Both the numbers of international courtsFootnote 1 and their judgments increased markedly throughout the 1990s and the early 2000s (Alter Reference Alter2014). More recently, however, these institutions have faced a growing backlash (Alter, Gathii, and Helfer 2016a; Sandholtz, Bei, and Caldwell Reference Sandholtz, Bei and Caldwell2017; Madsen, Cebulak, and Wiebusch Reference Madsen, Cebulak and Wiebusch2018). Several states have rescinded the jurisdiction of international human rights courts. Others are trying to limit Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) by renegotiating or canceling Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs). Moreover, governments have undertaken efforts to constrain international judicial bodies through institutional reforms and by blocking judicial appointments.

What explains these backlashes? The simplest answer is that governments have tired of international courts imposing costly judgments. Yet many governments continue to accept consequential adverse rulings. Other governments have rejected individual rulings without challenging the authority of international courts. Moreover, the rulings that trigger backlashes sometimes have relatively low material implementation costs.

I argue that many, though not all, backlashes against international courts have taken place in countries where governments rely on populist support and over court judgments that reinforce local populist mobilization. Populism comes in many varieties. Yet a commonality among populists is that politics should be an expression of the will of the “pure people” as opposed to “corrupt elites” (e.g., Canovan Reference Canovan1999; Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Moreover, populists typically distinguish the pure people from specific others, which can be immigrants, ethnic or racial minorities, criminals, or some other group that is singled out as undeserving in a specific national context.

The rulings of international courts with liberal mandates sometimes protect the groups who are the targets of populist ire. Investment tribunals, regional economic courts, and even human rights courts protect property rights, which often favor ruling elites or foreign investors. Human rights courts evaluate large numbers of claims from prisoners, immigrants, and other minority groups who may be the target of populist identity politics. International courts become salient when they deliver judgments that protect elites or minorities against whom there is a pre-existing populist mobilization. In other words, international court judgments can provide kindling to already burning populist fires. Yet this tells us only that international courts may become controversial in countries with strong populist movements. Populism also offers an ideology for why these international courts should not have authority in the first place. International courts, like domestic courts, are countermajoritarian institutions. Moreover, they are located outside the homeland. Strong populist movements or populist presidents make it more likely that governments opt for challenging the authority of courts over alternative strategies such as acceptance, non-compliance, or avoidance.

This argument implies that backlashes against international courts are not just about sovereignty. Populist attacks on international courts often closely track efforts to curb domestic courts. Moreover, leaders may instigate backlashes to attract popular support. By contrast, much of the literature assumes that the public constrains leaders from violating international law and that international courts serve as substitutes for poorly functioning domestic courts. Some political parties, media, and civil society groups do not see international courts as tools to protect them from the illiberal tendencies of elites but as tools for liberal elites to cement their preferred policies against the “will of the people.”

I proceed with an explanation of what the backlash against international courts is and I identify twenty-eight backlashes that targeted the formal authority of international courts. I then evaluate two explanations derived from existing theories: a cost-benefits argument and an account that links legalization to democratization and thus the backlash to the reverse of democratization. I then explain the theoretical links between populism and the backlash against international courts. The next section establishes the descriptive claim that a large percentage of backlashes are indeed started by leaders widely identified as populists in the literature. I offer narrative evidence that backlash episodes were often about property rights or minorities who were the subject of pre-existing domestic populist mobilization, that leaders used populist rhetoric to undermine a court’s authority, and that populist backlashes against international courts often coincide with backlashes against domestic courts over similar issues. The conclusion discusses the implications for the international legal system and for the study of international institutions. Populism is too thin an ideology as a basis for forming coalitions for effectively reforming international courts. Selective exit is a more common outcome. More generally, there is much to be gained from jointly engaging the burgeoning literatures on populism in comparative politics and on backlashes in international law.

What Are Backlashes against International Courts?

Scholars have used the term backlash to describe resistance against investment arbitration (Waibel Reference Waibel, Kaushal, Chung and Balchin2010; Caron and Shirlow Reference Caron and Shirlow.2016); NAFTA dispute settlement (Krueger Reference Krueger2003); the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) (Alter Reference Alter2000); international human rights courts (Sandholtz, Bei, and Caldwell Reference Sandholtz, Bei and Caldwell2017); the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) (Madsen Reference Madsen2016); the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) (Helfer Reference Helfer2002); African regional courts (Alter, Gathii, and Helfer Reference Alter, Gathii and Helfer2016a); and the International Criminal Court (ICC) (Helfer and Showalter 2017). There is a good deal of consistency in how scholars use the term. A backlash refers to government actions that aim to curb or reverse the authority of an international court. Although a court decision may trigger a backlash, a backlash ultimately targets the court rather than just the ruling. Backlash differs from non-compliance or partial compliance (Hawkins and Jacoby 2010; Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014), even if systematic non-compliance could undermine the court’s authority.

Despite consistency in the overall definition of a backlash, there has not been a systematic effort to operationalize the concept. I offer an operationalization here. A first type of backlash targets a court’s general authority. For example, Zimbabwe succeeded in eliminating the Southern African Development Community (SADC) tribunal (Alter, Gathii, and Helfer Reference Alter, Gathii and Helfer2016a). The United States may be in the process of accomplishing the same thing using the same tactic by vetoing new appointments to the World Trade Organizations’ (WTO) Appellate Body (AB) (Shaffer, Elsig, and Pollack Reference Shaffer, Elsig and Pollack2017). This category also includes reform attempts that had the clear objective to curb a court’s authority, even if these did not succeed. I only consider instances where governments introduce concrete reform proposals. For example, the United Kingdom used its Council of Europe chairmanship to propose reforms whose clear objective was to limit the ECtHR’s authority (Helfer Reference Helfer2012).

