Introduction

The last century has witnessed a notable increase in life expectancy in high-income countries such as the United States of America, Canada, Australia, Japan and Western European countries. If this development persists throughout the present century, it is expected that most babies born in 2000 will live to 100 (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Doblhammer, Rau and Vaupel2009). Those life expectancy projections solicit theoretical and empirical attention to understanding of successful ageing and ways to achieve it.

Although the successful ageing model dates back to 1961, when Havighurst (Reference Havighurst1961) introduced the term, the model only gained popularity first when Rowe and Kahn (Reference Rowe and Kahn1987) distinguished between ‘usual’ and ‘successful ageing’. The latter was eventually defined in terms of avoiding diseases and disability, maintaining cognitive and physical functioning, and being engaged with life (Rowe and Kahn, Reference Rowe and Kahn1997), and became a primarily a prominent biomedical model of successful ageing. Psychosocial models of successful ageing emphasise independence, life satisfaction, social engagement, personal growth, adaptability, self-worth, autonomy and social participation (Bowling and Dieppe, Reference Bowling and Dieppe2005), two of which are well known as Selective, Optimisation and Compensation (SOC; Baltes and Baltes, Reference Baltes and Baltes1990) and the Socio-emotional Selectivity Theory (SST; Carstensen, Reference Carstensen1992).

Successful ageing has different interpretations and has been used interchangeably with terms such as ageing well, active ageing, positive ageing, optimal ageing, healthy ageing and robust ageing (Nusselder and Peeters, Reference Nusselder and Peeters2006; Hung et al., Reference Hung, Kempen and De Vries2010; Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Prina, Perales, Stephan and Brayne2013; Katz and Calasanti, Reference Katz and Calasanti2015; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kelly, Kahana, Kahana, Willcox, Willcox and Poon2015), however, it remains unclear what successful ageing is, how it can be measured and how to best achieve it (Strawbridge et al., Reference Strawbridge, Wallhagen and Cohen2002; Depp and Jeste, Reference Depp and Jeste2006). The theoretical successful ageing models have been criticised for paying insufficient attention to the voices of older people, for failing to capture the subjective views of successful ageing from diverse cultural perspectives, for being too narrow to be of use for public health purposes, for being too exclusive and for marginalising those who are not ageing successfully (Martinson and Berridge, Reference Martinson and Berridge2015). A few studies have investigated lay views on successful ageing but to a lesser extent than theory-driven definitions (Phelan et al., Reference Phelan, Anderson, LaCroix and Larson2004; Bowling and Dieppe, Reference Bowling and Dieppe2005; Jopp et al., Reference Jopp, Wozniak, Damarin, De Feo, Jung and Jeswani2015), which has created a gap between theoretical and lay definitions of successful ageing.

It has been suggested that a successful ageing model for all age groups, backgrounds and cultures is not feasible (Martinson and Berridge, Reference Martinson and Berridge2015), especially since the perception and experience of older age has been shown to be influenced by cultures, individual experiences and societal expectations (Löckenhoff et al., Reference Löckenhoff, De Fruyt, Terracciano, McCrae, De Bolle, Costa, Aguilar-Vafaie, Ahn, Ahn, Alcalay, Allik, Avdeyeva, Barbaranelli, Benet-Martinez, Blatný, Bratko, Cain, Crawford, Lima, Ficková, Gheorghiu, Halberstadt, Hrebícková, Jussim, Klinkosz, Knezević, de Figueroa, Martin, Marusić, Mastor, Miramontez, Nakazato, Nansubuga, Pramila, Realo, Rolland, Rossier, Schmidt, Sekowski, Shakespeare-Finch, Shimonaka, Simonetti, Siuta, Smith, Szmigielska, Wang, Yamaguchi and Yik2009; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kelly, Kahana, Kahana, Willcox, Willcox and Poon2015). Additionally, most literature reflects Western perceptions of ageing that define success in terms of individual accomplishments (Torres, Reference Torres1999; Kendig, Reference Kendig2004). Nevertheless, Rowe and Kahn's (Reference Rowe and Kahn1997) definition of successful ageing remains the most widely used, even though it is unrealistic for most people to be disease-free in old age (Bowling and Dieppe, Reference Bowling and Dieppe2005), especially after the age of 75 (Jaul and Barron, Reference Jaul and Barron2017), thus making it harder to attain Rowe and Kahn's criteria for successful ageing (Katz and Calasanti, Reference Katz and Calasanti2015). This specific age group has not been the target of previous reviews (Hung et al., Reference Hung, Kempen and De Vries2010; Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Prina, Perales, Stephan and Brayne2013; Teater and Chonody, Reference Teater and Chonody2019) on the meanings and definitions they attribute to successful ageing, as such reviews have not differentiated between age groups and methodologies, which contributes to the homogenisation of older adults. This is problematic since age-related physiological consequences such as frailty, falls, depression, diseases, sensory loss and disability are more often experienced by the older age groups (Lennartsson and Heimerson, Reference Lennartsson and Heimerson2012; Jaul and Barron, Reference Jaul and Barron2017). Moreover, older adults report more age-related discrimination and stereotyping which can affect their self-perceptions of ageing and successful ageing (Giasson et al., Reference Giasson, Queen, Larkina and Smith2017). Considering current life expectancy developments in most countries, new definitions of older people could be re-examined and re-classified (Ouchi et al., Reference Ouchi, Rakugi, Arai, Akishita, Ito, Toba and Kai2017). Thus, the present study aimed to review systematically the perspectives of successful ageing from the viewpoint of 75+ older adults, as reported in qualitative, quantitative and mixed-design research, and the factors that facilitate or hinder one's ability to age successfully.

