During the 113th Congress, Diana DeGette, Democrat from Colorado’s 1st District, was known for giving “women’s health Wednesday” speeches, to bring attention to the gendered inequities in the healthcare that women receive, and was one of the primary forces pushing for the creation of the Violence Against Women Office in the Department of Justice. Rick Renzi, Republican representing Arizona’s 1st District in the 2000s, used his perch on the Resources Committee to provide increased government funds for the Native American tribes in his district. Kathy Castor, former representative of Florida’s 11th District, fought to prevent changes to Medicare that she saw as harmful to seniors. Each of these members had the same goal – to represent a particular disadvantaged group – but each pursued a different method of achieving this goal. What explains these tactical differences?

A consciously cultivated legislative reputation is one of the main ways that representatives communicate their priorities to constituent groups and demonstrate that they are working on their constituents’ behalf. When it comes to building these reputations, members of Congress have an enormous amount of discretion when it comes to the means by which they choose to signal that they are working to serve as a particular group advocate.Footnote 1 As discussed in Chapter 2, this broad range of potential actions generally necessitates that representation scholars make a priori assumptions about the types of representative acts that members will seek to engage in, and then use measures of those activities to draw conclusions about the quality of representation members provide. But because this project introduces a measure of representation that does not rely on these specific assumptions, I am able to work backwards to investigate what actions members of Congress with reputations for advocacy actually chose to utilize to represent a particular group.

In Chapter 3, member reputation and its key characteristics are described at great length. One of the primary advantages to utilizing member reputation as a way of conceptualizing and measuring the representation that members of Congress offer to disadvantaged groups is that it does not depend upon these a priori assumptions about which legislative actions a member will choose to engage in to provide that representation. Instead, this measure captures the considerable latitude members of Congress have in their tactical decision-making. To highlight the importance of these myriad representational methods, in Table 3.2, I presented preliminary evidence of the strategic differences among advocates of disadvantaged groups in the extent to which they employ common tools like bill sponsorship and cosponsorship as a means of building their legislative reputations. This initial analysis demonstrated that member reputations are not synonymous with bill introduction and cosponsorship behaviors, and there is great variation in when and to what extent these specific tools are utilized.

In this chapter, I specifically address the reasons behind this tactical variation. I examine when and why members of Congress who build their reputation as an advocate for disadvantaged groups make the decision to exercise that advocacy through the common representational tools of bill sponsorship and cosponsorship. To begin, I will discuss the reasons why bill sponsorship and cosponsorship are important and worthwhile legislative actions to consider. Next, I will introduce a theory for how the type of reputation a member is seeking to build, and for whom, as well as their place within Congress’ institutional structures, impacts which type of legislative tools members of Congress choose to lean on to build their legislative reputations. Finally, I analyze the effects of advocacy reputations and institutional position on sponsorship and cosponsorship activity using a series of ordinary least squares regression models.

6.1 Reputation and the Use of Representational Tools: Bill Sponsorship and Cosponsorship

There is a broad consensus among legislative scholars that sponsorship and cosponsorship can be important opportunities for members to engage in individual agenda setting (Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner and Jones, 1993; Reference KogerKingdon, 2005). Though it is true that any given act of sponsoring or cosponsoring a bill is highly unlikely to result in actual changes in the law, these actions are seen as offering an important signal for a member’s representational priorities and preferences. Sponsorship and cosponsorship are legislative actions that are relatively low-cost when it comes to a member’s time and energy (particularly cosponsorship, which does not require any new policy ideas or staff energy to prepare legislative text). This makes these actions very different from activities like roll-call votes or calling a committee hearing, which require institutional power and collective action from a number of different members working together.

As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 2, the symbolic role for bill sponsorship and cosponsorship has been a particular point of emphasis for scholars evaluating the impact of having descriptive representatives in the legislature (i.e., Reference CanonCanon, 1999; Reference SwersSwers, 2002, Reference Szaflarski and Bauldry2013; Reference BrattonBratton, 2006; Reference DolanDodson, 2006; Reference CarnesCarnes, 2013). Research in this vein essentially uses sponsorship, cosponsorship, or other actions as a proxy for representation, and then seeks to determine what sorts of characteristics (for instance, being a woman, a person of color, or someone from a working class background) are associated with increased sponsorship, cosponsorship, and so on. These associations are then used as a broader argument for why members with these characteristics offer better representation for the groups in question. This research has been extremely valuable for representation scholars, and has offered great insight into the quality of representation different members can provide. That said, this methodological formulation has meant that some interesting avenues of inquiry have been previously unavailable. As a result of the necessary a priori assumption that individuals seeking to engage in representation will sponsor or cosponsor bills, any nuanced differences in who chooses to engage in these particular behaviors and when have largely remained hidden.

Analyzing representation through the lens of a member’s legislative reputation bypasses the need for a starting assumption about which legislative actions are most likely to be chosen as a means of signaling representation, and allows for an exploration of those nuances in the choice of representative actions different group advocates may undertake. Members must make strategic decisions about which actions they will engage in to get their intended message to be picked up by the Congress-watchers in the media, and then hopefully transmitted back to their constituents.

In an ideal world, a legislator might want to equally represent all groups present in their district, and to do so in as many ways as possible. In reality, though, members must make choices about which groups they are going to focus on, and the best ways to engage in that representation given the very real constraints on their time and resources. Member decision-making becomes particularly interesting when considering members who choose to advocate for different disadvantaged groups. These members are faced with the task of selecting representative actions that are most likely to draw attention and approval from the members of a targeted disadvantaged group (or those who view the group with sympathy), while not also alienating those who view potential government action to help a particular group with more skepticism.

Any member who has developed a reputation for disadvantaged-group advocacy has only gotten to that point by answering two specific questions: first, do they wish to be known by their constituents as an advocate for a particular disadvantaged group (or groups), and second, how are they going to build that reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate? In answering the first question, members consider a variety of factors, including the size of the group in their district, feelings toward that group, and their own personal experiences. As shown in the previous two chapters, members of Congress are generally more likely to form a reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate when the group has a relatively large presence in their district, when that group is held in positive regard by other constituents, and when they themselves are a member of that disadvantaged group.

The second question, regarding the choice in the tactics a member selects when seeking to build or maintain their legislative reputation, particularly in service to disadvantaged groups, has not been directly addressed in prior research. The final component of this book sheds light on this question in two ways. First, given the centrality of symbolic bill sponsorship and cosponsorship as representational actions, this chapter investigates the circumstances under which members do choose to cultivate their reputations as advocates by devoting a considerable portion of their bill sponsorship and cosponsorship activities to bills relevant to a particular disadvantaged group, as is commonly assumed in the congressional representation literature. Second, this chapter highlights the groups for which members elect not to use bill sponsorship or cosponsorship as an important component of their advocacy, despite their commitment to representing a particular disadvantaged group.

6.2 When Do Members of Congress Use Bill Sponsorship and Cosponsorship as Reputation-Building Tactics?

Broadly speaking, I expect that members of Congress with reputations for disadvantaged-group advocacy are indeed going to be more likely to devote a large proportion of their bill sponsorship and cosponsorship activity to bills that can impact their group. This expectation is in line with the assumption in the prior research that sponsorship and cosponsorship are important for representation. Within those broad strokes, however, lies important nuance. Recognizing this, I argue that there are two primary conditions driving when a member of Congress may choose bill sponsorship or cosponsorship as their primary means of representing a disadvantaged group. The first of these conditions is the extent to which a particular disadvantaged group is considered to be deserving of government action on their behalf. Second, a member’s representational choices are impacted by how well a group’s issues fit in line with the breakdown of standing committees and subcommittees.

Not all disadvantaged groups are held in the same regard by non-group members. Instead, there are three broad categories of groups that can largely be delineated by the degree to which the group is considered to be deserving of government assistance, as discussed in greater detail in Chapter 2. To review, those general categories are as follows: those generally considered to be highly deserving of government programming (such as veterans and seniors), those toward whom the public is neutral or has mixed feelings (such as women, immigrants,Footnote 2 Native Americans, and the poor), and those largely considered to be undeserving of government assistance (such as racial/ethnic minorities and the LGBTQ community.)

I expect that members of Congress will condition their decisions about which representational tactics to deploy as a group advocate as a result of these differences in the perceptions of group deservingness of government assistance. This conditioning, however, looks slightly different for cosponsorship decisions than it does for sponsorship decisions.

6.2.1 Bill Cosponsorship

Cosponsorship is an important but extremely low cost means by which members can take a position and engage in agenda setting (Reference ArnoldArnold, 1990; Reference KingdonKessler and Krehbiel, 1996; Reference WayneWawro, 2001; Reference Kramarow and PastorKoger, 2003). As a result, I argue that members primarily consider two main factors when deciding whether or not to cosponsor a bill on behalf of a disadvantaged group, assuming they generally agree with the bill’s premise. First, they consider the potential visibility of their action. In other words, how likely is it that important media observers will notice their action, and incorporate it into the reputation that is transmitted to their constituents? Second, they consider any potential risk involved in associating themselves with a particular piece of legislation. In short, is this action likely to result in the alienation or aggravation of other groups, so that any increased visibility has a negative effect?