A second type of backlash applies only to a court’s authority over an individual country. Governments do not always have the option to eliminate a court altogether but they can typically extract themselves from a court’s jurisdiction. For example, Venezuela pulled out of the IACtHR, Rwanda withdrew its declaration granting its citizens access to the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), and Burundi has left the ICC. Bolivia, Ecuador, Indonesia, Poland, South Africa, and Venezuela have sought to withdraw themselves from investment arbitration where possible (Peinhardt and Wellhausen Reference Peinhardt and Wellhausen2016). I also include instances where governments have made explicit and credible threats to exit even if they haven’t (yet) followed through. For example, South Africa’s High Court blocked South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma’s attempt to withdraw from the ICC. Similarly, British Prime Minister Theresa May has stated repeatedly that the UK should leave the ECtHR and the Conservative Party endorsed this policy in its party manifesto.Footnote 2

This operationalization focuses on efforts to curb a court’s formal institutional authority. There are other ways that governments may threaten a court’s authority. This includes broad critiques that seek to delegitimize a court but that fall short of threatening exit. Including such critiques may introduce bias if critical speeches by populists draw more attention. For example, a speech by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban on the ECtHR may draw more publicity because there is a pre-existing concern about the Hungarian government’s commitment to human rights. Moreover, it is difficult to draw the line regarding which criticisms do and do not threaten a court’s authority. It also excludes temporary suspensions due to declared emergencies, such as the Turkish suspension of the European Convention on Human Rights in 2016 under populist President Tayyip Erdogan. I also only focus on backlashes by members of a court, thus excluding the recent backlash by the Trump administration against the ICC. The theory may well apply to such instances but I limit the focus of the empirical examination to formal institutional authority.

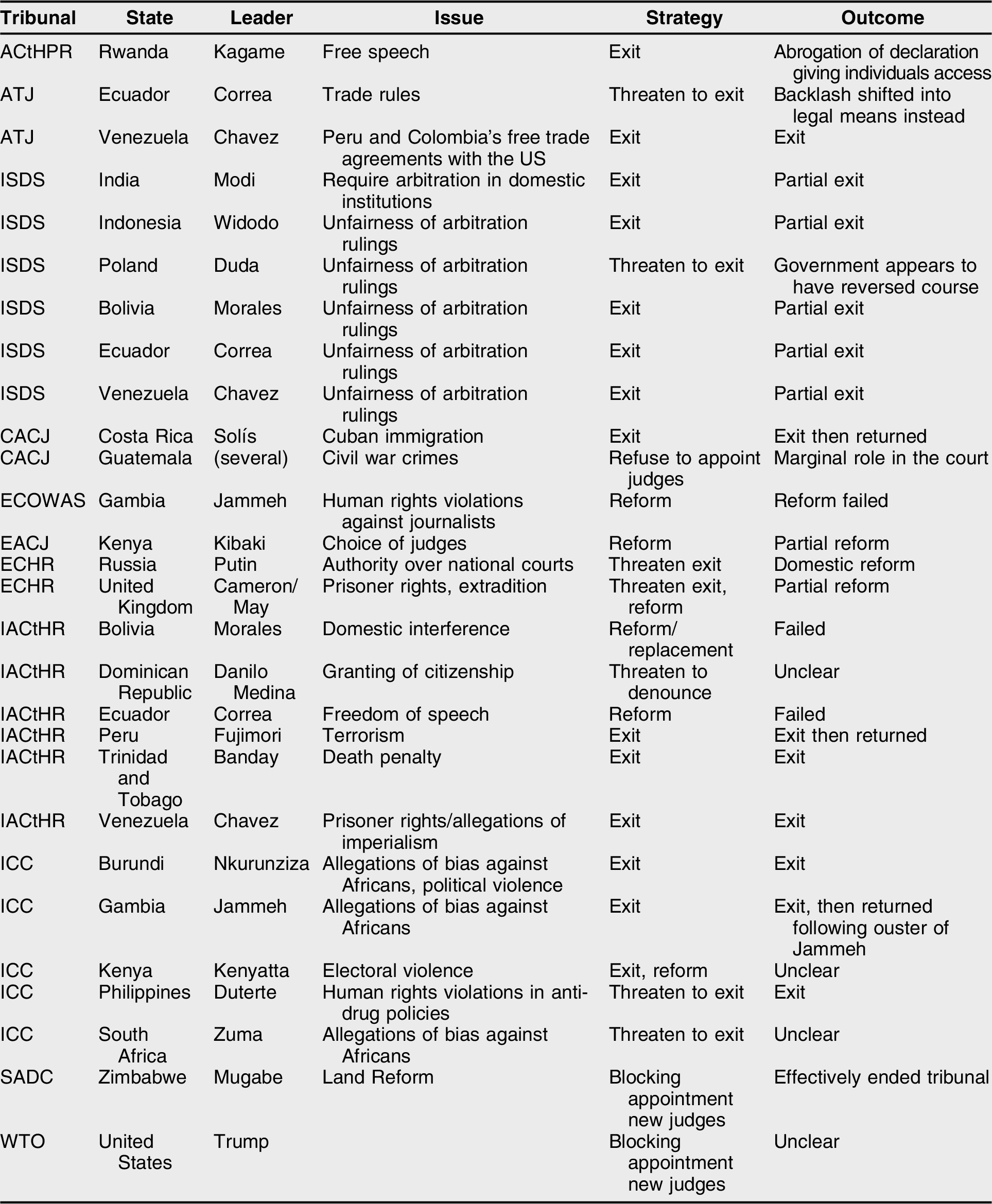

Table 1 identifies twenty-eight episodes of backlash against eleven different international judicial institutions. The table is based on an extensive search of the secondary literature. Online appendix A includes more details and references. The table lists countries from all continents (other than Australia) and it includes of the world’s most powerful states as well as some of the smaller states. This list aims to be exhaustive given the limits defined here. Yet both the literature and events are evolving rapidly so it is possible that the list excludes some episodes that would qualify.

Table 1 Backlashes against international courts since 1990.

Explanations for Backlash

While there is a growing literature on backlashes against international courts, this literature has not yet developed a general theory of why backlashes occur. Some of the literature focuses on explaining the success or failure of backlash attempts (Alter, Gathii, and Helfer Reference Alter, Gathii and Helfer2016b; Alter and Helfer 2017b), the implications for international courts (Helfer Reference Helfer2018) and legal academia (Posner Reference Posner2017), and on mapping backlashes (Madsen, Cebulak, and Wiebusch Reference Madsen, Cebulak and Wiebusch2018). Other scholars develop explanations for backlashes in specific contexts (Sandholtz, Bei, and Caldwell Reference Sandholtz, Bei and Caldwell2017; Alter, Gathii, and Helfer Reference Alter, Gathii and Helfer2016b). There are good reasons to do so. Opposition to investment dispute settlement and human rights courts likely has diverse causes. There is no reason to presume that the IACtHR and ECtHR are under scrutiny for the precise same reasons. That said, we might draw some interesting theoretical lessons from examining backlash as a general phenomenon in the same way that legalization and delegation to international courts have been studied in general ways (e.g., Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Kahler, Keohane and Slaughter2000). I draw on the legalization literature to propose two plausible political science theories of backlash: rising implementation costs and a reversal in democratization.

