Everyone working in mental health services needs accurate and appropriate information to do their jobs well. However, established information systems and information departments have apparently consistently failed to provide this. One of the main difficulties for information departments is the diversity of information needs within the service. Crudely put, although clinicians are more interested in information about their patients, managers and commissioners appear more interested in information about clinicians and clinical activity. Unable to fulfil both these needs, there is a tendency (perhaps inevitable) for information departments to concentrate on the needs of managers and commissioners at the expense of clinical needs. The result is tension within information systems. Clinicians are often resentful about having to provide raw data to fulfil what seems like the obscure demands of management. Perhaps because of this, the information supplied to commissioners is often inaccurate and incomplete. In short, when it comes to information, nobody is happy.

This paper describes an attempt to overcome this information deadlock through a compromise in terms of what is collected and for whom.

Method

Members of the Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham health authority's commissioning team began meeting in 1996 with clinicians and information managers from the local mental health trust. The overarching aim was to construct a single information model that first supports clinical governance — helping to “ensure that… evidence based practice is in day-to-day use” (Department of Health, 1997, p. 47); second, shifts the emphasis of service commissioning from cost towards “evidence of increased cost effectiveness in delivering mental health services” (Department of Health, 1999, p. 4); and third, uses information that can be feasibly collected in day-to-day practice.

In very broad terms, a patient-based model to investigate ‘what works best with whom?’ was constructed. This meant describing and categorising three axes of information: the underlying problem or need of the patient; the intervention or what is done; and the clinical outcome — does the patient get better?

To categorise ‘problem’, full ICD—10 diagnosis was considered infeasible as it can be difficult to collect the necessary information (Reference Glover, Knight and MelzerGlover et al, 1997). Categories were based on ICD—10 (World Health Organization, 1992) but those that all clinicians can apply were therefore used. In analysis these categories were collapsed into ICD—10 chapter headings.

To measure severity, and ultimately outcome, Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS) (Reference Wing, Curtis and BeevorWing et al, 1996) and its variant HoNOS for elderly people (HoNOS65+) (Reference Allen, Bala and CarthewAllen et al, 1999; Reference Burns, Beevor and LelliottBurns et al, 1999) were selected because they form part of the mental health minimum data-set and are consequently recommended in the National Service Framework (Department of Health, 1999).

In categorising interventions, a detailed description can be open to variations in interpretation in different parts of the service (Reference Carthew and PageCarthew & Page, 1999). A practical list of generic intervention categories applicable across the whole service was developed, focusing primarily on intensity (Reference CliffordClifford, 1993).

Two older adult sites — a community mental health team and acute ward — and an adult case-management team took part in a 9-month pilot. Each site was already routinely recording HoNOS/HoNOS65+. During the pilot, problem and intervention were routinely recorded as part of established HoNOS assessments. Two specific hypotheses were tested:

-

(a) Accurate data can be reliably collected — the reliability of ‘problem’ entries was tested. Two or more entries made for the same patient across the pilot period — normally made by the same rater — were compared. Planned interventions were categories at each assessment. Accuracy was tested by comparing the number of contacts planned to the number that actually took place — recorded on a local electronic system and in case notes.

-

(b) The model produces relevant evidence to investigate clinical practice — critical to both clinicians and commissioners, it was assumed that collecting accurate data in the long run would only be feasible if the information could be of direct use to those having to provide it. To evaluate the potential of the model to inform evidence-based practice, data were analysed and routinely fed back at participating sites, and views were sought on their utility.

Results

Reliability of ‘problem’

‘Problem’ remained consistent across a series of assessments for both adult (κ=0.87, P<0.001, n=67) and older-adult cases (κ=0.79, P<0.001, n=161).

Were contacts predicted accurately?

There was a positive correlation between the number of contacts predicted and those recorded electronically (r=0.79, P<0.001, n=22) and in case notes (r=0.59, P<0.001, n=29).

Did the model produce evidence with the potential to inform practice?