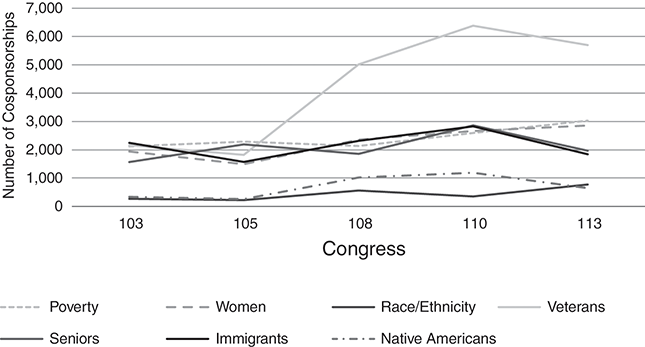

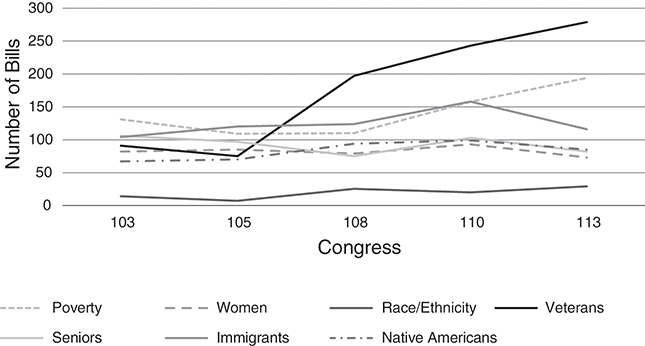

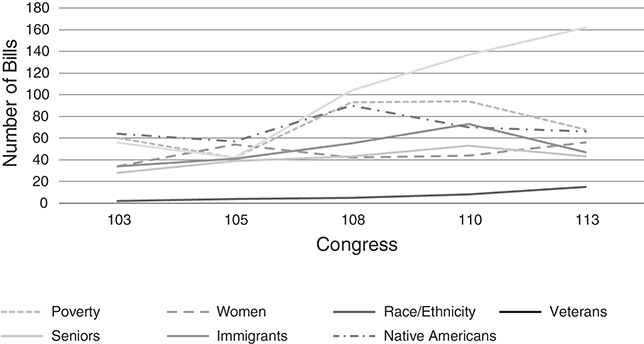

Visibility takes into account the environment a member is in, and the likelihood that a particular action will be noticed. Actions that are less common are going to be more visible than actions that are more common. Figures 6.1 and 6.2 show the frequency of cosponsorships across a variety of group-specific areas for five Congresses in the House and the Senate. Generally speaking, the rarity of cosponsorship activity is inversely related to the perceived deservingness of a disadvantaged group. Vastly more cosponsorships of bills related to the needs of veterans occur in a given Congress (particularly for the post-9/11 108th, 110th, and 113th Congresses) than those of bills pertaining to any other group. On the opposite end, on average, there are considerably fewer cosponsorships of bills that could potentially benefit racial and ethnic minorities.

Figure 6.1 Group-specific bill cosponsorship in the House, by Congress

Note: Figure displays total cosponsorships pertaining to each group in a given Congress.

Figure 6.2 Group-specific bill cosponsorship in the Senate, by Congress

Note: Figure displays total cosponsorships pertaining to each group in a given Congress.

Cosponsoring a bill that could benefit a group considered to be highly deserving of government assistance holds little to no risk to a member of Congress. Signing on to legislation to benefit groups with an intermediate level of perceived deservingness carries a corresponding low to medium amount of risk. Bills intended to assist groups that are considered to be less deserving are markedly riskier. For example, more potential backlash might be expected in cosponsoring a bill advocating for a committee to study reparations for descendants of enslaved African Americans than a bill aiming to prevent older Americans being scammed by robocallers.

For groups with a high level of perceived deservingness of government action, visibility may be fairly low, but so is the risk. As cosponsorship requires little of a member in the way of time, effort, and resources, I would expect that any member who wants to be seen as dedicating some portion of their legislative reputation to one of these groups would find cosponsorship to be a worthwhile activity. Similarly, while there may be slightly higher risk for a group that has a mixed level of perceived deservingness of assistance, it is balanced by marginally higher visibility. Members seeking to be known as representing these groups are thus likely to choose cosponsorship as a valid representational tactic. Yet, for groups with low levels of perceived deservingness of government assistance – namely racial and ethnic minorities – even a low-energy activity like cosponsorship results in potentially high visibility and increased risk of negative repercussions. Thus, I expect that only members who are particularly committed to devoting a considerable portion of their legislative reputation to advocating for racial and ethnic minorities will engage in related cosponsorship.

6.2.2 Bill Sponsorship

Bill sponsorship, while still of great use as a symbolic representational tool, is different from cosponsorship in important ways. Bill sponsorship requires a greater outlay of effort from a member of Congress than cosponsorship, which simply expresses support for someone else’s legislation. To sponsor a bill, a member must either have their own original policy idea or spend time in contact with interest groups or other individuals who have a specific policy idea in mind. Further, the member and their staff must devote time and resources to transforming that idea into appropriately formatted legislative language. As sponsored bills have a member’s name most directly attached, members also bear greater responsibility for the ideas contained within, which can be beneficial or problematic, depending on the circumstances. This makes bill sponsorship generally more risky as a symbolic action than cosponsorship.

While risk may be higher for sponsorship relative to cosponsorship, the general patterns of visibility are similar, as seen in Figures 6.3 and 6.4. But given these important characteristics of bill sponsorship, members’ sponsorship decisions are conditioned by an additional factor that members may not take into account for bill cosponsorship. While members of Congress still consider the visibility and risk involved in sponsorship activities, because of the additional effort required, they also factor in the likelihood that a bill could actually gain the support it would require to pass. This is not to say that passage is a purely necessary or sufficient condition; other factors may lead a member not to sponsor a bill that could potentially be popular, or to sponsor a bill that is highly unlikely to ever go anywhere. However, members still consider the possibility before deciding whether or not the time and resources required to sponsor a bill are worth it.

Figure 6.3 Group-specific bill sponsorship in the House, by Congress

Note: Figure displays total sponsorships pertaining to each group in a given Congress.

Figure 6.4 Group-specific bill sponsorship in the Senate, by Congress

Note: Figure displays total sponsorships pertaining to each group in a given Congress.

Sponsoring bills with the potential to benefit groups that are considered to be less deserving of government assistance may be visible and risky, as discussed earlier, but those bills also are much less likely to gain the support they would need to eventually pass. For a member who devotes a smaller portion of their reputation to serving one of these disadvantaged groups, these circumstances are likely to make bill sponsorship a less appealing means of representing the group than other potential representational actions. A member seeking to devote a high level of their sponsorship activity to benefit a group that is generally thought to be deserving of government assistance must consider a rather different set of factors. The risk of backlash is low, but so is potential visibility. This lends a high level of uncertainty to the possibility of a sponsored bill actually passing. Because sponsoring a non-controversial bill on behalf of a well-regarded group can be a popular idea, eventual passage is likely dependent upon other institutional factors (particularly the committee system, the effects of which are discussed in greater detail below). I expect that bill sponsorship will be most common among members seeking to build any level of reputation as an advocate for a disadvantaged group that is generally held with more mixed perceptions of deservingness, because all three factors – risk, visibility, and potential for passage – tend to be at more moderate levels.

6.2.3 Differences in Expectations between the House and the Senate

There are 435 members of the House of Representatives, compared to only 100 in the Senate. This means that in the Senate, every action that is taken has a higher level of visibility relative to the House. There are two expected side-effects of this greater visibility. First, senators are likely to be able to build their reputations more easily, because they are not fighting for media attention with as many other members. I anticipate that the magnitude of the effects of member reputation in the Senate will be lower than in the House, because senators may have to take fewer individual actions to build or maintain their reputations. Second, because of this higher level of visibility, senators are likely to be more cautious in their risk assessment, particularly for groups with lower levels of perceived deservingness of government assistance, and may prefer to engage in representative actions that are less likely to create a backlash from other groups in their districts.

6.3 Evaluating Bill Sponsorship and Cosponsorship Activity

I test these hypotheses using an extension of the original dataset of members of the US Senate and House of Representatives introduced in Chapter 3, and utilized in Chapters 4 and 5. This analysis again makes use of the reputation variable already described, but transforms it from an ordinal variable into a series of discrete indicators, which serve as the pivotal explanatory variables in the models to follow. To evaluate the extent to which members of Congress make the choice to engage in group-related bill sponsorship and cosponsorship as the specific means of building their legislative reputations, the subsequent models will employ two different dependent variables. These dependent variables of interest are the percentage of a member’s cosponsorship activity that is relevant to a particular disadvantaged group, and the percentage of a member’s bill sponsorship activity that is relevant to a particular disadvantaged group. I perform a series of ordinary least squares regressions to investigate the impact of member reputation and other relevant variables on sponsorship and cosponsorship activity on behalf of disadvantaged groups.Footnote 3 Each of these variables is discussed in greater detail below.

6.3.1 Reputation

As stated above, in this analysis, the reputation variable is employed not as an ordinal dependent variable, but rather as individual explanatory variables. Dichotomous variables indicating whether someone is a primary advocate, secondary advocate, or superficial advocate are included in the model as potential predictors of a member’s proclivity to sponsor or cosponsor legislation relevant to a particular disadvantaged group. For those groups with extremely limited numbers of primary advocates, those with reputations for primary and secondary advocacy are combined into a single category. This is discussed in greater detail below, in association with the relevant models.

