Socialisation: Competitive or cooperative?

The concept of international socialisation occupies a central place in the contemporary debate on rising powers and global order. In recent years, however, scholars have increasingly problematised the conventional framing of socialisation as unidirectional norm diffusion where superordinate actors ‘educate’ subordinate actors. For example, Alastair Johnston shows that China and the United States both contest and conform to different aspects of the liberal international order,Footnote 1 rendering it difficult to determine who is socialising whom. Socialisation can be a ‘two-way process’,Footnote 2 or a ‘reciprocal’ phenomenon,Footnote 3 as noted by Amitav Acharya, who presents instances where rising powers and non-Western states influence ideational developments in the hegemonic West.Footnote 4

Building on these critical reflections, this article develops an alternative approach to international socialisation that takes seriously the agency of subaltern actors. The dominant strand of socialisation research in IR draws from Parsonian sociology, where socialisation is conceived as a status-quo-oriented practice that reinforces the existing power hierarchy.Footnote 5 This has resulted in a one-sided theory neglecting the importance of endogenous and self-directed socialisation efforts embarked upon by subaltern actors. In light of this, the present article develops an alternative concept of competitive socialisation through which subaltern actors strengthen their capacity, agency, and legitimacy. By internalising dominant norms, subaltern actors can enhance their competitive edge, enact more equalised power relations, seek greater international status, and challenge Western primacy in global politics.

This article innovates theoretically in three ways. First, based on macro-historical reflections on the experiences of non-Western states, the article shows that Westernisation can be pursued as a means to challenge Western primacy. Put differently, ‘norm-taking’ is not always an act of submission; it can also be an act of subversion and revision. Second, we develop a new typology of norm diffusion that takes into account different types of power relations. This typology enlarges the scope of research on socialisation, norm diffusion, rising powers, and global order transformation and thus stimulates further research. Third, the article demonstrates that competitive social relations can induce deep internalisation of dominant norms even in the absence of ‘we-feeling’. We demonstrate this empirically through the cases of Chinese socialisation into the peacekeeping community and Russia's socialisation into the multilateral development community. The case studies show that rivalry with Western powers prompted China and Russia to modify their prior attitudes and adopt the dominant norms to gain a more competitive edge and a greater international status in global politics. This, in turn, resulted in fundamental changes in their behaviours from initial norm rejection, to passive acceptance, and finally to active learning and norm internalisation.

Following this introduction, the second section of this article presents a critical review of IR research on norm socialisation, problematises the conformist bias in IR socialisation research, and develops the alternative concept of competitive socialisation. The third section situates competitive socialisation in a wider spectrum of norm diffusion processes and elaborates how the concept can be operationalised. The fourth section applies this framework to the Chinese and Russian cases and shows that the holistic internalisation of Western norms has enabled Beijing and Moscow to challenge the existing global power hierarchy, understood as an international social order of status, prestige, and recognition. The final section concludes with reflections for further research.

Socialisation beyond the global hierarchy

Though the concept of socialisation is most often associated with social constructivist research programmes, it was neorealists who led the initial incorporation of the concept into in contemporary IR theory. In his Theory of International Politics, Kenneth Waltz theorised that socialisation is the main mechanism through which ‘like-units’ come to resemble each other.Footnote 6 In line with this, the neorealist socialisation theory stipulates that ‘the actor with greater capabilities socialises the actor with lesser capabilities into a normative order that favours the continuity of the former's status and position’Footnote 7 and hence ‘Great powers are responsible for socialising all other types of states in the system’.Footnote 8 Beyond neorealism, research on hegemonic international orders has also theorised socialisation and norm diffusion as a ‘transmission belt’ that privileges conformity to macro-level norms (such as diplomacy or sovereignty) and simultaneously reinforces hierarchical power relations in world politics.Footnote 9

The rise of constructivist IR has shifted the focus of socialisation research from material capabilities to ideational influences,Footnote 10 but the underlying assumption of hierarchical power relations remained unchanged.Footnote 11 Key works on constructivist socialisation research explicitly or implicitly invoke the analogy of teacher–student or master–novice relationships, arguing that ‘the socialisation of states is most likely to take place where opposition to change is weak and the socialised state sees itself as a student in a teacher-student relationship’.Footnote 12 Here the ‘desire to belong to a positively valued in-group’Footnote 13 plays a crucial role in this process of socialisation.

Yet the pedagogical model of socialisation based on hierarchical power relations is mainly derived from a specific Western experience: the socialisation of Eastern European states into mainstream Western norms after 1989. What brought research on socialisation to the forefront was the study of Eastern European socialisation or ‘Europeanisation’.Footnote 14 This case was, however, spatially and temporarily contingent on several conditions. First, many former communist states proclaiming the ‘return to Europe’ willingly took up the position of ‘students’ vis-à-vis Western ‘teachers’, who were regarded as positive role models.Footnote 15 Second, the collapse of the Soviet Union promoted the rise of the unipolar international order, in which hierarchical power relations between the West and the Rest became quickly entrenched in every international domain. Yet, a constructivist theory of socialisation built upon these anomalous conditions entails limited generalisability, since such ‘student-teacher relations … are seldom seen in international relations’.Footnote 16

This conceptualisation of a ‘teacher–student relationship’ corresponds to what is often described as the ‘authoritarian classroom’, where students are taught to obey the norms presented by teachers but are not given any opportunity to think critically.Footnote 17 Such a model of one-way socialisation has been used to study the dynamics of religious groups, where newcomers come to naturalise norms, values, and principles preached by religious leaders,Footnote 18 or workplace socialisation, through which workers come to adopt uniform standards of behaviour. In these cases, socialisation is conceptualised as a homogenising process through which individual actors come to be domesticated, ultimately losing their ability to think critically about the power/social relations within which they are embedded.

Whether neorealist or social constructivist, existing models of international socialisation are problematic since they take the primacy of hierarchical power relations for granted. These models are likely to be less useful in explaining the dynamics of norm diffusion in a world where the West no longer retains its preeminent position. More importantly, hierarchical models of socialisation follow a tradition of sociological inquiry that neglects the enabling aspects of the socialisation process. In the words of Kai Alderson,Footnote 19

International Relations scholars tend to draw on outdated notions of socialization. Sociology, especially Parsonian sociology, has in the past tended to emphasise social reproduction, conformity, the inculcation of common values, and the social restraint of individual impulses as defining features of socialization. But more recent work has criticised this tradition as leading to an ‘oversocialised’ model of human agency. Today, attention is paid to how socialization enables agents to articulate aspirations, to work together, and to become self-directed actors.

Already in the 1980s, many sociologists rejected the conceptualisation of socialisation as membership acquisition, and instead redefined socialisation as a life-long process of continuous learning through which an individual actor is exposed to multiple sources of influence.Footnote 20 As such, socialisation does not necessarily reinforce hierarchical power relations between the superordinate and the subordinate, but can also empower the powerless to seek greater agency and more equal power relations through self-directed learning.