Implementation Costs

The first, and most obvious, theory links backlash to the rising number of binding international court judgments. Governments should be more likely to trigger backlashes when the cumulative implementation costs increase so much that they exceed the benefits of staying inside the regime (Sandholtz, Bei, and Caldwell Reference Sandholtz, Bei and Caldwell2017; Abebe and Ginsburg 2018). It would seem perfectly rational for Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela to limit their exposure to ISDS following large financial awards against them. Indeed, there is evidence that states are more likely to renegotiate BITs when there have been more ISDS awards against them (Haftel and Thompson 2017).

A court “going too far” in the eyes of the target government sometimes triggers backlashes. For example, Russia had minimally implemented ECtHR rulings for decades; paying monetary compensation but not changing policies to prevent future violations (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014). This changed following a judgment that awarded 2,5 billion dollars to Yukos shareholders.Footnote 3 The Putin government responded with a new law that grants Russian courts the right to decide whether Russia needs to implement ECtHR judgments.Footnote 4 Not surprisingly, the Russian courts found that there is no reason for Russia to comply with the Yukos ruling (Netesova Reference Netesova and Taussig2017). Yet even in the Russian case, the ECtHR became controversial with the publicity over an identity ruling—the 2012 Markin ruling, which stated that military servicemen cannot be refused parental leave when such leave is available to servicewomen (Mälksoo and Benedek Reference Mälksoo and Wolfgang2017).

The cost of implementing judgments surely plays a role in backlash. Yet this theory does not explain why some countries do not engage in backlash when faced with high cost judgments, why some backlashes are triggered over judgments that are not that costly to implement, and why some of the highest stakes judgments have not triggered backlashes. For example, many states (e.g., Mexico) with large ICSID awards stay in the system. Some countries, like China and Germany, have responded to adverse rulings by strengthening investor protections rather than resisting the system (Haftel and Thompson 2017). Italy has had more than twice as many ECtHR judgments against it as the United Kingdom without threatening exit. In the UK, relatively easy to implement judgments on prisoner voting rights and extradition spurred a backlash while earlier judgments on Northern Ireland or homosexuals in the military did not (McNulty, Watson, and Philo Reference McNulty, Watson and Philo2014).

One answer is that implementation costs are not just material but also political (Sandholtz, Bei, and Caldwell Reference Sandholtz, Bei and Caldwell2017). This is surely accurate. However, any theory that makes such a claim must specify why some judgments at some times in some countries are politically costly. Without such a theory, the argument becomes circular. We only observe high political costs when politicians vent their rage about a judgment or a court. The proposed link between domestic populist mobilization and international court backlashes is partially an argument about when judgments are more likely to become so controversial that they might trigger backlashes.

Democratization

Theorists have long linked the growing importance of international courts and law in investment, trade, and human rights to democratization (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000; Simmons Reference Simmons2009; Simmons and Danner 2010; Mansfield, Milner, and Rosendorff Reference Mansfield, Milner and Peter Rosendorff2002; Jandhyala, Henisz, and Mansfield Reference Jandhyala, Henisz and Mansfield2011). These theories typically posit that international courts help address a time inconsistency problem. Governments sometimes have incentives to promise that they will improve human rights, respect property rights, prosecute war criminals, and adhere to the provisions of trade agreements. Yet they may also have incentives to violate those promises later. Democratizing states have strong incentives to make credible commitments to international human rights and to “lock-in” democracy (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000). Many democratizing states in the 1990s were also transitioning to market economies. These states often did not have strong property rights protections and they needed foreign investment. This provided incentives to sign BITs and commit to ISDS (Jandhyala, Henisz, and Mansfield Reference Jandhyala, Henisz and Mansfield2011).

If democracy and democratization were responsible for commitments to international courts, then more recent democratic reversals may be responsible for backlash. Populism is often associated with a backlash against liberal democracy. To some extent, the arguments thus overlap. Yet the credible commitment logic assumes that deviating from international court judgments should be politically unpopular. The presumption is that civil society and public opinion mobilize on behalf of international law rather than against it (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). International courts are supposed to protect a democratic public from the kleptocratic tendencies of elites. If leaders could gain electorally from defying international courts, then a commitment to them does not make reform promises more credible.

Moreover, democratization theories assume that international courts are a substitute for poorly functioning domestic courts. Countries with well-functioning domestic legal systems have fewer problems committing to protect investor and human rights. Thus, countries with middling domestic legal institutions have most to gain from committing to international courts (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000; Simmons and Danner 2010). By contrast, the populism argument posits that backlashes against domestic and international courts often go hand in hand.

If governments lose an interest in liberalization, then they also have incentives to withdraw from human rights courts and investment treaties. Yet this is an ideological rather than an institutional explanation. If illiberal leaders come to power, then their interest in commitments to international liberal institutions should decrease even if a country still is an electoral democracy. This suggests a (potentially) democratic but illiberal logic of backlash to international courts.

Populism and the International Judiciary

The argument proceeds in two steps. First, populists often identify themselves as involved in a struggle with groups that international courts with liberal mandates are set up to protect. International courts will sometimes come down with rulings that populists can use to mobilize support. Opposing these court rulings can be a source of popularity for leaders who rely on populist mobilization. Second, populism offers an ideology to challenge the authority of a court rather than just the ruling. From a populist perspective, international courts fail to reflect the vox populi both because these institutions are international and because they are countermajoritarian courts.

These two claims operate together. International courts only become salient after rulings that fuel pre-existing populist mobilization. Without an ideology to challenge the legitimacy of the institution, leaders could challenge a ruling narrowly or refuse to comply. Before substantiating both parts of this argument in more detail, I first discuss the definition of populism.

What Is Populism?

There is an emerging convergence in the literature on Cas Mudde’s definition of populism as a thin-centered “ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004, 543).

This thin-centered ideology creates some commonalities among populist leaders. But these leaders are also diverse in their thicker ideologies. Melvin Hinich and Michael Munger argue that political ideologies have implications for: “(a) what is ethically good, and (therefore) what is bad; (b) how society’s resources should be distributed; and (c) where power appropriately resides” (Hinich and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger1996, 11). Populism as a thin ideology is clearest about the third part: the people should rule. Or, as Margaret Canovan puts it: “Populists claim legitimacy on the grounds that they speak for the people” (Canovan Reference Canovan1999, 12).

