Introduction

The last 10 years have seen increasing societal and scientific drive to detect the neurodegenerative diseases causing dementia at the earliest stage, in the hope that, as effective treatments become available (including risk factor modification), it will be possible to ameliorate progression of these diseases and therein delay or prevent dementia onset. Yet, while increasing numbers of people present to health services concerned about memory problems, the percentage leaving memory clinics with a diagnosis of neurodegenerative brain disease is falling.Reference Blackburn, Wakefield, Bell, Harkness and Venneri 1 , Reference Menon and Larner 2

Discriminating clinical presentations which are likely to be due to neurodegenerative brain disease from those which are not is, therefore, an important clinical and research priority. In clinical practice, the assessment process includes interpretation of the patient’s own report of their experience of cognitive difficulties. However, the relationship between self-perceived cognitive decline or inefficiency and brain disease is not straightforward. Subjective cognitive impairment is common in a range of populations, and studies of base rates of cognitive complaints are remarkable for the heterogeneity of results, depending on the cohort and also the questions asked. 3-5 “Do you have a memory problem?” is a very different question from “Is your memory worse than 5 years ago?” and different again from “Is your memory better or worse than other people the same age?” Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) over time is associated with a slightly increased risk of future dementia over people without SCD, especially when tightly defined.Reference Jessen, Amariglio and Buckley 6 Yet, the majority of those with SCD do not progress to dementia, and the presence of subjective cognitive impairment does not appear to correlate with age.Reference McWhirter, Ritchie, Stone and Carson 7

A subjective memory complaints’ (SMC) Likert scale has been used in a number of studies, in which a memory rating of “fair” or “poor” in response to the question “In general, how would you rate your memory?” is used as an indicator of the presence of SMC.Reference Purser, Fillenbaum and Wallace 8 , Reference Paradise, Glozier, Naismith and Davenport 9 Of studies using this scale, Purser et al found that SMC did not predict progression of impairment in Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), and Paradise et al found SMC in 12% of 45 432 adults strongly related to psychological distress but not vascular risk factors.Reference Purser, Fillenbaum and Wallace 8 , Reference Paradise, Glozier, Naismith and Davenport 9 Larner found the same indicator sensitive but not specific for an ultimate diagnosis of functional cognitive disorder (FCD) in patients attending a memory clinic.Reference Larner 10

Around a quarter of people attending memory clinics with cognitive complaints receive diagnoses in keeping with FCDs.Reference McWhirter, Ritchie, Stone and Carson 7 In FCDs, cognitive symptoms are present, and associated with distress and/or disability, as the result of dynamic and therefore internally inconsistent changes in higher cognitive function, rather than progression of neurodegenerative disease.Reference Ball, McWhirter and Ballard 11 Research into FCD diagnosis has concentrated on how we might discriminate cognitive symptoms due to FCD from those due to brain disease. While raw scores on cognitive screening tests seem unhelpful one promising approach has involved analysis of interaction and language in the clinical examination.Reference Reuber, Blackburn and Elsey 12 Another approach, employed in the functional memory disorder (FMD) inventory proposed by Schmidtke and Metternich, examines the frequency and nature of self-reported cognitive complaints.Reference Schmidtke and Metternich 13

In order to interpret the diagnostic relevance of self-reported cognitive complaints, it is important to understand the baseline frequency of comparable experiences in apparently healthy people. However, there have been only a few studies of base rates of specific cognitive lapses in healthy populations. In Jonsdottir et al’s diary study of “action slips” (defined as “actions which we would normally classify as being a sign of absentmindedness”) in 189 healthy adults (mean age 30.8) participants responded a mean of 6.4 “action slips” per week (range 0–30).Reference Jónsdóttir, Adólfsdóttir, Cortez, Gunnarsdóttir and Gústafsdóttir 14 The largest healthy population included in McCaffrey et al’s review of symptom base rates is from a 1987 study including a healthy control group of 620 US college students, of whom 9.7% experienced memory gaps (a gap in memory for an undefined period of time), 23% staring spells, and 27% word-finding lapses.Reference McCaffrey, Bauer, O’Bryant and Palav 15 , Reference Grant, Atkinson and Hesselink 16 Another study included in the McCaffrey review was a 1995 study that included a group of 170 adults (mean age 38) of whom 32% forgot where the car is parked, 17% lost items around the house, and 27% forgot why they entered a room; although 40% of this group had an alcohol use disorder at 10 year follow-up suggesting possible confounders.Reference Demallie, Cottler and Compton 17 There is therefore a lack of up-to-date data on cognitive symptom base rates in unselected healthy adults.

Although there is a well-developed body of research which differentiates the cognitive symptom profile and clinical presentation therein between FCD and people with dementiaReference McWhirter, Ritchie, Stone and Carson 7 there has been little analysis of the questions of how and why cognitive symptoms in FCD differ from cognitive lapses experienced by healthy people during everyday life. These are important questions. Historically, some people within an FCD group have been described as “worried well,” in a way that has dismissed the extent of their cognitive disability and thereby seeming to justify not providing appropriate treatment. At the other end of this spectrum, a pervasive narrative in which subjective cognitive symptoms lie on a “one-way path” to mild cognitive impairment and then dementia means that the fact that cognitive symptoms are really quite common is often lost. As a result, unwarranted prognostic significance may be placed on the presence of cognitive lapses which are a part of normal experience.

