Introduction

Traditional cultural practices are deeply entrenched in many cultures and societies across the world and mirror perceived values and beliefs held by its members. While many indigenous practices are useful to its populace, others can be detrimental, with women and children being the most vulnerable (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, 2015). Two commonly linked harmful practices that have received considerable attention and which are pervasive in sub-Sahara Africa (Ahinkorah et al., Reference Ahinkorah, Hagan, Ameyaw, Seidu, Budu and Sambah2020) are female genital mutilation (FGM) and girl-child marriage (Karumbi & Gathara, Reference Karumbi and Gathara2020). FGM has often been related to girl’s/women’s eligibility for marriage and has been shown to be associated with the formation of formal partnerships for girls under the age of 18, defined as ‘child marriage’ (Varol et al., Reference Varol, Fraser, Ng, Jaldesa and Hall2014; Population Reference Bureau, 2018). These traditional practices not only negatively impact on the well-being of girls and women in sub-Saharan Africa, but also threaten their progress and quality of life (Karumbi & Gathara, Reference Karumbi and Gathara2020). FGM and girl-child marriage are social practices that function alone, but can be related to each other at different levels (Mackie & LeJeune, Reference Mackie and LeJeune2009).

According to UNFPA (2012), 30 countries in sub-Saharan Africa have a girl-child marriage incidence rate of 30% or higher. It is projected that 15 million girls are likely to enter into marriages before the age of 18 in sub-Saharan Africa, and without practical measures to halt girl-child marriage, a large number will be engaged before the age of 18 – an increase from the present estimated 720 million to 1.2 billion by 2050 (UNFPA, 2014). A recent study has shown that the overall prevalence of FGM among women in sub-Saharan Africa is 51.7%, with the largest proportion in Guinea (96.1%) and the lowest in Niger (4.2%) (Ahinkorah et al., Reference Ahinkorah, Hagan, Ameyaw, Seidu, Budu and Sambah2020).

FGM is regarded as a rite of passage into womanhood in many high-prevalence countries, and has strong ancestral and socio-cultural roots (Williams-Breault, Reference Williams-Breault2018). It has been linked to girl-child marriage due to it being a rite of passage to maturity (Karumbi & Jacinta, Reference Karumbi and Jacinta2017). FGM and girl-child marriage, as traditional practices, are often connected by a wide range of socio-cultural drivers such as the maintenance of family values (i.e. maintaining dignity and honour), preservation of girls’ virginity before marriage, promoting fidelity within marriage, societal integration of the girl and family and the offer of monetary assurance to those within the poorest wealth quintile of society (Boyden et al., Reference Boyden, Pankhurst and Tafere2012). Furthermore, both FGM and girl-child marriage have similar undesirable outcomes, such as increased risk of maternal and newborn death, delivery difficulties, social isolation and intimate partner violence (Karumbi et al., Reference Karumbi, Gathara and Muteshi2017).

Research using recent data from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys providing nationwide representative samples of women aged 15–49 in ten countries in sub-Saharan Africa has shown that FGM and girl-child marriage vary markedly by country, region and/or ethnic affiliation (Population Reference Bureau, 2018). Among sub-Sahara African women who report girl-child marriage, the proportion who have undergone FGM is higher than among those who do not report girl-child marriage (>50%), with significant variations in Burkina Faso, Egypt, Kenya, Senegal and Sierra Leone. Similarly, in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan, girls and women who report both FGM and girl-child marriage represent the largest cohort. However, girls and women who report FGM without girl-child marriage constitute the second largest subgroup. Other studies in Somalia (World Vision UK, 2013, 2014) and Ethiopia (Boyden et al., Reference Boyden, Pankhurst and Tafere2013) have also shown a direct relationship between the two practices, with FGM being seen as a transition of a girl from ‘childhood’ to ‘adulthood’, which then facilitates girl-child marriage. These studies show the similarity of causes or underlying drivers behind FGM and girl-child marriage.

Given the overall serious negative consequences of FGM and girl-child marriage, such as poor health, unintended or early pregnancy, pregnancy difficulties, multi-morbidity and mortality, providing updated empirical evidence on subnational variations and trends in the two variables, and assessing their potential linkages to indicators such as education, residential status, age, ethnicity and wealth quintile, could help map context-specific interventions and inform policy initiatives. Using DHS data from twelve selected countries in sub-Sahara Africa, this study sought to investigate the association between FGM and girl-child marriage by examining their possible correlates and making comparisons across selected countries.

