Atypical or second-generation antipsychotics are said to differ from conventional or typical antipsychotics in terms of their effects on the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia and on cognition, and in terms of their adverse effect profiles (Reference Gelder, Lopez-Ibor and AndreasonGelder et al, 2000). Aripiprazole is the prototype of a ‘third generation’ of antipsychotics - the so-called dopamine-serotonin-system stabilisers (Reference Rivas-VasquezRivas-Vasquez, 2003). It is claimed to be at least as effective as haloperidol in the treatment of positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and it may cause fewer adverse effects. Aripiprazole is reported to be useful in all phases of schizophrenia, and to enhance cognitive function (Reference Rivas-VasquezRivas-Vasquez, 2003). In 2002 the drug was granted approvable status by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of schizophrenia (Reference Dubitsky, Harris and LaughrenDubitsky et al, 2002). It has been included in recent guidelines on schizophrenia treatment (American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Schizophrenia, 2004) and it is licensed for use in several other countries, including the UK. We here report the findings of a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the effects of aripiprazole.

METHOD

Search strategy

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's register (August 2004) and we also hand-searched relevant journals and conference proceedings, and used several grey literature sources (including pharmaceutical industry materials and non-systematic internet searches). In addition, we inspected the references cited in identified studies for further trials and we examined the FDA website. We also contacted relevant authors and the manufacturers of aripiprazole (Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka pharmaceuticals). Full details have been published previously (Reference El-Sayeh and MorgantiEl-Sayeh & Morganti, 2004).

Selection and inclusion criteria

We reliably selected RCTs that compared aripiprazole at any dose (the recommended target dose is 10-15 mg/day, range 10-30 mg/day) with any other antipsychotics or placebo in the treatment of people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like psychoses. Our primary outcome was relapse, but we also investigated a number of other outcomes, including death, mental state, cognitive functioning, adverse effects and quality of life. Before we viewed the data, we stipulated that outcome measures were to be categorised as short-term (up to 12 weeks), medium-term (13-26 weeks) or long-term (over 26 weeks). We assessed study quality using the criteria described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2.0 (Reference Clarke and OxmanClarke & Oxman, 2003).

Data analysis

We analysed the data using RevMan version 4.2.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK; see http://www.cc-ims.net/RevMan/current.htm), and we calculated random-effects relative risk (RR) and its 95% confidence interval by intention-to-treat analysis. Where possible, we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) and the number needed to harm (NNH) (see http://www.nntonline.net). On the condition that more than 60% of participants were accounted for with respect to any given study outcome, everyone allocated to the intervention was counted, whether they completed the follow-up or not. It was assumed that those individuals who dropped out had a negative outcome (other than death). Continuous data were synthesised using weighted mean difference. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by inspecting the relevant graph and was supplemented using the I-squared statistic (Reference Higgins, Thompson and DeeksHiggins et al, 2003). If inconsistency was high (>75%), the data were not pooled, but were presented separately and the reasons for heterogeneity were investigated.

RESULTS

We identified over 400 citations, of which 54 reported 10 relevant studies (Table 1). All of these 10 studies were randomised, and all but one (Reference Kern, Cornblatt and CarsonKern et al, 2001) were double-blind. However, none of them made the method of randomisation explicit or tested masking. Consequently they all carry a moderate risk of bias and may therefore overestimate the positive effects of aripiprazole (Reference Clarke and OxmanClarke & Oxman, 2003). Six of the studies reported data up to 12 weeks (Carson et al, Reference Carson, Ali and Saha2000, Reference Carson, Pigott and Saha2002; Reference Daniel, Saha and IngenitoDaniel et al, 2000; Reference Adson, Bari and BonaAdson et al, 2002; Reference Kane, Carson and KujawaKane et al, 2003; Reference Potkin, Saha and KujawaPotkin et al, 2003), three reported data up to 6 months (Reference Kern, Cornblatt and CarsonKern et al, 2001; Reference Carson, Pigott and SahaCarson et al, 2002; Reference McQuade, Jody and KujawaMcQuade et al, 2003) and one reported data at 1 year (Reference Kujawa, Saha and IngenitoKujawa et al, 2002).

