1 Introduction: The Excesses of the Trade-Related Approach

In the presentation of this chapter in draft form, I asked the following question, ‘how do you spot a dodgy international intellectual property claim?’ One possible answer to that question is that those who own intellectual property (IP) rights in one jurisdiction, where those rights have developed from local or regional policies, want those locally grounded rights exported to other legal systems in order to protect IP-related products exported to those jurisdictions. That proposition alone cannot be the only way to spot a ‘dodgy IP claim’ because that is a description of many international IP negotiations where there are attempts to gain at least some international agreement on minimum standards of protection. The ‘dodgy’ aspect arises when incumbents want more protection (without convincing evidence that more protection is needed), and in seeking that greater protection, those incumbents suggest that newcomers will gain immeasurable bounty. This is exactly how the European Union presents its geographical indications (GIs) policy to its trading partners. The argument usually involves three steps. First, multiple GIs have worked in Europe. Second, there are one or two instances of GIs working for developing countries. The following statement from the European Commission illustrates these first two steps:

The protection of geographical indications matters economically and culturally. They can create value for local communities. Over the years European countries have taken the lead in identifying and protecting their geographical indications. They support rural development and promote new job opportunities in production, processing and other related services.

For example: Cognac, Roquefort cheese, Sherry, Parmigiano Reggiano, Teruel and Parma hams, Tuscany olives, Budějovické pivo, and Budapesti téliszalámi.

Geographical indications are becoming a useful intellectual property right for developing countries because of their potential to add value and promote rural socio-economic development. Most countries have a range of local products that correspond to the concept of geographical indications but only a few are already known or protected globally.

For example: Basmati rice or Darjeeling tea through products that are deeply rooted in tradition, culture and geography.Footnote 1

The third step proffered to complete this argument is that because GIs ‘with commercial value are exposed to misuse and counterfeiting’,Footnote 2 GI protection EU style should be the global legal norm in order to prevent this misuse and counterfeiting.

While there is plenty of truth in these statements – after all no one doubts the value of using the origin of a product to sell it when that origin has cachet – there is also a considerable weakness in the logic that purportedly links the three propositions. This weakness is because the success of GIs (as a legal model for exploiting the value in origin of goods) from one territory does not mean that success can be easily replicated in other territories. First, what makes GIs valuable, at least initially, is the place with which the GI-branded product is associated. Such associations (if they are genuine) are not identically replicable. More importantly, the success of GIs is dependent on multiple factors, including investment and infrastructure around the business, industry, place and communities concerned. The legal framework alone, for GIs, is unlikely to create development of the local industry without those other factors being present. Some chapters in this book suggest positive uses of GIs in Asia for those other than Darjeeling tea and Basmati rice,Footnote 3 but a remarkable amount of literature (including the above-quoted statement from the European Union) pinpoints these as examples of how developing countries could succeed in improving their agricultural economy with GIs. This sort of statement is often proffered without an appropriately corresponding analysis of the transferability of the GI mechanism to other communities and other products. In fact, as developing countries repeatedly have shown, the removal of agricultural subsidies in the developed world would make a real difference and enable developing countries to compete in world markets for agricultural products. In a manner prescient of an EU-directed path with GIs, most developed countries have not removed agricultural subsidies (with the notable exception of New Zealand) and, in order for developing countries to compete with developed countries, large developing countries now also subsidise agriculture.Footnote 4 The losers are those countries that cannot afford subsides, particularly the small developing countries, which may agree to implement GI regimes when they are in trade negotiations. This is the kind of outcome that happens when the ‘weak bargain with the strong’.Footnote 5

Just as the GI policy of one country may not be a good fit for another country, evidence that GIs have been effective as a development tool in one community is not evidence that the same model of GIs will be effective in all communities.Footnote 6 As William van Caenegem, Peter Drahos and Jen Cleary have discussed, the success of GIs as a tool in certain parts of the Australian wine industry, for example, is attributable not only to GIs but to certain other factors which are not simply replicable by enacting GI laws.Footnote 7 Their research demonstrates that certain industries have benefited from investment accompanied by GIs in Australia.Footnote 8 This research reveals that a careful calculus is required. The authors suggest that if that benefit of GIs is to be replicated, then Australian autonomy over the design of any law to extend GI protection is crucial.

The international minimum standards for GIs should not be moulded on a legal regime that cannot accommodate appropriate differences between different countries and even different communities in those countries. The benefits of GIs to local communities are only possible with appropriate legal framing to meet and enhance local needs. GIs can be part of a package to enhance development, but a legal mechanism without associated investment cannot effectively function as a source of development. GIs being “part of a package” means exactly that rather than a top-down imposition through trade agreements of a framework and detailed laws designed for the economic conditions of others. Put differently, there is no 100 per cent right or wrong position on GIs even though the debate is polarized. The reality is that one size does not fit all, but several sizes may fit some or possibly even many.

Perhaps the most significant argument against the export of EU-style GI law to developing countries is that while such export has been going on for some time, there are relatively few success stories in developing countries. This would seem to be because a successful sui generis GI regime requires infrastructure and related investment in development, which may be missing. Just as pharmaceutical patents are predominantly a cost to those who do not produce pharmaceuticals, establishing a GI protection regime is largely a cost to those who lack the resources and infrastructure to exploit the origin of goods, in the form of an IP right, in the global economy. In such places, registered GIs will largely be foreign-owned.Footnote 9

The approach of trying to force a one-size-fits-all model is certainly not the exclusive domain of the European Union in its trade agreements.Footnote 10 While the United States does not seek to export GI laws through its trade agreements, it does export its view of how trademark law should dominate and how GIs, if and where they exist, should not trump trademarks, but rather trademarks should prevail over GIs.Footnote 11 Much of the global GI debate is thus characterized by a trans-Atlantic debate and the dominant parties in that debate seek to recruit support for their respective positions in countries around the world through bilateral and mega-regional trade agreements.

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement) GI requirements are minimum standards.Footnote 12 In other words, members of the TRIPS Agreement can implement GI-style protection in a variety of ways. This flexibility around implementation is reinforced by the general provision in the TRIPS Agreement that allows for countries to implement the obligations in their own legal system in a manner they deem appropriate.Footnote 13 It is well documented that since the TRIPS Agreement came into force there has been a proliferation of free trade agreements (FTAs).Footnote 14 These FTAs were initially predominantly bilateral and now frequently involve multiple parties and so are plurilateral, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).Footnote 15 Plurilaterals are often mega-regional agreements. Even though negotiations such as the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are between the European Union and the United States rather than multiple parties, because of the size of the economies of those two parties, such an agreement is mega-regional in terms of the volume of trade it could cover. Geopolitically, the mega-regionals seem to be in competition with each other. The TPP did not include the European Union or China, and the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) plus six parties negotiation for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) does not include the United States, for example.Footnote 16 While at the time of this writing, the TPP will likely not come into force because of the United States withdrawal from it, the TPP IP chapter is emerging in other trade negotiation forums as proposals for negotiation. The text of the TPP relevant to this chapter was introduced into the RCEP negotiations. There is much opposition to such proposals.Footnote 17

Some bilateral FTAs designed and entered into by large economies, particularly the United States or the European Union (known as economic partnerships), articulate one of those major economies’ stance on GIs. Both the United States and the European Union through these FTAs recruit as many countries as possible to one GI stance or another. The trans-Atlantic rivals are dealing with this policy and legal framework collision in the TTIP.Footnote 18 At the political level, the rhetoric captures the difficulty:Footnote 19

Wisconsin Republican Paul Ryan, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, which has jurisdiction over matter of trade policy, condemns European GIs as trade barriers and vows that ‘for generations to come, we’re going to keep making gouda in Wisconsin. And feta, and cheddar and everything else’.Footnote 20

At the same time, the EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström laments that Italian cheeses are being ‘undermined by inferior domestic imitations’ in the United States and vowed to solve the problem through TTIP by ‘getting a strong agreement on geographical indications’.Footnote 21

In Section 2, certain approaches to GI protection in mega-regionals and bilateral FTAs are discussed. Section 3 considers some of the incompatibilities between the EU-dominated and US-dominated approaches. Section 4 raises questions about countries that purport to trade in both regimes, which include Singapore, Korea, Australia and New Zealand. The chapter concludes that unless a compromise is worked out in ongoing trade agreements such as the TTIP and the RCEP (or the proposed Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP)),Footnote 22 the GI debate will worsen, and as it does, the casualties will be small and medium-developing countries and those whose trade agreements have obligated them to both regimes.

