Introduction

Scholars studying the evangelical vote in 2016 have asked which white evangelicals constituted the roughly 81% that voted for Donald Trump (Djupe and Claassen Reference Djupe and Claassen2018), looking at possible divides along the dimension of gender (Cassese Reference Cassese2020), religious practice (Layman Reference Layman2016), and religious beliefs (Margolis Reference Margolis2019).Footnote 1 One of the principal divides concerning the voting behavior of evangelicals is the difference between white and non-white evangelicals, which is well documented before and after the 2016 Presidential Election (McDaniel and Ellison Reference McDaniel and Ellison2008; McKenzie and Rouse Reference McKenzie and Rouse2013; Djupe and Claassen Reference Djupe and Claassen2018). As Wong (Reference Wong2015, 643) notes, “White and Black evangelicals share much in common as far as placing an emphasis on sharing one's faith, [and] belief that the Bible is the ultimate authority…at the same time, it has long been observed that in terms of their political orientations, the two groups could not be more different.” The effect of religion on political behavior cannot be clearly understood without accounting for the role that racial identity plays within a given religious context.

Explanations for the political divide between Black and white evangelicals focus on the historical and enduring separation between Black and white religious experiences, such as the exclusion of Black Christians from white religious spaces (Steensland et al. Reference Steensland, Robinson, Bradford Wilcox, Park, Regnerus and Woodberry2000; Bracey and Moore Reference Bracey and Moore2017; Margolis Reference Margolis2018; Tisby Reference Tisby2019; Yukich and Edgell Reference Yukich and Edgell2020). However, less attention has been paid to how the degree to which evangelicals feel attached to their racial identity—or conversely, white evangelicals' out-group resentment—may influence these differences. While we know little about the role of racial attitudes among evangelicals, the centrality of racial attitudes in modern American politics is firmly established (Cramer Reference Cramer2020). Additionally, scholars are exploring new ways of measuring in-group favorability and out-group animus. This includes work that revisits the conceptualization and measurement of racial resentment (Wilson and Davis Reference Wilson and Davis2011; DeSante and Smith Reference DeSante and Smith2020), that confronts the importance of capturing attitudes toward groups beyond the black–white binary (Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2020; Reny and Barreto Reference Reny and Barreto2022), and that further examines attachments to one's racial group (Gay et al. Reference Gay, Hochschild and White2016; Berry et al. Reference Berry, Ebner and Cornelius2021; Jardina Reference Jardina2019; Reference Jardina2020).

Because of the historical racial divide within American evangelicalism, and given that religious environments continue to be racially homogeneous (McKenzie and Rouse Reference McKenzie and Rouse2013), we might expect racial-group attachment among both Black and white evangelicals to be an especially powerful determinant of political preferences. Additionally, white evangelicals have higher levels of racial resentment than non-evangelical whites, which cannot simply be attributed to their evangelical identity (Calfano and Paolino Reference Calfano and Paolino2010). Instead, the relatively small and recent body of work in the area suggests white evangelicals are motivated by a heightened sense of perceived discrimination (Wong Reference Wong2018a) and that conservative racial attitudes may be as or more meaningful to evangelicals' politics as their issue attitudes toward traditional moral issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage (Claassen Reference Claassen, Djupe and Claassen2018). However, despite the prevalence and growth of literature on race and racial attitudes, and the demonstrated importance of examining religion through a racial lens, there remains a large body of racial attitudes research yet to be tested in the religious context.

Our research contributes to understanding the interaction of race and religion among evangelicals by evaluating how group attachment among Black and white evangelicals, and out-group resentment among white evangelicals, influences their political preferences. We assess the predictive power of Black identity, white identity, and racial resentment in determining attitudes toward traditional moral issues as well non-traditional issues, including racialized issues, among evangelicals. We then examine the association of these racial in-group and out-group attitudes with Black and white evangelicals' vote choice in 2012 and 2016. Our findings further our understanding of the differences in political behavior between Black and white evangelicals, who together comprise approximately one-third of the electorate.

First, we uncover limited effects of racial identity centrality in determining the political preferences of Black and white evangelicals. Black identity, although highly salient among Black evangelicals, does not explain their varying attitudes regarding traditional issues, non-traditional and racialized issues, or vote choice. Our findings stand in contrast to the implicit assumption that the political divide between Black and white evangelicals is driven by racial in-group attachments. Second, our findings point to a deep divide among white evangelicals along the dimension of racial resentment. This division is consistent across a multitude of political issues, and while the majority of white evangelicals hold high levels of racial resentment, our model predictions for white evangelicals with lower levels of racial resentment are quite similar to the average predicted political attitudes of Black evangelicals. Thus, the division between Black and white evangelicals' political preferences could be primarily driven by white evangelicals' racial animus.

