Background to the case study

CBT based on a self-regulation model (SR-CBT) is a cognitive behavioural therapy for difficult-to-treat depression (McAllister-Willams et al., Reference McAllister-Williams, Arango, Blier, Demyttenaere, Falkai, Gorwood, Hopwood, Javed, Kasper, Malhi, Soares, Vieta, Young, Papadopoulos and Rush2020; Rush et al., Reference Rush, Sackeim, Conway, Bunker, Hollon, Demyttenaere, Young, Aaronson, Dibué, Thase and McAllister-Williams2022). The model and treatment components are described in a concurrent article (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Robinson and Bromley2022) and readers are encouraged to read that article for more details about the theoretical framework and how the treatment components are derived from it. The aim of this article is to illustrate the application of SR-CBT in a difficult-to-treat case of depression, in particular how the treatment components were organized and delivered, and how these influenced the process and outcome of therapy. SR-CBT has 10 treatment components and a key part of the approach is individualizing therapy based on the case formulation. Individualizing means varying the sequence, combination and dose of the treatment components, based on client need – it does not mean drifting from the therapist actions prescribed in the components.

The client in question was an active participant in the research process. She suffered from highly recurrent depression, with atypical mood fluctuations, and had received several treatments over the previous 13 years, including anti-depressant medication, computer-assisted CBT, counselling, psychodynamic psychotherapy, group-based mindfulness-based CBT, individual CBT, and intermittent care from a community mental health team and crisis team. She had received temporary but not lasting benefit from these interventions, gaining support, psychoeducation and coping skills, but not lasting remission from depression. She concurred that her depression was difficult to treat, acknowledging that there had been difficulties for both her and her previous therapists. Following assessment at the Centre for Specialist Psychological Therapies, the client was given the choice between a further course of standard CBT and a course of SR-CBT. She was given information, had an opportunity to ask questions and chose SR-CBT, explaining that the previous CBT been helpful but not lasting, and she would prefer to try a novel treatment.

At the time of the assessment, the client had been keeping a daily mood diary over the previous 16 months (514 days), during which time she had received a course of standard CBT (15 sessions), anti-depressant medication (ADM) and support from a community mental health team (CMHT). The daily diary created an opportunity for a baseline phase against which the SR-CBT could be compared and tested. The opportunity for a quasi-experiment was only recognized at this point, so the case study was limited to the mood measure that the client had been using in her previous care. The sequence of SR-CBT delivered after CBT, ADM and CMHT was not randomized or open to experimental control. Nevertheless, this case study is a good example of naturalistic practice-based evidence, with a high level of collaboration and participation from the service user. She recognized the value of continuing to complete the mood diary as a way of comparing SR-CBT with previous treatments, and was supportive of her treatment being summarized in this article, taking an active role in ensuring confidentiality within the write-up (several personal details are anonymized). She declined the opportunity to be a co-author but provided feedback on drafts and was satisfied with how the therapy had been summarized and discussed. The first author (S.B.) was the therapist, and he received monthly supervision throughout from the second author (P.A.).

Demographics and mental health history

Evelyn (psydonym) was a 52-year-old married woman with two grown-up daughters from a previous marriage. She first presented to mental health services aged 39, diagnosed with recurrent depressive disorder. She reported occasional episodes of depression as an adolescent that became more frequent and problematic in her late 20s and 30s. Evelyn’s marriage broke down when she was 42 and this precipitated an intense experience of personal failure, a severe depressive episode and a serious suicide attempt. In the subsequent 10 years, Evelyn experienced intermittent severe depressive episodes within the same phasic pattern. During periods of milder depression, Evelyn could be energized and engaged in her work as managing director of a company. These phases fell short of the threshold for hypomania: bipolar II disorder was not diagnosed, but psychiatric evaluation suggested an atypical phasic pattern of alternating mild, moderate and severely depressed moods with a high level of unpredictability from one day to the next.

