INTRODUCTION

During 2013, US state and local public health officials, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigated large numbers of US cyclosporiasis cases [1]. During June–August 2013, 631 laboratory-confirmed cyclosporiasis cases were reported from 25 states in persons with no history of travel outside the United States or Canada within 14 days before illness onset. A total of 49 ill persons were hospitalized and no deaths were reported [2]. An investigation in Texas implicated cilantro originating from Pueblo, Mexico as causing illnesses in persons reporting patronage of a Mexican-style restaurant in Fort Bend County, Texas (i.e. Houston metropolitan area) [1]; illness onsets of 25 cases ranged from 10 to 24 July 2013 [Reference Abanyie3]. A Nebraska and Iowa investigation that focused on a common producer and distributor used production, shipping, and delivery information to link illnesses to the romaine component of a salad mix containing iceberg and romaine lettuce, red cabbage, and carrots. This product was served as the only house salad lettuce-mix ingredient in two restaurant chains (A/B) sharing a common parent company [4, Reference Buss5]. Overall, 169 cyclosporiasis cases were identified in persons who reported exposure at 26 regional chain A/B restaurants, including 71% of all cases identified in Iowa and Nebraska [Reference Buss5]. A single production lot code (PC) and common-origin growing field (PC-T; grower R/ranch R/lot R) were identified as the source of contaminated romaine lettuce that probably caused cyclosporiasis in chain A/B restaurant patrons reporting illness onset during 11 June–1 July 2013. Epidemiological work from this initial investigation also suggested that romaine lettuce from both a related growing field and a third, seemingly unrelated field might have caused other cases with reported illness onsets both prior to and after the defined time period of exposure for the majority of cases, respectively [Reference Buss5].

Despite the aforementioned findings and knowledge that potentially contaminated romaine lettuce likely entered US food supplies for widespread distribution, large numbers of unexplained US cases remained in Nebraska, Texas, Florida, and elsewhere [1]. Accordingly, the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services convened a multistate investigation with Texas and Florida – both had higher numbers of cases compared to other states – to identify persons with cyclosporiasis who might have had common exposures to romaine lettuce products [Reference Buss5] traced forward from previously implicated Mexico fields-of-origin to US points-of-service.

METHODS

Case-finding

We defined state-specific case numbers to study temporal commonalities across regions. Standardized, structured questionnaires used in Nebraska and Iowa focusing on produce and restaurant exposures ⩽14 days before onset had also been administered to Texas and Florida residents confirmed with illness [Reference Buss5]. A cyclosporiasis case was defined as laboratory-confirmed Cyclospora infection in a person with symptom onset from 1 June–31 August 2013 with no travel history outside of the United States or Canada during the 14 days prior to illness onset.

Grower ranch lot-level and production-code-specific traceforward investigation

Producer A romaine lettuce from two Mexico-origin single-grower ranch lots previously implicated in the Nebraska/Iowa regional investigation [Reference Buss5] was traced forward to define entirety of US distribution for comparison to national distribution of ill persons. All names used herein to list growers, the producer, distributors, and lot codes of various shipments have been anonymized. Figure 1 gives an overview of the potential product flow from Mexican growing fields to ultimate US points-of-service and serves to introduce and orient readers to the multiple anonymized names referenced herein. For affected states, we collaborated with CDC to establish case numbers with symptom onset during 1 June–1 July 2013 – a time period consistent for contemporaneous potential exposure to romaine lettuce products from these common fields-of-origin.

Fig. 1. General overview of the possible distribution channels* by which potentially contaminated producer A romaine lettuce-containing salad products were supplied from Mexico-origin growers and fields (growing lots) through distributors X†, D, or P to locations reported by persons ill with cyclosporiasis – multiple US states, May–June, 2013. (* This flowchart is provided only as an overview of the various growers and distribution channels described herein. Accordingly, the channels depicted are not intended to demonstrate product movement from a specific grower to any specific final end point-of-service. † Distributor X did not have a single physical location. The product was delivered directly to this company's various distribution hubs by producer A.)

