnote 79 As private individuals, arbitrators represent a separation from any state;Footnote 80 some are chosen in part because they are not co-nationals of the parties, which may lend neutrality and legitimacy to the arbitration. Unless there is a global pandemic, international arbitrators travel extensively.

A 2015 study of international arbitrators found that the median arbitrator was a fifty-four-year-old male citizen of a developed state.Footnote 81 The field overall was “relatively homogenous,” with 15 to 20 percent of arbitrators from developing countries (depending on how that was defined). The study found 23 percent of arbitrators were U.S. nationals, while 9.6 percent were UK nationals.Footnote 82 The authors argued that greater diversity on several levels would help arbitration establish and maintain legitimacy in the eyes of the international community it serves.Footnote 83

2. The Rise of Commercial Courts and International Commercial Courts

Despite arbitration's popularity, many cross-border disputes are litigated in domestic courts. Some of those courts, like the Southern District of New York or the Supreme Court of Delaware, have broad jurisdiction over civil and criminal cases. Others, like the London Commercial Court or the New York Commercial Division, specialize in commercial disputes whether domestic or transnational. Starting in the 1990s, jurisdictions around the world began copying the London Commercial Court model of establishing specialized commercial court divisions.Footnote 84 The Cayman Islands and the BVI both have commercial divisions in this mold.

In the last two decades, jurisdictions have established new courts or chambers dedicated to international commercial disputes. These include special international commercial court divisions in Paris, Frankfurt, and Amsterdam; courts associated with special economic zones (SEZs) in Dubai, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Kazakhstan; and dedicated “international commercial courts” in Singapore and China.Footnote 85

Many of these new courts have adopted procedures or structures that mimic either the London Commercial Court and/or conventions in international arbitration, in an effort to create courts that provide the “best of both worlds.”Footnote 86 The SEZs’ courts, for example, all operate entirely in English, have procedural codes modeled on London's, and have either received English common law into the local SEZ's law or based their statutes on English common law and statutes. The DIFC's common law is “determined by the Courts of the DIFC from time to time drawing upon the common law of England and Wales and other common law jurisdictions as they see fit.”Footnote 87 In an echo of colonial era laws in places such as Hong Kong, English common law and equity apply in the ADGM “so far as it is applicable to the circumstances” of the ADGM.Footnote 88 The QIC's and AIFC's statutes largely reflect English law.Footnote 89 The SICC, a 2015-established division within an English language, common law judicial system, allows parties considerable autonomy to propose procedural rules, subject to court approval, mimicking the flexibility of arbitration.Footnote 90

Complex factors drive these efforts.Footnote 91 Some scholars explain the adoption of English law, common law procedure, English language, and other conventions of the London Commercial Court and arbitration as a “race to the top”—a competition between courts and arbitration to provide the best dispute resolution available.Footnote 92 Bookman has explored other motivating factors—including a desire to attract foreign direct investment or become a litigation destination like London.Footnote 93 King has questioned the premise of the “race to the top,” arguing instead that courts have incentives to offer procedure that sophisticated parties find familiar, but not necessarily “better.”Footnote 94 Familiar procedure can mean common law-style procedure because so many outside counsel are common law-trained lawyers.Footnote 95 The shared history of British influence and common law coordination under the JCPC, which persisted in most of the common law world (outside the United States) until a few decades ago, helped establish shared experience and expectations among common law lawyers, even in the face of local differences.Footnote 96

These studies have focused on the courts’ procedures and institutional structures. This study focuses on the judges.

II. Methodology

In studying traveling judges on courts that handle international commercial disputes, we faced two definitional challenges: which courts to count as “commercial” and which judges to include as “traveling.” This Part explains how we selected which courts to include in our study, how we defined “traveling judges,” how we chose which judges to include in the study, and how we collected the data.

A. Selecting the Courts

This Section describes how we defined the universe of courts to include in this study. Our list is likely both under- and over-inclusive of courts that have aspirations in international commercial law, but it can be a starting point for future research.Footnote 97

Many courts that are not titled “international commercial courts” or that have broad subject-matter jurisdiction nevertheless have significant international commercial caseloads, like the Southern District of New York. Some courts that specialize in commercial disputes, like the London Commercial Court and the New York Commercial Division, hear substantial numbers of cross-border (as well as domestic) disputes—and will hear disputes without any ties to the jurisdiction if the parties choose the court in their forum-selection clause.Footnote 98 Courts that are called “international commercial courts,” like the Singapore International Commercial Court, may allow domestic parties to self-designate their dispute as international.Footnote 99 Other courts that might be called “international commercial courts,” like the DIFC courts, have jurisdiction over disputes that are local to the SEZ and similar zones, in addition to allowing parties to opt in to jurisdiction.Footnote 100

To capture the universe of courts that have or aspire to have substantial cross-border commercial dockets, we examined courts that self-identified as such by joining the recently created SIFOCC.Footnote 101 In 2016, Lord Thomas, the former lord chief justice of England and Wales and a former judge on London's Commercial Court,Footnote 102 invited his counterparts around the world to create the SIFOCC.Footnote 103

SIFOCC membership is open to institutions from any jurisdiction “with an identifiable commercial court or with courts handling commercial disputes.”Footnote 104 Member courts all self-identify as courts that “hear and resolve domestic and/or international disputes over business and commerce.”Footnote 105 Membership thus provides a serviceable way to distinguish which courts consider themselves commercial and engage with foreign counterparts. The recent spate of specialized international commercial courts are all SIFOCC members.Footnote 106 Members also include domestic courts or divisions with large percentages of cross-border commercial cases, like the London Commercial Division, the Cayman Islands Financial Services Division (FSD), and the Supreme Court of Delaware.Footnote 107 Most are first instance courts, although some are appellate courts or high courts, which include both trial and appellate divisions.Footnote 108 Most SIFOCC member courts are common law courts, even if they are not located in common law host states.Footnote 109