Understanding cognitive lapses in healthy adults, and how these are framed in terms of overall self-evaluation of cognitive function (metacognition), is an important preliminary step in the development of more accurate methods of clinical diagnosis and risk profiling in both degenerative brain disease and FCDs. In this study, we therefore aimed to establish the frequency of, and interrelationships between, SMC, specific cognitive lapses, and use of memory strategies, in healthy adults with a low risk of neurodegenerative brain disease.

Methods

An online questionnaire was advertised through a Facebook group for people living within a central area of Edinburgh (in the vicinity of Edinburgh University) with over 30 000 members, described as “a community board for those within walking distance of the Meadows to share resources, tools, skills, information, etc.”

The questionnaire was open from January until late March 2020. Participants between 18 and 60 years were eligible. Exclusion criteria were: self-report of having sought medical advice for memory symptoms or having “ever been diagnosed with dementia or any other memory-related condition.” No incentive was provided for completing the questionnaire. Ethical approval was obtained from Edinburgh University, and no identifying information was collected.

The questionnaire asked participants about their perceptions of their own memory in general (“In general, how would you rate your memory just now?”) using the SMC Likert scale as described by Paradise et al, and respondents were considered to have SMC if they rated memory “Poor” or “Fair” on this scale.Reference Paradise, Glozier, Naismith and Davenport 9 Participants were also asked about their memory in comparison to others and to themselves 1 and 5 years ago, and compared with others the same age.

Participants were asked how frequently they experienced a range of memory lapses, and were also asked whether they experienced each lapse “much more,” “more,” “about the same,” “less,” or “much less” than other people the same age. The questionnaire incorporated all components of the Schmidtke and MetternichReference Schmidtke and Metternich 13 short version FMD inventory (Online Appendix 1). Additional lapses were included following discussion and consensus between the authors. In analysis of cognitive lapses, and of components of the FMD inventory, report of experiencing a lapse “frequently (several times a week or more),” “occasionally (about once a week),” or “rarely (about once a month),” but not “never,” was interpreted as equivalent to “yes” on the FMD inventory.

Questionnaire data were collected with Google Forms, and statistical analyses were performed using Excel (version 2007) and R (v3.6.0). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and Spearman rank correlation coefficient and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used in analyses of nonparametric data.

Results

Demographics

The survey was completed by 124 eligible participants, with a median age of 23 (range 18–59). Seventy-four percentage (92) were female, 24% (30) male, and 1 “other.” 97% (120) were in or had completed further or higher education. Three people self-reported ineligibility by responding “yes” to the question “Have you ever visited the doctor with concerns about your memory?”