6.3.2 Bill Sponsorship and Cosponsorship

The dependent variables for these analyses are the percentage of a member’s sponsorship or cosponsorship activities that involve bills relevant to a particular disadvantaged group. Relevant bills are determined using Adler and Wilkerson’s Congressional Bills Project dataset, which includes the Baumgartner and Jones Policy Agendas Project topic codes. These codes are used to classify every bill proposed in a given Congress into a specific issue area. Any bill with topics that are directly related to one of the disadvantaged groups examined here are included in the analysis as being a relevant potential sponsorship or cosponsorship.Footnote 4

There are fourteen total dependent variables that are utilized in the analysis to follow. These are the percentage of a member’s bill sponsorship activity that is devoted to legislation related to the poor, women, immigrants, racial/ethnic minorities, veterans, seniors, or Native Americans, as well as the percentage of a member’s cosponsorship activity on bills relevant to the same groups.Footnote 5 The choice to evaluate sponsorship and cosponsorship on behalf of particular disadvantaged groups as a percentage rather than as a count is an intentional, theory-driven decision.

Members are widely varied in their approach to bill sponsorship and cosponsorship. Some choose to sponsor or cosponsor as many bills as possible, potentially diluting their signal, even if there are a relatively large number of them. Others may only sponsor or cosponsor a few bills, but if they are consistent in their targets, they can send a clearer message than someone with more bills in terms of sheer numbers. Expressing group-specific bill sponsorship or cosponsorship as a percentage of total activity, rather than as a count of individual bills, takes into account this diversity of opportunity for member decision-making. Two members that each choose to devote 40 percent of the bills they cosponsor to those that could benefit seniors are much more similar in the representational message that they send than would otherwise be apparent by just knowing that one of these members cosponsored seventy bills to benefit older Americans, and the other just seven.

Considering group-bill sponsorship and cosponsorship as a percentage is also important because it accounts for the fact that members do not just have different preferences for the use of sponsorship and cosponsorship overall, but that these preferences can change across groups. To demonstrate this, we can consider two more hypothetical members, each with a relatively high overall tendency toward bill sponsorship, and a reputation for secondary advocacy of different disadvantaged groups. One of these members may include within their otherwise high bill sponsorship totals bills that are intended to benefit their group, while the other member may have high overall totals, but bills for their group play only a small part within that. For this first member, bill sponsorship is considered to be an important tool in maintaining their reputation, but for the second, sponsorship is clearly considered to be a less effective tool in advocating for their particular disadvantaged group, despite deploying bill sponsorship to achieve other goals within the legislature.

6.3.3 Other Variables

I include several other relevant controls in my models. First, I account for the member’s party affiliation. Given that Democrats have a reputation for being a party based more heavily on group coalitions, while Republicans are considered to be the more ideological party (Reference Haider-MarkelGrossman and Hopkins, 2016), I expect that Democrats, on average, are more likely to engage in bill sponsorship and cosponsorship activity pertaining to specific disadvantaged groups. I also account for other individual factors such as whether or not a member is a part of party leadership, coded as a dichotomous variable, where leadership includes the positions of Speaker of the House, Majority or Minority Leader, Assistant Majority or Minority Leader, and Majority or Minority Whip. Binary variables indicating if a member is a part of the congressional majority or is in their first term are included as well. The two final individual-level variables included in the models, sponsorship quartile and cosponsorship quartile, account for the overall sponsorship and cosponsorship activity of a member. Specifically, I control for whether a member is in the first, second, third, or fourth quartile among all members in a given Congress when it comes to the total number of bills sponsored or cosponsored.Footnote 6 Lastly, all models also control for congress-specific fixed effects, and display standard errors clustered by member.Footnote 7

6.4 Upholding Reputations for Group Advocacy using Bill Sponsorship and Cosponsorship

The coefficients of the models evaluating the impact of reputation and other variables indicating a member’s position within the institution (excluding committee membership, which is covered separately in the next section) on cosponsorship and sponsorship in the House of Representatives and the Senate are found in Tables 6.1–6.4. These data show that, fairly consistently, whether or not a member has a reputation for disadvantaged-group advocacy is one of the best predictors for sponsoring or cosponsoring bills related to that group. This is in line with the first broad hypothesis, that members seeking to build a reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate will be more likely to take advantage of bill sponsorship and cosponsorship as representational tools. Within this broader trend, however, there is evidence of important distinctions between the representational strategies for different disadvantaged groups. These are considered in turn below, according to the group’s perceived level of deservingness of government assistance, and the chamber in which a member operates.

6.4.1 Sponsorship and Cosponsorship Activity in the House of Representatives

6.4.1.1 Groups with High Perceived Deservingness

As seen in the first two columns of Table 6.1, members with a reputation for advocacy on behalf of groups generally seen as deserving of government assistance are significantly more likely to devote a higher proportion of their cosponsorships to bills relevant to those groups. This is true for members with reputations for advocating on behalf of both veterans and seniors, the two groups that are in this category. Because these actions are low risk and low effort, even with potentially limited visibility, it was expected that cosponsorship in the House would be popular for members with any level of reputation for advocacy.

Table 6.1 Committee membership and the percentage of bills cosponsored across disadvantaged groups in the House

| (1) Veterans | (2) Seniors | (3) Native Americans | (4) Women | (5) Poor | (6) Immigrants | (7) Race/Ethnicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Advocates | 2.738 | 0.341 | 5.361 | 2.159 | 1.991 | 2.922 | 0.655 |

| 1.048 | 0.156 | 0.236 | 1.157 | 0.187 | 0.360 | 0.072 | |

| Secondary Advocates | – | – | – | 1.157 | 1.259 | 1.882 | 0.423 |

| 0.179 | 0.123 | 0.332 | 0.056 | ||||

| Superficial Advocates | 2.279 | 0.238 | 1.515 | 0.421 | 0.453 | 1.092 | 0.287 |

| 0.217 | 0.102 | 0.182 | 0.134 | 0.087 | 0.231 | 0.048 | |

| Cosponsorship Quartile | 0.221 | 0.208 | −0.006 | 0.267 | 0.129 | 0.149 | 0.003 |

| 0.056 | 0.030 | 0.020 | 0.031 | 0.032 | 0.042 | 0.012 | |

| Sponsorship Quartile | 0.005 | −0.020 | 0.050 | −0.016 | −0.035 | −0.027 | −0.001 |

| 0.053 | 0.028 | 0.019 | 0.029 | 0.030 | 0.039 | 0.011 | |

| Republican | −0.688 | −0.109 | −0.245 | −1.437 | −0.839 | 1.212 | −0.182 |

| 0.113 | 0.059 | 0.041 | 0.062 | 0.066 | 0.084 | 0.025 | |

| Leadership | −1.055 | −0.783 | 0.149 | 1.404 | 0.830 | 0.756 | 0.435 |

| 0.531 | 0.279 | 0.192 | 0.291 | 0.299 | 0.394 | 0.112 | |

| Majority | −0.531 | −0.439 | 0.018 | 0.040 | 0.402 | −0.942 | −0.277 |

| 0.108 | 0.057 | 0.039 | 0.059 | 0.061 | 0.080 | 0.023 | |

| First Term | 1.074 | −0.007 | 0.127 | 0.166 | 0.100 | −0.092 | 0.015 |

| 0.143 | 0.075 | 0.052 | 0.079 | 0.082 | 0.107 | 0.031 | |

| Constant | 4.931 | 1.549 | 0.510 | 2.632 | 2.813 | 1.355 | 0.899 |

| 0.228 | 0.120 | 0.082 | 0.125 | 0.130 | 0.170 | 0.048 | |

| N | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.332 | 0.126 | 0.300 | 0.391 | 0.300 | 0.192 | 0.274 |

Members that are in the highest quartiles for bill cosponsorship more generally are also more likely to cosponsor bills related to the needs of these groups. This further speaks to the low-risk nature of cosponsoring bills relevant to veterans and seniors. Because working on behalf of these groups that are broadly considered to be deserving of government assistance is non-controversial, it is reasonable that members who tend to cosponsor more bills across the board would not hesitate to also cosponsor bills related to these groups.

As expected, party affiliation plays only a limited role in determining which members will devote a larger share of their cosponsorship activity to bills targeting veterans and seniors. Party is not a significant factor in determining which members will engage in cosponsorship for seniors. Democrats are more likely to cosponsor veterans’ bills, but the magnitude of this effect is only a quarter of the effect from having a reputation as a primary advocate for veterans. Given the increasing levels of partisanship from the 1990s up through to the current decade, this minimal role of party affiliation is striking.

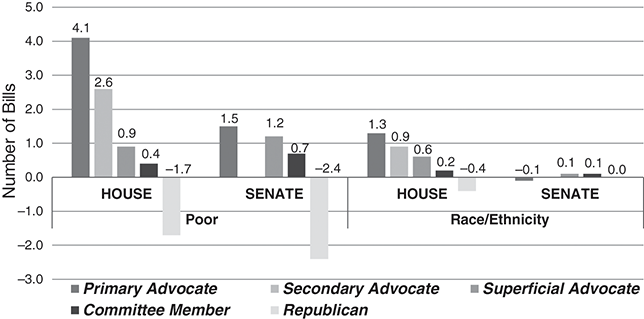

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 6.2 demonstrate that the decision by a member of the House of Representatives to sponsor a bill related to a group that is broadly considered to be deserving of government assistance is a bit more complex than that of the decision to cosponsor, as the theory would suggest. Here, those with a reputation for superficial veterans’ advocacy are more likely to sponsor a larger share of bills, while members with a reputation for primary or secondary advocacy on behalf of veterans are not significantly more likely to sponsor veterans’ bills. This pattern is reversed for those with a reputation for advocacy for seniors. Primary and secondary seniors’ advocates are more likely to devote a large portion of their sponsorship activities to legislation relevant to seniors, while superficial advocates are not.

