What is the effect of environmental hazards on individual migration decisions when climate-change–related mobility is permitted by a foreign state? The stakes of this question are great (Keohane Reference Keohane2015). Although most disaster-related displacement is short term, migration related to slow-onset climate change may be more permanent and large-scale (Huang Reference Huang2023). A 2018 World Bank report projected that 143 million people from sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America will be forcibly displaced by weather events before 2050 (Rigaud et al. Reference Rigaud, De Sherbinin, Jones, Bergmann, Clement, Ober and Schewe2018).

This projection, driven by expectations of unabated global warming and inaction by the world’s highest carbon-producing economies, has inspired calls for “climate-change visas” (Huckstep and Ginn Reference Huckstep and Ginn2023) and other humanitarian accommodations for forced migrants currently unrecognized by international refugee and asylum law. Despite governments’ acknowledgment of the associated environmental phenomena, no country has yet offered permanent immigration tracks for people displaced by such disasters and hazards (but see Hurst and Butler Reference Hurst and Butler2023). A principal reason for this is that governments fear constraining their ability to limit large flows of immigrants (Brown Reference Brown2008). More fundamentally, researchers and even some activists question the relationship between migration and environmental change in the first place (Adams Reference Adams2016; Campbell Reference Campbell2014; Mortreux and Barnett Reference Mortreux and Barnett2009).

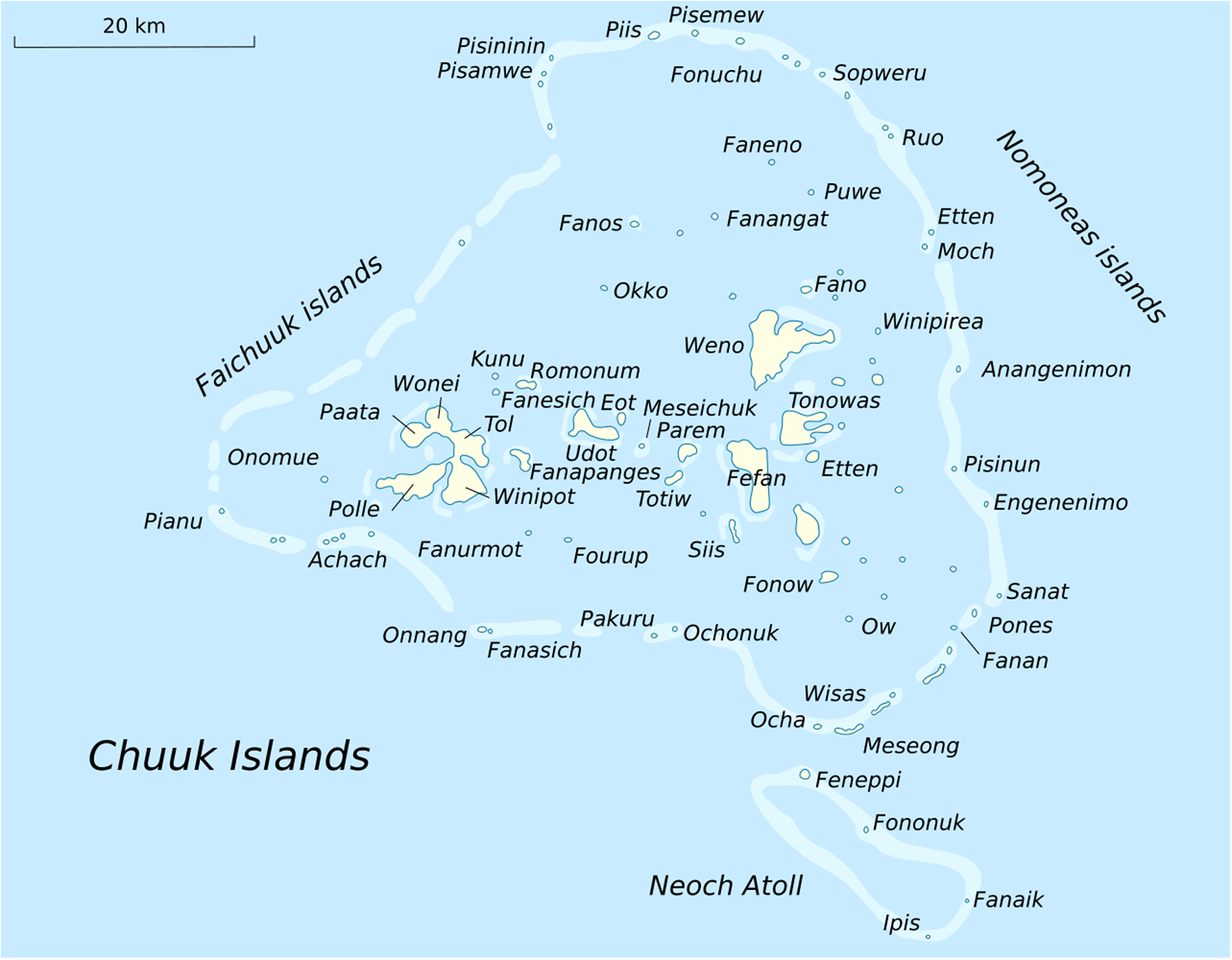

Map of the Southwest Pacific Ocean

This study leverages a full-immersion, qualitative case study and an original, large-scale survey of Chuukese citizens in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), the circumstances of which simulate the dynamics of a would-be policy environment that grants asylum to people subject to the effects of climate change. The FSM is unique in the world of sovereign countries. Owing to an exceptional treaty, citizens of the FSM can freely enter and settle in the United States as non-immigrants without visas. Micronesia’s islands are far poorer than the country to which its citizens have unfettered access. Moreover, the FSM is vulnerable to rising sea levels and intensifying tropical storms. A recent United Nations analysis found that the combination of environmental vulnerability and dependence on international flows of people and capital—tourism, remittances, and foreign investment—makes countries like the FSM among the most vulnerable economies in the world (Assa and Meddeb Reference Assa and Meddeb2021; see also Ratha et al. Reference Ratha, De, Plaza, Schuettler, Shaw, Wyss and Yi2016).