Given known shipping dates and 14-day shelf-life, grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine-containing products were likely not served before 5 June and possibly served up to 17 June [Reference Buss5]. Accordingly, illnesses in other states potentially associated with such common-source romaine would likely have had onset dates in a similar time period as established for associated cases in Iowa and Nebraska, i.e. 11 June–1 July 2013 [Reference Buss5]. Thus, we compared national distribution of confirmed ill persons with onsets in this time period to grower-specific US distribution information for producer A shipments of grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine. We also performed similar comparison for earlier romaine shipments to Texas and Florida from previously implicated grower R/ranch R/lot Q [Reference Buss5]. Within the producer A data, for a small proportion of blended product shipments having iceberg lettuce as the primary ingredient, the romaine grower was unknown. For these, we assigned a grower name using romaine-grower information predominating in the other romaine-only or romaine-containing salad-blend products processed on the same day, shift, and production line (i.e. same production lot code).

To study unexplained illnesses in Nebraskans, we defined all Nebraska distributor X delivery locations that received grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine lettuce. Upon identifying these points-of-service, we reviewed available exposure data for 18 confirmed ill Nebraskans who reported illness onset during 11 June–1 July 2013 and no chain A/B exposure. We re-interviewed these persons during December 2013 aiding further recall by listing all known points-of-service.

Ethical approval

The investigative activity reported herein underwent CDC human participants review and was determined to be public health practice and not research; as such, Institutional Review Board approval was not required.

RESULTS

Nationwide traceforward investigation of grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine lettuce

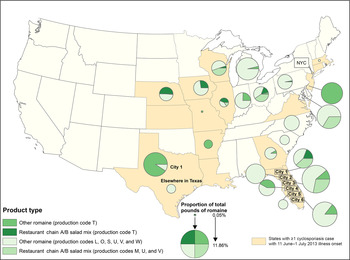

Nationwide, the entire reported production volume (100%) of grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine lettuce supplied by producer A was shipped 2–6 June to 26 distributors in 18 central and eastern US states (Table 1, Fig. 2). In these regions, 324 confirmed ill persons with illness onset during 11 June–1 July were identified (Fig. 3). Of these, 97% (314/324) resided in 11 states receiving approximately 66% of this one lot's romaine production; 3% (10/324) resided in immediately adjacent states where distribution of potentially contaminated product possibly crossed state borders. Of all PC-T salad products containing romaine lettuce (20% chain A/B salad mix; 80% other, Table 1), 91% originated from grower R/ranch R/lot R. Of this product, labelling descriptions suggested 70% was bound for chains A/B or C; the remainder had producer A product description but lacked information to ascertain final destination points-of-service.

Fig. 2. US distribution of producer A romaine or romaine-containing lettuce products from grower R/ranch R/lot R by proportion of overall total poundage*, product type, and production code†, 2–6 June 2013‡. [* ‘Overall total’ represents the entire volume (100%) of processed romaine lettuce products from grower R/ranch R/lot R including all production code T product shipped by producer A from 2 to 6 June 2013 to multiple distributors in 18 central and eastern US states. † Texas and Arkansas both received small volumes of production code T product included in the overall total which contained romaine lettuce not originating from grower R/ranch R/lot R (2·4% of ‘overall total’ in approximate equal volume in both states). However, this product did share the same production line and shift and potentially shared pre-processing wash water thus potential for cross-contamination existed. ‡ Product distribution as depicted herein is not intended to represent any specific geographical locations of either distributors or cities within the states in which they are located.]

Fig. 3. US distribution of cyclosporiasis cases with 11 June–1 July 2013 illness onset by state (N = 324).

Table 1. Percent of overall total (100%) of producer A US distribution of grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine or romaine-containing lettuce products by production lot code and product type, 2–6 June 2013

PC, Production lot code.

* Numbers in the ‘Percent of each PC in overall total’ column represent the PC-specific proportion of the overall total volume (100%) of grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine or romaine-containing lettuce products processed and shipped by producer A from 2 to 6 June 2013.

† Numbers in each row represent the proportion of the various product types out of the total volume for each PC (i.e. denominator = volume represented as percent in the corresponding ‘Percent of each PC in overall total’ column).

‡ Texas and Arkansas both received production code T (PC-T) product which contained romaine lettuce not originating from grower R/ranch R/lot R (9% of all PC-T product in approximate equal volume in both states). However, this product did share the same production line and shift and potentially shared pre-processing wash water thus potential for cross-contamination existed.