Table 6.2 Committee membership and the percentage of bills sponsored across disadvantaged groups in the House

| (1) Veterans | (2) Seniors | (3) Native Americans | (4) Women | (5) Poor | (6) Immigrants | (7) Race Ethnicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Advocates | 6.906 | 1.787 | 17.735 | 8.988 | 4.746 | 7.450 | 2.926 |

| 3.980 | 0.558 | 1.298 | 0.843 | 0.858 | 1.472 | 0.272 | |

| Secondary Advocates | – | – | – | 2.738 | 3.487 | 9.682 | 0.838 |

| 0.588 | 0.568 | 1.332 | 0.212 | ||||

| Superficial Advocates | 6.931 | 0.598 | 8.950 | 1.020 | 0.790 | 2.261 | 0.216 |

| 0.828 | 0.365 | 1.001 | 0.443 | 0.401 | 0.925 | 0.184 | |

| Cosponsorship Quartile | −0.031 | 0.214 | 0.085 | 0.265 | 0.346 | 0.095 | −0.075 |

| 0.215 | 0.106 | 0.113 | 0.102 | 0.147 | 0.168 | 0.045 | |

| Sponsorship Quartile | −0.247 | 0.183 | −0.017 | −0.038 | 0.031 | 0.147 | 0.054 |

| 0.201 | 0.100 | 0.106 | 0.096 | 0.137 | 0.158 | 0.042 | |

| Republican | −0.491 | 0.515 | −0.044 | −0.498 | −0.324 | 0.827 | −0.024 |

| 0.429 | 0.213 | 0.225 | 0.205 | 0.303 | 0.339 | 0.093 | |

| Leadership | −1.812 | −0.388 | −1.040 | −0.354 | 6.511 | −1.097 | −0.304 |

| 2.016 | 0.998 | 1.057 | 0.957 | 1.375 | 1.580 | 0.425 | |

| Majority | −0.457 | −0.152 | −0.046 | 0.391 | 0.304 | −0.332 | −0.078 |

| 0.413 | 0.204 | 0.216 | 0.196 | 0.282 | 0.324 | 0.087 | |

| First Term | 2.294 | 0.364 | −0.086 | 0.216 | 0.046 | 0.343 | 0.170 |

| 0.547 | 0.271 | 0.287 | 0.260 | 0.376 | 0.430 | 0.116 | |

| Constant | 5.795 | −0.052 | 0.823 | 0.472 | 2.311 | 0.901 | 0.449 |

| 0.874 | 0.431 | 0.457 | 0.413 | 0.599 | 0.687 | 0.184 | |

| N | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.066 | 0.012 | 0.115 | 0.075 | 0.057 | 0.036 | 0.062 |

There are noteworthy differences when considering some of the other control variables as well. Unlike the pattern seen with cosponsorship, someone who is in the higher quartiles of bill sponsorship is not significantly more likely to sponsor bills benefiting seniors or veterans. And once again, though party affiliation is not the strongest factor in determining the percentage of sponsorship activity expended on groups that are considered to be highly deserving of government assistance, the pattern of significance has flipped for sponsorship relative to cosponsorship. In this instance, it is Republicans that are more likely to sponsor bills related to seniors. This continues to demonstrate that these trends are certainly not an exclusively partisan phenomenon. In the post-1990s polarized world, the surprising lack of clear partisan direction in sponsorship decisions stands out as important evidence that both Republicans and Democrats are still making similar evaluations about their representational choices for at least some disadvantaged groups.

6.4.1.2 Groups with Mixed Perceived Deservingness

When it comes to cosponsorship, the results of representational decision-making pertaining to groups with mixed perceived levels of deservingness look quite similar to those of high deservingness groups, as seen in columns (3)–(6) of Table 6.1. Regardless of the level of advocacy a member has a reputation for providing, cosponsorships related to women, Native Americans, immigrants, and the poor are likely to make up a broader share of a member’s overall cosponsorship activity than those members with no reputation for advocacy at all. This fits with theoretical expectations laid out for the evaluation of this relatively low risk and low effort activity.

The effects of partisanship on cosponsorship related to these groups of mixed perceived deservingness of assistance are also of note here. Cosponsorship of bills pertaining to women, Native Americans, and the poor is more likely to be carried out by Democrats, while Republicans are significantly more likely to cosponsor bills relevant to immigrants. These marginally stronger ties with Democrats are not particularly surprising, given the embrace of these groups (particularly women and the poor) among the general Democratic coalition, but the tendency of Republicans to devote a higher percentage of their cosponsorship activity to bills related to immigrants is less expected, at least from a modern perspective. This effect is likely due to two main factors. First, Republicans during this time frame were much more likely to engage in legislative advocacy on behalf of policies such as a pathway to citizenship or legal residency than is currently the case. Second, immigrants are a diverse group, and members may respond differently to the various cohorts within that group. For example, Republicans may choose to cosponsor legislation benefiting high-skilled immigrants, even if they would not cosponsor a bill seeking to limit deportations of undocumented immigrants.

When it comes to bill sponsorship decisions, as expected, the choice seems to be more straightforward for members seeking to advocate for these groups with mixed perceptions of deservingness than for those advocating for seniors or veterans. Members with reputations for any level of advocacy on behalf of Native Americans, women, the poor, or immigrants, are significantly more likely to devote a higher percentage of their sponsorship activity to legislation benefiting these groups, as can be seen in columns (3)–(6) of Table 6.2. Because there are not consistently negative perceptions of government assistance to these groups, bill sponsorship is not considered to be highly risky, and there is at least moderate potential for being able to gather the needed coalition for a bill’s eventual passage. For members deciding what proportion of their sponsored bills to devote to Native Americans or the poor, party is not a significant determining factor. For women, however, as with immigrants, party does play a significant role – this time, with Democrats more likely to sponsor a higher proportion of bills related to women’s interests, and Republicans more likely to have a higher portion of their sponsorship activity on bills related to immigrants.

6.4.1.3 Groups with Low Perceived Deservingness

The final column of Table 6.1 provides the results of the analysis of the cosponsorship decisions related to racial and ethnic minorities, which are broadly considered in the United States to be less deserving of government assistance than the other groups evaluated. As with all other group related cosponsorships in the House of Representatives that have been considered here, members with reputations for the advocacy of racial and ethnic minorities at any level are more likely to engage in a higher percentage of cosponsorship pertaining to this group. That said, the magnitude of this effect is considerably smaller for those with reputations as minority advocates than for advocates of any other group besides seniors. This implies that while those with reputations for advocacy of racial/ethnicity minorities may choose to cosponsor slightly more bills relevant to their interests, this is not the primary means by which they distinguish themselves.

As predicted, a slightly different pattern appears when considering the percentage of a member’s cosponsorship activity that is devoted to racial and ethnic minorities, as can be seen in column (7) of Table 6.3. Higher risk, higher visibility, and a diminished chance of eventual passage make the introduction of bills relevant to racial/ethnic minorities less appealing than other representational tactics for members with a reputation for only superficial forms of advocacy. Again, this does not mean that there are no members who have a reputation for superficial advocacy on behalf of racial and ethnic minorities – Figure 3.7 shows that this is clearly not the case. These other members may have built superficial reputations, but they decided that increased levels of bill sponsorship were not the right way to do it.

Table 6.3 Committee membership and the percentage of bills cosponsored across disadvantaged groups in the Senate

| (1) Veterans | (2) Seniors | (3) Native American | (4) Women | (5) Poor | (6) Immigrant | (7) Race/ Ethnicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Advocates | 2.080 | 0.681 | 6.222 | 1.401 | 1.082 | 2.189 | −0.049 |

| 0.571 | 0.222 | 0.580 | 0.289 | 0.247 | 0.623 | 0.163 | |

| Superficial Advocates | 2.115 | 0.374 | 5.323 | 0.767 | 0.795 | 0.809 | 0.073 |

| 0.391 | 0.151 | 0.652 | 0.227 | 0.180 | 0.348 | 0.118 | |

| Cosponsorship Quartile | 0.143 | 0.371 | −0.144 | −0.071 | 0.151 | −0.166 | −0.030 |

| 0.113 | 0.056 | 0.119 | 0.079 | 0.080 | 0.091 | 0.025 | |

| Sponsorship Quartile | 0.117 | −0.163 | 0.305 | −0.061 | 0.065 | 0.080 | 0.017 |

| 0.108 | 0.054 | 0.114 | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.087 | 0.024 | |

| Republican | −0.747 | −0.456 | 0.295 | −1.636 | −1.343 | 0.483 | −0.015 |

| 0.192 | 0.096 | 0.201 | 0.134 | 0.136 | 0.154 | 0.042 | |

| Leadership | 0.061 | −0.219 | 0.067 | −0.427 | 0.025 | −0.383 | 0.274 |

| 0.456 | 0.225 | 0.478 | 0.317 | 0.319 | 0.363 | 0.101 | |

| Majority | 0.023 | 0.111 | 0.161 | 0.232 | −0.360 | −0.305 | −0.019 |

| 0.195 | 0.096 | 0.203 | 0.136 | 0.137 | 0.156 | 0.043 | |

| First Term | 0.252 | −0.127 | −0.231 | 0.269 | 0.483 | 0.151 | −0.009 |

| 0.278 | 0.137 | 0.289 | 0.193 | 0.194 | 0.221 | 0.061 | |

| Constant | 4.117 | 0.654 | 0.311 | 4.108 | 2.303 | 1.504 | 0.479 |

| 0.397 | 0.195 | 0.411 | 0.273 | 0.276 | 0.314 | 0.086 | |

| N | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.325 | 0.329 | 0.293 | 0.373 | 0.304 | 0.120 | 0.128 |

There is an additional variable that is notable for not being statistically significant. After controlling for the effects of a member’s reputation as an advocate for racial/ethnic minorities on sponsorship decisions, a member’s party affiliation does not have a significant impact. This emphasizes the unique treatment of the needs of racial/ethnic minorities, relative even to the other disadvantaged groups considered. This distinction is not one that is purely rooted in partisanship, but rather the specific choices of members to build reputations as advocates of racial/ethnic minorities.