This study leverages a full-immersion, qualitative case study and an original, large-scale survey of Chuukese citizens in the Federated States of Micronesia, the circumstances of which simulate the dynamics of a would-be policy environment that grants asylum to people subject to the effects of climate change.

Even before environmental factors are considered, classical economic assumptions would expect the large-scale departure of Micronesians to the United States. Indeed, in 2021, Micronesia’s population lost approximately 21 people for every 1,000 (Artuç et al. Reference Artuç, Docquier, Özden and Parsons2015; Clement et al. Reference Clement, Rigaud, De Sherbinin, Jones, Adamo, Schewe, Sadiq and Shabahat2021). However, despite the availability of an opportunity to migrate to a more economically and environmentally secure country, the vast majority of Micronesians still remain. Such a naturally simulated setting, therefore, allows researchers to better study the effect of environmental factors on prospective migrant decision makers to better anticipate and manage future flows.

Based on unstructured interviews with more than 40 respondents in Chuuk and Honolulu, Hawai‘i—Micronesians’ principal destination—and a survey of more than 500 respondents conducted in Chuuk, we found that environmental hazards do not have a direct role in Chuukese people’s decisions to leave their vulnerable islands. Despite pervasive awareness of hazards, responses from Chuukese citizens suggest that environmental risks contextualize migration decisions but do not drive them. In general, other factors like work, health, and family obligations take precedence.

These findings affirm the conclusions of some earlier studies but with the unique validity of a setting that closely simulates the circumstances of a future climate-change refugee policy that granted entry to citizens of acutely exposed countries. This article next reviews the current state of the field and the methodological challenges of studying climate mobility. We then outline our case selection and research design and finally present key findings based on themes that emerged from our interview-based fieldwork and survey research.

STATE OF THE FIELD

Although they are unrecognized by international humanitarian law, “climate-change refugees” have been subject to many studies across disciplines, all attempting to understand the dynamics that one day may inspire changes to immigration policy making. There is near consensus that environmental factors have a role in microeconomic decisions to migrate (Warner et al. Reference Warner, Hamza, Oliver-Smith, Renaud and Julca2010); however, their salience relative to other drivers of migration (e.g., poverty, job prospects, family reunification, and illness) is disputed by different researchers and frustrated by the challenges of case selection.Footnote 1

According to recent meta-analyses based on several hundred cross-disciplinary and methodologically mixed sources,Footnote 2 the most common impacts of slow-onset environmental events are voluntary migration (both temporary and permanent) and immobility; the most common migration outcomes of fast-onset events are involuntary migration and short-term, short-distance movement (Cattaneo et al. Reference Cattaneo, Beine, Fröhlich, Kniveton, Martinez-Zarzoso, Mastrorillo, Millock, Piguet and Schraven2019). In general, migration is understood as a household strategy to diversify risk—only one form of environmental adaptation—in the context of other factors related to demographic characteristics; social networks; and historical, political, and economic conditions (Hunter, Luna, and Norton Reference Hunter, Luna and Norton2015). Although some scholars have argued otherwise (El-Hinnawi Reference El-Hinnawi1985; Gray and Wise Reference Gray and Wise2016; Myers Reference Myers1993), increases in international migration flows singularly due to climate variability are now thought to be unlikely (Millock Reference Millock2015).

Although the weight of this evidence is substantial, the validity of these data for questions related to humanitarian migration policy making is questionable because, methodologically, researchers cannot simulate prospective migrants’ choices when their mobility is no longer restricted. First, almost all studies related to international mobility focus on populations pressurized by environmental risks associated with climate change but without opportunity structures—such as multilateral treaties and visa programs—that facilitate their resettlement elsewhere. As a result, subjects’ emigration often is hypothetical and, if pursued, likely to be irregular.

Second, even among the few studies that are set in jurisdictions party to international free mobility agreements, most do not account for the possibility of domestic mobility or local adaptation (for a notable exception, see Constable Reference Constable2017). In the face of environmental hazards, alternative domestic destinations—those on higher ground or with more precipitation, for example—may provide the same refuge from disasters as those destinations abroad. Yet, scholars examining climate migration conventionally focus on domestic or international movement, as if these were mutually exclusive alternatives. Where domestic resettlement is possible, it is conceivable that future “refugee” visas would not be provided.

Extensive research also has shown the various ways that communities subject to environmental hazards adapt locally to avoid displacement. Adaptation strategies may involve economic choices such as tapping savings accounts, selling assets, taking on debt, and accessing international development assistance. These strategies may involve social adjustments such as participating in risk-reducing networks (Wodon et al. Reference Wodon, Liverani, Joseph and Bougnoux2014) and agricultural innovations, including changing livestock species, implementing feed-conservation measures, and introducing drought-tolerant and fast-maturing varieties of crops (Karanja Ng’ang’a et al. Reference Ng’ang’a, Stanley, Giller, McIntire and Rufino2016; Kattumuri, Ravindranath, and Esteves Reference Kattumuri, Ravindranath and Esteves2017). Viewed through this lens, emigration represents less of an adaptation strategy and more of a failure to adapt.

Recent publications highlight the adaptations that Micronesians have made to account for environmental degradation. When islanders were facing slow-onset degradation and typhoons such as Chataan (2002), Haiyan (2013), Maysak (2015), and Wutip (2019), researchers recognized their resilience and resourcefulness—a result of their understanding of the local ecosystem and kinship networks that offset and spread their exposure to environmental risks, despite their isolation and limited land (Chuuk Joint State Action Plan on Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change 2017; Perkins and Krause Reference Perkins and Krause2018). Nevertheless, environmental effects compound preexistent phenomena that threaten the health and well-being of communities already subject to resource scarcity and internal conflict (Grecni, Bryson, and Chugen Reference Grecni, Bryson and Chugen2023, 26).

Recent research into the relationship between environmental degradation and conflict posits that climate change may trigger violence under certain political conditions—a “climate-conflict” link in complex emergencies that together can generate refugee flows. Equally, conflict also may hold deleterious effects on states’ environmental management, producing grave vulnerability. However, international legal conventions continue to limit definitions of humanitarian status exclusively to matters of war and persecution (Bergholt and Lujala Reference Bergholt and Lujala2012; Besley and Torsten Reference Besley and Torsten2011; Brancati Reference Brancati2007; Keen Reference Keen2008; Nel and Righarts Reference Nel and Righarts2008; Slettebak Reference Slettebak2012).

