In an old wooden card catalog that no longer stands in Argentina’s National Archive, under the entry titled “negros,” there was, for many years, an index card for someone called “El negro Raúl,” or Black Raúl. I happened upon that card, and the collection of photographs to which it pointed, in 2010 while searching for sources for a twentieth-century history of Argentina’s African-descended population.

I had not expected to find much. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, people of African descent made up a substantial portion of the population of the territory that would become Argentina: more than 30 percent of the inhabitants of Buenos Aires, the city of my birth, and over 50 percent of some provinces to its northwest. But over the course of the twentieth century, most Argentines came to believe that our nation no longer had a Black population. At the dawn of the twentieth century (so the story goes), the last descendants of Argentina’s enslaved Africans had succumbed to the combined effects of warfare, disease, and intermixture with White immigrants, “disappearing” from what became a thoroughly White citizenry.1 Afro-Argentines became casualties of a black legend, much like Native peoples in the Black Legend of Spanish colonization of the Americas: a narrative that, in its attempt to highlight European agency or cruelty, also exaggerated the annihilation and produced the invisibility of an entire ethnic group.2

Argentines of African descent did not, in fact, disappear in the twentieth century. But by and large, they ceased to be recognized or to self-identify as such. Since the 1980s, activists and scholars have worked assiduously to debunk the myth of disappearance, arguing for recognition of Afrodescendants’ historical importance and continuous presence on Argentine soil. But the black legend of Afro-Argentine annihilation adapts and persists. For most Argentines, including many archivists and librarians, the Afro-Argentine presence remains confined to the nation’s deep past, when it is recognized at all. So I was not surprised, that day at the archive, to see that the few cards behind the subject divider “negros” referred mostly to people racialized as Black who lived and died prior to the twentieth century.

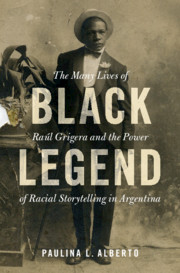

Yet “el negro Raúl,” the Black man whose image developed before me across eleven striking photographs, was clearly a twentieth-century figure. In one arresting studio photograph taken in his youth, he poses in black coattails and silk waistcoat, a walking cane in one hand and a luminous white magnolia on his lapel. In other images, an older incarnation of the same man, cocooned in ragged overcoats, walks the city streets shadowed by the police or shelters uneasily in doorways. In another series, an even older “negro Raúl,” his legs bowed by age but his face beaming for the camera, strolls near the entryway to some sort of institutional building, assisted by men in white coats. I could see from the pencil markings and the snippets of newspaper articles pasted on the backs of the photographs that his full name was Raúl Grigera and that he had been famous – so famous that photographers and journalists sought him out over many decades to tell his story. But who was “el negro Raúl”? And what had made him famous?

I pulled the thin threads of information dangling from these photos, and hundreds of stories came tumbling forth. Thanks to traditional historical sleuthing and the marvel of text-searchable books and periodicals, I was able to collect more than 280 published textual and visual sources on “el negro Raúl,” as well as several more unpublished photographs. This corpus spans more than a century: from Raúl’s first print appearance in 1912, interleaved among coverage of the sinking Titanic, to 2011, when the local press mentioned him in relation to the United Nations’ declaration of the “International Year for People of African Descent,” and beyond. It comprises genres from across elite and popular culture – newspaper and magazine articles, plays, poems, songs, comic art, photographs, portraiture, films, novels, essays, histories, memoirs, city and neighborhood chronicles, and blog posts. Its creators were mostly Porteños (residents of Buenos Aires) from a variety of social backgrounds, political persuasions, and degrees of renown in the city’s intellectual and creative circles. Almost all these chroniclers of “el negro Raúl” were men, and except for one African American traveler, all were people considered White by Argentine racial norms.

