Political science students struggle to grasp the complex dynamics of revolutionary moments: when mass protests threaten authoritarian governments and security forces are called into the streets. The outcomes of these events can be perplexing. Why do large and well-organized movements, such as those in Myanmar (2007–2008) and Iran (2009), sometimes fail despite developing seemingly unstoppable momentum, whereas others precipitate the rapid fall of hitherto robust regimes, such as transpired in Romania (1989), Tunisia (2011), and Egypt (2011)? Despite the growing academic literature on the topic, as well as the barrage of images and news coverage, it is still often difficult for students to understand the motivations and strategies of real-world actors in such volatile and high-risk situations—and how they interact to produce history-changing outcomes.

Traditional teaching techniques that focus on readings, lecture, and discussion do not always allow students to fully internalize the dilemmas of revolutions—from the angst of dictators, to the ambivalence of the military, to the hopes and fears of protesters. Indeed, the academic literature focuses heavily on structural factors that precede the emergence of crises or on only one or two variables that explain their outcomes—for example, the military’s tendency to defect when confronting protesters (Chenoweth and Stephan Reference Chenoweth and Stephan2011), the ways that dictatorships manipulate security forces to defend their interests through counterbalancing (De Bruin Reference De Bruin2018), and recruiting and promoting based on perceived loyalty (Roessler Reference Roessler2011). Another reason that students struggle to internalize this academic literature is the prevalence of quantitative methodologies with which they often lack familiarity.

Research shows that active-learning techniques can convey a better understanding of complex political phenomena by allowing students to experience events for themselves and “get inside the head” of important actors, albeit in a simulated form (Frederking Reference Frederking2005; Haynes Reference Haynes2015; Jiménez Reference Jiménez2015). We therefore developed a simulation on civil–military relations to expose students to the motivations and strategic calculations facing decision makers whenever authoritarian regimes find their continued rule contested in the streets. In addition to grounding students’ classroom learning in concrete experiences, our simulation helped them develop teamwork and negotiating skills.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

We designed the simulation around four key substantive learning goals that we believed students would struggle to understand from the readings alone or were drawn from works that we did not have the space to assign. First, we wanted to inculcate the importance of physical and symbolic terrains and how they shape the tactical choices of actors. Mass protests tend to congregate around large, culturally important squares, such as Paris’s Place St. Michel or Cairo’s Tahir Square. Similarly, military units tend to target symbolic buildings when they seize power, such as a presidential palace, to demonstrate strength and galvanize others to their side (Singh Reference Singh2014).

Second, we sought to emphasize the perils inherent in military deployment during revolutionary crises. The army has the discipline, firepower, and training to rapidly quell mass dissent—as evidenced in China’s suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and the USSR’s brutal crushing of the 1956 Hungarian demonstrations. Yet, when ordered to fire on protesters, rank-and-file soldiers often defect, and the military high command may even overthrow the government rather than witness the fracture of its units (Barany Reference Barany2016; Chenoweth and Stephan Reference Chenoweth and Stephan2011). Reliance on military force, in short, is a powerful and yet unreliable tool with which to suppress protests.

Third, we wanted to convey the capabilities and limitations of other security forces in a dictator’s arsenal. The regular army’s tendency to defect has led many regimes to invest in parallel forces: from riot police to praetorian guards to youth brigades to other internal security agencies, such as the Middle East’s ubiquitous mukhabaraks (Sayigh Reference Sayigh2011). Indeed, the police and intelligence services ordinarily conduct day-to-day repression in authoritarian regimes and are usually the first line of defense against protesters (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Their loyalty is ensured through personal, ideological, ethnic, and/or sectarian recruitment. Yet, their generally small size often enables mass demonstrations to grow too large, overstretching the capabilities of irregular units and plunging regimes into so-called end-game scenarios.

Finally, we wanted to stress the importance of bargaining and the difficulties of making credible commitments in the midst of revolution. The diversity of actors involved in these crises—including factions of the regime, various security units, and an often-fragmented opposition—frequently means that no single group can prevail relying solely on its own resources. Negotiation and alliances are thus necessary but bring with them risks and insecurity as the evolving situation leads actors to abandon their promises or even double-cross their partners.

Fourth, we wanted to stress the importance of bargaining and the difficulties of making credible commitments in the midst of revolution.

