Populism is on the rise. In the past decade, this has led to an unprecedented surge in academic interest. Political scientists have produced various comparative studies of populist movements, economists and sociologists have focused on explaining its sudden uptake, and the various disciplines concerned with language and communication have studied populist forms of agitation.

However, on a conceptual level, populism remains an elusive and contested concept. Theorists continue to be at loggerheads about the genus of populism: Some have argued that populism is best understood as a political communication style (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007), a specific form of political mass mobilization (Jansen Reference Jansen2011), or a strategy to gain or maintain political power (Barr Reference Barr2009). Others have argued that populism is best conceived of as a political style (Moffitt and Tormey Reference Moffitt and Tormey2014), a specific discourse (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; Laclau Reference Laclau2018) or an ideology (Mudde Reference Mudde, Kaltwasser, Gardner-McTaggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 29). Even though familiar locutions such as “he is a populist” or “that is a populist party” may suggest that populism is a political ideology, there are good reasons to doubt this. Theorists object to the claim that populism is an ideology on the grounds that it lacks “ideological coherence” (Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2016: 89). In support of this verdict, critics rightly point to the fact that populist movements neither share a grand narrative nor do they draw inspiration from shared political icons or foundational textual sources.

In an attempt to resolve the genus problem, the article develops the following argument to make the case that populism can be fruitfully conceived of as an ideology:

(1) Populists share an ideology I, iff the paradigmatic beliefs and dispositions exhibited by exponents of populism can to a significant extent be explained in terms of the foundational principles which constitute I.

(2) A set of four principles can successfully explain a significant number of paradigmatic beliefs and dispositions exhibited by exponents of populism.

(C) Populists share an ideology that consists of four principles.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 1 introduces explication as a method for reconstructing contested concepts and explicates the concept of ideology. The argument that populism is an ideology that rests on four principles has two parts. Section 2 develops the four principles in turn by drawing on a wealth of empirical studies. Section 3 demonstrates, via deduction, that the identified principles can successfully explain a significant number of paradigmatic populist beliefs and dispositions. Section 4.1 puts together the main argument of the article and concludes that populism is an ideology. Section 4.2 inquires whether the developed account of populism is unique in its explanatory capacity. Section 4.3 attends to a number of open questions.

1. On reconstructing contested concepts

What methods are there to productively engage with contested concepts such as populism? One of the main methods on offer is “conceptual analysis.” This method aims to make explicit an expression (e.g., populism) which is already in use by stating necessary and sufficient conditions for its use or application. However, in order to successfully engage in a project of conceptual analysis, two conditions need to hold: The application of the target concept to be illuminated needs to be (a) “well-determined for every user of the language” and (b) “the same for all users during the time under consideration” (Hempel Reference Hempel1964: 10). Evidently, neither of these conditions hold for the concept under consideration, partly because “populism” is a contested concept. An alternative and ultimately more appropriate method for theorists to engage with contested concepts is the method of “explication” initially developed by Rudolf Carnap.Footnote 1 The method of explication is best conceived of as “a method of re-engineering concepts with the aim of advancing theory” (Brun Reference Brun2016: 1211). In the process of explication, “a concept is replaced by an explicitly characterized ‘new’ concept which can be used in place of the ‘old’ concept in relevant contexts but proves advantageous in [some] respects […]” (Brun Reference Brun2016: 1211). In Carnap's classic account of explication, these advantages are identified as exactness, fruitfulness, and simplicity, whereas recent accounts of explication have emphasized that fruitfulness includes a number of aspects such as explanatory power, usefulness for formulating general laws/regularities, etc. One of the crucial differences between both methods is the success criterion. A conceptual analysis is successful if and only if the definition provided by a conceptual analysis is not open to counterexamples. Explication on the other hand is all about comparative advantages in terms of theoretical values such as simplicity, precision, explanatory power, and so. The method of explication thus does not necessarily feature a single correct answer and counterexamples do not invariably establish defeat.Footnote 2

The goal of this article is to provide a novel explication of populism and defend it on the grounds of its explanatory power, precision, and simplicity.Footnote 3 To be specific, the paper aims to explicate “populism” as an ideology that rests on four principles.

The explication of a target concept, as Brun (Reference Brun2016: 1236) notes, is usually embedded in a “comprehensive process that deals not with replacing individual concepts but with developing systems of concepts.” This also holds true for the current project. In order to develop the proposed account of populism, the concept of ideology, which answers the genus question, needs to be explicated first. For the purposes of the current project, I want to distinguish between political ideologies as abstract-codified sets of principles on the one hand and the political belief systems of actual people on the other. On the present account, political ideologies are understood as ideal types; they are the maximally coherent counterparts to the actual, frequently patchy belief systems of groups of people. In order to illuminate the relation between ideologies and belief systems in more detail, an analogy to language might prove useful: The speakers of any particular language are usually not aware of the fundamental rules of grammar that (imperfectly) govern their language use. Native speakers of a particular language are frequently unable to spell out even the most fundamental rules of grammar, in part because they lack the concepts to do so. Reconstructing the grammar of a language is hence a reconstructive business undertaken by specialists. The same is true for political ideologies. “Native speakers” of a particular ideology are frequently unable to spell out the most fundamental principles of the ideology that governs their political attitudes. Reconstructing the principles that (imperfectly) govern the political attitudes is in turn a reconstructive business undertaken by specialists.Footnote 4

This characterization of ideologies already provides the conditions under which a group of agents can be said to share an ideology: A political group G shares an ideology I, if the political attitudes exhibited by exponents of G are governed by a number of foundational principles which constitute I. This first description, however, is in need of two clarifications: What exactly is meant here by a “political attitude” and how do we ascertain that the political attitudes of the members of a target group are “governed” by a set of shared principles?