In light of this, this article develops an alternative conception of ‘competitive socialisation’, broadly defined as self-directed learning and the internalisation of dominant norms by subaltern actors undertaken with an aim to challenge hierarchical power relations in international affairs.Footnote 21 Throughout much of international history, the West has not been a ‘positive’ reference group for the vast majority of humanity, who lived in a delicate mixture of fear and admiration of ‘superior’ Western powers. For instance, modernisation and Westernisation movements in China's last Qing dynasty drew upon the strategy of shiyi changji yi zhiyi (师夷长技以制夷), which essentially means ‘learning merits from the foreign to conquer the foreign’.Footnote 22 For many non-Western states, competition with the West (and/or with each other) played a potent role in the learning and adoption of the fundamental (Western) norms underpinning the Westphalian state system, such as sovereign equality, territorial integrity, diplomacy, and international legal norms.Footnote 23 Distinct from tactical behavioural modifications, actors engaged in competitive socialisation instituted wholesale domestic reforms, identity reconstruction, deep internalisation of dominant norms, and a closer integration with mainstream (Western) international society as a means to achieve more equal power relations. Through competitive socialisation activities, subaltern actors seek ‘positive self-esteem’ not in the demonstration of conformity or membership admission, but instead in the achievement of higher status through potentially out-performing the dominant norm leaders. Such recognition may come from a variety of sources, including fellow competitors, international audiences (other states and organisations), or domestic audiences. Hence positive self-esteem and a sense of self-realisation can be generated through more diffuse processes of social recognition even in the absence of membership admission.Footnote 24

The logic of competitive socialisation appears to underline a common global experience of many non-Western nations across time and space, and played an important role in the transformation of non-Western nations including China, Russia, and Turkey. Imperial Japan represents a notable case of competitive socialisation. After the 1868 Meiji Restoration, Japan's imperial elites eagerly learned Western political, economic, cultural, and civilisational norms, with many seeking education in Western universities. These socialisation efforts taken by Japan's imperial elites were, however, primarily driven by competitive motives.Footnote 25 Indeed, many Japanese nationalists of the era were eager to learn the norms of Western international society, believing that learning Western norms was the only way to defend Japan from Western predation and to protect its venerable traditions. Yukich Fukuzawa, the father of Japan's Westernisation, proclaimed in 1885 that ‘Western civilisation is like a plague’ and hence ‘the prudent policy is to immerse our nation so deeply into this plague so as to ensure that our people are accustomed to it’.Footnote 26

Though many of Japan's imperial elites assumed the role of ‘students’ learning Western norms (at Western universities and military academies), there was no sense of ‘we-ness’, and socialisation efforts were pursued as a means to enable Japan to challenge Eurocentric power hierarchy. At the same time, however, Imperial Japan's learning of Western norms resulted in ‘deep’ socialisation entailing radical identity change and domestic institutional reconfigurations. The outcome cannot be explained by the mainstream constructivist account emphasising the role of ‘we-feeling’ in inducing deep transformations.

From a macro-historical perspective, certain commonalities exist between the experiences of Imperial Japan and Imperial Russia, which had also undergone a series of radical Westernisation reforms since the seventeenth century.Footnote 27 By seeking closer integration with Western international society, Imperial Russia enhanced its competitiveness, raised its international standing, and subsequently challenged the Eurocentric world order. In this process, the deep internalisation of French (the diplomatic lingua franca of the time) played a crucial role in enabling Russia to compete with other great powers. Imperial Russia's socialisation into Western European diplomatic norms was so deep that French eventually became a semi-official language among Russian elites.Footnote 28 While many imperial elites genuinely felt attracted to French (and Western European) norms, Imperial Russia's Westernisation reforms were often driven by competitive motives, rather than a desire to ‘follow’ Western leadership. Widespread French fluency among Russian elites enabled Imperial Russia to participate more actively in European diplomatic conferences and more forcefully assert Russia's national interest at critical historical junctures.Footnote 29 Indeed, largely owing to the internalisation of Western norms, Imperial Russia rapidly strengthened its national capabilities, prevailed in the 1814 Battle of Paris, and even temporarily occupied Paris. These examples indicate that competitive socialisation has been an important means for major non-Western powers to challenge the existing power hierarchy in world politics. In light of this, the conventional theorising of ‘norm-taking’ as an act of submission and conformism requires reconceptualisation.