Populists define themselves in opposition to a corrupt elite on both distribution and virtue but they differ in just how they do so. For example, Latin American populist presidents of the last two decades have included those who have advocated for more market-oriented (neoliberal) policies, such as Peru’s Alberto Fujimori and Argentina’s Carlos Menem (Weyland Reference Weyland1999; Roberts Reference Roberts1995). These populists attack special interests, such as organized labor or corporatist interests, that prevent deserving people from succeeding. They tend to succeed in inflationary crises when more left-wing policies seem less attractive (Weyland Reference Weyland1999). But Latin American populists have also included leftist politicians like Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, Bolivia’s Evo Morales, and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa who have mobilized around their opposition to neoliberalism and neoimperialism (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012). Despite their differences on socio-economic policy, these leaders are united by claims that they were fighting corrupt elites on behalf of the people.

Populists also frequently accuse elites for pushing dominant values of tolerance that repress a silent majority. Just who does and does not belong to “the virtuous people” again depends on the domestic mobilization narrative (Müller Reference Müller2016). Some populists adopt a full-on nativist ideology. Populists have also used race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and other categories as criteria of exclusion. Identity plays a role in most populist movements, although Latin American populism has typically focused more on the material (distributional) side whereas European populism leans towards a heavier focus on identity (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013).

Why (International) Court Rulings Sometimes Upset Populists

International courts are part of the liberal international institutional order. The texts that international courts interpret typically advance core liberal objectives such as increasing civil liberties, advancing the functioning of domestic markets, and promoting the flow of goods, capital, and people across borders. In interpreting their legal texts, international courts often come down with judgments that clash with populist mobilization around property and minority rights. Populists do not necessarily dismiss the ideas of property or minority rights. Instead, populists object to court judgments that interfere with domestic populist narratives about whose rights deserve to be protected. As Jan-Werner Müller warns, populists are not necessarily against institutions, just those that “in their view, fail to produce the morally (as opposed to empirically) correct political outcomes.”Footnote 5

Property rights are a major preoccupation of international judicial institutions. Most obviously, the purpose of investment treaties is to protect foreign investors from expropriation and other government actions that devalue the investment but violate existing treaties or contracts, even if such actions are popular with majorities (Pelc Reference Pelc2017). Property rights cases (Protocol 1, article 1) are the second most common kind of ECtHR case and regularly feature in the IACtHR. The Andean tribunal primarily resolves intellectual property rights cases (Alter and Helfer 2010). Regional economic courts also have large caseloads concerning the protection of property rights.

Distributive conflict over ownership of natural resources, land, and other wealth is central to populist mobilization in many countries. Property rights is a liberal principle but it can also be conservative: it protects those who already own property. Populists have argued that expropriation can be legitimate if the initial acquisition of property by corrupt elites was unjust. For example, many populist movements in Africa have mobilized around inequity in land rights, often in response to heritages from colonial times (Boone Reference Boone2009). In Latin America, left-wing populists have mobilized in opposition to historical inequities in ownership of media, natural resources, companies, and land, as well as multinational corporations (French Reference French2009).

The idea that elites should create international courts to protect them from majoritarianism is not new. Friedrich von Hayek wrote in the final chapter of the Road to Serfdom that:

An international authority which effectively limits the powers of the state over the individual will be one of the best safeguards of peace. The International Rule of Law must become a safeguard as much against the tyranny of the state against the individual as against the tyranny of the new super-state over the national communities (Hayek Reference Hayek1994, 235).

In the 1950s, French and British leaders on the right, most notably Winston Churchill, actively campaigned for a strong ECtHR and the inclusion of a Protocol on property rights out of fear that future left-wing majorities would expropriate the wealthy (Duranti Reference Duranti2017). As historian Marco Duranti puts it, the ECtHR became “a mechanism for realizing what Socialists described as a discredited conservative agenda too unpopular to be enacted through democratic means” (Duranti Reference Duranti2017, 7). This presents an alternate view of the ECtHR not as an attempt to lock in democracy (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000) but to lock in the interests of elites.

Liberalism demands that individuals have a core set of civil liberties that states have an obligation not to infringe upon (negative rights) or even an active duty to guarantee (positive rights) (Elster Reference Elster1992). The rise of judicial review and the inclusion of human rights in constitutions and international law have contributed to a trend where courts, including international courts, are increasingly asked to offer judgments on what Ran Hirschl calls issues of mega-politics: “core political controversies that define the boundaries of the collective or cut through the heart of entire nations” (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2008, 5). Examples are judicial interference over the outcome of elections or alleged misbehavior by leaders, judicial scrutiny of core executive prerogatives in fiscal policy, foreign affairs, and national security, and, especially, cases that are about the definition of the polity, such as cases that impinge on citizenship, the status of religion or other aspects of identity. Hirschl argues that judicial involvement on such politically charged issues “make the democratic credentials of judicial review most questionable” (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2008, 6).

International courts take part in this trend. The ICC makes judgments about whether sitting presidents have committed criminal offenses. Regional human rights courts have issued judgments about citizenship, religion, immigration, and other issues that directly concern the identity of polities. The CJEU and African regional economic courts have also issued controversial rulings on civil liberties protecting women, LGBT individuals, ethnic minorities, and other vulnerable groups (Cichowski Reference Cichowski2004; Alter, Helfer, and McAllister Reference Alter, Helfer and McAllister2013). Investment tribunals do not just evaluate straight expropriation but increasingly evaluate regulations and policies of democratically elected governments, including identity-related issues such as the habitat of indigenous peoples (Pelc Reference Pelc2017).

My argument is not that all judgments on minority rights activate populist opposition but only those judgments that fit with pre-existing domestic mobilization narratives around these mega-politics identity questions. Indeed, controversy often arises over the very same issues with domestic courts. For example, in the UK populist movements center on excluding certain groups of immigrants and criminals from the virtuous people. I will show later that populists were already mobilizing in opposition to British courts that ruled in favor of prisoner or immigrant rights before they shifted their attention to the ECtHR. By contrast, rulings on LGBT rights did not generate a backlash as there was no populist mobilization targeting LGBT people.

International courts are not always maximally liberal in their interpretations. Indeed, international courts have developed interpretive strategies that allow them to proceed with restraint. For example, investor/state arbitral tribunals have adapted the ECtHR’s margin of appreciation doctrine to allow democratic states leeway in how they respect property and minority rights (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2016). Investors lose many cases where they claim that regulatory actions by democratically elected governments have harmed the value of their investments (Pelc Reference Pelc2017). Yet international courts are often in a position where they have to decide whether a domestically unpopular minority deserves protection by international law. Many of these cases impinge on some aspect of a polity’s identity. In this sense the “judicialization of politics”(Stone Sweet and Brunell Reference Stone Sweet and Brunell2013) almost inevitably spurs a politicization of the judiciary (Ferejohn Reference Ferejohn2002).