Methods

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed, and the search was conducted in collaboration with an experienced medical librarian (see Table S1 in the online supplementary material). The search strategy was based on keywords and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms adapted to suit each database, following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). The systematic review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (No. CRD42019140994).

PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Scopus online databases were searched between October and December 2018 and updated on 18 January 2020. All peer-reviewed articles published before January 2020 were eligible for inclusion. The following search terms were used: (a) successful ageing or synonyms of the concept such as optimal ageing, ageing well, positive ageing, healthy ageing and active ageing (used with both American and British English spellings); and (b) perception or view, definition, attitude, self-rated, opinion and interpretation, in both singular and plural forms. Subsequently, these terms were combined into (a) and (b). All fields, MeSH terms and wild card symbols were used to ensure all keyword variations. The process was repeated across all the databases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

After removing duplicates, two of the authors (ACB and EMT) independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles for full-text extraction. Through the snowballing method, references of relevant articles were manually screened to ensure that all relevant articles were found. Any disagreements regarding the inclusion of studies were resolved by discussion. We included:

(1) Original qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods peer-reviewed journal articles focusing on the lay views of older people aged 75 and above. Articles were considered qualitative if participants were asked open-ended or semi-open-ended questions in an interview or focus group, quantitative if they included a survey or questionnaire, which generates measurable statistics that aimed to quantify the opinions and attitudes of the research participants of what it means to age successfully. Mixed-methods studies were characterised by the combination of at least one qualitative and one quantitative research component for the purpose of gaining a deeper understanding of the successful ageing concept.

(2) Studies involving age groups 60 years and above, only if a separate analysis on the views of older people aged 75 and above was reported.

Additionally, we excluded:

(1) Non-peer reviewed articles such as book chapters, dissertations, review articles, opinion papers, and clinical or intervention studies.

(2) Studies without a distinct interpretation of the views of older adults aged 75 and above.

Data extraction

The authors extracted data on a standardised form developed for this review. Extracted data included author(s), title of article, date of publication, continent, country of study, population, study aim/research questions, sample characteristics (age, age range and mean age per gender), methodology, measures, analysis and results.

Data analysis and synthesis

As the articles identified were mostly qualitative and comparable, data were analysed through a narrative synthesis using thematic analysis (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers and Britten2006); Snilstveit et al., Reference Snilstveit, Oliver and Vojtkova2012). Themes of successful ageing created by study authors and direct quotes from study participants from the reviewed studies were identified, extracted, coded and analysed, using Microsoft Word and NVivo 12 (QSR International, Melbourne). If the themes were clearly stated, they were extracted as they were; otherwise, two of the authors (ACB and HH) generated new themes inductively (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) based on the explanations provided by the authors of the particular study. Two researchers (ACB and HH) worked on the data extraction and thematisation, which consisted of grouping sub-themes into overarching themes. Our synthesis involved integrating and aggregating findings from multiple studies into new broader themes. Disagreements were resolved through regular meetings and deliberations.

Assessment of methodological quality

A quality appraisal of included studies was conducted independently by two of the authors (ACB and HH) and checked by the last author (EMT). All the studies were quality-appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau, O'Cathain, Rousseau, Vedel and Pluye2018) which has been designed to assess multiple types of study designs, including mixed-methods, quantitative and qualitative studies. There are five scoring items with answers of ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘cannot tell’, and a comments section for reviewers’ explanations. The current study aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the lay views of successful ageing among older adults aged 75 and above. Due to the limited number of articles conducted in the field the subject matter (the lay views of successful ageing) was considered more important than the quality of the study's methodology. Thus, no studies were excluded based on methodological quality. However, if we had identified inadequately reported studies, we would have excluded them from the analysis. The details of the quality appraisal of the individual studies are provided in Table S2 in the online supplementary material.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