Treatment phases

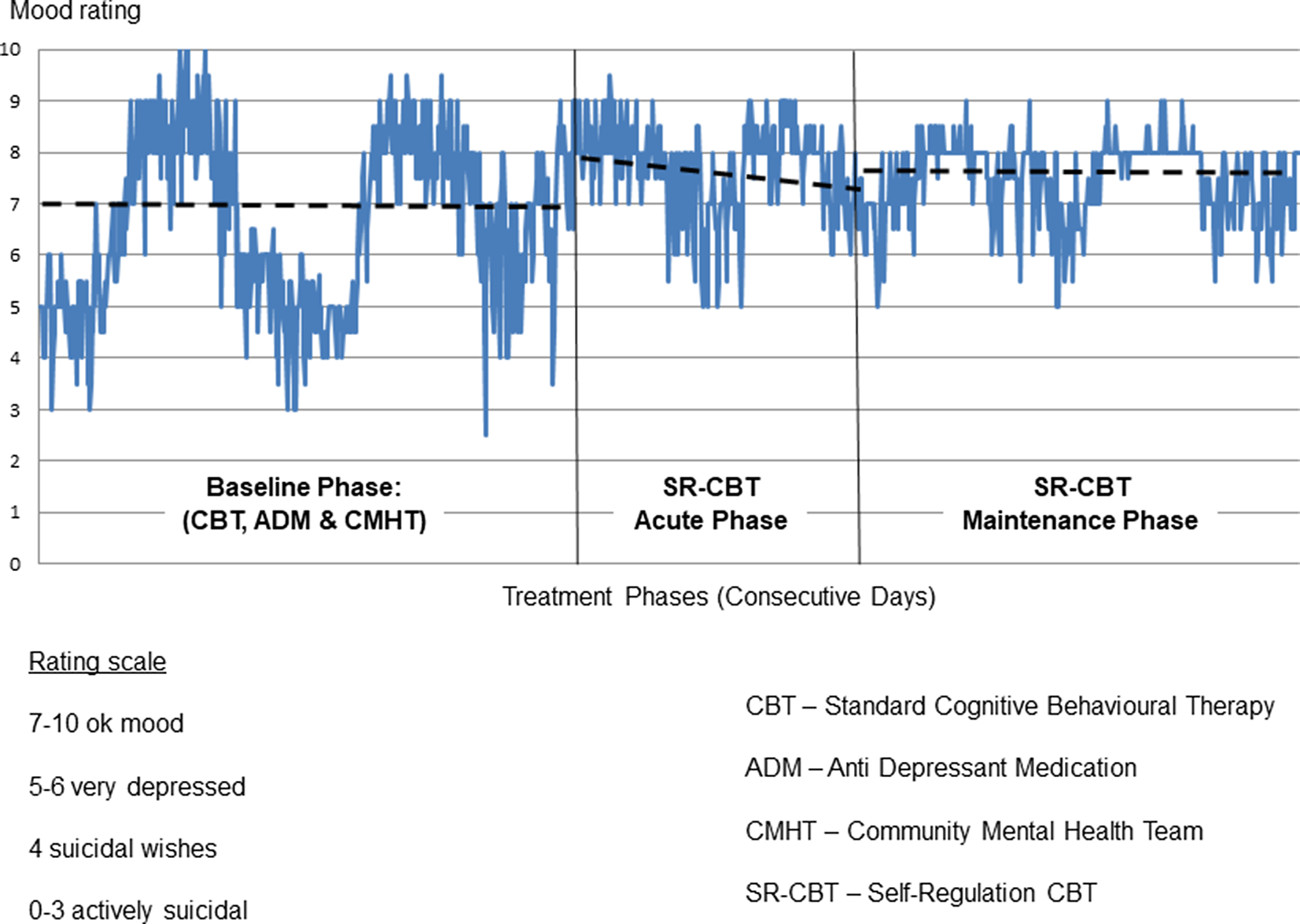

Up to 30 sessions is the usual dose of SR-CBT for clients with difficult-to-treat depression, and Evelyn received 27 sessions of SR-CBT over a 10-month acute phase (306 days). Her pre-treatment Patient Health Questionnaire score was 19 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) indicating moderate depression symptoms, and her GAD-7 score was 5, confirming depression as the primary problem (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). Evelyn’s moods were subject to a lot of fluctuations and this pattern is depicted in a graph of her daily mood ratings (Fig. 1). The ratings were made on the following 11-point scale, with higher numbers representing milder depression: 7–10, OK mood; 5–6, very depressed; 4, suicidal wishes; 0–3, actively suicidal.

Figure 1. Evelyn’s daily mood ratings across treatment phases.

Evelyn was at heightened risk of relapse due to adverse childhood experiences, early onset depression, multiple previous episodes and unstable remission (Bockting et al., Reference Bockting, Hollon, Jarrett, Kuyken and Dobson2015). For this reason, she was offered a maintenance phase of monthly booster sessions after the acute phase was completed, with the goal of maintaining progress and staying well (Jarrett et al., Reference Jarrett, Kraft, Doyle, Foster, Eaves and Silver2001). This was initially expected to last 6 months, but it was extended to 15 months (15 sessions, 463 days) to accommodate Evelyn’s learning process and heightened risk. Evelyn continued to take anti-depressant medication and have intermittent CMHT support during both phases of SR-CBT.