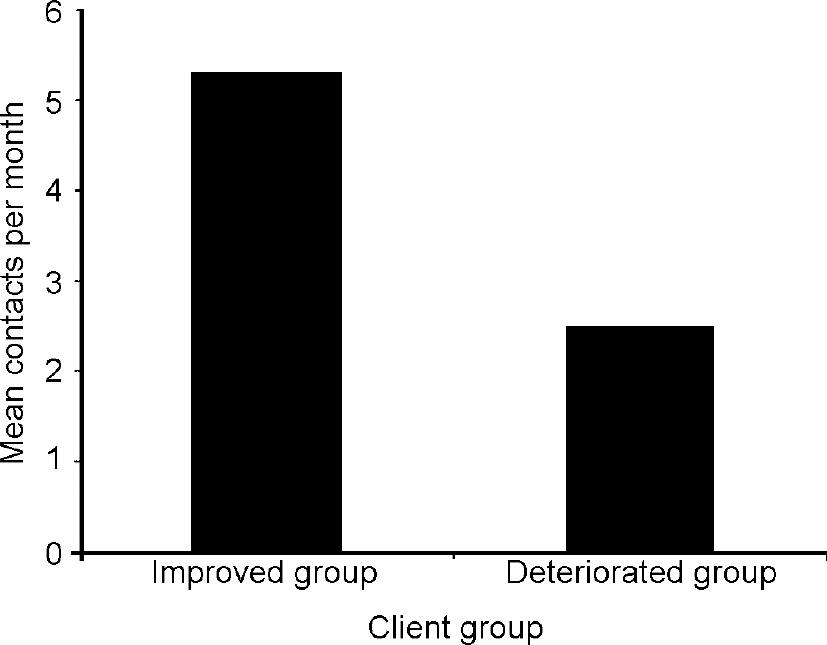

By the end of the pilot period reports indicating which patients had best/worst outcomes and how these were related to the intensity of intervention was being generated. For example, at one site 15 clients with an organic mental disorder (F0; World Health Organization, 1992) had been referred and discharged during the pilot period. HoNOS65+ scores showed eight had improved and seven deteriorated. Apparently related to intensity of intervention, the ‘improved’ group had received more than double the amount of contacts than the ‘deteriorated’ group (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The number of contacts per month planned for different outcome groups