Methods

Data source

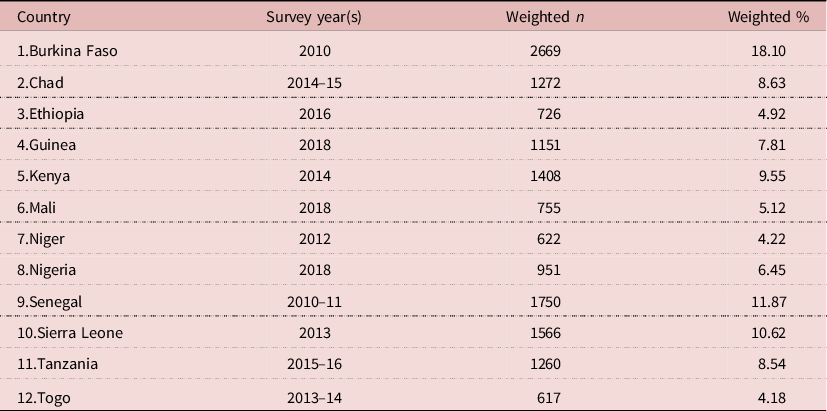

The study pooled DHS data from twelve sub-Saharan Africa countries covering the period from January 2010 to December 2018. The inclusion criteria in the selection of countries was that they had a recent DHS survey (2010–2018) with data on girl-child marriage and FGM. The women’s file (IR) which gathers data from women aged 15–49 years on significant indicators related to children’s and women’s health, including girl-child marriage and FGM was used (Corsi et al., Reference Corsi, Neuman, Finlay and Subramanian2012). The DHS uses a stratified sampling approach, which is done in two stages from a nationally representative sample. Details of the sampling process has been provided in a previous study (Aliaga & Ruilin, Reference Aliaga and Ruilin2006). This study included a total of 14,748 women aged 20–24 years for whom there was complete information on the essential variables. Table 1 shows the weighted samples for each country.

Table 1. Description of surveys and study sample of women aged 20–24 years (N=14,748)

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was child marriage, defined by the United Nations as marriage involving a person under the age of 18 (United Nations, 2014). This was obtained by asking respondents their marital status and their age at first marriage. A dichotomous variable was created and grouped by whether a respondent married as a child (<18 years) or otherwise. In this study, girl-child marriage is used because of the focus on girls as the study sample.

Explanatory variable

The independent variable was FGM, derived by asking respondents if their genital area ‘was nicked with nothing removed’, ‘had something removed’ or ‘was sewn shut’. The responses were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’, coded No=0, and Yes=1.

Covariates

Eight covariates were considered in the study. These were broadly grouped into individual- and community-level variables. The individual-level variables included age, educational level, employment status, wealth quintile and exposure to mass media. Age was categorized as 20, 21, 22, 23 and 24 years. Educational level was grouped into no education, primary and secondary/higher. Employment status was categorized as not working and working. In the DHS, wealth quintile is computed based on household assets and characteristics of the household using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and grouped into poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest. Exposure to media was derived from questions asked on frequency of listening to the radio, reading newspapers, watching television and access to the internet. Respondents who never listened to the radio, read newspapers or watched television and who had no access to the internet were considered as those with no exposure to mass media, and otherwise as those exposed to mass media (Fatema & Lariscy, Reference Fatema and Lariscy2020). Residence, community literacy level (proportion of women who can read and write) and community socioeconomic status (proportion of women in the richest household quintile) were considered as contextual-level factors. Residence was coded as ‘urban’ or ‘rural’. Community literacy level and community socioeconomic status were each coded as ‘low’, ‘middle’ and ‘high’. These were generated as the percentage of community members in the sampling cluster that were in the richest quintile and high literacy level aggregated at the national level using PCA. Details of how these were generated have been published in a previous study (Solanke et al., Reference Solanke, Oyinlola, Oyeleye and Ilesanmi2019). The selection of variables was in line with their theoretical significance and practical importance for girl-child marriage (Hotchkiss et al., Reference Hotchkiss, Godha, Gage and Cappa2016; Bezie & Addisu, Reference Bezie and Addisu2019; Efevbera et al., Reference Efevbera, Bhabha, Farmer and Fink2019).