Treatment process

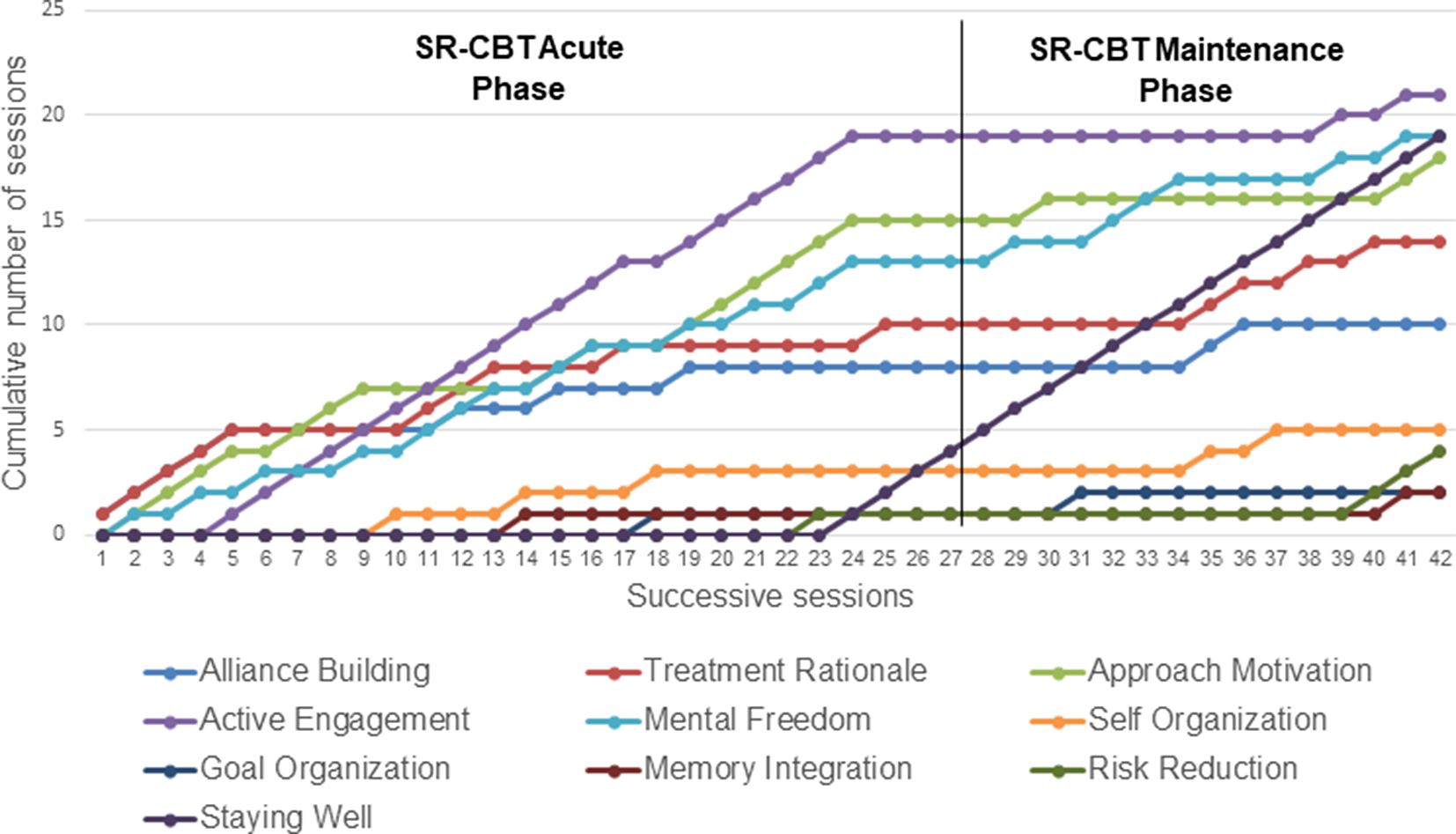

Emphasis was placed on the self-regulation skills that Evelyn most needed to develop, based on her case formulation. To provide an overview of when and how the components were delivered, the acute and maintenance phases have been combined in the following summary. The number of sessions in which each component formed a significant part are presented in a cumulative plot in Fig. 2. Sessions usually combined more than one treatment component (mean = 2.77 per session). The way each component was delivered, and the number of sessions in which they formed a part, are described below.

Figure 2. SR-CBT treatment components: cumulative number of sessions in which each component was delivered.

Alliance building (10/42 sessions)

An effective working alliance was established with Evelyn over the first five sessions. She was trusting and respectful and the personal alliance formed easily. The task alliance, reflected in alignment on target problems, goals and therapy tasks, was more challenging to develop, and there were three barriers (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Wicks, Freeman and Meyer2017; Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Rodgers and Dagnan2018). Firstly, Evelyn was ambivalent about receiving further CBT and unsure whether it would differ from her previous therapy. Her initial motivation came from a sense of obligation to her husband, who encouraged her to try new therapies. Evelyn was not optimistic that SR-CBT would produce benefits that were different or greater than previous therapies. Secondly, Evelyn’s mood disorder was highly persistent with several recurrent major episodes and an atypical pattern of mood fluctuations. Even if she responded to SR-CBT, she would have heightened risk of relapse (Wojnarowski et al., Reference Wojnarowski, Firth, Finegan and Delgadillo2019). Thirdly, Evelyn had suffered adverse childhood experiences in her birth family for which she felt partly responsible. She felt uncomfortable discussing herself, and was particularly reluctant to discuss early experiences in case she was perceived to be blaming her parents.

The therapist’s response was to guide discovery about each of these issues, making them explicit and investing time to reach an aligned position. The therapist sought to differentiate SR-CBT from standard CBT, encouraging Evelyn to find out if it was similar or different by committing to a small number of sessions initially. This increased Evelyn’s agency to engage in the therapy, without the therapist taking too much responsibility for change. The therapist also emphasized the need for two phases of treatment, the first to improve Evelyn’s mood and the second to sustain those changes. The risk of relapse was acknowledged at the outset, with a pro-active approach emphasizing that staying well depended on applying self-regulation skills that could be learned during treatment. Finally, the therapist acknowledged that a strong relationship was needed to discuss painful childhood experiences, and Evelyn did not need to decide at the start of therapy whether she wanted to do this later. These conversations had an alliance-strengthening effect, sufficient to proceed with the other treatment components. Throughout treatment, the therapist had to be robust in maintaining the task alliance to keep the therapy sufficiently change-focused.