Yet it quickly became apparent that this profusion of sources offered no straightforward answer to the questions of who “el negro Raúl” was and what made him famous. What I had before me were suspiciously repetitive stories about a semi-fictional character that referred more to each other than to the life of a historical individual. Authors rarely offered citations for their accounts, breezily invoking hearsay, oral tradition, or common knowledge instead; when they did, the account cited was equally unfounded or in turn referred to yet another baseless story. Plagiarism abounded. Articles in the popular press “refried” earlier accounts (to cite local journalists’ lingo), but never so thoroughly that words, phrases, and tropes could not easily be picked out whole. Photographs, drawings, and cartoons told similarly standardized stories visually. This uniformity was especially palpable in retrospective accounts from his final decades (1930s–50s) or after his death (1955), the vast majority of my sources.3 Evidently, the people who wielded the power to narrate Raúl’s life had reduced it to what novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls a “single story” – an impoverished, incomplete, dangerous account that “show[s] people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again,” until that becomes “the definitive story of that person.”4

More troubling still, the single story of Raúl’s life reiterated Argentina’s dominant narratives of race. Especially in retrospective or posthumous accounts, the patterned tale of his (nebulous) origins, (bizarre) rise to fame, and (inevitable, spectacular) decline and death plotted exactly onto the black legend of Afro-Argentine disappearance in circulation at least since the mid-1800s: that Argentine negros were rarities, fundamentally out of place, and well on the path to extinction. There was nothing subtle about it: the stories about “el negro Raúl” were parables – projections of one story onto another – about the inexorable demise of the Afro-Argentine population.5

If we were to believe these formulaic tales, Raúl’s story would look something like this:

His origins were unknowable. He came out of nowhere, his presence in twentieth-century Argentina was inexplicable. Perhaps he was an orphan, or the only son of an agonizing and ancient father, or of a father who died young and left him to face life alone. Or perhaps he spontaneously materialized, falling from the sky or emerging from a hole in the ground. “It never was possible to find out where he had come from,” one midcentury writer sighed, summarizing the impossible task of exposition.6 Behind “el negro Raúl” there was no lineage, no continuously existing Black community. The trope of his unfathomable origins expelled Afro-Argentines from national history and from historical recoverability.

Raúl’s swift ascent to spectacular fame – the rising action and climax of these tales – generated far more speculation than his nebulous origins. All accounts agree: “el negro Raúl” was famous in the 1910s and 1920s as the Black buffoon of the niños bien, the notoriously spoiled, carousing young men of the White Porteño elite. In exchange for their cast-off finery, lavish food and drink, and inclusion in their nocturnal debauchery, Raúl made himself the niños’ plaything: the willing object of sadistic practical jokes that risked dignity, life, and limb. His whole persona was a sham: the luxurious outfits on which he prided himself, in which he ostentatiously posed for the camera or paraded himself about town, were secondhand, ill-fitting, out of season. “El negro Raúl” may have fancied himself a refined dandy, but he was no more than a self-deluded clown who mistook attention for affection. And why did he subject himself to such treatment at the hands of aristocratic idlers? Authors picked from a smorgasbord of anti-Black racial stereotypes common throughout the Americas. He was inherently servile or driven to ape his “betters”; he was mentally insufficient or deranged or insane, or struggled with a deep inferiority complex; he was a lazy vagrant who hated work and debased himself to secure the easy life; he was deviant and tricked others to get by. By all accounts, “el negro Raúl” was a throwback in the modern White nation, evolutionarily out of place, unable to play fairly by the rules of democracy and capitalism.