Case-finding

In Texas, 270 confirmed ill persons were identified of whom 265 (98%) were interviewed; 150 (56%), 74 (27%), and 46 (17%) were residents of city 1, the Houston metropolitan area (illness onsets after 8 June), and other areas, respectively (Fig. 4). Of the ill Texas city 1 and Houston area residents, 134 (89%) reported onsets on or before 12 July and 64 (86%) reported onsets after 12 July 2013, respectively. In Nebraska and Florida, 87 and 33 confirmed ill persons were identified (Fig. 5); all were interviewed.

Fig. 4. Confirmed cyclosporiasis cases by reported date of onset and location of residence (N = 270), Texas, June–August 2013. (* Three Texas cases depicted with illness onsets prior to 8 June 2013 are reported as residents of ‘All other areas in Texas’ and not the city 1 metropolitan area; this distinction potentially includes Houston metropolitan area residents. For Texas cases occurring after 8 June, residents of the Houston metropolitan area and ‘All other areas in Texas’ are enumerated and represented accordingly.)

Fig. 5. Confirmed cyclosporiasis cases by US state of residence, reported date of onset, and reported exposures, June–August 2013. [* Restaurant chain C exposure. † Three Texas cases in residents of two metropolitan areas other than city 1 (not included in Texas city 1 case count, N = 150).]

State-specific traceforward investigation

Texas and Florida traceforward investigation

Texas city 1 distributor D supplied grower R/ranch R/lot R chopped romaine lettuce (PC-T) to three chain C restaurants each patronized by one confirmed ill, salad-consuming person. Of these, two had two chain C exposures each during 9–11 June and both reported illness onset on 20 June. The third chain C patron reported illness onset on 19 June but did not provide an exact exposure date. On 3–4 June 2013, producer A had shipped PC-T and PC-L chopped romaine lettuce to distributor D, harvested on 2 June from grower R/ranch R/lot R and packaged with the chain C parent company label (company B); 6% of these product boxes were delivered on 5 and 7 June to the three chain C restaurants. The remainder was likely dispersed by distributor D among other city 1 metropolitan area chain C locations. Of 150 confirmed ill city 1 area residents, 62 (41%) reported illness onset during 11 June–1 July 2013. Of these, 15, including the aforementioned three reported exposures to 12 area chain C restaurants, all of which had likely served common field-of-origin distributor D-supplied PC-T or PC-L chopped romaine. On 3–4 June, four production codes of grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine were also shipped into Texas under other varying labels (not company B). City 1 distributor D handled most of this product while the remainder went elsewhere in Texas (Fig. 2); labelling descriptions did not yield clues to define destination points-of-service.

Multiple boxes of PC-T salad mix were shipped on 3 June to Florida city 1 distributor P who delivered these to chain A/B restaurants on 7–8 June. Two confirmed ill persons with 15 and 19 June onset dates reported dining and consuming salad in chain B and A restaurants on 8 and 14 June, respectively. Elsewhere in Florida, grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine lettuce was received by four distributors for subsequent chain A/B delivery (Fig. 2); five additional confirmed ill persons reported dining at chain A/B restaurants within the likely service areas. Beyond chains A/B, grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine with company B labelling was received by three distributors; approximately one third went to Florida city 4 where one ill person reported chain C exposure. Altogether in Florida, distributors in six cities handled 38% of the total US volume of producer A-supplied grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine (Fig. 2), most was shipped on 3 June 2013; five production codes (L, S, T, U, V) were represented. Five of these six distributors were in geographical locations consistent with county of residence of all 18 confirmed ill Florida residents with 11 June–1 July onset.

In three Texas and three Florida metropolitan areas, nine and three residents reported illness onsets on or before 8 June, respectively (including Texas city 1, n = 6). In each of these locations, distributors had received producer A shipments on 27–28 May 2013 of romaine lettuce from grower R/ranch R/lot Q, the field-of-origin of romaine lettuce that was linked to two Iowa cases with illness onsets before 9 June [Reference Buss5]. Four additional Nebraska residents (two reporting chain A/B exposure) also reported illness onsets before 8 June and all resided within the service area of the distributor X Nebraska hub which had also received grower R/ranch R/lot Q romaine [Reference Buss5]. Such early onset cases initially seemed to be outliers when investigated in context with larger numbers of later-onset cases, so limited exposure information was captured. Accordingly, no information to link such confirmed ill persons directly to receiving points-of-service was available. Notwithstanding, romaine lettuce harvested on 26 May from grower R/ranch R/lot Q was shipped as blended or chopped romaine with various non-descriptive product labels to Texas and Florida distributers that served areas near the residences of all 12 confirmed ill persons in these states with illness onset on or before 8 June.