SIFOCC membership is an imperfect measure of which courts are oriented toward commercial and cross-border disputes, but it provides a limiting principle and showcases the phenomenon. Whether a court has joined may be due to budget constraints or even happenstance.Footnote 110 SIFOCC's founders were from common law jurisdictions and had worked in the UK and British overseas territories, which may account for the particularly strong common law presence.Footnote 111 But focusing on SIFOCC members does seem to capture the universe of courts that proactively self-identify as cross-border dispute resolution fora. This approach is in some respects over-inclusive because it brings in the Supreme Court of The Gambia, which is better understood as a domestic apex court with some foreign judges than as a court focused on serving transnational commercial litigants,Footnote 112 and the non-commercial divisions of the ECSC, which likewise focus on domestic disputes. Thus, although we include them in the initial count for completeness,Footnote 113 we will largely exclude the Supreme Court of The Gambia and the ECSC's non-commercial divisions from the discussion in Parts III and IV.

Relying on SIFOCC leaves out certain courts.Footnote 114 For example, the SIFOCC screen excludes the Cayman Islands Court of Appeal and the Bermuda Supreme Court, both of which hear appeals from SIFOCC member courts and which supervise international corporate tax havens; it likewise excludes courts in Gibraltar, Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man. We did not include these courts because they had not joined SIFOCC. It appears that their inclusion would not have substantially altered our overall results or analysis. To the extent these courts have traveling judges, most appear to reflect the demographics documented here. One might also have included the JCPC, which exercises extraterritorial jurisdiction, but that is a sui generis institution, and its judges do not travel to hear cases.Footnote 115 In short, even if relying on SIFOCC is somewhat over- and under-inclusive, it remains a useful screen for identifying courts focused on cross-border commercial disputes.Footnote 116

Traditional studies of foreign judges often include the Hong Kong CFA and the ECSC, but usually not the other courts we have identified—perhaps because some are still new, relatively small, and sometimes subnational. Foreign judges are also found on apex courts of very small states, such as the Pacific Island states, Andorra, Monaco, or Lichtenstein.Footnote 117 While these states may hear some cross-border commercial disputes, we do not consider them because they are not centers for such disputes, as Hong Kong is, and their foreign judges are typically intended to fill benches where there are insufficient numbers of citizen judges, not to serve the needs of transnational litigants.Footnote 118

B. Classifying the Judges

Focusing on these commercial courts, we then examined their benches to determine which include traveling judges. We define “traveling judges” as those judges who, at the time of appointment, were not citizens of the host court's jurisdiction, did not permanently reside there, and did not have their primary legal career there. Courts that invite traveling judges do not require their judges to reside in the host jurisdiction before they accept the post. Traveling judges may have had some contact with the host court jurisdiction in their work as attorneys, but our definition excludes anyone who held government office, or for whom court or law firm bios or, failing that, news articles, indicate that they practiced as local lawyers. The barrister who “flies-in” regularly from London counts as traveling if appointed to the bench, but the UK born and English-trained head of the tax practice at a local firm would not.

Unlike most studies of “foreign” judges, we defined “traveling judges” by jurisdiction rather than purely by nationality.Footnote 119 This approach accounts for states with multiple jurisdictions. Thus, we may distinguish English barristers from Scottish advocates, Delaware judges from Nebraska ones, or Ontario lawyers from Quebec ones. We focus on the location of the judge's primary legal career, or her “home jurisdiction,” rather than nationality, which can raise complicated citizenship questions. Most traveling judges had prior legal careers concentrated in one home jurisdiction.Footnote 120 For judges who worked in multiple jurisdictions, we focused on the jurisdiction in which they worked prior to appointment as a traveling judge, where they worked the longest, and where they held government office.Footnote 121 If a judge at home in one jurisdiction traveled to sit on another jurisdiction's court and returned, we did not consider her to be a traveling judge when sitting on her home court.Footnote 122

C. Identifying Commercial Courts with Traveling Judges

By examining the judiciaries of SIFOCC member courts, we identified traveling judges on nine SIFOCC-member domestic courts or court systems in the Caribbean, the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Central Asia, that is, on 20 percent of SIFOCC member institutions.Footnote 123 These traveling judges appear on some of the most innovative new international commercial courtsFootnote 124 as well as some of the busiest jurisdictions in the Caribbean.Footnote 125

Those courts are:

D. Judge Census

We first collected publicly available biographical and demographic information on all judges for each of the SIFOCC members that employed traveling judges in June 2021.Footnote 126 We identified over 120 current and former traveling judges on the relevant courts, of which seventy-two were listed as active judges on June 1, 2021. If available, we recorded the judge's nationality, home jurisdiction, previous employment, race, gender, and whether they worked as an arbitrator, as well as dates of retirement and hiring.Footnote 127 Historical information was much more readily available for some jurisdictions than for others.Footnote 128 As a result, we focused on a snapshot of the courts in June 2021. The study aimed to identify who traveling judges are across a variety of metrics to aid the analysis in this Article and future studies.

E. Interviewing Judges and Court Personnel

To give greater context to the data and to understand the practical working of these courts, we also interviewed current and former judges on these courts and current and former court staff. Our aim was to speak with at least one, and ideally two or more, local judges, traveling judges, or staff from each court in the study. Most of our interviewees were traveling judges. As lawyers often rely on personal connections, we used snowball sampling and began by talking to existing contacts.Footnote 129 The interviews were thus not representative, but were helpful in interpreting publicly available sources. Moreover, the interviews allowed us to understand elements of court practice that are not easily available to the public, such as judicial pay structure and case assignment. We asked participants how they came to serve on these courts, why they agreed to serve, how cases were assigned, how much time they spend as a traveling judge on each court on which they serve, and what their responsibilities are.

We spoke to twenty-eight judges and court personnel or others familiar with the working of these courts. We offered participants the opportunity to be anonymized or speak under Chatham House rules. We are unable to report totals for each court due to confidentiality concerns, but we can report that final interview numbers provided lopsided representation, favoring some courts more than others.

