The discipline of political science examines pressing questions about governance, politics, and power. Our ability to generate accurate and actionable findings is enhanced by including in disciplinary discussions, institutions, and publications the voices of scholars with diverse epistemological commitments, methodological predilections, demographic traits, backgrounds, and experiences. Yet the discipline has struggled to recruit and admit to graduate programs, and retain as faculty, women and underrepresented minorities (URMs). Many individual faculty, departments, and universities have developed innovative programs and sought to create structural changes to address these gaps. The demand for such efforts is substantial and growing: as the political and social challenges facing the world multiply, responding as a discipline requires better tools and creative approaches advanced by a more diverse set of researchers.

...as the political and social challenges facing the world multiply, responding as a discipline requires better tools and creative approaches advanced by a more diverse set of researchers.

To create this heterogeneous research community, more individuals and institutions can and must begin to work immediately, in a broad range of ways, to increase our discipline’s diversity and inclusivity. There is no perfect moment, ideal starting point, or type of initiative: taking bold, creative, yet incremental steps can generate support and awaken demand even in seemingly quiescent institutional settings.

This article presents the approach taken by the Department of Government at Georgetown University: the launching of an annual week-long Political Science Predoctoral Summer Institute in 2022. The article first outlines the important challenges facing the discipline concerning the diversity of the graduate-student population. We then consider five types of programs that expand the pathways into political science. Next, we describe the Institute’s contours and structure and offer preliminary data on outcomes. The article concludes with our thoughts on steps forward, highlighting the importance of careful assessment of our efforts, departmental and university support and funding, and coordination and collaboration.

THE CHALLENGES

In 2010, women comprised only 28.6% and non-white/Euro-Americans comprised only 13.4% of full-time faculty in political science departments (American Political Science Association 2011). At least two sets of factors lead to these disparities. “Demand-side” factors include insufficient efforts by faculty, departments, and universities to recruit, train, and seek to retain underrepresented faculty (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2015; Thies and Hinojosa Reference Thies and Hinojosa2023). “Supply-side” challenges concern the narrowness and leakiness of the “pipeline” to academia for these scholars (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Lake, Shafiei and Platt2020; Cole and Arias Reference Cole and Arias2004). Much remains to be done in terms of both demand and supply. This section of the article emphasizes challenges with regard to supply.

Marginalized populations struggle at various stages of their personal and professional journey (Smole and Sinclair-Chapman Reference Smole and Sinclair-Chapman2022; Windsor, Crawford, and Breuning Reference Windsor, Crawford and Breuning2021). Although the proportion of women and URMs entering doctoral programs has been increasing over time (American Political Science Association 2021), the number of doctorates awarded to women and URMs did not increase substantially between 2000 and 2020 (National Science Foundation 2020). Women and URMs also opt out of the academic job market at higher rates after completing doctoral degrees (American Political Science Association 2019). Although we have limited aggregate data on the experiences of other underrepresented populations (e.g., people with disabilities and members of the LGBTQ community), there is ample evidence that other groups also face a host of institutional and personal challenges that warrant greater attention (Brown and Leigh Reference Brown and Leigh2018; Friedensen et al. Reference Friedensen, Horii, Kimball, Lisi, Miller, Siddiqui, Thoma, Weaver and Woodman2021; Majic and Strolovitch Reference Majic and Strolovitch2020). Various structural factors—from the founding of the discipline (McClain Reference McClain2021) to persistent disparities in hiring, recruitment, retention, self-efficacy, and professional recognition and advancement—underlie these realities (Alter et al. Reference Alter, Clipperton, Schraudenbach and Rozier2020; Claypool et al. Reference Claypool, Janssen, Kim and Mitchell2017; Kim and Grofman Reference Kim and Grofman2019; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Hardt, Meister and Kim2020).