Populism and Resistance to the Authority of International Courts

It is not sufficient that international courts sometimes issue controversial rulings. Governments have responded to adverse rulings through non-compliance, partial compliance, and reluctant compliance (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014; Hawkins and Jacoby 2010). We also need to understand why governments sometimes escalate unhappiness about a ruling (or series of rulings) to backlash.

One explanation, as alluded to before, is that some rulings are simply so costly that exit or other forms of backlash become more attractive. This is certainly part of the story. However, I also suggest a different rationale: populism offers an ideology that opposes the very idea that an international court should have authority over issues of distribution, identity, or other matters that fall within the normal provenance of democratic politics.Footnote 6 Populist leaders may benefit electorally from attacking the institutional system rather than just the rulings.

Cas Mudde has described populism as an “illiberal democratic response to undemocratic liberalism” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Illiberal here does not mean opposition to markets or liberal values per se but to the non-majoritarian elements of liberalism. Courts, including international courts, play a role in protecting individuals from “the tyranny of the majority” (e.g., Elster Reference Elster1992). As stated before, a commonality among populists is that politics should be an expression of the vox populi, which is not tyrannical. This allows populists to challenge the decisions of countermajoritarian institutions not just as wrong but also as illegitimate. Both left- and right-wing populist leaders have eroded judicial independence in Latin America (Houle and Kenny Reference Houle and Kenny2018). The Polish and Hungarian governments have reconfigured their highest courts and limited judicial independence (Bugaric and Kuhelj Reference Bugaric and Kuhelj2018). By contrast, it is not always clear that populism undermines other aspects of liberal democracy. For example, there is a lively debate among populism scholars on whether elections with populist parties increase voter turnout (Huber and Ruth Reference Huber and Ruth.2017).

The international character of courts matters in two ways. First, it offers an additional ground for populist leaders to attack the authority of an institution based on sovereignty or identity. It is much easier to challenge an institution as unrepresentative of the will of the people if the judges are foreign and take decisions in foreign locales.

Second, in many instances governments do not have the same means to influence international courts. Domestic courts can be stacked with like-minded judges. It is not as easy to stack international courts. In some instances, a government can effectively kill a court if they have the right to veto new appointments. More typically, reforming an international court requires a multilateral coalition. Given diverse thicker sources of ideological mobilization, it can be difficult to amass successful coalitions for populist leaders. Indeed, the empirical illustrations show that populist-inspired reform attempts have at best had modest influence. This illustrates the limits of populism in a multilateral context. It also makes exit a more likely strategy. However, populists do not always follow up on exit threats. Populists may have domestic incentives to issue exit threats but there could be international benefits to stay within a regime. This again points to the need to consider backlash as a strategy rather than an outcome.

Empirical Evidence

The proposed theoretical link between populism and backlashes against international courts has a range of observable implications. Governments that rely strongly on populist mobilization should be more likely to initiate backlashes. The trigger should be judgments that directly map onto domestic populist mobilization narratives over identity or the distribution of property. Populist backlashes should highlight that an international court is undeserving of its authority, which properly belongs to the people. Backlashes against international courts should go hand in hand with efforts to curtail domestic courts. Individual-level opposition to international courts should be correlated with individual-level opposition to domestic courts (Voeten Reference Voeten2013). Domestic public opinion should not be a constraint but an incentive for attacks on the court by populist leaders. Attacks on the authority of international courts should be especially popular among the supporters of populist leaders or parties.

It is impossible to test all these implications in a single article. They cover different levels of analysis, variation in occurrences of (as well as motivations for) backlashes, and a wide variety of international courts and countries across the globe. I instead evaluate the empirical plausibility of the theory and discuss research designs that may be used to examine individual observable implications more rigorously. First, I examine what proportion of backlashes are indeed initiated by leaders widely considered to be populist. I then offer narrative evidence that at least some of these backlashes follow the logic of the theory.

How Many Backlashes Are Initiated by Populist Leaders?

Table 2 lists the backlash episodes from table 1 by whether the leader relies heavily on populist mobilization. Despite an emerging consensus on a definition, there is no consensus on how to measure whether a leader is populist. There is, however, a literature on Latin America and Europe with a fair degree of consensus on whether leaders or the parties they represent are populist. The remaining leaders were evaluated based on the secondary literature. There are three leaders for whom the sources gave mixed assessments (indicated by a *): Kenyatta, Putin, and Cameron/May. To be conservative, I characterized all of them on the “not populist” side. Online appendix B offers more details on sources.

Table 2 Populism and backlashes against international courts

Eighteen of the twenty-eight backlash episodes originated from populist leaders. This is purely a descriptive statement rather than a causal or even a correlational statement. To start with the obvious, the table selects on the dependent variable. It only includes instances of backlash. Even if we had a dataset of all leaders that coded whether these could be considered populist (or not), then there would still be substantial inferential challenges. For example, the base propensity for engaging in backlash depends on exposure to international courts, which is difficult to establish given that the dependent variable consists of many courts. It would, for instance, be possible to examine whether populist leaders are more likely to renegotiate BITs or leave ICSID following unfavorable rulings.

That a leader is characterized as populist does not mean that the backlash fits the proposed theory. Moreover, there are some leaders that are not populist but have relied on populist mobilization strategies, such as the UK backlash against the ECtHR. The remainder of the article offers short narratives of individual backlash episodes to examine the plausibility of the theory.

Property Rights

Populists often mobilize around claims that those who control land, natural resources, or other property are morally undeserving of this ownership. They propose either redistribution to deserving others or nationalization such that the people rather than the corrupt elite benefit from natural resource wealth. International court judgments that constrain domestically popular redistribution initiatives have instigated several backlashes.

Land rights have been the most important engine for populist movements in Africa (Boone Reference Boone2009). The populist charge centers on inequitable and undeserving disproportionate landownership by ethnic or racial minorities, often dating back to colonial times. In most sub-Saharan countries property rights are poorly protected by domestic law. This creates incentives for majorities to expropriate minorities (Boone Reference Boone2009). International courts have not had much success in substituting for poor domestic property rights protections.