Then came the stories’ extended dénouement: Raúl’s much-anticipated decline and death. Years of easy living had taken their toll, and as Raúl’s aristocratic protectors suffered through the stock market crash of 1929, they abandoned him. He became a pitiful sight, reduced to begging and wearing rags, revisiting his earlier haunts in the vain hope of handouts and sympathy. Speculations about madness became certainties once news began to circulate that Raúl was dying in a rural mental health institution. And dying, in these stories, was a protracted, iterative affair. As early as the 1930s, contemporaries declared “el negro Raúl” to be in the twilight of his life, and in the 1940s and 1950s, mistaken assertions of his death were so frequent that they became part of the story surrounding him. He was, writers joked, a dead man who kept returning to life, forcing newspapers to retract their repeated obituaries until his real death in 1955. Prominent Argentines had vigorously repeated premature assertions of Afro-Argentine decline and death since the nineteenth century; storytellers in the mid-twentieth century simply conscripted Raúl into that broader narrative. His premature death was permanently useful to tell and retell as part of a tragicomedy about the foolishness of persisting in being a Black person in a country that had outgrown them (or in its great wisdom, had arranged never to have any).

*

When I first discovered these tales about “el negro Raúl,” I thought they might make for an illuminating window onto the relatively unexplored topic of racial ideologies in twentieth-century Argentina. The character they constructed, his far-reaching “narrative resonance” with Porteño audiences, offered an unusually potent lens through which to examine ideas about Whiteness and Blackness over time and across social class, political ideologies, and literary genres.7 But I quickly lost all heart for a project centered on these stories, with their gruesome deformation and muzzling of the protagonist, their perpetual restaging of his humiliation and death. As literary critic and historian Saidiya Hartman writes about the countless girls and women behind the abused figure of Venus in the archive of Atlantic slavery, “[t]he stories that exist are not about them, but rather about the violence, excess, mendacity, and reason that seized hold of their lives, transformed them into commodities and corpses, and identified them with names tossed-off as insults and crass jokes.”8 To be sure, exhuming and dissecting these sadistic tales helps expose what Hartman calls the “scandal of the archive,” or in my case, the violence of Argentine racial ideologies codified in stories.9 The twentieth-century tales about “el negro Raúl” lay bare, with painful clarity, the raw racism and White supremacy so often ignored or dismissed by Argentines. But by taking only those stories as my subject, I, as yet another White Argentine narrator of Raúl’s life, would simply have amplified their power, conceding to the character storytellers had constructed and to their conceit (in the end, a provocation) that it was “impossible” to know anything outside its bounds.

I chose not to use “el negro Raúl” as a lens through which to peer at something else. I decided instead to try to reconstruct Raúl Grigera’s life as lived in dialogue both with stories about his character and larger narratives of Blackness and Whiteness in Argentina. When friends and colleagues warned me that trying to find a “historic” Raúl Grigera embedded in family and community was a quixotic undertaking, they did so not unkindly or unreasonably. From the mid-1800s onward, the Argentine state largely suppressed racial labeling in the name of liberal racelessness, and many Afro-Argentines themselves ceased identifying with racial labels (especially the hated negro). This made Afrodescendants invisible in national censuses and many other official sources. In turn, the supposed nonexistence or irrelevance of Afrodescendants to Argentine culture rendered their African descent invisible in archival and bibliographic collections, catalogs, or finding aids. But working backward from an individual of known African ancestry who lived well into the twentieth century opened up new possibilities for identifying other Afrodescendants in the past, whether or not they were marked as such in historical records. On another floor of the same archive that housed the photographs of “el negro Raúl,” scores of documents about Raúl Grigera’s family’s history – notarial, judicial, and property records on his ancestors, enslaved and free, reaching back to the early 1800s – awaited anyone with the interest and patience to find them. These sources in turn led me to other historical archives, as well as to the rather less accessible repositories of functioning mental, correctional, juridical, and police institutions, which held unimaginably rich information about Raúl and many of his Afro-Argentine relatives, friends, and neighbors.