Treatment rationale (14/42 sessions)

The treatment rationale in SR-CBT is to reflect on mood fluctuations, differentiating depressed and less-depressed moods and using this to leverage change. Depressed moods help to formulate how depression is maintained; less-depressed moods help to find a path out of depression. Evelyn readily accepted that there were a lot of fluctuations in her moods. She found it particularly frustrating, and bewildering, that her moods could plummet from mild to severe in a short space of time with no apparent trigger. She accepted the logic that less-depressed moods could help to find a path out of depression, but in practice she would default to discussing depression, trying to find out what had triggered it so that she could avoid those triggers. Avoiding triggers was one of the strategies she had learned in previous treatments. In Evelyn’s case, this strategy was maintaining behavioural avoidance and rumination (e.g. ‘why do these keep happening?’). She gradually accepted that she could not always discover what the triggers were, and also came to realize that avoiding triggers was not the best strategy, because they were difficult to predict and attempting to do so maintained an avoidant orientation: trying to dodge undetermined hazards, rather than influencing situations in a preferred direction (Quigley et al., Reference Quigley, Wen and Dobson2017).

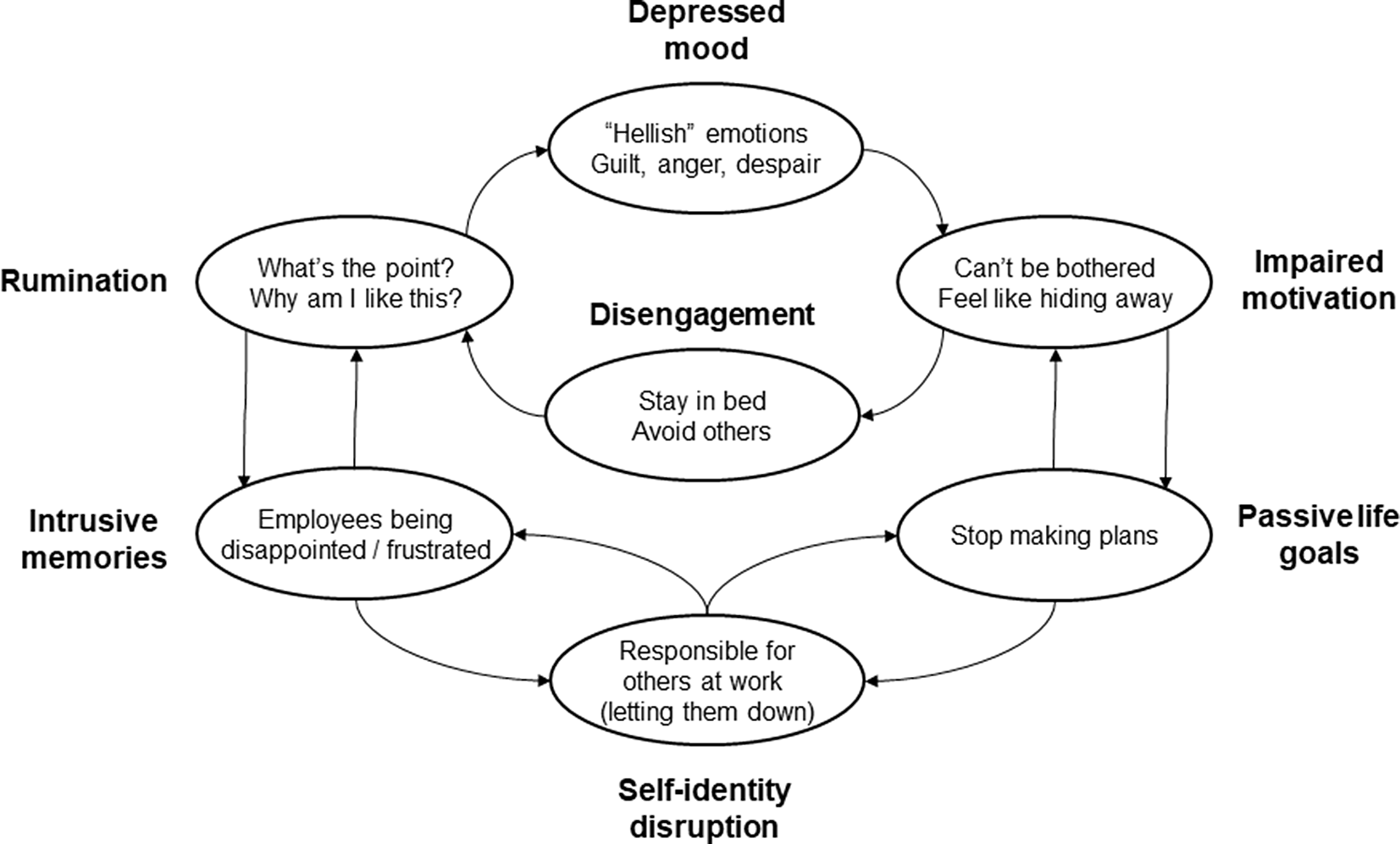

Over the first five sessions, Evelyn was socialized to key features of the self-regulation model. The model proposes that depression is perpetuated by repeated interactions of self-identity disruption, impaired motivation, disengagement, rumination, intrusive memories and passive life-goals. The repeated interaction of these processes maintains depression like a traffic gridlock (Barton and Armstrong, Reference Barton and Armstrong2019; Teasdale and Barnard, Reference Teasdale and Barnard1993). Figure 3 presents Evelyn’s formulation which was built up over several sessions.

Figure 3. Evelyn’s case formulation.