2 Mega-Regional Agreements

The European Union is a large region. Its policy on GIs is summarized above.Footnote 23 In contrast, the TTP takes a trademark-centric approach. The TPP was signed on 4 February 2016,Footnote 24 and, as noted above, it is unlikely to come into force. It does, however, provide a detailed example of United States’ GI trade policy and the text is not dead as it is being used in other trade negotiation forums, most notably RCEP. This part refers to the TPP text as it is public, and at the time of this writing the exact state of the RCEP negotiations in relation to the same text is not publicly known. The TPP required that the parties to it protect country names from misuse in a misleading manner.Footnote 25 In addition, the text defined a GI as

an indication that identifies a good as originating in the territory of a Party, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.Footnote 26

This definition is substantively identical to the definition in the TRIPS Agreement and thus immediately flags that the TPP would have gone no further than the TRIPS Agreement in the extent of its protection of GIs.Footnote 27 The TPP did, however, delineate a relationship between GIs and trademarks that the TRIPS Agreement does not. The part of the TPP dealing with GIs sets out what might broadly be described as the United States’ preferred approach. In particular, GIs may be protected through trademarks, a sui generis system or other legal means.Footnote 28 Significantly, there was a requirement that ‘each Party shall also provide that signs that may serve as geographical indications are capable of protection under its trademark system’.Footnote 29 This would have required parties to the TPP with sui generis GI regimes to ensure that the trademark regime provides the same protection. This was a significant gain for the United States, as under the TRIPS Agreement it is quite possible for parties to have a GI system that does not accommodate trademark registrations for protection within the same regime. The various EU GI systemsFootnote 30 are a quintessential example of non-trademark-embracing GI systems. So while the TRIPS Agreement allows for the recognition of GIs in trademark regimes, the TPP required it.

The TPP also included several grounds for opposing the registration of GIs. These grounds included where the GI applied for causes confusion with a trademark which is the subject of an existing registration or even a pending application.Footnote 31 Significantly, GIs could be opposed when the GI is a ‘term customary in common language as the common name for the relevant good’, i.e., the name is generic.Footnote 32 The agreement included guidelines for determining what amounts to customary in the common language, in particular ‘how consumers understand the term’.Footnote 33 Again, this approach was required under the TPP but is a permissible approach under the TRIPS Agreement.Footnote 34 The United States’ potential gain in the TPP had the effect of standing in the way of the EU approach of clawing back generic names, because arguably any list of required names for clawback purposes in future agreements will be inconsistent with the TPP. Some parties to the TPP (and RCEP) have existing GI obligations with the European Union. There is potential for conflicting obligations among the various agreements and so these countries and others will have had to work out (and no doubt will also have to do so as disputes arise) which obligations apply. Australia has already agreed to some EU clawbacks.Footnote 35 Vietnam has agreed to recognize and protect certain EU GIs.Footnote 36 Singapore has agreed with the European Union to review whether the EU GI list should be registered in Singapore.Footnote 37 Further, as one commentator notes, ‘by exporting the principle of co-existence between geographical indications and trade marks the EU is chipping away at regulatory diversity in the area of geographical indications’.Footnote 38 That ‘chipping away’ will likely be harder, if not impossible, in some countries depending on what happens to the mega-regional trade agreements.

In order to have made the TPP compatible with other agreements, it attempted to set other trade agreements in a TPP-aligned framework. There was a general clause relevant to all of the TPP agreement and applicable to FTAs that bind at least two parties that provided that

[i]f a Party considers that a provision of this Agreement is inconsistent with a provision of another agreement to which it and at least one other Party are party, on request, the relevant Parties to the other agreement shall consult with a view to reaching a mutually satisfactory solution.Footnote 39

The above article did not, however, deal with the significant overlaps with agreements made with one TPP party and a non-member of the TPP, such as the European Union. However, as noted above, the TPP parties (and RCEP parties) included several parties who have either existing agreements with the European Union (such as Singapore and Australia) or negotiations with the European Union (such as Canada) that include provisions about GIs. For GIs, there was an explicit regime to deal with the overlap of agreements between TTP parties and non-parties. The result of this was a somewhat complex two-page clause which in essence seeks to make contradictory and opposing approaches to GIs functionally compatible.Footnote 40 The central rule was that

[n]o Party shall be required to apply this Article to geographical indications that have been specifically identified in, and that are protected or recognised pursuant to, an international agreement involving a Party or a non-Party, provided that the agreement:

(a) was concluded, or agreed in principle, prior to the date of conclusion, or agreement in principle, of this Agreement;

(b) was ratified by a Party prior to the date of ratification of this Agreement by that Party; or

(c) entered into force for a Party prior to the date of entry into force of this Agreement for that Party.Footnote 41

The remaining parts of this article explained how information must be provided and how other parts, relating to opposition and administrative procedures, should apply even to prior protected GIs. Under the terms of the TPP, parties must have made available procedures to oppose and review GI registrations. It also required that analogous procedures were applicable to GIs that precede the TPP, even where that GI protection arises under other agreements.Footnote 42 The details of procedures required are somewhat complex.

The irony of this complexity is that the TPP was supposed to make trade easier. The practical results of the relationship between the above-described provisions (and an array of additional side-letters relating to GIsFootnote 43) remain to be tested.

To illustrate some of the complexity, consider an agreement made between South Korea and Australia. Australia was part of the TPP and South Korea is not yet a party.Footnote 44 A side-letter to navigate the differences between Australia’s and the European Union’s approaches to GIs, when South Korea has agreements with both, provides that

[f]inally, I confirm that Korea will allow third parties to oppose any proposal to designate any term as a GI, whether these proposals are made pursuant to the Korea-EU FTA, or to any other future agreements with other trading partners. In addition, before Korea identifies additional terms as GIs under the Korea-EU FTA, it will provide, by published administrative guidelines, that designations of asserted GIs may be opposed in Korea on the grounds that would include: (1) the term is generic in Korea; (2) the term is confusingly similar to a pre-existing trademark or geographical indication that was either previously applied for or registered or established through use; (3) the term is confusingly similar to a well-known trademark; and (4) the term does not meet the definition of a GI.Footnote 45

As mentioned above, another mega-regional trade agreement of particular importance to the Asia Pacific region is RCEP.Footnote 46 The general negotiation principles of RCEP state that

[t]he text on intellectual property in the RCEP will aim to reduce IP-related barriers to trade and investment by promoting economic integration and cooperation in the utilization, protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights.Footnote 47

A purported working draft of the negotiations dated October 2014Footnote 48 proposes protection of trademarks that pre-date GIsFootnote 49 and more broadly provides that

[e]ach Party recognises that geographical indications may be protected through various means, including through a trademark system, provided that all requirements under the TRIPS Agreement are fulfilled.Footnote 50

As noted above, South Korea and Japan are reputed to have introduced equivalent proposals to those that are found in the TPP IP chapter as a possible model for negotiation in RCEP.Footnote 51

It is important to include in this group of trade agreements that have been negotiated after the TRIPS Agreement, the mega-economy bilaterals, particularly as these are significant in the GI debate. As noted above, the negotiations between the European Union and the United States in the TTIP are significant. If those trading blocs can reach a workable compromise, then much of the rest of the world may also be able to do so.

The Canada-EU Trade Agreement (CETA) negotiation shows a kind of complicated compromise.Footnote 52 In CETA, GIs are defined as

an indication which identifies an agricultural product or foodstuff as originating in the territory of a Party, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the product is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.Footnote 53

Notably, this definition explicitly excludes the application of GI rules to non-agricultural and foodstuff products, which the European Union extends some GIs to and proposes to extend GIs even further.Footnote 54

The CETA text provides a general requirement for the protection of GIs that are listed in annexes to the agreement.Footnote 55 The protection must still be provided even where the true origin of the product is indicated or when the GI is used in translation or accompanied by expressions such as kind, type, style and the like.Footnote 56 The parties must also ‘determine the practical conditions under which the homonymous indications … will be differentiated from each other’.Footnote 57

There are some detailed exceptions, including that Canada shall not be required to provide laws to prevent the use of some terms including asiago, feta, fontina, gorgonzola and Munster, when such terms are accompanied by expressions such as kind, type, style and imitation.Footnote 58 The combination of names and terms, e.g. ‘feta style’, must be both legible and visible.Footnote 59

Overall CETA is a well-developed – even if complex – compromise between the extremities of the GI debate. At one extreme of the debate is insistence on the necessity of a sui generis GI system and at the other extreme the view that only trademarks are appropriate and necessary. There is some considerable detail required to reach CETA’s compromise and these details accentuate some of the incompatibility of the approaches found in the other mega-regionals.