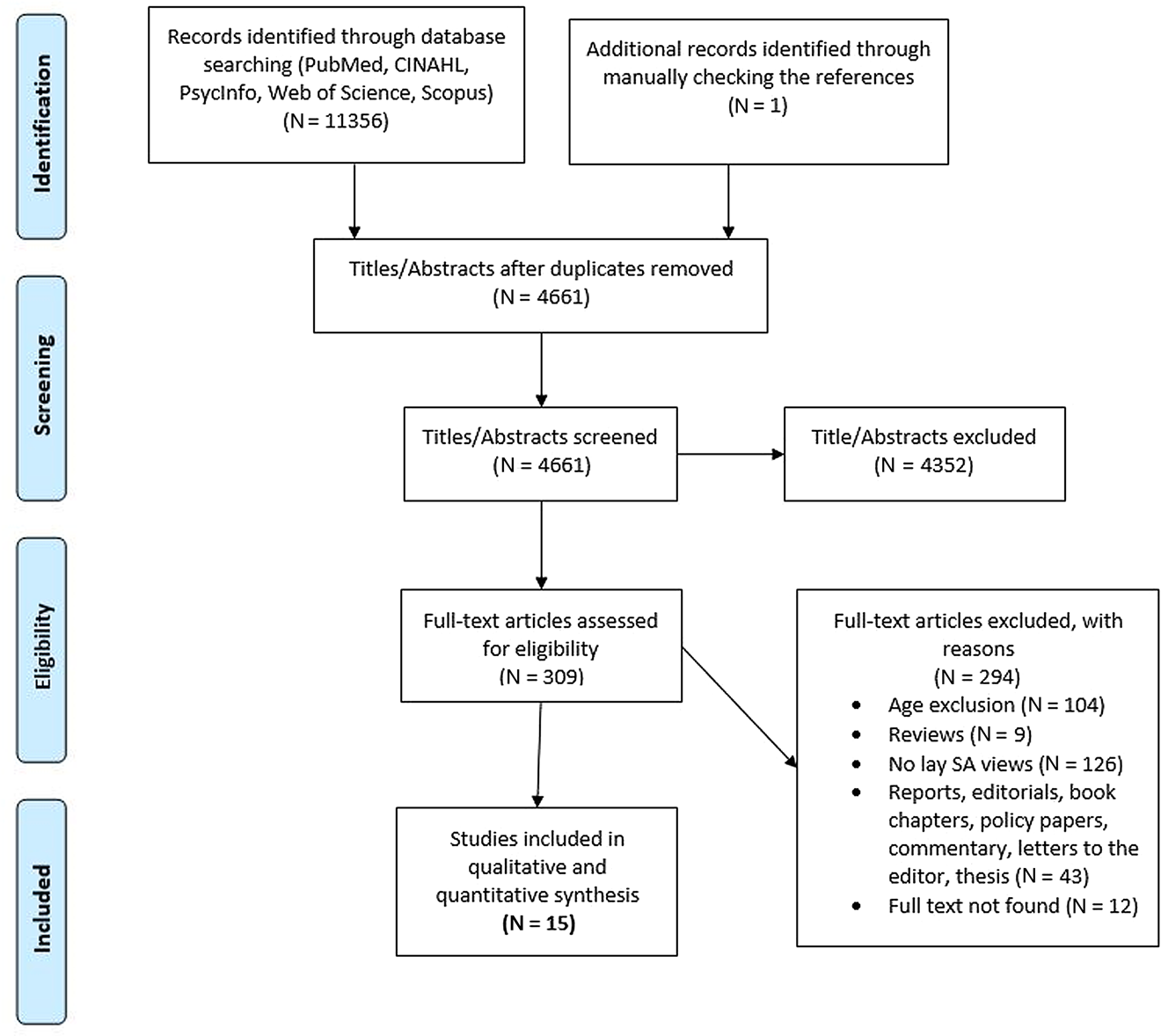

The literature search identified 11,356 articles published until January 2020, as presented in Figure 1. After duplicates had been removed, the titles and abstracts of 4,661 articles were assessed for eligibility, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The title and abstract screening resulted in 309 articles for full-text reading. By applying the exclusion criteria, 294 articles were excluded after the full-text screening: 104 articles were excluded based on age, nine because they were reviews, 126 as they did not look at successful ageing from the lay views, 43 because they were non-peer-reviewed papers (reports, editorials, book chapters) and 12 as the full text was not found (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Literature search PRISMA flow chart.

Note: SA: successful ageing.

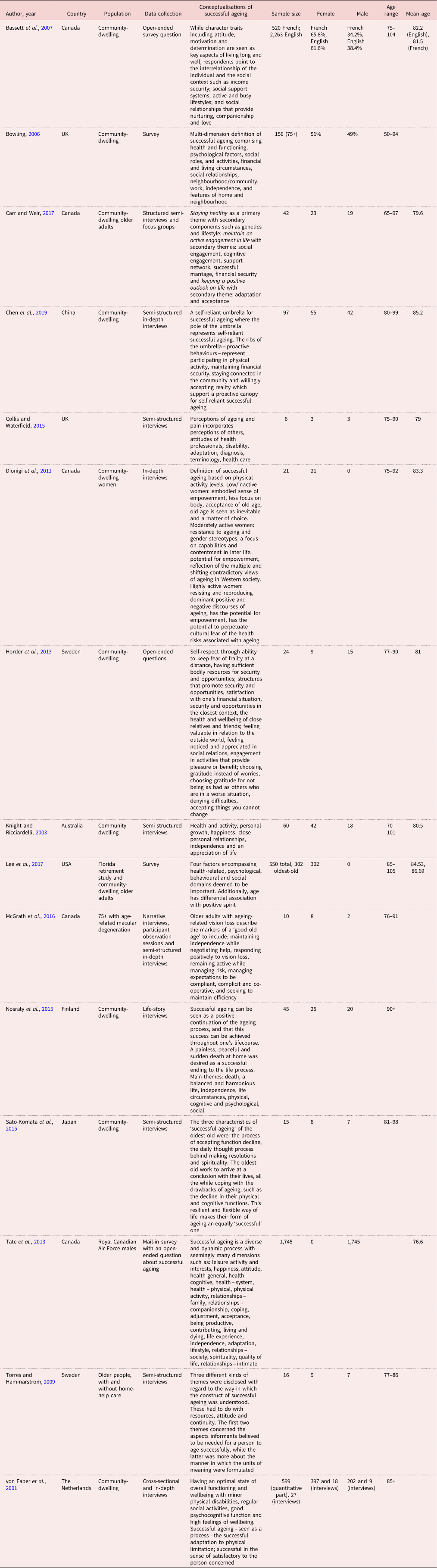

Thus, 15 articles published between 2001 and 2019 with sample sizes varying between six and 1,745 were included. Most of the participants in these studies were male, accounting for 56.5 per cent of the total population sample, as shown in Table 1. The included studies mostly covered high-income countries.