RESEARCH DESIGN

The unique circumstances of Chuuk in the FSM simulate household-level choices if the link between environmental degradation and humanitarian vulnerability were to be acknowledged in international law, sufficient to justify a new class of “climate-change visas.” Like many Pacific islands, Chuuk—one of four states in the FSM—is subject to various environmental hazards, including sea-level rises and king tides that have begun to flood coastlines and contaminate soil; intensifying typhoons and tropical storms; and droughts associated with extended heat waves. However, what distinguishes Chuuk from other vulnerable regions elsewhere in the world is the FSM’s membership in the Compact of Free Association (COFA) agreement. Under this agreement, the American government has given Micronesians—along with Palauans and the Marshallese—economic assistance and free mobility (including work authorization) in the United States in exchange for full defense authority over their vast and strategic ocean waters since 1986 (US Citizenship and Immigration Services 2020).

Furthermore, unlike other countries subject to international mobility treaties, the topographic and social dynamics of Micronesia mean that people exposed to environmental risks are less able to move domestically. By land area, Micronesia is a small country and most of the population lives near sea level, exposed to environmental risk. Although the population centers of the four states—Chuuk, Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Yap—are located on volcanic “high islands,” most of their elevated regions often are impassably steep or covered in thick jungle. Outer islands and lagoon islands are mainly low-lying atolls set along the rim of ancient, submerged sea volcanoes.

Socially, the outer islands and lagoon islands are each associated with a specific family or kinship-based clan, and they effectively are closed to domestic migration except when there is intermarriage between them. “High-island” population centers do mix people from different clans; however, long-term domestic migrants often join relatives in cramped quarters and must find paid work, which limits the prospects for those who are less educated or less connected. Micronesian courts already are backlogged with cases contesting land claims as land becomes less fertile or inhabitable and matrilineal traditions of inheritance become complicated by Western concepts of the nuclear family (Hezel Reference Hezel2001, 33–45; Reference Hezel2013, 35).

Map of Chuuk (Encyclopedia Britannica)

These circumstances satisfy the criteria of advocates who are pursuing “climate-change visas” and confront Micronesians with decisions that approximate those of would-be “refugees” eligible for entry into another country. As in other states subject to severe environmental risks and hazards, Micronesians must weigh additional push-and-pull factors, including the promise of a higher and more stable income abroad, the presence of immediate family members in the United States, and sometimes severe medical conditions that cannot be treated at home. At approximately $3,992.2, Micronesia’s GDP per capita is similar to that of Bolivia (World Bank 2023), and its hospitals are unable to address most severe health conditions.

With environmental catastrophe seemingly imminent, Micronesia is perhaps equally remarkable for the number of people who choose to remain on the remote islands, given their strong cultural values tied to a sense of obligation to and inheritance of the land. Whereas the country has among the highest net migration rates globally (Central Intelligence Agency n.d.), most other nations do not have carte blanche access to the world’s wealthiest country. Micronesia’s net migration rate was -4.19 per 1,000 people in 2023 (Macrotrends n.d.). This rate has decreased every year since a peak of -15.89 per 1,000 people in 2008. With the implementation of the COFA in 1986, most migration from the FSM between 1990 and 2017 was to Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, or one of the 50 American states (Hezel and McGrath Reference Hezel and McGrath1989; World Mapper n.d.). With the economic downturn in Guam in the late 1990s, Hawai‘i and the US mainland became popular destinations, with 20 states and territories currently home to at least 1,000 migrants from the three COFA countries (US Government Accountability Office 2020).

Nevertheless, migration to the United States is not uncomplicated. Despite advantages associated with job availability, relative wages, health care facilities, and infrastructure, Micronesians in the United States struggle to adapt to America’s individualist ethos and suffer extensively documented discrimination and poverty (Drinkall et al. Reference Drinkall, Leung, Bruch, Micky and Wells2019; Inada et al. Reference Inada, Braun, Mwarike, Cassel, Compton, Yamada and Sentell2019; Kaholokula Reference Kaholokula, Miyamoto, Hermosura, Inada, Benuto, Duckworth, Masuda and O’Donohue2020). As such, there is a tradeoff between profound social and economic displacement, on the one hand, and a technologically advanced society with the proximity of loved ones who have already moved there, on the other.

How do environmental hazards factor into prospective migrants’ decision to emigrate? To address this question, this study presents the results of three weeks of full-immersion fieldwork in Chuuk—including the main island of Weno and the lagoon islands of Eot, Parem, Patta, Pisiwe, Polle, Tol, and Tonoas, as well as Honolulu, Hawai‘i, where a large number of Micronesians have resettled during the past few decades. We include data from Hawai‘i to contextualize prospective migrants’ viewpoints with reflections of Micronesians who made the choice to emigrate and continue to interface with friends and relatives in their country of origin. These unstructured interviews took place in various locations—inside people’s homes, workplaces, and public spaces—and were of variable duration. Respondents were elites in their communities—shop owners, members of a prominent family, village elders, and local leaders—and were interviewed in December 2022, January 2023, and December 2023.

How do environmental hazards factor into prospective migrants’ decision to emigrate? To address this question, this study presents the results of three weeks of full-immersion fieldwork in Chuuk—including the main island of Weno and the lagoon islands of Eot, Parem, Patta, Pisiwe, Polle, Tol, and Tonoas—as well as Honolulu, Hawai‘i, where a large number of Micronesians have resettled during the past few decades.