6.4.2 Sponsorship and Cosponsorship Activity in the Senate

6.4.2.1 Groups with High Perceived Deservingness

As can be seen in Tables 6.3 and 6.4, the patterns of which members are more prone to sponsoring or cosponsoring bills related to veterans and seniors – both groups with a generally high perceived deservingness of government assistance – are quite similar to those that were seen in the House, with only a few distinctions. As in the House, members with a reputation for any kind of advocacy on behalf of seniors or veterans are more likely to devote a higher percentage of their cosponsorship activity to bills relevant to those groups. In the Senate, however, Democrats are significantly more likely than Republicans to cosponsor bills pertaining to veterans and seniors, rather than exclusively veterans.

Table 6.4 Committee membership and the percentage of bills sponsored across disadvantaged groups in the Senate

| (1) Veterans | (2) Seniors | (3) Native Americans | (4) Women | (5) Poor | (6) Immigrants | (7) Race/ Ethnicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prim/Sec Advocates | 4.994 | 1.250 | 8.620 | 3.143 | 2.438 | 9.033 | −0.141 |

| 1.739 | 0.626 | 1.275 | 0.687 | 0.725 | 1.590 | 0.315 | |

| Superficial Advocates | 5.710 | 0.705 | 12.507 | 0.776 | 1.137 | 1.666 | 0.505 |

| 1.192 | 0.425 | 1.433 | 0.539 | 0.529 | 0.887 | 0.229 | |

| Cosponsorship Quartile | −0.118 | 0.431 | −0.177 | −0.239 | −0.185 | 0.215 | −0.067 |

| 0.346 | 0.159 | 0.261 | 0.189 | 0.234 | 0.232 | 0.048 | |

| Sponsorship Quartile | 0.105 | −0.265 | 0.269 | −0.132 | 0.089 | −0.263 | 0.104 |

| 0.330 | 0.152 | 0.251 | 0.180 | 0.224 | 0.222 | 0.047 | |

| Republican | −1.341 | 0.238 | 0.865 | −0.939 | −0.459 | 0.501 | −0.013 |

| 0.587 | 0.270 | 0.443 | 0.319 | 0.400 | 0.392 | 0.082 | |

| Leadership | −0.322 | −0.661 | −0.757 | −0.868 | −0.496 | 1.777 | −0.271 |

| 1.390 | 0.635 | 1.051 | 0.752 | 0.936 | 0.939 | 0.196 | |

| Majority | −0.358 | 0.465 | 0.021 | 0.382 | −0.438 | −0.430 | −0.034 |

| 0.594 | 0.272 | 0.447 | 0.323 | 0.402 | 0.397 | 0.083 | |

| First Term | 1.684 | −0.986 | −0.334 | 0.266 | 0.011 | 0.673 | −0.061 |

| 0.850 | 0.387 | 0.638 | 0.460 | 0.572 | 0.566 | 0.119 | |

| Constant | 5.419 | 0.120 | 1.278 | 2.995 | 2.851 | 1.119 | 0.319 |

| 1.217 | 0.552 | 0.909 | 0.653 | 0.816 | 0.806 | 0.169 | |

| N | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.098 | 0.027 | 0.187 | 0.065 | 0.032 | 0.077 | 0.014 |

Sponsorship activity for bills related to the needs of veterans is also higher for senators with a reputation for any level of veterans’ advocacy, unlike in the House, where primary advocates are more prone to other types of activities. Bills relevant to seniors, however, compose a higher percentage of sponsorships for members with primary or secondary reputations for advocacy, but not for those with superficial reputations. As was the case in the House, this indicates that superficial advocacy can be sufficiently communicated through cosponsorship or other activities, and sponsorship is much more commonly used as a reputation-building tool only by those that wish to be known for devoting a considerable portion of their reputation to serving seniors.

6.4.2.2 Groups with Mixed Perceived Deservingness

Members with reputations for advocacy on behalf of disadvantaged groups perceived to have a mixed level of deservingness can be seen to behave slightly differently in the Senate compared to the House, depending upon the specific group in question. Once again, choosing to engage in a higher percentage of cosponsorship activity relevant to Native Americans, women, the poor, and immigrants is significantly more common among those members with a reputation for any level of group advocacy, as seen in columns (3)–(6) of Table 6.3. The impact of partisanship on cosponsorship activity pertaining to these groups, however, is not exactly the same in the Senate as it is in the House.

Most notably, unlike in the House, cosponsorship of bills relevant to Native Americans does not have a significant partisan dimension after members’ reputations for advocacy are taken into account. This indicates that Republican senators are just as likely as Democratic senators to make the decision to cosponsor bills benefiting Native Americans, even if they are not specifically seeking to build or maintain a reputation as an advocate on their behalf. Higher cosponsorship activity related to women and the poor is still more common among Democrats, but Republicans again are more likely to utilize more of their cosponsorship agenda on legislation related to immigrants (though the magnitude of that difference is less than half the size of that in the House).

Differences between the Senate and the House are even more apparent when considering sponsorship decisions, displayed in columns (3)–(6) of Table 6.4. Senators with reputations as primary or secondary advocates are still more likely to assign a higher proportion of their sponsorship activity to bills related to Native Americans, women, the poor, or immigrants, but the same is not true for all senators with reputations as superficial advocates for one of these groups. For superficial advocates of Native Americans and the poor, sponsoring one’s own bills on issues directly relevant to these groups is used as a significant component of reputation building, while this is not the case for superficial advocates of women or immigrants.

Senators’ party affiliation also has less of a significant role to play in the sponsorship decisions pertaining to most of the groups that generally have mixed perceptions of their deservingness of government assistance. Democrats are significantly more likely to choose to devote a higher percentage of their overall bill sponsorship activity to women’s issue bills, even for senators that are not seeking to build reputations as women’s advocates. When it comes to bills relevant to Native Americans, immigrants, and the poor, on the other hand, Democratic and Republican members without reputations for advocacy are equally likely to sponsor bills related to these groups. This is especially interesting when considering bills pertaining to the poor, as economic concerns have long been a central point of differentiation between the Republican and Democratic parties.

6.4.2.3 Groups with Low Perceived Deservingness

Racial/ethnic minorities are the only group for which senators seeking to be known as an advocate do not consistently engage in a high percentage of bill cosponsorship relevant to the group. Even when bill sponsorship is considered, only senators with a reputation for superficial advocacy of racial/ethnic minorities devote a significantly higher portion of those actions to bills related to minorities. Coefficients for each of these models are found in the last columns of Tables 6.3 and 6.4. This means that regardless of the type of reputation a senator is seeking to build as an advocate of racial/ethnic minorities, cosponsorship is not considered to be an important reputation-building strategy, and additional bill sponsorship is a strategy mostly deployed by those seeking to build a reputation for the lowest level of advocacy.

Partisanship is also not a significant determining factor of the percentage of sponsorship and cosponsorship activity on bills directly related to racial/ethnic minorities in which a senator will engage. This is surprising, given the strength of the link between racial/ethnic minorities, particularly Black Americans, and the Democratic Party coalition during this time period. Because neither partisanship nor a senator’s reputation for advocacy are strong determinants of sponsorship or cosponsorship activity in most cases, this implies that advocates for racial/ethnic minorities in the Senate have a strong preference for taking other representative actions outside of sponsorship and cosponsorship.

6.5 Bill Sponsorship and Cosponsorship and the Committee Structure

How deserving of government assistance a group is generally perceived to be explains a considerable amount of the variation in the sponsorship and cosponsorship choices among the members of Congress that choose to build reputations as disadvantaged groups advocates, but certainly not all. There remain some important differences in these sponsorship and cosponsorship decisions pertaining to disadvantaged groups within each category, particularly for those groups that have the highest and the lowest perceived levels of deservingness of government assistance. I argue that a considerable amount of this variation across groups that would otherwise be considered to be fairly similar in how they are regarded by the American people can be explained by taking a closer look at the ways in which different disadvantaged groups are integrated into the committee structure within the Congress.

6.5.1 Committee Structure and the Choice of Representative Actions

Congressional committees benefit members of Congress in two ways that are particularly relevant for sponsorship and cosponsorship decisions. Committee membership lends a member the presumption of expertise about the topic area, which in turn increases their visibility on related issues. Committees also provide members with access to institutional mechanisms that can increase the likelihood that a member’s preferred policies actually make it into law. These potential benefits of committee membership have differential levels of impact on the decision of how to represent different disadvantaged groups, relative to how a group’s interests map onto the purview of a particular committee.

This possible committee-group interest agreement can fall into three general categories. First, there is an obvious match between group interests and a single committee’s jurisdiction. Second, there may be a readily apparent match between group interests and committee jurisdiction, but it is split between a few specific committees. Or, finally, a group’s interests may not fall clearly under the jurisdiction of any particular committee (or committees). Because the placement of group interests within the committee system can take on such very different forms, it is expected to condition a member’s evaluations of the risk, visibility, and potential passage of any group-specific piece of legislation.