3 Policy Incompatibilities of Approaches to Geographical Indications in Trade Agreements

This section does not discuss the various technical differences between GI and trademark systems, but rather focuses on some of the policy incompatibilities that have arisen and arguably are becoming entrenched in the mega-regional framework. As a starting point, the extension of local success to the global arena raises questions about the normative basis for so doing and the consistency between local policy and globalization of that policy.

The origins and justifications for GIs, which are linked to local conditions such as the terroir,Footnote 60 risk distortion when linked to other parts of the world through the global trading. The overall basis for the claim for greater global harmonization of GIs is to protect the products that are ‘genuinely’ GI-labelled, not just in the domestic market, but also in foreign markets. As noted above, it is in export markets (both existing and potential) that the European Union claims its GI products are unfairly imitated. Notably, however, there can be no claim over making equivalent products,Footnote 61 and the complaint is about applying the GI to them. While there are some notoriously bad products which draw on GI products and their names, there are plenty of high-quality products which compete with GI products, both nationally and internationally, but that have not used GIs to acquire a market share.Footnote 62 The GI approach assumes that such products may be better off with GIs, but that is not necessarily so.Footnote 63 Moreover, until appropriate analysis of local conditions, including investment and infrastructure, is in place, such claims are mere assertions calculated to push the GI export agenda rather than to encourage quality local-made food.

A localized reputation (even if extensive) is not, however, the same as a globalized reputation and so the need for export protection for many GI products is not necessarily obvious to the importing markets. The ubiquitous example of champagne is exactly on point. The value of the GI is intimately connected to the geographical region as both product and production factors are dependent on features of the Champagne region.Footnote 64 International protection, outside of the European Union, of champagne (and other GI products) occurs under various regimes. These include sui generis recognition of GIs on similar grounds to the European Union, clawback provisions in trade agreements that have made ‘ungeneric’ the genericFootnote 65 and claims to distinctive reputation in the local market that can give rise to either a certification or collective trademark and in some jurisdictions grounds for action under a common-law doctrine such as passing off.Footnote 66 The latter two approaches can include geographical and place-based arguments as relevant to reputation and consumer perceptions; however, neither trademarks nor passing off necessarily depends on any direct connection to place for any protection.Footnote 67

One might even argue that calibrations of local law, which are framed and developed to meet local needs (that is exactly what GIs represent), are the antithesis of the case for globalization. The framework of IP that utilizes minimum standards and domestic discretion, including modes of implementation, within the minimum standards framework creates the mechanism through which the global is reflected in the local and vice versa. The question, in relation to GIs (and all IP), is how prescriptive should the minimum standards be and thus how much autonomy is left to local discretion and how much is governed by international rules. The greater the level of prescription at the international level, the less room for national discretion and the more likely that the international obligation will be based on models designed for the conditions of some, but not all, economies. This is the top-down approach (edging towards a one-size-fits-all approach), which the trade agreements, discussed in Section 1 of this chapter, exemplify. The TRIPS Agreement, on the other hand, leaves much GI detail to national autonomy. However, neither the European Union nor the United States are prepared to stop at the TRIPS Agreement minimum standards level of protection, but rather seek to globalize their own agendas.

The fundamental objection to too much global harmonization or inflexible rules is the risk that GIs, rather than protecting genuine culturally anchored outputs, function as barriers to trade. As the development of globalized IP rules has shown, particularly in other areas such as patents, globalized rights tend to favour incumbents over new entrants. So how much protection is enough protection? Put differently, what protection of GIs globally is a legitimate use of IP as a non-tariff trade barrier and what level of GI protection exceeds that level?Footnote 68

Internationally, IP is protected in different jurisdictions on the basis that the promise of exclusivity can provide an incentive for innovation and creativity. There is much commentary about the effectiveness and ineffectiveness of incentives and in which arenas they work and when they do not.Footnote 69 The argument that GIs can assist with rural development that is consistent with cultural and sustainable practices is a kind of incentive argument. The counterargument is that GIs can sometimes be used to disincentivize innovation because they require production processes to conform to rules that do not allow for innovative alterations.Footnote 70 Neither representation of GIs is true all of the time, but both are true sometimes.

In most areas of IP, both incentivizing and disincentivizing goes on. Balancing these tensions is core to how the IP regime (and some quasi-property IP rules) functions. It is known that exclusivity restricts third-party users and, thus, IP rights block immediate follow-on innovation, but temporal restrictions justify the imposition of exclusive rights.Footnote 71 Trademarks and GIs are different because they do not have temporal restrictions (unless fees are not paid) and so their overreach can cause disincentivizing effects with no possibility of change. In trademark law, this takes the form of trademarks substituting for copyright (and in some jurisdictions, design) after expiry of the copyright.Footnote 72 With GIs, the danger is that the GI protects too much both in the jurisdiction of origin and in export markets. As far as export markets are concerned, the issue is whether GI protection in the export market really incentivizes local development that is consistent with cultural and sustainable practices. In the jurisdiction of origin, consider, for example, the quintessential example of a GI protecting a product created through local practice. If that protection is extended to protect the method of production, then, in fact, the GI is protecting know-how (as opposed to innovation). This know-how is an area that copyright and patent protection, in particular, are supposed to not cover.Footnote 73 Copyright protects original works. Patents are granted for processes and products, provided they are inventions that are new, involve inventive step and are useful.Footnote 74 There is a fine line between protecting these things and protecting know-how. The cumulative effect of both protecting the know-how of process and production methods through GIs, by extending the GI justification relating to the commodification of products, and requiring protection of GIs when they are used beyond their locality in export markets, means that GI protection is all encompassing. At that point, what is left? Where is the space for innovation in and around existing IP? Unless GIs are appropriately framed, they will become the latest mechanism for IP overreach.

The preference for property or property-style rules to govern IP is based on the proposition that property comes after (ex post) creation or innovation and so the potential grant of property rights incentivizes creativity and innovation. Put differently, IP rights are a goal to reach and a reward when that goal is reached.Footnote 75 Subsidies are thought to do the opposite because they are ex ante to creativity and innovation. This is why the World Trade Organization (WTO) system allows subsidies to be challenged where they amount to trade barriers. The details of impermissible subsidies, for WTO members, are found in the WTO Subsidies and Counterveiling Measures Agreement (SCM).Footnote 76 In that framework, the issues of particular interest to the relationship between IP and subsidies, is the rules around research subsidies. In the early stages of the SCM the rules allowed subsidies for research and development without questioning them (these were known as green light subsidies). The SCM contained a provision that later moved these ‘green light’ subsidies to amber status. This made such subsidies actionable, rather than permissible simply because they were connected to research.Footnote 77 In other words, research subsidies could be challenged under the SCM rules.

When IP rights overprotect, they take on the economic characteristics of subsidies.Footnote 78 Too many incentives can lead to a lack of innovation. When it is ‘raining carrots’,Footnote 79 one hardly needs to pursue costly innovation if substantive reward can be obtained from the existing regime. Expanded GI protections in foreign markets for products that do not necessarily retain their initial reputation in those foreign markets are, therefore, arguably overprotected. If the rationale for GIs is protection of the local to generate rural development, then that rationale does not simply slip over into export markets. In the export market, the desirability of protecting the local may simply disappear if the local product cannot compete with exports. The local product may, however, be cheaper and as the GI product is a speciality good it is often higher priced. That price may be justified on the assumption, which is perpetrated by both producers and consumers, of better quality. Global GI rules do not require proof of quality and they should probably not be formulated to do so because the necessary administration and resources to retain such a system are very costly and totally impractical for many countries.

Irene Calboli argues that the connection between the GI and the terroir should be strictly enforced so as to maintain the proper scope of GI protection.Footnote 80 In many ways, this argument is attractive because it is an attempt to decouple overprotection, for what she calls ‘market-strategies’, from deeply held place-based cultural claims. Further, there are numerous examples where local culture cannot sustain global markets and attempts to do so undermine local traditions and can create sustainability and development issues. These sorts of issues will vary from place to place, just as the effectiveness of GIs varies.

If Calboli’s argument is correct, then it is also an important reason why GIs are not often a good fit for traditional knowledge, especially where the claimants of traditional knowledge have been dispossessed of their land at one time or another or permanently, which is often the case with indigenous peoples.