III. Introducing Traveling Judges

This Part lays out who traveling judges were as of June 1, 2021. It also reports on how they are hired, fired, and paid, and what they do—both as judges and when they are not judging. Traveling judges on commercial courts are an overwhelmingly common law phenomenon. Almost all the traveling judges in this study spent their careers in a common law jurisdiction; all but one traveling judge holds at least one law degree from a common law country. A majority practiced in England and Wales and an even larger number studied law in the UK. Judges from outside the UK tend to travel within their own regions—but their numbers are typically too low to draw firm conclusions about their patterns of circulation. English judges, however, are everywhere. The result of this heavy focus on hiring English judges is that the demographics of traveling judges resemble the English judiciary in race and gender. There are, however, some significant differences if one focuses on individual courts or specific regions.

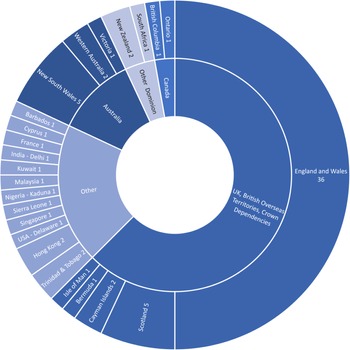

We include traveling judges throughout the ECSC as well as those on the Supreme Court of The Gambia in our initial count (Figure 1) based on their SIFOCC membership. But these courts do not fit the profile of international-business-focused courts. We also have the least amount of information about the judges on these two courts, apart from the BVI Commercial Division. In most of our discussion, we exclude the Supreme Court of The Gambia and the ECSC, except for the BVI Commercial Division, the ECSC division with the most international commercial cases.

Figure 1. Traveling Judges by Home Jurisdiction—June 2021

These judges tend to be invited by well-respected acquaintances or colleagues; they usually serve for renewable terms of a few years; and they serve on good behavior, often removable by the authority that hired them. With some exceptions, their appointments are part-time. They are often also arbitrators or serve in other positions.

A. Who Travels

This Section reports our data on who traveling judges are as of June 1, 2021, in terms of their home jurisdiction, education, prior careers, race, and gender. We also note reasonable inferences about the judges’ average age.

1. Home Jurisdiction, Education, and Judicial Experience

Home jurisdiction

Far and away the most common home jurisdiction was England and Wales (50 percent), followed distantly by Scotland (7 percent). Australian jurisdictions came in next with New South Wales (7 percent), Western Australia (3 percent), and Victoria (1 percent). A majority of judges (60 percent) were UK nationals. A supermajority (75 percent) was from the UK or a former dominion colony (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, or South Africa). Figure 1 below shows the home jurisdiction of all the traveling judges on commercial courts as of June 1, 2021. A chart listing all home jurisdictions appears as Appendix 1 at the end of this Article.

Figure 1 shows that traveling judges are a primarily common law phenomenon. The only home jurisdiction listed with a purely civil law tradition is France, the home jurisdiction of Dominique Hascher of the SICC.Footnote 130 Six traveling judges are from countries with a mixed legal tradition.Footnote 131 Still, the prevalence of common law judges is clear. In Hong Kong, the Caribbean jurisdictions, and The Gambia, only judges from common law or Commonwealth countries may serve.Footnote 132 Figure 1 also suggests a break with colonial patterns in judicial hiring. Roughly twenty-five percent of traveling judges are from home jurisdictions that are not part of the UK or its former Dominion colonies.

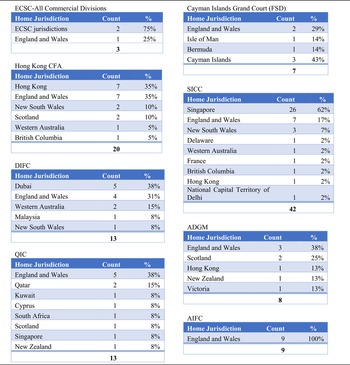

Breaking out the individual SIFOCC member institutions demonstrates a difference between the ECSC, the Supreme Court of The Gambia, and the rest of the courts. The ECSC and the Supreme Court of The Gambia have the lowest percentages of UK traveling judges and the most regionally representative benches of traveling judges (to the best of our knowledge, both traveling judges in The Gambia were from West Africa). They are also less internationally oriented than the remaining courts, which are designed specifically for cross-border cases or which are in jurisdictions oriented around providing international legal services.

In a sense, all judges on the ECSC are traveling judges—trial judges do not sit in the same jurisdiction in which they practiced and the appellate court travels to member jurisdictions.Footnote 133 It is not unusual for lawyers to circulate within the Eastern Caribbean. Therefore, we counted as “traveling” only those ECSC judges who came from outside the Eastern Caribbean.

The ECSC has two commercial divisions, the BVI Commercial Division and the St. Lucia Commercial Division. In June 2021, the St. Lucia Commercial Division judge was from an ECSC member jurisdiction (i.e., that division had no traveling judges) and historically that division had a less international caseload.Footnote 134 Since it was established in 2009, the BVI Commercial Division has been staffed primarily by traveling judges who have resided in the BVI during their terms, some of which were scheduled for only a few months. These traveling judges often had prior practice experience in the region—BVI lawyers often hire London barristers for significant cases in the BVI—but dividing judges as we did still allowed us to distinguish those whose careers were focused within the Eastern Caribbean. As of June 2021, the BVI court had two judges: one English judge and one judge who began his career in England, but subsequently moved to Anguilla, an ECSC jurisdiction. The BVI Commercial Division fits the profile of an internationally oriented commercial court, but the rest of the ECSC does not. We therefore focus on the BVI Commercial Division in the rest of our discussion.