Situating competitive socialisation: A new framework

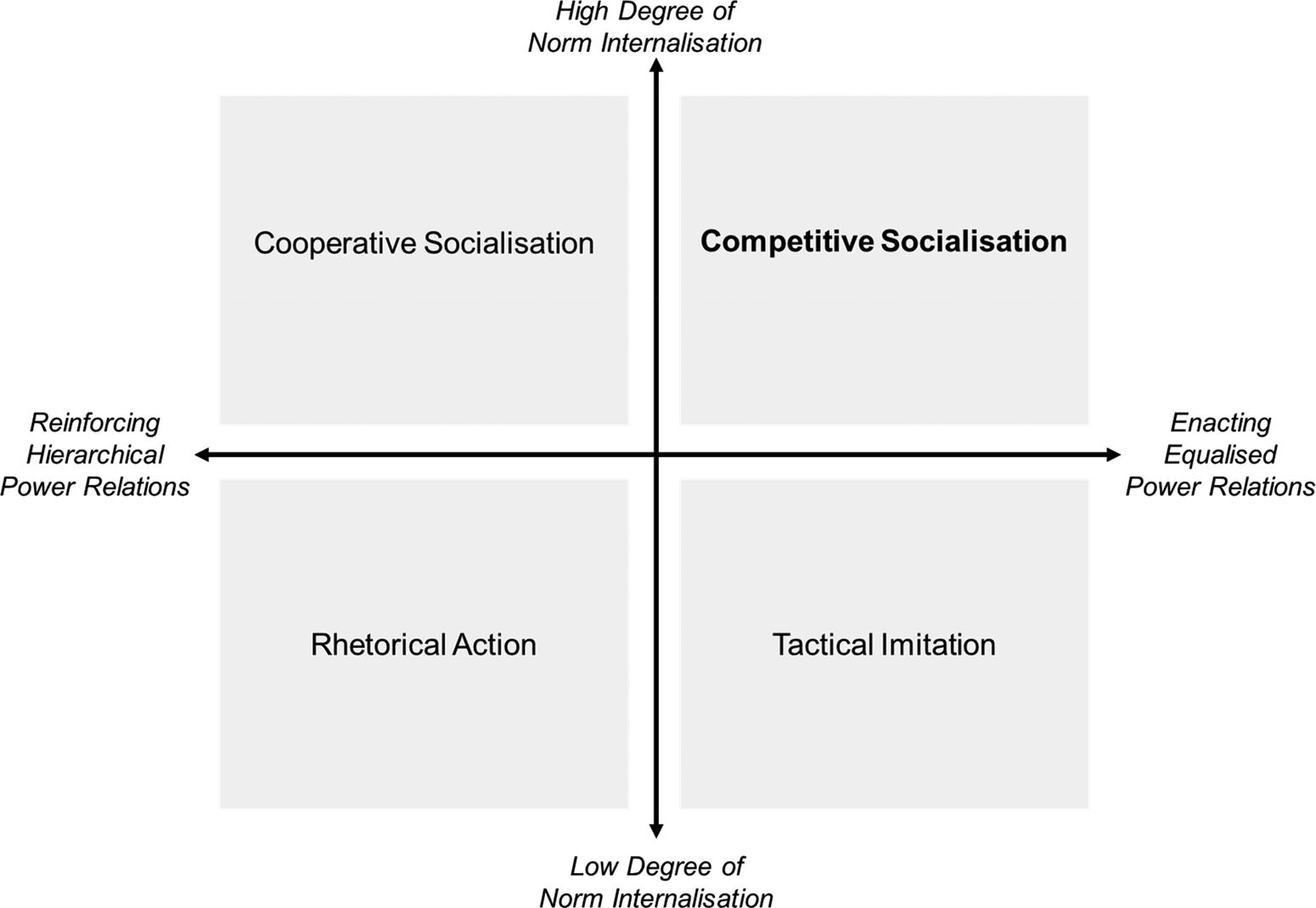

Building on these macro-historical reflections, this section develops an alternative typology of norm diffusion with different drivers and pathways, within which the practice of competitive socialisation is situated. Our typology departs from the conceptualisation of international (state) socialisation as ‘the process by which states internalise norms arising elsewhere in the international system’.Footnote 30 We concur with existing research that the internalisation of dominant norms through socialisation needs to be distinguished from superficial behavioural modifications such as ‘rhetorical action’Footnote 31 and tactical imitation, which usually do not result in changes in preferences and identities.Footnote 32 Departing from existing studies, however, we emphasise that the diffusion of dominant norms does not necessarily reinforce extant hierarchical power relations, as subaltern actors may also internalise dominant norms to enact more equalised power relations. Figure 1 below conceptualises four ideal-typical pathways of international norm diffusion differentiated along two axes: (1) the nature of power relationship enacted by norm diffusion process (hierarchical | equalised); and (2) the degree of norm internalisation (high | low).

Figure 1. Typology of norm diffusion mechanisms.

Our typology is a portfolio that encompasses ideal-types of different practices that can be mixed by international actors, rather than mutually exclusive choices and categories. Actual practices of norm diffusion are likely to be a combination of these different practices, since states are corporate actors encompassing different domestic groups with often contradicting preferences.

Theoretically, our typology helps clarify that the notion of socialisation commonly used in the Europeanisation research is a specific form of cooperative socialisation that reinforces existing hierarchical power relations, where subordinate actors actively seek to learn from their superordinate ‘teachers’ based on ‘we-feeling’, positive admiration, and the logic of appropriateness. In the cooperative socialisation process, novices find positive self-esteem in ‘we-feeling’, followership, collective conformity, and deference to the existing power relations, even though the process can involve certain reciprocal dynamics (for example, resistance or ‘localisation’).Footnote 33 Mechanisms of cooperative socialisation include normative persuasion, soft power, and the exercise of hegemonic power through which subaltern actors come to see dominant norms as ‘legitimate’ standards of conduct in international affairs.Footnote 34 As discussed above, however, the phenomenon of cooperative socialisation seems to be fully applicable only to a few cases – most notably, post-communist Eastern Europe in the 1990s and 2000s – and even here the fundamental identity change through socialisation has remained limited or short-lived.Footnote 35

The alternative concept of competitive socialisation enables researchers to broaden the scope of socialisation research and look for other pathways of norm diffusion and internalisation. Though socialisation is certainly about community-building,Footnote 36 this ‘community’ is not always characterised by a hierarchical teacher-student relationship, and can encompass wider variants including a competitive society. Competitive socialisation occurs when an actor embedded in competitive social relations seeks to emulate norms and practices performed by more successful rivals. While the process of socialisation can be driven by factors beyond cost-benefit calculus, we nonetheless emphasise that the sense of ‘positive self-esteem’ does not necessarily come from conformity and ‘we-feeling’. Subaltern actors can also seek ‘positive self-esteem’ by challenging hierarchical power relations, competing for higher status, and reclaiming their agency. That said, competitive socialisation remains a social practice of accepting/internalising existing norms, and is not about revising or overthrowing the existing normative structure (such revisionist practices would require a different theoretical framework). Successful competitive socialisation still results in the affirmation of existing norms. Unlike cooperative socialisation (in which followership is positively conceived), however, competitive socialisation equalises existing power relations by eroding the monopoly of social status retained by dominant actors. In an extreme case, subaltern actors engaged in the practice of competitive socialisation may even outperform dominant powers and threaten their preeminent social status.

In this context, the internalisation of dominant norms can be a strategy to challenge the leadership of more successful actors, protect oneself from predatory ambitions (real and/or perceived) of superior actors, or challenge Western dominance of particular institutions or practices.Footnote 37 Imperial Russia challenged European primacy by deeply internalising European norms and by becoming a great power, while Imperial Japan challenged the Eurocentric imperial order by deeply internalising Western norms and being recognised as a great power. Unlike other forms of shallow learning, competitive socialisation is holistic and can induce fundamental changes in preferences and identities.

As an endogenously driven process, self-directed learning efforts play a crucial role as a mechanism of competitive socialisation. We theorise that competitive socialisation takes place chiefly through the mechanism of what can be called ‘participant observation’. Actors who seek to internalise norms and practices performed by dominant competitors (primarily national elites and policymakers in subaltern states) can immerse themselves deeply into social networks and communities of practice developed and maintained by superior rivals.Footnote 38 In so doing, the emulating actors observe and learn best practices performed by more successful competitors, but without being engaged in a kind of deferential teacher-student hierarchy. This enables the emulating actors to maintain independent agency. In an open international society where exchanges of information are frequent and intensive, self-directed learning can take place through extensive and sustained participation in multilateral forums, such as the UN Security Council or the World Trade Organisation, or through participation in multilateral practices such as trade negotiations or peace operations.Footnote 39

Having established the difference between cooperative and competitive socialisation practices, it is imperative to situate the concept of competitive socialisation vis-à-vis similar diffusion processes. To begin, rationalist IR scholars have shown that norm acceptance can be induced by the manipulation of material incentives such as positive/negative sanctions (‘carrots and sticks’). Materially induced norm compliance, however, usually results in shallow learning and superficial behavioural modification characterised by rhetorical action, where ‘only action and rhetoric are changed in order to appear to comply with the demands of the socializing agent’.Footnote 40 Rhetorical action is a phenomenon structured by hierarchical power relations, where ‘norm leaders’ manipulate the cost-benefit calculus of ‘norm takers’ to induce their reluctant compliance through conditionality, organisational membership, and other disciplining practices. This works through ‘social influence’, defined as ‘a class of processes that elicit pro-norm behaviour through the distribution of social rewards and punishments’.Footnote 41

As such, we conceive of rhetorical action and other forms of ‘behavioural compliance’ as a practice of ‘window-dressing’ that reinforces existing power hierarchies, but does not reconfigure unit-level preferences and identities.Footnote 42 Concrete examples of rhetorical action could include developing countries superficially adopting liberal democratic norms to satisfy Western aid donors. In this sense rhetorical action is the opposite of competitive socialisation, which is characterised by the holistic internalisation of dominant norms aimed at transforming and equalising – and not reinforcing – existing power hierarchies. It is, of course, not always easy to distinguish the two empirically.

