Concepts of depression have changed markedly over the past century. In the early part of the 20th century, Kraepelin described depression as a long-term affliction, characterised by recurrences and chronicity. In the 1960s and 1970s came the psychopharmacological revolution. Newly developed medications for depression — monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) — caused dramatic improvement within weeks. These developments led to a reformulation of depression as an illness that could be ‘cured’ quickly, like a bacterial infection. The development of short-term, focused psychotherapies such as cognitive—behavioural and interpersonal therapy paralleled the psychopharmacological advances, and also fostered this view of depression as a short-term illness.

Research findings emerging in the 1980s challenged this view. For example, the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Program of the Psychobiology of Depression involved a multi-year follow-up of over 400 patients. After 15 years, only one in eight of these patients had recovered from their original episode and stayed well (Reference Keller, Lavori and MuellerKeller et al, 1992). Over 80% had suffered at least one recurrence, and 6% had remained chronically depressed throughout the entire 15-year period.

These and other findings, as well as experience with antidepressant pharmacotherapy, have led physicians to return to the Kraepelinean notion of depression as a long-term, recurrent and often chronic illness. Treatment for the disorder has both short-term and long-term aspects: short-term treatment includes acute and continuation phases, while long-term treatment consists of the maintenance phase (Reference KupferKupfer, 1991).