General self-evaluation of memory

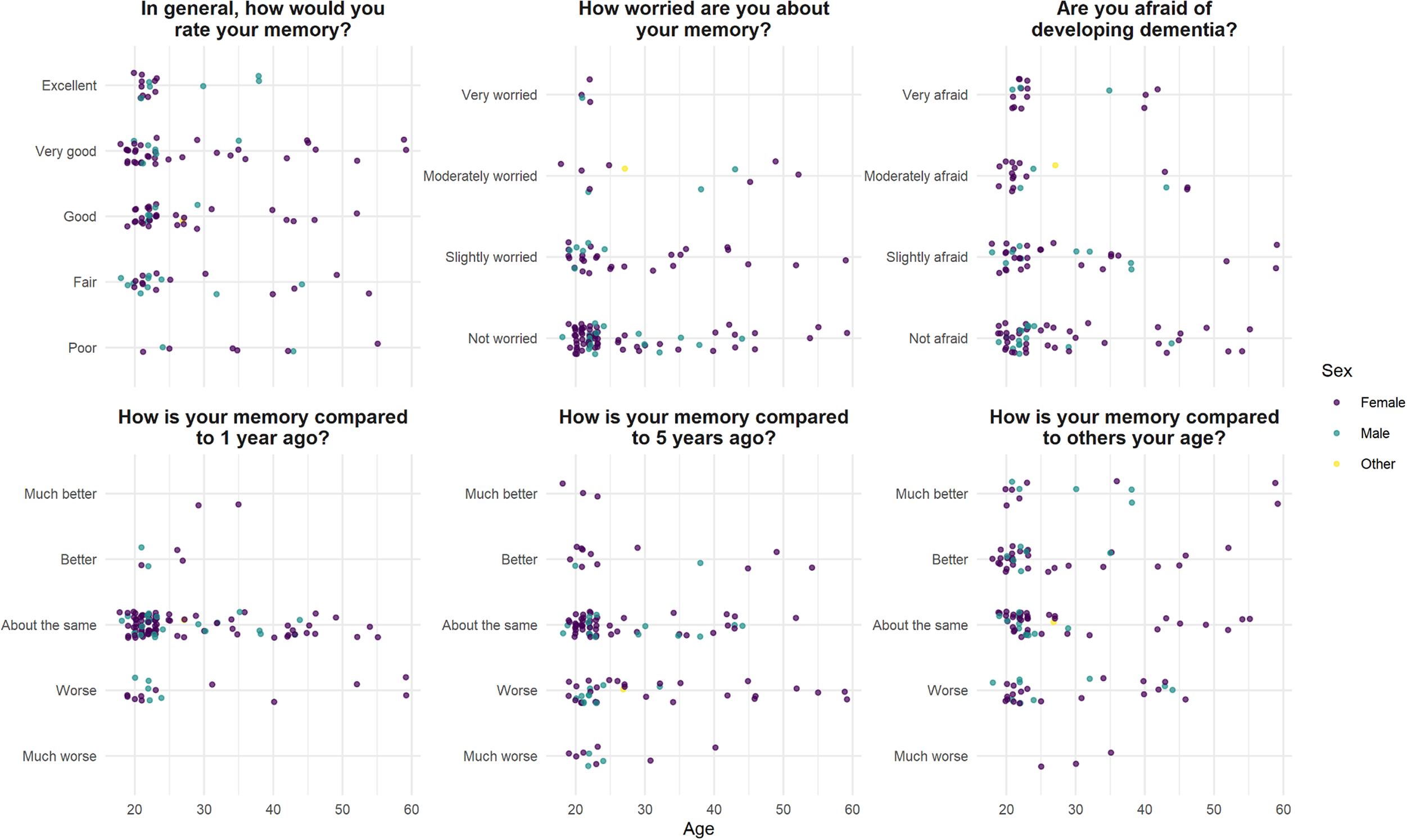

There was no correlation between general rating of memory (the SMC Likert scale) and age (r s = −0.14, P = .12). There was a positive association between perceived memory decline over 1 and 5 years (chi-square test, df = 12, P < .01), but there was no correlation between subjective memory decline over the last 1 or 5 years and age (r s = 0.03, P = .71; r s = 0.11, P = .24); and there was no correlation between memory rating compared to others, and age (r s = −0.07, P = .41) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Self-evaluation of memory function in 124 healthy volunteers, median age 23.

Memory worry and fear of developing dementia

Forty-seven (38%) participants responded “Yes” to the statement “Are you worried about your memory?”; of whom four were “very worried.” Seventy (56%) were “afraid of developing dementia,” including 16 (13%) who were “very afraid.” Neither severity of memory worry nor being “afraid of developing dementia” correlated with age (r s = 0.02, P = .41; r s = −0.06, P = .49) (Figure 1).

Twenty (17%) endorsed the statement “When I forget something I fear that I may have a serious memory problem.” This correlated with memory worry (r s = 0.41, P < .001) but not SMC Likert (r s = 0.06, P = .54) or number of cognitive lapses endorsed (r s = 0.01, P = .99).

Twenty-one (17%) responded “yes” to “Has another person (eg, friends/family) ever expressed concerns about your memory?”