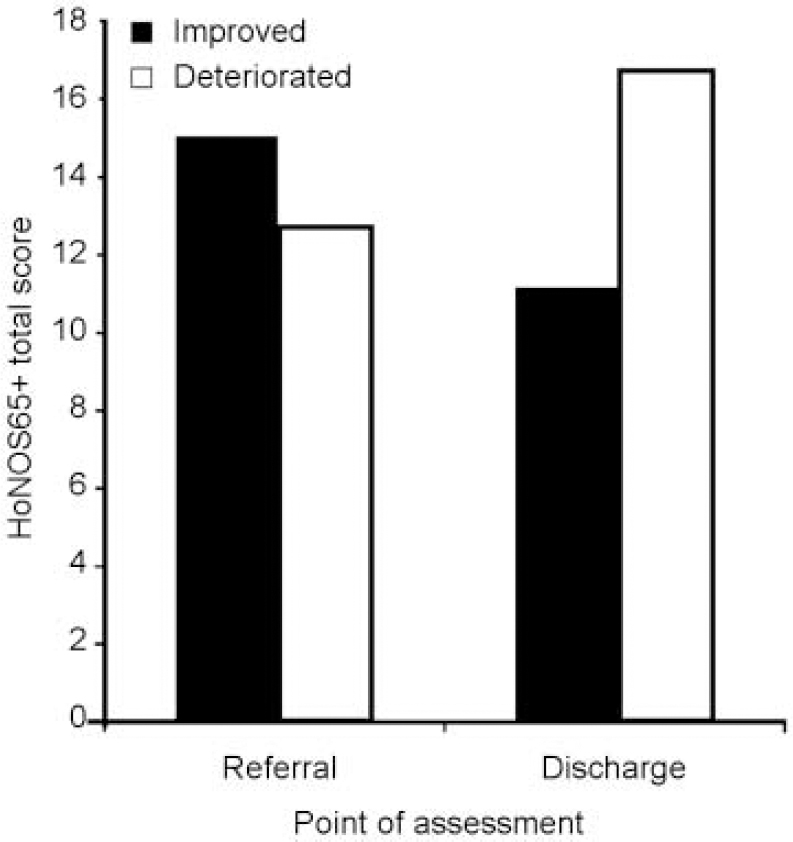

Fig. 2 Mean Health of the Nation Outcome Score for elderly people scores (HoNOS65+) at referral and discharge for two client groups.

Why is one client offered more contacts than another? Mean HoNOS65+ scores at referral showed that the ‘high contact’/‘better outcome’ group had presented with greater severity. However, at discharge, rather than converging, the score differential for these two groups increased. The ‘deteriorated’ group ended up worse off than the others had been at referral. The ‘improved’ group ended up better off than the others had been at referral.

This result begged an obvious question — paradoxically, for clients with an organic disorder is it better to be worse at referral? Within the team, heated debate ensued. They concluded, sample-size aside, that independent variables such as age, onset etc. needed investigation before validly answering this question.

After similar reports, clinicians at all sites agreed the information was ‘potentially’ useful. Rather than providing firm conclusions it has the potential to highlight relevant questions and direct evidence-based debate about best-practice. As a concrete representation of this, participants volunteered to continue data collection after the pilot period was over. However, continued data collection was contingent on two explicit conditions:

-

(a) results continue to be fed back to the teams on a regular basis

-

(b) HoNOS/HoNOS65+ training is provided on a regular basis to help ensure interrater reliability.

Discussion

An evaluation of the clinical response to this information is descriptive and no formal methodology has been used to measure this. Nonetheless, in agreement with the clinical teams taking part, the overall conclusions of the pilot were that accurate data can be provided reliably and the model can usefully inform clinicians about best practice. Significantly though, participating clinicians were keen to add two provisos to these conclusions. First, as the conditions for continued data collection imply, long-term collection of accurate data is dependent upon the provision of direct and appropriate support, for example, feedback and training. Second, in this context the intervention categories used were potentially of some use, but were of little value in day-to-day practice. Categories differentiating between interventions of more clinical relevance as well as intensity would not only elicit more interesting results, but independent of this model, would be more relevant to practice.

The second of these is not a surprise. Evident from the focus on intensity of intervention — of more interest to commissioners than clinicians — this model is rooted in compromise. Ironically though, perhaps the strength of the model lies in this compromise. Based on past experience many are cynical that the kind of support recommended for long-term collection will ever be delivered. However, in this case, there is a direct and practical incentive for commissioners, managers and therefore information departments to provide exactly the kind of support required — namely, they want this information as well. As direct evidence of this in practice, both the local health authority and the NHS information authority continue to directly fund this project, even though it is now focused on providing the kinds of support (e.g. feedback and training) and development (e.g. of intervention categories) requested by clinicians.

Conclusion

Although demands are made on clinicians to feed current information systems, they appear to get little in return for this effort. While still in its infancy, this model is a good example of how information systems and procedures can evolve to ensure better provision of relevant information to all concerned. This is an essential development if information about the service is to serve its proper purpose — to help improve patient care.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to members of all participating clinical teams and members of the project Steering Group, including: Professor Alastair MacDonald (Guy's, King's and St Thomas' School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences); Mr Mike Denis, Dr Dinshaw Master, Dr Anula Nikapota and Dr David Roy (South London and Maudsley NHS Trust); Dr Richard Carthew (The NHS Information Authority); and Mr Doug Adams and Mr Anil Yogasundram (Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham Health Authority).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.