Table 1 Characteristics of studies included in the review

| Study | Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adson et al (Reference Adson, Bari and Bona2002) | Allocation: randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM–IV) n=420 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 10 mg/day (n=106) | Leaving the study early |

| Blindness: double (in treatment responders) | Age: over 18 years, average c. 41 years | 2. Aripiprazole: dose 15 mg/day (n=106) | Unable to use the following: | |

| Duration: 6 weeks, preceded by > 2-day wash-out period | Gender: male, 327; female, 93 | 3. Aripiprazole: dose 20 mg/day (n=100) | Death: suicide and natural causes (incomplete data) | |

| Design: parallel, multicentre | History: acute relapse, response to previous neuroleptics other than clozapine, out-patient > 3 months in past year, PANSS total score > 60, and > 4 on two defined PANSS criteria | 4. Placebo (n=108) | Mental state: PANSS total score, PANSS-derived BPRS core score, PANSS negative sub-scale (no s.d. data) | |

| Setting: hospital, North America | ||||

| Carson et al (Reference Carson, Ali and Saha2000) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM–IV) n=414 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 15 mg/day (n=102) | Leaving the study early |

| Blindness: double (no further details) | Age: mean c. 39 years | 2. Aripiprazole: dose 30 mg/day (n=102) | Unable to use the following: | |

| Duration: 4 weeks, preceded by > 5-day wash-out period | Gender: male, 288; female, 126 | 3. Haloperidol: dose 10 mg/day (n=104) | Death: suicide and natural causes (incomplete data) | |

| Design: parallel, multicentre | History: acute relapse, mean age at first episode c. 22 years, mean number of previous hospitalisations c. 10 | 4. Placebo (n=106) | Global state: CGI (no s.d. data) | |

| Setting: hospital, USA | Mental state: BPRS, PANSS-derived BPRS score (no s.d. data) | |||

| General functioning: CGI (no s.d.) | ||||

| Adverse effects: SAS, Barnes Akathisia Scale, AIMS, other outcome measures including changes in body weight, serum prolactin levels and QTc interval (no usable/s.d. data) | ||||

| Carson et al (Reference Carson, Pigott and Saha2002) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia n=310 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 15 mg/day (n=155) | Global state: relapse |

| Blindness: double (no further details) | Age: mean c. 42 years | 2. Placebo (n=155) | Adverse effects: adverse events above 10%, weight gain > 7%, fasting plasma glucose ⩽ 110 mg/dl, HbA1c ⩾ upper limit of normal, clinically significant laboratory measurements | |

| Duration: 26 weeks, preceded by 3- to 14-day wash-out period | Gender: male, 174; female, 136 | Leaving the study early | ||

| Design: parallel, multicentre | History: chronic stable, no significant worsening of symptoms in past 3 months, diagnosis for > 2 years, mean baseline PANSS score c. 82 | Unable to use the following: | ||

| Setting: mixed in- and out-patients, multinational | Global state: PANSS, CGI, PANSS-derived BPRS (no s.d. data) | |||

| Adverse effects: change in weight, change in serum prolactin levels, SAS, AIMS, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, change in QTc interval, change in fasting plasma glucose, change in HbA1c from baseline (no usable/s.d. data) | ||||

| Csernansky et al (Reference Csernansky, Garbutt and Goff2002) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM–III–R) n=103 | 1. Aripiprazole (OPC-14597): dose 5 mg on days 1+2, 10 mg on days 3+4, 15 mg on days 5+6, 20 mg on days 7–12, 30 mg on days 13–28 (n=34) | Leaving the study early |

| Blindness: double | Age: 18–65 years, average c. 36 years | 2. Haloperidol: dose 5 mg on days 1+2, 10 mg on days 3+4, 15 mg on days 5+6, 20 mg on days 7–12, 20 mg on days 13–28 (n=34) | Unable to use the following: | |