Data analyses

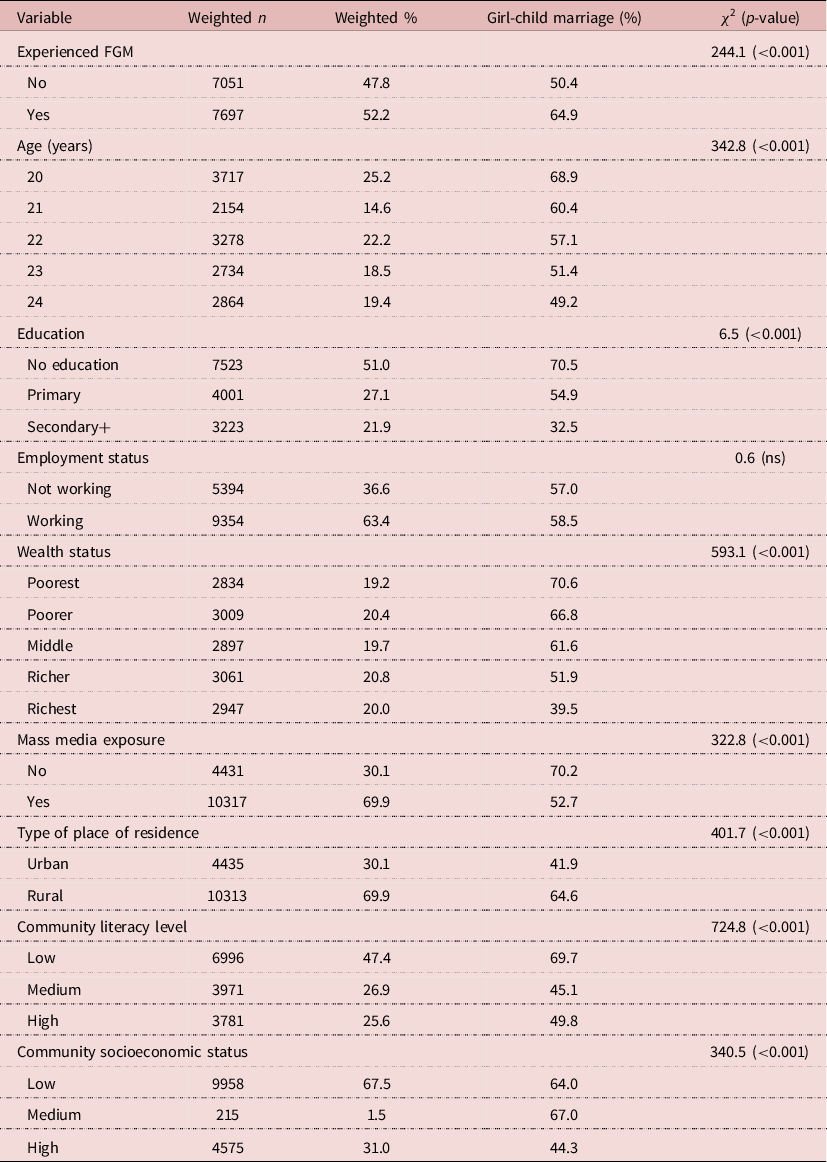

The study followed four steps to analyse the data using Stata version 14.0. First, the prevalences of girl-child marriage and FGM in sub-Saharan Africa were computed using frequencies and percentages. Second, the distributions of girl-child marriage across FGM and the covariates were calculated. Third, the chi-squared test of independence (χ 2) was used to examine the association between girl-child marriage, FGM and the covariates, with significance set at 95% confidence interval (p<0.05) (Table 2). Statistical significant variables at the χ 2 level were further analysed using a two-level multilevel logistic regression. As per the two-level modelling used in this study, women were nested within clusters to account for the variance in Primary Sampling Units (PSUs). Clusters were regarded as random effect to take care of the unexplained variability at the contextual level (Solanke et al., Reference Solanke, Oyinlola, Oyeleye and Ilesanmi2019). Prior to the multilevel logistic regression analysis, a multicollinearity test was conducted among all variables that were significant at the χ 2 test using variance inflation factor (VIF). There was no indication of multicollinearity (Mean VIF=1.57, Maximum VIF=2.32, Minimum VIF=1.01).