Based on the information we were able to obtain, the Supreme Court of The Gambia recently had two traveling judges, both from other common law jurisdictions in the region: Nigeria and Sierra Leone. We were not able to verify that both held office in June 2021. Moreover, the Supreme Court of The Gambia seems to be internally focused in its work and court officials have been prioritizing hiring Gambian judges at all levels. The Gambian Supreme Court offers valuable insights on the politics and ethics of traveling judicial service, but it is less relevant to a discussion of efforts to appeal to foreign commercial parties in 2021.

If one focuses only on the courts in our study most oriented to international commerce,Footnote 135 the traveling judges look more like their colonial antecedents. Eighty-three percent are from the UK and long-term Dominions (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa). The AIFC courts in Kazakhstan have 100 percent English judges. The rest of our discussion will focus primarily on the judges in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Traveling Judges by Home Jurisdiction Excluding Non-Commercial ECSC and The Gambia—June 2021

Education

English law influence is even more apparent when one looks at the traveling judges’ education. Of the judges included in Figure 2, forty-six (73 percent) studied law in the United Kingdom. Most judges received their first degrees in the country in which they then spent their careers (their home jurisdiction).Footnote 136 Judges who did not do so mostly studied in the UK (four judges overall).Footnote 137 About a quarter of traveling judges (seventeen) held a graduate degree in law, all of which were from common law countries—predominantly the United Kingdom and United States.Footnote 138

Figure 3. Country of Legal Education of Traveling Judges Excluding Non-Commercial ECSC and The Gambia—June 2021

Prior judicial experience

Most traveling judges have retired from serving as judges in their home jurisdictions. Fifty-four (86 percent) held initial judicial appointments in their home jurisdictions.Footnote 139 Twenty-nine sat on apex courts (46 percent).Footnote 140 Of those who had never sat on an apex court, four had experience as a judge on a commercial court, such as the London Commercial Court, or on a business law related court division, such as being the judge in charge of a construction list. Eighteen traveling judges (29 percent) had experience as a traveling judge on more than one court, whether concurrently with their 2021 position or prior to being hired by the 2021 court.

2. Race and Gender (and Age)

Most traveling judges, both in 2021 and historically, have been white and male, reflecting the demographics of the English judiciary.Footnote 141 As traveling judges tend to be at the end of their careers, relatively recent demographic changes in the UK bar would take time to appear in our data.

Significant differences exist in the demographics of courts in different regions. In part these differences reflect different ratios of traveling to local judges and in part they reflect regional variations in the demographics of traveling judges. They may also reflect conscious choices to localize, or regionalize, the judiciary.Footnote 142

Race

Across all the courts, as of June 2021, fifty-seven of the traveling judges we identified were white; seven were Black. The numbers then become quite small—four judges were South Asian, two were Arab, and two were East Asian. Based on the Figure 2 data (i.e., excluding the non-commercial ECSC and the Supreme Court of The Gambia), there were fifty-five white judges and only one Black judge. Three were South Asian, two were Arab, and two were East Asian.

Gender

We determined gender identity based on the names and pronouns used in judges’ biographies. Of all judges sitting in June 2021, sixty-one judges identified as men; eleven as women.Footnote 143 In our smaller Figure 2 set, fifty-five identified as men and eight as women. With the exception of the BVI Commercial Division, every court or division had at least one woman judge, although not necessarily one woman traveling judge.Footnote 144

Age

We were not able to collect comprehensive information on traveling judges’ ages, but inferences can be drawn from the fact that that three-quarters of traveling judges in this study are retired judges in their home jurisdictions. Prior to June 2021, the UK's retirement age was seventy.

3. Regional and Court Differences

Traveling vs. local judges

Ratios of traveling to local judges varied substantially among courts (Appendix, Table 3). The Hong Kong CFA had three permanent local judges and four non-permanent local judges, but thirteen traveling judges. The Cayman Islands Grand Court FSD had three local judges out of a bench of seven.Footnote 145 The oil state SEZs—in Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Qatar, and Kazakhstan—also had high proportions of traveling judges. The AIFC was the most extreme case. All nine AIFC judges were traveling judges, and all were white UK citizens who spent their prior legal careers in practice or in the judiciary of England and Wales.Footnote 146 The ADGM court likewise had no local judges. Five judges were from the United Kingdom, one was a Hong Kong permanent resident (although not a Chinese national), one was a New Zealander, and one was Australian. On the QIC, only two judges were Qatari. The DIFC, however, had several local judges and had been involved in developing local judicial talent—identifying candidates and helping them to study in the UK as well as training them internally.

The ECSC (if one includes the entire court) and SICC looked very different, with a larger complement of local judges, different racial demographics, and greater gender balance. These courts did not rely on English judges as much. Twenty-eight of the thirty-six judges on the ECSC in June 2021 were from Eastern Caribbean jurisdictions. The eight traveling judges’ primary careers were in a variety of locations—with the majority coming from other (non-ECSC) countries in the Caribbean. Since its inception, the BVI Commercial Division has had only one or two judges at a time. The two judges serving full terms in 2021 were both white men, with home jurisdictions of England and Wales and Anguilla.

In June 2021, the SICC had the largest roster of the courts in this study, with forty-two active judges. The judges included thirty-three men and nine women. Twenty-six (62 percent) were Singaporean and sixteen (38 percent) were “international.” A majority of the court's judges were East Asian (55 percent). Of the international judges, one was East Asian and one was South Asian; the rest were white.