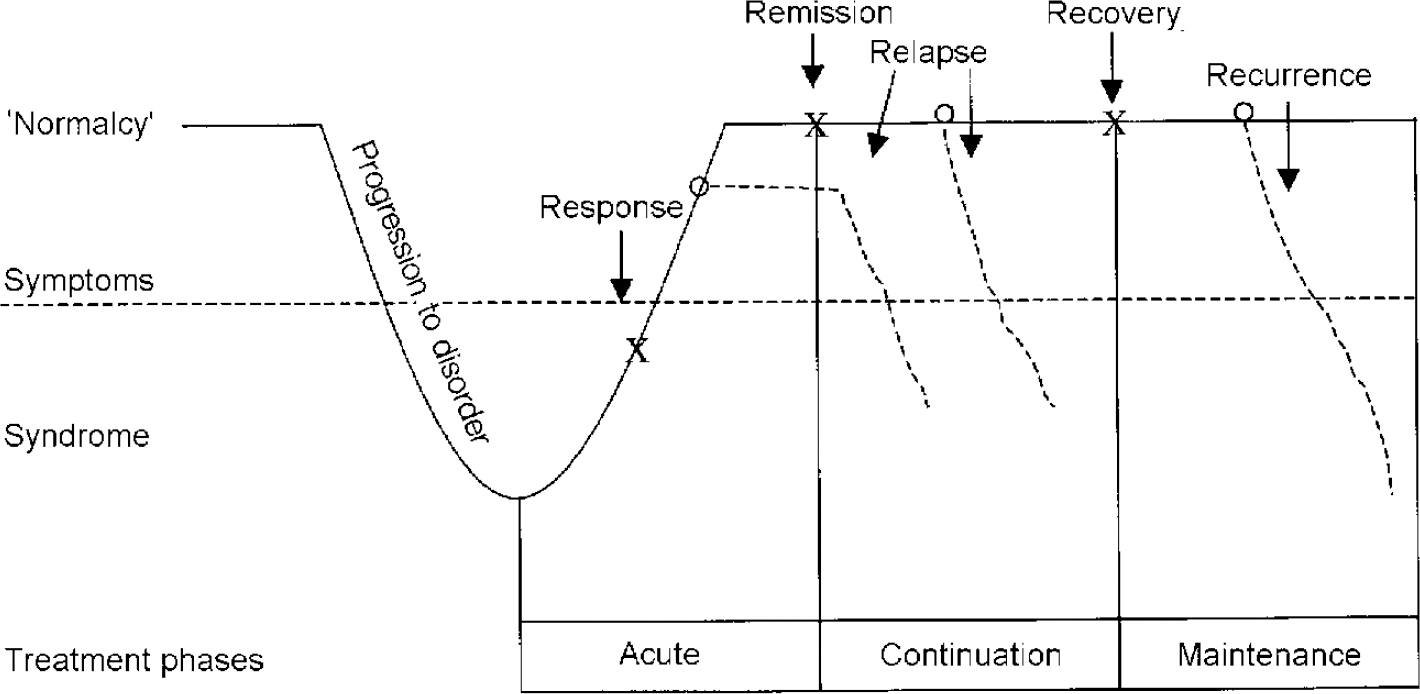

The acute phase involves stabilisation of the acute symptoms and generally lasts up to 3 months (Fig. 1). However, in complicated cases, acute treatment may take considerably longer. The continuation phase begins with stabilisation and ends at the point at which the depression would have ended had there been no successful treatment (often thought to be an additional 6-12 months beyond acute symptom resolution). If depressive symptoms return during the continuation period, it is considered to be a relapse into the original episode of illness. Thus, treatment for a single episode can take over a year, but in most cases will last 6-12 months. The maintenance phase involves prevention of new episodes (recurrences) and can extend for years.

Fig. 1 Response, remission, recovery, relapse and recurrence of depression. From Kupfer (Reference Kupfer1991).

ACUTE TREATMENT

The efficacy of pharmacotherapy for the acute phase of the treatment of depression is well established. Janicak et al (Reference Janicak, Davis and Preskorn1997) summarised nearly 80 studies of TCAs and 16 studies of MAOIs in the acute treatment of major depression. He concluded that the statistical likelihood of chance being responsible for the active drug-placebo difference was less than 10-40 for TCAs and less than 10-11 for MAOIs. In his meta-analysis, nearly two-thirds of patients responded to active drug, whereas about one-third responded to placebo. These analyses reveal a substantial drug effect, but many patients (one-third) continue to suffer from symptoms of depression even after vigorous treatment. Thus, the effect size is less than many would hope for.

CONTINUATION TREATMENT