The concept of a political attitude is meant to capture the surface-level political beliefs and politically relevant dispositions of an agent. These dispositions might include the tendency of an agent to employ certain heuristics, argumentative schemas, and political strategies, or to exhibit certain recognizable forms of behavior. As for the second question: The political attitudes of the members of group G are governed by a set of principles if those principles are able to explain the political attitudes of the members of group G.Footnote 5 In order to explain a political attitude, the proposed set of principles needs to stand in a logical support relation to the political attitudes in question. In chapter 3, I will have to say more on the issue and walk through a detailed example. With these clarifications on board, we can restate more precisely under which conditions a political group can be said to share a political ideology: A political group G shares an ideology I, if f the paradigmatic beliefs and dispositions exhibited by exponents of G can be explained in terms of the foundational principles which constitute I.

2. Reconstructing populism

In his seminal paper “The Populist Zeitgeist,” Cas Mudde introduced the ideational account of populism by contrasting it with the “Stammtisch” (or pub) interpretation of populism. The Stammtisch account views populism as “a highly emotional and simplistic discourse that is directed at the ‘gut feelings’ of the people” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 542). According to this interpretation “(p)opulists aim to crush the Gordian knots of modern politics with the sword of alleged simple solutions” (Bergsdorff quoted in: Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 542). While Mudde (Reference Mudde2004: 542) acknowledges that this interpretation “has instinctive value,” he rejects it out of hand on the grounds that it is hard to operationalize for the purposes of empirical studies. Contrary to Mudde, I believe that the Stammtisch account provides the keystone for developing a satisfying account of populist ideology.

The argument that populism is an ideology that rests on four fundamental principles has two parts. In this section, I will develop the four principles by drawing on a wealth of empirical studies. The next section demonstrates that the identified principles can successfully explain a significant number of paradigmatic populist beliefs and dispositions. It thus reveals that the identified principles are necessary for explaining paradigmatic populist attitudes. For reasons of readability, I will list the principles here:

1. Common good objectivism: There exists an objective common good and a truth about which public policies are conducive to it.

2. Epistemic optimism: Ordinary people are endowed with a commonsense capacity that permits them to reliably discern the truth of political statements, in particular those that affect the common good, because the truth of political statements is self-evident.

3. Moral optimism: Ordinary people have a capacity for a sense of justice, that is, an effective desire to pursue the common good.

4. Corruption theory of disagreement: Persistent political disagreement exists because of the epistemic or moral corruption of the elite.

One of the key characteristics of populism on the present account, as might be apparent from the descriptions of the principles, is its peculiar epistemic stance. For this reason, it might be called “the epistemic account of populism.” I will proceed by developing the four principles in turn.

2.1. Common good objectivism

On the epistemic account, populism is married to the idea that there exists a common good in some objective sense. In political philosophy, common good conceptions usually identify a privileged, shared set of abstract interests. They are abstract in the sense that the content of the interests is usually spelled out in terms of values rather than in terms of concrete objects. In the literature, we find, for instance, “the interest in bodily security and property,” “the interest in living a responsible and industrious private life,” “the interest in a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties” (Hussain Reference Hussain and Zalta2018), and so on. Within the realm of political ideology, it is a common practice to assume shared interests that are not (directly) refutable by empirical evidence. On most common good accounts, the identified common interests have an objectivist quality, in the sense that they are not open to methods of empirical testing and falsification. Populist ideology shares that feature with other common good accounts. What is particular to populist ideology is, perhaps, that it does not offer a detailed or indeed any description of the content of the common good. However, populist ideology does offer a “method” for establishing the content of the common good. Populists hold that common sense judgments are a reliable way to establish the common good. More on that shortly. The populist conception of the common good can be then characterized in the following way:

Common good objectivism

• There exists an objective common good and hence a truth about which public policies are conducive to it.

Not everybody agrees, however, that populist ideology is tied to some form of objectivism. Waisbord (Reference Waisbord2018: 9) for instance holds that “[p]opulism rejects the possibility of truth as a common normative horizon and collective endeavour in democratic life” (ibid.). He argues that for populists, “‘the people’ and ‘the elites’ hold their own versions of truth.” The question then becomes whether populist ideology subscribes to a form of (moral) objectivism or relativism. The problem with ascribing moral relativism to populists is that it comes with a considerable cost. For instance, if populists subscribe to moral relativism, it is hard to make sense of the populist's claim that the elite is corrupt. The very notion of a corrupted elite seems to imply that there is a shared moral framework from which the elite is deviating wrongfully. If the elite, as Waisbord suggests, is its own group with its own (moral) truth, then in a strict sense it would be irrational to vilify the elite or attribute malignancy to it. Indeed, all the political maneuvers that populists undertake “to safeguard the vision that truth is always on one side” (ibid.: 10) make sense only if a common moral framework is assumed, since relativism is the view that moral truth can and frequently is on both sides. Waisbord then seems to mix up the epistemic and the ontological level of analysis here. He is right that populists reject the liberal view of democracy as a common truth-seeking endeavor. However, as I will argue shortly, the reason is not that populists do not believe in a shared truth, but rather that they reject the epistemic framework that underwrites the liberal version of democracy. The liberal version of democracy is built on the epistemic assumption that truth is hard to come by and that collective truth-tracking requires epistemic humility, inclusive deliberation, trial-and-error, and so forth.Footnote 6 Populists, on the contrary, are committed to epistemic optimism, a view that ascribes Herculean epistemic capacities to ordinary people.