Following our results, we discuss possible mechanisms that might facilitate these differences, such as church attendance, which may provide a conduit through which racial in-group favoritism may be operating in religious spaces. We conclude by discussing the limitations of our data and further outlining our contributions as well as future routes for related research.

The Political Divide between Black and White Evangelicals

The divide between Black and white evangelicals is prevalent throughout history. Due to white Christians' exclusion of Black slaves and free Black Americans in their religious services, Black Christians formed separate spaces to worship (Tisby Reference Tisby2019). Black churches serve as social and political hubs in many communities, fulfilling vital civic functions like registering parishioners to vote, aiding them in navigating the bureaucratic system (Brown and Brown Reference Brown and Brown2003; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2008; Brown Reference Brown2009), and hosting events for candidates in their churches (Fausset and Robertson Reference Fausset and Robertson2017). The uniqueness of the Black church is even reflected in the measurement of American religion, with Black Protestants often being separated into a category of their own (Steensland et al. Reference Steensland, Robinson, Bradford Wilcox, Park, Regnerus and Woodberry2000).

Importantly, this partition is not explicitly due to theological differences, but is due to a history of racism and discrimination from white Christians (Wald and Calhoun-Brown Reference Wald and Calhoun-Brown2014). As Margolis (Reference Margolis2018, 150) writes, “In contrast to white conservative Protestants, African Americans’ history of social, legal, and religious segregation has allowed for a theological perspective that focuses on predominately liberal ideas of equality and justice to flourish.” Because common measurement of religion is in practice a measurement of racial-religious categorization, often only in the case of Black Americans, it is difficult to estimate how many Black Americans can be classified as evangelicals based on their theological beliefs or religious identity (Shelton and Cobb Reference Shelton and Cobb2017). According to the Pew Research Center, a remarkable majority (67%) of Black Americans identify as either evangelical or as Black Protestants.Footnote 2

While Black Christians share a common history of forced segregation from white churches, less attention is paid in considering how white evangelicals shared history of dominating the social order may influence both their politics and religion. White evangelicals represent a sizeable portion of whites (29%) and a solid voting bloc within the American electorate, comprising roughly one-quarter (23%) of voters, the largest racial-religious bloc of voters in the United States (Wong Reference Wong2018a). White evangelicals firmly consolidated behind the Republican Party by the year 2000, and they now make up the backbone of the party (Layman Reference Layman2001; Margolis Reference Margolis2018). In fact, the white evangelical coalition is so strong that a candidate taking on an evangelical identity can expect to see increased Republican support (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Green and Layman2011). The candidacy and election of Donald Trump did not change the strength of this coalition (Djupe and Claassen Reference Djupe and Claassen2018; Cassese Reference Cassese2020); conversely, his election arguably reflected the profound strength and endurance of it.

While having an evangelical identity does have a consistently conservatizing effect on political attitudes across racial groups, this effect is uniquely strong among white evangelicals (Wong Reference Wong2018a). These differences are apparent when evaluating Black and white evangelicals' differences in partisanship (Calhoun-Brown Reference Calhoun-Brown1998; McDaniel and Ellison Reference McDaniel and Ellison2008), congregational civic engagement (Brown Reference Brown2009), and church political context (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Khari Brown, Phoenix and Jackson2016). Many of the racial divides prevalent in the country as a whole also exist within churches, and in some cases these differences are even more noticeable. While recent scholarship has increasingly parsed out these important differences, the discipline needs further clarification as to why these divisions continue.

Racial Attitudes as An Explanation for the Divide

The dominant paradigm in the literature suggests white evangelicals are drawn toward conservatism and the Republican Party for their stances on traditional moral issues such as abortion and legal recognition of marriage equality (Olson et al. Reference Olson, Cadge and Harrison2006; Lewis Reference Lewis2018; Swank Reference Swank2020). The Republican Party was able to mobilize evangelical Christians by bringing traditional moral issues to the forefront of the political arena (Wilcox Reference Wilcox1992). This mobilization permeated into the elite realm as the Republican Party built networks and special interest groups centered around marshalling evangelicals to the polls around these issues, which has led to landslide majorities for the GOP among white evangelicals in every presidential election since 1980.