Moreover, despite the increasing proportion of women and URMs entering doctoral programs, recent studies suggest that the path to graduate school remains difficult to traverse for students from underrepresented backgrounds and particular institutions (e.g., minority serving). Tormos-Aponte (Reference Tormos-Aponte2021) understands graduate school to be a “crucial battleground” for diversifying political science through admitting, retaining, and working to ensure the academic and professional success of underrepresented populations. URMs and women often experience isolation, discrimination, and limited access to information, sponsorship, mentorship, training opportunities, and professional recognition of their preferred research topics and methods (Almasri, Read, and Vandeweerdt Reference Almasri, Read and Vandeweerdt2022; Arnold, Crawford, and Khalifa Reference Arnold, Crawford and Khalifa2016; Key and Sumner Reference Key and Sumner2019; Kim and Grofman Reference Kim and Grofman2019; Means and Fields Reference Means and Fields2022; Mendez Garcia and Hancock Alfaro Reference Mendez Garcia and Alfaro2020; Monforti Lavariega and Michelson Reference Michelson and Monforti2020; Shames and Wise Reference Shames and Wise2017; Smith, Gillooly, and Hardt Reference Smith, Gillooly and Hardt2022; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017).

Worse, as Nadia Brown, creator of the #SistahScholar initiative, noted in an interview with Lemi, Scott, and Wong (Reference Lemi, Scott and Wong2022), challenges facing “junior women—particularly in graduate school— […] will follow them into the professoriate.” As “space invaders” who do not fit the discipline’s dominant mold, URMs have difficulty navigating norms that seem “taken for granted” by others and envisioning themselves as successful graduate students and scholars (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2015; Calarco Reference Calarco2020; Michelson and Lavariega Monforti Reference Michelson and Monforti2020). Lavariega Monforti and Michelson (Reference Monforti, Jessica and Michelson2020) noted how the lack of deep networks and interpersonal connections among URM graduate students and faculty significantly complicates “envision[ing] a future for yourself” in the academy. Sinclair-Chapman (Reference Sinclair-Chapman2019) advises graduate students and junior faculty to not “concede to the academy or the discipline’s two-mindedness about whether you belong.”

Addressing these structural barriers to joining and flourishing in the professoriate (Sinclair-Chapman Reference Sinclair-Chapman2015) requires creating better infrastructure to help URM students negotiate the transition to graduate education and ultimately to an academic career. Pipeline programs seek to build a “critical mass” of well-prepared and competitive students and to develop a community of support (Michelson and Lavariega Monforti Reference Michelson and Monforti2020, 154). Both results can contribute to counteracting the ambivalence and resistance on the part of faculty and administration with which diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts sometimes are met (Dobbin and Kalev Reference Dobbin and Kalev2016). Of course, what can be dishearteningly entrenched opposition—potentially emboldened by regressive state-level legislation (Izaguirre Reference Izaguirre2023)—ultimately can be fully overcome only through explicit institutional efforts: dedicated work at recruitment and retention within university departments and by university administration. Fortunately, initiatives aimed at achieving these goals are emerging. DEI efforts such as those discussed in the next section are a critical accompaniment to those initiatives.

POTENTIAL PATHWAYS TO INCREASING DIVERSITY

We identify five types of initiatives advanced in the discipline during the last decade to address a particular supply-side challenge: increasing diversity in the graduate-student population. Our examination identifies only a subset of the efforts that exist, which represent only a fraction of what is possible (see Reid and Curry Reference Reid and Curry2019, Sinclair-Chapman Reference Sinclair-Chapman2015, and Tormos-Aponte Reference Tormos-Aponte2021 for other overviews). To identify these initiatives, we drew on published scholarship describing specific solutions that have been actively introduced in one or more contexts.