The second phase of short-term anti-depressant treatment is the continuation phase. The purpose of continuation treatment is to prevent relapse, the re-emergence of symptoms, following premature withdrawal of medication after acute stabilisation has been achieved. The number of studies on continuation therapy is small compared with those on acute therapy. The key question in these studies is whether continued treatment on medication is necessary after acute stabilisation of symptoms.

Six continuation studies of TCAs, primarily amitriptyline, were identified (Table 1). Overall, less than one-fifth of those on active drug therapy relapsed compared with over half of those on placebo.

Table 1 Continuation studies in depression

| Drug | Relapse rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Active drug (%) | Placebo (%) | ||

| Studies of tricyclic antidepressants | |||

| Seager & Bird (Reference Seager and Bird1962) | Imipramine | 17 | 69 |

| Mindham et al(Reference Mindham, Howland and Shepherd1973) | Amitriptyline or imipramine | 22 | 50 |

| Prien et al(Reference Prien, Klett and Caffey1973) | Imipramine | 37 | 67 |

| Klerman et al(Reference Klerman, Dimascio and Weissman1974) | Amitriptyline | 12 | 29 |

| Coppen et al(Reference Coppen, Ghose and Montgomery1978) | Amitriptyline | 0 | 31 |

| Stein et al(Reference Stein, Rickels and Weise1980) | Amitriptyline | 28 | 69 |

| Studies of newer agents | |||

| Doogan & Caillard (Reference Doogan and Caillard1992) | Sertraline | 13 | 46 |

| Montgomery & Dunbar (Reference Montgomery and Dunbar1993) | Paroxetine | 16 | 43 |

| Feiger et al(Reference Feiger, Bielski and Bremner1999) | Nefazodone | 17 | 33 |

| Robert & Montgomery (Reference Robert and Montgomery1995) | Citalopram | 14 | 24 |

| Montgomery & Dunbar (Reference Montgomery and Dunbar1993) | Citalopram | 11 | 31 |

| Versiani et al(Reference Versiani, Mehilane and Gaszner1999) | Reboxetine | 22 | 56 |

| Ferreri et al(Reference Ferreri, Colonna and Leger1997) | Amineptine | 7 | 19 |

| Reimherr et al(Reference Reimherr, Amsterdam and Quitkin1998) | Fluoxetine | 26 | 49 |