As the corpus of derisive stories about “el negro Raúl” receded in size and significance before this mounting archive of the lives of five generations of Afro-Argentine men and women, the scope of my project shifted again. The life stories of Raúl’s ancestors did not just disprove the narrative of Afro-Argentine disappearance but raised new questions. How did Afro-Argentines experience their own supposed erasure? And while powerful White Argentines were busy narrating Afro-Argentines’ disappearance, what other stories were Afro-Argentine men and women telling and living? Similarly, the information I uncovered about Raúl’s life did not just disprove the sordid stories later told about him; it too raised new questions. What was the relationship between his life and the stories told about it? What was it like, for Raúl, to be not only a Black man in twentieth-century Argentina, but a Black celebrity? I saw that the stories about “el negro Raúl,” and the broader narratives of race they echoed and mobilized, were just one piece of a larger history of the relationship between ideologies of race and lived experiences of Blackness in modern Argentina. This multigenerational history of Argentine Blackness and of Black Argentina, with Raúl Grigera at its center, was the one worth telling.

*

Readers might notice that I use story to refer to the tales about “el negro Raúl” and narrative to refer to broader ideologies of race. Although both terms, broadly speaking, denote a relation of events, I find it useful to distinguish between story as an “event unit” (a relation of who, what, when, where, and why), and narrative as “a system of stories” related to one another through coherent themes. When narratives sediment and endure over time, they become “master narratives.”10 Narratives may be the more resilient, but stories do the everyday work to prop them up. In Argentina’s case, stories about “el negro Raúl” fleshed out otherwise abstract, dry, or featureless racial narratives about disappearing Blackness and triumphant Whiteness with a lifelike character, familiar settings, gripping plots, colorful vocabularies, and compelling morals. Porteños young and old who might never hear the dreary declamations of national and foreign racialist thinkers could exchange anecdotes, chuckle at cartoons, watch a play, or hear a song about the misadventures of “el negro Raúl” and absorb many of the same lessons.

The hundreds of stories about “el negro Raúl” are what I call “racial stories”: accounts that mobilize the uniquely persuasive powers of storytelling to breathe life into racial ideologies, disseminating, naturalizing, and reinforcing them at the capillary levels of public discourse.11 Recent scholarship across literary studies, psychology, neurocognition, philosophy, sociology, legal studies, and critical race theory shows that stories (and narratives) are uniquely effective at promoting empathy and changing attitudes toward stigmatized groups by immersing readers in simulated experiences, exposing them to anti-stereotypical situations and characters, and encouraging perspective-taking. Yet these same powers to transport and absorb, to render a worldview inevitable or natural, make stories that reinforce racist and other exclusionary sentiments extremely difficult to dispel.12 As critical race theorist Imani Perry argues, unlike flat stereotypes or schemas, “racial narratives not only give you a particular image; they tell you something consequential that will follow in the lives of people or characters in ways that are presumably reflective of their membership in a particular racial group.” Racial narratives presume outcomes, and through repetition and persuasion they often bring about the very prophecies they foretell. Because they so effectively “teach us to engage in practices of racial inequality” and to make “decisions about how to treat individual members” of racialized groups, racial narratives drive discrimination, dehumanization, and even violence against people marked as racially Other.13

The case of “el negro Raúl” offers an astonishing and harrowing illustration of the power of stories to make and disseminate ideas about race, to create unequal and unjust collective outcomes, and to circumscribe or ruin individual lives. We have seen how hundreds of Porteños who reflected back on Raúl’s life from the middle decades of the twentieth century recounted his story, and to what ends. This book harnesses the power of storytelling to tell a critical counter-narrative. It is a story of a man, Raúl Grigera, who fashioned himself into an alluring character, “el negro Raúl,” only to have authorship usurped by storytellers who, in deforming the character, unmade the man.

In the 1910s and 1920s, Raúl Grigera was an audacious Black dandy, an eccentric bohemian icon, a man who called himself “el murciélago” (the bat) – a mysterious creature of the night. Using the freedoms granted to men, he moved seamlessly among the city’s after-hours hotspots, seedy and glamorous alike: the illegal gambling dens of his working-class neighborhood, knife fights outside disreputable bars and cabarets, the foyers and plush seats of downtown theaters, and the city’s crowded dance floors, where he led revelers in tango and other African-inflected rhythms. Using his charms, physical grace, and sartorial flair, Raúl made himself the subject of scores of newspaper and magazine stories, poems, plays, and tangos. He posed for photographs, became the protagonist of the first Argentine comic strip, and made cameo appearances in early silent films. As the stories multiplied, “el negro Raúl” became a rare Afro-Argentine celebrity: a Black legend.