In contrast to the passive and defensive practice of rhetorical action, there are active and self-directed practices of imitation, copying, mimicking, emulation, cognitive role-playing, and other forms of offensive strategic learning aimed at mocking, subverting, and/or challenging the existing power relations.Footnote 43 In our typology, we regroup these practices as tactical imitation.Footnote 44 Concrete examples include Russia appropriating the R2P norm to justify its intervention in Ukraine (see below) and China appropriating human rights norms to criticise the United States (for instance, China's publication of annual reports on the human rights situation in the United States). Tactical imitation may enable subaltern actors to challenge existing power relations, but it is unlikely to have a lasting and transformative impact on the overall normative structure, because it tends to be a sporadic practice aimed at gaining temporary tactical advantages.

Competitive socialisation is distinct from tactical imitation in several respects. First, tactical imitation is an asocial practice that usually does not involve any aspect of community engagement. Jack Levy and Benjamin Goldsmith, for example, developed the concept of ‘foreign policy learning’ and ‘observational learning’, respectively, where states learn from foreign policy successes and failures of others.Footnote 45 This may enhance one's competitive edge, but does not involve any substantial social activities, which are essential in seeking more equalised power relations. In the above-discussed cases, Imperial Russia and Japan both internalised dominant Western norms and immersed themselves deeply into the Western international society, which enabled them to challenge existing power hierarchy from within.

More importantly, tactical imitation may result in an ad-hoc (mis)appropriation of dominant norms by subaltern actors, but it does not result in the internalisation of these norms, and hence, no fundamental changes in preferences and identities are observed. Take, for example, Russia's use of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) norm. In the wake of the 2014 Ukrainian crisis, Russia justified its intervention in Crimea by invoking the R2P norm, where the Russian government supposedly fulfilled its solemn ‘responsibility to protect’ endangered Russian citizens and ‘oppressed’ Russophone minorities residing in Crimea. While this act of ‘parodying’Footnote 46 allowed Russia to sow confusion in the West and to gain a tactical advantage, it was clearly an ad-hoc co-optation of a dominant norm with no discernible changes in preferences and identities. This is evident from the fact that Russia continues to oppose the norm in Syria and elsewhere after 2014.Footnote 47 Though tactical imitation may constitute a sporadic action aimed at challenging existing power hierarchy, observers can differentiate it from the practice of competitive socialisation by interrogating carefully the degree of norm internalisation.

From a broader sociological viewpoint, our theoretical framework is also compatible with the research on social status in world politics, informed by social identity theory (SIT).Footnote 48 Status refers to ‘collective beliefs about a given state's ranking on valued attributes’.Footnote 49 The central explanatory factor in the SIT framework is ‘social mobility’, defined as the permeability of superordinate ‘clubs’ by subordinate actors. When social mobility is high, subordinate actors can seek to join the club (for example, membership admission) and gain a higher status.Footnote 50 When social mobility is low, however, subordinate actors remain dissatisfied with their ‘inferior’ status. The resulting cognitive dissonance leads them to adopt strategies of ‘social creativity’ and/or ‘social competition’.Footnote 51 For example, Steven Ward shows that the widespread perception of social immobility enabled anti-Western nationalists to hijack the domestic political arena in Imperial Japan, leading to its radical revisionist behaviours in the 1930s.Footnote 52

As Ann Towns shows, norms are fundamentally about hierarchy, ranking, and social stratification, and hence norm-related behaviours (including the four ideal-typical practices identified above) can (re)shape a state's international status.Footnote 53 Our argument is, however, distinctive from the existing research on social status in two ways. First, while SIT clearly distinguishes emulation (mobility) from competition, we show that these are not necessarily mutually exclusive practices. In fact, subaltern actors may adopt competitive behaviours even in the policy domains marked by a relatively high degree of social mobility (such as peacekeeping and multilateral development assistance, see below for more details). In this light, our concept of competitive socialisation may be conceived as a mixture of mobility and competition. Second, while SIT generally assumes a fixed set of state preferences and identities, our case studies show that competitive socialisation can result in their transformation. In this light, our framework can potentially serve as a point of convergence to bring together status and socialisation research in world politics, even though more detailed exploration of this topic goes beyond the scope of this article.Footnote 54

Operationalising competitive socialisation in practice

In order to systematically investigate the phenomenon of competitive socialisation, researchers need to be able to specify the nature of power relations enacted by norm diffusion processes and the degree of norm internalisation. We address each of these methodological aspects in turn.

By paying closer attention to the social aspects of norm diffusion, researchers can distinguish the enactment of equalised relations from the reinforcement of hierarchical relations. The reinforcement of hierarchical relations is observed when the diffusion of dominant norms constructs and entrenches an explicit teacher–student relationship, where a superordinate actor monitors and enforces norm compliance by a subordinate actor. The power hierarchy is naturalised through the followership of the subordinate actor, who finds positive self-esteem in ‘we-feeling’, collective conformity, and deference to the existing power relations. As discussed above, the notable case of such hierarchical relationship is cooperative socialisation of post-communist Europe in the 1990s.

In contrast, competitive socialisation equalises power relations by deconstructing the supposed hierarchical relationship between the subaltern and the dominant. The diffusion of Western norms by and in itself does not necessarily mean the reinforcement of Western dominance, as subaltern actors have challenged the global power hierarchy by internalising Western norms. The practice of competitive socialisation may be particularly empowering for rising powers who can improve their relative position and status vis-à-vis a hegemonic power by internalising dominant norms. More concretely, researchers can observe the enactment of equalised power relations by systematically inquiring how the internalisation of dominant norm is framed by political elites in subaltern states. Usually, states engaged in the practice of competitive socialisation frame the internalisation of dominant norms as a means to strengthen their independent agency. The advancement of such discursive framing can be traced by scrutinising policy documents, official discourses, and other public data.