Exclusively in Chuuk, we also conducted a survey of 502 Micronesian citizens from multiple islands. The survey was conducted by four enumerators recruited from the local population between January and September 2023. Although most surveys were conducted in English, enumerators translated portions into Chuukese on request. The enumerators were trained to administer the Qualtrics-based surveys using researcher-provided iPads. Given the challenges of conducting surveys in the Chuukese context, the sampling was not probabilistic. Instead, enumerators drew respondents from a diversity of public areas visited by the widest groups possible: a bustling boat harbor, a medical center, a popular supermarket, Chuuk International Airport, government facilities, churches of different denominations, and multiple villages and islands. The variety of locations in which respondents were recruited resulted in a sample with characteristics that reasonably resemble the FSM population. Online appendix A provides further details on the survey, and online appendix B provides details on the variables presented in the analysis. Our analysis of the survey data is based on bivariate analysis for ease of exposition and integration with our qualitative data. Online appendix C presents additional results based on multivariate linear probability models. These results are strongly consistent with those discussed in this article, thereby serving as a robustness check (Núñez et al. Reference Núñez, Gest, Drinkall and Micky2024).

All respondents explicitly consented to participate in this study, and those in Chuuk were thanked for their time with culturally appropriate gifts. The subject matter, although salient, was not controversial or taboo, and respondents understood that they could elect to end interviews at any time without penalty.

FINDINGS: FROM THE FRONT LINE

How do environmental hazards factor into prospective Micronesian emigrants’ decision making? Our central finding is that, as a general matter, they do not. Although the Chuukese we interviewed were (1) acutely aware of these risks, their decision making was (2) often fatalistic about their personal and environmental security, and—even among those who otherwise might depart—(3) driven by the obligation to stay close to their families. This section describes each of these dynamics.

Unsustainable Subsistence

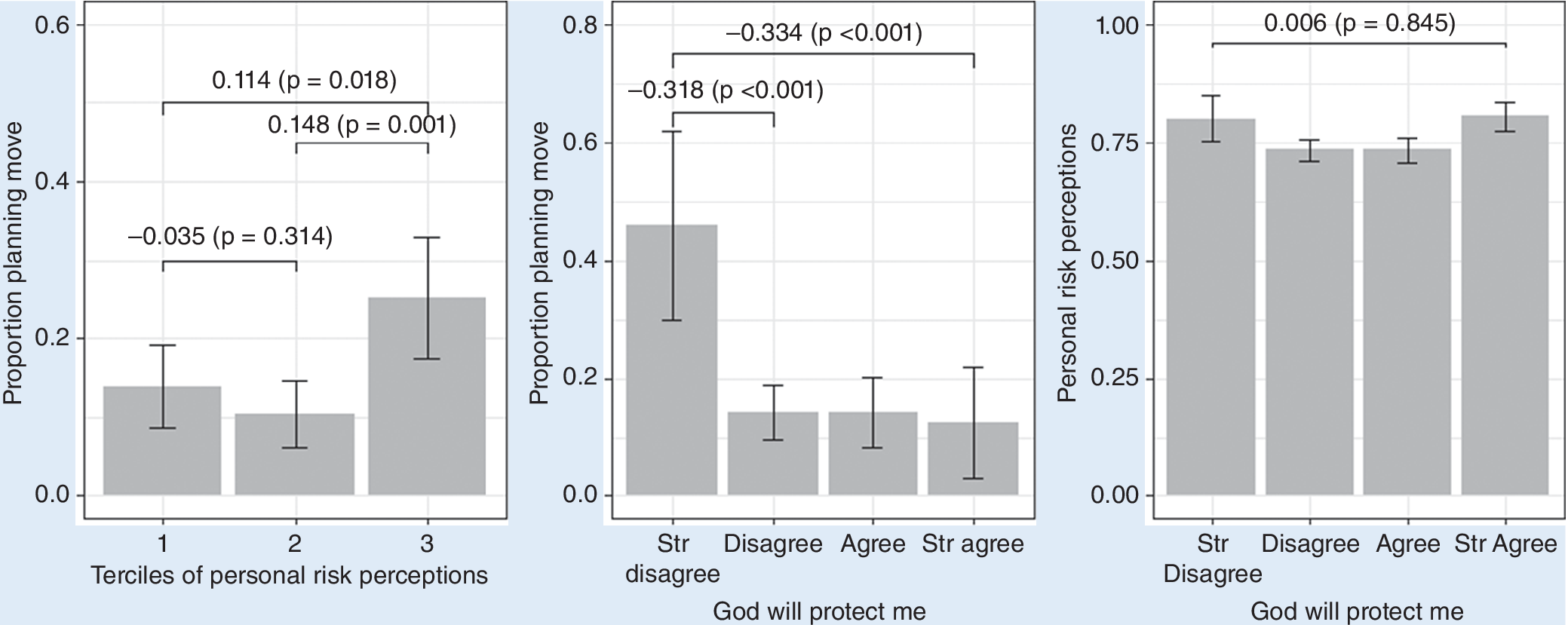

Chuukese respondents were generally aware of environmental risks, even if there often was ambiguity about its drivers and probability. In our survey of 502 respondents living in diverse topographical settings across the main island of Weno and Chuuk’s lagoon islands, there was a clear connection between heightened perceptions of environmental risk and living on low-lying land. Those within the highest tercile of risk perceptions were 18.7 (p=0.001) percentage points more likely to live on low-lying land than those in the lowest tercile (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Risk Perception and Low Land

Respondents described droughts and floods, coastal erosion, damage to homes and crops, and salty drinking water. A municipal mayor stated that his constituents now must dig shallow wells during times of drought to access potable water. Another mayor described rising sea waters that now cover taro patches and, for the first time, his island’s main road. A village elder, familiar with the term “climate change,” recounted the effects of Typhoon Chataan in 2002 that triggered fatal mudslides and covered taro patches, some of which have not yet recovered. A village pastor stated that parishioners owning land near the sea have had to raise their houses on blocks. To cover the costs for repairs, some family members left to find work in the United States.

Parem Island is one of the low-lying islands at the front line of global climate change. It is a flat, triangular island southwest of Weno (the FSM’s second-most populated island and the capital of Chuuk), about a 12-minute boat ride from its “boat pool” harbor. The adjacent settlements of Pekisere and Fanip—two of seven on Parem—abut the coastline with barely any land between its dwellings and the coconut-studded beach. As the tide rises, water passes into the island’s recesses by its cemetery. Rising waters recently submerged the villages’ dock, a crude concrete pier whose extreme end is now covered by incoming waves. The beach once extended 30 feet farther out into the sea.