2.2. Epistemic optimism

One of the main goals of this essay is to argue that the appeal to common sense is not just a contingent, but the characteristic feature of populist ideology. Leaving out the epistemological commitment of populism makes populist ideology incoherent and, hence, to some degree unintelligible. Epistemic optimism can be characterized, on a first go, as the view that ordinary people have a specific faculty – common sense – that permits them to reliably discern the truth of political statements and the validity of arguments. Epistemic optimism relies on a specific view about the truth value of propositions. The idea is that the truth of political statement is self-evident, and that common sense is a specific capacity that – if functioning properly – allows ordinary people to discern the truth of political statements and the validity of arguments. To put it in the words of Karl Popper (Reference Popper2014), who introduced the concept of epistemic optimism in Conjectures and Refutations, populism seems to be committed to the view that the truth or rightness of political statements is “manifest.” The claim that the truth is manifest means in the present context that propositions wear their truth value on their sleeves, such that common people “have the power to see it, to distinguish it from falsehood, and to know that it is truth” (Popper Reference Popper2014: 7). The twin ideas of common sense and the self-evidence of true propositions do not entail that people have a priori knowledge of all politically relevant truths. It does not mean that people by themselves can come up with the right policy solutions to political problems. The twin view just proposes that if and when ordinary people are confronted with political statements or arguments, they have the capacity to discern whether they are correct or not. This is an important qualification. If the common sense capacity would allow ordinary people to come up with correct policy solutions on the spot, we could no longer explain why populist movements sometimes defer to experts (of their own liking) and are known to establish counter-institutions tasked with producing whole bodies of “counterknowledge” (Ylä-Anttila Reference Ylä-Anttila2018). Epistemic optimism thus only entails that ordinary people have a capacity to reliably judge the truth of claims issued by experts. Epistemic optimism does not entail the claim that ordinary people are particularly well positioned to come up with the relevant political truths on their own.

An important question is how to best characterize the scope of epistemic optimism. Minimal epistemic optimism is the view that the rightness of some political propositions is manifest to common sense. The issue with the minimal version is not so much that various respectable political doctrines subscribe to the view that some moral or political claims are self-evident. The problem is that the minimal version is incompatible with the stock examples – the manifestation – of populism as described in the third section. If only a few propositions are self-evident, we can no longer make sense of populism's rejection of the institutions of liberal democracy. This suggests that populist ideology is committed to a strong version of epistemic optimism:

Epistemic optimism

• Ordinary people are endowed with a commonsense capacity that permits them to reliably discern the truth of political statements, in particular those that affect the common good, because the truth of political statements is self-evident.

When Mudde introduced the ideational account in 2004, there was not much research on the epistemic dimension of populism. This has changed in the recent years. There is now a growing literature on “epistemological populism” (Saurette and Gunster Reference Saurette and Gunster2011). This literature, however, is less concerned with giving an overarching account of populism, but more so with carving out the epistemic dimension of specific populist movements across countries (Saurette and Gunster Reference Saurette and Gunster2011; Waisbord Reference Waisbord2018; Wodak Reference Wodak2015; Ylä-Anttila Reference Ylä-Anttila2018). In the following section, I will draw on this literature and various other bodies of research on populism to substantiate the claim that epistemic optimism is not only a contingent feature but a defining element of populist ideology. Let me start off then with two paradigmatic examples. The first example, often cited in literature on populism, is a quote by the right-wing Prime Minister of Hungary, Victor Orbán:

No policy-specific debates are needed now, the alternatives in front of us are obvious […] I am sure you have seen what happens when a tree falls over a road and many people gather around it. Here you always have two kinds of people. Those who have great ideas about how to remove the tree. […] Others realize that the best is to start pulling the tree from the road. … [W]e need to understand that for rebuilding the economy it is not theories that are needed but […] thirty robust lads who start working and implement what we all know needs to be done. (Quoted in: Enyedi Reference Enyedi, Kriesi and Pappas2015: 233–4, emphasis added)

What I want to draw attention to here is that Orbán claims that what needs to be done to build the economy is self-evident. Hence, any debate about restoring the economy is nothing more than a waste of time. As Enyedi explains, this statement by Orbán was issued in response to the question why he refused to partake in election debates. Another paradigmatic example is the following statement by the forty-fifth president of the United States, Donald Trump:

On every major issue affecting this country, the people are right and the governing elite are wrong. The elites are wrong on taxes, on the size of government, on trade, on immigration, on foreign policy. (Quoted in: Oliver and Rahn Reference Oliver and Rahn2016: 189)

One might ask, how can it be that the people are right on such complex and often technical questions such as taxes, trade, immigration, and foreign policy, whereas the experts – that is people who have spent their life on studying these questions – are so reliably unreliable? Note that the answer cannot lie in the moral quality of the people as Mudde's account (cf. Section 4) suggests. Having a deep understanding of virtue does not answer any of these questions.

Lending further credence to the case, various scholars studying populism provide expert testimony that populists are committed to epistemic optimism. For instance, the political scientist Yascha Mounk (Reference Mounk2018: 7) writes in his recent The People vs. Democracy that populists believe “that the great mass of ordinary people instinctively knows what to do” and that the “major political problems of the day […] can easily be solved” by “common sense” (Mounk Reference Mounk2018: 41). Recounting his view on populism in seven theses, Müller (Reference Müller2017: 101) notes that populists “insist that the elites are immoral, whereas the people are a moral, homogenous entity whose will cannot err.”Footnote 7 It also bears emphasis that epistemic optimism connects well to the claim that populism is “a politics of hope,[…] the hope that where established parties and elites have failed, ordinary folks, common sense, and the politicians who give them a voice can find solutions” (Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and van Droogenbroeck2016: 336).