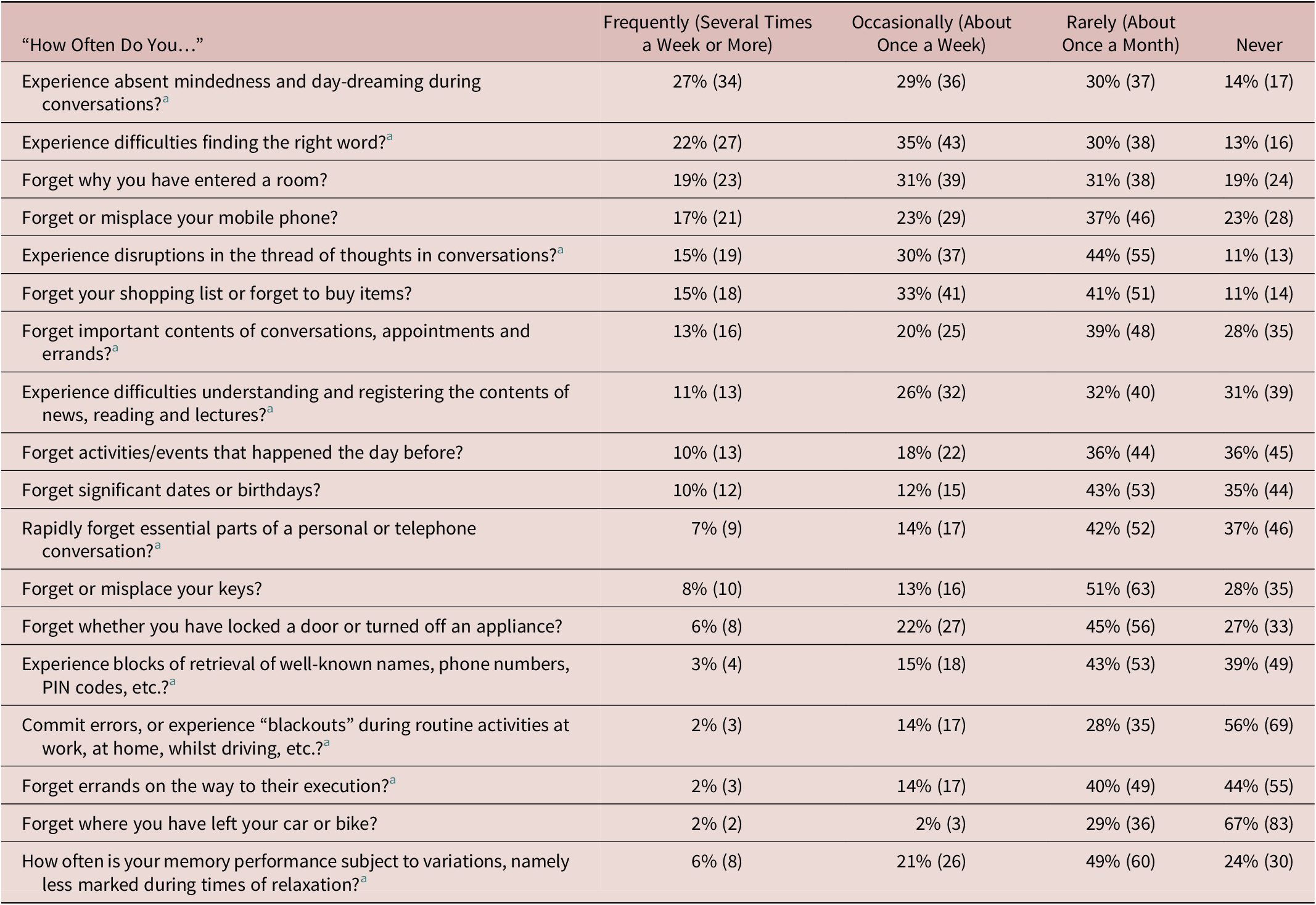

Frequency of specific cognitive lapses

Table 2 shows the reported frequency of cognitive lapses. “Absent mindedness and daydreaming during conversation” was most frequent (several times a week or more in 29% and about once a week in another 28%), followed by word-finding difficulties (at least weekly in 56%), forgetting why one had entered a room (at least weekly in 50%), and misplacing a mobile phone (at least weekly in 40%). Forgetting where one’s car or bike is parked was the least frequently endorsed symptom, but was still experienced at least monthly in 33%.

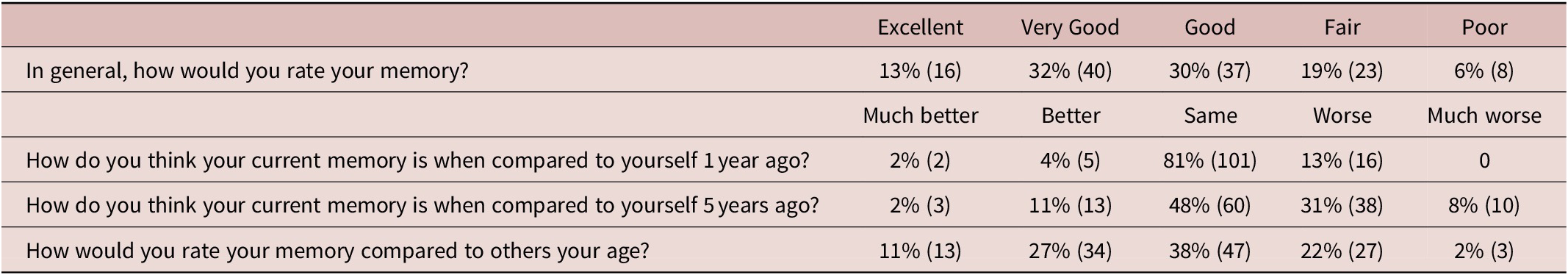

Table 1. Self-Evaluation of Memory.

Note: SMC was common: 25% (31/124) rated memory in general as “Fair” or “Poor” (Table 1).

Table 2. (N = 124) Frequency of Cognitive Lapse/Symptom in 124 Healthy Volunteers, Median Age 23.

a Items included in the FMD short inventory (Schmidtke and Metternich).