This fame was never free of the racism that abounded in Argentine society. But as sociopolitical upheavals expanded the meanings and threats of Blackness (slowly after 1916, precipitously after 1930), Raúl fell prey to racial narratives that cast him as an aberration in the White nation: an uppity Black man who dared too much and flew too high, and was doomed to fall into misery, despair, and oblivion. Storytellers began to recast his fame as infamy, to predict his fall, and to declare him dead before his time. And life followed art: the defamatory racial stories about the character “el negro Raúl” narrowed the kinds of personas Raúl Grigera could assume or project in the city’s nightlife, stripping him of authorship and channeling his life trajectory toward the very few unsavory dénouements imagined for him. As his character’s star fell in the public imagination, in the 1930s Raúl himself began a long decline into destitution and panhandling, periodic homelessness, repeated police detention, illness, and hospitalization. In 1942, he was confined to the mental institution in which he died in 1955. After his death, the tales about him continued unabated for decades. His fall made for an even better story than his rise to fame.

Stories were central to Raúl’s fate as an extraordinary Afro-Argentine demoted from Black legend in his own right to lead protagonist in the black legend of Afro-Argentine demise. Stories are central, too, to my own counter-narrative – not just as objects of critical analysis, but as a method for disentangling the man from the caricature. Only another story (or better, many), attentive to the destructive power of racial storytelling but committed to its equally potent capacity to “shift the narrative,” can displace the defamatory ones that still exist.14

*

The book that follows therefore tells a story – or rather, three entangled and overlapping ones. The first is a microhistory or deeply contextualized biography of Raúl Grigera and his family over several generations, spanning the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The second is a social, political, and cultural history of the racial stories about his character, “el negro Raúl,” from the early twentieth century to the present. The third is an intellectual history, cutting across all three centuries, of the broader racial narratives that shaped the lives of Raúl, his family, and his community – the same racial narratives that fed, and fed upon, the racial stories about Raúl. The setting is always the port city of Buenos Aires, which enters our story as the seat of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata and becomes, after the late nineteenth century, the capital of a unified Argentine Republic. The story this book tells is thus, strictly speaking, a Porteño one, distinct from many other possible stories about Afrodescendants across the national territory.15 But because of the city’s overwhelming weight in Argentina’s political, cultural, and intellectual life – its ongoing draw for internal migrants, many of them Afrodescendant, and its writers’ and thinkers’ efforts to make Buenos Aires stand for the nation as a whole – this Porteño story is deeply enmeshed with a national history.16 This Porteño story is also, like the port city itself, marked by long-standing exchanges of people, ideas, and culture across the greater Río de la Plata region, especially Uruguay and Brazil.17

To tell this layered social, cultural, and intellectual history, Black Legend experiments with narrative style. Inspired by the techniques of microhistory, experimental narrative history, and judiciously speculative histories about people marginalized or silenced by Western or postcolonial archives (often pioneered by women of color historians), I use my historically informed imagination to “get the documents to speak” as volubly as possible about the lives of the people who made them and about whom they were made.18 Similarly, I present my readings of these documents – their content, form, silences, materiality, and their circumstances of production, archiving, and retrieval – in a storytelling mode in which I as a historian am sometimes a character.19 I signal my informed intuitions with questions, the subjunctive tense, the “maybes” and “perhapses” of more standard histories, and the perspective-shifting familiar to narrative historians, while endnotes offer further detail on my processes of historical reconstruction. Because I envision “racial storytelling” not just as my subject and analytic, but also as a method for combining social, cultural, and intellectual history about race, I use storytelling to dramatize and embody otherwise abstract processes or theoretical arguments. In particular, the nested definition of story and narrative explained earlier helps bring to life the distinct but intertwined dynamics I examine in this book: how Afro-Argentines experienced, contested, and reshaped narratives of disappearing Blackness and master narratives of Whiteness through the everyday mediation of racial stories about specific characters, people, or “types,” including – but not limited to – the stories told relentlessly about “el negro Raúl.”