One type of initiative involves inclusive pedagogy and/or presenting ideas related to DEI through various learning opportunities, such as gender mainstreaming in syllabi (Atchison Reference Atchison2016) and an annual “Gender Day,” which aims to develop gender analytic skills (Macaulay Reference Macaulay2016). Barham and Wood (Reference Barham and Wood2022) teach graduate students the “hidden curriculum”—that is, “…informal norms and rules, expectations, and skills that inform our ‘ways of doing’ academic practice (Calarco Reference Calarco2020).”

A second set of efforts engages undergraduate students as researchers and/or publishing partners. Becker, Graham, and Zvobgo (Reference Becker, Benjamin and Zvobgo2021) use a Mentored Undergraduate Research Experience/Stewardship model to “recruit, train, mentor, support a diverse new generation of social scientists.” Acai, Mercer-Mapstone, and Guitman (Reference Acai, Mercer-Mapstone and Guitman2019) “…engag[e] students as partners…”—in publishing in particular—“to improv[e] gender equity by fostering agency and leadership for women.” Dickinson, Jackson, and Williams (Reference Dickinson, Jackson and Williams2020) use a multidimensional strategy that exposes beginning undergraduates to research, mentorship, and resources.

Third, programs aimed at broadening the PhD pipeline are invaluable for diversifying graduate education. The American Political Science Association (APSA) Ralph Bunche Summer Institute aims to “introduce undergraduate students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups” to political science doctoral education. Adida et al. (Reference Adida, Lake, Shafiei and Platt2020) developed a seven-week pipeline program for students from two Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Tormos-Aponte and Velez-Serrano (Reference Tormos-Aponte and Velez-Serrano2020) created the Minority Graduate Placement Program (MIGAP) to support undergraduate students from Puerto Rico in doctoral studies.

In a fourth type of initiative, faculty focus on mentoring and sponsoring graduate students. Barnes (Reference Barnes2018) works actively to get and keep female students interested in research methods, for instance, through networking. Fattore and Fisher (Reference Fattore and Fisher2022) use a “pedagogies of care approach” (Motta and Bennett Reference Motta and Bennett2018) to mitigate “the harm the current [mentoring] system has on PhD students and early-career faculty who do not fit the ideal worker image.” Others adopt “sponsorship”—that is, “spending one’s social capital or using one’s influence to advocate for a protege” to advance women of color in the discipline (Means and Fields Reference Means and Fields2022).

The fifth type of effort emphasizes creating spaces and community for URM students—for example, Women Also Know Stuff (Beaulieu et al. Reference Beaulieu, Boydstun, Brown, Dionne, Gillespie, Klar, Krupnikov, Michelson, Searles and Wolbrecht2017); Sistah Scholar; People of Color Also Know Stuff; Women of Color Workshops; the “junior women of color collective” (Lemi, Scott, and Wong Reference Lemi, Scott and Wong2022); the Visions in Methodology program (Barnes and Beaulieu Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2017); graduate writing groups (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018); and women of color mini-conferences, diversity caucuses within disciplinary associations, and workshop retreat spaces (Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2015; Sediqe and Nelson Reference Sediqe and Nelson2022).

Thus, although there is still much more to do, efforts to enhance the diversity of the discipline’s graduate-student population accelerated during the last decade. We learned from and built on these initiatives to develop a new element of the diversity infrastructure at Georgetown University.

GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY’S INAUGURAL POLITICAL SCIENCE PREDOCTORAL SUMMER INSTITUTE

The idea of creating a Political Science Predoctoral Summer Institute (https://government.georgetown.edu/ps-psi/#, hereafter “the Institute”) at Georgetown University arose from broader discussions among faculty and graduate students in the Department of Government about how to make our community—and our graduate-student population in particular—more diverse and inclusive. Our efforts proceeded incrementally: we increasingly recruited doctoral students at targeted events, offered application-fee waivers, and ceased to require Graduate Record Examination scores as part of graduate applications. We learned more by preparing a comprehensive bibliography of related literature and attending relevant panels at the 2018 and 2019 APSA Annual Meetings. Following the “critical juncture” that the racial-justice protests after the murder of George Floyd in 2020 represented (Collier et al. Reference Collier, Munck, Tarrow, Roberts, Kaufman, Taylor, Scully, Dominguez, Mazzuca, Gould and Dunning2021; Paulson-Smith and Tripp Reference Paulson-Smith and Tripp2021), efforts aimed at DEI gained new urgency and momentum in our department: students and faculty alike began to call more openly for meaningful action.