Table 1. Study characteristics

Notes: UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Findings

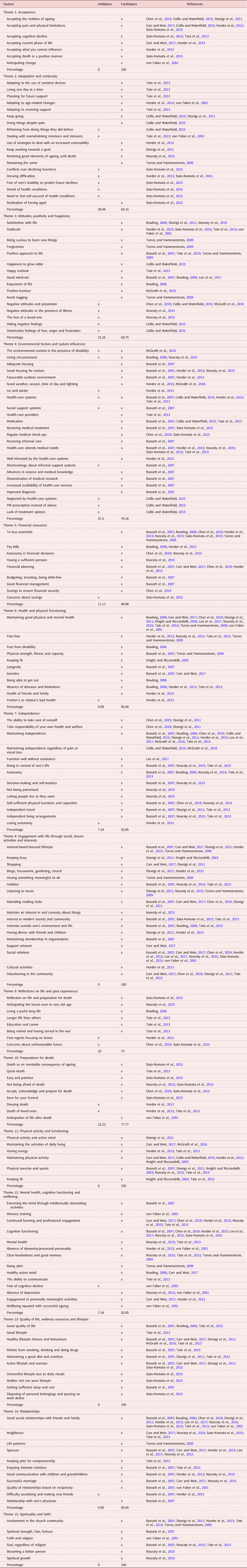

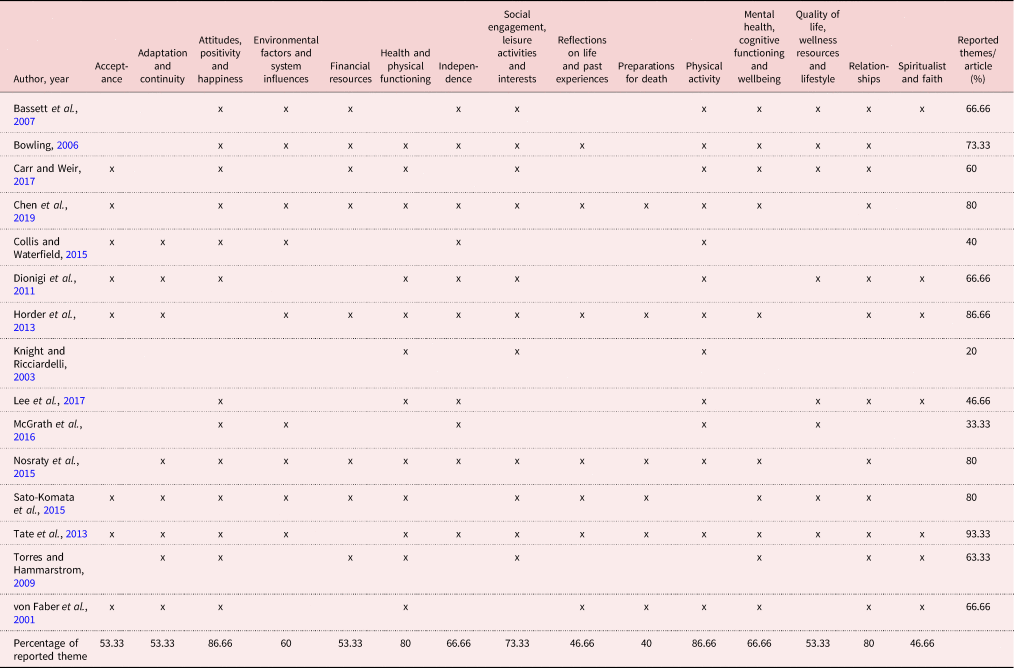

Upon completing the thematic analysis, we identified 15 themes of successful ageing across the 15 articles included in this review. Each theme comprises factors that can act as facilitators and/or as inhibitors to successful ageing. We found that facilitating factors were most reported in all the themes (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Factors, barriers and facilitators of successful ageing

Table 3. Frequency of themes

Several facilitators were reported in each theme, ranging from six to 19 (in themes 1 and 3) and inhibitors between none (theme 7, 9, 11 and 13) to nine (theme 3). The identified 15 themes consisted of aggregates of factors extracted from the 15 articles.

Theme 1: Acceptance

This theme was found in eight articles. Acceptance is understood as ‘the mental recognition that personal circumstances change over time, and that one has accepted and come to terms with these changes’ (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). The importance of accepting the realities of ageing was noted (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019). This includes accepting the pain and physical limitations that come with age (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017), as well as cognitive declines (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015). It also extended to accepting current phases of life, situations and abilities (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017) and anticipating change (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001). Acceptance was related to uncontrollable events such as death (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015) and illness of friends and relatives (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013).