The most dramatic example is the SADC tribunal, which was eliminated altogether after ruling in favor of a white farmer, Mike Campbell, in a dispute over land seizures (Alter, Gathii, and Helfer 2016a). Mugabe described the 2008 ruling as “nonsense, absolute nonsense … . We have courts here in this country that can determine the rights of people.”Footnote 7 Zimbabwe’s domestic courts, including its supreme court, were initially receptive to legal complaints from farmers who had been expropriated without compensation (Thomas Reference Thomas2003). However, in the early 2000s Mugabe’s government replaced the (mostly white) judges that had frustrated land seizures with more sympathetic judges, partially in response to protests at courthouses and elsewhere (Meredith Reference Meredith2007). This was part of a campaign to decolonize the judiciary and return power to the people (Madinah Reference Madinah2001). The Zimbabwean government could have simply refused to implement the judgment given that domestic courts would surely not enforce it. Instead, Mugabe’s government immediately launched a campaign to delegitimize the tribunal, challenging its legal mandate and refusing to supply a Zimbabwean judge, ensuring that the tribunal did not have sufficient judges to hear new cases. Eventually, his tactics succeeded and the tribunal was abandoned altogether (Alter, Gathii, and Helfer Reference Alter, Gathii and Helfer2016b).

The theoretical expectation is not that all land rights rulings by international courts should trigger backlashes but only those that intersect with pre-existing domestic mobilization. Elites opposed IACtHR rulings in favor of indigenous land rights (Amiott Reference Amiott2002). But there was no pre-existing populist mobilization against indigenous peoples and no backlash against the IACtHR even if governments did not always comply in full and did not shy away from criticizing the court.

A second form of populist mobilization around property rights targets “neoliberalism” or at least the version of it pushed by foreign actors. The clearest examples are the left-wing populist movements in Latin America, which have mobilized around their opposition to neoliberalism and its advocates, especially the World Bank, the IMF, and the United States. Elite and foreign control of natural resources and domestic policies are at the center of the local populist mobilization (Castaneda Reference Castaneda2006).

The backlash against investment arbitration serves as the most straightforward illustration. It is no coincidence that Latin America’s left-wing populist governments, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, are the ones who have ended their commitments to ICSID (Waibel Reference Waibel, Kaushal, Chung and Balchin2010). Bolivia and Ecuador have even altered their constitutions to prohibit international investment arbitration. The opposition to ICSID was in part driven by costly adverse judgments (Haftel and Thompson 2017), but it was also ideological (Vincentelli Reference Vincentelli2010). In each country, there was pre-existing mobilization against neoliberalism and neoimperialism (Ellner Reference Ellner2012). These governments had been arguing for some time that foreign direct investment promotes imperialism and hinders the distribution of benefits from natural resources to the people. Venezuela left the Andean Community in 2006, objecting to bilateral free trade agreements that fellow member states Peru and Ecuador created with the United States.Footnote 8 Chavez claimed that “it makes no sense for Venezuela to remain in the CAN, a body which serves only the elites and transnational companies and not our people, the Indians and the poor” (cited in Malamud Reference Malamud2006, 3).

Each government preceded its attack against the international tribunals by curtailing domestic courts. A 2011 referendum gave Ecuador’s Correa the authority to reform the judicial system and pack the courts with his followers (Torre Reference Torre2013). Venezuela’s Chavez reduced the institutional requirements for appointing like-minded judges on courts (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009). In Bolivia, the Morales government introduced direct elections for national judges by the people, which increased confidence in the judiciary among government supporters but decreased overall confidence in the judiciary (Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2015).

Yet Latin-American left-wing populists are not the only ones who have lashed out at investment arbitration using populist rhetoric. The right-wing government in Poland announced its intention to get rid of BITs, also following (and during) domestic institutional reforms that were widely perceived to reduce judicial independence (Orecki Reference Orecki2017). India’s government led by prime minister Modi passed a constitutional amendment to alter the judicial appointment system but India’s Supreme Court struck it down citing it as a threat to judicial independence (Sen Reference Sen2017). Indonesia’s Widodo government is the outlier in that it has mobilized more strongly around sovereignty issues and foreign intervention with its domestic court system, especially over severe penalties for drug offenders.

That reductions in domestic judicial independence and commitment to international investment arbitration appear to coincide is puzzling given conventional theories, which see a commitment to international investment arbitration as a substitute for poor domestic property rights protections (e.g., Tobin and Rose-Ackerman Reference Tobin and Rose-Ackerman.2011). In this view, then, countries that limit judicial independence domestically should incur the highest cost in terms of reduced foreign investments if they also seek to exit the investment arbitration regime. Yet the examples presented here suggest that both left-wing and right-wing populist governments have nonetheless been willing to proceed on both tracks, even if exiting ICSID or canceling BITs do not automatically exempt a country from ISDS (Peinhardt and Wellhausen Reference Peinhardt and Wellhausen2016).

Minority Rights and Identity

A second liberal countermajoritarian task for international courts concerns the protection of unpopular minorities. I highlight four regularities. First, backlashes often occur over judgments that fit pre-existing populist mobilization around the identity of the polity. Second, backlashes often coincide with domestic court curbing. Third, populist leaders often believe that their instigation of a backlash increases their popularity. Fourth, populist efforts to reform international courts often fail to garner enough international support because local mobilization efforts are diverse.

Even though the Conservative governments in the UK are not populist per se, the British backlash against the ECtHR illustrates all four points and clearly relied on populist rhetoric. In 1998, the UK passed the Human Rights Act, which incorporated the ECHR into domestic law. This was a relatively uncontroversial act at the time (Ewing Reference Ewing1999). Its main effect was that British courts could now evaluate human rights claims by British citizens. Inevitably, most human rights cases were filed by prisoners, who sometimes won. These judgments became increasingly controversial. For example, in 2003 the Daily Mail ran a populist editorial saying that “Britain’s unaccountable and unelected judges are openly, and with increasing arrogance and perversity, usurping the role of Parliament, setting the wishes of the people at nought and pursuing a liberal, politically correct agenda of their own” (Greenhill Reference Greenhill2003).

Michael Howard, then the leader of the Conservative Party, tapped into this sentiment:

I believe that these are essentially matters for Parliament—for elected representatives, accountable directly to the people—to decide … . The Act has led to taxpayers’ money being used for a burglar to sue the man whose house he broke into and a convicted serial killer being given hard-core porn in prison because of his “right to information and freedom of expression.”Footnote 9

Until then, the ECtHR had barely emerged into these public debates. Yet, the ECtHR’s judgment in Hirst v. UK (2005) launched a perfect storm (Murray Reference Murray2013). The Court ruled that a British law that banned all prisoners from voting constituted a violation of the ECHR. The plaintiff had murdered his landlady with an axe and was photographed allegedly celebrating his court victory while smoking a joint and drinking champagne (McNulty, Watson, and Philo Reference McNulty, Watson and Philo2014).