B. How Traveling Judges Are Hired, Removed, and Paid

Publicly available information reveals varying appointment structures. For example, permanent and non-permanent judges on the Hong Kong CFA are appointed by the chief executive on the recommendation of an independent commission (Judicial Committee) composed of local judges, persons from the legal profession, and eminent persons from other sectors.Footnote 147 Some news outlets report that appointments now require support from the Central Government in Beijing.Footnote 148 On the ECSC, the Crown appoints judges via the Judicial and Legal Services Commission.Footnote 149 In Singapore, judges are appointed by the president if she concurs with the advice of the prime minister, who in turn must consult with the chief justice.Footnote 150 In Dubai, DIFC judges are appointed by the ruler's decree.Footnote 151

With the exception of the members of the UK Supreme Court then sitting on the CFA, traveling judges applied or were invited in their individual capacities rather than as representatives of their home courts or countries.Footnote 152 The Cayman Islands Grand Court and the ECSC have open public competitions, although suitable candidates might be encouraged to apply.Footnote 153 The remainder of the courts do not seem to take applications—one is invited.Footnote 154 The invitation was usually extended by an acquaintance who had some affiliation with or connection to the hiring court.Footnote 155 This approach seems to follow the historical English and colonial norm of appointing judges with a “tap on the shoulder,” rather than the more modern trend in Commonwealth countries of appointing judges through an independent judicial service commission. Only one traveling judge we interviewed applied without prompting and had no prior connection to the court.Footnote 156 We cannot determine how many judges have declined such invitations, but those that declined reportedly cited an otherwise overbooked schedule, lack of interest in travel, or conflicts of interest with other work (such as being a partner in a U.S. law firm).Footnote 157 Judges cited interest in the work and desire to advance the rule of law as reasons for taking the job.Footnote 158

Salary information for traveling judges was typically not readily available, but our interviews provided information about pay structure. On the ECSC and in the Cayman Islands, judges receive fixed salaries. The BVI Commercial Division Judges receive a higher salary than other judges.Footnote 159 On the Hong Kong CFA, the SICC, and the AIFC, ADGM, and DIFC courts, judges are compensated for their time hearing cases and preparing opinions (for example with a per diem or hourly sitting fee).Footnote 160 Unlike some foreign judges on constitutional courts, who are paid by international organizations,Footnote 161 the hiring courts pay these traveling judges.

We found little publicly available information about termination of judicial appointments.Footnote 162 Most courts appoint judges for renewable terms of three or five years. In the Eastern Caribbean, appointments may be shorter (sometimes a matter of months), but full-time positions involve a three-year term. Traveling judges in Hong Kong have three-year terms that may be renewed by the chief executive based on the chief justice's recommendation.Footnote 163 The ADGM courts’ traveling judges also have three-year terms, based on renewable contracts. The DIFC court has made temporary appointments; regular appointments are for specified periods of no more than three years, but the appointments may be renewed.Footnote 164 Judges in the Qatar and Kazakhstan courts are hired for five-year renewable terms.Footnote 165 International judges on the SICC are typically appointed for a three-year period but may also be appointed for the purpose of hearing specific cases.Footnote 166 This regime contrasts with longer terms for local judges. Most of the courts have a retirement age between sixty-five and seventy-five, but those limits may be ignored.Footnote 167

Most courts have some guarantee of judicial independence in their founding documents and a provision that they shall hold office “during good behaviour,” or similar.Footnote 168

C. What Traveling Judges Do

With the exception of some courts in the Caribbean, serving as a traveling judge is not a full-time job. Interviews suggest that part-time judges on some courts spend up to a quarter of their working time on court duties. In an appellate position, this time may be considerably less.Footnote 169 At least one traveling judge sits as part of any HK CFA panel or SICC appellate panel, but both courts have multiple traveling judges to choose from.Footnote 170 Traveling judges’ work closely resembles that of other common law judges, such as hearing motions, presiding at trial, and writing opinions. Indeed, none of the judges interviewed reported receiving any required judicial training upon their appointment to a traveling position, although some courts have regular training for all judges.Footnote 171

In other ways, serving on these courts can resemble being an arbitrator on an arbitration provider's list. Like arbitration, many of these courts have subject-matter jurisdiction that is effectively limited to commercial cases and the parties are often before the court by consent. Like arbitration, many of the specialized courts with traveling judges assign judges based on their fit with a particular dispute (as well as availability).

Several judges had multiple simultaneous appointments.Footnote 172 Thirteen judges in our study held simultaneous appointments on two courts; two held appointments on three courts (for example, on the Hong Kong CFA, the SICC, and the DIFC courts). ADGM court appointments are part-time, but the court does not allow second judicial appointments.

As traveling judge positions are usually not full-time, judges often hold other roles. A majority (70 percent) of traveling judges identified themselves on firm or personal websites as arbitrators or were present on arbitration provider lists.Footnote 173 Many continue arbitral practice while holding the part-time judicial appointments described above.Footnote 174 Even with full-time appointments, a traveling judge might be sought out specifically for their expertise in a specific area of law and would be able to go back to practice in that area when the judicial appointment ends.Footnote 175 In contrast to others, however, full-time judges in the Caribbean do not have time for outside work and often live in the jurisdiction during their appointments.

IV. Explaining Traveling Judges

This Part analyzes which courts hire traveling judges, why they hire them, what circumstances in home jurisdictions make traveling attractive or easier for prospective traveling judges, and why traveling judges travel.Footnote 176

A. Who Invites Traveling Judges?

The collection of commercial courts that hire traveling judges is diverse along many dimensions. To understand the potential global influence and implications of the modern phenomenon of traveling judges, it is important to understand their similarities as well as their differences. These courts are English-language, common law courts often modeled on the London Commercial Court to varying degrees. The courts vary in terms of their status within their host judicial system (apex court, high court, trial court) and in the breadth of their subject-matter jurisdiction. Almost all the host countries have a history of British colonial influence, either as protectorates or colonies. These states are, again to varying degrees, interested in making their judicial systems attractive to foreign potential litigants and a global audience; hiring jurisdictions are usually established or aspiring financial or legal hubs, tax havens, or destinations for foreign direct investment. Host states of these courts are often small jurisdictions, either non-democracies or non- self-governing territories.Footnote 177

1. Commercial Courts that Hire Traveling Judges

This Subsection highlights commonalities and distinctions among the courts that hire traveling judges. To recap, our study of SIFOCC members found nine with traveling judges. Three courts handle both criminal and civil cases: the Supreme Court of The Gambia, the ECSC, and the Hong Kong CFA. As discussed in Part III, we exclude the Supreme Court of The Gambia and the ECSC with the exception of the BVI Commercial Division from our discussion, but include the Hong Kong CFA. Two members are commercial trial divisions in British Overseas Territories (BVI and Cayman Islands); five are the common law court systems of SEZs in oil producing states in the Middle East and Kazakhstan; and one—the SICC—has subject matter limited to disputes that are both commercial and international.