Table 2. Distribution of girl-child marriage among young women by FGM status and socio-demographic characteristics (N=14,748)

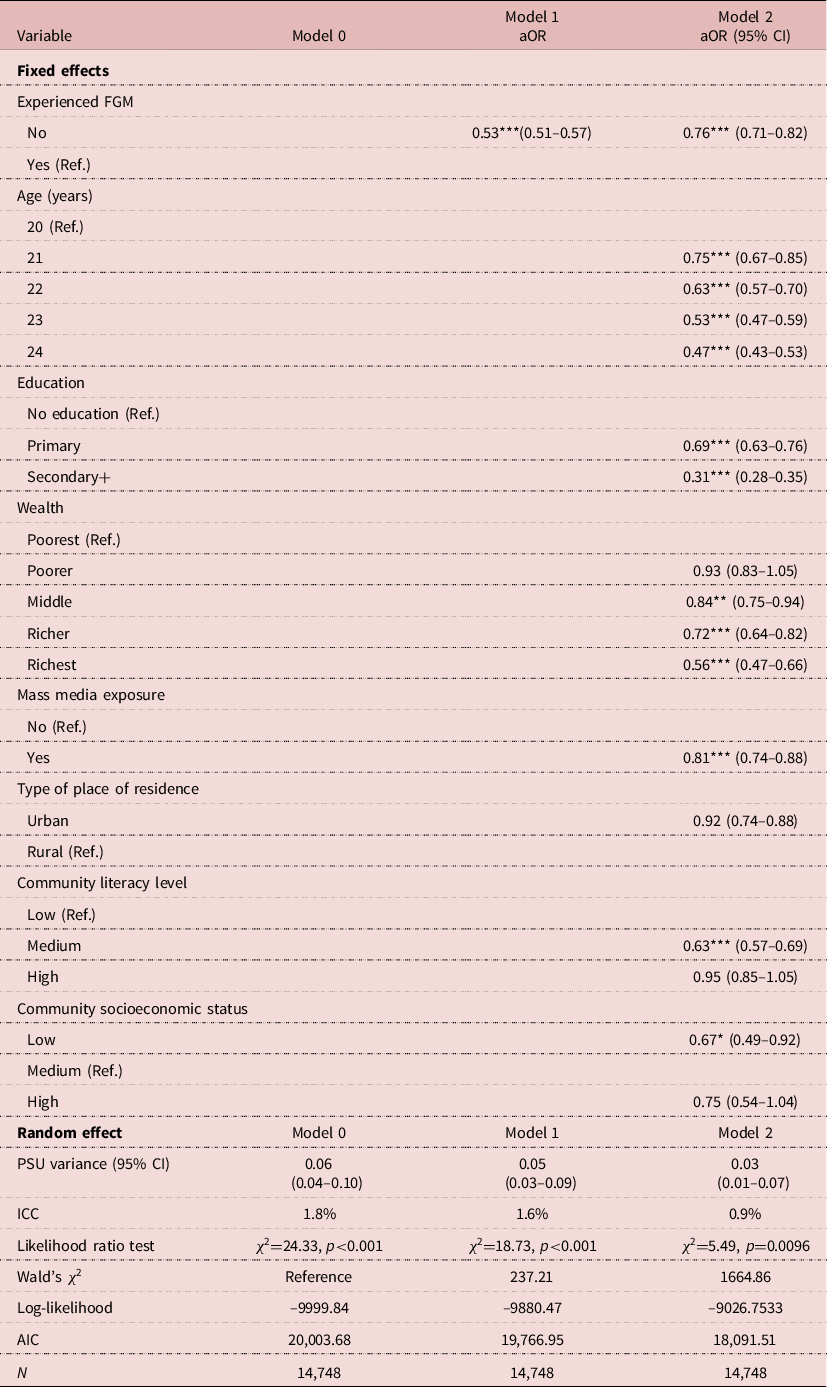

Three models were fitted, with Model 0 showing the variance in the outcome variable attributed to the clusters in the absence of the explanatory variable and covariates. The second model (Model 1) had only FGM and the final model (Model 2) was the complete model that had FGM, the individual-level and contextual-level factors simultaneously. For model 1 and model 2, crude odds ratios (cORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. To compare models, Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) test was used (see Table 3). Sample weight (v005/1,000,000) was applied to correct for over- and under-sampling, while the svy command was used to account for the complex survey design and generalizability of the findings.