| Duration: 4 weeks, preceded by 3- to 7-day placebo wash-out period | Gender: male, 91; female, 12 | 3. Placebo (n=35) | Mental state: BPRS change (no s.d. data) | |

| Design: parallel, multicentre | History: acute relapse, BPRS score > 30 and score of > 4 on two of four positive symptoms, evidence of previous response to antipsychotic medication | Global state: CGI severity scale (no usable data) | ||

| Setting: in-patient, USA | ||||

| Consent: not described | ||||

| Loss: described | ||||

| Daniel et al (Reference Daniel, Saha and Ingenito2000) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM–IV) n=307 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 2 mg/day (n=59) | Leaving the study early |

| Blindness: double | Age: 18–65 years, average c. 38 years. | 2. Aripiprazole: dose 10 mg/day (n=60) | Unable to use the following: | |

| Duration: 4 weeks, preceded by 3- to 7-day wash-out period | Gender: male, 247; female, 60 | 3. Aripiprazole: dose 30 mg/day (n=61) | Global state: CGI (no s.d. data) | |

| Design: parallel, multicentre | History: acute relapse, BPRS score > 36 and score of > 2 on four criteria, antipsychotic medication taken for > 72 hours before randomisation | 4. Haloperidol: dose 10 mg/day after 5 mg/day on days 1+2 (n=63) | Mental state: BPRS, PANSS (no s.d. data) | |

| Setting: in-patient | 5. Placebo (n=64) | General functioning: CGI (no s.d. data) | ||

| Adverse effects: reported adverse effects, extrapyramidal side-effects, mean weight gain, mean prolactin levels (no usable data) | ||||

| Kane et al (Reference Kane, Carson and Kujawa2003) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM–IV) n=300 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 15–30 mg/day, average dose 28.8 mg/day (n=154) | Leaving the study early |

| Blindness: double (during treatment phase) | Age: mean c. 42.1 years | 2. Perphenazine: dose 8–64 mg/day, average dose 39.1 mg/day (n=146) | Mental state: response Adverse effects | |

| Duration 6 weeks, preceded by 14-day patient screening, 2-day neuroleptic wash-out, 4–6 weeks' confirmation of treatment resistance, 2- to 10-day neuroleptic wash-out | Gender: male, 208; female, 92 | Quality of life: QLS scores | ||

| Design: multicentre, parallel | History: treatment resistant, mean age at first hospitalisation 23 years, PANSS total score of > 75 and score of > 4 on two or more specified PANSS items, CGI severity of illness score of > 4 | Unable to use the following: | ||

| Setting: unknown | Mental state: PANSS-derived BPRS (no s.d. data) | |||

| Adverse affects: AIMS, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, SAS, mean prolactin levels, ECG changes, vital signs, body weight (no usable/s.d. data) | ||||

| Kern et al (Reference Kern, Cornblatt and Carson2001) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder n=256 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 30 mg/day (n=128) | Adverse effects: spontaneously reported adverse effects occurring in > 10% of participants, clinically significant weight gain |

| Blindness: open-label | Age: 18–65 years, average c. 40 years | 2. Olanzapine: dose 15 mg/day, after 10 mg/day on days 1–7 (n=127) | Unable to use the following: | |

| Duration: 26 weeks | Gender: male, 164; female, 92 | Adverse effects: mean change in weight, median change in serum cholesterol levels (no s.d. data) | ||

| Design: multicentre, parallel | History: chronic stable, not hospitalised for > 2 months before randomisation, previously on stable dose of antipsychotic for > 2 months | Cognitive functioning: California Verbal Learning Test, Benton Visual Retention Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Trail Making A and B, Continuous Performance Test, verbal fluency, letter–number sequencing from the WAIS–III, Grooved Pegboard Test (no usable s.d. data) | ||