Evelyn’s self-identity was narrowly invested in taking responsibility for others through her work as a managing director. This was a positive self-representation in the sense that it provided self-definition, value and purpose. Evelyn ascribed importance to doing her job well and was highly invested in that goal. This does not mean that she had consistently positive beliefs about doing a good job; in fact, these fluctuated a great deal. She experienced phases of work going reasonably well when she reported her mood to be ‘OK’, but small setbacks at work (real or perceived) had a disproportionate effect on her mood. She could switch rapidly into a self-loathing, unmotivated, withdrawn, ruminative state, pre-occupied with memories of letting others down and uninterested in planning for the future. When Evelyn’s depression was milder, she would engage in work tasks with some interest and a felt-sense of obligation, sometimes over-working, joining in with others and experiencing some job satisfaction. She recognized that her attention was more externally focused on these occasions, and she was more able to think clearly and make decisions.

The treatment rationale was revisited regularly throughout therapy, particularly when Evelyn suffered setbacks and became despondent about change. When this happened, the therapist would re-focus attention on less-depressed moods and encourage Evelyn to keep influencing her motivation, actions and cognition. To effect change, sufficient emphasis has to be placed on less-depressed experiences, and to achieve this the treatment rationale usually has to be revisited regularly.

Approach motivation (18/42 sessions)

Approach motivation is often delivered in combination with active engagement (see below). The aim is to stimulate approach impulses which are usually attenuated during depression with reduced positive anticipation, lower reward expectancies and weakened interest in desired outcomes (Sherdell et al., Reference Sherdell, Waugh and Gotlib2012). When reflecting on Evelyn’s less-depressed moods, the therapist questioned her motivational impulses and intentions; for example, when she felt some satisfaction after a particular work meeting. This increased the explicitness of Evelyn’s desires to support the staff that worked in her company, to whom she felt very responsible. Rather than focusing on responsibility beliefs, the therapist asked what Evelyn would like to happen in her organization, and how she would like key staff to develop. These desires were elaborated in a lot of detail and they helped to generate reasons for action; for example, to influence work culture and strategic direction.

Another example was bringing attention to what Evelyn needed when she felt negative emotions; for example, upset, guilt, sadness or anger. Her tendency was to suppress negative emotions because they would often activate depressing thoughts and provoke rumination. She had not considered emotions as signalling needs, for example, the need for self-soothing, forgiveness, support, grieving, communication, fairness, etc. Evelyn was not accustomed to reflecting on her needs and desires in this way, initially appraising it as selfish. This was unfamiliar and uncomfortable for her – even dystonic at times – and took a long time to make sense and sit more comfortably. Attending to needs and desires is self-compassionate: it signals the value of responding to one’s suffering and attempting to alleviate it, and of taking desires seriously and wanting to realize them. Repeated attention to Evelyn’s needs and desires helped to generate reasons for action and, over an extended period, reasons to act gradually became impulses for action.

Active engagement (21/42 sessions)

The goal of active engagement is to increase clients’ interaction with tasks and other people, with engagement targeted in situations where the client tends to disengage, withdraw and/or avoid (Ottenbreit et al., Reference Ottenbreit, Dobson and Quigley2014). There is a big emphasis on experimentation, with clients encouraged to try out new ways of interacting, including how they relate to themselves. The focus is on setting goals to influence preferred outcomes and aligning those goals with needs and desires. Consequently, the output of approach motivation is often used to plan experiments within active engagement.

In Evelyn’s therapy, 50% of the sessions involved planning a behavioural experiment to be conducted before the next session, and this would often relate to a work commitment that Evelyn’s secretary had booked in, or a personal engagement that her husband had arranged for them. It was normal for Evelyn to be dreading these and feel like withdrawing from them. From session 6 onwards, the repeating therapeutic pattern was exploring prospectively what Evelyn would like to happen in those situations. Time was taken to plan how she wanted to approach the situation, emphasizing how she would interact and communicate with others, to try to influence what she would like to happen. She would also consider which mindset she needed to be in before, during and after the situation, in particular where to place her attention and how to keep preferences in mind. Sessions would end with Evelyn stating her preferred outcomes, not her predictions, and the experiment was to find out if and how she could influence those preferences. A de-brief was planned for the next session.

Examples include feeling despondent about not having sufficient administrative support in her office, even though she was the managing director of the company. When feeling depressed, it did not occur to Evelyn that she had the authority and influence to hire more staff, imagining that this would be blocked by red tape that was out of her control. The therapist dis-attended to Evelyn’s negative predictions and kept attention on what she would like to happen in this situation. With some reluctance and difficulty, Evelyn slowly worked back from the desired outcome and, over a number of weeks, the staffing was increased. Another example was dreading a visit to see her elderly parents, feeling like cancelling on the pretence of ill-health. The therapist enquired about the best and worst memories of visiting her parents, and this helped Evelyn to identify what she was most dreading: feeling trapped in their home, unable to leave (see self-organization section). By staying focused on what she would like to happen (e.g. having her own space, going out when she wanted), Evelyn developed a plan to stay in a local hotel and let her parents know in advance that she was increasing physical exercise. These possibilities had not previously occurred to Evelyn, and overall they contributed to a more tolerable family visit.

Evelyn struggled with active engagement for several months, preferring to talk about negative experiences that had occurred in the previous week, and was sometimes frustrated that the therapist did not pay much attention to her negative predictions. The personal alliance was sufficiently strong to withhold this, so the therapist kept the task alliance as the priority (i.e. change-focus). After 6 months of slow learning, a threshold was reached and Evelyn started to internalize the active engagement process that she had applied across several experiments. When she paid attention to her preferred outcomes, and formed an intention to bring them about, she was usually able to influence them in some way, even if it was not in the way she had expected.