English, common law courts

All of these courts operate in English, even if English is not an official language of their host country. They all self-identify as common law courts. They all have procedural rules similar to, if not modeled after, the rules that operate in English courts. They apply substantive law often based on English common law and commercial statutes. This choice is perhaps unremarkable for the common law jurisdictions in the Caribbean, The Gambia, Hong Kong, and Singapore, but more surprising in the oil states, which do not otherwise have common law judiciaries.

Accommodating traveling judges

These courts include benches composed of either all traveling judges (ADGM, AIFC) or of a mix of traveling and local judges (in Singapore, the QFC, DIFC, BVI, Cayman Islands). The BVI and Caymans divisions are commercial divisions of busy, longstanding court systems. Only the BVI requires judges to live in the jurisdiction when they serve. The judges’ terms can range from a few weeks to several years.Footnote 178 Some courts allow judges from any home jurisdictions,Footnote 179 others limit traveling judges to those from other common law jurisdictions,Footnote 180 or a subset of common law jurisdictions, like the Commonwealth.Footnote 181 All except the BVI allow judges to fly-in to hear cases or to use video and teleconferencing. The latter practice became pervasive during the COVID-19 pandemic.

London as model

Almost all the courts were modeled to different degrees on English courts. The four SEZ court systems all adopted a mixture of procedures from the London Commercial Court and those associated with international commercial arbitration (IBA Rules).Footnote 182 These courts are not secretive about their intention to provide London-style commercial dispute resolution—through courts, arbitration, and mediation services—or about their belief that judges are an important part of this mission. One judge (who sits elsewhere but has practiced in the Middle East) describes them, accurately, as aspiring to be “little Englands.”Footnote 183 The commercial focus of the SICC likewise was inspired by the London Commercial Court.Footnote 184 The commercial divisions in the Caribbean were likewise modeled on the London Commercial Court.

Relationship to broader judicial system

As noted, these courts may be trial level courts, high courts (trial and appellate), or apex courts. Some, like the Cayman Islands FSD, are part of a greater judicial infrastructure of a jurisdiction that relies on traveling judges throughout the judiciary.Footnote 185 Others, like the SICC, are the only divisions of their judiciaries that employ traveling judges.Footnote 186

The SEZs have court systems primarily staffed by traveling judges, but they are surrounded geographically (and legally and politically) by a domestic court system with domestic judges. There is documented jurisdictional competition between the DIFC and the “onshore” Dubai courts, for example, that showcases the potential tension between traveling-judge-dominated SEZ courts and their surrounding domestic courts.Footnote 187 Officials at the courts in the Kazakhstan and Abu Dhabi SEZs report working to build stronger relationships with the local judiciary to avoid similar conflicts.

2. History of British Influence

As noted at the outset, all but one host jurisdiction (Kazakhstan) has a history of direct or indirect British rule. Some hiring jurisdictions have a common law legal system as a result of this history. In the Middle East, this history provides experience with consular courts, designed to be used by foreigners for limited kinds of cases, during the time of British influence. The innovation of a separate common law legal system aimed at foreign investors today seems less surprising considering that history.

The history of the Hong Kong CFA provides the clearest bridge to today's traveling judges phenomenon.Footnote 188 At the 1997 handover of sovereignty, the PRC committed to maintaining Hong Kong's existing economic and legal systems for fifty years.Footnote 189 Placing foreign judges on the CFA helped demonstrate that commitment and stem capital flight.Footnote 190 In the years that followed, officials and both traveling and local judges on the CFA presented Hong Kong as a bastion of the rule of law within China—at least insofar as commercial interests were concerned.Footnote 191 That once broad consensus within the Hong Kong legal profession has now broken down.Footnote 192

This history alone does not explain traveling judges. Many new commercial court divisions—for example, those in the Netherlands, France, Germany, Pakistan, India, and throughout the United States—have relied entirely on local judges. Just as colonial history may inform some jurisdictions’ efforts to build on the English model or even transplant it, other jurisdictions may reject such options because that history makes the public concerned about loss of sovereignty or about foreign influence. Kazakhstan, moreover, provides a counterexample of a state with traveling judges—indeed with an entirely British bench—without a history of British colonial control. History, however, can combine with other political forces, local goals, and investor preferences, to drive host governments to see hiring traveling judges as a strategy that advances their interests.

3. Investment-Friendly and Forum-Selling Commercial Courts

Most of the commercial courts that hire traveling judges are part of the recent trend of designing courts to cater to commercial disputes.Footnote 193 They are in a sense international “forum sellers,” seeking to make their courts attractive not only to local parties but to a broader commercial community to support the jurisdictions as legal hubs, tax havens, and destinations for foreign direct investment.Footnote 194 Commercial courts are important to these jurisdictions in part because they are believed to attract certain types of foreign capital—including but not limited to legal business.Footnote 195

These courts may appeal to different kinds of investors or litigants. The SEZs’ courts are explicitly oriented around foreign investment. The Dubai government wanted “a new, global judiciary that would be functional and be seen as legitimate by the commercial-investor world.”Footnote 196 In the late 1990s and early 2000s, it hired two British law firms, Allen & Overy and Clifford Chance, to advise it on attracting foreign investors. It built the new DIFC courts around their recommendations.Footnote 197 The DIFC courts were then a model for Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Kazakhstan.Footnote 198 These governments established SEZs that operate in English and follow the common law as a means of attracting foreign direct investment, often in response to specific requests from investors, who indicated that they wanted to invest in the region but also would prefer to do so with more familiar judicial structures in place.Footnote 199 Singapore has different goals, positioning its courts to hear a wide variety of commercial disputes from around the region.Footnote 200 The Caribbean courts cover tax haven jurisdictions that cater to cross-border commercial disputes. The Cayman Islands FSD and the BVI Commercial Division hear many important and high value corporate cases, especially in international insolvency. These jurisdictions regularly collaborate with or hear cases that parallel proceedings in other important commercial jurisdictions, like New York, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