Besides paradigmatic examples and expert testimony, there is also a growing number of qualitative and quantitative studies to bolster the case. In their landmark study, Paul Saurette and Shane Gunster (Reference Saurette and Gunster2011) examined the rhetorical strategies of Adler On Line (AOL), a pre-eminent, right-wing populist radio program in Canada. Their study (Reference Saurette and Gunster2011: 196) shows that “the program's rhetorical practices establish a specific epistemological framework” that the authors call “epistemological populism.” The epistemological framework, on which the show operates, valorizes “the knowledge of ‘the common people’” (199) and “employs a variety of populist rhetorical tropes to define certain types of individual experience as the only ground of valid and politically relevant knowledge” (196). Moreover, the authors argue “that this epistemology has significant political impacts insofar as its epistemic inclusions and exclusions make certain political positions appear self-evident and others incomprehensible and repugnant” (196). The framework employed is built on the premise that common people possess a particular reliable knowledge “by virtue of their proximity to everyday life, as distinguished from the rarefied knowledge of elites which reflects their alienation from everyday life (and the common sense it produces)” (199). What is important is that the framework does not only “elevate individual experience,” it also extends the “epistemological authority well beyond the realm where the person's immediate experience itself might be seen as relevant” (202). One way to make sense of epistemic optimism is then that it relies on the background assumption that the proximity to everyday life cultivates the common sense of ordinary people to such a degree that it allows them to reliably judge the truth of political statements and claims. On the basis of this exposition, it becomes intelligible then that the “appeal to ‘common sense’” on AOL serves as “a discussion-ending trump card” (199).

Ruth Wodak (Reference Wodak2015: 166), studying right-wing populism, comes to similar conclusions. Right-wing populism, she argues, is an expression of the “arrogance of ignorance.” Analyzing the rhetoric of the so-called “Mama Grizzlies” alliance, led by former governor of Alaska Sarah Palin, Wodak writes: “The ‘Mama Grizzly’ coalition emphasizes ‘kitchen table economics’, that is, the position that the state budget should be run like the family budget. As women are daily involved in caring for their families and living costs, they should know – by common sense and experience – how to run the state” (186).

Apart from qualitative studies, a new line of quantitative research has produced new insights about populist belief sets. What is interesting for the present purposes is that this line of research confirms that there is high agreement among populists on a number of epistemically charged statements such as:

• “The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions” (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014).

• “Elected officials talk too much and take too little action” (ibid.).

• “Those who have studied for a long time have lots of diplomas, but they do not know how the world really works” (Elchardus and Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2012 quoted in: Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014).

• “Important questions should not be decided by parliament, but by referendum” (Vehrkamp and Merkel Reference Vehrkamp and Merkel2019, my translation).

• “The citizens of Germany in principle agree about what political actions need to happen” (ibid.).

The responses to these questionnaires can be interpreted in various ways. Undoubtedly however, one plausible reading is an epistemic one: Important policy questions should be left to the people because they know better; diplomas and other academic achievements just lead to confusion; and common sense on the other hand leads to broad agreement on what needs to be done.

In the end, the question of whether the principle of epistemic optimism belongs to the foundational principles of populist ideology is a conceptual one and thus cannot be answered by empirical evidence alone. Nevertheless, the mounting empirical evidence suggests that epistemic optimism might very well be a constitutive part of populist ideology.

2.3. Moral optimism

That ordinary people are capable to discern the common good does not mean that they are motivated to pursue it in the public realm. For every agent, it is rational to pursue the common good only insofar as it benefits him. It is reasonable to assume that almost every individual has an interest in policies that secure prosperity, security, peace, and so forth. However, every individual also has a set of private interests – say, special protections for the industry he is working in, subsidies for his favorite pastime activity, and so on. Thus, every individual, from a purely rational point of view, has a reason to use public policy not only to further the common good, but also his private good to the detriment of others. Hence, for politics to be a pure expression of the common good, it is not sufficient that people know the correct articulation of the common good – they also need to be motivated to pursue the common good, exclusively. Populist ideology, on the present reconstruction, is sensitive to this issue and ascribes a moral capacity for a sense of justice to ordinary people. The term “sense of justice” should be understood here along Rawlsian lines, that is, as a “normally effective desire to comply with duties and obligations required by justice” (Freeman Reference Freeman and Zalta2019) or the common good. The allusion to Rawls is meant to emphasize the point that ascribing an effective desire to comply with the demands of justice is a feature that is common in political theories and thus not a feature that is in any sense unique to populist ideology.

The ideational account by Cas Mudde characterizes the people as being morally pure. This might strike one as odd and potentially misleading. Do populists really conceive of the people as morally pure? Isn't it the case that populist politicians use vile language, mock “do-gooders” and norms of “political correctness” all the time in an attempt to connect with the “people”? On the face of it therefore, it does not seem right that populists view ordinary people as “pure” or as particularly “moral” in any conventional sense. I want to suggest, then, that we should understand the ascription of “morality” to ordinary people in a more minimal sense. Populist ideology, I suggest, ascribes to the people a sense of justice: an effective desire to pursue the common interest and only the common interest in the political arena. The third principle can thus be put like this:

Moral optimism

• Ordinary people have a capacity for a sense of justice, that is an effective desire to pursue the common good.

The pursuit of the common good finds its expression in the general will. Before we move on, let me add a clarificatory note. One might wonder what the point is of reconstructing populist ideology in such “philosophical” detail. Is this really necessary? After all, populists never talk in those terms! The answer to that is that the identified principles are necessary for explaining paradigmatic populist attitudes. If we drop, say, the principle of moral optimism, we can no longer explain the target set of populist beliefs and dispositions described in Section 3.

Next, I will discuss, how on a populist epistemology persistent disagreement can be explained.