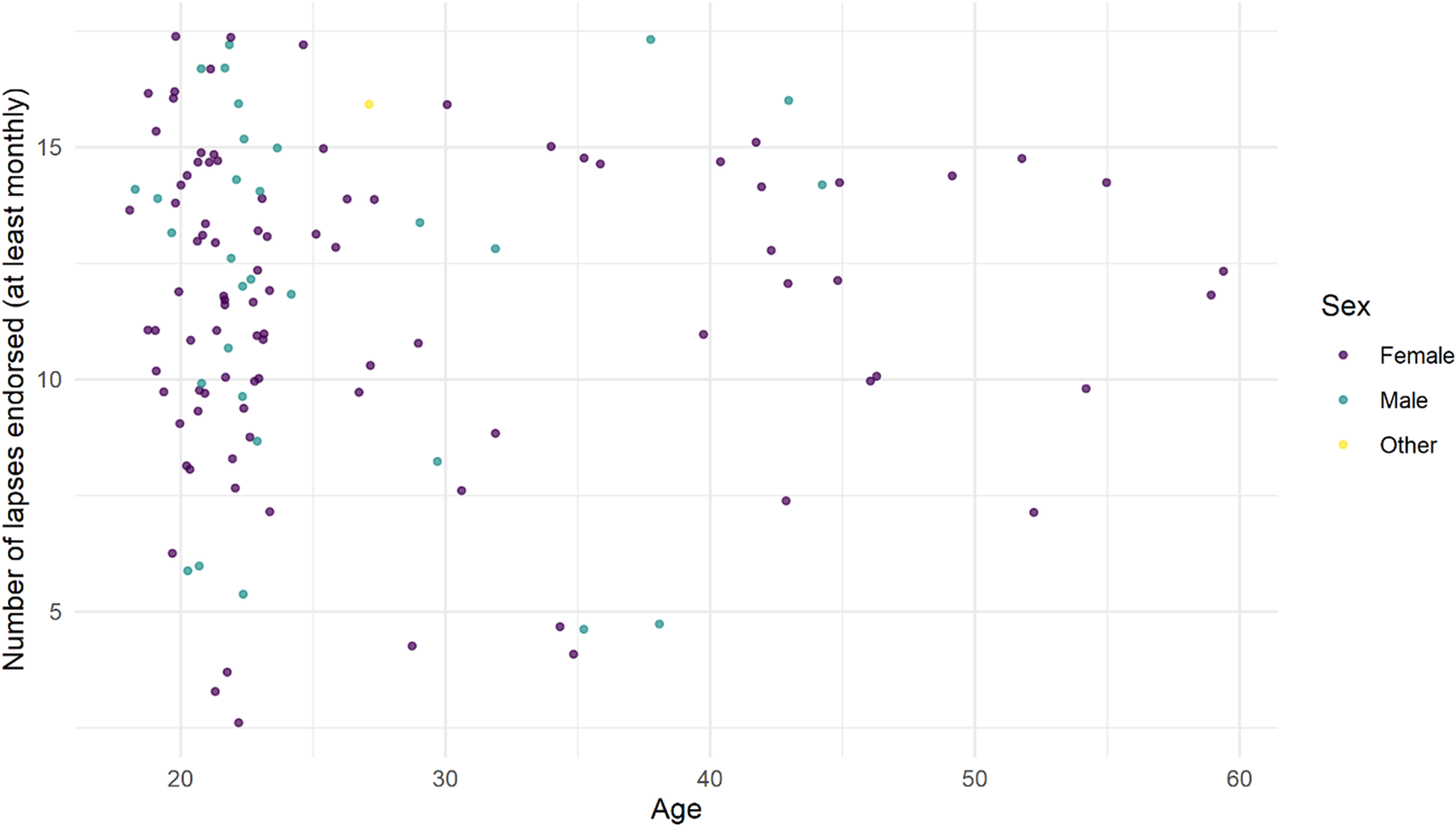

Number of lapses out of 17 (“subject to variation” being excluded) was counted for each participant. Participants with SMC endorsed significantly more cognitive lapses (at least monthly)—a median of 14 compared with 11 in those without SMC (Wilcoxon rank sum test W = 15 376, P < .001). No participant with SMC endorsed fewer than 10/17 lapses. Number of lapses endorsed did not correlate with age (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of memory lapses/17 endorsed in 124 healthy adults, median age 23.

Participants generally (69–97%) reported experiencing the lapses listed in Table 2 as often or less often than others the same age; outliers were “disruptions in the thread of thought during conversations” and word-finding difficulties which 52 (42%) and 50 (40%) respectively reported experiencing more often than others the same age.