In addition to the substantive learning goals, the simulation provided an opportunity to develop important skills such as teamwork, diplomacy and negotiation, and strategic thinking. Being able to successfully complete group projects is a vital workforce skill. We asked students to work in small teams and provided guidance on how to divide preparation duties and write a group strategy memo. We also aimed to make negotiation central to the simulation, requiring students to communicate within their own team as well as with representatives of other teams.

Finally, we wanted to teach students to think strategically. When well designed, simulations can force participants to interact with the strategies of their allies and opponents—that is, to think “down the chessboard” while coping with dynamically changing situations (Hunzeker and Harkness Reference Hunzeker and Harkness2014).

Our challenge was to combine the development of these skills with the substantive material—that is, the importance of terrain, soldiers’ proclivity to defect, paramilitary forces’ role, and bargaining dynamics—to create an intuitively realistic, fairly complex, and yet still manageable simulation scenario and rule structure.

THE SIMULATION

We used this simulation with both master’s and upper-division undergraduate seminar students in groups ranging from nine to 21. Students were assigned teams and given a packet with the scenario and rule structure one week in advance of the simulation. Each team was also given private information about its actor, including their interests and preferences (table 1). Teams were then tasked with writing a preparatory memo that developed an initial strategy, outlined their first round of play, and developed contingency plans for possible obstacles to their strategy. We encouraged each team to develop its own internal decision-making process to function within a fast-paced simulation by designating emissaries to negotiate with other groups, intelligence personnel to track events, and scribes responsible for submitting their teams’ orders. Instructors who might be concerned about free-riding—which was not a major concern with our small teams of upper-division undergraduate and graduate students—could assign each student a specific role in their team’s decision-making structures and hold them individually responsible for corresponding sections in their group’s strategy memoranda.

Table 1 Private Information on Team Preferences

The Scenario

Our simulation begins with a popular uprising against the government of Panem, which has been ruled for decades by the iron fist of a personalist dictator. After weeks of escalation, the opposition now occupies key sites in the city; however, it is divided between pro-democracy protesters and a religious movement intent on installing a theocracy and in possession of a small underground guerrilla army. In response to the escalating crisis, the government has mobilized both its riot police and revolutionary guards—although the army still remains in its barracks. The opposition has declared that it will continue to control the streets until the government falls. The dictator, of course, is intransigent. Game play thus begins at the outset of the so-called end-game phase of anti-regime protests.

We purposefully based our scenario in a fictional world, cobbled together from various contexts as well as novels. Beyond the obvious reference to the Hunger Games trilogy, which sets up the government as a repressive regime, we developed a nomenclature for the scenario’s varying locations and actors that mixed experiences from different regions and historical cases. We used a map of Kiev for our capital city and termed the regime’s praetorian guard the “revolutionary guard” (à la Iran and Libya). Meanwhile, the non-democratic opposition’s goal to install a theocratically oriented monarchy harkens back to certain nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century European movements (e.g., the Spanish Carlists and French Legitimists). Students were further encouraged to develop their own identity for their team and to act “in character” during the simulation.

Our mobilization of such a diversified symbolic lexicon served important pedagogical purposes. Students possess varying degrees of knowledge about current events, different geographical regions, and historical revolutions. They also have embedded assumptions about how politics functions in differing places and times. We were concerned that if students identified the simulation with a particular real-world event, they would tailor their actions to reflect what actually happened or to their preconceived prejudices. Therefore, to encourage students to set aside their assumptions, to “level the playing field” in terms of prior knowledge, to be their own decision makers, and to think strategically, we decided to develop a fictional scenario.

Rule Structure

Students were divided into four teams, representing the government, the army, the pro-democracy opposition, and the religious opposition. Their objective was to occupy a majority of the centers of power within the capital city by the end of the simulation, allowing them to retain power or shape the transition to a post-revolutionary government. Power-sharing coalitions were explicitly allowed. We designated eight such power centers, divided into government installations (i.e., the Presidential Palace, National Assembly, Ministry of Defense, Intelligence Headquarters, and Broadcasting Station) and central gathering sites (i.e., the Public Square, Public Park, and Cathedral Square).

Students were divided into four teams, representing the government, the army, the pro-democracy opposition, and the religious opposition.