Next, operationalisation of the degree of internalisation builds on recent advancement in norm research. Jonas Tallberg et al. differentiate the degree of norm internalisation by distinguishing three levels: (1) norm absence or rejection; (2) ‘norm recognition’ defined as rhetorical reference to a norm (‘talking the talk’); and (3) ‘norm commitment’ defined as the institutionalisation and codification of a norm accompanied by policy programmes dedicated to its implementation (‘walking the walk’).Footnote 55 In our own conceptualisation, the low degree of norm internalisation is largely consistent with the notion of norm recognition. In contrast, the high degree of norm internalisation emphasises the observance of domestic institutional reconfigurations, such as the establishment of new domestic institutions prompted by the internalisation of foreign norm. Since states are corporate actors embracing different groups and individuals, institutionalisation is the key to sustainable norm internalisation.Footnote 56

For the purpose of socialisation research, however, we also add two supplementary qualifications. First, the deep effects of socialisation can be most clearly observed when norm internalisation coincides with the acquisition of a previously denied state identity or the rearticulation of preferences. Second, the deep effects of socialisation can be also observed when the internalising state demonstrates leadership aspirations, that is, when it does not only internalise the dominant norm, but also actively seeks to assume a leading role promoting the dominant norm by establishing new global institutions, partnerships, and other initiatives. In light of these supplementary additions, Table 1 below summarises our differentiation of high and low degrees of norm internalisation, as well as its absence.

Table 1. General guidelines for the differentiation of norm internalisation.

With the rubric articulated above, the rest of this article examines how China's approach to the peacekeeping norm and Russia's approach to the multilateral development assistance norm changed over time, from initial norm rejection, to a passive acceptance, and finally to active learning and internalisation through appropriate practices. We employ a broader understanding of ‘subaltern’ actors to denote actors who are not part of the dominant core of the liberal international order. Though China and Russia – major military powers and permanent members of the UNSC – are materially more capable than classical subaltern states (in the postcolonial sense), they are also normatively marginalised actors seeking to thrive under the liberal order.Footnote 57 In this sense, China and Russia constitute ‘most likely’ cases of relatively more resourceful powers that are capable of engaging in the practice of competitive socialisation (and other practices articulated in the typology). The case studies emulate the research design of other socialisation research by tracing the evolution of discourses and practices of socialising actors over time, based on qualitative research, including the analysis of key policy texts and approximately fifty interviews conducted in Beijing and Moscow, as well as in New York and Geneva.Footnote 58 Interviewees were government officials and peace/development experts in China and Russia, as well as UN professionals and Western representatives with intimate knowledge of Chinese and Russian policy in the field of peace and development. Policy texts and interview data were also systematically analysed along with the indicators articulated in Table 1 above.Footnote 59

Competitive socialisation in practice

China's competitive socialisation in peace operations

International peacekeeping constitutes an integral part of the postwar liberal order centred on the UN multilateral security system.Footnote 60 State actors socialised into the norms of peacekeeping operations (PKO) come to regard it as a legitimate practice of international security governance and seek to demonstrate their norm commitment by providing financial and/or troop contributions to support peace operations.Footnote 61 To date, Western powers at the UNSC, and in particular the US, the UK, and France, have played a disproportionately influential role in the articulation and diffusion of the PKO norm. In the past, PKO missions were primarily funded by major Western powers. In 2021, more than half the PKO budget is still funded by six NATO members (US 27.89 per cent, Germany 6.09 per cent, UK 5.79 per cent, France 5.61 per cent, Italy 3.3 per cent, and Canada 2.73 per cent).Footnote 62 Beyond the Western dominance of PKO finance, a large number of UN officials and other multilateral security experts who shape the PKO norm are from Western countries or are educated in Western institutions, whereas contributions from non-Western states remain limited.Footnote 63

Though Beijing has advanced an alternative norm of the ‘developmental peace’ in the policy domain of development and peacebuilding, there is no distinctively Chinese approach to peacekeeping. As scholars noted, China has been largely a norm taker when it comes to the PKO norm.Footnote 64 Yet, China's stance on the PKO norm has moved far from blunt rejection before the 1990s, to tactical modifications in the 1990s, and finally to deep internalisation after the 2000s. As Miwa Hirono, Yang Jiang, and Marc Lanteigne maintain, ‘in the space of less than twenty years, Chinese policy towards UNPKO was transformed from wariness and avoidance to acceptance and enthusiasm’.Footnote 65 In line with the typology developed above, we argue that China's conduct of ‘norm-taking’ and internalisation of the PKO norm represents a practice of competitive socialisation directed at enhancing its own agency and challenging the existing global power hierarchy. In this subsection, we trace the evolution of China's stance on the PKO norm over three phases (I: before 1987; II: 1988–2000; and III: after 2001) and show how competitive socialisation helps us better understand China's reconfiguration of its preference and identity with regard to the norm.

Phase I: Rejection of the PKO norm (–1987)

Until the early 1980s, China categorically rejected the PKO norm and sought to delegitimise peacekeeping operations as a tool of hegemonic intervention. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Communist Party actively disseminated propaganda materials framing PKO as a subversive attempt by imperial powers. In 1965, for example, the state-owned People's Daily vehemently criticised the United Nations operation in the Congo (ONUC) as ‘open[ing] the door for neo-colonialist interference in Congo’.Footnote 66 While Communist China assumed its permanent seat at the UNSC in 1971, its scepticism against the PKO norm persisted in the subsequent decade: China refused to pay any peacekeeping-related expenses until 1981 and refused to participate in any PKO missions until the early 1990s.

Many Western policymakers at the time considered China's categorical rejection of the PKO norm as a challenge to the postwar liberal international order. For example, Brigadier Michael Harbottle, chief of staff of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus from 1966 to 1968, deplored that China ‘sees itself as the champion of the Third World, unequivocally opposes UN peacekeeping operations of any kind on the principle that they are an interference in conflicts which are the concern of the state or states involved and of no one else’.Footnote 67 The rejection of the PKO norm served China's core strategic interest at the time, by which China positioned itself as a defender of the Third World from hegemonic imperialists. The rejection was also consistent with China's state identity as a champion of sovereignty and non-intervention norms in world politics. By delegitimising the PKO norm, China sought to build a coalition of anti-hegemonic states that would foster its domestic and international legitimacy. Here it is important to note that disruptive events such as communist China's assumption of its UNSC permanent seat (1971) or Deng Xiaoping's initiation of ‘opening-up’ domestic reforms (1979–) did not result in any meaningful change in Beijing's stance on the PKO norm.

Phase II: Rhetorical action and tactical imitation (1988–2000)

After the late 1980s, China gradually came to recalibrate its approach to the PKO norm guided by a new doctrine of UN-centric multilateral diplomacy.Footnote 68 As President Jiang Zemin elaborated, a mainstay of this new foreign policy lay in ‘playing a role in the UN, other international organisations and regional institutions, and supporting developing countries to safeguard their legitimate interests in the existing international system’.Footnote 69 Driven by this vision, China joined the UN Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations in 1988. In 1992, Beijing sent a peacekeeping engineering unit composed of four hundred officers and soldiers to the UN Provisional Authority in Cambodia, which marked its first participation in UNPKO. In 1997, China also agreed in principle to participate in the UN Standby Arrangements System.