Islanders spoke of a recent king tide when the ocean swelled over Parem’s southern banks, invaded the villages, and flooded the island’s interior vegetation—ruining the freshwater taro and tapioca patch and nearly killing banana trees. Almost none of the root vegetables survived, and villagers currently rely on crops that they have cultivated on the nearby island of Eun during the past 15 years.

When we first arrived on Parem, most of the young men were on Eun gathering fresh taro and coconut crabs for their supper. Historically, the Parem islanders only visited Eun to collect food for weddings, funerals, and church holidays. These days, they go every two weeks, sometimes returning empty-handed. However, that morning, they went to Eun because villagers had spotted two unknown boats anchored at the island and they were concerned that intruders were harvesting food without permission, a violation but also an indication of how precious the island’s food reserve is. By the time the boats from Parem arrived, the poachers were gone.

Parem is not an exception in Chuuk. Similar stories are told on Patta, Polle, and Tol, where most taro patches are at sea level. The coastline of the islets of the Losap atoll also is attenuating as Pacific waters creep closer to its homes. Like Parem, Losap islanders now harvest their food from a nearby island because they can no longer grow taro or breadfruit onshore.

“How important are the reserve crops on Eun?,” we asked Parem’s 69-year-old elder, Norsiana Welle Akira.

“We now depend on it,” she told us as she washed sea cucumbers that her niece recently had harvested from the seabed.

Sea cucumbers are a delicacy. After the outer shell is removed, the remaining black exterior is skinned off with a sharp metal blade. The gnarly, slimy white strings are washed; mixed with vinegar, lemon, and garlic; and then packaged into recycled bottles for sale at the market—approximately USD $3 per bottle wholesale. With weak income prospects, Parem’s villagers continue to rely on subsistence farming—but subsistence farming relies on improving environmental prospects. The majority of Micronesians continue to place that improbable bet.

“God Will Protect Me”

“‘Climate change’ is a foreign term,” stated Josie Howard, the founder and executive director of We Are Oceania (WAO), a non-governmental organization based in Honolulu that provides social services to newcomers from Micronesia in Hawai‘i. Howard herself was raised on a remote Chuukese atoll. She came to Honolulu on a scholarship from the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, after a local priest helped finance her secondary education at Xavier High School in Chuuk. She is a tireless, vociferous defender of Micronesians—Hawai‘i’s poorest minority—and regularly advocates on their behalf to public officials. Our interview was delayed because Howard was finding housing for a family of recent arrivals. She paced barefoot around her office, making calls to local shelters.

Howard thinks her native island will be submerged within 60 years. Especially among the most vulnerable islands, respondents were acutely aware of the precariousness of their future existence. Norsiana Welle Akira described stacking bags of rice on the shore to protect against encroaching water on Parem. “If we sink, we sink. What can I do? [The island] will sink with the people.” In quiet defiance, she stated, “The land is so precious. I will stay.”

“I can see the impacts of climate change,” Howard told us. “But, in our culture, we independently know that nature changes and it depends on how we treat it. I think a lot of people feel powerless because it’s not directly attributable to their behavior. Some believe the promise God gave to Noah that He would never send another flood.”

Indeed, when we interviewed respondents in Chuuk about their level of concern about the myriad environmental hazards facing their islands—even among those who agreed that climate change is the greatest challenge facing Micronesia—some stated that they do not worry about climate change because “God will protect me.”

In our survey research, we found that individuals in the third (highest) tercile of risk perceptions are 11.4 (p=0.018) percentage points more likely to be planning to migrate than those in the lower tercile of risk perceptions. We also found clear evidence that the notion that “God will protect me” is negatively related to plans to migrate: those strongly doubting God’s protection from environmental change were 33.4 (p<0.001) percentage points more likely to have made plans to migrate compared to those reporting strong faith.Footnote 3 Importantly, respondents’ perception of their own exposure to environmental risk does not vary substantially with belief in God’s protection from those risks (see the left panel in Figure 2). That is, respondents who believe in God’s protection from environmental challenges do not negate or minimize the associated risks; they simply believe that the Lord will shield them. Thus, our survey results strongly suggest that faith in God’s protection attenuates the likelihood of Micronesians’ departure.

Figure 2 Risk Perception, Belief in God, and Migration Plans

Whereas this reflects the deep spirituality of Micronesians, almost all of whom identify as Christian, it also reflects Micronesians’ strong propensity for divination to explain and justify loss and uncertainty. Some people even personalize their misfortunes by attributing them to someone’s sorcery or ill will. Interviewees in Chuuk—which has been colonized by the Spanish, Germans, Japanese, and Americans just since 1885—referred back to their comfort with and adaptation to uncertainty and matters beyond their control.

Back on Parem, the island elder, Norsiana Welle Akira, continued: “King tides are a major issue here. It severely affects our plantation. Every time [the sea water] comes onshore, it takes out all the taro and tapioca, and it kills my banana trees. All the leaves turn yellow; they look dead. Only if there’s a lot of rain, [the banana trees] may survive to bear fruit.”

“What is causing the sea to come in like this?,” we asked.

“I don’t know!” she exclaimed exasperatedly. “They tell me maybe it’s what they call the ice melting at the North Pole, I don’t know. Climate change, they say.”

“What can you do about it?”

“I wish I had enough money to build a sea wall,” she said, as she nibbled on chofar, the spongey, tangy, crunchy remains of an overripened coconut. “Sometimes I talk about it with my daughter.”

Welle Akira peered back at her home. Like others around Chuuk, it has a corrugated-metal retaining wall and roof, and open-air windows wrapping around the sides. Mattresses lined the floor—many in each room. Cooking areas are outdoors and communal. Men forage and fish and women prepare the meals over mahogany afor wood fires.Footnote 4

“I wish I knew if we can stay on our island forever,” she lamented. “But because of the sea, if it is like this every year, we can’t stay. And I’m so scared someone will one day come and tell us that we must leave because soon we’ll be underwater. I want our young to stay, but a lot of them already go abroad for jobs and school.”