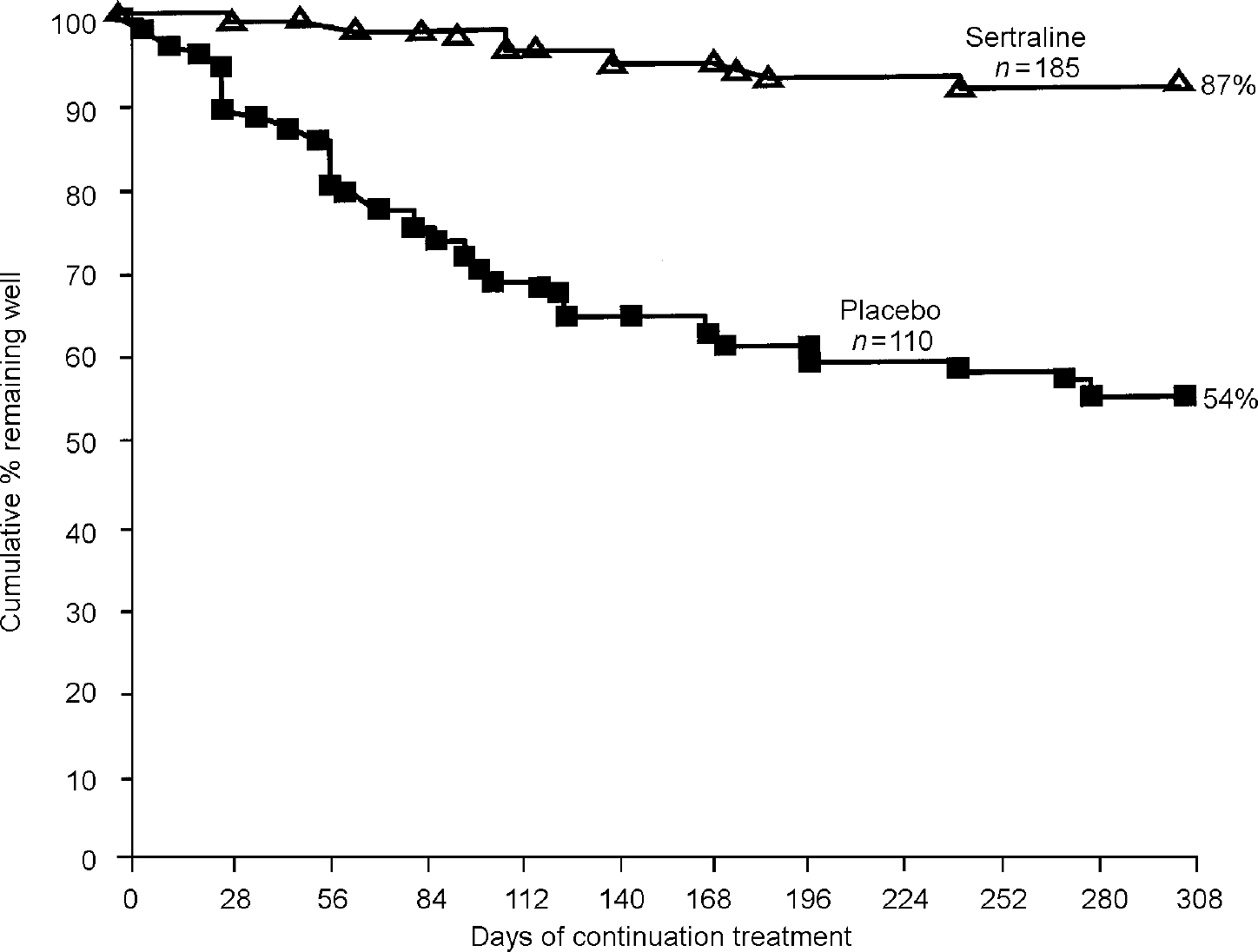

Several similarly designed studies of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other newer agents have also been conducted. For example, in an international, multi-centre study, 467 patients with major depressive disorder were enrolled in an open-label trial of sertraline for 8 weeks (Reference Doogan and CaillardDoogan & Caillard, 1992). Of the 300 responders, 185 agreed to be randomised either to stay on sertraline or to be blindly switched to placebo. After approximately 10 months of follow-up, nearly 13% of patients taking active medication relapsed compared with 46% on placebo (P<0.001) (Reference Doogan and CaillardDoogan & Caillard, 1992). Most of the relapses in this study occurred within the first 6 months of continuation treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Patients not relapsing during continuation study of sertraline. From Doogan & Caillard (Reference Doogan and Caillard1992).

Additional continuation studies involving paroxetine, nefazodone, citalopram, reboxetine, amineptine and fluoxetine, with nearly identical protocol designs, gave very similar results (Reference Montgomery and DunbarMontgomery & Dunbar, 1993; Reference Montgomery, Rasmussen and TanghojMontgomery et al, 1993; Reference Robert and MontgomeryRobert & Montgomery, 1995; Reference Ferreri, Colonna and LegerFerreriet al, 1997; Reference Reimherr, Amsterdam and QuitkinReimherret al, 1998; Reference Feiger, Bielski and BremnerFeigeret al, 1999; Reference Versiani, Mehilane and GasznerVersianiet al, 1999). Approximately one-third to one-half of patients who did not continue active treatment after stabilisation (i.e. were switched to placebo) relapsed, whereas about 15% relapsed if they continued on active medication (Table 1).