I have argued elsewhere that the GI framework is not a good framework for protecting many aspects of traditional knowledge.Footnote 81 The argument is multifaceted, but in essence rejects the similarities between GIs and claims to traditional knowledge (collective nature of ownership and possibility of indefinite protection) as for the most part superficial similarities. GIs enable the commodification of tradition, and claims for protection of traditional knowledge are often not about commodification.Footnote 82 In addition, the resources that are needed for the development of communities seeking traditional knowledge protection will not be achieved through having to pay for the costs of a GI framework and registration without investment in real development and infrastructure.Footnote 83

That said, there is a similarity between what might be an appropriate GI framework of minimum standards and the appropriate framework for protecting traditional knowledge. If both frameworks are aligned with their normative underpinnings, which ought to be primarily about local communities, then any global minimum standards of protection should enable some considerable flexibility in implementation. This flexibility allows for appropriately calibrated domestic application based on local needs and rural development. Such drivers of GI policy are unlikely to be realized by detailed harmonized norms, but through a framework of minimum standards. The same case for a pluralistic approach to traditional knowledge can be made. To be clear, however, the appropriate framework for traditional knowledge is not the GI commoditization framework, but the similarity may be that pluralistic approaches need to be incorporated into the respective legal frameworks if the systems remain true to their normative drivers.Footnote 84

It is important to remember that GIs, as intangible IP rights, are separate legal entities from the goods to which they attach. Using IP analogies, extensive GI protection has a parallel to some aspects of well-known trademarks. Well-known trademarks receive significant worldwide protection.Footnote 85 Small- and medium-sized businesses cannot hope for this level of protection globally and often this means the businesses of small and medium countries cannot rival large economies on the international stage. Well-known GIs are not those of small- and medium-sized businesses either.

If the normative underpinning of GIs is the drive for local culture and sustainability, then that alone does not obviously require global rules. In fact, such aims may be more achievable without global rules. To the extent that minimum standards in GIs around the globe can be sufficiently broad to allow for local differences, such as the CETA compromise discussed above, the regime may work. The normative basis for harmonized rules is, however, somewhat hazy outside of the need to strike a trade deal. It may, therefore, be that not only are the multifaceted approaches to GIs well and truly here to stay; they may have to learn to function better together and support both legal and cultural diversity.

4 Trading in Both the EU and the US Geographical Indications Regimes

As noted in Section 1 of this chapter, there are several countries with trade agreements, with both the European Union and the United States, that purport to operate (one might say with prodigious care) under both trade regimes and other countries that are poised to do so. Carefully calibrated local laws might be able to meet the demands of both frameworks, but as noted above, such approaches are complex, expensive and require legal ingenuity and perhaps even fictions on some occasions.

Trade agreements are not only about GIs (or IP rights); they are also about goods and often include considerable negotiation, even if not resolution, about dairy products and the reduction of subsidies and market access. The European Union uses GIs to protect dairy products whereas the United States, Australia and New Zealand for the most part do not. That is not to suggest that other IP rights such as trademarks do not play an extensive role in the dairy sector. They most certainly do, and dairy products are one of the most contentious sectors in the international GI debate.

To illustrate further the problem of complex overlaps and potential incompatibilities of GI provisions in trade agreements, consider the following. New Zealand exports not only dairy products but also commodities used in dairy products such as milk. Imagine a product made in Australia and called ‘parmesan’ (and trademarked with other names) that includes New Zealand milk products. That product is made by an Australian company with New Zealand owners and is marketed under a label that alludes to Italian culture. It does not use the protected GI (or certification trademark in Australia and New Zealand) ‘Parmigiano-Reggiano’. Instead, the packaging utilizes techniques to suggest ‘Italian style’, such as green and red colouring. Under Australia’s and/or New Zealand’s trade agreements with Singapore (and other countries) that product has market access to Singapore. Under some trade agreement rules, such a product uses what is described as a common name (which is not recognized as a GI) and the mere use of colour does not give rise to protectable rights. It is arguable that this use of ‘geography’ could raise a GI issue in countries that have GI regimes. For the avoidance of doubt, it is not clear that Singapore’s GI regime will allow such concerns to be raised in a dispute, but it may. Another point of the example is to show that when Singapore (and other countries in analogous positions) agreed to create a sui generis GI regime with the European Union, it already had trade and market access obligations in relation to goods that it had to take into account and will have to continue to take into account when implementing and enforcing its GI regime.

In relation to GIs alone, the need to take into account existing trade agreements is evident in the text of the US-Singapore and EU-Singapore trade agreements.Footnote 86 The agreement with the United States embodies a first-in-time-first-in-right principle.Footnote 87 The later EU-Singapore agreement provides, therefore, that a GI that conflicts with a prior existing trademark in Singapore is capable of being registered only with the existing consent of the trademark holder.Footnote 88 Whatever can be said about the ingenuity of Singaporeans to try to navigate the conflicting interests of its trading partners, such a complex regime requires extensive legal knowledge and resources, which will not be a solution available to many countries, and particularly developing countries.

This sort of balancing of interests is precisely why the CETA rules look as detailed as they do, but it is not at all clear that Singapore’s rules or indeed those in CETA and potential regimes, like the text of the TPP, are compatible. At a high level, they may appear to be so, but that remains to be tested. It is difficult to see how countries that have signed up to several regimes can easily make their obligations compatible.

5 Conclusion

On a case-by-case basis, incompatibilities in GI frameworks may be ironed out if and when disputes are resolved. The tug of war between the European Union and the United States to control the international GI framework is, however, costing other trading nations too much in the negotiation and implementation process. The complex hybridized systems are imposed via top-down models rather than generated locally on a fit-for-purpose basis.

Incumbents of the GI system seek international harmonization rather than any flexible minimum standards that would allow various cultures to calibrate and adjust their laws according to local needs. At the same time, the major opponent of the GI system, the United States, seeks its version of trade-mark requirements as a way to ‘correct’ EU policy. Neither approach is satisfactory. In both scenarios, the only likely winners are those whose products are well known.

1 Introduction

Under European Union (EU) law, geographical indications (GIs) are protected under three guises: the protected GIs (PGI), the protected designations of origin (PDOs), and the traditional specialities guaranteed (TSGs). For the EU, the protection of its GIs in and outside of Europe is a very relevant economic issue, as the value of GI products in 2010 was estimated at €54.3 billion, of which the sale of wines accounts for more than half.Footnote 1 It is no surprise that the EU is vigorously trying to obtain protection for its GIs in major trade partner nations. However, in the context of the World Trade Organization (WTO), New World nations, most notably the North Americas, Australia and New Zealand, have consistently rejected the notion of a multilateral register for GIs that is dominated by European claims. Thus, it comes as no surprise then that in the context of the WTO negotiation mandate contained in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)Footnote 2 under Article 23,Footnote 3 no significant progress has been made or can be expected in the near future.

As a result of this stalemate at the multilateral level, the strategy of the EU has been to place the protection of GIs at the heart of its intellectual property (IP) chapters in bilateral trade and investment agreements (BTIAs). In particular, Article 3(1)(e) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)Footnote 4 provides the EU with the exclusive competence to deal with common commercial policy.Footnote 5 According to Article 207(1) of the TFEU,Footnote 6 this includes commercial aspects of IP. Not surprisingly, the number of EU BTIAs is quickly growing and the EU-South KoreaFootnote 7 and EU-SingaporeFootnote 8 Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), the recent Canada-EU Trade Agreement (CETA)Footnote 9 and the EU-Vietnam Trade AgreementFootnote 10 all contain annexes listing the GIs that are to be protected in the partner countries as part of the trade deal.

The nature of BTIAs, however, is that these are mixed agreements dealing with issues of tariffs and trade, but also with investment protection and, increasingly, investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS). In the context of the ongoing negotiations ISDS has become a highly controversial issue, including in the negotiation surrounding the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership Agreement (TTIP).Footnote 11 The controversy lies in the fact that the policy freedom of a signatory state to an agreement containing ISDS may become limited on account of investor expectations that have to be honoured. The controversy is remarkable to the extent that ISDS has been a prominent feature in international trade and investment frameworks since the mid-1970s. In fact, the proliferation of ISDS in bilateral agreements is so widespread and affects so many trading nations globallyFootnote 12 that it is almost surprising that relatively few cases have been brought so far claiming violations under these provisions. Also regional trade agreements like the North American FTA (NAFTA)Footnote 13 and the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP)Footnote 14 contain ISDS clauses.