Family Ties

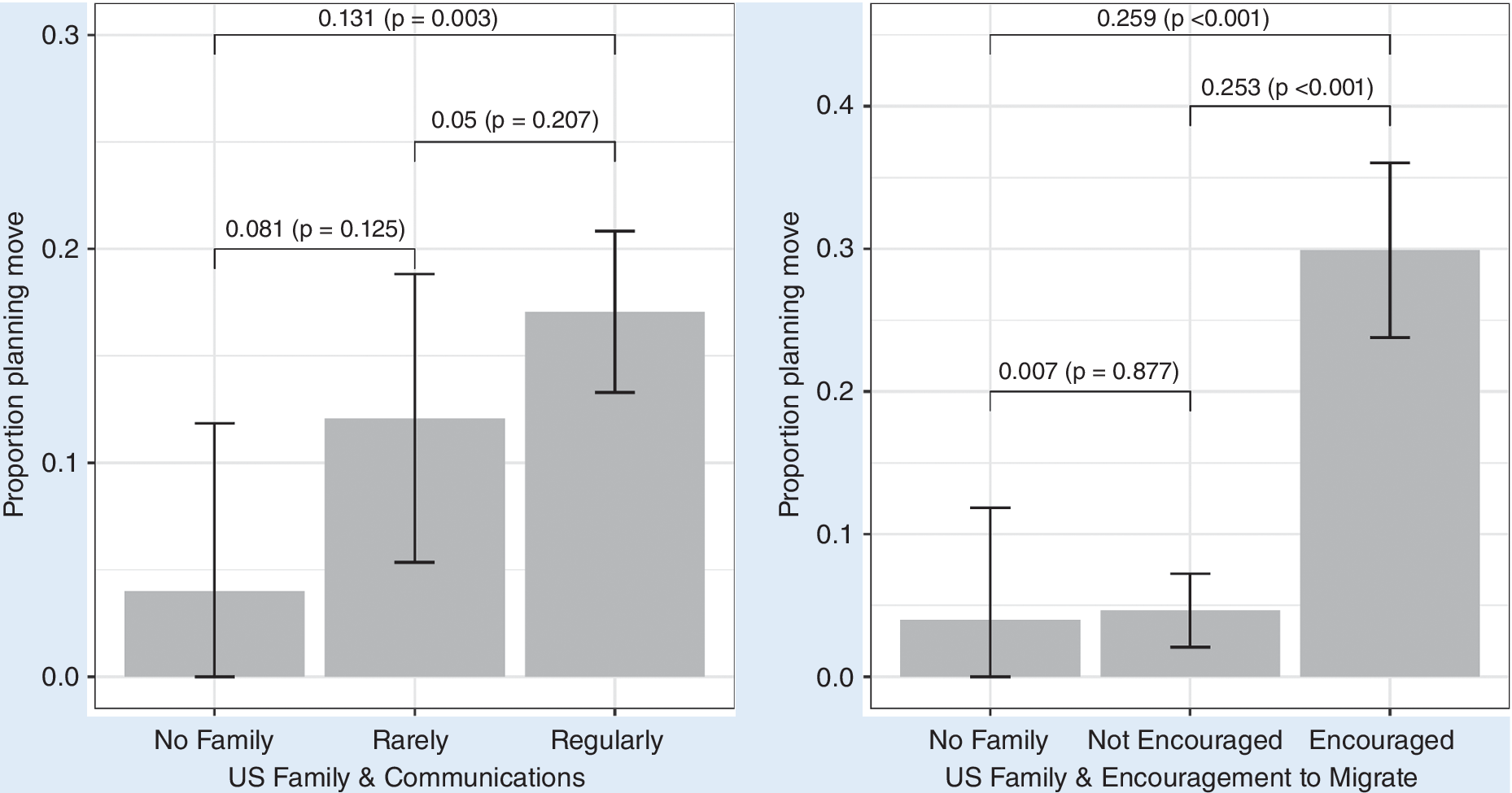

In survey research, we identified a correlation between heightened perceptions of environmental risk and a desire to migrate (see Figure 2). However, family ties are what inspire many people to leave or to stay (Figure 3). Respondents who reported having family in the United States were more likely to have made plans to move. Those without family in the United States were 13.1 (p=0.003) percentage points less likely to have made plans to move than those who communicate regularly with family in the United States. Relatedly, respondents who were encouraged to move by relatives who live abroad were 25.9 (p<0.001) percentage points more likely to be planning a move than those who were not encouraged or did not have any family abroad. Notably, the proportion that was planning a move among those without family or whose family has not encouraged them to move was virtually the same, which suggests the influence of a family’s endorsement in departure decisions.

Figure 3 Connections with US Family and Migration Plans

In Micronesia, family—and the more extensive kin group—bestows group identity, material security, personal worth, and moral scaffolding (Hezel Reference Hezel2013, 167). Kin groups are associated with specific islands and provide a source of separate, collective identity that supersedes more regional, national, or ethno-religious forms and acts as a protective refuge from non-kin social, economic, and civic relations. However, just as families may encourage Chuukese relatives to join them abroad, they also obligate many to remain despite the economic, health, and environmental risks. In short, family ties cut both ways.

Renee Aisek spent a decade in Hawai‘i, where she worked primarily as an aircraft cabin cleaner and ticketing agent for United Airlines, which offers free trips back to Micronesia as an employee benefit.Footnote 5 She returned to Chuuk when her husband was injured in Honolulu and required what she called “local healing.” During their months back on Weno, Renee began working for her uncle, the mayor of Tonoas Island and owner of a hotel at Weno’s southwestern extreme. When her husband’s condition improved and they considered a return to Hawai‘i, her uncle urged her to continue working at his hotel. Reluctant to decline a request from a family elder, she obliged and has remained on Weno ever since. She also found a job with United Airlines on Weno to supplement her income.

Sammy Aisek (no relation to Renee) graduated from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, enrolled in a master’s program there, and was dating his Honolulu-based Micronesian girlfriend when he was asked by family members to return to Chuuk in 2019. His sister, Mae, who had been running the family business (Deal Fair, one of the largest supermarkets on Weno) was caring for three small children and needed assistance with the daily grind of retail. His older siblings Rowena and Junior were already running the affiliated family business in Honolulu: Deal Fair Hawai‘i, a convenience store popular with the Micronesian diaspora. So Sammy, the family’s youngest child, quit his studies and began commuting back and forth from Chuuk to Honolulu. He can see no way back to living in the United States.