In the first scenario, where group interests clearly map onto the jurisdiction of a single committee, it is expected that committee membership will be quite important in a member’s decisions about the proportion of their bill sponsorship or cosponsorship activity that they are going to devote to that particular disadvantaged group. If a group’s interests clearly match up with a single committee’s jurisdiction, there will be a higher level of competition for attention for legislative actions like bill sponsorship and cosponsorship between members on the committee going about their work, and those outside of the committee who are seeking to advocate on behalf of the group.Footnote 8 This increase in the number of potential group experts (those on the committee as well as those with advocacy reputations) is likely to further drive down the visibility of potential bill sponsorship actions, and decrease the chances that non-committee members would be able to advance bills through the legislature (due to the institutional benefits committee membership provides for advancing bills through the legislative process). Though cosponsorship remains a low effort activity, non-committee members seeking to devote a large portion of their reputation to serving this group may forgo engaging in a high level of cosponsorship of related legislation, as it is perceived to have limited payoff. This is especially likely to be true if the group is broadly considered to be highly deserving of government assistance, because the low levels of risk makes cosponsorship of legislation benefiting such groups appealing to a wider range of members.

For bill sponsorship, the calculus may change further. Sponsoring a single bill, particularly for someone outside the committee, may be sufficient to boost a superficial reputation as a group advocate, but someone wanting to devote a large portion of their reputation to serving this group may prefer other legislative actions with greater potential to draw attention or affect policy outcomes. However, for members seeking to represent groups with mixed or low levels of perceived deservingness who are not already fighting against limited potential visibility, bill sponsorship and cosponsorship may remain attractive tools for reputation building, because the higher levels of potential risk may make such actions less common, and raise visibility.

Considerations are similar for members facing the second scenario, where they are interested in representing groups whose interests fit in well with the jurisdictions of several different committees. Here, again, it is expected that members serving on a committee whose jurisdiction clearly includes specific group interests will devote a larger portion of their sponsorship and cosponsorship activities to legislative action related to that group. That said, because these group interests are spread across multiple committee jurisdictions, the impact on visibility and potential passage is expected to be less severe, though still present. I expect that these diminished impacts will maintain the attractiveness of cosponsorship for all members wishing to be known for representing the group, regardless of their perceived level of deservingness. Because cosponsorship is still considered a viable option for those only wanting to devote a small portion of their reputation to serving a group, bill sponsorship is likely to remain within the purview of those with the strongest reputations for group advocacy.

For members finding themselves in the third scenario, wherein group interests do not clearly map onto the jurisdiction of any specific committee more so than any other, committee membership should not play a significant role in the decision to incorporate disadvantaged-group advocacy into bill sponsorship and cosponsorship decisions. Because visibility, risk, and potential for passage are not likely to be impacted by the committee structure, member decisions are expected to remain in line with the expectations set out by the characteristics of the group, and the actions themselves, rather than jurisdictional factors. As committee membership is not a significant element of the decision-making regarding these groups, other conditions, such as partisanship, may play an increased role.

6.6 Impact of Committee-Group Alignment on Sponsorship and Cosponsorship Decisions

In this final component of the analysis, I reconsider the differences in the choice of legislative actions that members building reputations as advocates of various disadvantaged groups make, after taking into account the particular disadvantaged group’s position within the structure of committee jurisdiction. To do this, I re-evaluate the models introduced above, this time controlling for membership on a committee relevant to a given disadvantaged group. In the remaining sections of the chapter, I explain the formation of the committee membership variable in greater detail, and then analyze the impact of committee membership on the decision to sponsor or cosponsor legislation related to particular disadvantaged groups, first in the House of Representatives, and then in the Senate.

6.6.1 Measuring Committee Membership

Membership on a relevant committee is coded as a dichotomous variable for each group of interest, where a member is either on a potentially related committee or they are not. I also include an indicator variable for members who are the committee chair for a relevant committee.Footnote 9 Committee assignments were obtained from Charles Stewart and Jonathan Woon’s dataset on modern congressional standing committees. Relevant committees were determined by comparing the relevancy of committee and subcommittee jurisdictions to particular groups and group interests.

A member of the House of Representatives is considered to be on a committee with greater potential to handle issues relevant to people in poverty if they are on the Agriculture, Education and Labor, Public Works, or Ways and Means Committees. Committees with jurisdictions potentially the most relevant to women’s concerns are Education and Labor, Commerce, and Judiciary, while concerns of racial and ethnic minorities are likely to be addressed on the Education and Labor and Judiciary Committees. Veterans’ issues are more likely to come before the Armed Services and Veterans’ Affairs Committees, seniors’ issues before Judiciary, Commerce, and Ways and Means, immigrants’ issues before the Judiciary, and issues relevant to Native Americans before Education and Labor and the Natural Resources Committee.Footnote 10 The relevant committee designations are largely similar for members of the Senate, but with Finance Committee members being treated as the equivalent of members of the Ways and Means Committee.

6.6.2 Committee-Group Alignment and Sponsorship and Cosponsorship Activity in the House of Representatives

6.6.2.1 High Committee-Group Alignment

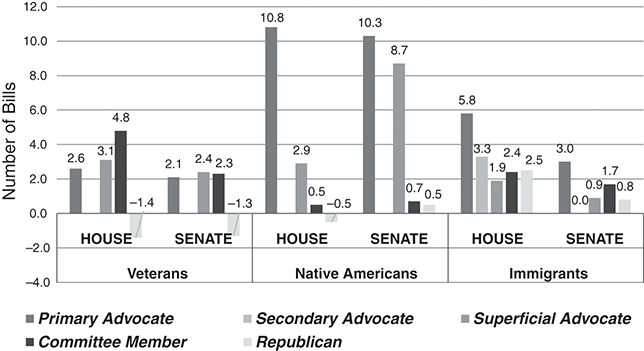

Issues pertaining to veterans, Native Americans, and immigrants are almost entirely dealt with by a single committee – Veterans’ Affairs for veterans, Natural Resources for Native Americans, and Judiciary for immigrants. As a consequence of this, committee membership is expected play a significant role in the percentage of sponsored or cosponsored bills that relate to these groups. The results of the committee analysis for issues pertaining to veterans, Native Americans, and immigrants are found in the first, second, and third columns, respectively, of Tables 6.5 and 6.6.

Table 6.5 Committee membership and the percentage of bills cosponsored across disadvantaged groups in the House

| (1) Veterans | (2) Native Americans | (3) Immigrants | (4) Poor | (5) Race/ Ethnicity | (6) Seniors | (7) Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Advocates | 1.260 | 5.259 | 2.804 | 1.978 | 0.644 | 0.365 | 2.157 |

| 0.981 | 0.236 | 0.354 | 0.185 | 0.072 | 0.157 | 0.256 | |

| Secondary Advocates | – | – | 1.598 | 1.250 | 0.419 | – | 1.166 |

| 0.328 | 0.121 | 0.056 | 0.179 | ||||

| Superficial Advocates | 1.513 | 1.414 | 0.925 | 0.452 | 0.287 | 0.252 | 0.427 |

| 0.207 | 0.182 | 0.228 | 0.086 | 0.048 | 0.102 | 0.134 | |

| Committee Member | 2.318 | 0.233 | 1.175 | 0.196 | 0.071 | −0.083 | −0.047 |

| 0.133 | 0.049 | 0.135 | 0.060 | 0.029 | 0.062 | 0.063 | |

| Committee Chair | −0.666 | 0.365 | −0.161 | 1.788 | −0.274 | 0.042 | 0.499 |

| 1.100 | 0.285 | 0.775 | 0.313 | 0.159 | 0.335 | 0.348 | |

| Cosponsorship Quartile | 0.217 | −0.010 | 0.148 | 0.135 | 0.000 | 0.207 | 0.270 |

| 0.053 | 0.020 | 0.041 | 0.032 | 0.012 | 0.030 | 0.031 | |

| Sponsorship Quartile | 0.025 | 0.041 | −0.047 | −0.049 | −0.002 | −0.014 | −0.016 |

| 0.049 | 0.019 | 0.039 | 0.030 | 0.011 | 0.028 | 0.029 | |

| Republican | −0.694 | −0.254 | 1.188 | −0.836 | −0.185 | −0.107 | −1.434 |

| 0.105 | 0.041 | 0.083 | 0.065 | 0.025 | 0.059 | 0.062 | |

| Leadership | −0.745 | 0.178 | 0.829 | 0.919 | 0.442 | −0.800 | 1.401 |

| 0.495 | 0.191 | 0.387 | 0.297 | 0.112 | 0.279 | 0.291 | |

| Majority | −0.537 | 0.014 | −0.944 | 0.373 | −0.276 | −0.439 | 0.035 |

| 0.101 | 0.039 | 0.079 | 0.061 | 0.023 | 0.057 | 0.060 | |

| First Term | 0.715 | 0.104 | −0.123 | 0.089 | 0.008 | −0.018 | 0.168 |

| 0.135 | 0.052 | 0.105 | 0.081 | 0.031 | 0.076 | 0.079 | |

| Constant | 4.642 | 0.511 | 1.314 | 2.754 | 0.898 | 1.565 | 2.636 |

| 0.214 | 0.082 | 0.167 | 0.129 | 0.048 | 0.120 | 0.125 | |

| N | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 | 2,032 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.419 | 0.308 | 0.221 | 0.316 | 0.276 | 0.126 | 0.391 |