An additional, large volume of grower R/ranch R/lot Q romaine lettuce was harvested on 26 May and shipped in bulk bins in equal volumes to producer A retail production centres in Texas, Florida, and Tennessee; information was lacking to define handling and processing. In Tennessee, no June onset cyclosporiasis cases were identified and no other grower R romaine-containing products were known to ship to that state from producer A's processing facility.

Nebraska traceforward investigation

From 8 to 11 June 2013, distributor X supplied producer A chopped romaine lettuce (PC-S, grower R/ranch R/lot R) from its Nebraska hub to 48 separate points-of-service including restaurants, convention centres, vending suppliers, and multiple cafeterias (e.g. worksites, hospitals, colleges) in Nebraska, South Dakota, and Iowa. Of 18 confirmed ill Nebraskans not reporting chain A/B exposure (11 June–1 July onset), 16 were successfully re-interviewed; four recalled previously unreported exposure 2–14 days prior to their illness onset, each in one of 48 known points-of-service. Of these, three recalled lettuce consumption but could not report lettuce type or exact exposure dates; one could neither confirm nor deny lettuce consumption.

Summary of state-specific traceforward results

Upon completion of the aforementioned traceforward investigations, 82 confirmed ill persons (Nebraska, n = 57, including 51 previously reported [Reference Buss5]; Texas city 1, n = 17; Florida, n = 8) were identified with onsets during 1–8 June (n = 4) and 11 June–1 July (n = 78) and likely exposure to romaine lettuce from two common-origin growing fields (grower R/ranch R/lot Q and lot R, respectively) served in chain A, B, or C restaurants, or other points-of-service (Fig. 5). Upon review of completed interviews administered to confirmed ill persons in other states with onsets on or before 11 July, no additional exposures to chains A/B, or C were identified. Outside of Nebraska, Iowa, Texas, or Florida, only one other domestically acquired outbreak-associated case of illness was reported with onset before 11 June [i.e. 10 June (CDC, written communication)]. Eight Texas city 1 metropolitan area residents and two Nebraskans with illness onsets after 1 July 2013 also reported chain C and A/B exposures, respectively (Fig. 5). Later harvested romaine lettuce from a grower other than grower R (i.e. grower Y/ranch Z/lot S) which likely caused illnesses in Iowa [Reference Buss5] had also been shipped contemporaneously to Texas and Nebraska distributors near residences of these ill persons (and also to Florida); however, distribution information to definitively link exposure at points-of-service to later-occurring illnesses was lacking.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that producer A-supplied romaine lettuce from one growing field (grower R/ranch R/lot R) was the likely source of cyclosporiasis in 78 persons in Nebraska (n = 55, 51 previously reported [Reference Buss5]), Texas (n = 15), and Florida (n = 8) with illness onsets during 11 June–1 July 2013 who reported exposure in chain A/B or C restaurants, or other points-of-service. Our findings further suggest grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine lettuce as a vehicle for infection when combined with other reported findings; same field-of-origin romaine lettuce was also linked to 111 cases with 11 June–1 July onset in Iowa (n = 105), Wisconsin, (n = 3), Kansas (n = 2), and Missouri (n = 1) in chain A/B patrons [Reference Buss5]. Overall, these combined findings demonstrate that the 2013 harvest from this single field likely caused 189 cyclosporiasis cases in seven states. In ultimately defining producer A's national distribution of grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine lettuce, our findings further suggest this product as a possible exposure for the remainder of all 324 confirmed ill persons (n = 135) with illness onset during 11 June–1 July 2013 throughout 18 central and eastern US states.