Existing research has shown that the change in China's approach to the PKO norm was driven by several factors. Beijing faced mounting social pressure to reformulate its stance on PKO after its 1971 reclamation of the UNSC seat. As a permanent member of the UNSC, China needed to demonstrate its commitment to upholding international peace and security.Footnote 70 Through repeated interactions with UNPKO officials, Chinese policymakers also gradually developed a positive understanding of PKOs and no longer viewed them as a veil for imperialist intervention. Despite this, China's internalisation of the PKO norm remained shallow in the 1990s. Until the 2000s, Chinese peacekeepers mostly carried out support tasks such as logistics, engineering, road construction, and medical care while refraining from being involved in fulfilling core peacekeeping tasks such as security provision. Though Beijing no longer engaged in the dissemination of anti-PKO propaganda, Chinese policymakers remained concerned that active support for the PKO norm might enable Western powers to intervene into domestic affairs of developing countries. In light of this, China's initial shift in its stance on the PKO norm can be seen as an instance of rhetorical action, where Chinese policymakers engaged in a series of behavioural modifications to bolster credibility as a constructive UNSC member.Footnote 71 At the same time, by engaging in the tactical imitation of PKO tasks, Chinese officers also gained valuable experience in international security cooperation and enhanced China's power projection capability. In sum, China's initial shift in its stance on the PKO norm in the 1990s resulted in certain behavioural modifications, but without any fundamental reconstitution of its preferences and identities.

Phase III: Competitive socialisation (2001–)

In contrast to the superficial behavioural modifications of the 1990s, China embarked on deeper internalisation of the PKO norm since the early 2000s and has even emerged as a leading advocate of peacekeeping in the global arena. In 2004, Ambassador Wang Guangya stated at the UNSC that ‘Peacekeeping operations are a highlight of the United Nations and the priority of the work of the Security Council. Further strengthening peacekeeping operations will help enhance the authority of the Security Council, bolster collective security, expand the role and influence of the United Nations and promote multilateralism’.Footnote 72 Other top Chinese officials have repeatedly made similar declarations.Footnote 73

The deeper internalisation of the PKO norm prompted domestic institutional reconfigurations. In 2001, the Ministry of National Defence established the Peacekeeping Affairs Office (PKAO), while peacekeeping activities are also incorporated into the People's Liberation Army (PLA)'s real-combat drills. Participation in PKOs is stressed as a major responsibility and achievement of the PLA in the White Paper on National Defence since 2004. Peacekeeping police and military training centres were subsequently established near Beijing, which regularly tutor peacekeepers from fragile countries based on UN pre-deployment training materials. In December 2009, China held an unprecedented conference on international peacekeeping in Beijing, inviting government officials and military officers from 22 countries as well as representatives of the UN, AU, EU, and ASEAN to discuss PKO reforms. In June 2015, China also jointly held a training session with the UN Women on the theme of civilian protection in PKOs. Diligent compliance with the PKO norm by China is well documented, as UN, AU, and Western officials who served in PKO missions almost unanimously praise Chinese peacekeepers as among ‘the most professional, well-trained, effective and disciplined in UN peacekeeping operations' and ‘Chinese personnel are increasingly involved in mission leadership and decision making’.Footnote 74 The reception of the UN Medal for Service by the Chinese Peacekeeping Battalion in 2017, 2019, and 2020 featured prominently in China's state media.Footnote 75 In 2020, a documentary film about China's first peacekeeping infantry battalion in South Sudan was released, accompanying the publication of the White Paper on China's Thirty Years’ Participation in the UN Peacekeeping Operations by the State Council.

In recent years, China also emerged as a major contributor to the peacekeeping budget and troops. As of January 2021, China contributes approximately 2,500 peacekeepers to various PKO missions, more than those of other P5 members such as France (623), UK (529), Russia (62), and US (30).Footnote 76 While Chinese peacekeepers used to carry out only support tasks until the early 2000s, they now also occasionally assume military roles as China began to contribute combat forces, evidenced by its contribution of comprehensive security forces to Mali and of more than one thousand combat troops to South Sudan (UNMISS). To support the rapid deployment of UNPKOs, China also set up a three hundred-person standby peacekeeping police force in 2016, followed by the establishment of a military peacekeeping force composed of eight thousand personnel in 2017. China contributes 15.21 per cent of the entire UNPKO budget in 2020–1 and ranked second after the US in terms of financial contribution.Footnote 77 In 2016, Beijing also launched the UN Peace and Development Trust Fund (UNPDF) with a $200 million contribution, with one of its major goals being peacekeeping capacity-building for developing countries.

Using the typology developed in the previous section, we argue that the radical change in China's stance on the PKO norm constitutes a case of competitive socialisation. Throughout our interviews with Chinese officials and experts, the consensus was that the pursuit of international status and influence vis-à-vis Western powers constitutes the main driving force behind China's shifted stance on the PKO norm. For instance, an interviewee from the China Foreign Affairs University – China's main diplomatic school – explicitly stated that participation in UNPKOs represents an effective means to ‘exerting greater discursive power and influence of China on international peace and security’.Footnote 78 He Yin, an Associate Professor at the China Peacekeeping Police Training Centre and a former peacekeeping police officer, also emphasises that Beijing's peacekeeping leadership ‘not only serves its “peaceful rise” aspirations, but can also be used as clout to balance against [Western] unilateralism and yield valuable political currency for it to promote its multilateral agenda’.Footnote 79 Zhao Lei, the Deputy Dean of the International Strategic Research Institute of the Central Party School of the Communist Party of China, similarly observes that China seeks to counterbalance Western influence by proactively participating in agenda-setting for global peace operations.Footnote 80

Through the practice of competitive socialisation, China acquired a previously denied identity of international peacekeeper, reconstituted its foreign policy preferences, and emerged as a leader in global peace operations. The deep internalisation of the PKO norm empowered China to project its vision of peace as a representative of the developing world and counter the Western discourse of a ‘China threat’ and ‘irresponsible’ power. What is ironic is that previously, Western policymakers would deplore China's blunt rejection of the PKO norm as a challenge to the liberal order; today, Western observers find China's passionate promotion of the PKO norm equally troubling, since it also (and perhaps more effectively) challenges the Western primacy in multilateral security governance.Footnote 81

Russia's competitive socialisation in multilateral development assistance

Multilateral development assistance (MDA) forms the basis of the postwar liberal order and is a cornerstone of global efforts to promote the Sustainable Development Goals. The central purpose of the MDA norm is to increase transparency and impartiality in the aid provision process through multilateral institutional delegation and to maximise development impacts. Since 1945, Western powers such as the US, the UK, and Western-dominated global development agencies such as the World Bank and UNDP have traditionally assumed a leading role in the articulation and diffusion of the MDA norm.Footnote 82 The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has also played an important role in promoting and coordinating best practices in international development assistance in general. Those states that are socialised into the MDA norm regard multilateral foreign aid as a legitimate practice of international development governance, and seek to demonstrate their commitment to the norm by following best practices on such things as aid reporting, national ownership, programme monitoring and evaluation, and harmonisation of aid practices.Footnote 83

As Denis Degtiariov and Yury K. Zaytsev note, Russia has been largely a norm-taker when it comes to the MDA norm.Footnote 84 Yet Russia's stance on the MDA norm has undergone a radical shift from norm demotion until the early 2000s, to tactical modifications in the mid- and late-2000s, and finally to deep internalisation after the 2010s. In line with the typology developed above, we argue that Russia's shift from ‘norm-taking’ to internalisation of the MDA norm is a practice of competitive socialisation directed at challenging the Western monopoly in the development community. In this section, we trace the evolution of Russia's stance on the MDA norm over three phases (I: before 2003; II: 2004–09; and III: after 2010) and demonstrate how the concept of competitive socialisation helps us understand Russia's reconfiguration of its preferences and identity with regard to the norm.