The important groundwork that had been laid, complemented by a generous gift from an anonymous donor, facilitated the development of the Institute. We began by assessing existing efforts at our home institution, which enabled us to evaluate its unique needs and strengths. We also surveyed other pipeline programs in political science and adjacent disciplines at other US institutions. Whenever possible, we interviewed the leaders of these programs to better understand the programs’ goals and structure as well as the challenges leaders faced.

These activities led us to clarify the goals of the Institute. We determined that it would have two overarching practical objectives: (1) to demystify the process of applying to graduate programs and obtaining a doctorate and to help students prepare to do so; and (2) to equip students to make an informed choice about pursuing a graduate degree and begin to see a place for themselves and their work in graduate school and beyond. Similarly, we decided that our Institute would provide a realistic picture of the prospect of landing a faculty position in political science and enthusiastically discuss multiple career paths that political science PhDs can pursue. We resolved to consider some participants discovering that they did not wish to pursue doctoral education or a career in the academy as a positive outcome.

In view of the research we had done, our goals, and funding and faculty availability, we decided that a five-day “skills deep dive” was the optimal structure for our program. Our Institute, then, was not modeled after immersive multiweek summer programs that seek to introduce students to the intellectual demands of graduate coursework and research (see Adida et al. Reference Adida, Lake, Shafiei and Platt2020, Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2017, and Tormos-Aponte and Velez-Serrano Reference Tormos-Aponte and Velez-Serrano2020 for examples). Rather, we modeled the Institute on seminar-based programs with a typical length of two to four days because our goal was to elucidate graduate education and academia for URMs (i.e., bolster the pipeline into the profession). Specifically, we decided to offer an early-summer, full-time residential program for 20 rising juniors and seniors who are interested in pursuing a PhD in political science and who are currently attending college in Washington, DC, and four neighboring states.

Specifically, we decided to offer an early-summer, full-time residential program for 20 rising juniors and seniors who are interested in pursuing a PhD in political science and who are currently attending college in Washington, DC, and four neighboring states.

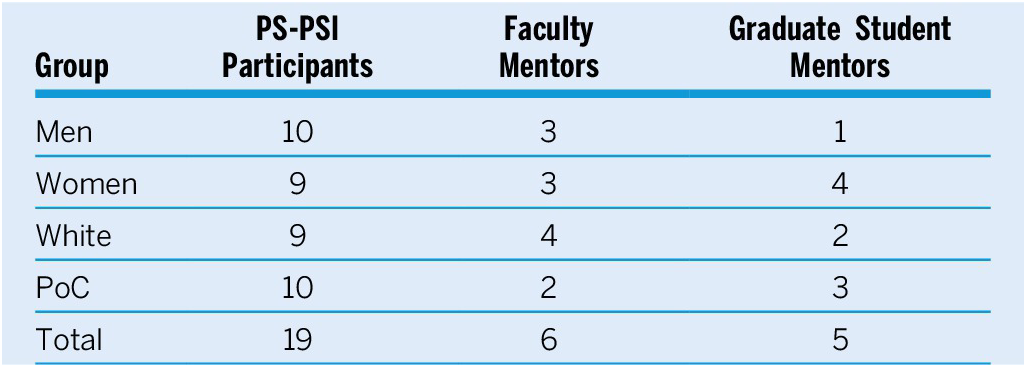

Our recruitment efforts included contacting directors of undergraduate study in political science (or similar) departments at colleges and universities in those states, and reaching out to faculty within our individual networks. The 2022 cohort included various underrepresented groups, such as nontraditional undergraduates, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ-identified students. Fifty two percent of participants identified as people of color and 47% identified as women (table 1). Of these participants, 84% had political science or a related field as at least one of their majors and 73% attended public universities (Mitra et al. Reference Mitra, Kapiszewski, Kleinpaste and Smith2023).