The sacrifices of Renee Aisek and Sammy Aisek reflect the way that the Chuukese embed their decisions to migrate in broader considerations of family solidarity and welfare. There is no concept of individual action or individual responsibility in Micronesian culture (Hezel Reference Hezel2013, 25). Therefore, a community-altering decision to emigrate is considered inside a superseding social context. Correspondingly, the loss of habitat is a collective tragedy requiring collective adaptation.

FINDINGS: PUSH-AND-PULL FACTORS

Although Chuukese awareness of growing environmental hazards is pervasive, substantial uncertainty surrounds the extent to which environmental considerations have any role in household-level choices to migrate. The principal reason is that there are many other concurrent push-and-pull factors: (1) economic drivers and educational opportunities, (2) family matters, and (3) health care needs.

Although Chuukese awareness of growing environmental hazards is pervasive, substantial uncertainty surrounds the extent to which environmental considerations have any role in household-level choices to migrate. The principal reason is that there are many other concurrent push-and-pull factors: (1) economic drivers and educational opportunities, (2) family matters, and (3) health care needs.

“Work for Money”

Chuuk, and particularly its outer islands, was one of the last holdouts to the logic of global capitalism. Some people began to “work for money”—as opposed to subsistence or bartering—only within their lifetime. The need for income generated by paid work was triggered first by the arrival of and eventual dependence on foreign imports and then later when migration to population centers weakened clans (Hezel Reference Hezel2001). More recently, since the Micronesian government established mobile internet and phone towers to even the outermost islands, the Chuukese—almost all of whom have Facebook accounts—often are aware of foreign consumer products and alternative lifestyles, particularly in the United States.

As income has become a greater necessity for families, more young people have ventured to the United States. Although Hawai‘i, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands have long been destinations for Micronesians, new communities have been established in Portland and Salem, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; Southern California; Denver, Colorado; Corsicana, Texas; and Kansas City, Missouri. Despite their distance and alien climates, Texas and Missouri have a much lower cost of living than Hawai‘i. In addition to financial remittances, Micronesians living abroad share information about jobs and educational opportunities. Many regularly return to Chuuk with as many as a dozen pieces of luggage containing everything from bottles of cologne to meat stored in iceboxes. When they exit Weno’s single airport gate, members of the diaspora are greeted with shell necklaces and fragrant leis made of frilly green pala flowers, slices of sweet acacia fruit, and colorful plumeria and leyun blossoms.

Rather than pursue jobs in aviation, hospitality, or food production, a number of Micronesians join the US military. Despite not being US citizens, COFA nationals are eligible for service, and the US armed forces regularly recruit from Micronesian high schools.

“It’s about security,” Junior Aisek said, standing behind the counter at Deal Fair Hawai‘i. “We know there will be someone to meet us, care for us, give us a place to sleep. The military acts like a family member.”

Our survey results demonstrate that economic concerns are important determinants of a desire to migrate Figure 4. Although there is no difference in migration intentions between those with and without a job, jobless respondents who were actively seeking a job were 19.1 (p=0.001) percentage points more likely to plan to migrate. Additionally, among respondents with a job, those looking for a new one were 11.4 (p=0.027) percentage points more likely to plan to migrate than those who were not looking. There also was a clear correlation between respondents’ family income (excluding remittances) and their desire to migrate. Those with an income less than USD $250 per month were 12.6 (p<0.001) percentage points more likely to plan to move than those with the highest incomes (i.e., more than USD $1,000 per month).

Figure 4 Jobs, Income, and Plans to Migrate

Kith and Kin

Nevertheless, most Micronesians can and prefer to rely on actual members of their enormous families to welcome, integrate, and house them abroad—just as Junior did. The Chuukese frown on declining requests of help from family. As a result, it is not uncommon for six to eight people residing in a one-bedroom apartment in Honolulu, where the square-foot cost of residential property is among the highest in the United States (Federal Reserve Economic Data 2023). A substantial number of Hawai‘i’s growing population of homeless Micronesians have been evicted by landlords for exceeding a residential unit’s maximum capacity.

Despite the challenges of surviving as working-class immigrants in high cost-of-living American destinations, many Micronesians continue to emigrate to rejoin family members abroad. Even among those living at the edge of poverty, many choose to stay abroad—due more to family obligations and the comforts of a developed country than from any concern about climate change.

Rasty Papa, a Chuukese hotel security guard and chauffeur for the past 35 years, has stayed in Honolulu to help look after her grandchildren. She is acutely aware of climate change, but she had recently built a new home on her native island in Pafeng—a small atoll, highly vulnerable to sea-level rise and typhoons.

“It’s in God’s hands,” she said, lifting both of her palms upward above her head. “My island is very small, you know, I can see from one side to the other. But it also has survived the sea and typhoons for this long, so someone is looking out for us.”

“Mostly We Are Sick”

Despite the pull of money, family, and refuge from climate change, health care needs often override all other considerations. Even in Micronesia’s population centers, hospitals are in such poor condition and physicians are so scarce that the most common life-threatening conditions—including heart failure, stroke, cancer, and even diabetes—cannot be treated properly. Once a diagnosis is made, the decision to leave the island often is clear. The FSM government proactively refers and subsidizes some cases to the United States.

