Self-help resources for depression are widely available in bookshops and via the internet. They are increasingly being recommended for use by healthcare practitioners as part of a stepped care treatment package (Reference Bower and GilbodyBower & Gilbody, 2005). Such materials provide key information and key skills to help readers tackle mild-to-moderate depression (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004). The recent review of self-help by the National Institute for Mental Health in England confirmed that it is cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) self-help that has an evidence base rather than self-help per se (Reference Lewis, Anderson and ArayaLewis et al, 2003).

Evidence for the effectiveness of CBT self-help materials varies in quality. Some reviews have been very enthusiastic in recommending the effectiveness of written CBT self-help materials (so-called bibliotherapy). Other more recent and high-quality reviews have been more measured. Although there are a number of self-help books for the treatment of depression there is little direct evidence for the effectiveness of most available books (Reference Anderson, Lewis and ArayaAnderson et al, 2005).

Books and book prescription schemes

The majority of specialists who treat patients with depression using CBT utilise written self-help materials (Reference Keeley, Williams and ShapiroKeeley et al, 2002). These are used in a variety of settings to supplement individual or group therapy, for use by those on waiting lists and within book prescription schemes in primary care. It may be that practitioner support for the use of such books is essential and to date no controlled studies of book schemes have been published.

A growing number of book prescription schemes have developed around the UK (Reference FarrandFarrand, 2005) and an example is shown in Table 1. A large range of self-help books are included on ‘recommended’ lists, which cover a range of mental health disorders.

Table 1. Self-help books for depression available on the Peninsula book prescription scheme (Reference FarrandFarrand, 2005)

| Book | Comments |

|---|---|

| The Feeling Good Handbook (Reference BurnsBurns, 1999) | American book. Long but comprehensive. Evaluated in several RCTs. |

| Overcoming Depression (Reference GilbertGilbert, 2000) | UK book. Many case examples, psychoevolutionary stance. Praised for its compassionate approach. |

| Mind Over Mood (Reference Greenberger and PadeskyGreenberger & Padesky, 1995) | American self-help manual containing worksheets and homework tasks using the traditional CBT language. |

| Overcoming Depression: A Five Areas Approach (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001) | UK self-help manual containing workbooks and worksheets. Avoids much of the traditional CBT language. Reading age 9-12 for most of the content. |

The average UK reading age has been quoted as being around 9 years (Reference AldersonAlderson, 1994), and it is clear that a proportion of patients will have problems following the content of some or all of the publications. Some books allow photocopying of either part or all of their content by professionals during their treatment of patients (e.g. Reference Greenberger and PadeskyGreenberger & Padesky, 1995; Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001).

Leaflets

Sometimes patients prefer or require information in a shorter format. Locally produced leaflets are available in many clinical units and leaflets with a wider circulation are freely available online (Table 2).

Table 2. Sources of commonly used leaflets on depression that are available online

| Source | Comment |

|---|---|

| BABCP (http://www.babcp.com) | The lead body for CBT in the UK - provides a range of free leaflets that are frequently updated. |

| Depression Alliance (http://www.depressionalliance.org/docs/what_we_offer/publications.html) | A range of free leaflets addressing depression and sex, St John's Wort, depression at Christmas, treatments, etc. |

| MIND (http://www.mind.org.uk/Information/Factsheets) | A wide range of free-to-read leaflets which can be read but not printed - also available for purchase. |

| Northumberland CBT materials (http://www.nnt.nhs.uk/mh/content.asp?PageName=selfhelp) | Excellent series of self-help leaflets addressing a wide range of issues such as overcoming anger, guilt, shame, etc., as well as low mood, etc. |

| Royal College of Psychiatrists (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/info/dep.htm) | Many leaflets addressing varying aspects of depression - e.g. depression in men, postnatal depression, etc. |

| Steps (http://www.glasgowsteps.com/help.html) | Wide range of self-help materials produced by an innovator in the area of self-help delivery. |

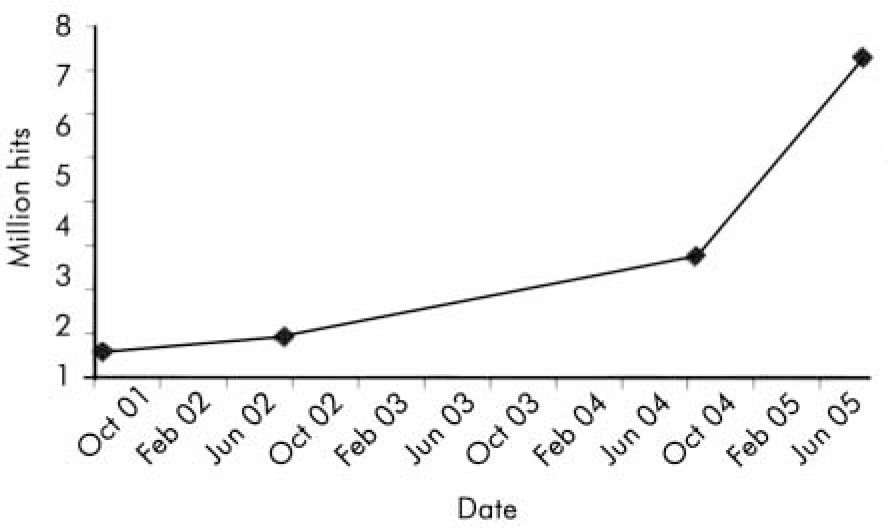

Fig. 1. Rise in ‘hits’ for SELF and HELP and DEPRESSION on Google.com

Other websites

A range of self-help websites and leaflets are increasingly available via the internet (Fig. 1).

Few studies have examined the effectiveness of psychoeducational websites in helping people with depression-however, some studies have found them to be as effective as online CBT (Reference Christensen, Griffiths and JormChristensen et al, 2004). Most sites at present provide simple information about depression. Two sites in particular offer information and life skills training for people facing low mood and depresion: Mood Gym (http://moodgym.anu.edu.au/) and Living Life to the Full (www.livinglifetothefull.com).

Conclusion

It is clear that there is an apparently insatiable desire of users and patients to obtain information about depression. This is reflected by the increasing numbers of books and websites that are available. Practitioners are also increasingly offering information leaflets and such approaches are being formalised within clinical services. Such developments may have run ahead of the evidence base and more research in practice is required.

Declaration of interest

C.W. is author of one of the Overcoming Depression and Living Life to the Full websites.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.