| Setting: out-patient | ||||

| Kujawa et al (Reference Kujawa, Saha and Ingenito2002) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia n=1294 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 30 mg/day, with possibility of one-off dose decrease to 20 mg for tolerability (n=861) | Leaving the study early |

| Blindness: double | Age: 18–65 years, average c. 37 years | 2. Haloperidol: dose 10 mg/day, with possibility of decrease to 7 mg for tolerability (n=433) | Unable to use the following: | |

| Duration: 52 weeks | Gender: male, 758; female, 536 | Global state: response (no usable data) | ||

| Design: parallel, multicentre | History: acute exacerbation, baseline PANSS score of 95, history of previous response to antipsychotic medication | Mental state: PANSS total score, PANSS negative sub-scale score, MADRS total score, PANSS depression item, PANSS depression/anxiety cluster, PANSS negative sub-scale score (no s.d. data) | ||

| Setting: unknown, USA and Europe | Adverse effects: SAS, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, AIMS, body weight, serum prolactin levels, vital signs, ECG changes (no usable/s.d. data). | |||

| McQuade et al (Reference McQuade, Jody and Kujawa2003) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia n=317 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 15–30 mg/day (n=156) | Leaving the study early |

| Blindness: double | Age: average c. 38 years | 2. Olanzapine: dose 10–20 mg/day (n=161) | Unable to use the following: | |

| Duration: 26 weeks | Gender: male, 229; female, 88 | Global state: CGI (no usable data) | ||

| Design: parallel, multicentre | History: acute relapse, mean age at first episode c. 25 years, mean time since current acute episode began c. 21 days | Mental state: PANSS total score (no s.d. data) | ||

| Setting: unknown | Adverse effects: mean change in weight (no s.d. data), clinically significant weight gain, serum prolactin levels, extrapyramidal side-effects, plasma lipids outside normal limits (no usable data) | |||

| Consent: not described | ||||

| Loss: described | ||||

| Potkin et al (Reference Potkin, Saha and Kujawa2003) | Allocation: randomised (method not described) | Diagnosis: schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorder (DSM–IV) n=404 | 1. Aripiprazole: dose 20 mg/day (n=101) | Leaving the study early |

| Blindness: double | Age: 18–65 years, average c. 39 years | 2. Aripiprazole: dose 30 mg/day (n=101) | Adverse effects: self-reported in > 5% of participants, mean change in body weight, mean change in serum prolactin levels, mean change in QTc interval | |

| Duration: 4 weeks, preceded by 5-day placebo wash-out period | Gender: male, 283; female, 121 | 3. Risperidone: dose 2 mg on day 1, 4 mg on day 2, 6 mg/day thereafter (n=99) | Unable to use the following: | |

| Design parallel, multicentre | History: acute relapse, responsive to antipsychotic medication other than clozapine, out-patient for > 3 months in past year, PANSS total score of > 60 and score > 2 on psychotic symptom sub-scale, adequate time interval since receiving previous antipsychotic | 4. Placebo (n=103) | Global state: CGI much or very much improved (no s.d. data) | |

| Setting: hospital, USA | Mental state: PANSS – 30% decrease in baseline score, PANSS-derived BPRS (no s.d. data) | |||

| Adverse effects: SAS, Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale, AIMS, vital signs (no usable data/s.d. data) |

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; SAS, Simpson–Augus Scale; AIMS, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale; ECG, electrocardiogram; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; WAIS–III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale version III

Most of the studies were conducted in North America or Europe and involved between 103 (Reference Csernansky, Garbutt and GoffCsernansky et al, 2002) and 1294 (Reference Kujawa, Saha and IngenitoKujawa et al, 2002) participants. Most of the participants were male inpatients in their thirties or forties. The majority had well-defined diagnoses of schizophrenia with little comorbidity. Such individuals represent a minority of patients in everyday care. However, we would also like to point out that there is variation in the clinical condition of the patients who were randomised in the different studies. Although the majority of the participants were noted to have had an acute relapse of schizophrenia, in some studies the participants had chronic stable schizophrenia or treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Any interpretation of the findings of the meta-analyses must take into account this clinical heterogeneity, and the fact that it could make our findings more rather than less applicable to everyday care.