4. Small States, Sub-national Jurisdictions, and Political Limitations

Both size and government structure facilitate hiring traveling judges as well as other kinds of court innovation.Footnote 201 Hiring courts are all in relatively small states or subnational jurisdictions. In some jurisdictions, like those in Kazakhstan and Dubai, creating these courts required a constitutional amendment, but such requirements were quickly met as neither regime is an electoral democracy.Footnote 202 Jurisdictions without contested elections are less likely to face backlash for creating different rules for foreign companies or hiring non-locals as judges that has sometimes accompanied these efforts.

The importance of courts’ legitimacy before a local constituency, and other aspects of the local political economy can impede initiatives to hire foreign judges. Belgium, for example, considered creating a “Brussels International Business Court” that would have included an international panel of judges, but the proposal was defeated in Parliament in part due to arguments that it was a “caviar court,” catering too heavily to litigants with high-value disputes rather than addressing wider access to justice concerns.Footnote 203 Concern about legislative opposition has led the Supreme Court of the Bahamas to reduce the number of traveling judges it hires despite court leadership's desire to attract international commercial cases.Footnote 204

For the most part, the hiring governments in our study are unlikely to face local political backlash for internationalizing the commercial judiciary. First, local constituencies may be less concerned about courts with jurisdiction limited to commercial disputes primarily involving foreigners.Footnote 205 Second, several jurisdictions in our study either do not have elections, or are regimes with uninterrupted, single-party rule or only partial elections in which opposition participation is limited.Footnote 206 They do not face the same constraints on hiring.

B. Why Hire Traveling Judges?

Having identified the kind of courts that hire traveling judges, we next consider why these courts hire traveling judges, informed by our findings on who traveling judges are. In many jurisdictions, there is a strong default presumption that judges will be locals. This presumption holds even with respect to common law commercial courts,Footnote 207 such as in India, which authorized special commercial court divisions in 2015,Footnote 208 and Australia, which has considered establishing a national international commercial court.Footnote 209 Likewise, not all commercial courts in non-common law jurisdictions use foreign judges, even when offering English language options. All the judges of the Paris international commercial court divisions are French nationals drawn from within the French judiciary.Footnote 210 The Chinese International Commercial Courts have an advisory board of foreign legal experts, but the judges are all Chinese.Footnote 211 The local international commercial courts in Beijing and Suzhou also have only Chinese judges.Footnote 212

We therefore assess three standard explanations for foreign judges—lack of local capacity, desire for expertise, and reputation building—and find that they offer some, but incomplete, explanations for these traveling judges on commercial courts. Beyond expertise, for example, these judges also bring elite status. We then offer an additional explanation: traveling judges offer hiring jurisdictions a mechanism for transplanting an adapted version of a successful commercial court, like the London Commercial Court. These four explanations draw together similar themes among the different courts, although they are not intended to be exclusive and they should be re-evaluated over time in future research.

1. Lack of Local Judges

Scholars of foreign judges often cite a lack of local judges as an explanation for foreign or traveling judges.Footnote 213 Capacity issues may exist at some points in time for some jurisdictions, but lack of capacity does not require hiring former members of the UK Supreme Court.

It is intuitively appealing to explain traveling judges as filling a need created by a lack of local judges. Many traveling-judge host jurisdictions are geographically and demographically small. In such jurisdictions, there may be few local judges who have experience with complex commercial dispute resolution.Footnote 214

An underfunding of judicial salaries—not a shortage of lawyers—may create the need for traveling judges.Footnote 215 Underfunded judicial salaries can discourage lawyers from serving as judges, especially when they can otherwise have lucrative careers in commercial law. In Hong Kong, where top barristers bill at high rates in comparison with judicial pay, the judiciary has a perennial recruitment problem.Footnote 216 Similar considerations may be at issue in Caribbean jurisdictions, where lawyers—especially those that specialize in areas like tax, corporate law, or insurance—can have considerably more lucrative careers than judges. If Singapore, by contrast, is looking to build a court with the capacity to hear disputes from around the globe, or at least throughout the region, it may need to hire traveling judges to accommodate the quantity and types of cases it would like to see in the future.Footnote 217

In the SEZs, traveling judges make up for a lack of local common law expertise, but that provides a satisfactory explanation only if one presupposes the necessity of a common law court in these non-common law states. There may be local judges qualified to hear complex disputes, but these jurisdictions displace them (or, in the case of the DIFC and Qatar, supplement them) with traveling judges.

2. Expertise and Elite Status

Foreign judges are often hired for their expertise,Footnote 218 and traveling judges certainly bring relevant experience, but they also bring elite status. Today's traveling judges on commercial courts tend to be successful, retired judges from their home jurisdictions, often having served on apex courts or other domestic courts that specialize in commercial disputes. Common law judges typically have experience as practicing lawyers. Traveling judges bring expertise in their home jurisdiction's law, for example English or Australian law, which they can easily apply in jurisdictions where local law closely resembles English law or in cases where the parties selected English law.Footnote 219 They often bring expertise in particular areas of interest, such as construction or intellectual property, or extensive case-management skills honed while serving on a well-known court. It is no coincidence, for example, that the first U.S. judge on the SICC was a former chief justice of Delaware, and the second is a Delaware federal bankruptcy judge with expertise in cross-border insolvency.Footnote 220