However, a growing body of scholarship suggests that these moral issues might not be the source of evangelical support for the Republican Party, with some positing they might be a guise (Marsh Reference Marsh2021). Scholars have explored race and racial attitudes as an explanation for evangelical political divisions, as there tends to be similar agreement among both Black and white evangelicals on traditional moral issues (Wong Reference Wong2015; Philpot Reference Philpot2017). Wong (Reference Wong2018a, 81) finds that white evangelicals' conservatism is “driven by a sense of in-group embattlement,” in which white evangelicals feel their racial group is discriminated against more than others and that their Christian values are under attack. While whites in general have increasingly reported feeling discriminated against (Marsh and Ramírez Reference Marsh and Ramírez2019), evangelical Protestants in the South are even more likely to report racial discrimination (Mayrl and Saperstein Reference Mayrl and Saperstein2013). Furthermore, Emerson and Smith (Reference Emerson and Smith2001) argue that white evangelicals are particularly ill-equipped to comprehend and recognize structural racial inequality because of their cultural disposition that emphasizes individualism, personal relationships, and anti-structuralism. This orientation may help explain previous research that posits white evangelicals' high levels of racial resentment come from ideological disagreements rather than evangelicalism alone or anti-black affect (Calfano and Paolino Reference Calfano and Paolino2010). However, some scholars do conclude that racial attitudes motivate white evangelicals' political attitudes (Claassen Reference Claassen, Djupe and Claassen2018). Thus, racial attitudes are relevant in the evangelical context.

While a large portion of the racial attitudes literature has focused on out-group attitudes among whites and in-group attitudes among Blacks (Hutchings and Valentino Reference Hutchings and Valentino2004), much of the work on racial attitudes has not yet been taken into account when examining evangelicals. Black Americans' in-group identity has become a central factor in their political organization (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020), but the impact of racial identity is still dependent on the context in which it is activated (White Reference White2007). Black identity is associated with more liberal policy preferences when the policies are seen as more helpful to the group (Craemer et al. Reference Craemer, Shaw, Edwards and Jefferson2013). These forces replicate among the religious, and religious identity and practice can even amplify racial group attachment. As Wilcox and Gomez (Reference Wilcox and Gomez1990, 271) notes, “Black religion is an important source of Black identity and a stimulus to a political involvement.” However, Black evangelicals still hold conservative positions on what are viewed as the traditional moral issues among evangelicals (Calhoun-Brown Reference Calhoun-Brown1998; Wong Reference Wong2018a).

Consequently, we expect that the higher levels of Black identity found among Black religious populations will lead to more conservative positions on traditional issues, given that, as Philpot (Reference Philpot2017) notes, African-Americans have historically been conservative on salient moral issues like same-sex marriage. However, we hypothesize that Black identity will be associated with liberal positions on non-traditional and more racialized issues. Finally, previous scholarship has highlighted group consciousness as a driver of Democratic vote choice among Black Americans (Philpot Reference Philpot2017; White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020). Thus, we hypothesize that an increase in Black identity will be negatively associated with voting for a Republican presidential candidate.

A newer development within the literature on racial in-group favoritism is a growing focus on white identity (Berry et al. Reference Berry, Ebner and Cornelius2021; Jardina Reference Jardina2019; Reference Jardina2020). Theories of white identity rest on the assertion that whites may possess in-group favorability and seek policies that specifically benefit them as whites. White identity is characterized by how important one feels being white is to their identity, as well as their sense of commonality among whites, and has been triggered by a demographically and culturally changing America. Jardina (Reference Jardina2019, 106) finds that 19% of whites high in white identity identify as Evangelical Protestants. Overall, the religious breakdown of whites with high white identity matches closely to the distribution of religion across the broader white population; the exception to this is among white non-religious respondents who tend to fall lower on the white identity measure.

Previous scholarship has found that white identity is associated with more conservative views on immigration and voting for the Republican Party; however, it is not associated with racialized policies that are not viewed as having a negative effect on whites (Jardina Reference Jardina2019). Moreover, although the Black church has been a source of increased racial identity among Black Christians, this link has not yet been made among white Christians. Thus, there is no theoretical reason for us to believe that white identity will significantly move the needle among white evangelicals on the traditional moral issues of same-sex marriage and abortion. Furthermore, we do not expect white identity to be associated with non-traditional issues that are not directly related to the in-group, such as gun control, affirmative action, and the death penalty. However, we do expect white identity will be linked with conservative attitudes on immigration because of the perception that restricting immigration will benefit white Americans. Finally, we expect that an increase in white identity will lead to a positive association in voting for the Republican presidential candidate (Jardina Reference Jardina2020).

While white identity is meaningful in certain contexts, even when modeled together, whites' racial resentment is still a consistently strong predictor of political behavior (Jardina Reference Jardina2020). We continue this line of research by comparing racial resentment and white identity within the evangelical context. Scholars have previously shown that the American political context is becoming increasingly racialized, and whites' out-group animus is now associated with issues that were previously not considered racially salient (Tesler Reference Tesler2012; Enders and Scott Reference Enders and Scott2019). In light of these findings, we hypothesize that the pervasiveness of racial resentment will be profound among white evangelicals as we speculate that the religious context found in many predominately white, evangelical churches serves as a harbor for these attitudes. In the sections that follow, we outline our measurement strategies and consider the role of in-group and out-group racial attitudes in three different contexts. First, we present our results for traditional evangelical issues, such as abortion and gay marriage. Second, we examine non-traditional evangelical issues, such as gun control, affirmative action, the death penalty, and immigration. Third, we analyze the influence of racial identity centrality and racial resentment on electoral outcomes, namely the likelihood of supporting Mitt Romney in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016. We follow the presentation of our results with a discussion of other key findings that differentiate Black and white evangelicals.