Aripiprazole was compared with placebo in 6 studies (encompassing a total of 1628 patients), with haloperidol in 4 studies (n=1913), with perphenazine in 1 study (n=300), with olanzapine in 2 studies (n=573) and with risperidone in 1 study (n=301). Aripiprazole was given over a wide range of doses (2-30 mg/day) (Reference Dubitsky, Harris and LaughrenDubitsky et al, 2002). Two studies reported deaths (Reference Carson, Ali and SahaCarson et al, 2000; Reference Adson, Bari and BonaAdson et al, 2002) but did not supply usable outcomes, although data were available on the FDA website. We found no usable data on service outcomes, general functioning, behaviour, engagement with mental health services, satisfaction with treatment, economic outcomes or cognitive functioning. Although relapse was the primary outcome measure for this review, only one study that compared aripiprazole treatment with placebo (Reference Carson, Pigott and SahaCarson et al, 2002) provided data on this outcome, and relapse in that study was defined by changes in rating scale scores, not by re-hospitalisation rates as are commonly used. Seven of the 10 studies that were included reported data in terms of both a last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) analysis and an observed-cases analysis (where observed cases are defined as those who completed the trial). We could not use the LOCF data because of the high drop-out rates reported in the studies as well as the tendency to report mean figures without providing a measure of variance.

More participants who were allocated to aripiprazole completed the studies compared with those allocated placebo (n=1658, 6 RCTs, RR (leaving study for any reason)=0.68, 95% CI 0.55-0.86; NNT=4, 95% CI 6-11). However, aripiprazole showed no significant advantage over typical antipsychotics (n=2213, 5 RCTs, RR (leaving study for any reason by 12 weeks)=0.90, 95% CI 0.76-1.05; see Fig. 1). In total, 52% of participants left these 5 studies early. If an LOCF analysis were to have been used, this would have meant that large assumptions would have to be made about the outcomes of over half the participants. Before we viewed the data, we had stated that making such assumptions for over 40% of participants rendered the outcomes impossible to interpret. In the comparison with the other atypical antipsychotic medications, 53% of the patients who were allocated aripiprazole treatment left the studies before the end of the trial, compared with 58% of the patients in the comparison groups (n=618, 2 RCTs, RR (leaving for any reason)=1.05, 95% CI 0.93-1.19). When drop-out was due to adverse effects, again we found no significant difference between aripiprazole and other atypical antipsychotics (n=618, 2 RCTs, 5% v. 8%, RR=0.78, 95% CI 0.42-1.42).

Fig. 1 Comparison of aripiprazole with placebo in participants who left the study early for any reason.

There were significantly fewer relapses among patients who were given aripiprazole compared with those who were allocated placebo (relapse by 12 weeks: n=310, 1 RCT, RR=0.59, 95% CI 0.45-0.77; NNT=5, 95% CI 4-8; relapse by 26 weeks: n=310, 1 RCT, RR=0.66, 95% CI 0.53-0.81; NNT=5, 95% CI 4-8). This study defined relapse as either a Clinical Global Impression (CGI; Reference GuyGuy, 1976) rating of minimally worse, or a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Reference Kay, Fiszbein and OplerKay et al, 1987) rating of moderately severe on hostility or uncooperativeness on two successive days, or an increase in total PANSS score of 20% or more compared with the score at randomisation (Reference Carson, Pigott and SahaCarson et al, 2002). Patients who were allocated aripiprazole were at less risk of poor compliance with the study protocol because of lack of efficacy, deterioration or psychosis. Significantly fewer patients who were allocated aripiprazole compared with those who were given placebo experienced this deterioration (n=1348, 5 RCTs, RR (by about 12 weeks) =0.66, 95% CI 0.49-0.88; NNT=15, 95% CI 10-41). No difference was found between aripiprazole and either the typical antipsychotic drugs haloperidol and perphenazine (n=2213, 5 RCTs, RR=1.1, 95% CI 0.91-1.32) or the atypical antipsychotic drugs olanzapine and risperidone for this same global outcome (n=618, 2 RCTs, RR=1.76, 95% CI 0.87-3.54).