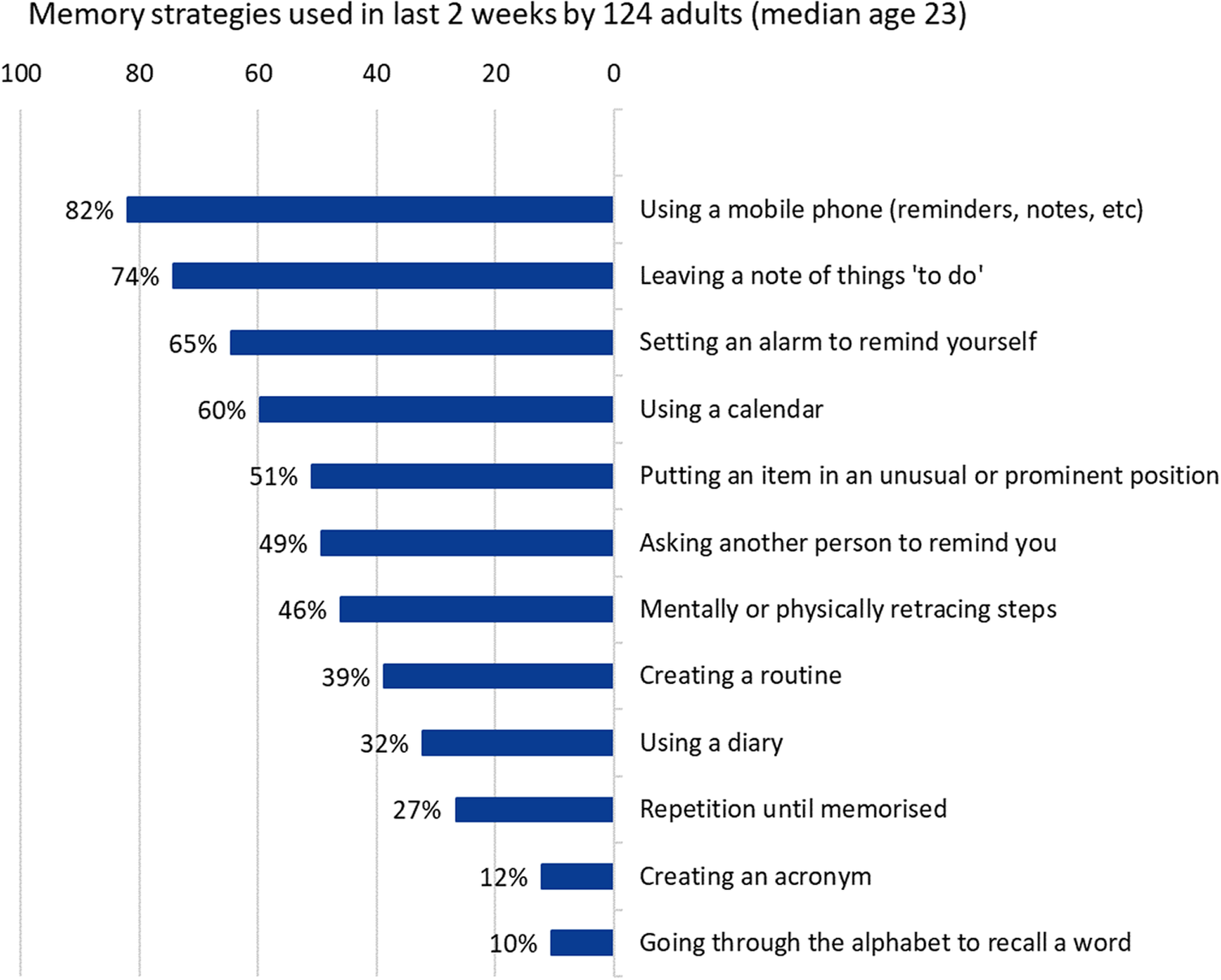

Memory aids and strategies

All participants had used at least one listed memory aid or strategy from those listed within the previous 2 weeks (Figure 3). The most frequently endorsed strategy was using a mobile phone to create electronic reminders or notes (82%). The number of memory aids or strategies used did not correlate with age (r s = −0.15, P = .08). Younger age was associated with greater use of repetition (Wilcoxon rank sum test W = 2098.5, P = .03), but there were no other age associations between specific memory strategies. There was no significant association between the number of aids used and the number of lapses endorsed (chi-square test, df = 140, P = .51).

Figure 3. Memory aids and strategies.