Data and Methods

How do racial group attitudes shape the political preferences of Black and white evangelicals? To analyze this question, we rely on the 2012 and 2016 ANES Time Series Studies.Footnote 3 Our sample is Black (n = 635) and white (n = 1145) respondents who are identified as Evangelical Protestants according to their denominational affiliation (Steensland et al. Reference Steensland, Robinson, Bradford Wilcox, Park, Regnerus and Woodberry2000).Footnote 4

Scholars take varied approaches to measuring who is and is not an evangelical (Hackett and Lindsay Reference Hackett and Lindsay2008). As Margolis (Reference Margolis2018, Reference Margolis2019) notes, religion, and specifically the evangelical identity itself, is politicized, which influences who chooses to identify or de-identify with a particular religious group (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Layman, Green and Sumaktoyo2018; Djupe et al. Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Sokhey2018; Egan Reference Egan2020). This results in religious identity being a complex concept to measure.

The most widely used measure of religious tradition, RELTRAD, is derived from Steensland et al. (Reference Steensland, Robinson, Bradford Wilcox, Park, Regnerus and Woodberry2000). RELTRAD consists of seven possible categories: Mainline Protestant, Evangelical Protestant, Black Protestant, Roman Catholic, Undifferentiated Christian, Jewish, other religion, and not religious. Others utilize the binary born-again question, which asks respondents “Would you call yourself a born-again Christian, that is, have you personally had a conversion experience related to Jesus Christ?”

While Steensland and colleagues argue that a Black Protestant category is necessary due to the historical exclusion of Black Christians from white churches, Wong (Reference Wong2015; Reference Wong2018a; Reference Wong2018b) finds that white evangelicals (as measured by the born-again question) are uniquely conservative when compared to Asian American, Black, and Latino evangelicals. Additionally, coding schemes for implementing RELTRAD vary. Burge and Lewis (Reference Burge and Lewis2018) use a combination of RELTRAD coding and the born-again question, but exclude Black respondents from answering the born-again question. As Shelton and Cobb (Reference Shelton and Cobb2017) note, the Black Protestant category often conflates a common racial identity with a common religious experience in the historically Black Church. The born-again question in the ANES is asked of Christians affiliated with non-evangelical denominations, such as Catholic respondents, and these respondents may (and sometimes do) respond affirmatively (Welch and Leege Reference Welch and Leege1991). While each of these approaches to measuring evangelicals has various strengths and shortcomings, we utilize a denominational approach.Footnote 5

Our key independent variables are racial identity and racial resentment. We measure Black identity and white identity through identity centrality, which is measured through an individual's response to the question, “How important is being Black/white to your identity?”(Hooper Reference Hooper1976; Jardina Reference Jardina2020). Responses vary from “Not at all important” (0) to “Extremely Important” (4). While this question has been asked to Black and other non-white respondents for many years, white respondents have only been asked since the 2012 ANES (Jardina Reference Jardina2019). To strike a balance between the need for increased observations of Black evangelicals in our analyses and question availability for whites, we use a pooled sample of the 2012 and 2016 ANES in all of our issue attitude analyses.

We also test our hypotheses by examining how whites' racial attitudes affect their policy attitudes. We investigate racial resentment among the sample of white evangelicals in which we take an individual's average response—ranging from “Disagree Strongly” (0) to “Agree Strongly” (4)—to the standard four-item index (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996).Footnote 6

There exists a rich scholarly discussion on measuring racial attitudes, and particularly about whether the racial resentment measure accurately captures them (Kinder and Mendelberg Reference Kinder, Mendelberg, Sears, Sidanius and Bobo2000; Sears and Henry Reference Sears and Henry2003; Huddy and Feldman Reference Huddy and Feldman2009; Wilson and Davis Reference Wilson and Davis2011; Cramer Reference Cramer2020; DeSante and Smith Reference DeSante and Smith2020). Additionally, while limited work exists evaluating the racial resentment measure among Black Americans (but see Orey et al. Reference Orey, King, Titani-Smith and Ricks2012; Frasure-Yokley Reference Frasure-Yokley2018; Kam and Burge Reference Kam and Burge2018), we refrain from incorporating racial resentment in our Black evangelical models. Measuring racial resentment in the context of Black respondents is theoretically unclear, but could be viewed as one of negative in-group attitudes, contrary to a measure of negative out-group bias when applied to whites (Orey et al. Reference Orey, King, Titani-Smith and Ricks2012; Kam and Burge Reference Kam and Burge2018). At a minimum, it is clear racial resentment does not work for Black respondents in the same way it does for white respondents.