The ECtHR judgment was not difficult to implement. The UK government needed to provide a rational basis for why some prisoners should not be able to vote, such as those who had committed a felony. But when the government proposed such a bill in 2011 it was defeated by an overwhelming majority (234 to 22) (McNulty, Watson, and Philo Reference McNulty, Watson and Philo2014). Few parliamentarians wanted to be on the record as supporting prisoner voting rights amidst growing populist sentiment. Prime Minister David Cameron, supposedly arguing for the cabinet’s proposal, stated during the debate that “it makes me physically ill to even contemplate having to give the vote to anyone in prison”(Hough Reference Hough2011).

The negative attention also affected public opinion: whereas 71% of the British public supported the ECtHR in 1996, in 2011 only 19% believed that the ECtHR had been a “good thing” and only 24 percent agreed that the UK should remain a member of the Court (Voeten Reference Voeten2013, 418). Some Tory MPs tried to capitalize on this by organizing a parliamentary vote to leave the ECtHR. Richard Bacon, the MP introducing the initiative, stated the populist rationale for stripping away the ECtHR’s authority rather than just fighting the judgment:

Although I do object to the idea of prisoner voting, my much more fundamental objection is to the idea that a court sitting overseas composed of judges from, among other countries, Latvia, Liechtenstein and Azerbaijan, however fine they may be as people, should have more say over what laws should apply in the UK than our constituents do through their elected representatives (Ross Reference Ross2012).

The motion received support from only 71 MPs and was not backed by the government. Negative sentiment against the ECtHR increased following its 2012 judgment that prohibited the UK from extraditing Islamic preacher and suspected terrorist Abu Qatada to Jordan for fears that he might be tortured there. The judgment upset then home secretary Theresa May so much that she argued that “it isn’t the EU we should leave but the ECHR and the jurisdiction of its court”(Asthana and Mason Reference Asthana and Mason2016). Prime Minister David Cameron responded that:

He has no right to be here, we believe he is a threat to our country. We have moved heaven and earth to try to comply with every single dot and comma of every single convention to get him out of our country. It is extremely frustrating and I share the British people’s frustration with the situation we find ourselves in.Footnote 10

As a Guardian editorial puts it, “this strategy allows the Conservative party to bang a populist drum on crime and immigration while blaming foreign European judges—all in one hit.”Footnote 11

Cameron used the UK’s chairmanship of the Council of Europe to propose reforms that were “a blueprint for clipping the Strasbourg Court’s wings and weakening supranational review of member states’ human rights practices” (Helfer Reference Helfer2012). Yet the UK was unable to create a coalition that would support the most far-reaching reforms. The final Brighton Declaration was much milder than the initial draft even if it sent a clear signal to the ECtHR that at least some member states wanted the court to be more restrained (Madsen Reference Madsen2016). Moreover, the May government has not (yet) followed through on its promise to exit the Court.

Another illustration is Ecuadorian President Correa’s attempt to curb the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) after the Commission interfered with domestic legal actions against journalists who wrote about the business dealings of one of Correa’s relatives and opened up other investigations into Ecuador’s treatment of journalists (Reuters News 2012). Correa framed his reform attempts as part of a struggle against the traditional families that controlled Ecuador’s media and the imperial influence of the United States. As Correa put it:

The thing is that the IACHR creates conflicts. Based in Washington, it thinks that it knows the reality of our peoples and on many occasions it has allied itself with the powers that be, which are part of the problem and not the solution, in the name of the sublime concept of freedom of expression. It is one thing for that to belong to businesses dedicated to the communications media and another for freedom of expression to be turned into a capacity for blackmail and manipulation. I believe that it is a bureaucracy that got used to acting at its own risk; it is heavily influenced by the vision of hegemonic countries who see freedom of expression as free enterprise (BBC Monitoring Americas 2012).

Correa did not want to get rid of the institution altogether but he wanted to eliminate “the last vestiges of neoliberalism and neocolonialism,” and “look for something that is new, better, and truly ours” (EFE News Service 2016). Yet the proposal to limit external funding for the Commission’s free speech investigations and move the Commission out of Washington, DC, failed to gather much support beyond the other three leftist populist leaders that were party to the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights (Venezuela, Bolivia, and Nicaragua).

Venezuela, under Hugo Chavez, exited the IACtHR in 2012 over a ruling that an anti-government terrorist, who had since moved to the United States, had been treated inhumanely in Venezuela. Non-compliance would have been a viable option. Chavez had stacked the domestic constitutional court with sympathetic judges. The domestic court concluded that the IACHR is not superior to the Venezuelan Constitution and that they could hold IACtHR judgments unenforceable (Huneeus Reference Huneeus2011a; Reference Huneeus2011b). Yet the Chavez government, who had long accused the court of being a mouthpiece of the United States, withdrew.

The case of the Dominican Republic follows a different logic. The Dominican Constitutional Tribunal in 2013 ordered the executive to review and retroactively rescind the citizenship of Dominicans of Haitian descent (Shelton and Huneeus Reference Shelton and Huneeus2015). This was a popular measure against a minority group that has long suffered discrimination. The IACtHR found that Dominican ruling breached Inter-American prohibitions on discrimination, forcible expulsions, and a duty to prevent statelessness. The Tribunal responded not just by criticizing or ignoring the IACtHR judgment but by ruling that the Dominican Republic’s acceptance of the IACtHR’s jurisdiction was unconstitutional (Shelton and Huneeus Reference Shelton and Huneeus2015). The Dominican government at the time and the court do not fit the populism label, even if the backlash originated in the kind of identity politics popular with populists.

African backlashes against the ICC have a diverse set of motivations. Especially in the cases of Burundi and Kenya, they were clearly motivated by (the threat of) actual prosecutions against government leaders. This fits traditional sovereignty arguments well. Yet there was also a broader mobilization against the presumed anti-African bias of the Court, which fits pre-existing populist mobilization on identity in some countries.