Theme 2: Adaptation and continuity

Adaptation and continuity were closely related and were reported in eight articles. Adaptation was defined in terms of adapting to the changes that occur in the process of ageing (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). This includes the use of assistive devices (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), living one day at a time, moderation, planning for future support (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), keeping going (perseverance) (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011) and receiving support when needed (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). In other studies, adaptation also meant people doing things despite being in pain, refraining from doing things they did before due to the risk of falling (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015), and dealing with personal stressors and overwhelming emotions (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). Moreover, strategies to deal with an increased vulnerability in relation to one's own body and one's immediate surroundings were also mentioned (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). Continuity meant continuing to work towards a goal (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011), persevering despite pain (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015), retaining good elements of ageing until death (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015) and simply remaining the same (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009).

Finally, some authors reported conflicts over declining functions and denying difficulties (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015). These included the sensation of loss of physical and cognitive functions, fear of one's inability to predict future declines, the acceptance or denial of health conditions, the need to feel self-assured of one's health condition and the realisation of having aged (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015).

Theme 3: Attitudes, positivity and happiness

Thirteen studies mentioned attitudes, both positive and negative, as a component of successful ageing. In terms of positive attitudes, studies reported satisfaction with life (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015), gratitude (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015), as well as being curious about learning new things and forgiveness (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009). In the same vein of positivity and happiness, a positive approach to life (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), happiness about growing older (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015), a happy outlook (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), a good mind-set (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017) and enjoyment of life (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006) were reported. This positive approach is occasionally paralleled by a denial of difficulties and avoiding nagging (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015). Other studies mentioned the importance of remaining positive despite disability, diseases, physical decline and negative life events (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017). Combating these negative life events with positive humour was deemed a good strategy (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016).

Negative attitudes were also reported. Some studies mentioned negative attitudes and pessimism (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019) in the presence of illness, pain, the loss of a loved one and due to past life experiences (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015). These life events mitigate against successful ageing (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015). Others mentioned hiding negative feelings from others to avoid being perceived as complainers, an old-age stereotype. Moreover, one study mentioned the feelings of fear, anger and frustration to maintain a false sense of happiness to loved ones and care staff (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015).

Theme 4: Environmental factors and system influences

This theme was reported in nine articles. The environmental context in the presence of disability (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016) and the living circumstances (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015) were mentioned as important determinants to successful ageing. These could enhance opportunities and safety but also could be hindering in nature (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). In some studies, home-ownership, adequate accommodation and access to good housing for seniors were considered important (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015). While some people wanted to stay in their own home as long as possible, others believed that moving to a seniors’ residence provides security: ‘Well, the first condition is to stay fit enough to be able to live on your own. And to live at home; I'd much rather live here at home than in some institution … (5, male, living alone, receiving daily home help)’ (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015, p. 54). Apart from living arrangements, a favourable outdoor environment was reported (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013), which included weather (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016), season, time of day and lighting (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016). However, ice and snow in winter can become a threat to successful ageing as they impede people from staying active (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013).

System influences included health care (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015) and social support systems (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007). These comprised health-care providers (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), medication (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015), receiving medical treatment (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015), going for regular medical check-ups (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019) and receiving informal care (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007). Advances in science and medical knowledge, the dissemination of medical research and increased availability of health-care services (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007) were also seen as determinants of successful ageing.

Older adults expected that health care would attend to their medical needs (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015). Additionally, awareness and information by the health-care systems about older adults’ medical conditions contributed to the feelings of security and health (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). In cases of disability, participants reported valuing compliance with the requirements of the care staff. These included refraining from travelling alone and using the stove, and only using taxis for transportation (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016).

While the importance of health care was noted, some participants felt neglected by the health-care systems through a lack of advice on the premise that their pain was a natural result of ageing (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015). Some others felt frustrated that their condition did not improve, despite regular visits to the hospital (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015), and with lack of treatment options (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015). Others reported that they were prescribed pills instead of receiving advice: ‘I don't know if you are given a lot of advice now, apart from … given tablets … I think you used to get more advice’ (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015, p. 24). In general, the shortcomings of informal support systems were noted: ‘A sense of caring for seniors is absent in our community today’ (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007, p. 123).

Theme 5: Financial resources

Eight studies included the theme of financial resources. Financial resources were needed to buy essentials (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), pay bills (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013) and retain autonomy in financial decisions (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019) – ‘Money doesn't buy happiness, but it helps to buy the support you need to live well’ (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007, p. 122). Financial resources were discussed in the context of having a sufficient pension, as stated by a Finnish female: ‘Well, health of course and then sufficient income. I mean that your pension is enough to cover all medical costs and the like’ (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015, p. 54). Besides making ends meet, financial planning (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), budgeting, investing, being debt-free and good financial management were also reported as determinants of successful ageing (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007). Financial concerns about the future, and hence worries about savings (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015), were also reported, as savings were seen as a way to ensure financial security in case of major illness (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019).

Theme 6: Health and physical functioning

Twelve out of 15 articles mentioned this theme. Health and physical functioning meant maintaining good physical and mental health (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003; Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019). The latter is believed to facilitate one's ability to engage actively in life (Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017), pain-free (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015) and free from disability (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006). Additionally, some studies emphasised the importance of physical strength, fitness and capacity (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009), keeping fit (Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003), longevity (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007), genetics (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017) and ‘being able to get out’ (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006) as important determinants of successful ageing.