Jardina (Reference Jardina2020) finds whites' racial resentment to be concentrated toward the higher end of the scale and white identity to be concentrated toward the lower end of the scale. Additionally, Black respondents report higher levels of racial identity centrality than do whites. While the mean for Black identity is higher than that of white identity, we find higher average racial identity among both groups of evangelicals compared to their non-evangelical counterparts (Black evangelicals:+0.24, p < 0.05; white evangelicals:+0.20, p < 0.01). White evangelicals also harbor higher levels of racial resentment than white non-evangelicals (+0.39, p < 0.01). We find little difference when we examine 2012 and 2016 separately; Black and white identity among evangelicals does not significantly change, however white evangelicals' racial resentment decreases slightly in 2016 (−0.11, p < 0.1).Footnote 7

Our outcome variables include a variety of issue attitudes and presidential vote choice in 2012 and 2016. Table 1 displays the dependent variables, their possible values, and the values for which we present predicted probabilities. We model attitudes toward two traditional evangelical issues—abortion and marriage equality—and four non-traditional issues: gun control, affirmative action, the death penalty, and immigration. Finally, we present predictions for voting for the Republican presidential candidate in 2012 (Romney) and 2016 (Trump). While the voting models are separated by year, the attitudinal models feature the pooled sample.

Table 1. Dependent variables

We control for a host of other variables in our models such as the respondent's age, education, income, sex (1 = female, 0 = otherwise), and the year (1 = 2016, 0 = 2012). Additionally, we account for church attendance, which ranges from Never (0) to Every Week (4), Biblical Literalism, which ranges from whether the Bible is written literally and by God (2) or is a creation of humanity (0), and religious guidance, which ranges from religion is not important (0) to religion providing a great deal of guidance (4).

In models predicting church attendance and Biblical Literalism, among the combined sample of Black and white evangelicals, we find no statistical association between race nor racial identity.Footnote 8 We do find racial resentment to be positively associated with Biblical Literalism, or an increased likelihood to take the Bible as the literal word of God. We find a negative association between racial resentment and frequency of church attendance.

Results

We present our results as follows: first, we introduce our models predicting political attitudes among Black and white evangelicals toward traditional and non-traditional issues. We present results from models using the combined sample of Black and white evangelicals with an interaction between race and racial identity, and we specify separate models for Black and white evangelicals in which we test racial identity for both groups and racial resentment for white evangelicals. After this, we examine vote choice among the two groups. In all presentations, we focus on the predictive power of our key independent variables, racial identity, and racial resentment.Footnote 9 Each plot displays the predicted probability where each color represents Black evangelicals' racial identity, white evangelicals' racial resentment, and white evangelicals' racial identity, respectively.

We examine Black and white evangelicals' attitudes toward six issues: abortion, gay marriage, gun control, affirmative action, the death penalty, and immigration. While this list is by no means comprehensive, we select a variety of topics that tap into both traditional evangelical issues and non-traditional issues, including issues where we would expect to see racial attitudes to be especially relevant. All models in this section represent the pooled 2012 and 2016 ANES sample. First we present our results on traditional issues, abortion, and marriage equality, in Figure 1. Our models utilize the full scale, but we present the results for the predicted probability of choosing the most liberal option for both of these issues.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities toward traditional issues

Note: Graphs display predicted probabilities from ordered logistic regressions. Predictions for Black Identity and White Identity from an interaction between Racial Identity Centrality and Race (Black or white). Predictions for Racial Resentment among white evangelicals only. Models include controls for demographics and political covariates, church attendance, and Biblical Literalism

Among both Black and white evangelicals, racial identity has a positive effect on taking a more liberal position on abortion, but this effect is only statistically significant among white evangelicals. White evangelicals are overall less likely to hold liberal positions on abortion than Black evangelicals. Turning to attitudes toward same-sex marriage, there are neither significant differences between Black and white evangelicals' nor within either group based on racial identity.

However, here we find the role of racial identity centrality is conditional on race—whereas Black identity is associated with a higher probability of believing gay and lesbian couples should be allowed to legally marry, white identity is negatively associated with this belief. The coefficient for racial resentment is not significant in our model on abortion opinions, but racial resentment is significant and negatively associated with liberal attitudes toward same-sex marriage. The average predicted probability for taking the most liberal position on marriage equality is lowest among the most racially resentful white evangelicals. This finding is consistent with previous work showing that prejudice can span over multiple issue dimensions (Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Lavine and Federico2017), that racial resentment is associated with political attitudes beyond racialized issues (Enders and Scott Reference Enders and Scott2019), and even that the number of political issues that are racialized is increasing (Tesler Reference Tesler2016; McCabe Reference McCabe2019). As Kinder and Kalmoe (Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017, 105) note, public opinion on moral issues, such as same-sex marriage, are “determined to a large extent by the sentiments citizens feel toward the social groups implicated in the policy.” Consequently, white evangelicals' negative attitudes toward same-sex marriage may be correlated with negative attitudes toward racial outgroups, namely African Americans (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities toward non-traditional issues