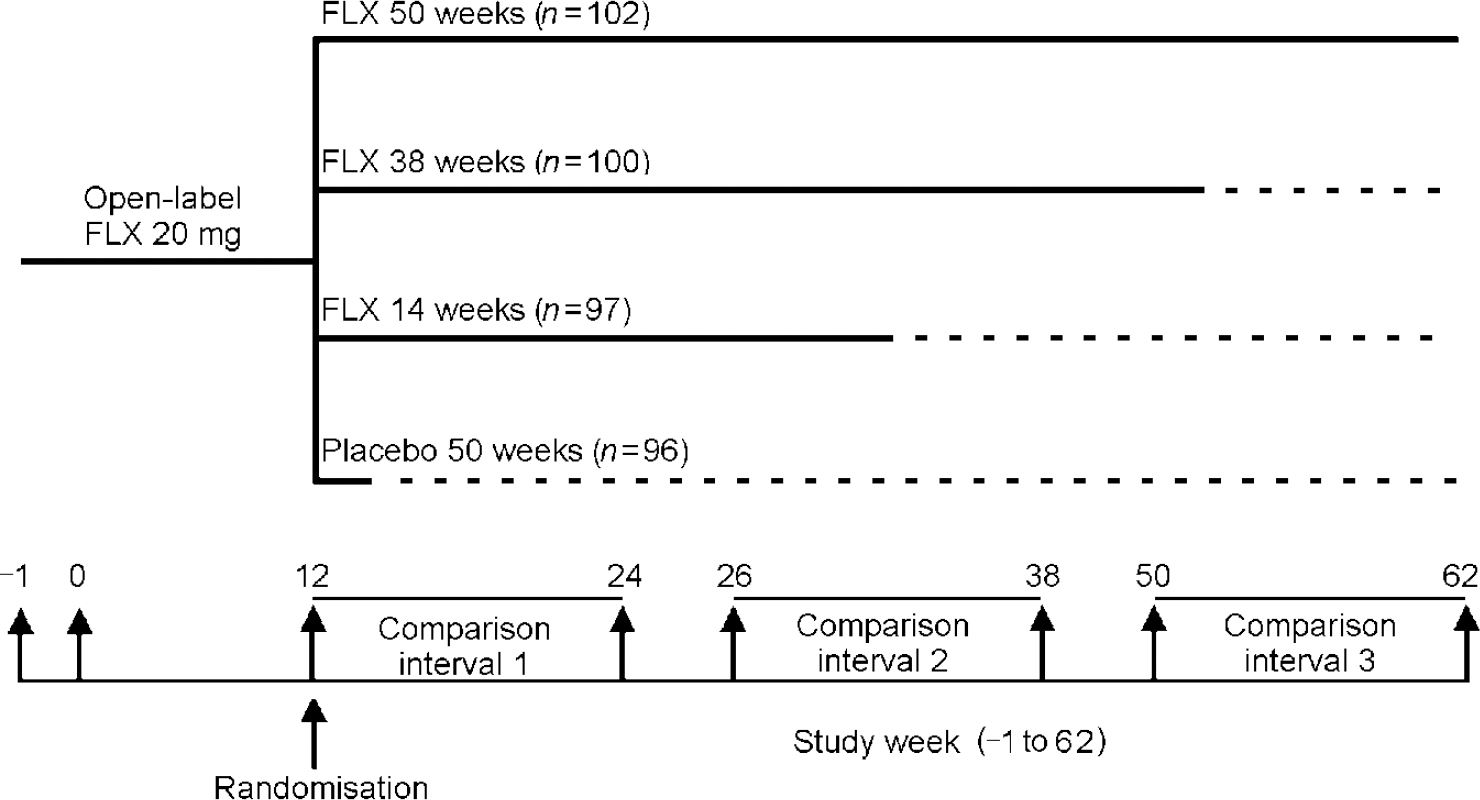

The continuation study conducted by Reimherr et al was designed to assess not only rates of relapse, but also the question of how long continuation therapy should last. Patients with major depression were treated in an open-label trial with 20 mg per day of fluoxetine for 12 weeks (Reference Reimherr, Amsterdam and QuitkinReimherr et al, 1998). Patients who had sustained remission during this period were randomised either to continue on fluoxetine or to be blindly switched to placebo. Groups of patients in the fluoxetine arm were then randomised to placebo after a further 14 or 18 weeks (for a total of 26 or 50 weeks of treatment), or were maintained on fluoxetine for the entire 50 weeks of the continuation period (for a total of 62 weeks of treatment) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Fluoxetine (FLX) continuation study design. From Reimherr et al (Reference Reimherr, Amsterdam and Quitkin1998).