However, the concept of ISDS is relatively new in the field of IP. This is due to the fact that IP only became a global trade issue relatively recently through the integration of IP standards and IP enforcement in the WTO framework. That said, IP is also peculiar in the sense that the valuation of IP as an object of property that can be viewed as an investment is also a relatively new concept. Even now, various approaches to valuation according to income-based, market-based and review of cost-based approaches, coupled with diverging reporting standards, yield different results.Footnote 15 Still, the number of ISDS complaints is rising and the first cases involving core issues of IP expropriation are currently pending.

Of all IP rights, the EU regime on the protection of GIs invites a substantial involvement of public authority in defining GI specifications, as well as the quality maintenance thereof. This means that any change in the specification may give rise to an investor–state dispute. This chapter charts the likelihood that GIs may become a bone of contention under constitutional expropriation protection laws, WTO disputes and ISDS, and concludes that given the nature of GI protection’s inclusion of specifications, there is a higher state involvement, and accordingly, a higher likelihood that measures negatively affecting a GI proprietor’s rights can be attributed to a state.

2 Geographical Indications and Specifications in the European Union

The EU PGI, PDO and TSG schemes operate on the basis of registration in the Database of Origin and Registration (DOOR).Footnote 16 There are also product-specific regimes and databases, such as the E-BACCHUSFootnote 17 for wines and E-SPIRIT DRINKSFootnote 18 for spirits. EU law also protects GIs for aromatized wine products.Footnote 19 Generally, EU law applies to products originating from EU Member States and third countries that comply with EU rules. Alongside the existing public registries, there are several certification schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs in the EU. These range from compliance obligations with compulsory production standards to additional voluntary requirements relating to environmental protection, animal welfare, organoleptic qualities, etc. Also, all kinds of ‘fair trade’ or ‘slave free’ epithets fall within these voluntary regimes. All these regimes should, however, be in compliance with the ‘EU best practice guidelines for voluntary certification schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs’,Footnote 20 in order to be in compliance with EU law.

In 2005, the United States (the US) and Australia successfully challenged the legitimacy of EC Regulation 2081/92Footnote 21 on GIs for agricultural products and foodstuffs, which was the regulation in force at the time, before the WTO. The regulation contained a number of contentious provisions, namely on (1) the equivalence and reciprocity conditions in respect of GI protection; (2) procedures requiring non-EU nationals, or persons resident or established in non-EU countries, to file an application or objection in the European Communities through their own government, but not directly with EU Member States; and (3) a requirement on third-country governments to provide a declaration that structures were in place on their territory enabling the inspection of compliance with the specifications of the GI registration. On all three points, the WTO PanelFootnote 22 found violations of Article 3(1) of TRIPSFootnote 23 and Article III(4) of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994 (GATT),Footnote 24 and that the GATT violations were not justified by Article XX(d) of GATT.Footnote 25 In the Australian Report, the WTO Panel further found that these inspection structures did not constitute a ‘technical regulation’ within the meaning of the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT).Footnote 26 As a result, the EU changed its regime in March 2006 to ensure compliance with the WTO regime, currently primarily through the Foodstuffs Regulation,Footnote 27 and corresponding provisions in the other Regulations.Footnote 28 The scope or protection extends to consumer deception;Footnote 29 commercial use in comparable products;Footnote 30 commercial use exploiting reputation;Footnote 31 and misuse, imitation or evocationFootnote 32 in relation to the registered GI. The enforcement of a GI is, however, a private law issue.