Mental freedom (19/42 sessions)

The aim of mental freedom is to develop a good self-mind relationship with reflective capacity, attentional skills and productive questioning. The first step is to increase awareness of the difference between rumination and reflection and this occurred in the first six sessions when the treatment rationale and initial formulation was developed. Evelyn accepted that rumination was unhelpful but she did not always recognize when it was happening (Watkins and Roberts, Reference Watkins and Roberts2020). When her mood lifted, she was usually able to reflect back on her experiences and recognize that rumination had occurred. It took several months for Evelyn to become aware of rumination when it was happening in the moment, and then she felt minimal control over it. As her reflective capacity increased, Evelyn developed more attentional skills. This grew out of the recognition that she tended to be self-focused in depressed moods and more externally focused in less-depressed moods. External focus of attention became a regular part of active engagement. This gradually gave her a tool to use when feeling more depressed, choosing to place her attention externally, when she remembered to do so. This was not sufficient to prevent all depression and rumination, but it had a beneficial effect and was the beginning of Evelyn learning how to influence her cognition during depressed moods.

The intervention that had greatest impact was recognizing the unhelpfulness of the questions she asked herself when feeling depressed, such as: ‘what’s the point?’, ‘why bother?’, ‘why can’t I be normal like everyone else?’, etc. These thoughts indicated how distressed, frustrated and angry Evelyn could become with herself. When her mood was less depressed, Evelyn brought these questions to mind in cognitive experiments within therapy sessions: the presence of the questions depressed her mood, brought negative thoughts to mind and led to unhelpful answers. Evelyn recognized their unhelpfulness, but didn’t know how to think differently, especially when feeling depressed. With the therapist’s guidance, she was able to experiment with different types of question such as ‘how can I help myself right now?’, ‘what do I need to do next?’, ‘who can I talk to?’. Evelyn recognized that these were more helpful, concrete and practical questions, giving her ideas for action, and that this was a better way to respond when feeling down. She started monitoring her questions at work, particularly when feeling burdened or guilty, and there was a gradual shift from less to more helpful questioning (e.g. ‘why do I keep messing up?’ became ‘did I make a mistake?’). The challenge was helping Evelyn to access reflective thinking when she most needed it, when her mood was 6/10 or less. Initially she was only able to apply these skills when her mood was 7/10 or greater, and this became one of the key aims of relapse prevention and staying well.

Self-organization (5/42), goal organization (2/42) and memory integration (2/42 sessions)

In the self-regulation model, vulnerability to depression results from the under-development of positive self-representations and their associated self-regulatory capacities, rather than the presence negative beliefs. The main aim of self-organization is to strengthen, diversify and re-structure positive self-representations. The main aim of memory integration is to elaborate positive recollections to increase their memorability and accessibility, when possible making explicit links to positive self-representations. The main aim of goal-organization is to structure life-goals so they are approach-based, concrete, imaginable and span a range of self-representations.

The main hypothesis about Evelyn’s vulnerability to depression was that her early family experiences limited the development of positive self-representations and associated life skills. When growing up, Evelyn endured several years of marital discord, conflict and miscommunication, with her parents unaware of its psychological impact on her. As time passed, Evelyn felt increasingly responsible for her family’s unhappiness, unable to solve her parents’ difficulties. She internalized a lot of unhappy memories and often felt helpless, unable to escape or improve the family situation. Her parents’ dissatisfaction with each other captured much of their attention, and Evelyn’s need for emotional support, encouragement and soothing was often overlooked.

This was compensated, to some degree, by her intelligence and aptitude at school where she was responsible, hard-working and successful, but her capacity to encourage herself and self-soothe was not consistently supported at home. On the contrary, the family atmosphere was characterized by criticism and harshness, which came to reflect Evelyn’s relationship with herself. Being responsible, intelligent and hard-working led to a successful path through school, university and her subsequent career, but her positive self-representations were few in number, narrowly invested in feeling responsible to others, particularly in her role as a managing director. This brought her a lot of career success and some periods of euthymic mood, but she had limited resilience to buffer negative interpersonal experiences when, as she perceived it, she made mistakes or let others down. As we have already observed, when her self-identity as a responsible managing director was disrupted Evelyn could switch rapidly into self-attack, self-blame and self-loathing.

Focusing on personal qualities was very challenging for Evelyn because she was very uncomfortable receiving positive feedback; it jarred as if it had no place within her. Throughout therapy, the therapist would comment on Evelyn’s good humour, compassion, intelligence and work expertise, in an attempt to strengthen her acceptance of these qualities, but this was limited by Evelyn’s reluctance to participate in this type of change. It is possible that Evelyn would have benefited from greater therapeutic focus on her memories, self-identity and life-goals, but throughout therapy she remained uncomfortable discussing herself, her early life in particular, and this limited the depth of self re-organization that was possible.