Table 1 Participant and Mentor Demographics

We designed the Institute’s curriculum to introduce the goals, substance, and methods of political science; clarify what applying to graduate school entails; discuss the experience of being a graduate student and political scientist; and consider the careers that political science PhDs can pursue. Guest speakers included university leadership, faculty and staff from ours and affiliated departments and units, and visitors from nearby universities and APSA’s headquarters. Five doctoral students in our department served as “PhD Ambassadors” by contributing to designing and managing the Institute and serving as mentors to participants. Given our department’s limited experience in DEI efforts, we were heartened by our colleagues’ support for the Institute and their willingness to participate during the summer.

Although the Institute was not focused on participants designing and conducting a research project, a key objective was to empower them to envision themselves as researchers. Applicants submitted a brief “research pitch” as part of their application, and those who were selected to attended the Institute were provided guidance in multiple learning formats on how to convert that “pitch” into a longer “research proposal” in advance of the Institute. During the Institute, participants presented their research proposal in “step-back consultation” groups (Deats Reference Deats2021). In this innovative presentation format, group members take on and discuss work presented as if it were their own. The presenter initially “steps back” and listens and then is invited to answer the group’s questions and ask their own.

Mentoring was a critical part of the Institute. Each student was assigned one PhD Ambassador as a student mentor and one faculty mentor. Whenever possible, we matched students and mentors by substantive research interests. Each mentor met individually with their mentees through the week to explore mentees’ research topic more deeply and to answer questions about graduate school. These mentorship relationships are expected to continue for at least one year as participants apply to graduate school (if they so choose) and/or continue to develop their research topic. Table 1 provides demographic information about mentors: more than one third were men, a positive parameter because male engagement in these efforts, particularly in mentoring, is critical to changing academic culture (Windsor and Thies Reference Windsor and Thies2021).

To evaluate the Institute and its outcomes, we conducted pre-Institute and post-Institute surveys with student participants, PhD Ambassadors, and participating faculty. Figure 1 summarizes results from the post-Institute student participant survey (N=11). Respondents reported that the panels and roundtables (100% of respondents), conversations with the PhD mentors (100%), and presentations and opportunities for receiving feedback on their research (90%) were the most helpful aspects of the program. Conversations with faculty members (72%) and other participants (72%), as well as discussions of nonacademic career trajectories, also were helpful. Students indicated that the step-back consultations helped them with their research, demonstrated how to provide feedback to others, and showcased the diversity of topics and methods in the discipline. At the conclusion of the Institute, one student stated, “I feel like my research ideas were really heard during this Institute for the first time.”

Figure 1 Student Participant Evaluation of PS–PSI Program

Comparing the results from our pre-Institute (N=19) and post-Institute (N=11) surveys of student participants suggests that the Institute helped participants in various ways. The number of participants who rated themselves likely or very likely to apply to a PhD program in political science or a closely related field remained relatively stable (i.e., nine and seven students in the pre-Institute and post-Institute surveys, respectively). However, respondents reported knowing much more about political science doctoral programs, the application process, and available resources for potential applicants after the Institute (figure 2). For instance, only six of the students who completed the pre-Institute survey expressed familiarity with political science subfields, whereas 11 expressed familiarity in the post-Institute survey. Likewise, only two respondents indicated that they were familiar with research methods before the Institute, whereas nine respondents indicated familiarity afterwards. Survey results also suggested that the Institute helped students to better understand the structure and content of PhD programs; skills developed during a PhD; how to secure funding for a PhD; and faculty advising, networking, and publishing. In the post-Institute survey, respondents unanimously indicated that they felt prepared or very prepared to apply to a PhD program in political science or a closely related field; 10 respondents stated that the Institute contributed or contributed significantly to their preparedness.