For example, in The Gambia Jammeh won the 1996 presidential election after having been one of the leaders of a 1994 coup that overthrew the previous government. Jammeh’s populist appeals centered on pan-Africanism (Ihonvbere and Mbaku Reference Ihonvbere and Mbaku2003). The new constitution vested the power in the president to appoint judges. Jammeh appointed a large number of foreign judges who had loyalty only towards him (Saine Reference Saine2008) and has otherwise curbed judicial independence (Perfect Reference Perfect2010). Jammeh launched a failed campaign against the ECOWAS Court, in which he was unable to garner support to restrict the Court’s jurisdiction on human rights issues (Alter, Gathii, and Helfer 2016b). In 2016, amidst a heated election, Jammeh labeled the ICC the ‘International Caucasian Court’ and initiated Gambian withdrawal from the court (Sandholtz, Bei, and Caldwell Reference Sandholtz, Bei and Caldwell2017). Jammeh believed that such a public campaign, highlighting the Court’s anti-African bias, would boost his support given his traditional mobilization strategies. Instead, Jammeh lost the election and, after an ECOWAS-authorized Senegalese intervention, handed over power to Barrow, who re-entered Gambia into the ICC.

Similarly, in South Africa President Jakob Zuma’s basis for domestic populist mobilization long relied on anti-Western and pan-African rhetoric (Guha Reference Guha2013). Zuma has also been embroiled in a series of struggles with a strong and independent Constitutional Court (Parpworth Reference Parpworth2017), including over the arrest of the indicted Sudanese President Omar Bashir during his visit to South Africa (Boehme Reference Boehme2017). As mentioned before, the Court declared the government’s declaration to leave the Rome Treaty a violation of the constitution.

This again illustrates that populist backlashes do not always succeed. Strong institutions can constrain populists. The efforts to form a multilateral coalition in the African Union to leave the ICC en masse failed. Populist leaders do consider the benefits that institutions bring and may not always follow up on threats that are sometimes offered for domestic political reasons.

Conclusions and Implications

The theory and evidence in this article suggest that at least some backlashes against international courts were initiated by governments based on pre-existing populist mobilization narratives that also played a role in curtailing domestic courts. But there are other reasons for backlashes, including the increase in binding and meaningful judgments and democratic reversals. Moreover, populist backlashes are not always successful. Populism as a thin ideology provides a thin basis for multilateral reform coalitions, making (partial) exit a more likely outcome than reform. Leaders who rely on populist mobilization may have incentives to reap short-term rewards from threatening to exit courts even if they do not immediately follow through. Moreover, some countries have returned to the jurisdiction of international courts after populists were defeated, as illustrated by the examples of Gambia after Jammeh and Peru after Fujimori. These considerations are important if we are to understand the potential impact of populism on international courts and international institutions more generally.

One theoretical implication is that domestic politics theories of international institutions ought to go beyond theorizing about variation in domestic institutions. Ideology is crucially important if we wish to understand why governments (threaten to) opt out of international institutions. I have focused on one type of opposition to liberal ideology—populism—and one kind of international institution—courts. But the argument may well apply more generally given that most international institutions are countermajoritarian from a domestic perspective.

The evidence offered here is at best a plausibility probe. More rigorous inquiries would require new data collection and research designs. They would also have to focus on narrower observable implications than the range discussed in this article. For example, it should be possible to examine whether reductions in domestic judicial independence indeed often precede withdrawals from the jurisdiction of international courts or whether populist leaders are more likely to exit BITs or ICSID following negative arbitration outcomes. Another potentially useful approach would be to examine whether judgments on land reform, prisoners, or immigrants indeed create more of an outcry where pre-existing populist mobilization on these issues exist. Moreover, the study of public opinion and international courts is in its infancy. We do not know whether voters for populist parties or individuals with populist attitudes are indeed more favorably disposed towards leaving the jurisdiction of international courts. Survey experiments might examine whether populist frames about international courts are indeed successful in persuading individuals. Finally, we do not know to what extent these backlashes are truly independent events or are linked in some way that may create tipping point effects.

Another important open question is what international courts can do about this challenge? Some suggest that courts could avoid backlash by not “overlegalizing” sensitive issues (Helfer Reference Helfer2002). Courts have developed strategies for this purpose. For example, the ECtHR’s margin of appreciation doctrine allows the court to grant governments some leeway in implementing the European Convention on Human Rights. For example, the 2009 Lautsi judgment reasoned that an Italian law that mandates a crucifix in each public school classroom violates freedom of religion. The decision caused immediate uproar. President Silvio Berlusconi, not known for his piousness, called it “one of those decisions that make us doubt Europe’s common sense.”Footnote 12 The populist right-wing Northern League, again not exactly a religious party, used local government control to distribute crucifixes in the main squares of villages and to enact bylaws that compel shopkeepers to display the crucifix (Mancini Reference Mancini2010). Italian populists argued that the crucifix had become a symbol of Italian identity (rather than religion) with an undertone of excluding Islam from that identity.Footnote 13 The ruling also faced the unprecedented opposition of thirteen state parties who joined in amicus briefs.

In 2011, the ECtHR’s Grand Chamber reversed the unanimous Chamber judgments 15–2, arguing that “the decision whether or not to perpetuate a tradition falls in principle within the margin of appreciation of the respondent State” (Lautsi and Others v. Italy, App no 30814/06, March 18, 2011 ). In other words, ECTHR wrote that it should grant a great deal of deference to states in deciding cases of identity. There is more general evidence that the ECtHR has become more restrained in response to criticisms (Stiansen and Voeten Reference Stiansen and Voeten2018). Moreover, investment tribunals have adopted the margin of appreciation doctrine and have become more predisposed towards states after withdrawals from ICSID or investment agreements (Langford and Behn Reference Langford and Behn2017). How judicial bodies respond to increased scrutiny is a promising area for future research.

International courts may not always have enough information to assess the political sensitivity of their judgments (Lupu Reference Lupu2013). The Lautsi case is an example. The initial Chamber judgment didn’t elaborate much on its societal implications and there was little attention and no third-party government submissions. That changed for the Grand Chamber judgment. The theory advanced here suggests that the Court may have to understand pre-existing domestic populist mobilization if it wants to assess whether a judgment may trigger a backlash. Yet judges may not always be in the best position to engage in these types of political judgments or to evaluate whether populist threats are credible. This could lead to backlashes that the judges had preferred to avoid or to overreactions where courts become more cautious across the board in an attempt to prevent backlashes. If this is so, then the implications of populist backlashes reach well beyond the immediate effects of the occasional withdrawals and institutional reforms.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A. Backlash Episodes

Appendix B. Is a Leader a Populist?

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719000975