To show how those three layers – individual histories, racial stories about specific characters, and master narratives of race – interweave and intersect, I also experiment with narrative structure. Chapters move chronologically forward from the mid-1800s to the present, reconstructing individual lives, the racial stories that elite Argentines told about specific Black people, and master narratives of Blackness and Whiteness in each period, setting these registers into dynamic and interactive motion. At the same time, the book works retrospectively, framing each chapter with episodes from the life of “el negro Raúl” as told by his defamatory storytellers (origins, rise to fame, decline and death, posthumous memory). Each chapter locates the deep roots of these fanciful stories in long-standing racial narratives, and exposes the gaps (as well as the unexpected connections) between racial stories or narratives and the historical record. Raúl’s life span (1886–1955) is the fulcrum of my story’s overlapping time frames. But the book opens with Raúl’s grandparents’ generation in the mid-1850s, when narratives of Black disappearance first took shape. And it ends in the present, when the stories about “el negro Raúl” that first arose in the early 1900s, as master narratives of Whiteness were crystallizing, coexist tensely with a resurgent Afrodescendant movement and efforts at “revisibilization.”

A few key themes recur throughout Black Legend, two of them encapsulated in the title itself. The first: the black legend of Afro-Argentine disappearance and its implications for telling a continuous history of Afro-Argentina from the nineteenth century to the present. With the exception of the small but energetic group of scholars specializing in that subfield, Argentine histories are largely silent on the subject of Afro-Argentines.20 Even among specialists, histories of Afro-Argentines that begin in the colonial period or nineteenth century almost never make it past the threshold of the twentieth century because of the very real difficulties of writing about Afrodescendants once they no longer self-identified or were officially recognized as such.21 Yet today, in the early twenty-first century, Argentina has a diverse Afrodescendant community and small but dynamic activist movements. Thanks to them, and to the knowledge they have produced in collaboration with mostly White historians, anthropologists, or sociologists,22 we know that Afro-Argentines did not so much “disappear” in the twentieth century as become forcibly or willingly invisible. This “invisibilization” took place through a combination of storytelling (in history, literature, art, and many other fields) that relegated Afrodescendants to the deep past, shifting racial identifications that silenced or minimized Blackness, aggressive state-driven policies of assimilation, and widespread interpretations of racial mixture as resulting in Whiteness. Yet the missing twentieth century in histories of Afro-Argentina – the largely uncharted period between Afro-Argentines’ supposed disappearance and their recent institutional reemergence – makes it difficult to know how individuals of African descent experienced the process of becoming “invisible.”

Because Raúl Grigera became a Black celebrity and a lasting touchstone for public discussions of Blackness just as Black people were declared to have vanished, his life and narrative afterlives provide a rare opportunity to understand and to relate, in vivid detail, how a person openly identified as negro experienced and contributed to the transformations in racial ideologies and categories that made Afro-Argentines invisible in the twentieth century. Raúl’s story, moreover, makes visible the stories of many other Afro-Argentines hitherto unknown. By following the trajectories of Raúl, his enslaved and free ancestors, and other people of African descent across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Black Legend throws into question Argentina’s myths of Whiteness, official racelessness, and Black disappearance. At the same time, as a White settler society in which (in contrast to the United States, for example) any White ancestry combined with the right behaviors could attenuate or even erase a person’s Blackness, Argentina productively confounds what readers might imagine “Black” and “White” to mean.