Table 6.6 Committee membership and the percentage of bills sponsored across disadvantaged groups in the House

| (1) Veterans | (2) Native Americans | (3) Immigrants | (4) Poor | (5) Race/ Ethnicity | (6) Seniors | (7) Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Advocates | 3.436 | 17.475 | 7.198 | 4.618 | 2.866 | 1.737 | 8.977 |

| 3.896 | 1.303 | 1.453 | 0.857 | 0.272 | 0.562 | 0.843 | |

| Secondary Advocates | – | – | 8.706 | 3.457 | 0.829 | – | 2.763 |

| 1.321 | 0.566 | 0.212 | 0.589 | ||||

| Superficial Advocates | 5.146 | 8.700 | 1.686 | 0.741 | 0.209 | 0.570 | 1.043 |

| 0.826 | 1.006 | 0.917 | 0.400 | 0.184 | 0.368 | 0.444 | |

| Committee Member | 5.433 | 0.594 | 4.048 | 0.919 | 0.273 | 0.178 | −0.153 |

| 0.529 | 0.270 | 0.548 | 0.278 | 0.109 | 0.224 | 0.209 | |

| Committee Chair | −5.436 | 0.814 | 0.035 | 1.490 | 0.040 | −0.153 | 0.778 |

| 4.368 | 1.576 | 3.124 | 1.450 | 0.600 | 1.197 | 1.145 | |

| Cosponsorship Quartile | −0.048 | 0.076 | 0.094 | 0.341 | −0.082 | 0.216 | 0.271 |

| 0.210 | 0.113 | 0.166 | 0.147 | 0.046 | 0.107 | 0.102 | |

| Sponsorship Quartile | −0.199 | −0.041 | 0.075 | 0.006 | 0.047 | 0.171 | −0.034 |

| 0.196 | 0.106 | 0.156 | 0.137 | 0.042 | 0.101 | 0.097 | |

| Republican | −0.505 | −0.068 | 0.740 | −0.331 | −0.038 | 0.509 | −0.491 |

| 0.419 | 0.225 | 0.334 | 0.302 | 0.093 | 0.213 | 0.205 | |

| Leadership | −1.102 | −0.967 | −0.846 | 6.855 | −0.272 | −0.354 | −0.371 |

| 1.967 | 1.056 | 1.560 | 1.375 | 0.424 | 0.999 | 0.958 | |

| Majority | −0.472 | −0.054 | −0.339 | 0.265 | −0.081 | −0.151 | 0.384 |

| 0.403 | 0.217 | 0.320 | 0.282 | 0.087 | 0.205 | 0.197 | |

| First Term | 1.464 | −0.147 | 0.244 | −0.064 | 0.149 | 0.389 | 0.218 |

| 0.540 | 0.288 | 0.425 | 0.378 | 0.116 | 0.273 | 0.260 | |

| Constant | 5.140 | 0.824 | 0.764 | 2.081 | 0.446 | −0.084 | 0.488 |

| 0.855 | 0.456 | 0.678 | 0.601 | 0.184 | 0.433 | 0.414 | |

| N | 2,015 | 2,015 | 2,015 | 2,015 | 2,015 | 2,015 | 2,015 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.112 | 0.116 | 0.061 | 0.062 | 0.064 | 0.011 | 0.074 |

The cosponsorship of bills relevant to all three of these groups is impacted by partisanship. For bills related to veterans and Native Americans, Democrats are more likely to have a high percentage of cosponsored bills, while sponsorship decisions are made on a non-partisan basis. The sponsorship and cosponsorship of bills impacting immigrants, however, is more common among Republicans. The impact of reputation is also slightly different for bills related to each of these groups. For veterans’ bills, after the significant impact of committee membership is taken into account, only those members with reputations for superficial advocacy are markedly more likely to have higher percentages of sponsorship and cosponsorship.

This lack of a significant effect of reputations for primary advocacy on the sponsorship and cosponsorship of bills related to veterans is not entirely unexpected under the theoretical framework laid out. If the Veterans’ Affairs Committee did not exist, members seeking to advocate for veterans would already be facing a busy representational space with low risk, but low visibility. The presence of committee experts depresses both visibility and the likelihood of the passage of any one bill, meaning that even someone who sponsors a higher percentage of bills related to veterans may not actually stand out. In this circumstance, individuals with a reputation for primary advocacy for veterans may very well prefer to engage in a different representational tactic that has the potential to be higher profile.

For bills pertaining to Native Americans and immigrants, groups with generally mixed levels of perceived deservingness, committee members are significantly more likely to have a higher percentage of bill sponsorship and cosponsorship, but this does not supplant the effects of members having developed a reputation for advocacy. As was seen in Figures 6.1–6.4, though there is some variation, there are generally fewer bill sponsorships or cosponsorships relevant to Native Americans or immigrants than for those groups that are generally considered to have a high level of perceived deservingness of government assistance. This means that any legislative action related to these groups already has a high level of visibility. Thus, even with the competition with specific committee experts for attention when it comes to introducing and cosponsoring bills relevant to Native Americans or immigrants, members with reputations for advocacy still consider both of these actions to be worthwhile.

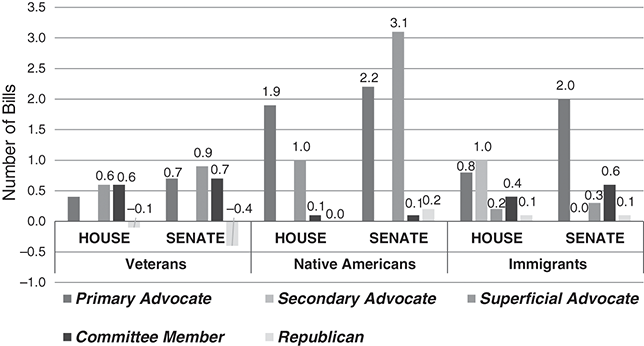

6.6.2.2 Moderate Committee-Group Alignment

Full results of the committee analysis of the interests of racial/ethnic minorities and the poor are seen in columns (4) and (5) of Tables 6.5 and 6.6. Unlike the interests of veterans, Native Americans, and immigrants, bills pertaining to the issues of racial/ethnic minorities and the poor are likely to be addressed by several different specific committees. As an example, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits (formerly food stamps) are handled on the Agriculture Committee, while Pell Grants are the purview of the Education and Labor Committee. Thus, while committee membership does still have a significant impact upon the percentage of bills that a member sponsors or cosponsors that are relevant to their group, it is not as strong an effect as that seen in the previous section. As was the case for members representing most groups with a high level of overlap between committee and group interests, however, partisanship generally plays a significant role only in a member’s cosponsorship decisions, but not sponsorship.

Members with reputations as advocates for each of these groups still consider cosponsorship as a viable way to boost their reputations, even after committee membership is taken into account. This indicates that a member’s risk/reward analysis for this action is still on the side of cosponsorship, despite having some additional competition for attention coming from committee experts. This calculus becomes slightly different for these groups when considering the effects of committee membership and reputation on sponsorship decisions.

In both instances, members with reputations for superficial group advocacy do not have elevated bill sponsorship percentages, though primary and secondary advocates do. Though these results appear to be the same across groups, I expect that there is slightly different reasoning behind it. Potential advocates for racial/ethnic minorities are already facing a higher risk, higher visibility environment. While the presence of other committee experts may alleviate some of that potential visibility, the risk is likely to still be considered too high for those with reputations for only superficial advocacy, and they are content to engage in actions like cosponsorship instead. For those seeking to advocate on behalf the poor, this logic may be inverted. As seen in Figures 6.1 and 6.3, sponsorship and cosponsorship related to the poor is more common than for any of the other groups with mixed levels of perceived deservingness, meaning that the visibility from sponsorship is lower. When paired with the further reduction of visibility and likelihood of passage that comes from competing with committee experts, superficial advocates likely evaluate the bill sponsorship to be not worth the increased efforts, while secondary and primary advocates remain willing to try.

6.6.2.3 Low Committee-Group Alignment

The interests pertaining to the final two groups, women and seniors, do not have as clear a home within the committee system. As a result of this, membership on particular committees is not a driving force behind sponsorship and cosponsorship decisions, as seen in columns (6) and (7) of Tables 6.5 and 6.6. Rather, the choice to sponsor or cosponsor bills related to these groups stand out for a different reason – the persistent effects of partisanship. The lack of a clear committee match increases the partisan considerations for bill sponsorship, but not in the same direction. Republicans remain more likely to sponsor a higher percentage of bills related to seniors, while bills pertaining to women’s interests make up a higher proportion of sponsorship activity for Democrats. These results follow in line with the theoretical expectations, whereby representational decisions for these groups are conditioned by group perceptions, but not by committee membership.

6.6.3 Committee-Group Alignment and Sponsorship and Cosponsorship Activity in the Senate

6.6.3.1 High Committee-Group Alignment

The dynamics of sponsorship and cosponsorship in the Senate differ in important ways from those of the House, as seen in Tables 6.7 and 6.8. In the House, membership on one of the committees with clear jurisdiction over the issues pertaining to veterans, immigrants, and Native Americans is significantly related to relevant sponsorship and cosponsorship activity. But while this is true for immigrants’ and veterans’ bills in the Senate, the same cannot be said for legislation addressing concerns of Native Americans. This implies that even with clear committee jurisdiction, senators still have a wide range of latitude over the issues they cover. Particularly in the modern Senate, in which the former Indian Affairs Committee has been eliminated and its jurisdiction rolled into the Resources Committee, senators have a great deal of leeway when deciding which of the issues fitting under the umbrella of Resources they want to work on. Thus, given the status of Native Americans as a group about which the broader American public tends to have more mixed perceptions, senators who are not intentionally seeking to form a reputation as a Native American advocate are unlikely to pursue legislation on their behalf, even if they sit on the committee that would most readily facilitate such actions.