For some, health meant the absence of diseases and limitations (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). For others, health was seen as a resource for being active and participating on a personally desired level, despite the presence of disease and disabilities (Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). Not surprisingly, some participants valued their personal health almost as much as they valued the health of friends and family (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). Partners’ or relatives’ ill-health was seen as a reason for sadness and worries. The dependency on immediate relatives’ health, with partner care-giving, was seen as a barrier to engaging in activities and a threat to personal freedom, but a spouse's death was seen as an even bigger threat (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). Additionally, some considered a degree of morbidity to be part of the natural ageing process (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015).

Theme 7: Independence

This theme was reported in ten articles. Independence referred to the ability to take care of oneself (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), to take responsibility for one's own health and welfare (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011) and maintain this independence (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019) despite pain (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015), while requesting help if needed (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016), but also the ability to function well without assistance (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017).

The importance of being in control of one's life was highlighted (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015) in terms of financial capacities (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), autonomy (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015), self-reliance (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), decision-making and self-mastery (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015), ‘not being patronised’ and ‘letting people live as they want’ (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015).

Independence also meant being self-sufficient in terms of physical functions and capacities (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), routine activities (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), living arrangements (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015) and travel by driving a car or by flying (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). When autonomy equated respect for some (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007), losing one's autonomy when close to death triggered insecurities (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). As such, with vision loss, preserved independence was seen as the most important aspect to ageing successfully (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016).

Theme 8: Social engagement, leisure activities and interests

Eleven studies defined successful ageing in terms of an engaged interest-based and leisured lifestyle (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017). Studies reported such factors as keeping busy (Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011) through shopping (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017), bingo, housework, gardening and attending church (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). The importance of having something meaningful to do was noted (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009) in terms of hobbies (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015) such as listening to music (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015), keeping up with advances in technology (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009) and attending reading clubs (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019). It was evident that older people wanted to ‘maintain an interest in and curiosity about things’ (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015) in modern society and their community (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015), as well as outside their own environment and life (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013).

Theme 9: Reflections on life and past experiences

Seven studies mentioned this theme. This included reflections on life and past experiences (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015). In this theme, reflecting on life (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015) also included anticipating the future even in very old age (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015), which even extends beyond death (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001). In some studies, living a joyful long life (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006), even longer than others (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), also seemed to be important. Certain life experiences were associated with successful ageing, such as education and career, being retired and having served in the Second World War (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). Looking back to past experiences generated some nostalgia among participants who thought ‘things were better in the past’ (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015).

Retrospection has its share of regrets and focus on losses (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). While recalling past experiences, some participants prepare for the future by sharing thoughts with their family and friends (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015). This, in some cases, also brought up concerns and worries about the unforeseeable future (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), which were seen as a threat to successful ageing.

Theme 10: Preparations for death

This theme was mentioned in six articles. While life has its shares of hopes and concerns, death and dying were seen as an inevitable consequence of ageing and some studies stressed ideas about an easy, painless (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015) and quick death (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). Ageing successfully meant not being afraid of death (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015), but also accepting, acknowledging and preparing for death (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), as illustrated in this quote: ‘When I was a younger, I didn't like the idea of dying, but now, I'm not so afraid anymore’ (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015, p. 590).

Regardless of fear of death or its acceptance, some made preparations for the future and saved for their funeral (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015) and others anticipated life after death (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001). Some displayed denial and laughed when death was mentioned (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013). The death of loved ones seemed to be a threat to their successful ageing (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013).

Theme 11: Physical activity and functioning

Thirteen articles defined successful ageing as being mentally and physically active (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003; Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019). For highly active women, physical activity and an active mind are key components of successful ageing (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011). Not surprisingly, age differences were observed in relation to what ‘being active’ means. For 75+ older adults, it meant volunteering, while for the oldest-old (85+) being active referred to maintaining the activities of daily living (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017).

Having energy (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), maintaining physical activity (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), remaining active (Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017), despite pain (Collis and Waterfield, Reference Collis and Waterfield2015), were important physical factors for having an active life. Personal growth (Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003) through physical exercise and sports (Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015) and keeping fit (Knight and Ricciardelli, Reference Knight and Ricciardelli2003; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013) were also mentioned.

In the presence of visual loss, the use of several coping and adaptive strategies to facilitate engagement in the community, minimise risk and reduce the experience of disability was discussed. These strategies included asking for help, being careful, concentrating and completing tasks slowly (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016).

Theme 12: Mental health, cognitive functioning and wellbeing

Ten articles mentioned mental health and cognitive resources as an important component of successful ageing. Prerequisites for successful ageing were identified as cognitive functioning (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), mental health (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015), absence of dementia, preserved personality (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013), clear-headedness, having a good memory (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015), being alert (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009), being healthy and having an active mind (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017), and the ability to communicate (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013).

While some participants feared cognitive decline due to perceived loss of personality (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001), others accepted their cognitive decline and accepted that they had aged (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019). Participants also believed that mind exercises (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007), such as intellectual stimulation and memory training (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001), continued learning and professional engagement (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), inquiry and curiosity were thought to lead to improved cognitive abilities (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007). Additionally, social engagement was related to cognitive engagement as social interaction was believed to keep one's mind stimulated (Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017). Finally, the absence of depression was also reported (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015), especially that wellbeing was equated with successful ageing (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001). The equation is conditioned by personality and character traits since they contribute to achieving and maintaining the feelings of wellbeing (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001).

A desired level of engagement in personally meaningful activities contributes positively to one's ability to age successfully (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017).