Each team had an initial number of units that were stationed at assigned points in the city. The government controlled equal numbers of riot police and revolutionary guards that were protecting the five key government installations. The army had troops stationed both at bases just outside the capital, which could move immediately into the city center on the first turn, and units in the countryside that took longer to arrive and could do so only over a vital bridge. The pro-democracy opposition began with approximately double the number of protesters as the religious opposition, which was divided between the Public Square and the Public Park. Although it was initially small, the religious opposition controlled Cathedral Square and had an armed unit of clandestine militants, which could suddenly deploy anywhere on the map when first summoned. Students were provided with a detailed map of the capital, based on Kiev, indicating the locations of the power centers (figure 1).

Figure 1 Map Excerpt

Of vital importance, although the government and military had a fixed number of units, the opposition could increase their numbers over time. For each central gathering site that an opposition team controlled at the end of a round, we rolled a die to see whether they would recruit one or two new protester units. We did not allow the religious opposition to train and equip additional units of armed guerrillas because our simulation is designed to replicate fast-paced events, measured in days rather than months.

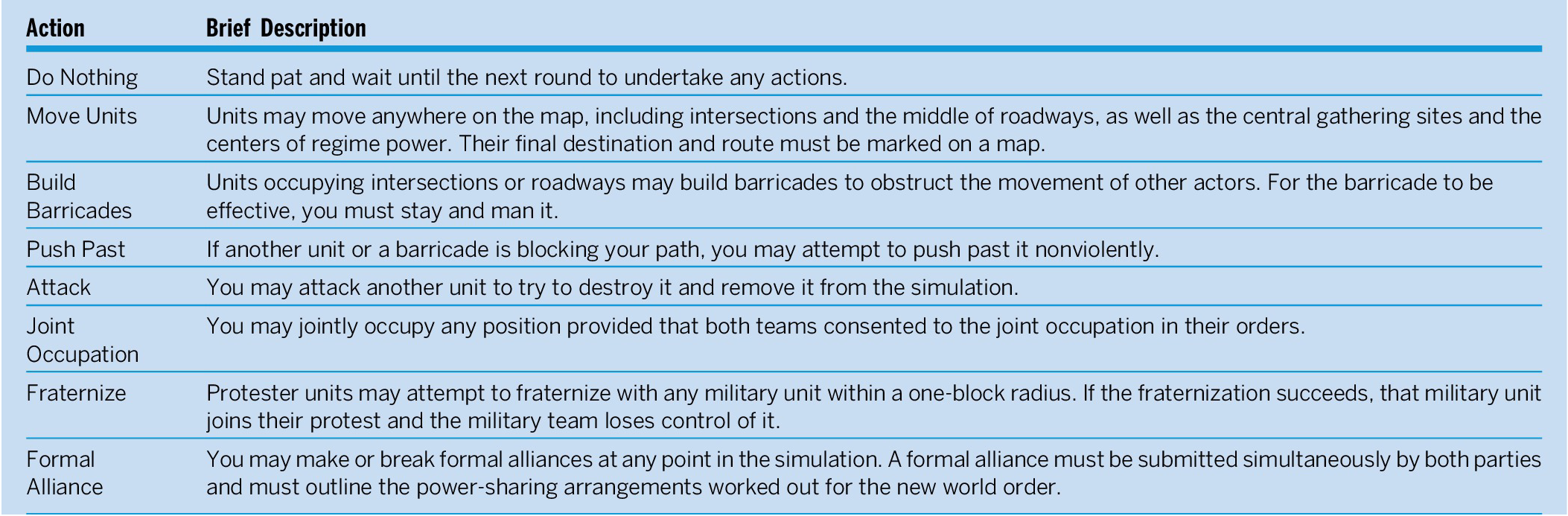

Each round of play began with a period of negotiation in which teams could coordinate their strategy and talk to other actors. They would then write a set of orders detailing the actions to be taken by each of their existing units. Because we enacted our simulation during a single two-hour seminar session, we allowed approximately 10 minutes of negotiations per round followed by a few minutes to submit orders. We provided the teams with a list of possible orders, including doing nothing, moving, building barricades, pushing past other units or barricades in their way, attacking other units, consenting to joint occupation of an area or site, fraternizing, and making or breaking formal alliances (table 2). Each unit could combine two actions per turn, and teams were given extra maps to draw the routes that their units would travel, where barricades should be constructed, and other relevant details.