Phase I: Rejection and marginalisation (–2003)

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union criticised the notion of international development as an instrument of capitalist world domination and advanced an alternative approach of mutual assistance to fraternal states.Footnote 85 Soviet officials habitually demonised the OECD as a club of imperialists and developed the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) as its counterweight.Footnote 86 Though the polemical rhetoric was dropped after 1989, Russia continued to marginalise the MDA norm in the 1990s and preferred to channel its foreign assistance through bilateral mechanisms.

One might argue that Russia was significantly weakened in the 1990s and did not have the resources to engage in development assistance as a donor. This is partially true as Russia drastically reduced its foreign aid programmes after 1991, and though Boris Yeltsin's government proposed the creation of a Russian Agency for International Cooperation and Development, the plan did not materialise due to domestic turmoil.Footnote 87 However, the 1990s was not a period of total disengagement from foreign assistance, and Yeltsin's Russia pursued an adventurist foreign policy in the post-Soviet space and intervened in multiple neighbouring states such as Moldova (Transnistria), Georgia (Abkhazia and South Ossetia), Armenia/Azerbaijan (Nagorno Karabakh), and the Tajik civil war.Footnote 88 In Tajikistan, for instance, Moscow sent as many as 25,000 troops to support the embattled Tajik government, where the Russia-led peace operations performed various security provision and reconstruction tasks.Footnote 89

Moscow continued its foreign assistance activities in the 1990s, but Russian policymakers preferred to manage them through bilateral mechanisms and expressed little interest in coordinating with the larger development community. The prioritisation of bilateral assistance served national interests, as it enabled Moscow to capitalise on its informal contacts with post-Soviet elites, as noted by a former senior Russian official who worked on various development projects.Footnote 90 Though Russia in the 1990s no longer sought to delegitimise multilateral development institutions, the MDA norm remained persistently marginalised and failed to gain traction in Russian domestic politics.

Phase II: Rhetorical action and tactical imitation (2004–09)

Since the early 2000s, however, Russia gradually altered its approach to the MDA norm, moving towards at least a shallow engagement.Footnote 91 In 2004, the Russian government and UNDP jointly launched a new partnership entitled ‘Russia as Emerging Donor’ and Russian officials actively participated in UNDP's ‘Emerging Donors Initiative’ between 2006 and 2010. Following Russia's G8 chairmanship in 2006, Moscow released the Concept on Russia's Participation in International Development Assistance (Kontseptsiya uchastiya v sisteme mezhdunarodnomu razvitiyu, or IDAC) in 2007.Footnote 92 The 2007 IDAC demonstrated Russia's apparent openness to the MDA norm, as it explicitly endorsed key MDA documents such as the 2005 OECD Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. It was also uncharacteristically self-critical. The Concept noted that ‘Until recently, Russia's participation in development assistance was quite limited both in scope and types of assistance’,Footnote 93 and even deplored that ‘Russia is the only country in the Group of Eight whose laws and government regulations do not even include the concept of official development assistance (ODA)’.Footnote 94 Following the launch of the 2007 IDAP, Russia initiated learning opportunities that represented an opening to internalisation of the MDA norm. In 2008, for instance, the Russian Finance Ministry held a joint international workshop with the World Bank entitled ‘Development Aid Statistics: International Experience and the Creation of a Russian Accounting and Reporting System’, sponsored by USAID, DFID, the OECD, and UNDP.Footnote 95 Russian officials also engaged in learning exercises, as they ‘visited every donor state around the world to accumulate information on their development infrastructure’.Footnote 96

Russia's shifted stance on the MDA norm can first be understood as a form of rhetorical action, where Moscow engaged in behavioural modifications to demonstrate its conformity with the global development mainstream. The IDAC's strong self-criticism provides evidence to support such interpretation. At the same time, however, these behavioural modifications can be also seen as an act of tactical imitation, where Moscow sought to strengthen its international standing by internalising the Western norm. Indeed, notwithstanding its positive identification with the multilateral development community, the 2007 IDAP proclaimed that ‘Russia's status of a superpower suggest that Russia could pursue a more active policy in international development assistance’,Footnote 97 which will ‘strengthen the credibility of Russia and promote an unbiased attitude to the Russian Federation in the international community’.Footnote 98 Russia's closer integration into the development community was framed as a means to strengthen its competitiveness in global politics, but despite these aspirational claims, Russia's internalisation of the MDA norm in the 2000s remained superficial, as Russia's contribution to multilateral development agencies and programmes remained limited (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Russia's ODA (2004–17) (US $ millions).

Note: Data for 2004–09 is from Ministry of Finance (2012); data for 2010–17 is from Zaytsev, ‘Russia's approach to official development assistance and its contribution to the SDGs’.

Disaggregation was not available for 2004–09.

Phase III: Competitive socialisation

In contrast to the superficial behavioural modifications of the 2000s, Russia embarked on a deeper internalisation of the MDA norm since the beginning of the 2010s. Both the 2012 Russian Federation ODA National ReportFootnote 99 and the revised 2014 IDACFootnote 100 endorsed major MDA declarations (including those from OECD) and explicitly framed multilateral aid as a cornerstone of global governance. Most notably, Russia began to adopt OECD-DAC reporting standards for ODA provision even though it is not an OECD member. Along with this, the initial prioritisation in bilateral assistance mechanisms in Russian ODA waned, while the proportion of multilateral aid in the overall Russian aid portfolio increased considerably to 30–50 per cent.Footnote 101 Figure 2 illustrates the trends in Russian ODA.