Theme 13: Quality of life, wellness resources and lifestyle

This theme was found in eight of the reviewed articles. Having a good quality of life was mentioned in three studies (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). This encompasses both a good lifestyle and the provision of basic needs; as an 82-year-old participant put it: ‘Being well fed, well clothed, and well housed [QL2]’ (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013, p. 310).

Six articles mentioned lifestyle factors and choices as being important for ageing well. These factors refer to healthy lifestyle choices and behaviours (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laliberte Rudman, Polgar, Spafford and Trentham2016; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017). They included refraining from smoking, drinking and taking drugs (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), maintaining a good diet and nutrition (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), and having an active lifestyle and doing exercise (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017). Some participants described successful ageing as a lifestyle maintained with daily rituals (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015), being neither rich nor poor (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015), or getting sufficient sleep and rest (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007). Additionally, some considered preparing for new lifestyles by disposing of personal belongings and passing on work duties (Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015). Wellness resources were defined as having good physical and general health, intact cognitive functioning and independence, and being able to think clearly (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017).

Theme 14: Relationships

This theme was present in 12 out of 15 studies. Older adults defined relationships as being engaged in and maintaining good social relations with others, such as friends and family (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), neighbours (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Sato-Komata et al., Reference Sato-Komata, Hoshino, Usui and Katsura2015; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017), life partners (Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009), spouses (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017) and keeping pets for companionship (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013). This theme also meant having dinner with friends and children (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013), maintaining memberships in organisations (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007), support networks (Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017), participating in cultural activities (Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013) and volunteering in the community (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019).

Social relationships are crucial for successful ageing in terms of keeping one's mind stimulated (Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ye and Kahana2019), maintaining good social interactions and relations (Bowling, Reference Bowling2006; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017), enjoying intimate relations (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), and maintaining good relationships and communication with children and grandchildren (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015). While support networks (Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017) and successful marriage (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015; Carr and Weir, Reference Carr and Weir2017) are a result of good social engagement, the quality of relationships based on reciprocity (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001; Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007), respect, kindness, love, trust, understanding and loyalty (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007) were also valued.

While, it is not always easy to socialise and make new friends in old age (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013), keeping a continuous and sustained relationship with one's physician was also seen to contribute to a long and healthy life (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007).

Theme 15: Spirituality and faith

This theme was found in eight studies. In some studies spirituality refers to involvement in the church community (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Torres and Hammarstrom, Reference Torres and Hammarstrom2009; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Bellamy2011; Horder et al., Reference Horder, Frandin and Larsson2013; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013), but spirituality also referred to spiritual strength (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017), spiritual health, fate, fortune (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007), and faith or religion (von Faber et al., Reference von Faber, Bootsma-van der Wiel, van Exel, Gussekloo, Lagaay, van Dongen, Knook, van der Geest and Westendorp2001). Believing in god regardless of religion was seen as an important factor of successful ageing (Bassett et al., Reference Bassett, Bourbonnais and McDowell2007; Tate et al., Reference Tate, Swift and Bayomi2013; Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015). Spiritual growth and becoming a better person by accepting others were reported as crucial components of successful ageing (Nosraty et al., Reference Nosraty, Jylha, Raittila and Lumme-Sandt2015).

Discussion

The present study reviewed the perceptions of successful ageing among older adults aged 75 and above, by providing a synthesis of the research on diverse older adults’ meanings of successful ageing. Within the 15 thematic definitions identified, the components of successful ageing were categorised into contributing facilitators and inhibitors. Facilitators were more often reported than barriers, which can be explained by the fact that the term successful ageing is positively charged, and therefore older adults associate positive attributes with this term. These findings are supported by the idea of constructing a positive narrative by pointing out the positives associated with ageing, since the term ‘successful ageing’ was first introduced to counter ageism and age stereotyping caused by the overall discourse of decline (Rowe and Kahn, Reference Rowe and Kahn1997; Calasanti, Reference Calasanti2015).

It is acknowledged that successful ageing may be achieved even in the presence of chronic diseases and disabilities (Phelan et al., Reference Phelan, Anderson, LaCroix and Larson2004; Young et al., Reference Young, Frick and Phelan2009). The components identified in the reviewed studies support this claim and highlight the multi-dimensionality of successful ageing. Specifically, regardless of the country and study design, the reported themes in the reviewed studies show that older adults’ beliefs about successful ageing are captured in more than health-related statements and include beliefs about psychological health, social relations, positivity and optimism, adaptation and acceptance of age-related changes, finances, spirituality and environmental influences, which is in line with previous research (Phelan et al., Reference Phelan, Anderson, LaCroix and Larson2004; Iwamasa and Iwasaki, Reference Iwamasa and Iwasaki2011; Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Prina, Perales, Stephan and Brayne2013). Additional themes and components, which may be more age-dependent, and specific for the older adults 75 and above, were also found to be important for successful ageing. In this review, three novel successful ageing-related themes such as reflections on life and past experiences, preparations for death and environmental and system influences emerged. The first two have rarely been mentioned in previous reviews on successful ageing but it was reported in more than half of the studies reviewed in the current work. Reflecting on life, past experiences and anticipating the future seemed to be important for older adults. While certain life experiences such as career and education were considered to contribute to successful ageing, also living a joyful long life was deemed important by older adults. Regarding death, 75+ older adults reported wishes for an easy and painless death. The association between time left in life and chronological age might suggest that younger and older adults’ definition of successful ageing is not the same, potentially due to perceived closeness to death and age-related differences in social goals. According to the SST, when time is perceived as limited, emotional goals and positive emotions become more important, even when associated with death (Carstensen et al., Reference Carstensen, Isaacowitz and Charles1999; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kahana and Kahana2017). That is why older adults favour present-oriented goals that maximise wellbeing, such as investing in positive relationships with loved ones. In fact, having good social support and close relationships, a frequently reported theme that was also found in most of the reviewed studies, could be associated with declines in death anxiety over time (Chopik, Reference Chopik2017).