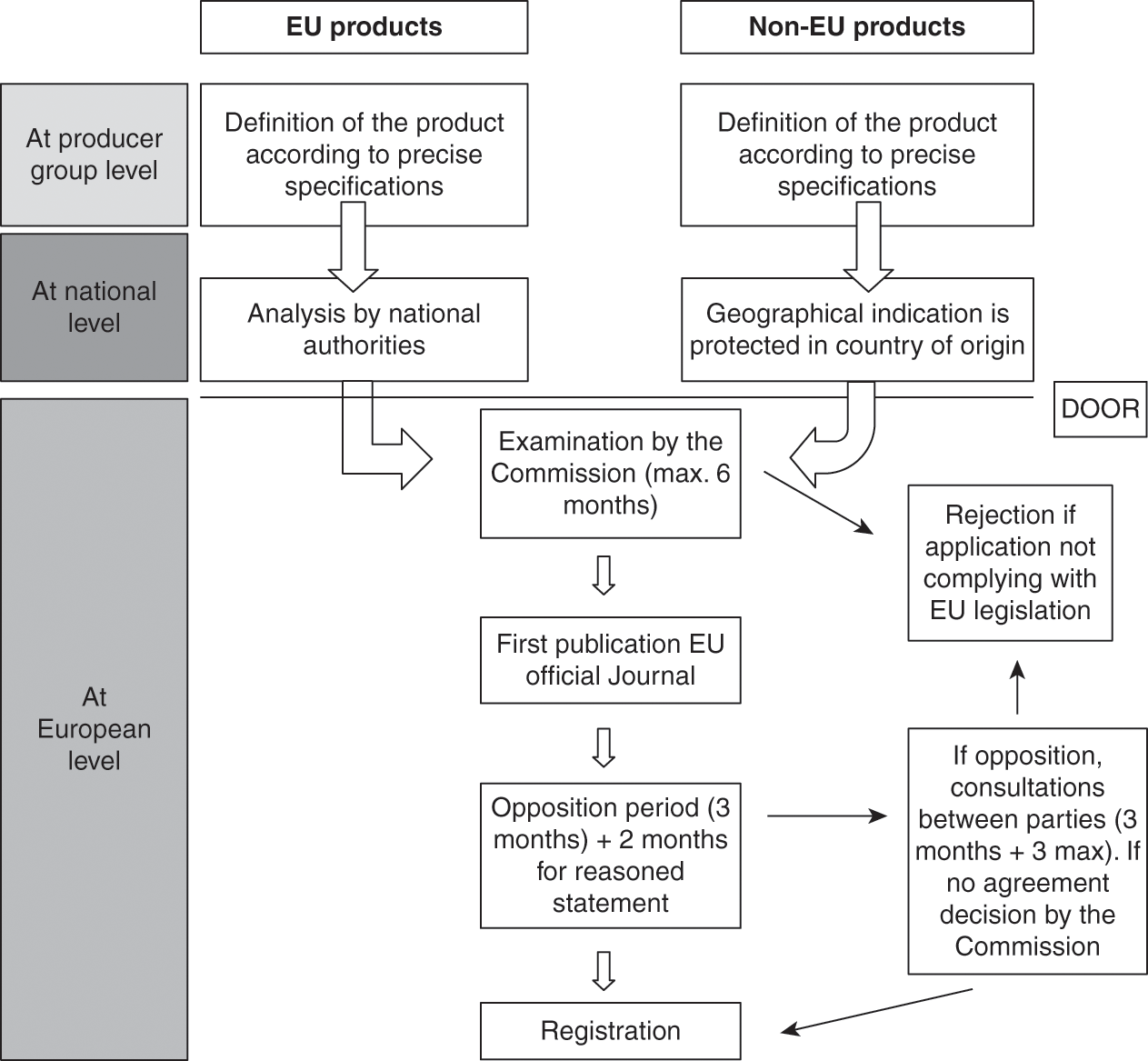

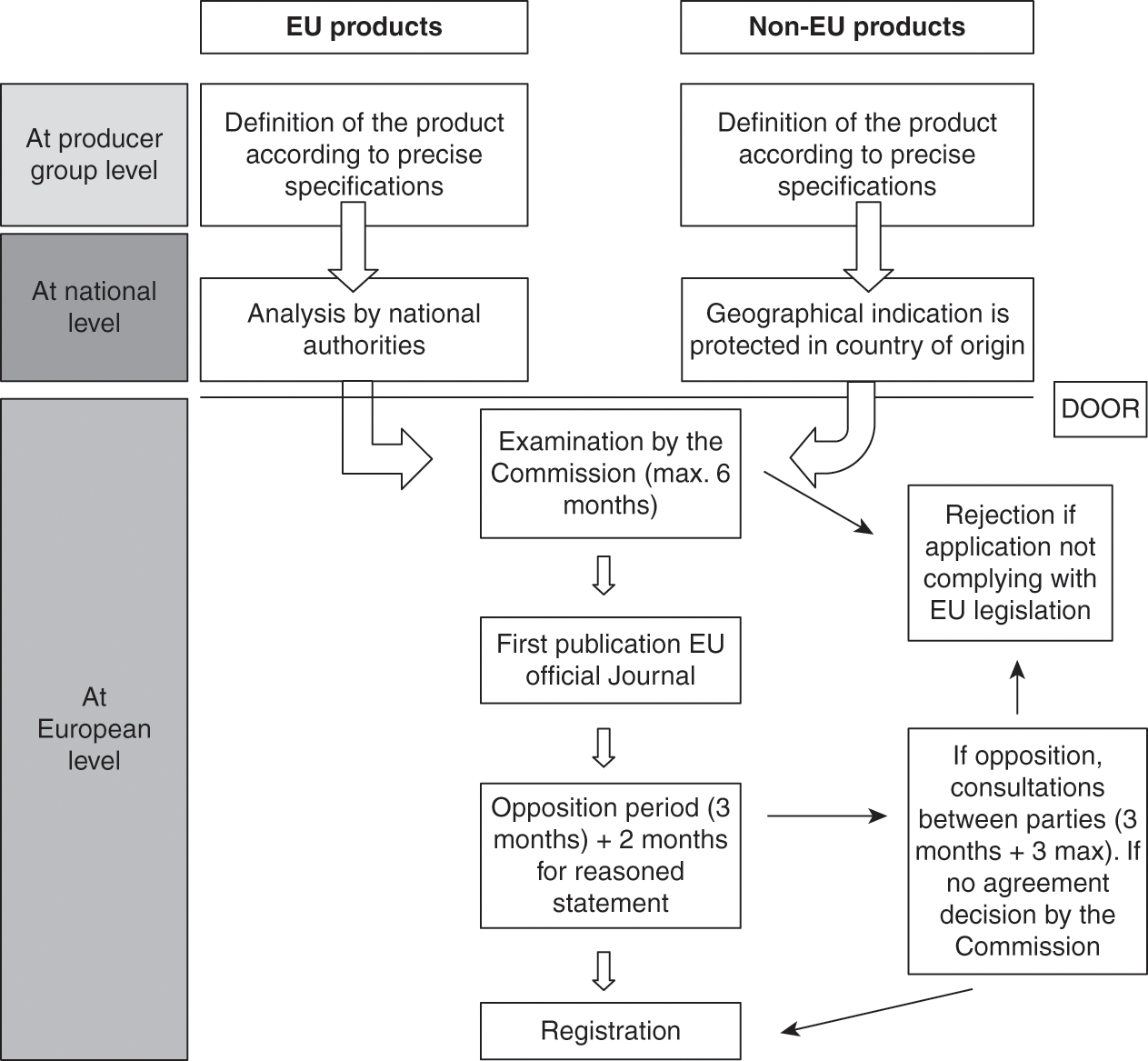

More interesting, for the purpose of this chapter, however, is the product specification – its establishment, inspection and enforcement – as this requires the involvement of public authority. The definition of the product according to precise specifications and its analysis by national authorities is a process integral to the registration of the GI at the EU level.

The definition of the product comprises the following elements: the product name, applicant details, product class, the name of the product, the description of the product, a definition of the geographical area, proof of the product’s origin, a description of the method of production, the linkage between the product and the area, the nomination of an inspection body and labelling information.Footnote 33 For PDOs, all production steps must take place within the geographical area, whereas for PGIs at least one production step must take place within the geographical area. It is also at this point where specific rules concerning slicing, grating, packaging and the like of the product to which the registered name refers may be stated and justified. Given the fact that these types of conditions on repackaging or slicing result in geographical restrictions having strong protectionist and anticompetitive effects, they are among the most controversial specifications.

In 1997, the Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma,Footnote 34 the Italian trade association of 200 traditional producers of Parma Ham, sought injunctions against Asda Stores in the United Kingdom to restrain them from selling pre-sliced packets of prosciutto as ‘Parma Ham’, a protected PDO. The ham was sliced by a supplier of Asda outside the production region, and pre-packaged without supervision by the inspection body responsible for enforcing EU production regulations. The slicing of the ham itself cannot be problematic as such,Footnote 35 but the question is whether slicing the ham away from the consumer’s eyes and offering them as a pre-packaged product not bearing the Consorzio’s mark would be infringing upon the PDO. The Consorzio’s argument was that the consumer could not verify the origin, and the quality of the ham could not be guaranteed. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEUFootnote 36) heldFootnote 37 that protection conferred by a PDO did not normally extend to operations such as grating, slicing and packaging the product. The CJEU, however, stated that those operations were prohibited to third parties outside the region of production only if they were expressly laid down in the specification, and if this condition was brought to the attention of economic operators by adequate publicity in Community legislation. The latter was not yet the case under the old regime.Footnote 38 Under Article 8.2Footnote 39 of Regulation 1151/2012, the product specification is now to be included in the single document that is contained in the DOOR register, and the Consorzio can now enforce its slicing and packaging rules.

The specification also contains the names of the inspection bodies responsible for enforcing EU production regulations.Footnote 40 In each Member State, public authorities or government agencies are entrusted with this task. When it comes to defining or redefining the specification, however, quite a lot of state involvement can be observed. A case on point is the enlargement in 2009, actively supported by the Italian government, of the area of production for ‘Italian Prosecco’.Footnote 41 The production of this sparkling wine has been traditionally confined to the Veneto Region around Venice, but it was suddenly ‘strategically’ expanded to include the town of Prosecco, which is located in the Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region near Trieste and the Slovenian border. This is the place where the Prosecco grape variety is believed to have originated from. Yet, upon accession to the EU in 2013, Croatia found that its sweet Prošek dessert wine, which is different from Italian Prosecco in all aspects of methods of production and grapes used, could no longer coexist in the EU with Italian Prosecco.Footnote 42

In short, GIs are peculiar in the sense that they constitute a type of IP right where a lot of state involvement can be observed, especially in the drafting, maintenance and alteration of the GI’s specification. This may lead to the consortium of GI producers, or the (semi-)state authority itself to alter a GI specification after the GI has been registered. As a consequence, this may give rise to investor–state disputes by private parties that may consider themselves affected by these changes or the recognition of GIs in general (in that they may no longer be able to market their products under the same or similar names), since many of these measures leading to the definition of the GI’s specification can be directly or indirectly attributed to the state.

3 Geographical Indications as Property

Like other IP rights, GIs are protected as proprietary interests. This becomes apparent from the WTO Panel report in EC – Trademarks and Geographical Indications,Footnote 43 but even more so in the context of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

In the case of Anheuser-Busch v. Portugal, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) held that the protection provided for by Article 1 of the Protocol No.1 to the ECHR,Footnote 44 which guarantees the right to property,Footnote 45 is applicable to IP as such.Footnote 46 This means that the owner of an intellectual ‘possession’ is protected in respect of (1) the peaceful enjoyment of property; (2) deprivation of possessions and the conditions thereto; and (3) the control of the use of property by the state in accordance with general interest. Inherent in the convention is the recognition that a fair balance needs to be struck between the demands of the general interests of society and the requirements of the protection of the individual’s fundamental rights.Footnote 47

Since 2000 the EU Charter on the Protection of Fundamental Human RightsFootnote 48 recognized similar principles that EU citizens can rely on. In Scarlet Extended v. Sabam,Footnote 49 the CJEU held:

The protection of the right to intellectual property is indeed enshrined in Article 17(2) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (‘the Charter’). There is, however, nothing whatsoever in the wording of that provision or in the Court’s case-law to suggest that that right is inviolable and must for that reason be absolutely protected … The protection of the fundamental right to property, which includes the rights linked to intellectual property, must be balanced against the protection of other fundamental rights.

Opinions on how this balance should be struck, however, naturally differ, depending on one’s perspective. In a European case, British American Tobacco,Footnote 50 involving challenges to restrictions on advertising, branding and trademark communication in relation to tobacco products, the CJEU held that restrictions on trademark use requiring labels to display health warnings by taking up 30 per cent of the front and 40 per cent of the back of a cigarette packageFootnote 51 amount to a legitimate restriction that still allows for a normal use of the trademark. The tobacco companies had argued that there is a de facto expropriation of their property in the trademark. A similar argument was made in the well-publicized constitutional challenge case to the Australian Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011.Footnote 52 The High Court of Australia in BAT v. Commonwealth of AustraliaFootnote 53 held that there was no acquisition of property that would have required so-called ‘just terms’ protection under the Australian constitution. Yet it is the Australian Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 that has also produced two WTO challenges to tobacco plain packaging, by UkraineFootnote 54 and by a number of other states.Footnote 55 Although Ukraine suspended its proceedings on 28 May 2015, the litigation by Honduras, Cuba, Indonesia and the Dominican Republic remains unaffected. Plain packaging also sparked investor–state disputes.Footnote 56 These cases raise questions on the remaining policy freedom that nation states have in regulating the use or exercise of IP in light of societal interests, such as public health, in the context of multilateral and bilateral trade agreements, and investment protection agreements.