Table 3. Results of multilevel logistic regression analysis of the association between FGM and child marriage among young women (N=14,748)

Ref.=Reference category; aOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio; PSU=Primary Sampling Unit; ICC=Intra-Class Correlation; AIC=Akaike’s Information Criterion.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Results

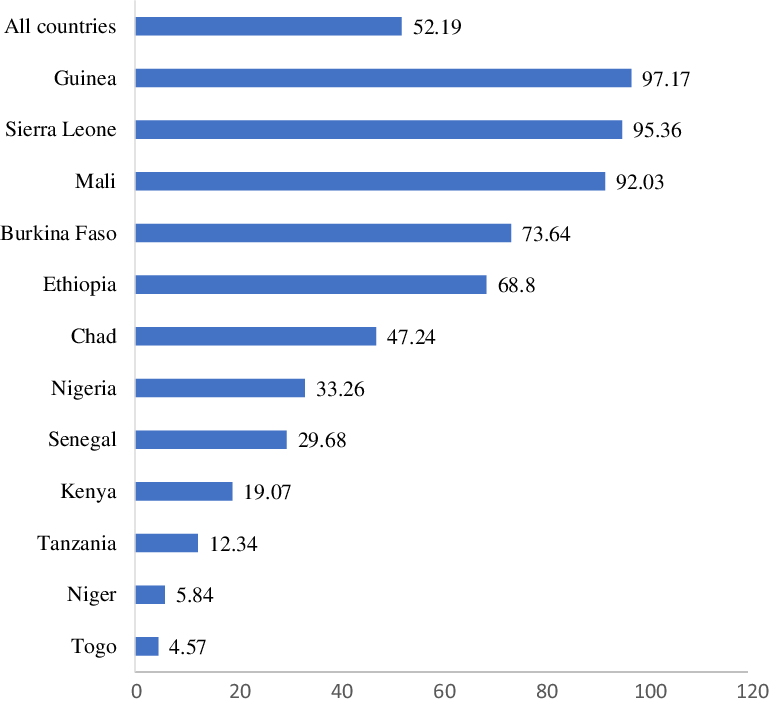

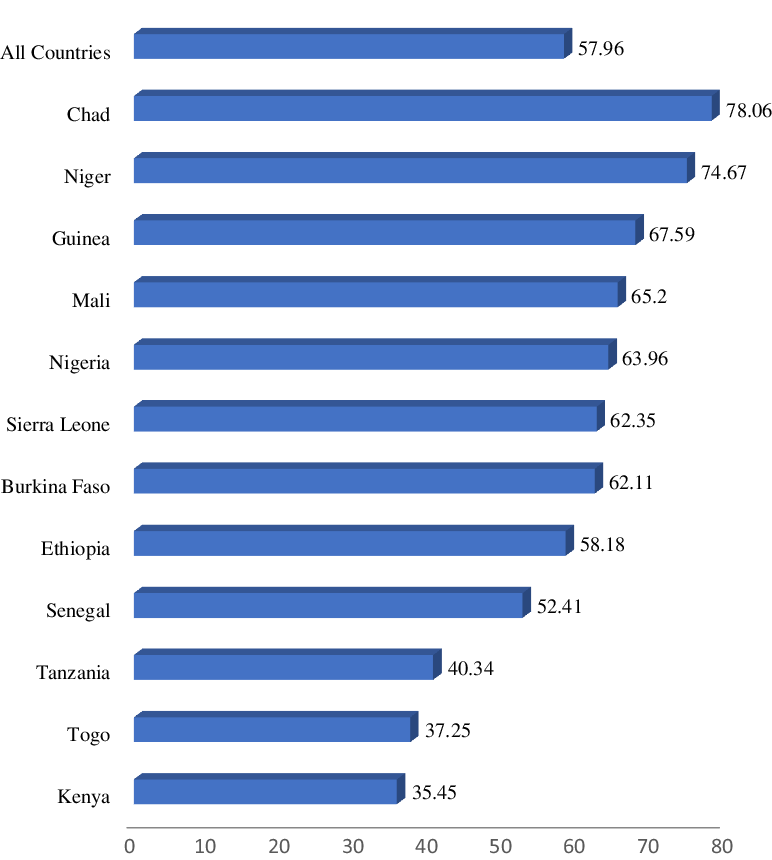

The prevalence of FGM in the twelve countries was 52.19%, with the highest prevalence in Guinea (97.17%) and the lowest in Togo (4.57%) (Figure 1). The overall prevalence of girl-child marriage in the twelve countries was 57.96%, with the highest and lowest prevalences in Chad (78.06%) and Kenya (35.45%), respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Prevalence (%) of FGM in twelve countries of sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 2. Prevalence (%) of girl-child marriage in twelve countries of sub-Saharan Africa.