Black celebrity is the second recurring theme encapsulated in the book’s title. Despite their overall lack of charity, not one of the storytellers who later recounted the life of “el negro Raúl” doubted that he was a living legend. So famous was he that some of the most exalted names in Argentine literature used “el negro Raúl” as a measure or example of the encumbrances, fickleness, and vagaries of fame itself. Jorge Luis Borges, in a recorded interview with Manuel Mujica Láinez, joked that “we are the heirs of el negro Raúl”: public figures shackled by their own reputations, obliged to return the greetings of countless unknown admirers and passersby.23 Adolfo Bioy Casares, for his part, fondly recalled the times during his childhood when “el negro Raúl” had greeted him by his nickname “Adolfito”; the thought that the famous character was his personal friend “filled me with a certain pride.” Imagine his disappointment, half a century later, when he belatedly realized (as he confided to his diary in 1975) that “el negro Raúl did not actually know me.” Being quick with a name and a smile was just a necessary part of his act, part of what kept him relevant as a celebrity.24 Juan José Sebreli, an essayist and philosopher who identifies as gay, once told an interviewer that his own “fame was of the same kind as el negro Raúl’s” – an outsider fame. “Everybody knew him, everyone greeted him, he was famous. You had to sit at this man’s table at a restaurant if you hoped to matter, and yet he was an outcast (un marginal).”25 The reactionary Manuel Gálvez, finally, judged Raúl’s fame spurious and unwarranted, but no less real. Asked by a reporter in 1958 whether he was planning to publish his own sprawling memoirs, Gálvez answered bitterly that no presses or readers were interested in such “monuments of literature” anymore. Yet “more than one press would jump at the chance to publish the Memoirs of el Negro Raúl, if only they existed.”26

Raúl’s fame as a negro in twentieth-century Argentina was fueled in part by its seeming incongruity. If celebrity was an unstable condition shaped by public reputation and performance, in Argentina (as in other parts of Latin America) so was Blackness. Each of these categories was difficult to hold constant in twentieth-century Buenos Aires. Together they were mercurial, each repelling the other like magnetic poles. Black celebrity was a near-impossibility, a contradiction in terms, whether because of the public silencing of the Blackness of accomplished people of African descent or the public defamation awaiting Afrodescendants who aspired too far beyond their “station.” In Argentina, as in many other parts of the Americas, this fragile Black celebrity was further conditioned by gender, placing it even farther out of reach for Afrodescendant women than for their fathers, brothers, husbands, or sons. The remarkable case of “el negro Raúl” resonates with, and helps connect, instances of courageous self-invention across the African Diaspora, in which Afrodescendants successfully used fame, reputation, performance, masculinity or femininity, and self-invention to make spaces for themselves in societies marked by the dehumanizing legacies of racial slavery. But it also sheds light on the ways that contingent meanings of Blackness, and local or national scripts about celebrity, constrain the possibilities, rewards, and effects of fame for Afrodescendants in different places and times. Black Legend thus contributes, from the South Atlantic, to an emerging global history of the conditions of possibility of Black celebrity that, until now, has focused primarily on the anglophone North Atlantic.27

At the same time, however exceptional, Raúl Grigera’s experience as a Black celebrity in the White capital was “not too many steps beyond the more common experience” of his non-famous Afroporteño contemporaries.28 His celebrity, which forced him to contend daily with the racialized character of “el negro Raúl” largely beyond his control, was an extreme version – different in degree, but not in kind – of the experiences of other Afroporteño women and men who lived in perpetual negotiation with widespread racial narratives capable of circumscribing and deforming personal, familial, and community trajectories. Most of Raúl’s near and distant relatives, ancestors, friends, and community members were not famous (although some were). But they were exceptionally expressive protagonists of some of the major processes and events of their time: at once “extraordinary and all-too-ordinary.”29 Indeed, just as Raúl’s Black celebrity was inextricable from his place within a vibrant Afroporteño community, his and other Afro-Argentines’ histories were inextricable from the history of all Argentines. Black Legend demonstrates the extent to which Blackness, and the logic of race more generally, was intimately bound to other major social and cultural transformations in modern Argentina: the maturing of liberalism and its inordinate obsession with producing sameness, the rise of a class society and of mass politics, the evolution of Buenos Aires’ bohemian popular culture (especially the tango) and related ideas of gender and sexuality, the legal and medical histories of minority and madness, and the ebb and flow of democratic governments and related struggles over national identity. These subfields of Argentine history rarely, if ever, engage with questions of race. But Raúl’s story makes the intersection of Blackness with class, politics, popular and high culture, law, institutions of social control, gender, and sexuality in twentieth-century Argentina impossible to ignore. And it lays bare the ways that anti-Black racism, which continued unabated (if strenuously denied), thoroughly structured the purportedly non-racialized forms of social discrimination that characterize Argentina’s twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