2.4. Corruption theory of disagreement

Assume that populist epistemology is correct, assume that ordinary people have the capacity to discern true political propositions from false ones with ease. If this is correct, it suggests that once somebody in society has discovered the correct articulation of the common good, this knowledge should immediately become public in the age of digitalization. Metaphorically speaking, on a populist epistemology, correct information about the content of the common good and correct information about the right public policies should spread like a highly contagious virus.

What do populists then make of the fact that political disagreement is so persistent? With persistent political disagreement, I simply mean any political disagreement that survives sustained deliberation. Given that ordinary people have the capacity to recognize the truth, it initially seems hard to explain such disagreement. We might be able to explain episodic disagreement. For instance, one might imagine that Bettina believes that policy Z is approximately right. Bettina cannot believe that Z is right, because if it were right, she would know. But, since she does not know what the right policy is, she holds that something approximating Z must be right. Now, assume that Linnea knows that policy A is correct. Formally, we might want to say that there is a disagreement between Linnea and Bettina. However, on a populist epistemology, such disagreements can hardly be stable, since all it would take for Linnea to convince Bettina is to explain policy A. After all, the rightness of the proposal is manifest. Hence, under normal circumstances, mere ignorance cannot explain persistent disagreement. How can we then, on a populist epistemology, explain persistent political disagreement?

Notice that on the standard epistemology underlying liberal philosophy, disagreement about facts and norms is taken to be the “normal result of the exercise of human reason” (Rawls Reference Rawls2005: 16) due to the burdens of judgment. On standard accounts of epistemology, what needs to be explained is knowledge, not ignorance. On a populist epistemology, things are different. Within the logic of populist ideology, there are only two ways to explain persistent political disagreement: moral or epistemic corruption. An agent can be said to be morally corrupted if she feigns disagreement for ulterior motives and thus argues for a position against her better knowledge. An agent is epistemically corrupt if she simply cannot see the truth even if she is presented with it.Footnote 8 Hence on a populist ideology, there is no reasonable disagreement. The fourth tenet can be then put like this:

Corruption theory of disagreement Footnote 9

• Persistent political disagreement exists because of the epistemic or moral corruption of the elite.

The populist explanation of disagreement resembles certain versions of socialist epistemology that chalk up disagreement to false consciousness, and various religious denominations that are not shy to play the devil card when reasonable discussions threaten to get out of hand (Popper Reference Popper2014: 9). The populist explanation of disagreement seems to be systematically similar in that it must deny a sincerely disagreeing party the status of cognitive peerhood. However, the populist has a specific explanation for why sometimes huge parts of society disagree with him: elite conspiracies that work toward corrupting the moral and epistemic capacities of ordinary people (Bergmann Reference Bergmann2018; Mounk Reference Mounk2018).

If populists are logically committed to the corruption theory of disagreement, this should surface in how populists react to political disagreement. If the fourth tenet is a constitutive part of populist ideology, we would expect that populists chalk up dissenting voices in the media, by experts, or politicians to the latter being corrupted. And certainly, this is what populists do. One of the most prominent figureheads of the Italian populist party MoVimento 5 Stelle, Luigi di Maio, had this to say about the Italian media on his Facebook account: “The true plague of this country is the majority of the media, intellectually and morally corrupt, which is waging war against the government, trying to make it fall” (Lusi Reference Lusi2018). Of course, former US President Donald Trump is also known for his contempt of the media. To cite just one out of many similar Twitter outbursts (emphasis i.o.): “The Corrupt News Media is totally out of control – they have given up and don't even care anymore. Mainstream Media has ZERO CREDIBILITY – TOTAL LOSERS!” More examples can be found in Brandmayr's research on the Italian populist Alberto Bagnai. Bagnai, himself an economist by training, frequently calls economics correspondents working for mainstream media outlets “hired guns,” “regime's misinformators,” and “regime's clowns,” high-profile economists that disagree with him don't fare better and get ridiculed as “organic intellectuals of the capitalist class” (Brandmayr Reference Brandmayr2021). Even though research of populism generally acknowledges populist's disdain of the media, only few have commented explicitly on the logical relation between populist's commitment to epistemic optimism and their frequent accusations of corruption. One exception is Mounk (Reference Mounk2018: 39) who explains, “if the solutions to the world's problems are as obvious as [the populists] claim, then political elites must be failing to implement them for one of two reasons: either they are corrupt, or they are secretly working on behalf of outside interests.”

3. The explanatory power of the epistemic account of populism

The argument that populism can be reconstructed in terms of a number of principles has two parts. In the last section, I began to lay out the case for the claim that populism can be explained in terms of the four principles enshrined in the epistemic account of populism. This section strengthens the case by demonstrating that the identified principles can successfully explain a wide range of characteristics that are generally associated with contemporary populism.

To that end, I demonstrate that the definition of populism provided is consistent with a number of characteristics frequently attributed to populists. This means, roughly, that there is no contradiction in accepting the four principles of populism and acting, behaving and speaking like populists usually do. Thus, an agent who subscribes to the four principles is able to act and speak like a populist without cognitive dissonance.

However, I wish to defend a stronger claim. The novel definition of populism is not only consistent, but coherent with how populists usually act, behave, and speak. This means that the principles enshrined in the definition of populism explain (from an external) and thus justify (from an internal point of view) a wide range of attitudes typically associated with populism. Hence, if an agent adopts the four principles as commitments, it becomes rational for him to hold the beliefs and engage in the behaviors that are commonly associated with populism.