Table 2 Sample Actions

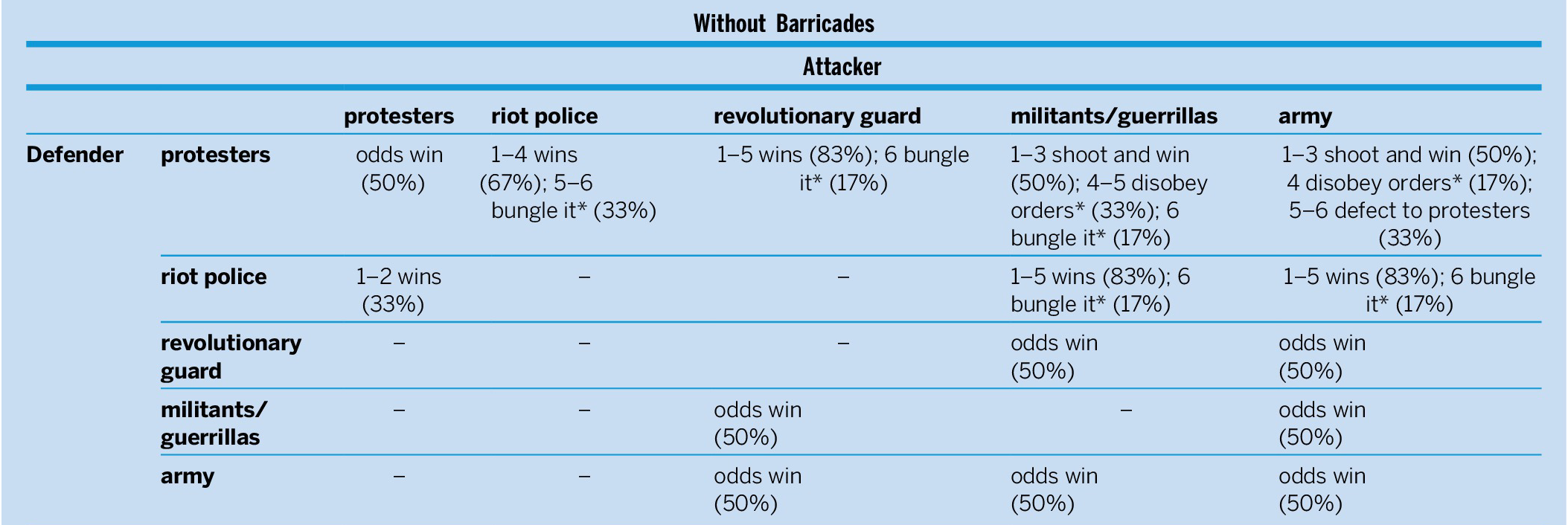

Teams were provided with tables of the odds that certain actions would be successful, depending on the type of units facing one another and their available defenses; dice were rolled to determine outcomes (table 3). For example, fraternizing protesters had a 17% chance per turn—that is, players needed to roll a six—of converting military units to their cause, in which case they gained control over an armed unit. Alternatively, attacking riot police would prevail 67% of the time when facing protesters, but those odds decreased to 17% if the protesters had built barricades. Army units attacking riot police had an 83% chance of victory, whereas revolutionary guards attacking the army had only a 50% chance of success. These are only a few examples and instructors should feel free to tailor the relative strength of different groups for the particular types of states and revolutionary situations that they want to replicate. Although we provided students with detailed probability tables, instructors can oblige students to make decisions under more realistic conditions of less complete information by providing a vaguer conception of odds (e.g., low, medium, or high).

Table 3 Resolving Actions with a Roll of the Dice

Notes: *In these cases, the unit is unsuccessful in the attack but survives to fight another day. Otherwise, failed attacking units and unsuccessful defending units are destroyed/disbanded.

When all teams had submitted orders, we resolved them sequentially beginning with the pro-democracy opposition, followed by the religious opposition, the government, and the army. We adopted this order of play (1) to simulate the fact that opposition groups often possess the initiative during mass protests (and the military often hedges); and (2) as a necessary simplification of reality, wherein competing factions usually act simultaneously. The luck of the dice determined outcomes, with the instigating team rolling. We also publicly updated the position, movement, and state of all units on a large interactive map projected at the front of the classroom.