4 Investor–State Dispute Settlement and WTO Law

Bilateral free trade and investment agreements may provide additional protection to investors in relation to their investments that are then considered to be ‘possessions’ in the state where such investments have been made. The question is then to what extent protection granted by means of bilateral agreements changes the legal relations between WTO Members. Although the annexes to EU BTIAs list GIs that are to be protected under the agreement,Footnote 57 it remains to be examined what their effect under the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) is.

The WTO Appellate Body, in Mexico – Taxes on Soft Drinks,Footnote 58 rejected the notion that parties can modify WTO obligations by means of an FTA, whereas the WTO Panel in Peru – Additional DutyFootnote 59 was not so categorically opposed. In the latter case, there are numerous references to Peru’s freedom to maintain a price range system (PRS) under an FTA with complainant Guatemala. The WTO Panel, however, observed that the FTA in question was not yet in force, and that its provisions should therefore have limited legal effects on the dispute at hand. Peru’s arguments in respect of the FTA were that, even assuming that Peru’s PRS was WTO-inconsistent, Peru and Guatemala had modified between themselves the relevant WTO provisions to the extent that the FTA allowed Peru to maintain the PRS. Upon appeal, the Appellate Body stated:

[W]e are of the view that the consideration of provisions of an FTA for the purpose of determining whether a Member has complied with its WTO obligations involves legal characterizations that fall within the scope of appellate review under Article 17.6 of the DSU.Footnote 60

However, it also considered that WTO Members cannot modify WTO provisions such that these become WTO-inconsistent, even if these changes ‘merely’ operate bilaterally inter partes and not amongst all WTO Members. In particular, the Appellate Body held:

We note, however, that Peru has not yet ratified the FTA. In this respect, it is not clear whether Peru can be considered as a ‘party’ to the FTA. Moreover, we express reservations as to whether the provisions of the FTA (in particular paragraph 9 of Annex 2.3), which could arguably be construed as to allow Peru to maintain the PRS in its bilateral relations with Guatemala, can be used under Article 31(3) of the Vienna Convention in establishing the common intention of WTO Members underlying the provisions of Article 4.2 of the Agreement on Agriculture and Article II:1(b) of the GATT 1994. In our view, such an approach would suggest that WTO provisions can be interpreted differently, depending on the Members to which they apply and on their rights and obligations under an FTA to which they are parties.Footnote 61

In the case at hand, this means that Peru under the FTA is only allowed to maintain a WTO-consistent PRS, which should meet the requirements of Article XXIVFootnote 62 of the GATT 1994, which permits certain specific deviations from WTO rules. All such departures require that the level of duties and other regulations of commerce applicable in each of the FTA members to the trade of non-FTA members shall not be higher or more restrictive than those applicable prior to the formation of the FTA.Footnote 63

In Turkey – Textiles,Footnote 64 the Appellate Body held that the justification for measures that are inconsistent with certain GATT 1994 provisions requires the party claiming the benefit of the defence provided for by Article XXIV GATT 1994 lies in closer integration between the economies of the countries party to such an agreement. It is clear that Peru’s PRS measure cannot be interpreted as a measure fostering closer integration; rather, it results in the opposite. The GI ‘claw-back’ annexes to EU BTIAs can arguably be held to contain obligations that approximate the economies of the parties to the agreement, providing the holder of such a GI legal certainty not only as to the protection and enforcement of the GI but also as to the protection of an ‘investment’ in terms of production and marketing of a GI product.

The WTO Dispute Settlement Body has meanwhile established dispute settlement panels in relation to Australia’s tobacco plain packaging measure. GIs are part of the property package on which the claim is based. The five complainants are arguing that the measure is inconsistent with Australia’s WTO obligations under TRIPS,Footnote 65 TBTFootnote 66 and the GATT 1994.Footnote 67 In respect of trademarks and GIs, the claim is that restrictions on their use amount to an expropriation of property. There is only one caveat that will be of relevance to a decision in these casesFootnote 68 in the context of TRIPS, and that is that in EC – Geographical Indications, the panel held:

[T]he TRIPS Agreement does not generally provide for the grant of positive rights to exploit or use certain subject matter, but rather provides for the grant of negative rights to prevent certain acts. This fundamental feature of intellectual property protection inherently grants Members freedom to pursue legitimate public policy objectives since many measures to attain those public policy objectives lie outside the scope of intellectual property rights and do not require an exception under the TRIPS Agreement.Footnote 69

5 Investor–State Dispute Settlement and Geographical Indications

The ISDS case of Philip Morris Asia v. AustraliaFootnote 70 shows that investor–state disputes can be brought in support of, or as an alternative to, constitutional and WTO challenges. In this case, Philip Morris Asia challenged the tobacco plain packaging legislation under the 1993 Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of Hong Kong for the Promotion and Protection of Investments. The arbitration was conducted under the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Arbitration Rules 2010.Footnote 71 In a decision of 18 December 2015, the Tribunal hearing the case ruled that it had no jurisdiction to hear Philip Morris Asia’s claim.

However, it is important to realize that the proliferation of ISDS clauses in bilateral trade agreements is increasing. Investor–state dispute settlement revolves around the question of whether expropriation, directly or indirectly, has been conducted according to the principles of Fair and Equitable Treatment (FET). FET is determined through applying principles of (1) reasonableness, (2) consistency, (3) non-discrimination, (4) transparency and (5) due process. In this context, the legitimate expectations of an investor are taken into consideration in order to assess whether the state has expropriated in bad faith, through coercion, by means of threats or harassment. Due to the fact that there is no true harmonized multilateral dispute settlement system in relation to investment disputes, the interpretation and application of these principles are not uniform. Due to the confidential nature of arbitration, not all arbitration reports are public. The most concrete expressions of what legitimate investor expectations are can be found in statements made in published cases that seem to indicate that a balance must be struck.

For example, in International Thunderbird v. Mexico,Footnote 72 a NAFTA dispute conducted under UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, the panel held:

[A] situation where a Contracting Party’s conduct creates reasonable and justifiable expectations on the part of an investor (or investment) to act in reliance on said conduct, such that a failure by the NAFTA Party to honour those expectations could cause the investor (or investment) to suffer damages.Footnote 73

Conversely, in Saluka v. Czech Republic,Footnote 74 an investor–state dispute also conducted under UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, the panel held:

No investor may reasonably expect that the circumstances prevailing at the time the investment is made remain totally unchanged. In order to determine whether frustration of the foreign investor’s expectations was justified and reasonable, the host State’s legitimate right subsequently to regulate domestic matters in the public interest must be taken into consideration as well.Footnote 75

There are few ISDS cases involving IP.Footnote 76 These are cases that have been argued under the rules of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which is an independent branch of the World Bank.

First, there was a failed attempt at arguing a trademark infringement case under investor–state dispute settlement in AHS v. Niger.Footnote 77 In this case, although a concession to service Niger’s national airport had been terminated, there was continued use of seized equipment and uniforms bearing the trademarks of the complainant. The panel held that it had no jurisdiction, as IP enforcement is a civil matter that cannot be raised in the context of the ISDS expropriation complaint.

Second, there is the ongoing case of Philip Morris v. UruguayFootnote 78 that is argued under the Uruguay-Switzerland FTA,Footnote 79 and where the legitimacy of plain packaging tobacco products is challenged. In this case jurisdiction has been established and proceedings on the merits are to follow.