Figure 2 Number of Student Participants Familiar with PhD Applications and Programs

Some of the feedback participants offered in the post-Institute survey mirrored our own reflections. We continue to consider how to balance discussions of core topics such as the fields and methods of political science, subtle yet potent dynamics such as the structures and hierarchies of power in the academy and the discipline, and presentation and critique of participants’ research. In the post-Institute survey, some participants called for more attention to academic hierarchies, mental health, and work–life balance in graduate school and academia as well as to the development of their research. Like the organizers, participants hoped for more diverse panels and roundtables, including more political scientists undertaking civically engaged research and, as one comment stated, “more ‘nontraditional’ scholars working on, e.g., environmental justice or decolonization issues…[or] doing advocacy work or supporting marginalized communities….”

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

This article discusses core challenges related to DEI in the discipline of political science and reviews initiatives that have been advanced during the last decade to address the lack of diversity in the graduate-student population. We describe the elements, strengths, and limitations of the Political Science Predoctoral Summer Institute developed by the Department of Government at Georgetown University. Just as we were inspired by the innovations and efforts of other scholars, we hope our recounting of and reflection on our journey may stimulate others to take action. We conclude by offering three ideas for moving forward together.

First, it is important for those who are developing DEI programs to be clear about what “success” looks like and to create systematic strategies for evaluating program execution and outcomes. Predetermining what will be considered successful outcomes can be challenging given the relative newness of such initiatives and ongoing discussions of what constitutes equity in the academy. Nonetheless, assessment is crucial: generating empirical evidence of the advantages and disadvantages of different types of programs over time will enable their explicit comparison. Such analysis will bolster funding proposals—which are particularly important for programs introduced at institutions with a limited budget and where donor support is rare—and inform subsequent efforts.

Second, institutional backing is critical. Departments must advocate for DEI efforts, creating committees and infrastructure to support them. In turn, universities must develop and demonstrate a commitment to such initiatives, supporting change-making departments. Backing from disciplinary associations—with APSA in a leading role—is crucial, as is the provision of funding. Private and public funders should earmark resources for such initiatives and aggressively promote these opportunities and their expansion in the humanities and social sciences, as organizations such as the National Science Foundation have done in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

Third, communication and coordination—both within and across universities and other entities—are decisive for the success of DEI efforts individually and in aggregate. The heterogeneity of ongoing efforts in the discipline is a great strength: each type of program addresses different aspects of the discipline’s diversity challenges, and together they can begin to “level the playing field.” Those who are advancing DEI initiatives must share plans, lessons, and insights to learn from one another’s challenges and successes and to identify synergies among their efforts. Knowledge sharing, collaboration, and coordination across departments and universities will allow us to scale up these efforts to make use of scarce resources. That the discipline has arrived at a juncture at which there are sufficient initiatives to require coordination is both a development to celebrate and an opportunity to grasp.

...communication and coordination—both within and across universities and other entities—are decisive for the success of DEI efforts individually and in aggregate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Department of Government at Georgetown University for supporting our efforts to create the Political Science Predoctoral Summer Institute, an anonymous donor, various Georgetown University units; and the American Political Science Association for generous funding for the Institute; and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on this article. We also acknowledge and thank the student participants in the first annual Institute: Alexander Allen, Miles Barton, Bo Belotti, Steven Berit, Adarra Blount, Ryan Bookstein, Rachel Delgado, Justin Fox, Leo Hojnowski, Marzia Hussaini, Kassidy Jacobs, Sharon Jeon, Rafael Jorge, Jessica Martin, Kawika Ke Koa Pegram, Alyson Reynolds, Ross Richter, Kabita Sen, and Roseanna Yeganeh-Kazemi.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QKCICV.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.