Note: Graphs display predicted probabilities from ordered logistic regressions. Predictions for Black Identity and White Identity from an interaction between Racial Identity Centrality and Race (Black or white). Predictions for Racial Resentment among white evangelicals only. Models include controls for demographics and political covariates, church attendance, and Biblical Literalism

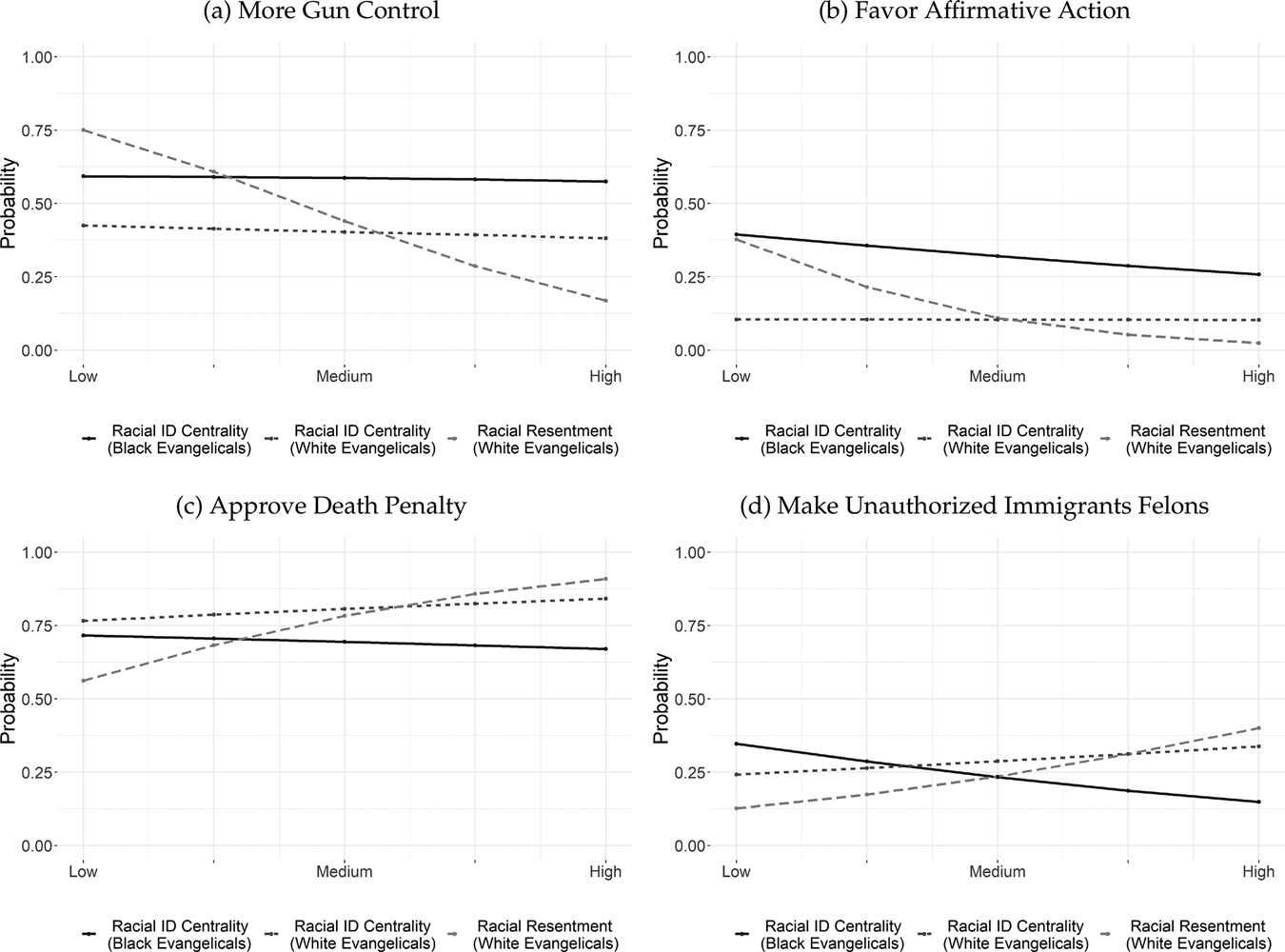

Next we turn to issues that are less associated with moral positions held by evangelicals, many of which are more racialized. Gun control is measured as a binary variable, grouping the two more conservative responses (“Make it easier” to buy a gun or “keep rules about the same”) and separating the only option that would “make it more difficult” to buy a gun (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Andrews, Goodwin and Krupnikov2020). Affirmative action refers to a seven-point scale measuring how much a respondent favors allowing universities to consider race when choosing students, in order to increase the number of Black students. We present the most liberal responses for these two questions in Figures 3a and 3b. We display the predicted probabilities of approving (strongly or not strongly on a four-point scale) of the death penalty in Figure 3c and holding the most conservative view toward immigration, which is to “make all unauthorized immigrants felons and send them back to their home country” in Figure 3d.