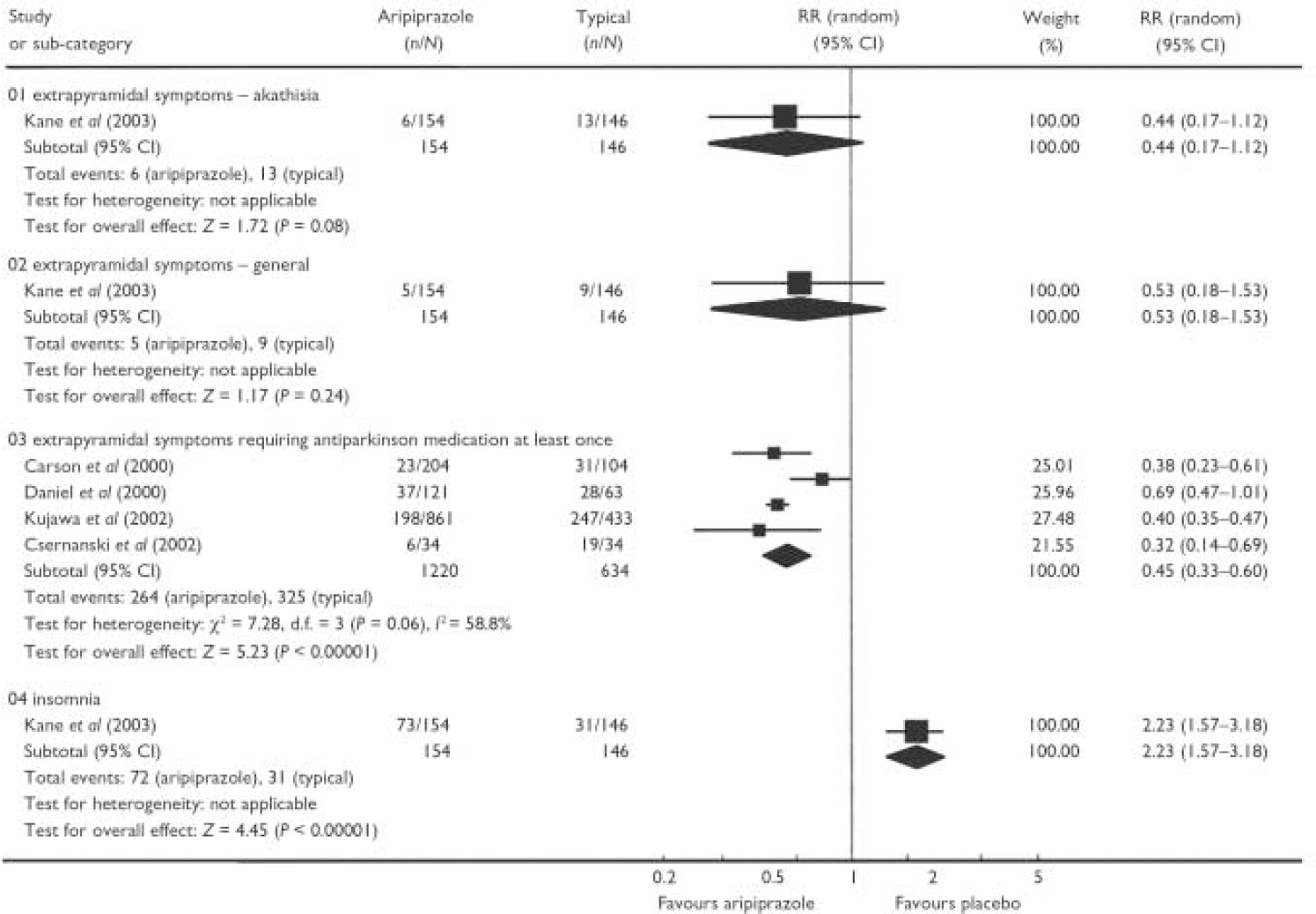

Aripiprazole had a favourable effect compared with placebo on a range of adverse effects, including headache (n=615, 2 RCTs, RR=1.04, 95% CI 0.76-1.43), anxiety (n=615, 2 RCTs, RR=0.86, 95% CI 0.53-1.39), weight gain (n=615, 2 RCTs, RR=2.64, 95% CI 0.70-9.95), extrapyramidal side-effects (n=615, 2 RCTs, RR=1.63, 95% CI 0.15-17.55) and changes in QTc interval (aripiprazole 20 mg) (n=204, 1 RCT, 95% CI 73.19 to 9.19). Aripiprazole did appear to be significantly superior to placebo in terms of the number of patients who showed a rise in serum prolactin level to at least 23 ng/ml in one short study (n=305, RR=0.32, 95% CI 0.13-0.81; NNT=14, 95% CI 11-50) (Reference Potkin, Saha and KujawaPotkin et al, 2003). Because of high drop-out rates and underreporting in the included studies, we could only derive data on adverse effects for aripiprazole compared with typical antipsychotics from a single study which used a perphenazine control (Reference Kane, Carson and KujawaKane et al, 2003). The results suggest that there is little significant difference in specific adverse effects between aripiprazole and this typical antipsychotic (Fig. 2), apart from the finding that patients who were allocated aripiprazole required less antiparkinsonian medication (NNT=4, 95% CI 3-5) and more often experienced insomnia (NNH=4, 95% CI 3-9). No outcomes were available to allow comparison of aripiprazole with typical antipsychotic medication with regard to changes in the QTc interval.

Fig. 2 Comparison of aripiprazole with typical antipsychotics with regard to adverse effects.

When combined, two trials that compared aripiprazole with other atypical antipsychotics failed to show any difference between the new drug and the other atypicals for the outcome of weight gain of 7% or more above baseline (n=556, RR=0.49, 95% CI 0.12-1.94) (Fig. 3). Aripiprazole treatment at a dose of 20 mg/day resulted in significantly less change in QTc interval than risperidone in the short term (n=200, 1 RCT, weighted mean difference -6.0, 95% CI -13.11 to 1.11), and this remained true for higher