Debriefing

Debriefing constitutes a critical component of effective simulations. Through explicit discussion of their experiences, students can analytically draw connections with course content, deepening their understanding of important theories and concepts. This also provides an opportunity for the entire class to gain a broader perspective on what happened and why by sharing their internal team deliberations and motivations (Newmann and Twigg Reference Newmann and Twigg2000; Smith and Boyer Reference Smith and Boyer1996; Wedig Reference Wedig2010). To prepare for this debriefing, we tasked students with writing individual short (i.e., 800-word) reflective essays on their experiences. We then devoted a substantial proportion of the seminar following the simulation, approximately one hour, to comprehensive debriefings.

We first asked teams, in turn, to discuss what transpired from their perspective. This facilitated a basic recap of the simulation and jogged memories. Although the teams had a week to prepare and had submitted written versions of their initial strategies, each simulation nonetheless began somewhat chaotically and with a flurry of cross-team negotiations. Indeed, most teams invariably came to realize that their initial plans were failing due to lack of cooperation by other actors. They thus had to quickly improvise to a rapidly changing situation. For example, after two hours of disappointments, backstabbing, and power grabs, our first simulation ended with a surprising negotiated pact between the government and the religious opposition. Because the two teams collectively controlled a majority of power centers, they were able to enforce their vision on society. They even had drafted and signed a new constitution that preserved the personalist dictatorship but with a more hardline theocratic stance and an expanding role for religious leaders in governance.

We also asked students to discuss the dynamics both within and among their teams. Several important points emerged during this first debriefing: for example, although the government prevailed in the end, it had felt outnumbered and insecure the whole time. This led the teams to desperately seek allies and attempt to negotiate with anyone who was willing to deal. Indeed, although the team’s initial plan was to work primarily with the army, it quickly gave up on a hedging military (which had not necessarily turned against them) and approached the religious opposition.

Second, fearing that fraternization would lead some of their units to defect and, ultimately, to army-on-army battles, the military had originally intended to side with the pro-democracy opposition. Yet, after the democratic protesters blocked the entrance of an army unit into the city on the first round, the military decided it could not be trusted and scrapped its strategy. Personality conflicts also developed between one of the pro-democracy students and the rest of the team, leading to fractured behavior and unkept promises.

Third, we prompted students to reflect on how their experiences related to the assigned readings on military behavior during revolutions. Based on the previous insights, they noted that the literature was heavily focused on structural dynamics (e.g., prior coup proofing) and neglected issues of personality, leadership, trust, and contingency. They observed that a context of high stakes, high risk, and uncertainty over other actors’ behavior (which must be magnified in a real-world crisis) led them to shape their strategies around who they thought they could trust and with whom they could work. The government team also turned first to units it knew were the most loyal—the riot police and revolutionary guards over whom we had given it complete control—and showed great hesitancy in ordering the military to repress. Constructed as an independent actor, with its own corporate interests, all teams intuitively understood that the military could not necessarily be relied on to side with the regime. We then discussed which real-world circumstances would make the military more or less independent from the regime and thus how its behavior might differ across revolutionary contexts.

CONCLUSION

This simulation enhances students’ understanding of the complex dynamics of an authoritarian regime facing down mass protests, and how the military might behave in those circumstances. Although we have incorporated the simulation into classes on both civil–military relations and contentious politics, it can also be used to explore the broader dynamics of civil resistance, revolutions, and democratization—or narrowed and contextualized to delve into specific historical moments. The simulation can also be expanded to accommodate larger classes by adding additional teams, such as paramilitary units and more protester groups.

This simulation enhances students’ understanding of the complex dynamics of an authoritarian regime facing down mass protests and how the military might behave in those circumstances.

Indeed, both students and colleagues have already proposed numerous ways to tailor the simulation to different pedagogical purposes. A professor of modern history who observed our simulation, for example, is adapting the rule structure—and using historic maps of Madrid and Barcelona—to simulate the chaotic early events of the Spanish Civil War. Students have suggested that we incentivize controlling the broadcasting station by allowing the possessor to recruit new units or summon reinforcements, thereby emphasizing the role and value of communication. We can imagine a host of other additions and modifications to highlight the complex and important real-world dynamics that underly every revolution.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000888.