Table 6.7 Committee membership and the percentage of bills cosponsored across disadvantaged groups in the Senate

| (1) Veterans | (2) Native Americans | (3) Immigrants | (4) Poor | (5) Race/ Ethnicity | (6) Seniors | (7) Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prim/Sec Advocates | 1.260 | 6.188 | 1.804 | 0.906 | −0.069 | 0.675 | 1.375 |

| 0.549 | 0.580 | 0.610 | 0.246 | 0.163 | 0.223 | 0.290 | |

| Superficial Advocates | 1.447 | 5.214 | 0.561 | 0.697 | 0.055 | 0.366 | 0.773 |

| 0.380 | 0.653 | 0.341 | 0.179 | 0.119 | 0.152 | 0.227 | |

| Committee Member | 1.365 | 0.389 | 1.026 | 0.407 | 0.069 | 0.067 | 0.136 |

| 0.192 | 0.199 | 0.191 | 0.133 | 0.043 | 0.094 | 0.131 | |

| Committee Chair | 1.223 | 0.223 | 0.050 | 1.083 | 0.072 | 0.013 | 0.521 |

| 0.637 | 0.735 | 0.726 | 0.387 | 0.147 | 0.290 | 0.382 | |

| Cosponsorship Quartile | 0.178 | −0.155 | −0.166 | 0.155 | −0.032 | 0.373 | −0.072 |

| 0.107 | 0.119 | 0.088 | 0.078 | 0.025 | 0.056 | 0.079 | |

| Sponsorship Quartile | 0.127 | 0.307 | 0.021 | 0.043 | 0.014 | −0.171 | −0.081 |

| 0.103 | 0.115 | 0.085 | 0.075 | 0.024 | 0.055 | 0.077 | |

| Republican | −0.786 | 0.280 | 0.463 | −1.407 | −0.017 | −0.458 | −1.643 |

| 0.182 | 0.201 | 0.149 | 0.135 | 0.042 | 0.096 | 0.134 | |

| Leadership | 0.496 | 0.156 | −0.439 | 0.026 | 0.280 | −0.228 | −0.405 |

| 0.434 | 0.479 | 0.358 | 0.313 | 0.101 | 0.226 | 0.316 | |

| Majority | −0.029 | 0.143 | −0.274 | −0.447 | −0.022 | 0.114 | 0.213 |

| 0.185 | 0.204 | 0.152 | 0.136 | 0.043 | 0.098 | 0.137 | |

| First Term | 0.213 | −0.216 | 0.070 | 0.535 | −0.014 | −1.127 | 0.270 |

| 0.263 | 0.289 | 0.216 | 0.191 | 0.061 | 0.137 | 0.194 | |

| Constant | 3.556 | 0.194 | 1.494 | 2.150 | 0.468 | 0.632 | 4.080 |

| 0.384 | 0.416 | 0.305 | 0.277 | 0.087 | 0.198 | 0.277 | |

| N | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 | 494 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.399 | 0.296 | 0.169 | 0.331 | 0.130 | 0.327 | 0.375 |

Table 6.8 Committee membership and the percentage of bills sponsored across disadvantaged groups in the Senate

| (1) Veterans | (2) Native Americans | (3) Immigrants | (4) Poor | (5) Race/ Ethnicity | (6) Seniors | (7) Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prim/Sec Advocates | 2.913 | 8.585 | 8.061 | 1.853 | −0.153 | 1.240 | 3.034 |

| 1.689 | 1.279 | 1.560 | 0.720 | 0.317 | 0.627 | 0.687 | |

| Superficial Advocates | 3.766 | 12.402 | 1.049 | 0.790 | 0.482 | 0.685 | 0.781 |

| 1.169 | 1.440 | 0.872 | 0.524 | 0.230 | 0.427 | 0.537 | |

| Committee Member | 2.882 | 0.377 | 2.567 | 1.518 | 0.131 | 0.189 | 0.568 |

| 0.593 | 0.440 | 0.492 | 0.392 | 0.084 | 0.265 | 0.311 | |

| Committee Chair | 8.300 | 0.144 | −0.178 | 2.497 | −0.083 | −0.439 | 1.306 |

| 1.959 | 1.621 | 1.857 | 1.046 | 0.286 | 0.818 | 0.905 | |

| Cosponsorship Quartile | 0.018 | −0.189 | 0.211 | −0.190 | −0.072 | 0.431 | −0.250 |

| 0.331 | 0.263 | 0.226 | 0.230 | 0.049 | 0.159 | 0.189 | |

| Sponsorship Quartile | 0.030 | 0.273 | −0.412 | 0.049 | 0.101 | −0.276 | −0.195 |

| 0.317 | 0.254 | 0.218 | 0.221 | 0.047 | 0.156 | 0.181 | |

| Republican | −1.433 | 0.850 | 0.457 | −0.673 | −0.017 | 0.240 | −0.963 |

| 0.560 | 0.444 | 0.382 | 0.394 | 0.082 | 0.271 | 0.317 | |

| Leadership | 0.775 | −0.672 | 1.623 | −0.552 | −0.267 | −0.703 | −0.807 |

| 1.336 | 1.057 | 0.915 | 0.918 | 0.196 | 0.637 | 0.750 | |

| Majority | −0.660 | 0.007 | −0.355 | −0.667 | −0.031 | 0.493 | 0.341 |

| 0.569 | 0.450 | 0.389 | 0.398 | 0.084 | 0.275 | 0.325 | |

| First Term | 1.676 | −0.318 | 0.456 | 0.149 | −0.077 | −0.997 | 0.238 |

| 0.812 | 0.639 | 0.554 | 0.561 | 0.119 | 0.388 | 0.461 | |

| Constant | 4.349 | 1.160 | 1.141 | 2.218 | 0.296 | 0.041 | 2.849 |

| 1.187 | 0.925 | 0.785 | 0.819 | 0.170 | 0.561 | 0.661 | |

| N | 492 | 492 | 492 | 492 | 492 | 492 | 492 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.180 | 0.185 | 0.125 | 0.074 | 0.015 | 0.024 | 0.073 |

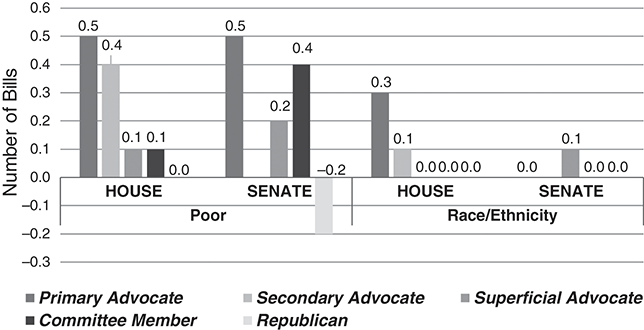

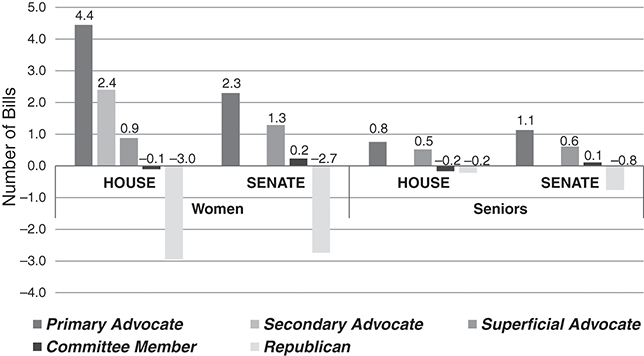

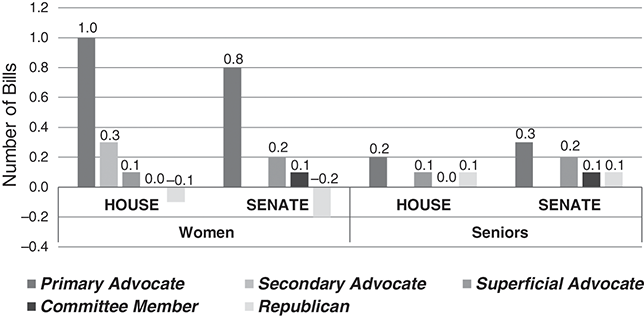

In the House, members with reputations for superficial advocacy of veterans were significantly more likely to cosponsor or sponsor bills related to veterans’ issues, but those with primary/secondary reputations were not. This was not unexpected, as the size of the House makes it much less likely that any singular action on behalf of a well-regarded group would be highly visible, particularly when there is a clear alignment between committee jurisdiction and group interests. In the Senate, the inherently increased visibility makes cosponsorship appealing for senators with reputations for any level of veterans’ advocacy, but sponsorship is only used as a tool to maintain reputations for superficial advocacy, as the smaller number of actors within the chamber only goes so far to mitigate the effects of having to compete with committee experts as well. Conversely, senators maintaining reputations as primary or secondary advocates of immigrants are significantly more likely to use sponsorship and cosponsorship to bolster their reputations, likely reflecting the smaller pool of competitors for immigrant advocates compared to a highly regarded group like veterans. Senators with reputations at all levels of advocacy for Native Americans are markedly more likely to dedicate higher percentages of their sponsorship and cosponsorship activity to the group. The magnitude of these effects can be seen in Figures 6.5 and 6.6.