doses of aripiprazole. Treatment with aripiprazole was associated with significantly less risk of an increase in prolactin levels above 23 ng/ml than 6 mg/day of risperidone (n=301, RR=0.04, 95% CI 0.02-0.08; NNT=2, 95% CI 1-2.5), but the clinical implications of this are unclear. Overall there appeared to be few differences between aripiprazole and other atypical antipsychotics, but more well-designed and adequately reported studies are needed to demonstrate whether this is indeed the case.

Fig. 3 Comparison of aripiprazole with other atypical antipsychotics with regard to adverse effects.

Eight people who were allocated aripiprazole are known to have died in open-label extension arms of two of the studies (total n=834) (Reference Carson, Ali and SahaCarson et al, 2000; Reference Adson, Bari and BonaAdson et al, 2002). However, the authors note that the causes of these eight deaths included suicide. The people who were randomised in these two trials were experiencing an acute relapse of schizophrenia, and this may partly explain the observed mortality figures. None of these deaths occurred in the randomised controlled phase of these trials.

DISCUSSION

Limitations of data on deaths

Despite the eight deaths reported in the results section above, this research finding has not been widely disseminated. Also, on the FDA website, a number of additional deaths are reported in those known to be allocated to aripiprazole in various trials. However, we have been informed by the pharmaceutical company in question that these deaths did not occur in trials relevant to this review. We are in continued dialogue with Bristol-Myers Squibb, and hope to gain further clarification on these and other data. Not disseminating clear information regarding these people's outcome, we argue, breaks that unspoken contract that occurs between researchers and trial participants at the point of gaining informed consent. Formalising the contract of informed consent, public registration of all future trials before randomisation and clearer dissemination of trial data are all essential steps in rectifying this situation.