If this history of Blackness shakes loose new histories of Whiteness in Argentina, it also enriches the broader literature on race in Latin America by framing Argentine Whiteness not (as is usually asserted) as the polar opposite of Latin American ideologies of “racial democracy” and mixture, but as their local variant.30 To continue to portray Argentina as a regional outlier, a place where Whiteness triumphed because of successful state campaigns of extermination, immigration, and demographic replacement, is to further fuel black legends of Afrodescendant and Indigenous disappearance. By the same token, telling the history of Argentine racial ideologies as if homogeneous Whiteness had been a secure outcome or a foregone conclusion since the middle of the nineteenth century, without attending to the many twists and switchbacks in the story, to the gaps between discourse and reality, and to the changing meanings of Whiteness and homogeneity, is also to do the work of aspirational racial narratives for them. As in other Latin American nations, elites in Argentina labored intensely to construct different kinds of homogeneity out of mixture, albeit with a greater – but not always obvious or unshakable – conviction that the result of mixture was Whiteness. And as in Brazil, Mexico, Cuba, or Colombia, Argentine elites congratulated themselves, along the way, that their commitment to colorlessness, mixture, and racial harmony had saved their nation from the racial strife of the United States and elevated them morally, even if it had made them somewhat less “White.”31

Like other Latin American master narratives of racial harmony, which reflected elites’ desires to produce unified nations through the assimilation or dissolution of Indigenous or African populations, Argentina’s master narrative of homogeneous Whiteness had an extraordinarily repressive side: its success hinged partly on expelling people like Raúl who, because of their appearance or behavior or both, could not aspire to Whiteness. Scholars have written eloquently about the “ethnic terror” that compelled many people of African or Indigenous backgrounds to alter, downplay, or deny physical or behavioral markers of ethno-racial difference to fit into a mold presented by dominant sectors as “civilized” and “neutral,” but patterned on White European models.32 Nor was this national obsession with homogeneity – common to many nation-states especially in their formative stages, but especially extreme in Argentina – limited to a concern with racial diversity. Over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (and arguably into the present), citizens internalized the state’s mission to surveil, control, and produce sameness through widespread mechanisms of cultural micro-“patrolling” – teasing, tormenting, casting out, or physically attacking anyone who failed to conform to social expectations around speech, dress, regional origin, political affiliation, religion, gender expression, or bodily appearance, to name just a few.33 Whiteness is not one more item on this list; it is imbricated with all of them, as is national belonging. But the obverse message in Argentina’s master narrative of racial homogeneity was that individuals of various phenotypes and backgrounds who took steps to perform Whiteness could achieve inclusion within the formally White citizenry. As in other parts of Latin America, in Argentina this inclusion was partial and insecure, and it came at a steep price for Afrodescendants: their forced invisibility as a distinct group and the entrenchment of ideas about Argentina as a country without races or racism.34

Black Legend illustrates these processes from the individual outward, reconstructing the experiences of Raúl Grigera, his family, and his community across several generations to shed light on the changing contours of, and requirements for, racialized belonging in Argentina. I hope this book’s rendering of Raúl’s many lives, both historical and fictional, will help us better understand the challenges of and opportunities for unmaking a repressive racial order that was centuries in the making. And I hope it will stand as a stark example – from an unexpected place on the margins of the Black Atlantic – of the undeniable power of racial stories to make race and unmake lives, and the urgency of putting new stories in their place.