Though a Russian international aid agency was not established largely due to political infighting, Russian policymakers advanced domestic institutional reforms and implemented the deeper internalisation of the MDA norm.Footnote 102 The revised 2014 IDAC called for the creation of a national Commission for International Development Assistance tasked to coordinate among different domestic constituencies, along with other plans for institutional streamlining.Footnote 103 More importantly, Russian policymakers embarked on efforts to institutionalise the culture of international development by cultivating domestic norm champions and expertise. A Russian Foreign Ministry advisor remarked that Russia generally lacks the culture of framing foreign assistance as ‘aid’ activities, and hence those who carry out assistance projects often fail to recognise their activities fall within the domain of international development.Footnote 104 In light of this, the Russian Foreign Ministry's Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO) – Russia's main diplomatic school – launched new courses and training seminars on international development cooperation. The World Bank's ‘Russia as Emerging Donor’ programme supported this domestic re-education attempt by initiating a collaborative pedagogical exercise involving various Russian ministry officials and scholars, which produced a volume entitled ‘International Development Assistance' in 2014.Footnote 105 The textbook has been used to educate future Russian elites at MGIMO, who are now trained with the four hundred-page reader on various themes of international development such as structures and practices of established donors and best practices of project monitoring and evaluation. In addition, UNDP also implemented a collaborative project that created an online database enlisting more than 250 Russian international development assistance experts, who now play a key role in the internalisation of the MDA norm as educators and government advisors.Footnote 106

On top of these domestic reforms, Russia has assumed a leadership position in launching various multilateral development initiatives since the early 2010s. In 2015, Russia and the UNDP signed a new Partnership Framework Agreement, followed by the Agreement for the Establishment of the Russia-UNDP Trust Fund for Development in June 2015, with an initial funding of $25 million.Footnote 107 UNDP in 2016 noted that ‘with Russian funding, UNDP has been able to launch innovative initiatives across the region, addressing the needs of the vulnerable, spurring employment, growth and more effective governance’.Footnote 108 The World Bank also supported the launch of the Russia Education Aid for Development (READ) Trust Fund since 2008, which has been recently upgraded to the READ2 Trust Fund.Footnote 109 Both UNDP and World Bank officials note significant progress with regard to Russia's deeper integration into global development cooperation regimes and the deep internalisation of the MDA norm.

As in China's case, Russia's deep internalisation of the MDA norm is difficult to explain in terms of conventional understandings of cooperative socialisation. Russia's internalisation of the MDA norm continued and accelerated even after the 2014 Ukrainian crisis, which resulted in a breakdown in Russian-Western relations, Russia's ejection from the G8, and the suspension of Russia's OECD accession process.Footnote 110 In the midst of the economic crisis triggered by Western sanctions, Russia's contribution to multilateral development assistance doubled from 2014 to 2017 (as shown in Figure 2). In light of this, we argue that the change in Russia's stance on the MDA norm is a case of competitive socialisation. In interviews, Russian officials and experts remarked that the pursuit of international status and influence vis-à-vis Western powers constitutes a major driving force behind Russia's shifted stance on the norm. For instance, an expert from the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration – who participated in various collaborative MDA projects with the World Bank and other agencies – argued that Russian policymakers are keen to learn the West's best MDA practices to enhance Russia's own standing, and that Moscow's adoption of the OECD standards should not be seen as a willingness to blindly follow Western leadership in the field.Footnote 111 World Bank officials also observed that Russia's internalisation of the MDA norm is mainly directed at self-enhancement.Footnote 112

Though Russia's learning of the development norm involved ‘teachers’ from the Western aid community, much of this process was driven by Moscow's self-directed learning efforts. Ultimately Russia envisions breaking the Western monopoly in the development field and establishing itself as an alternative development partner. Support for such interpretation can be found in policy documents. The 2014 IDAC clarifies that ‘Russia pursues an active and targeted policy in the field of international development assistance which serves the national interests of the country’ and aims to ‘strengthen the country's positions in the world community’.Footnote 113 This will ‘strengthen a positive image of the Russian Federation and its cultural and humanitarian influence in the world’. More bluntly, the 2014 IDAC proclaimed that Russia's closer integration into the multilateral development community would serve to strengthen ‘equality and democratisation of the system of international relations’,Footnote 114 where ‘democratisation’ in this context refers to the building of the multipolar world where Western primacy is constrained.Footnote 115

Though there remain deficiencies and capacity gaps, Russia acquired a previously denied identity as a multilateral donor while reconstituting its state preferences and national interest through competitive socialisation. In prior periods, the overt prioritisation of bilateral assistance was considered as national interest; since the last decade, however, the deep internalisation of the MDA norm came to constitute Russia's national interest as it empowers Russia to seek higher global status and enhance its credibility as a ‘responsible’ great power. What is particularly interesting in this case is that Russia framed itself as an emerging multilateral donor and enlisted the learning support from the World Bank, where Russia's voice and influence is minimal.Footnote 116 In this sense, the acceptance and internalisation of the Western-centric MDA norm has enabled Russia to enhance its own agency and seek to enact more equal power relations in global politics.

Conclusion

Existing literature tends to conflate processes of socialisation with the building of cooperative social relations. This leads to a neglect of the dynamics of competitive socialisation, and the way in which the adoption of dominant norms can also allow a state to challenge the established hierarchy in world politics. While the role of competitive factors in macro-level norm socialisation processes has been recognised by scholars working in a more structuralist tradition, it has been less well integrated into the study of endogenous and self-directed internalisation of norms, associated with regular and routine practices of multilateral policies such as peacekeeping or development assistance. The cases of the evolution of Chinese engagements with UN peacekeeping, and Russia's orientation towards development assistance, both demonstrate, however, that the logic of competitive socialisation better explains their changes in preferences and identities in the domains of PKO and MDA, respectively. The logic of competitive socialisation is also useful in clarifying the interplay between norm socialisation and power politics, and in some respects bridges the divide between rationalist and constructivist accounts of norms. In an increasingly multipolar global order, competitive socialisation processes may become more salient and ubiquitous, and certainly warrant greater scholarly attention.

In light of this, we point to two specific directions for further research. First, research is needed to explain why subaltern actors and rising powers choose to engage in competitive socialisation of certain Western norms but not others. Existing research stipulates that the ‘fit’ between domestic and international norms and values plays a crucial role. Yet our case studies appear to point in a different direction. China had more experience in development and less experience in peacekeeping, but Beijing chose to engage in competitive socialisation of the PKO norm while continuing to contest the MDA norm by proposing alternative development norms, and vice versa for Russia. This indicates that the ‘fit’ explanation of norm internalisation may need to be reworked.

Second, while this article focused on subaltern rising powers (China and Russia), the dynamics of competitive socialisation may be also applicable to cases where the power disparity is larger. For example, the African Union's holistic internalisation of the R2P norm appears to have been driven by the logic of competitive socialisation: by internalising the R2P norm, African leaders hoped to ‘regionalise’ humanitarian interventions and hence to minimise the possibility of Western incursions on the continent.Footnote 117 In light of this, more research is needed to determine how the concept of competitive socialisation can be applied beyond the ‘most likely’ cases of high-capacity actors such as China and Russia.

Acknowledgements

This article was produced as an outcome of the joint research project entitled ‘Coherence or Contestation: Chinese, Japanese and Russian Approaches to the Transformation of Peacebuilding Practices’, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Grant No. 176363, 2018–22). The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous financial support provided by the SNSF. The authors also thank the journal’s editors and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the earlier versions of this article.