Traveling judges also come from home jurisdictions where judges, especially members of apex and specialized courts, are members of the legal elite. Traveling judges tend to have qualifications far beyond a requisite number of years in practice or even as a judge.Footnote 221 Again, the statistics vary by court. The BVI Commercial Division, and the ECSC as a whole, have no former apex court justices. In contrast, all thirteen traveling judges on the Hong Kong CFA were from apex courts and seven had been presiding judges (known in the United States as chief judges).Footnote 222 Dubai has a policy of hiring only former presiding judges of apex courts to be presiding judges for the DIFC; the QIC's presidents have consistently been former lord chief justices of England and Wales.Footnote 223 In this way, today's traveling judges contrast sharply with colonial traveling judges, who tended to be “‘also-rans’ among English, Irish, and Scottish barristers or advocates.”Footnote 224 Where colonial judges were criticized for their ignorance of the local legal system and general lack of ability,Footnote 225 today's traveling judges are prized for their legal expertise and are highly accomplished.

In general, traveling judges’ common law and English-language legal educations enable them to serve as judges on hiring courts with a shared language and shared understanding of how to approach the law. Their expertise thus appears easily transferable to the traveling judge context, and any lack of familiarity with local law is often excused by the court's commercial focus. Judges report, however, that they may find more local differences and challenges as they confront the ways in which local law differs from English common law or in which local culture and politics differ from those they may be familiar with from their home jurisdictions.

3. Reputation Building: Traveling Judges as Separate from the Host State

Foreign judges are sometimes said to enhance the international reputation of the host state. Traveling judges’ experience, expertise, and elite status serve this function. Like foreign judges in other contexts, traveling judges on commercial courts are also valuable because they are not from the hiring state. They are not involved in the politics of the hiring state. Having built their careers and reputations in their home jurisdictions, they appear unbeholden to the host government for their livelihoods or their careers. Their separateness, as well as their elite status, reputations, and “virtue,” are intended to reassure foreign investors who may not understand or trust the hiring state. Judges’ presence is intended to be seen as an endorsement of the hiring jurisdiction and its rule(s) of law. Thus, they may build the institutional reputation of the court, and by association and sometimes by disassociation, of the host state.Footnote 226

Traveling judges complement the hiring jurisdictions’ reputations in different ways. To varying degrees, hiring authorities seek to signal to the international commercial community that their courts are efficient, non-corrupt, have English common law expertise, follow the rule of law, or are independent from the state.Footnote 227 Traveling judges are helpful in part by virtue of who they are: foreign judges, most of whom have stellar reputations on all these grounds.

On the other hand, some features of traveling judges’ positions raise questions about judicial independence. Whereas life or long-term tenure is sometimes considered a key component of judicial independence,Footnote 228 many traveling judges have short-term, renewable contracts. In theory, traveling judges could easily lose their jobs, or not have cases assigned to them, if the host state did not like how they were performing their judicial duties.Footnote 229

Concerns about independence raised by these structural features, however, might be muted when it comes to retired judges who may already be financially comfortable from their former careers or their concurrent careers as arbitrators. Most judges in our study report that they do not rely financially on judicial work.Footnote 230

Thus, the signature guarantee of independence is the judges themselves. Their reputations precede them. They recruit acquaintances with similar reputations, who rely in part on assurances of the judge who invited them or because a well-respected colleague has agreed to serve on the court.Footnote 231 They assert that they, and their colleagues, would resign if government officials were to interfere directly in case outcomes.Footnote 232 This background provides considerable returns for the reputation of the courts on which they sit. As one judge put it: “In the end, as we know throughout the world, it all depends on the people you get and the choice of people who are coming into the judiciary.”Footnote 233

4. Transplant as Shortcut

The traveling judges in our study bring several advantages, including experience, expertise, elite status, and separation from the host state. They also provide a mechanism for transplanting the success and reputation of the London Commercial Court or the New South Wales Commercial Division in Sydney.Footnote 234 English common law “is still the most sought-after law for transnational commerce,”Footnote 235 and English courts and judges are central to the law's appeal.Footnote 236 The London Commercial Court “has been described as the paradigm for the new international commercial courts, which are said to have been inspired in part by its success,”Footnote 237 although these courts all differ from the London court in various nuances and adaptations to local circumstances.Footnote 238 The London court is seen as “contributing to the success of London as an international commercial and financial centre that has led to its emulation.”Footnote 239 Striving for similar success, jurisdictions with traveling judges not only cater to parties’ preferences by recognizing their autonomy to choose their forum and the law that governs their contracts, but also replicate these private ordering preferences through the structure and personnel of their courts.Footnote 240

One might assume a court focusing on transnational commercial disputes would seek out an international roster of judges, or that a diverse bench could attract parties from around the world.Footnote 241 Our study does not support these hypotheses. Singapore's court comes the closest to having a broadly multinational bench, but it does not have a balance of civil and common law traditions. It originally had three judges from civil law jurisdictions, and in 2022, it will have two. The Qatar court is also relatively more diverse, with individual judges from Kuwait and other hybrid jurisdictions in addition to many English judges and one Qatari judge. Although the UAE jurisdictions do not restrict hiring to common law lawyers, they have no traveling judges from non-common law jurisdictions.Footnote 242 On the ADGM court, all the judges are UK, Australian, or New Zealand citizens, including one who is a retired Hong Kong judge.

Instead of internationalism, these traveling judges provide their hiring jurisdictions with a sort of transplantation shortcut for replicating a famously successful and well-regarded court and its legal system, familiar to the general counsel of the companies these jurisdictions are trying to attract.Footnote 243 It becomes easier to credibly assert that parties will get the same justice they are used to in London when the same people are sitting on the court, especially in non-common law jurisdictions. Those courts with entirely or mostly English benches seem to be replicating an English court. The oil states did not previously have common law legal systems; they chose English law for their SEZs after consulting with English law firms who represent the investors they hoped to attract.Footnote 244 Their courts model their founding statutes and rules of procedure on English law as well.