Distribution of girl-child marriage by FGM and women’s socio-demographic characteristics

Table 2 shows the distribution of girl-child marriage by FGM and socio-demographic characteristics of the sample women. More than 50% of the women had experienced FGM. Out of the total sample, 25.2% were aged 20 and 51% had no formal education. Approximately 63% of the young women had an occupation, 20.8% were in richer wealth quintile households and 69.9% had exposure to mass media. In addition, 69.9% lived in rural areas, 47.4% in communities with low literacy levels and 67.5% in communities with low socioeconomic status. Results of the χ 2 test indicated that all the explanatory variables had significant associations with girl-child marriage, except employment status.

Measures of association

Table 3 shows the results of the multilevel regression analysis of the relationship between FGM and girl-child marriage among the sample women. The complete model (Model 2) presents results of the relationship between FGM and girl-child marriage, after controlling for the effect of both individual- and community-level factors. The results indicate that women who had never experienced FGM were less likely to experience girl-child marriage (aOR=0.76, CI=0.71–0.82) compared with those who had experienced FGM.

In terms of the individual-level factors, the odds of girl-child marriage were lower among women aged 24 years at the time of the survey compared with those aged 20 years (aOR=0.47, CI=0.43–0.52). Also, women with secondary education were less likely to experience girl-child marriage compared with those with no formal education (aOR=0.31, CI=0.28–0.35). The odds of girl-child marriage reduced with increasing wealth quintile, with women belonging to the richest wealth quintile less likely to experience girl-child marriage compared with those of the poorest wealth quintile (aOR=0.56, CI=0.47–0.66). Furthermore, the odds of girl-child marriage were lower among women who had exposure to mass media compared with those who were not exposed to mass media (aOR=0.81, CI=0.74–0.88). Of the community-level factors, a lower odds of girl-child marriage was found among women who lived in communities with medium literacy level compared with those in communities with low literacy level (aOR=0.63, CI=0.57–0.69), and those who lived in communities with low socioeconomic status compared with those in communities of medium socioeconomic status (aOR=0.67, CI=0.49–0.92).

Discussion

This study investigated the association between FGM and girl-child marriage in sub-Saharan Africa. It was conducted with the intent of providing evidence of the persistence and shifts in both practices that might trigger transformative actions to enhance the elimination of the acts. Overall, the findings revealed a greater than average prevalence of both FGM (52.19%) and girl-child marriage (57.96%) in sub-Saharan Africa, with the highest prevalence in Guinea for FGM (9 in 10 persons) and Chad for girl-child marriage (8 in 10 persons). These findings are in pursuant with a study conducted in Tanzania, which concluded that the prevalences of FGM and girl-child marriage were high in the country and that the rate was similar to that of the current study (Avalos et al., Reference Avalos, Farrell, Stellato and Werner2015). A study conducted in Guinea also showed a similar results (Van Rossem & Gage, Reference Van Rossem and Gage2009). Similarly, a study on girl-child marriage in 22 sub-Saharan African countries also indicated that Chad has a high prevalence of girl-child marriage (77.90%) (Yaya et al., Reference Yaya, Odusina and Bishwajit2019). Although recent situational reports (UNICEF, 2013, 2016) have noted declines in both FGM and girl-child marriage in sub-Saharan Africa, the overall prevalence noted in this study is worrisome, especially for Guinea and Chad. This could be driven by deeply rooted socio-cultural norms and social pressures, which facilitate these harmful practices through enforcement or even manipulation (Ohchr et al., Reference Ohchr, Undp and Unesco2008). Educational interventions (e.g. advocacy campaigns) and law enforcement could help minimize these harmful practices.

In this study, women who did not experience FGM were less likely to experience girl-child marriage compared with their counterparts who did experience FGM. Girl-child marriage has been found to be linked to FGM in previous studies (Sakeah et al., Reference Sakeah, Debpuur, Oduro, Welaga, Aborigo, Sakeah and Moyer2018; Karumbi & Gathara, Reference Karumbi and Gathara2020). This supports the view that FGM is a major corridor to girl-child marriage among women in Africa (Karumbi & Gathara, Reference Karumbi and Gathara2020). Besides, a commonly held assumption in sub-Saharan Africa is that a woman who is circumcised is less likely to be promiscuous compared with other leading outcomes associated with the FGM practice (Varol et al., Reference Varol, Fraser, Ng, Jaldesa and Hall2014). It could be that the purpose of girl-child marriage and FGM is to help preserve virginity and control girls’ sexuality for marriage (Karumbi & Gathara, Reference Karumbi and Gathara2020).