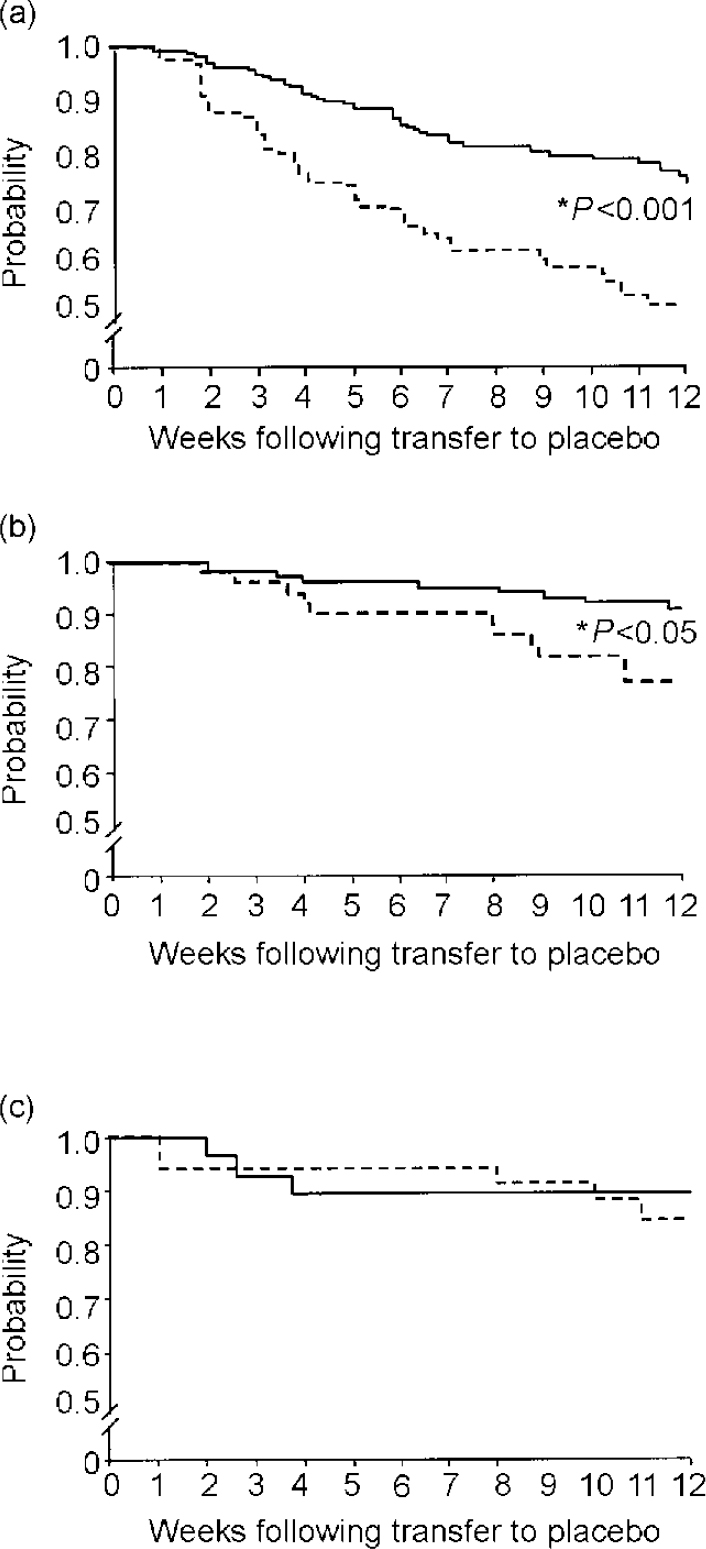

The results for the patients who were randomised at week 12 to placebo compared with those staying on fluoxetine were consistent with the earlier reported studies. Approximately 20% of those on fluoxetine relapsed, in comparison with nearly half of those on placebo (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Cumulative probability of remaining well during continuation treatment with fluoxetine (solid lines) or placebo (dashed lines). (a) Comparison interval 1 (weeks 12-24); (b) interval 2 (weeks 26-38); (c) interval 3 (weeks 50-62). From Reimherr et al (Reference Reimherr, Amsterdam and Quitkin1998).

A second group of patients were blindly discontinued at week 26 from fluoxetine. The rate of relapse for these patients (approximately 21%) was less than that found in patients discontinued at week 12 (approximately 50%), but was still significantly worse than the approximately 5% relapse rate in patients who had remained on fluoxetine throughout the 12-week period. There was no significant difference in relapse between those randomised to placebo at week 50 compared with those who stayed on fluoxetine for an additional 12 weeks (both approximately 12%). These results suggest that continuation therapy should be given for at least 3 months following remission, but in most patients need not be given beyond 9 months following remission.

In summary, results of continuation studies of both older and newer classes of antidepressant consistently demonstrate that approximately one-third to half of all patients will relapse if medication is not sustained throughout the continuation period. Only 10-15% will relapse if medication is continued. The results from the study by Reimherr et al indicate that continuation therapy should last at least 3-9 months following remission.