Figure 3. Voting behavior of Black and white evangelicals

Note: Graphs display predicted probabilities from binary logistic regressions. Predictions for Black Identity and White Identity from an interaction between Racial Identity Centrality and Race (Black or white). Predictions for Racial Resentment among white evangelicals only. Models include controls for demographics and political covariates, church attendance, and Biblical Literalism

For all of the four non-traditional issues, white evangelicals hold more conservative attitudes than Black evangelicals. Among Black evangelicals, we see few significant effects of racial identity on political attitudes. Regardless of the strength of one's Black identity, Black evangelicals hold relatively homogeneous political opinions toward gun control and the death penalty, and while there is a negative relationship between Black identity and favoring affirmative action, this effect is not statistically significant. However, there is a positive and significant association between Black identity and liberal positions on immigration. As displayed in Figure 3d, Black evangelicals with high levels of Black identity are the least likely to take the position of “Make all unauthorized immigrants felons and send them back to their home country.” Further, the immigration model is the only non-traditional issue in which the interaction between race and racial identity centrality is statistically significant; Black identity is associated with liberal preferences, whereas white identity is associated with more conservative attitudes. Among white evangelicals, we do not find white identity to significantly predict attitudes toward any of these four issues.

Our most consistent finding is that racial resentment significantly influences white evangelicals' political preferences, and in all cases has a conservative effect. In each case, predictions for white evangelicals low on racial resentment are very similar to the predicted attitudes of Black evangelicals. While in-group affection measured as Black and white identity is not significantly associated with most of these issues (with the exception of abortion among white evangelicals and immigration among Black evangelicals), racial resentment has a negative (conservative) effect in each model and is statistically significant in all cases except abortion attitudes.

Finally, we turn to an examination of electoral outcomes in presidential vote choice for both the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections on our primary independent variables: Black identity, white identity, and racial resentment. We present the predictions for Mitt Romney in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016 here. Because we cannot use the pooled 2012 and 2016 sample for these models, we are limited in our ability to model Black evangelicals separately from white evangelicals. We continue to rely on our full sample of Black and white evangelicals and include an interaction between race and racial identity in the model. We also separately specify a model among white evangelicals that includes covariates for white identity and racial resentment.

Figure 3 displays our results for vote choice. Our findings for voting behavior follow similar trends to those presented for issue attitudes. First, we note the strong divide between Black and white evangelicals in 2012 and 2016. White evangelicals were significantly more likely to vote for both Romney and Trump. However, we find no evidence that Black identity nor white identity among evangelicals is a strong predictor of voting behavior. Alternatively, we continue to find racial resentment to be significantly associated with voting for both Romney and Trump.

Discussion

Our results provide mixed support for our expectations. While Black identity and white identity is higher among evangelicals than the general population, these group attachments are not particularly powerful predictors of political preferences. Our results suggest that racial in-group favoritism operates similarly among Black and white evangelicals in many cases, though there are some issues for which it operates differently. We present two of these cases—marriage equality and immigration—in which Black identity is associated with more liberal positions and white identity is associated with more conservative positions. The interaction term in these two models is statistically significant, but we also find Black identity and white identity moves evangelicals in opposing directions when it comes to attitudes toward the death penalty. Black evangelicals are more likely to disapprove of the death penalty as Black identity increases, but white evangelicals are more likely to approve of the death penalty as white identity increases. Consistently, we find that racial resentment among white evangelicals is strongly associated with conservative positions on all issues.

We recognize some limitations to our data and design in answering these questions. Our main restriction comes from the small sample of Black evangelicals in our analysis and the limited variation of our key variables among both Black and white evangelicals. Nearly 83% of Black evangelicals reported that being Black is either “Very” or “Extremely Important” to their identity, and very few (approximately 7%) Black evangelicals reported being Black to be “A little” or “Not at all important.” While there is more variation in white evangelicals' reports of racial identity, almost 80% of white evangelicals fall above the midpoint on the racial resentment index. With a larger sample of Black evangelicals and more variation on our key variables, we would likely be able to make more precise estimates.