Our findings further suggest that a presumably adjacent field (lot Q) – having a sequential identifying number compared to grower R/ranch R/lot R – is a plausible source for 16 earlier-occurring cyclosporiasis cases with illness onset on or before 8 June in Texas (n = 9), Nebraska (n = 4), and Florida (n = 3). Two additional Iowa cases with onset on or before 8 June were previously reported with well-established grower R/ranch R/lot Q romaine exposure in chain A/B restaurants; and two others had plausible exposure [Reference Buss5]. Romaine lettuce from this field was distributed in each of the respective areas in Texas, Florida, Nebraska, and Iowa where all of the aforementioned cases occurred. With these combined findings, we ultimately demonstrate that all 20 US residents identified with illness onsets on or before 8 June 2013 plausibly shared this common romaine field-of-origin exposure across four states on the basis that they all resided in geographical areas where this product was distributed.

Of 270 confirmed ill Texas residents, the majority resided in the city 1 and Houston metropolitan areas. Two distinct peaks depicted in Figure 4 demonstrate that at least two outbreaks likely occurred in Texas. This finding is consistent with previous reports of least two 2013 outbreaks associated with different food vehicles originating from Mexico [1, Reference Abanyie3]. Of the confirmed ill Texas city 1 metropolitan area residents, 89% reported onset on or before 12 July 2013. Whereas in Houston, the large majority of ill residents reported onset after 12 July 2013. Cilantro originating from Pueblo, Mexico was implicated as the cause of later-occurring illnesses in 25 patrons of a Mexican-style Houston area restaurant among whom the earliest reported onset date was 10 July 2013 [1, Reference Abanyie3]. Additional investigative and traceback findings reported from Texas also demonstrated Pueblo, Mexico as a shared source of cilantro served in restaurants elsewhere in that state and possibly causing 13 additional cases [Reference Abanyie3]. We hypothesize that cilantro from Pueblo, Mexico might have caused some later-occurring city 1 area illnesses but likely not the majority given the clear depiction in Figure 4 of two distinct outbreaks. Further, cilantro is also an unlikely source of earlier-occurring illnesses elsewhere in the United States (i.e. those with reported onset on or before 1 July 2013).

Given the herein defined distribution channels for producer A romaine lettuce and findings from the Nebraska and Iowa investigation [Reference Buss5], we hypothesize that common-source romaine lettuce from a grower other than grower R (harvested/shipped later) was likely distributed contemporaneously to points-of-service in Texas, Nebraska, Florida, and Iowa – all four states had unexplained cases in the same time period. Such a scenario provides a unifying theory to link a large proportion of 1–12 July onset cases to widely distributed, common-source products besides cilantro from Pueblo, Mexico, a product not linked to illnesses beyond Texas nor traced forward to any other states. No information currently exists to establish if irrigation water or other potential contamination sources might have been shared by another grower besides grower R. Further retrospective investigation in these states could define distribution of romaine from grower Y/ranch Z/lot S, the grower possibly associated with later-onset cases in Iowa [Reference Buss5]. Additionally, existing exposure information already captured from persons experiencing later-onset illnesses could be retrospectively studied focusing on out-of-home lettuce exposures, particularly in the Texas city 1 area where the largest case numbers are evident (Fig. 5). Such investigation holds promise to solidify romaine lettuce as causing the majority of 2013 US cyclosporiasis cases with onsets in June and early July.

Given previously reported findings suggesting pre-harvest contamination of multiple fields from seemingly unrelated growers [Reference Buss5], our findings invite questions regarding romaine production practices. Grower R supplied large volumes of iceberg lettuce to producer A from ranches other than ranch R [Reference Buss5]. Unfortunately, no information was available to establish proximity to ranch R/lot Q or lot R romaine growing fields. We hypothesize that iceberg lettuce grown in other grower R ranch lots might have been subjected to similar pre-harvest environmental conditions as romaine, yet grower R iceberg lettuce was not linked to June-onset illnesses [Reference Buss5]. Further, the FDA's environmental assessment did not identify any significant potential sources of the pathogen or route of contamination to iceberg lettuce [6]. Research is needed to establish if romaine lettuce might be inherently more susceptible to contamination or carriage of C. cayetanensis oocysts compared to iceberg lettuce or if differing romaine-specific irrigation or other production practices might also offer plausible explanations. Investigation of grower R's practices is also indicated to determine if differing harvest practices existed for romaine lettuce bound for processing compared to product presumably harvested in bulk and possibly shipped direct from the field. An apparently large volume of same field-of-origin romaine lettuce was bulk-shipped to Tennessee yet no June-onset cases were identified there. Further study is indicated to determine why, in comparison, same-field romaine lettuce bound for processing seemingly had more likelihood of subsequently causing cyclosporiasis upon consumption.