Previous studies on the individual-level factors influencing girl-child marriage have found age of the respondent, educational attainment, wealth quintile and media exposure to be major socio-demographic factors (Sekine & Hodgkin, Reference Sekine and Hodgkin2017; Rumble et al., Reference Rumble, Peterman, Irdiana, Triyana and Minnick2018; Okiyi et al., Reference Okiyi, Odionye and Okeya2020). The present study found that women aged 21–24 years at the time of the survey were less likely be married before the age of 18 years than those aged 20 years. Respondents with a higher educational level, those in the higher wealth quintile and those with media exposure were less likely to experience girl-child marriage. Girls who marry early (i.e. before or at the age of 18) will not have completed their secondary education, and hence they are more likely to drop out of school. More highly educated girls are more likely to marry later than less educated girls. Previous studies in Asia (e.g. Singh & Vennam, Reference Singh and Vennam2016) and Ethiopia (e.g. Erulkar et al., Reference Erulkar, Ferede, Ambelu, Girma, Amdemikael and GebreMedhin2010; Presler-Marshall et al., Reference Presler-Marshall, Lyytikainen and Jones2016) found education to be positively related to greater decision-making among girls (Boyden et al., Reference Boyden, Pankhurst and Tafere2013). Education facilitates the empowerment of girls and women, making them more aware of their rights, which might delay marriage (Karumbi & Gathara, Reference Karumbi and Gathara2020).

Women living in communities with medium literacy levels were less likely to experience girl-child marriage, as were those living in low socioeconomic status communities. Community women’s literacy level often predicts women’s susceptibility to early marriage, and economically autonomous women have a greater tendency not to consent to girl-child marriage (Paul, Reference Paul2019). Community literacy level is thus a major driver of women’s autonomy and empowerment (Duflo, Reference Duflo2012). Unlike the findings of previous studies indicating that women living in lower socioeconomic status communities are more likely to experience girl-child marriage (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Edmeades, Kes, Petroni, Sexton and Wodon2015; Hotchkiss et al., Reference Hotchkiss, Godha, Gage and Cappa2016), the current study found that women residing in communities with medium socioeconomic status were more likely to experience girl-child marriage. Methodological and context-specific variations could account for these inconsistent results. Future research could examine trends over time to provide a better understanding based on context-variations associated with girl-child marriage taking into account other socio-cultural determinants.

The main strength of this study lies in its use of nationally representative data and its rigorous analysis. The large sample size also allowed generalization of the findings to the entire population of the countries included in this study. However, the study used cross-sectional survey data, which limits the ability to make causal inferences from the findings. Also, social desirability bias may have resulted in under- or over-reporting on sensitive issues such as FGM and girl-child marriage.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated a significant relationship between FGM and girl-child marriage with educational attainment, mass media exposure and community literacy level in sub-Sahara Africa. Tackling these factors could help eliminate girl-child marriage and FGM. Interventions should focus on girls’ socio-demographic needs, community socioeconomic level, sexual and reproductive health service provision, and information campaigns against FGM. Policies to eliminate these practices should focus on compulsory basic education, poverty alleviation and increased access to mass media. Further campaigns should cover more of communities with lower literacy level and medium socioeconomic status. These steps will not only help stop girl-child marriage but also help reduce early pregnancies, maternal and child morbidity as well as mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the MEASURE DHS project for granting free access to their original data. The dataset is freely available for download on https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm

Author contributions

BOA conceived the study, performed the analysis and wrote up the data and methods. BOA, JEH, AS, OAB, EB, CA and TS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised and proof-read the manuscript for its scholarly content and gave consent for the final version to be published.

Funding

The authors sincerely thank Bielefeld University, Germany, for providing financial support through the Open Access Publication Fund for the article processing charge.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. There are no financial, copyright, trademarks or patent implications arising from this research and no organization has any vested interest in this research.

Ethical Approval

This study used data from DHS datasets, which are publicly available. ICF international and an Institutional Review Board (IRB) in each respective country approved all the DHS surveys in line with the US Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available at: http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.