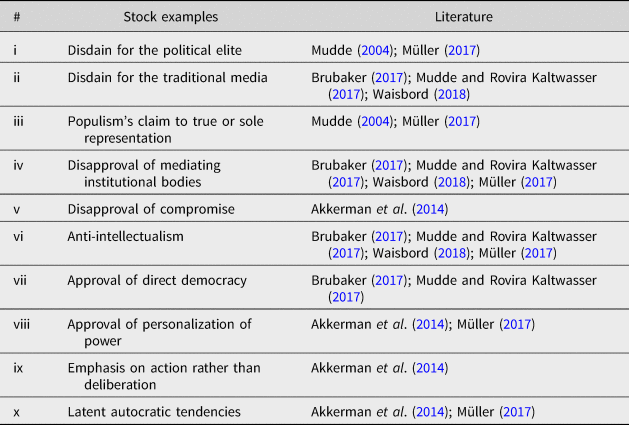

The goal of this section is to demonstrate that the four principles identified in the last section are able to explain a number of paradigmatic populist beliefs and dispositions. For that purpose, ten paradigmatic examples frequently cited in the academic literature on both left- and right-wing populism were selected. These “stock examples” – as shown in the right column – are also frequently cited by advocates of the influential ideational approach to populism. The list of stock examples can be thought of as the “manifestation of populism” (Table 1).

Table 1. Manifestation of populism

One might wonder what the relation in terms of size is between the set of all people (ALL) that have been labeled “populist” in contemporary debates and the set of people (P) whose attitudes are well described by these ten characteristics. For the purposes of this article, I can remain agnostic about what the exact relation between these groups is as long as P represents some relevant subset of ALL. That P is a relevant subset of ALL in turn is an assumption that I take to be well justified on the grounds that the identified features figure prominently in the description of populist attitudes across the academic literature. The principles of populism developed in this article are then meant to explain belief systems that approximate P.Footnote 10

In what follows, I will sketch how to deductively derive these ten items as conclusions by utilizing the identified principles and a number of auxiliary hypotheses. The first premise is implied by the first (common good objectivism) and the third principle (epistemic optimism). The second premise reflects the second principle (moral optimism).

1. If the political elite is uncorrupted and minimally informed, then it knows the correct set of policies P to solve social problem S.

2. If the political elite knows the correct policies and is benevolent, then it will enact the right policies P to solve social problems S.

3. The right policies were not enacted.

From this it follows:

4. The political elite is either ignorant, morally or epistemically corrupted (from 1 to 3).

5. The elite is minimally informed ( = not ignorant).

From these points, the first major conclusion can be derived:

6. The elite is either morally or epistemically corrupted (from 4, 5).

This line of reasoning establishes then item (i), populists' disdain for the elite. In a similar fashion we can derive item (ii), i.e., the view that much of the media is either morally or epistemically corrupted.

7. If a collective agent knows the correct policy and it is benevolent, then it will propose the right policies P to solve social problems S.

8. The media does not propose the right policies.

9. Thus, the media is either ignorant or morally or epistemically corrupted (from 1, 7–8).

10. The media is minimally informed ( = not ignorant).

From these premises, we can then derive our next important conclusion:

11. The media is either morally or epistemically corrupted (from 9 to 10).

Next, we want to derive the corruption theory of disagreement from the first premise.Footnote 11

12. If the truth regarding public policy is manifest, then there can be no reasonable disagreement about public policy.

The content of corruption theory of disagreement follows straightforwardly:

13. There can be no reasonable disagreement about public policy (from 1, 12).

In the next step, we will see that items (iii)–(viii) from the list of stock examples can be derived in a similar fashion.

14. Only if there is reasonable disagreement, (iii) then a plurality of reasonable factions must be represented in parliament and (iv) then there is a moral justification for mediating institutions that (v) facilitate compromise. Only if the antecedent is true, then there is sufficient epistemic value in deliberation to justify parliamentary forms of democracy and then there is epistemically something to be gained by (vi) experts, intellectuals, and journalists debating policy issues in the media.

Since populists by virtue of affirming the corruption theory of disagreement deny that reasonable disagreement exists, it follows:

15. Thus, there is no need for (iii) plural representation and (iv) there is no need for mediating institutions that (v) facilitate compromise. Moreover, there is nothing to be gained epistemically (vi) from parliamentary forms of democracy, or (vi) experts, intellectuals, and journalists debating policy issues in the media (from 13 and 14).

Moreover, if there is – as populists believe – no epistemic value in inclusive deliberation, all it takes to move us to a more just world is identifying the common good by (vii) direct democratic means and a (viii) strong leader who puts into action what we all already know needs to be done. If what needs to be done is manifest, then political leaders should emphasize action over deliberation (ix). Finally, we can also explain why populists have a tendency toward authoritarianism when in office.

16. A populist leader is minimally informed, uncorrupted, and benevolent.

17. Thus, if a populist leader is in power, he will enact the right kind of policy (from 1, 2, 16).

18. If the right policies are enacted and the social problems persist over time, then the policies were sabotaged by the corrupted.Footnote 12

19. If policies are persistently sabotaged by the corrupted, then employing autocratic means is justified.

20. The populist leader is in power and the social problems persist.

21. Thus, employing autocratic means against the corrupted and malignant is justified (from 16 to 20).

The last argument is supposed to capture the following thought. On a standard fallibilistic epistemology, if a policy does not show the desired effects, then this prima facie counts against the efficacy of the socio-economic policy and, perhaps, even against the theory from which the policy was derived. On the contrary, on a populist epistemology, the efficacy of policy cannot be doubted since its rightness is self-evident or manifest. Hence, populist policies can only fail because of nefarious influences by third parties. It should be further noted that these are not the only features of populism that can be derived in a similar fashion. For instance, it has often been pointed out that populists are prone to invoke conspiracy theories (Bergmann Reference Bergmann2018; Mounk Reference Mounk2018; Müller Reference Müller2017). This feature can be accounted for on the epistemic account, since persistent political disagreement within the populist political epistemology can only be explained by conspiracies. On a populist epistemology, there is virtually no other way to explain persistent political disagreement.