Beyond our key independent variables, racial identity centrality and racial resentment, there are other relationships found in our analysis that are worth considering. Notably, the relationship between church attendance and our dependent variables provides some insight to the mechanisms behind our expectations. Our theoretical framework for why Black identity and white identity may be associated with political preferences was derived from historical schisms within evangelicalism and American Christianity broadly. Because white Christians have created exclusionary religious spaces (Bracey and Moore Reference Bracey and Moore2017; Tisby Reference Tisby2019), Black religious experiences can amplify racial identity (Wilcox and Gomez Reference Wilcox and Gomez1990). While we do not know of any studies linking white identity with religious experiences, we could theorize similarly for white evangelicals, that their religious experiences and spaces can amplify and intensify their racial identity. Following these expectations, Black and white evangelicals who attend church more frequently should hold more conservative opinions toward traditional issues. Further, Black evangelicals should hold more liberal positions toward non-traditional issues, but white evangelicals attending church more frequently will hold more conservative opinions toward all issues.

We find Black identity is strongly associated with increased church attendance among evangelicals but white identity is weakly associated with decreased church attendance. Our results for traditional issues do show church attendance among both Black and white evangelicals to be significantly associated with more conservative attitudes toward abortion and marriage equality. While the relationship between church attendance and non-traditional issues is not as clear, the coefficient for church attendance among Black evangelicals is positive in our models predicting liberal attitudes on gun control, affirmative action, and immigration, but not the death penalty. Our results lead us to believe church attendance is not only an important environment for political socialization (Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe and Gilbert2009), but that this socialization is raced (Yukich and Edgell Reference Yukich and Edgell2020), is consequential for racial attitudes, and may even be capturing the expected effects of racial identity.

Conclusion

These findings make multiple contributions to the existing scholarship on evangelicals and the racial divisions within this group. Our results lend credence to the scholarship showing that American politics has become racialized in multiple contexts (Tesler Reference Tesler2012). Specifically, we look at a portion of the population that holds higher than average racial identity (both Black and white evangelicals) and higher racial resentment (white evangelicals) than their non-evangelical counterparts. While we find limited cases where in-group racial attitudes are driving political attitudes, we find that racial resentment consistently drives white evangelicals to more conservative positions. These results hold even while accounting for political and demographic variables and three measures of religiosity or religious salience: views toward the Bible, frequency of church attendance, and degree to which religion provides guidance in daily life. White evangelicals hold significantly more conservative political preferences than Black evangelicals, and while there are few white evangelicals with low levels of racial resentment, our predictions for those few are quite similar to attitudes held by Black evangelicals.

Our results suggest racial in-group affection—conceptualized here as the strength of one's Black and white identity—has a limited role in determining the issue attitudes and vote choice among a sample that reports higher than average on these measures. While we find increased levels of Black and white identity among evangelicals compared to their non-evangelical counterparts, the effects of this more salient racial identity vary in their explanatory power regarding evangelicals' politics. We find heightened levels of racial identity centrality among both Black and white evangelicals, and we theoretically expected this could be due to the religious social context that evangelicals inhabit. Previous scholarship has documented how attendance at a political church can be the catalyst for political participation among Black evangelicals (Calhoun-Brown Reference Calhoun-Brown1998; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2008). The relationship in our models between church attendance and political attitudes suggests this could be the case. Considering these results, however, future work in the area should continue to contemplate the elevated presence of racial identity centrality among evangelicals.

We utilize a denominational approach to measuring evangelicalism, and we do hope future work will consider how various religion measurement strategies are particularly consequential for understanding the racial context of religion. Related to this point, we ponder how racial attitudes and religious identity influence one another and how individuals weight these identities when considering political preferences. While it is plausible that whites' religious identity is heavily tied to their own racialized conception of religion, that lack of variation on many existing measures of religious salience do not result in the variation that may be necessary to test this proposition. Additionally, we utilize just one measure of racial in-group favoritism here, but there is a burgeoning collection of literature on racial in-group and out-group attitudes (e.g., Wilson and Davis Reference Wilson and Davis2018; Chudy et al. Reference Chudy, Piston and Shipper2019; Jardina Reference Jardina2019; Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2020; Chudy Reference Chudy2021) that could provide a more complete understanding of evangelicals' racial divisions.

There remains a vast opening for research on the racial attitudes of evangelicals and other religious populations. We demonstrate that the divide between Black and white evangelicals cannot necessarily be attributed to Black evangelicals' attachment to their racial group. Instead, we do find that white evangelicals' out-group resentment is strongly associated with their political preferences. Our results show that the enduring racial divides among evangelicals are more complex than a binary measure of race can capture, and racial group attachments and animus among evangelicals remain pervasive and consequential for American politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048322000074.

Levi Allen is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame. His research focuses on religion and politics, the political parties, and determinants of vote choice.

Shayla Olson is a Ph.D. student in Political Science and Scientific Computing and an MA student in Statistics at the University of Michigan. She researches in the areas of racial and ethnic politics and political communication within U.S. religious contexts.