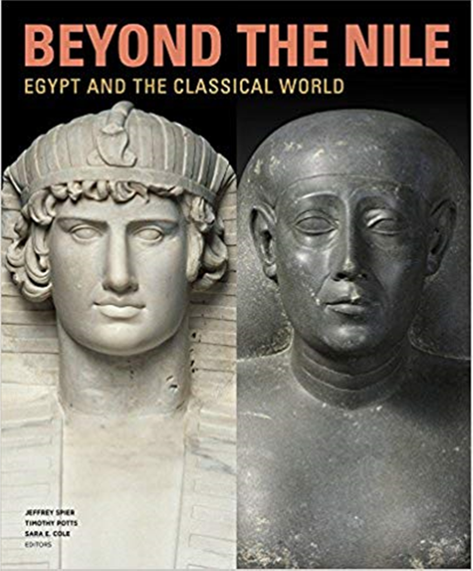

This is the catalogue of the eponymous exhibition presented at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles in 2018. It is a weighty volume, packed, as is usual with Getty Museum publications, with over 200 high-quality, large-scale, full-colour photographs of exhibits drawn from the Museum's own collection and from museums from around the world. It is a scholarly work, but written for the intelligent audience and is accessible to the sixth-form student. The book aims to investigate the extent and nature of relations between the ancient cultures of the Mediterranean and the Near East and is the first of what is intended to be a series to include Persia, Mesopotamia, Anatolia and others.

The book contains chapters on The Bronze Age (2000-1100BC), The Greeks Return to Egypt (700-332BC), Ptolemaic Egypt (332-30BC) and The Roman Empire (30BC-AD300). Each chapter follows a similar format: a map, a number of short articles on artistic, religious and political themes written by specialists in their field (lavishly illustrated), and an illustrated catalogue of objects. The book concludes with a chronology, bibliography and index.

For the teacher in a UK school, this book has much to commend it. There are several places where material is of relevance to currently-taught and assessed Classics courses. I choose four to detail below.

The Coming of Alexander and Egypt Under Ptolemaic Rule starts with a brief historical recap of the conquest of Egypt by Alexander and the division of his empire into territories held by his generals. A discussion of the governance of Egypt takes in how the Ptolemies exercised supposedly divine power, and used war and cultural propaganda to maintain and develop their ambitions in the Mediterranean. The section on agriculture, land organisation and the economy is clearly described, and takes in the development of the City of Alexandria and the construction of the Lighthouse at Alexandria: the section cautions against original readings of the ‘success’ of the central ‘despotic’ model of governance: evidence suggests that inconsistency in the application of regulations frequently led to failures in the organisation of the economy, for example.

Contact points: Alexandria, a Hellenistic Capital in Egypt starts with the Egyptian prophetic text The Oracle of the Potter (116BC?) and how it depicts the fraught relationship between Alexandria and the rest of Egypt. The section explores how much Alexandria was considered part of Egypt or separate from it (a construct more familiar in the Roman period than that discussed here). The City of Alexandria takes centre stage. How much was the city a mixture of Greek and Egyptian approaches to town-planning? How Greek were the types of buildings within the walls? Where did the population of the huge new city come from? What was the effect of the mingling of Greek and Egyptian populations (and others)? The authors draw evidence from the communal tombs of the Anfushy necropolis, located on the Pharos Island, which give some clues that the inhabitants – native or immigrant – adapted Egyptian imagery in a particularly local tomb type: Alexandrians, but still in Egypt.

Contact points: The Image and Reception of Egypt and its Gods in Rome starts with promotion of Egypt in the popular imagination of the Romans through the conquest of Egypt by Julius Caesar and Augustus. The authors distinguish between the contrasting ways in which Augustus projected his image: to the Egyptians he appeared in pharaonic dress as autokrator, and to the Romans back home as the victor over a captured people. The authors focus on the imagery of the obelisk as a means by which Augustus and following emperors demonstrated their conquest of Egypt and their ability to ‘out-do’ the Egyptians through the construction of similar monuments of their own.

Traveling Gods: The Cult of Isis in the Roman Empire explores the appeal of the cults of Isis and Serapis to the Romans, particularly with reference to the travels of Vespasian to Alexandria in AD69 and the Severan period (AD193-235) when interest seem to peak. The rich illustrations of images of Isis and Serapis include the famous wall painting of the ceremony outside the temple from Herculaneum (with a detailed description of the events which might be going on there) (p.258), a grave stele of a priestess of Isis (p. 249), the wall painting depicting the arrival of Io in Egypt, from the Temple of Isis in Pompeii (p. 255), a wall painting of priests of Isis found in Stabiae (p. 260) and the unusual Ariccia Relief (p. 269), showing an Isaic ceremony – full of ‘loud music’ and dancing – of which this reader was previously unaware.

Indeed, this book's great attraction is the wealth of beautiful images: the Nilotic scene from Palestrina (pp. 200, 205, 251), Battle Between Pygmies, Crocodiles and Hippopotami from Pompeii (p.253), Head of Serapis from the Mithraeum in London (p. 291) are, as usual, a pleasure. But there are many, smaller, less-well-known images to delight the reader: the coinage of the Ptolemies (p. 188-189) shows a fascinating range of rulers, with a marvellous tetradrachm of Alexander III (as?) Hercules and an octadrachm of Ptolemy II showing Ptolemy I and Berenike I on the obverse and Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II on the reverse – a whole family set of portraits on one coin!

The articles are more than a simple catalogue for the exhibition and open up some worthwhile discussions about the ways in which ancient civilisations intermingled and how they diversified and enriched human experiences. The material could provide some useful reading for an interested student in the sixth form and for teachers as a library resource to dip into. This would be particularly the case for those teaching Alexandria (in Cambridge Latin Course Book 2), the introduction of the worship of Isis in Rome (in Cambridge Latin Course 2 and Roman Religion courses in general), and the image of Augustus in Egypt (in OCR A level examinations on the Imperial Image).