The sketched deduction represents a genuine explanation of populist attitudes. Every major conclusion (i–x) logically depends on the first premise. From a political theory point of view, the identified four principles explain the beliefs and dispositions of populist agents. On the flip side, from the internal standpoint of the individual populist, the same principles can be drawn upon for purposes of justification.

4. What is the genus of “populism”?

This final section has three parts: In Section 4.1, I will put together the components developed in the past sections to finalize the case for the claim that populism can be fruitfully conceived of as an ideology. Section 4.2 takes up the question of whether rival accounts can equally well explain the stock examples in terms of a number of principles. Section 4.3 concludes the article by attending to a number of open questions concerning the epistemic account of populism.

4.1. The genus of populism

Should populism be understood as an ideology or rather, say, as a certain mode of communication or stylistic repertoire? Aslanidis (Reference Aslanidis2016: 89) puts the challenge to the advocates of the ideology clause like this: “The staunchest proponents of the ideological clause […] implicitly or explicitly acknowledge that it basically lacks what Gerring (Reference Gerring1997) has distilled as the single most unchallenged dimension of ideology in the literature: coherence.” I do not want to comment here on whether the proponents of other accounts (wrongly) hold that populism lacks coherence. In the past three sections, I have slowly built up the core components for the argument that populism is best conceived of as an ideology. The first section developed the claim that:

(1) Populists share an ideology I, iff the paradigmatic beliefs and dispositions exhibited by exponents of populism can to a significant extent be explained in terms of the foundational principles which constitute I.

The second and the third section developed the main claim of the paper:

(2) Four principles can successfully explain a significant number of paradigmatic beliefs and dispositions exhibited by exponents of populism.

This section then draws the conclusion from the constructed syllogism:

(C) Populists share an ideology that consists of four principles.

This concludes the main argument of this article. I have argued, employing the method of explication, that populism is an ideology resting on four specific principles. These principles both explain (from an external) and justify (from an internal point of view) the attitudes of populist agents. From the reconstruction undertaken in the paper, populism henceforth emerges as a highly coherent ideology. A central contribution of this paper is hence to put to rest the claim that populism is not an ideology because it lacks coherence.

The reason why theorists have failed to grasp the coherence of populist ideology, I suspect, is that they have looked in the wrong place. Theorists – looking for coherence – have been out hunting for the normative core of populism, a “grand vision” or “comprehensive ideological projects” (Betz Reference Betz1994: 107 cited in Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2016: 89). Coming home empty handed, they have concluded that populism is not a political ideology after all. However, the characteristic feature of populism is not to be found in a specific moral but in its epistemic commitment. Its epistemic commitment also explains why it can do without a normative vision: (almost) everything that is worth knowing about the common good and the right public policies can reasonably be assumed to be part of the common knowledge of the true people.

4.2. Comparative explanatory power

One might wonder whether the epistemic account is unique in its ability to explain the stock examples gathered in Table 1. For reasons of space, I will need to confine myself here to the limited argument that at least the most influential account of populism that defends the ideology clause, the one by Cas Mudde, fails where the epistemic account succeeds.

Mudde (Reference Mudde2004: 543, italics suppressed) defines populism as an “ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.” Mudde's definition consists of a number of concepts. The concepts that Mudde refers to are the notions of ideology, the people, the elite, and the concept of the general will. The first concept on that list answers the genus question of populism while the other three concepts spell out the content of populism. On Mudde's account, the notion of the people is understood as a set of individuals that share a specific moral conception. The people are thus, as Mudde emphasizes, not defined in terms of properties such as ethnicity, nationality, or class, but in terms of a shared moral framework. Hence, according to Mudde (Reference Mudde, Kaltwasser, Gardner-McTaggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 29), morality is the “essence of the populist division.” The elite is defined ex-negativo as a group that does not share the specific moral conception of the people. The division between the people and the elite is thus, again, “based on the concept of morality” (30). The general will, on this account, is simply understood as the natural expression of the shared morality of the people. As Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2009: 1043) explains, the notion of “the popular will” within the populist belief system is best conceived of as “a crude version of Rousseau's General Will.”

The reason why the ideational approach has a hard time explaining the earlier stock examplesFootnote 13 is the following: On a conceptual level, the problem with the ideational account in general and Mudde's account in particular is that agreement over values – i.e., a shared moral code or framework – is logically compatible with pervasive disagreement about questions of how to best achieve those desired values. The ideational account holds that populists are committed to the view that the true people share a “morality” or moral framework. What I want to draw attention to is that an agreement on a moral framework is fully consistent with deep disagreements about public policy matters. In order to translate a moral framework into policy prescriptions, one needs to bring in numerous non-moral background assumptions. These background assumptions might relate to social scientific facts, or scientific questions such as the dynamics of climate change, the infection rates in a pandemic or questions about vaccination. Political disagreements thus frequently come down to instrumental disagreements, i.e., disagreements about how to best reach our shared goals. For that reason, moral homogeneity – a shared moral framework – on its own does not entail a general will in terms of policy preferences.

However, if the general will is purely an expression of the people's moral framework, then the ideational account simply cannot explain the stock examples and hence fails in terms of explanatory power. Why is that the case? If Mudde's account of populist ideology permits instrumental disagreement, then there is no reason to assume that “the people” would agree on questions of public policy. But if the people do not agree on matters of public policy, it becomes unintelligible why populists disapprove of plural representation, compromise, mediating institutions, and so forth. To give a simple example: Assume that “the people” share a concern for the working poor. Now, one subset of the people might believe that the best way to make the working poor better off are minimum wage laws, citing one batch of empirical evidence, while another subset of the people might believe that such laws would only make things worse, citing another batch of evidence. The same goes for all kind of problems such as health insurance, climate change, and so on.