Risk reduction (4/42 sessions)

The aim of risk reduction is to reduce suicide risk when it is increased. Clients’ motives are explored in detail by asking about the intended and unintended consequences of suicidal actions. When feeling suicidal, clients’ attention often narrows around a specific need, for example, to be re-united with a loved one, to escape, to experience relief or put an end to a particular feeling. Evelyn’s mood rating did not enter the suicidal range (4/10 or less) during the course of SR-CBT, but there were occasions when she was bothered by suicidal thoughts, and on those occasions the therapy helped her to explore the goal of suicide: what did Evelyn imagine suicide would achieve? In Evelyn’s case, she believed it could result in ‘an end to hellish feelings’ and ‘not having to be me anymore’. This was tempered by potential unintended consequences, including pain, injury, illness and her husband being devastated. Evelyn recognized an inner battle between these pros and cons that she had lived with over several years.

The therapy tried to broaden Evelyn’s attention onto other life-goals and reasons for living, including seeing her company grow, supporting the development of key colleagues and enjoying holidays with her husband (Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Goodstein, Nielsen and Chiles1983). Most importantly, it tried to identify non-lethal ways to respond to her felt-need to avoid ‘hellish’ emotions and escape herself. The main strategy was to encourage Evelyn to switch from avoidance to approach. Rather than avoid these feelings, she was encouraged to influence them so they occurred less frequently and respond to them differently when they were present. Rather than escape herself, she was encouraged to submit to a deeper acceptance of her personal qualities. Some of this therapeutic work was acutely uncomfortable for Evelyn, but it appeared to contribute to her increased safety over the course of the treatment.

Staying well (19/42 sessions)

Towards the end of the acute phase, four sessions of staying well were provided, aiming to consolidate the skills Evelyn had learned during therapy and apply them more independently (Jarrett et al., Reference Jarrett, Kraft, Doyle, Foster, Eaves and Silver2001). There remained an unpredictability in Evelyn’s moods that was frustrating and difficult for her to accept, and when her mood was more depressed (i.e. 6/10 or less) it was very difficult for her to remember and apply skills she had learned. It became apparent that this was a significant struggle for Evelyn, and this was what prompted the offer of maintenance therapy. This was initially expected to be monthly for 6 months, but it was extended to 15 months, reflecting the size of the task. There were two main aims: (a) to make Evelyn’s self-regulation skills more explicit and memorable; and (b) to help her access the skills when they were most needed, during depressed moods (i.e. 6/10 or less). Evelyn’s understanding of what she needed to do to stay well gradually became more explicit, and her skills became more automatic, but this was very slow learning that relied on multiple repetitions to become accessible during depressed moods.

Treatment outcomes

By the end of the acute SR-CBT phase, Evelyn’s PHQ-9 score had reduced from 19 to 2. This is a reliable change of more than 6 points that is also below the threshold for clinical caseness (McMillan et al., Reference McMillan, Gilbody and Richards2010). However, a pre–post comparison only takes account of two time-points and cannot capture the dynamics of mood patterns or changes within them. The daily mood ratings provided a richer description of those dynamics and also allowed comparisons between phases. The main questions were: (a) whether moods in the acute phase of SR-CBT were less depressed and more stable, compared with baseline; and (b) whether changes in mood during acute phase SR-CBT were sustained in the maintenance phase. Visual analysis of Fig. 1 confirms that there was a lot of variability within each phase, consistent with Evelyn’s formulation. A cyclical pattern was apparent, both within and across phases, with apparently milder depression and more stable mood during the SR-CBT phases (baseline median = 7; acute SR-CBT median = 8; maintenance SR-CBT median = 8). Evelyn’s risk was also less during SR-CBT: she scored 4 or less (indicating suicidal wishes) on 24/514 days during the baseline phase (4.6%) and 0/769 days during SR-CBT (0%).

Differences between phases were tested statistically using non-overlap methods (Morley, Reference Morley2017; Parker and Vannest, Reference Parker, Vannest, Kratochwill and Levin2014; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Vannest, Davis and Sauber2011). There was no significant trend within the baseline phase when Evelyn received standard CBT, ADM and CMHT (Tau-U=–0.028, Z=–0.963, p=0.336). The same underlying mood pattern was recurring without a significant trend towards better or worse mood, and this is reflected in the flat trend line in the baseline phase in Fig. 1. There was therefore no need to control for baseline trend in the comparison with acute phase SR-CBT, which revealed a statistically significant improvement in mood, consistent with Fig. 1 (Tau-U=0.257, Z=6.167, p<0.001). Compared with baseline, Evelyn’s moods were significantly milder during acute SR-CBT, but there was also a significant decreasing trend during the acute phase which, without further intervention, could have led to relapse (Tau-U=–0.151, Z=–3.934, p<0.001). This is depicted in the sloping trend line in the acute phase in Fig. 1. With this trend statistically controlled, there was a significant difference between acute phase SR-CBT and maintenance phase SR-CBT, favouring the maintenance phase (Tau-U=–0.093, Z=–2.192, p=0.028). Evelyn’s mood was more stable in the maintenance phase, with no significant trend for worsening or further improvement (Tau-U=–0.035, Z=–1.114, p=0.265). This is reflected in the flat trend line in the maintenance phase in Fig. 1.