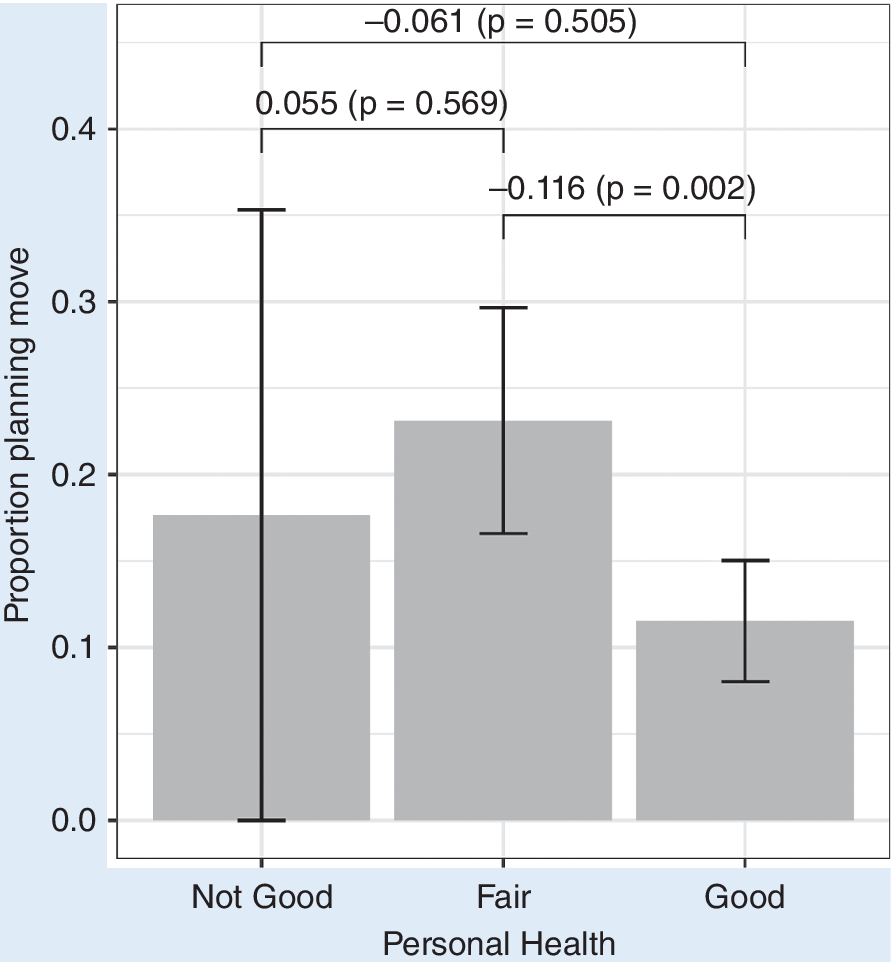

In our survey research, respondents who reported being in poor health were 5.5 percentage points more likely to indicate migration plans than those in good health; however, this correlation is not statistically significant (Figure 5). Respondents who reported sometimes requiring medical attention were 11.6 (p=0.002) percentage points more likely to have made emigration plans than those who reported good health.

Figure 5 Health Status and Plans to Migrate

“Mostly we are sick,” said Aritay Severino, a social worker at WAO in Honolulu, who advises islanders about how to access medical care as well as public services, schools, housing, and food stamps in Hawai‘i.

Micronesians are prone to hypertension and obesity because, with increased American trade over time, they have developed an appetite for processed, sugary foods and canned meat and fish. It is not simply that tastes have changed; because local agriculture has yet to be industrialized, many Micronesians rely on cheap, imported food. It is expensive to fly in fresh produce and meat, and not all families have refrigerators; therefore, processed and canned goods are more widely available and affordable. Chuuk’s supermarkets almost exclusively offer packaged imports, and any fresh fruits and vegetables often are in poor condition.

“We think rice is better than taro,” said Josie Howard of WAO. “We sell fresh fish to buy a can of mackerel.”

Medical conditions often are what keep many Micronesians from returning home.

“People come [to Hawai‘i] and wait for the sick to heal,” Howard added. “They get hooked into an endless cycle of medical appointments. They’re always waiting for the next checkup.”

CONCLUSIONS

Taken together, evidence from our fieldwork exhibits the minor role that environmental risk plays in Chuukese decisions to leave their vulnerable islands, despite their acute awareness of the hazards and their carte blanche access to the United States. Pervasively, other factors including work, health, and family obligations take precedence in life-altering migration decisions. Our findings suggest that those who are acutely vulnerable to environmental degradation are not driven to emigrate, at least not until the occurrence of an environmental disaster.

If any government were to provide a form of asylum to people confronting such slow-onset or even fast-onset environmental disasters, our findings suggest that other considerations may motivate people to apply. Some readers may be concerned that this evidence undercuts the argument for Micronesians’ (and others’) humanitarian legal status. However, it is important to emphasize that migrants’ primary motivations do not change the fundamental vulnerability of people originating from countries that are subject to environmental disaster. Indeed, personal and financial aspirations and a desire to reunify with family members do not change the humanitarian status of other forced migrants who flee oppression and persecution.

Perhaps more consequentially, our findings suggest that—contrary to many governments’ concerns about controlling the flow of climate-change refugees—many qualified asylees nevertheless would not apply for asylum. Various considerations keep many would-be migrants from departing. Strong Chuukese kin-group ties keep relatives, even extended family, in the country. Furthermore, a sense of equilibrium has settled in countries that are a party to the COFA. There is no urgency to migrate because prospective migrants are reassured that the option to do so will remain available. (Indeed, the governments of the United States and Micronesia renewed their agreement in 2024.)

As in any case study or simulation, it is reasonable to expect different dynamics in other settings subject to environmental degradation, particularly where irregular migration is facilitated (e.g., The Northern Triangle) or where political factors also may justify a traditional asylum claim (e.g., Sudan and Somalia). Researchers would do well to study countries with weaker adaptation strategies, weaker norms incentivizing continued residency, and different environmental risks, but there are few with circumstances that facilitate emigration more than Micronesia. More beneficially, researchers might study more precisely the relative weight of different push-and-pull factors when people’s choices are pressurized by the risk of environmental disaster. Our findings ground the hypotheses that these investigations would test to better understand human mobility in a new global climate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was generously funded by the Institute for Humane Studies. The authors profoundly thank Manuel Rauchholz, Sotto and Dora Rasauo, Francis X. Hezel, Jeanne Hoffman, Jocelyn Howard, Alex Aleinikoff, Jack A. Goldstone, and many others for their invaluable insights and for fostering cross-cultural connections. We also are grateful for the tireless efforts of our polling team: Jenny Theodore, Ryann Irons, Leilani Rosokow, and Pius Olopei. Most of all, we express our deep gratitude to the people of Micronesia for graciously welcoming us onto their islands and into their homes.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PUGXJG.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096524000246.