MAINTENANCE TREATMENT

The objective of maintenance therapy, the long-term aspect of antidepressant treatment, is to prevent the occurrence of a new episode of depression after full recovery from a previous episode. Maintenance therapy should be strongly considered for all patients at risk of recurrence. Such patients are those with a history of three or more prior episodes of major depression, pre-existing dysthymia, severe episodes, seasonal patterns, a familial history of affective disorder, a poor response to continuation therapy, and comorbid anxiety (or similar disorders) or substance misuse problems (Reference Hirschfeld and SchatzbergHirschfeld & Schatzberg, 1994).

A number of maintenance therapy studies have been performed using TCAs and one has been performed using an MAOI (Table 2). Although the recurrence rates for active drug versus placebo differ in these studies, the data consistently demonstrate a significantly higher rate of recurrence in patients given placebo compared with those who continue on active drug therapy. While these older classes of antidepressants have proven clinical efficacy, their use in the real world is hampered by concerns about side-effects (including anticholinergic, cardiovascular and histaminic effects), which can lead to non-compliance, as well as the risk of fatal overdose in patients who stockpile medication.

Table 2 Maintenance studies in depression

| Drug | Recurrence rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Active drug (%) | Placebo (%) | ||

| Studies of TCA/MAOI | |||

| Kane et al(Reference Kane, Quitkin and Rifkin1982) | Imipramine | 66 | 100 |

| Prien et al(Reference Prien, Kupfer and Mansky1984) | Imipramine | 33 | 65 |

| Frank et al(Reference Frank, Kupfer and Perel1990) | Imipramine | 20 | 90 |

| Robinson et al(Reference Robinson, Lerfald and Bennett1991) | Phenelzine | 29 | 81 |

| Old Age Depression Interest Group (1993) | Dothiepin | 40 | 60 |

| Kocsis et al(Reference Kocsis, Friedman and Markowitz1996) | Desipramine | 11 | 52 |

| Studies of newer agents | |||

| Montgomery et al (Reference Montgomery, Dufour and Brion1988) | Fluoxetine | 26 | 57 |

| Terra & Montgomery (Reference Terra and Montgomery1998) | Fluvoxamine | 13 | 35 |