Discussion

This single case demonstrates how SR-CBT is organized and delivered across a course of therapy. Because Evelyn kept a mood diary over an extended period, comparisons could be made between treatment phases. The case demonstrates the aim of SR-CBT: to provide effective therapy for difficult-to-treat clients who have received standard CBT in the past but where it has not had a beneficial or lasting effect (Barton and Armstrong, Reference Barton and Armstrong2019). The pattern of results is consistent with the model’s claims, that SR-CBT can provide an effective alternative when standard CBT has not been sufficiently potent (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Robinson and Bromley2022). There are alternative explanations for the changes observed during SR-CBT, for example, that positive life events or other treatments were responsible for the effects. However, Evelyn attributed the changes to SR-CBT; there were no major positive life events during the 25 months of her treatment; she continued to take anti-depressant medication and receive CMHT support, but there were no substantial changes in medication and, due to her improvement, CMHT input was less than before.

Assuming that the changes are at least partly attributable to SR-CBT, this case does not provide evidence that SR-CBT is more effective than standard CBT; it does not address that question. The case is illustrative and not a comparative test: it is one case, without randomization or replication. A scientific comparison of cognitive therapy vs behavioural activation vs SR-CBT would need to balance the order in which they were received, since Evelyn’s gains during SR-CBT could be partly attributable to the preparatory effects of previous therapy. It would also need to match treatment doses and use a broader range of measures: 42 sessions is significantly greater than 15 sessions, which was the dose of the standard CBT she received in the baseline phase. Nevertheless, what can be claimed is that, in this particular case, high dose SR-CBT coincided with positive changes in mood that did not occur during standard CBT at a normal dose, and these changes were sustained over a 15-month maintenance phase. The enduring effect of SR-CBT in this case echoes the lasting benefits reported in an earlier version of this treatment (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Freeston and Twaddle2008).

Although a single case is limited without replication, single case methods have the potential to address issues in the field that are normally approached through randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. For example, the bespoke combination of treatment components is open to empirical scrutiny to find out how much variance occurs across cases, and whether the same or different ingredients are associated with better outcomes. If it is the same ingredients, SR-CBT could become more protocolized in the future; if it is different ingredients, there is a case for continued individualization with this client group. Repeated measure designs also have the potential to detect trends that are not usually measured in RCTs, the best example in this study being the decreasing trend in the acute SR-CBT phase, even though this phase had significantly milder depression than the baseline. If this pattern was replicated in other cases, it could be a way of detecting empirically which cases are at greater risk of relapse through their response to acute phase treatment.

Two further questions need to be addressed. Firstly, how similar or different is SR-CBT compared with standard CBT? Therapists use core CBT skills to provide SR-CBT and it certainly has overlaps with other CBT treatments, for example, mental freedom shares features with rumination-focused CBT (Watkins and Roberts, Reference Watkins and Roberts2020), and active engagement shares features with behavioural activation (Martell et al., Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobsen2001; Martell et al., Reference Martell, Dimidjian and Herman-Dunn2010) and activity scheduling in cognitive therapy (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). Readers are encouraged to access the concurrent article that explores these similarities and differences in more detail (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Robinson and Bromley2022).

Secondly, are the effects of SR-CBT attributable to high dose treatment rather than specific treatment components? This possibility cannot be ruled out, but the change pattern depicted in Fig. 1 suggests a specific response to SR-CBT, rather than a simple dose effect. However, this question needs to be addressed through replication in further studies, and the health economics of high dose treatment also need consideration. Arguably, an effective high dose treatment for difficult-to-treat cases would save resources in the long term, given the healthcare costs incurred by treatment-resistant depression (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Powell, Anderson, Szabo and Cline2019). For some clients, fast learning is not possible and slow learning across a high intensity treatment may be more cost-effective than subsequent multiple brief episodes of care. For example, slower change is inevitable when working with non-verbal aspects of trauma, and this may be one of the reasons why treatment responses in chronic depression are superior for doses of 30 sessions or greater (Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Reynolds and Tata1999; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Schuurmans, van Oppen, Hollon and Andersson2009). With respect to the current case, consider the costs incurred by Evelyn’s treatment in the 13 years prior to receiving SR-CBT, and the potential savings in the years ahead, if her treatment gains are sustained. The efficacy of SR-CBT and its health economics are now undergoing further empirical tests.

Key practice points

-

(1) Therapists should adjust the delivery of CBT for difficult-to-treat depression, particularly when clients have not had lasting benefit from previous courses of CBT:

-

(a) When possible, increase the treatment dose compared with standard CBT.

-

(b) Pay more attention to building the working alliance by overcoming alliance barriers.

-

(c) Pay more attention to less-depressed moods as a way of finding a path out of depression.

-

(d) Conduct behavioural experiments that seek to influence clients’ preferences, rather than disconfirm their negative predictions.

-

-

(2) Therapists should consider using individualized measures, such as daily mood ratings, alongside standard measures as a way of observing trends and patterns of change.

Data availability statement

Copies of the single case dataset are available from the first author on request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues who provided feedback on drafts and contributed to the development of the treatment components: Nina Brauner, Beth Bromley, Elisabeth Felter, Dave Haggarty, Youngsuk Kim, Lucy Robinson and Karl Taylor.

Author contributions

Stephen Barton: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Peter Armstrong: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Supervision (lead); Stephen Holland: Conceptualization (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Hayley Tyson-Adams: Conceptualization (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the ethical principles and code of conduct set out by the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies and British Psychological Society. The reported study is practice-based evidence and did not receive ethical approval in advance. In lieu of this, oversight was sought from CNTW Foundation Trust management which supported service-user involvement in collecting practice-based evidence. The service user was an active participant in the research process, read the manuscript and agreed to it going forward for publication.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.