Third, there is a NAFTAFootnote 80 case argued under UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules. In Eli Lilly v. Canada,Footnote 81 pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly sought damages for $100 million CAD and challenged changes to the patentability requirements in respect of utility or industrial applicability, leading the Canadian patent office to invalidate two of Eli Lilly’s patents for the Strattera attention-deficit disorder pill and the Zyprexa antipsychotic treatment. Eli Lilly argued that the interpretation of the term ‘useful’ in the Canadian Patent Act by the Canadian courts led to an unjustified expropriation and a violation of Canada’s obligations under NAFTA on the basis that it is arbitrary and discriminatory. Canada conversely argued that Eli Lilly’s claims were beyond the jurisdiction of the Tribunal. Ultimately, in March 2017, the Tribunal dismissed Eli Lilly’s claims and confirmed that Canada was in compliance with its NAFTA obligations.Footnote 82

Cases involving IP can be and are clearly brought if measures negatively impacting upon the ‘investment’ can be attributed to a state that has submitted to ISDS. Issues such as IP enforcement or thresholds for patentability as such appear to be outside of the remit of ISDS, as these are civil or administrative matters where access to judicial review is usually provided. However, complaints over (arbitrary or discriminatory) denial of justice may not be. In the cases described above, one can argue that the general measures taken are neither of an arbitrary nor discriminatory nature. GI specifications, on the other hand, are discriminatory by nature since they are always specifically targeted, and this characteristic exceeds the already exclusionary nature of an IP right. This is because, as we have seen, the definition of the product comprises not only the product name and related labelling but also the description of the product, a definition of the geographical area, proof of the product’s origin, a description of the method of production, the linkage between the product and the area, the nomination of an inspection body empowered to police the specification.

This means that there are a number of actions that may have an immediate impact, not only on the existence and exercise of a GI, but also on its value and costs. The example of the Italian Prosecco DOC reformFootnote 83 comes to mind, as an enlargement of the geographical area, but also a possible reduction thereof has immediate effects for producers within and outside of the area. Production methods may also be subject to changes. Changes to production requirements resulting from a raise in food safety standards may be legitimized within the context of the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS).Footnote 84 Many of the GI production requirements are, however, steeped in a tradition and culture that solicit the demand for a particular product. If one, for example, orders Limburg Grotto Cheese,Footnote 85 one expects the cheese to have been ripened through completely natural processes by exposure of the cheese to the atmosphere of a limestone cave that contains the Brevibacterium Linens that produces a cheese with a pungent odour. The cheeses ripen on oak wooden boards and need to be turned regularly. This is a delicate operation as the fungi growing on the cheeses are poisonous. The result of food safety standards (no oak, stainless steel racks, etc.) has been that the traditional production for the traditional connoisseur consumer has now moved literally and figuratively underground. As a result, only the more industrial producers remain around to sell a product that is compliant with legal standards. They are selling a product that may be safer (although this is often disputed) but is certainly far less traditional than the consumer is led to believe. Phasing-out rules concerning slicing, grating, packaging, etc. stem from a desire to free the market from anticompetitive restrictions, but arguably these could also be measures that have a negative impact on the investments made by producers benefitting from GI specifications containing such rules. These forms of proprietary protection of GIs via individual regulations are also open to non-European entities, as we have seen above. So, a US association that holds an EU GI, such as the Idaho Potato Commission,Footnote 86 could then also sue before the special ISDS courts envisaged under the TTIPFootnote 87 for a weakening or strengthening of protection standards in Europe. In most cases, after all, the measure can be attributed to the state, and despite attempts by EU Member States to deny private parties the right to invoke international treaties, the CJEU has affirmed the direct effect of international treaties that bind the EU.Footnote 88

6 Conclusion

More than any other IP, a GI displays a very high level of state involvement in relation to specifications that do not directly concern the exercise of the IP right in terms of protection against consumer confusion and the like, but that very much influences the value of the GI for its owner. Definitions of territory, methods of production, sanitary and phytosanitary standards, and other more nefarious rules concerning slicing, grating, packaging, etc. can be changed at the behest of members of the consortium, but also of (semi-)state authorities or agencies. Insofar as these lead to a negative impact on members of the consortium, or third parties, there appears to be an increase in the options to challenge such measures under domestic constitutional and WTO rules, or bilateral and regional trade and investment agreements containing ISDS. These ISDS clauses are commonly included in recent US and EU trade and investment agreements, also those with Asian partners. To date, only a limited number of such cases that have been brought involve IP rights. The likelihood of success appears limited, but several key cases are still pending. In ISDS complaints over IP enforcement, tribunals seem hesitant to accept jurisdiction over these cases. In the plain packaging tobacco cases, the question will be the extent to which WTO Members have policy freedom in articulating exceptions to WTO obligations.

EU GI specifications are very targeted and individual in nature, so that any measure affecting them may be considered arbitrary or discriminatory much more easily as compared to general policy measures affecting the use, grant or scope of a trademark, design, copyright or patent right. Furthermore, many specifications are rooted in culture and custom rather than in science and utility, which raises the chances of a dispute over arbitrariness and discrimination in standards imposed when determining issues of culture and custom. Finally, measures affecting GI specifications are often attributable to a public authority or agency. This combination increases the likelihood of success of claims for protection of GIs as property and investments. If, for example, an EU company takes over (i.e., invests) a business located in Vietnam or Korea that is involved in the production of a GI product, and the Vietnamese or Korean authority redefines the geographical area in such a way that the EU company can no longer use that GI, this could give rise to an ISDS case. The same could be true for a US company making investments in Asian jurisdictions. This should be taken into consideration when drafting or changing GI product specifications.

1 Introduction and Structure

Asian countries are discovering geographical indications (GIs).Footnote 1 There are two reasons for this. First, the recognition that GIs can serve as an advantageous identifier for the marketing of domestic products abroad. Second, a system for the protection of GIs has become an obligation under bilateral and multilateral agreements. The question of how GIs from Asia can be protected abroad thereby becomes of interest. This chapter analyses how Asian GIs would fare in Europe.Footnote 2 ‘Would’, because as of yet there is very little actual experience in this respect. Very few GIs from Asia have been registered in Europe, be it as GIs or trademarks, and even fewer have been litigated. The examples used in this chapter demonstrate how ‘foreign’ GIs can, did or did not find protection in Europe, either at the level of European Community law or the domestic laws of individual European Union (EU) Member States.

This chapter is divided into four sections. Section 2 gives a brief overview of the interplay between social, economic and legal considerations when approaching the topic of protecting domestic GIs abroad. Section 3 discusses the possibilities for Asian GIs to obtain protection in Europe, be it under the sui generis protection offered by EU law or on the basis of bilateral or international agreements. Section 4 discusses protection under EU trademark law in different contexts: protection against registration of geographical names by third parties, protection based on trademark registration, protection based on the registration of a collective mark and protection once a trademark has received well-known status. Section 5 discusses non-proprietary protection in the context of unfair competition prevention law, namely as a guarantee of the ‘freedom to operate’ and market access.

2 Geographical Indications at the Crossroads of Culture, Law and Economy

Try to discuss GIs in a country with a strong heritage in food and beverages such as Italy, and tempers flare. Most consider it a huge injustice that Americans sell ‘Parmesan’ cheese that does not originate from Italy (and often tastes like grated wood), but would readily admit that neither ‘Parmesan’ nor ‘Parmigiano’ are protected indications in Italy itself (only Parmigiano Reggiano is). ‘Tokaj’ and ‘Prosecco’ are considered local indications by most Italians, yet few know or acknowledge that the fame of Tokaj is based on Hungarian Tokaj being sold to the Tsars of Russia, and even fewer know that ‘Prosecco’ is a place (let alone where it is on a map).Footnote 3 If they did, they would discover that this little village up the Karst region of Triest belonged to the Habsburg monarchy for almost 600 years, and the fame of the sparkling wine owes more to the Austrian Empire than to Italy. Particularly when it comes to national heritage and history, there is often a mismatch between local and global perception, and GIs are no exception. While for many, ‘Pilsener’ beer comes from Pilsen, ‘Budweiser’ beer from Budweis (Ceske Budejovice) and Bavarian beer from Bavaria, others take the view that ‘Pilsen’ is generic, ‘Budweiser’ comes from Anheuser Busch and Bavarian beer may come from Bavaria, or is generic, or may come from the Dutch brewery ‘Bavaria’. The same issues are discussed in the Asia-Pacific region. Australians strongly feel that ‘Ugg’ boots are Australian; Indians insist that ‘Basmati’ rice must originate from India (or, maybe, from Pakistan); and Thais feel the same about ‘Jasmine’ rice, while for many European consumers, these indications sound just as generic as Afghan dogs, bone China or Singapore Sling. Things are not helped by the fact that well-reputed indications often face an erosion from piggybackers: ‘Kobe beef’ produced in the United States and Australia is an example.Footnote 4