Despite such potential differences with production and harvest, we are further intrigued by the fact that grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine lettuce appears to have caused a substantially and disproportionately higher number of illnesses compared to same-ranch lot Q romaine. Further investigation of grower R's practices could yield more information. In the interim and on the basis of our observations and insights, we offer plausible explanations. First, perhaps difference in timing of harvest was a factor; lot Q romaine was harvested on 26 May while lot R was harvested later on 2 June. Perhaps environmental factors somehow led to more contamination affecting the later harvest (e.g. differential exposure to contaminated irrigation water or rainwater runoff). Second, perhaps a higher number of earlier-occurring illnesses did indeed exist but were simply missed by surveillance for unknown reasons. Finally, perhaps environmental conditions between harvests changed to differentially favour formation of infective oocysts for contamination of the later harvest. Little information exists to fully understand the environmental factors that allow C. cayetanensis to become infective [Reference Ortega and Sanchez7, Reference Chacin-Bonilla8] and we are unable to provide definitive explanations for these observed differences.

Our findings are subject to certain limitations. Patient interviews were generally conducted much later than ill persons' potential exposures. Such time delays might have adversely affected recall accuracy thus limiting information to define exposures, particularly for patients not reporting chain A/B or C exposures. With regard to finding common exposures in ill persons throughout the nation, the expansive distribution of potentially contaminated product to large numbers of seemingly unrelated points-of-service represents an unsurmountable epidemiological challenge in the absence of accurate distribution-level data. For example, the Nebraska distributor X hub alone handled only 3% of all US-distributed grower R/ranch R/lot R romaine lettuce, but this relatively small volume went to 63 points-of-service (15 chain A/B, 48 other venues). Elsewhere nationwide, the remainder of production from this field was distributed to an undoubtedly vast but unknown number of venues. As such, we are unable to estimate a proportion of all US cases attributed to product from this field. With regard to product tracking, no processes existed to define timing of production at producer A's processing facility for individual boxes of product within given days, shifts, and production lines. Thus, delivery- and code-specific information was lacking to link individual shipments to subsequent illnesses given the possibility of differential contamination levels. To further challenge such tracking, few systems existed to track individual product through vast distribution channels to ultimate points-of-service. Thus subsequent targeted traceforward investigation and focused, corresponding case-finding were precluded.

Our findings demonstrate that Mexican-origin, processed romaine lettuce supplied by producer A from two single-grower ranch lots likely caused a large cyclosporiasis outbreak with cases occurring in the eastern half of the United States during June 2013. Romaine from at least one additional grower is the likely cause of later-occurring illnesses in Iowa and possibly elsewhere [Reference Buss5]. Production practices employed by these growers should be investigated to determine potential sources of contamination and to develop prevention recommendations. Further, investigation should be expanded to include practices of adjacent growers as indicated if potential common sources of contamination such as shared irrigation water existed. Finally, to aid future outbreak investigations, the produce and food service industries should adapt processes to track and maintain shipping records for individual boxes of product from field-of-origin to processing facilities completely through supply channels to ultimate points-of-service.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully thank Karis Bowen for GIS support, Dr Anne O'Keefe for graphics design, and Rebecca Hall (CDC) for collaboration with national case-finding. We also thank our colleagues in the Nebraska Public Health Laboratory and Nebraska Department of Agriculture for their substantial contributions. Further, we thank the large number of professional colleagues who collaborated extensively in this investigation within our own agencies; in Nebraska, Florida, and Texas local health departments; in all states throughout the nation where cases of illness were identified; and at CDC and FDA. Finally, we thank the healthcare providers and clinical laboratories throughout Nebraska, Florida, Texas, and elsewhere in the nation for their vigilance and diligence in diagnosing and reporting cyclosporiasis cases as reported in this paper; all the restaurants, their parent companies, the producer, and distributors for cooperating fully with our investigation and providing all requested and necessary product distribution information to facilitate traceback and traceforward efforts; and all ill persons who provided information regarding their illnesses and exposures upon being interviewed.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Likewise, the authors' findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, Florida Department of Health, or Texas Department of State Health Services.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.