FMD inventory

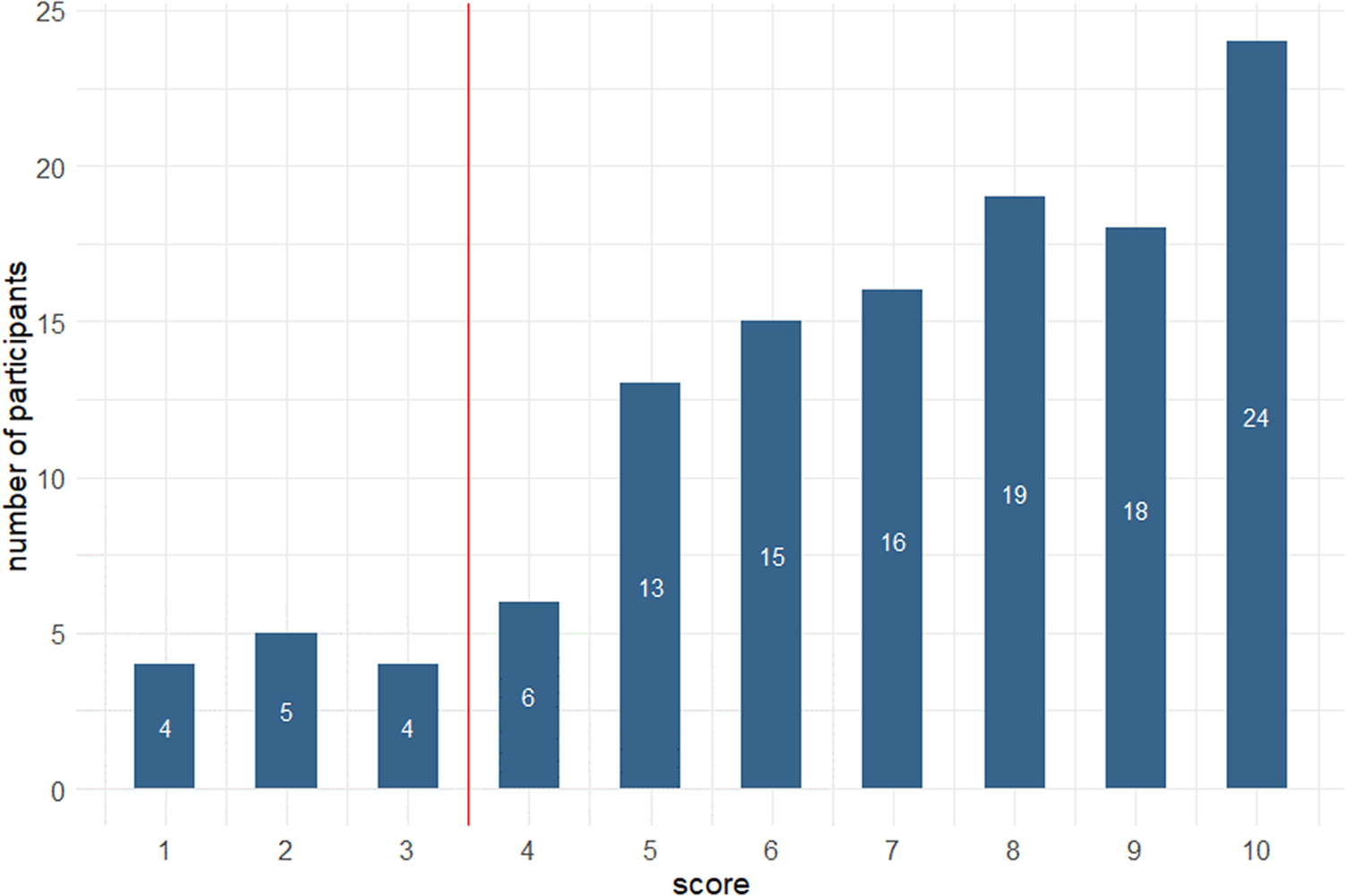

Mean score on the short FMD inventory (Online Appendix 1) was 7 (SD 2.5), and no participant scored zero. Using Schmidtke and Metternich’s suggested cut off score of ≥4, 89% (110) of participants met FMD criteria. Figure 4 illustrates participants’ scores on the FMD inventory. FMD score was inversely correlated with SMC Likert (r s = −0.42, P = .03).

Figure 4. Scores of 124 healthy adults (median age 23) on the Schmidtke and Metternich FMD short inventory.

Given this unexpectedly high proportion of FMD profiles, results were also calculated using an alternative method whereby each symptom was registered as present only if it was experienced at least once per week, instead of at least once per month. Using this method, the mean score was 3 (SD 2.6), and 22 (%) participants scored 0, but 55 (44%) still scored above the ≥4 cut off.

Discussion

The subjective experience of cognitive failure or inefficiency is very common. Using a Likert scale, previously described by Paradise and colleagues, 25% of this population of healthy adults, the majority of whom were in or had completed further or higher education, can be classified as having SMC. 8-10

Perceived decline was also common, with 39% reporting that their memory was “worse” or “much worse” than 5 years previously, and did not correlate with age. However, participants tended to perceive their memory as being as good or better than others the same age, particularly in relation to specific cognitive lapses. This paradoxical combination of perceived cognitive decline alongside “illusory superiority” in comparison to others has also been observed in older adults.Reference Schmidt, Berg and Deelman 18

Much of the subjective cognitive impairment and SCD literature is focussed on older adults, where it is more likely that degenerative brain disease and other pathophysiological processes may impact on cognitive function. However, our previous review of the wider literature found that subjective cognitive symptoms are common, present in a mean of 30% (range 8–80%) of non-clinical populations, and moreover that prevalence does not correlate with age, as would be expected if cognitive symptoms were primarily the result of degenerative brain disease.Reference McWhirter, Ritchie, Stone and Carson 7 The high rate of subjective cognitive complaint and cognitive lapses in this population with a low risk of degenerative brain disease supports a view that the majority of cognitive lapses in the general population are not caused by brain disease. But while degenerative brain disease is overall an infrequent cause of cognitive lapses, they are nevertheless a source of worry. Thirty-eight percentage of our participants were worried about their memory; more (56%) were afraid of future dementia.

Our participants endorsed having experienced a mean of 13 of the 18 suggested cognitive lapses at least once per month, and often several times per week. This is a helpful reminder that frequent memory lapses such as day-dreaming during conversation, walking into a room and forgetting what you went in for, or misplacing your phone are all commonly experienced several times a week by healthy and highly educated adults. That is not to say that these experiences, presenting in a clinical setting, should be dismissed, as in some they may be part of a FCD, associated with cognition-focussed distress and disability, requiring accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Having accurate and age-related data on particular cognitive experiences may be especially helpful in the context of designing specific therapies for FCD. These could be used to help reframe experiences and challenge metacognitions.