| Keller et al(Reference Keller, Kocsis and Thase1998) | Sertraline | 6 | 23 |

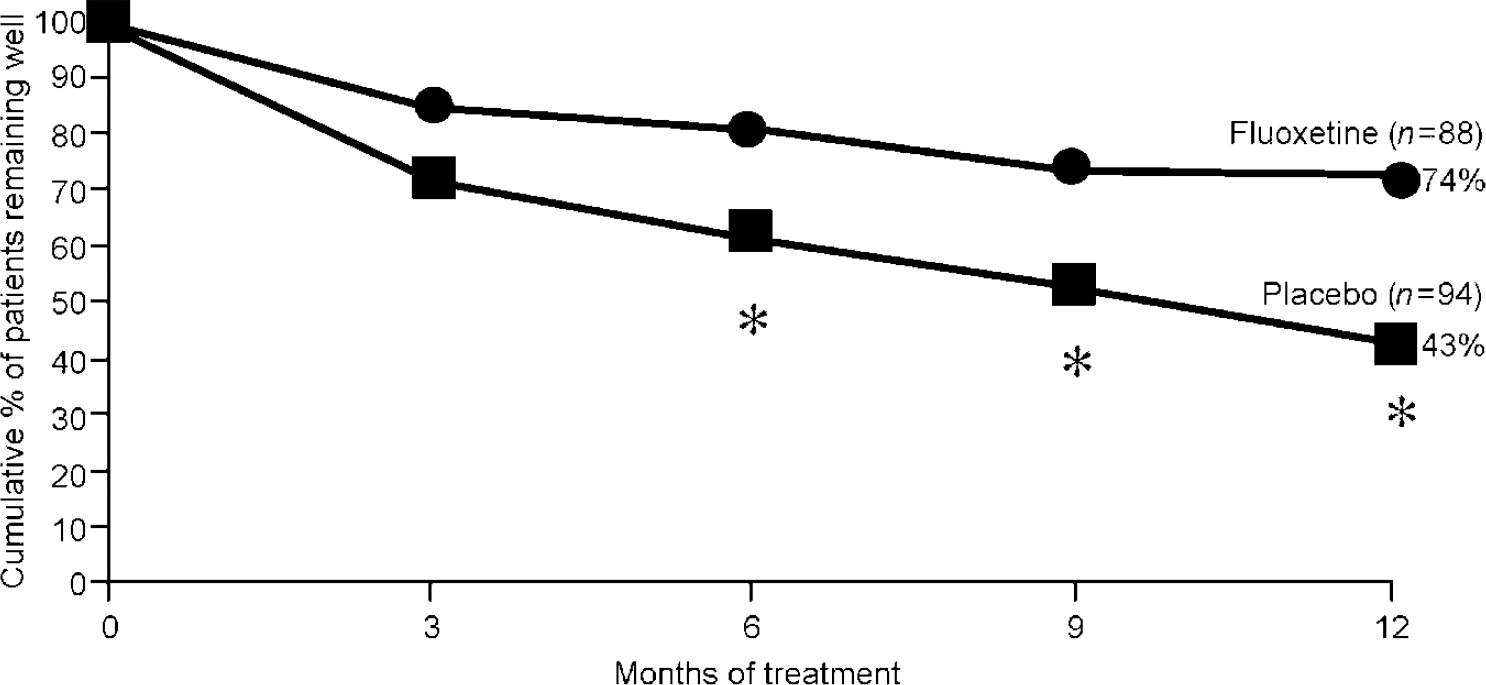

Maintenance studies involving the SSRIs fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and sertraline have also been performed. In one study, 456 patients with DSM—III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) recurrent major depression were treated with open-label fluoxetine for 6 weeks (Reference Montgomery, Dufour and BrionMontgomery et al, 1988). Those who responded were continued on fluoxetine therapy for an additional 18 weeks. Those who completed this 24 weeks of treatment were randomised to continue with fluoxetine (n=88) or to switch blindly to placebo (n=94). Recurrence of depression was defined by a score above 18 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1967). A recurrence rate of 26% occurred in the fluoxetine group during the 1-year follow-up compared with 57% in the placebo group (P<0.001) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Patients without recurrence of depression during 1-year maintenance study; * P<0.01. From Montgomery et al (Reference Montgomery, Dufour and Brion1988).

A similarly designed study using fluvoxamine gave results consistent with those observed in the fluoxetine study. A mean daily dose of 100 mg of fluvoxamine was shown to be effective in preventing recurrence of DSM—III—R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) major depressive disorder. Recurrence was defined as a reappearance of depressive symptoms in the opinion of the investigator. The fluvoxamine group had a recurrence rate of 13%, whereas the placebo group had a recurrence rate of 35% (P<0.001) (Reference Terra and MontgomeryTerra & Montgomery, 1998).

The studies described above and summarised in Table 2 suggest that, among patients at risk, depression will recur in approximately 60% within 1 year if untreated. If patients continue to receive treatment with newer antidepressants, the recurrence rate drops to between 10% and 30% (Table 2). This clearly supports the efficacy and advisability of maintenance treatment if patients are among those at risk.

CONCLUSION

Depression is a recurrent and often a lifelong illness, which requires long-term treatment. The notions prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s that depression could be treated successfully within a period of weeks have been modified in the light of substantial evidence to the contrary. All patients with major depression who have successfully responded to an antidepressant drug should be continued on medication for a period of 3-6 months beyond acute symptom resolution. If not, up to half of them will relapse back into their original episode. Patients at risk of recurrence should be considered for maintenance therapy. Such patients will almost certainly experience a recurrence of depression within several years without continued treatment.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.