The second emergent theme is the environmental and system influences. This includes social and health-care services as well as living circumstances. While having access to medical services and receiving medical care were seen as important factors, some studies reported that participants felt neglected by the health-care systems and did not receive appropriate advice on the premise that their health problems are a natural cause of ageing. Considering the age group and the increased risk and fear of falling (Jung, Reference Jung2008), favourable weather, season and lighting become relevant contributors to successful ageing, while ice and snow become a threat to successful ageing as these factors would impede older adults staying active. Environmental factors become more important as older adults move from early old age to an older phase in their life. The two themes of life and death, and environmental and system influences show that perceptions of successful ageing for older adults aged 75+ are not necessarily the same as those of younger counterparts. This study then highlights this difference in the perceptions of successful ageing, especially in relation to increased age-related vulnerability and closeness to death.

The theme of environmental and system influence alluded to some form of ageism experienced in health-care settings, in addition to some forms of system support. The remaining themes address successful ageing in terms of agential capacities (positive attitude, exercising and self-control), which translate into actions and behaviours on the part of older adults. Through the differing conceptions of successful ageing presented in these 15 articles, we reiterate the critical issues presented in Katz and Calasanti (Reference Katz and Calasanti2015). Successful ageing is still defined, even among the 75+ older adults, as a lifestyle choice that is associated with behaviours and volitions. These are occasionally constrained by material conditions and cumulative advantages and disadvantages. A wealth of critical literature in social gerontology has highlighted the struggle in applying a normative concept of successful ageing to a diverse older population (Martinson and Berridge, Reference Martinson and Berridge2015), as age, gender, race and other life chances intersect to shape opportunities and inequalities in older age. However, it seems that even the oldest adults across cultures and backgrounds are accepting a larger share in their responsibility to age successfully, with diminishing state responsibilities.

This systematic review has some limitations. No grey literature was searched and therefore other relevant research might have been missed. Despite the methodological strategy to be more inclusive, due to the small samples and lack of studies conducted in the field, we were not able to highlight successful ageing views in relation to various socio-economic factors and could not capture the views of older adults from disadvantaged communities and settings. Another limitation of the field is that most studies are conducted in countries with high life expectancies, meaning that cultural variation may exist, suggesting that more research should be conducted. Furthermore, the sample size of many of the included studies was small and is therefore probably not generalisable to the whole population under study.

Research and policy directions

Our results highlight that the views of older adults aged 75+ are not to be condensed to those of their younger counterparts. More research should be conducted towards understanding the older age sub-groups’ needs and their interpretations of successful ageing. Research should further explore additional components necessary for successful ageing considering the diversity/heterogeneity of the group of older adults by considering age groups, health, disability status and intersectionality aspects, such as gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, sexual orientation, cultural indicators, education and values, as they contribute to the views of successful ageing. Furthermore, future research and policies related to successful ageing should acknowledge and reflect upon structural components such as the role of environments, access and opportunities for health care, nutrition and social policies that help or hinder the ability to age successfully. Within the context of feminisation of older age, it is well known that women have a higher life expectancy than men (Austad, Reference Austad2006; Glei and Horiuchi, Reference Glei and Horiuchi2007; Zarulli et al., Reference Zarulli, Barthold Jones, Oksuzyan, Lindahl-Jacobsen, Christensen and Vaupel2018). However, most of the participants in the reviewed studies were male, which could provide a somewhat unbalanced gender view of successful ageing by underrepresenting, an otherwise dominant cohort in older age. Therefore, we recommend that future research should reflect the perspectives of successful ageing of a feminised older adulthood. The relatively small number of studies on the perspectives of successful ageing among those 75 and older is an indication that more research is needed in this direction.

Understanding the processes by which older adults adapt, cope and maintain wellbeing in the presence of limitations could inform public health and clinical interventions. Policy makers should cater for the diverse needs of different generations of older populations, young-old (age 65–74), middle-old (75–85) and old-old (85+), and gender differences in order to promote, facilitate and implement suitable policies such as adequate housing, health and social care, and community services that foster individual capacities and willingness to participate in specific tailored programmes.

Due to rapid societal changes propelled by technology, migration and globalisation, pandemics and life expectancy developments, the future of successful ageing might look different for coming generations of older adults, who could benefit from emerging technological and medical advances that aim to facilitate and prolong life (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kelly, Kahana, Kahana, Willcox, Willcox and Poon2015; Martinson and Berridge, Reference Martinson and Berridge2015). Moreover, the lessons learned from the current COVID-19 pandemic could shape our understanding of successful ageing and, more importantly, raise the question whether in times of rapid changes a normative model of successful ageing is still a valid option, especially when such a model could be exclusionary by default.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001070

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Medical School librarians who assisted us with the development of the search strategies for the electronic databases.

Financial support

This work was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement number 754285). The financial sponsor played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data or the writing of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.