In this study, a striking 89% (110) of 124 non-complaining adult participants scored highly enough (≥4) on the FMD short inventory to meet criteria suggested by the authors of that inventory to suggest a diagnosis of FMD had they presented with impairment of function. In Schmidtke and Metternich’s original 2009 validation study the FMD short inventory was administered to 50 healthy controls (mean age 49.5, 50% female) and 45 patients with FMD (mean age 55.2). The control group in the 2009 study had a mean score of 0.8 (SD1) on the FMD short inventory, compared with 7.6 (SD2.6) in the FMD group, giving a specificity of 100% using a cutoff of ≥4 against the gold standard of FMD diagnosis made following non-blinded clinical examination according to the authors’ FMD diagnostic criteria.Reference Schmidtke and Metternich 13 In contrast, the participants in this younger and predominantly female “healthy control” population scored much higher (mean score 7, SD 2.5).

Although our participants were younger and more predominantly female than Schmidtke and Metternich’s healthy controls, and therefore in a group at slightly higher risk of functional neurological disorder, it would be quite wrong to assume that all of those scoring highly on the FMD inventory have FCDs. Allowing for the limitation of self-report, all denied diagnosed conditions affecting memory and none had consulted a health professional for memory problems. Moreover, the 89% (or 44%) scoring above the suggested cut off on the FMD inventory study exceeds the proportion (25%) with SMC. That is, many of our participants endorsed frequent memory lapses of different sorts, even though they overall rated their memory as good, very good, or excellent. This is at odds with our clinical experience of patients with FCDs who are distressed by their symptoms and tend to overestimate their memory deficit.

We would argue instead that this study shows that the memory lapses included in the FMD inventory are experiences that fall within the normal range of experience. As Schmidtke and Metternich’s make clear in the separate FMD diagnostic criteria used as the “gold standard” in the FMD inventory validation study, these experiences become “symptoms” only when they are accompanied by impaired function and distress.Reference Schmidtke and Metternich 13

This study supports a view that abnormalities in metacognition are key to the mechanism of FCD; cognitive lapses are not only experienced, but are experienced as problematic and distressing. In contrast, a large proportion of our population of healthy, highly educated, adults notice, and acknowledge frequent cognitive lapses, without undue worry or concern, whilst also believing their memory performance to be similar to or superior to others. This normalizing (or even illusory superiority) alongside acceptance of failure and inefficiency appears important for healthy cognition.

The population studied here was heavily skewed toward a higher educational background. Most participants were in or had completed further or higher education. We speculate that this group might be expected to perform at a high level in psychometric tests, but also to be accustomed to a degree of self-scrutiny and social comparison against high internal standards. Study of more demographically diverse populations might help us to understand how educational participation and attainment influence both the experience and interpretation of common cognitive lapses.

So while evaluation of the nature and frequency of cognitive lapses has value in the evaluation of FCD in clinic, we suggest that this approach is best used in combination with a broader examination of what the person expects of their cognition, and how they interpret failures; and with other diagnostic methods such as observation and analysis of internally inconsistent patterns of performance and interaction.Reference Ball, McWhirter and Ballard 11 , Reference Reuber, Blackburn and Elsey 12 Future research might usefully examine the basis of and processes through which personal and shared interpretation of experienced cognitive failure and inefficiency might influence cognitive performance; in health, in functional disorders, and in degenerative brain disease.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920002096.

Author Contributions

Laura McWhirter was responsible for study conception and design and for writing the final manuscript. Lachlan King and Eilidh McClure collaborated with Laura McWhirter, Alan Carson, Jon Stone, and Craig Ritchie in designing the questionnaire. Lachlan King and Eilidh McClure collected the data and wrote an early draft of the manuscript. Alan Carson, Jon Stone, and Craig Ritchie contributed equally to study design and subsequent review and revision of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Laura McWhirter, Lachlan King, Eilidh McClure, Craig Ritchie, Jon Stone, and Alan Carson have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare that: Laura McWhirter is funded by a University of Edinburgh Clinical Research Fellowship funded philanthropically by Baillie Gifford. Laura McWhirter provides independent medical testimony in court cases regarding patients with functional disorders. Alan Carson is a director of a limited personal services company that provides independent medical testimony in Court Cases on a range of neuropsychiatric topics on a 50% pursuer 50% defender basis, is an associate editor of the Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, and is the treasurer of the International Functional Neurological Disorder Society. Jon Stone reports personal fees from UptoDate, outside the submitted work, runs a self-help website for patients with functional neurological symptoms (www.neurosymptoms.org) which is free and has no advertising, provides independent medical testimony in personal injury and negligence cases regarding patients with functional disorders, and is secretary of the International Functional Neurological Disorder Society. Professor Jon Stone is a Chief Scientists Office NHS Research Scotland Career Researcher. Craig Ritchie, Lachlan King, and Eilidh McClure declare no conflicts of interest.