Other data limitations

Many of the data used in this review were obtained from conference proceedings and posters, making extraction difficult and double-counting likely. No serious published attempt was made to give each study a unique identifier. A total of 16 relevant studies, including a number of Japanese phase II and phase III studies, were only available on the FDA website and could not be included because the data were incomplete (Reference Dubitsky, Harris and LaughrenDubitsky et al, 2002). Therefore we cannot include these studies without the express assistance of the pharmaceutical companies who own the material. Multiple requests for further information on the highlighted FDA-identified trials have been made by telephone, by e-mail and in person. It is unlikely that patients who gave their informed consent would have understood that their results would remain undisclosed and would therefore not help to inform the care of other people with schizophrenia.

These studies were not designed to provide results of great relevance to everyday care. They were designed in line with the stipulations of the drug regulatory authorities. The majority of trials included well-defined study participants with little comorbidity. The typical antipsychotic drugs of comparison reported in this review were occasionally of such a nature or used at such a dose that they distanced these trials even further from everyday practice. The outcomes are remarkably few in number, of limited duration and poorly reported, and they take little account of the CONSORT statement (Reference Moher, Schulz and AltmanMoher et al, 2001), or else they carry such assumptions as to render them meaningless. Accordingly, findings from these studies are difficult to translate into meaningful decisions about patient care. Where complete data on adverse effects are available, the decision to report only events which occur in at least 5-10% of participants means that rare serious adverse events are not recorded. Large amounts of data could not be used for this review, partly because of the poor quality of reporting. Many studies failed to provide standard deviations when reporting mean changes in a particular outcome measure. Other studies failed to report outcomes in more than 40% of randomised patients. In accordance with our protocol (see above section on data analysis), we believe that including data from this population would involve making too many assumptions about final outcomes, and that these data should not be used until further information has been obtained.

Recommendations and implications

We recommend that there should be greater compliance with CONSORT guidance in future studies. The allocation of unique study identifier numbers to minimise confusion, performing an intention-to-treat analysis on all outcomes, and clear presentation of all study data are critical to this process.

This systematic review suggests that aripiprazole does not differ significantly from some typical or other atypical antipsychotics in terms of several global outcomes and adverse effects. However, it does not appear to cause hyperprolactinaemia, an adverse effect that is commonly seen with the typical antipsychotics and even with some of the other atypical antipsychotics. There appeared to be no significant difference in prolongation of the QTc interval compared with placebo, but there was less change in the QTc interval in one study that compared aripiprazole with other atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, n=200 patients). No data were available on the effect on QTc interval compared with typical antipsychotics. Aripiprazole may cause more insomnia than typical antipsychotics, but is perhaps also associated with less need for antiparkinsonian medication. However, the authors acknowledge that because of the lack of available evidence, and the limited numbers of comparator drugs that were used in these trials, further studies using a wider range of comparator drugs may be required before the results can be generalised to an antipsychotic class (either typical or atypical) as a whole.

Aripiprazole is an interesting compound with a novel mechanism of antipsychotic action, but its real effects are unclear, partly as a consequence of the requirements of both the regulatory authorities and the pharmaceutical industry. This review effectively demonstrates why large, long, well-designed, well-conducted and adequately reported pragmatic RCTs should be part of the regulatory authority's requirements. It also illustrates the way in which clinicians, recipients of care, policy makers and even those who work in the pharmaceutical industry are compromised by the limitations of using explanatory trials as the sole basis for allowing a drug to be given a national licence.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gill Rizzello, Mark Fenton and John Rathbone for help with the literature search and with the preparation and editing of this document.

The work received the intramural support of the University of Leeds and Ospedale Niguarda Ca'Granda.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.