How is this conflict to be solved according to populist ideology? It seems that if populist ideology permits instrumental disagreements, then it becomes unintelligible why populists reject (or at least are highly skeptical with regard to) liberal institutions. And that is where the rub is: the set of institutions that can be defended based on a broadly liberal framework can also be defended on the grounds of a populist ideology that permits instrumental disagreement while subscribing to some form of moral monism.

To sum up then, since the ideational account of populism permits instrumental disagreement, it cannot explain the real-world manifestation of populism.

4.3. Questions and rejoinders

The epistemic account of populism certainly raises a lot of questions and I cannot hope to address all of them. Here are the answers to some of the perhaps most pressing questions:

1) How to make sense of the notions of “the people, the elite, and the general will” within the epistemic account?

The epistemic account retains and clarifies the three mentioned elements as follows: On the epistemic approach, there are two relevant qualities of political agency: the capacity to reliably distinguish truth from falsity – the epistemic capacity, and the standing motivation to be guided by the common good – the moral capacity. The capacities come as binaries, such that the capacities either work or are corrupted. From this description, it follows that populist ideology, in principle, distinguishes between four types of agents. The first type of agent possesses a working epistemic and moral capacity, these are – in Mudde's language – the true people. The true people have the capacity to discern truth from falsity and have a standing motivation to act on what they know to be the correct articulation of the common good. The elite, on this account, is then simply defined by the corruption of at least one of the two capacities. The general will on this account is then simply the homogenous will of epistemically and morally uncorrupted people.

2) How does the epistemic account deal with counterexamples?

Assume a politician that has been labelled “populist” has acted, behaved, or talked in a way that directly contradicts one of the items in the list of stock examples or one of the core principles of the epistemic account. How to deal with counterexamples that take this form?

In general, it should be remembered that not every demand made by a populist should be called populist. Likewise, not every demand made by a racist should be called racist. If a racist publicly advocates a minimum wage, that does not make the demand for a minimum wage racist. Politicians and policy makers are human actors. Human actors rarely argue on the basis of a coherent set of premises. So, we should not be surprised that a politician argues populistically (as defined by the epistemic account) with respect to one subject matter and argues conservatively with respect to another. When we call a politician “populist,” we mean only that this politician argues predominantly in a populist fashion and not that she argues exclusively along populist lines.

Let us assume, however, that there are some political parties and politicians across the globe that have been labeled populist, but their political programs do not fall under the definition of the epistemic account. How to respond? There are two interconnected responses: First, such counterexamples would count as defeaters, if the goal of this paper had been to give a conceptual analysis of “populism.” However, the goal of this paper was not to give a conceptual analysis, but to reconstruct the concept by way of an explication. The second response is then simply to suggest that – at least within the academic discourse – we should refrain to label those politicians and parties “populist,” but find labels that more adequately capture the core of their respective ideologies. If a party runs on a mostly ethno-nationalistic platform, why insist on calling it “populist” rather than, say, “ethno-nationalist”?

3) “Why does it matter whether populism is a bag of rhetorical tricks or an ideology?”

What is the practical upshot of conceptualizing populism as an ideology rather than a bag of rhetorical tricks? This is a complex question to which I can only provide a brief response here.

In contemporary public discourse, “populism” serves as a catch-all label for political platforms or movements that challenge the established political order, drawing on the “elite” versus “people” dichotomy. A salient problem with such a loose conception of populism is that it is overinclusive. As noted by political economist László Andor (Reference Andor2020: 24), even green and liberal parties in developing countries occasionally employ this rhetoric to combat entrenched elite corruption. More concerning, however, is that accounts of populism that emphasize rhetorics obscure important differences between political ideologies. They tend to lump together distinct political platforms – such as left- and right-wing parties – which not only have very different historical roots but also adhere to fundamentally different set of normative and epistemological premises. Rather than providing a more nuanced taxonomy of political movements and ideologies, explicating populism as a rhetorical style risks to level these essential distinctions. Andor encapsulates this concern succinctly: “It has never properly been explained why nationalist, authoritarian, far right and neo-fascist tendencies should not be called nationalist, authoritarian, far-right, or neo-fascist, but populist instead” (Reference Andor2020: 26).

We assign unique labels to distinct objects as a constant reminder of their ontological distinctiveness. This ensures that we deal with them individually and on their own terms. The linguistic implication of the proposal put forward by this essay is to reserve the label “populism” for political movements that fulfill the four conditions specified earlier. This has three important practical advantages. Firstly, it retains the traditional political science distinctions between authoritarianism, nationalism, fascism, and so forth, rather than subsuming them under the term populism. Secondly, it allows us to distinguish between standard variants of nationalist, fascist, or socialist platforms and their distinctly populist counterparts.Footnote 14

However, the most significant practical implication of the epistemic account of populism is that it provides a unique perspective on the compatibility between populism and liberal democracy. According to the epistemic account, populism is fundamentally incompatible with democracy because it denies the possibility of reasonable disagreement about facts and norms.Footnote 15

Modern liberal democratic society is built on the premise that human judgment is fallible and that reasonable disagreement is the “natural outcome of the activities of human reason under enduring free institutions” (Rawls Reference Rawls2005: xxiv). Populism is incompatible with liberal democracy because it is committed to the claim that the truth is manifest and that political disagreement is the result of moral and epistemic corruption. Within the populist framework, there is simply no room for reasonable disagreement: one is either aligned with the truth or tainted by corruption., Footnote 16