1. Introduction

Expressions like English back to back and year after year are found in several European languages. The examples in (1)–(2) show Norwegian equivalents:

Expressions like rygg mot rygg and år etter år will be referred to as ‘NPN constructions’, or just ‘NPNs’. An NPN consists of two identical singular count nouns (N1 and N2) with a preposition (P) between them.Footnote 2 (In languages with case marking on nouns, the nouns may have different cases.) An NPN typically consists of nothing more. The nouns are bare singular count nouns – ‘bare singulars’ for short. The notion of ‘bare singular’ is compatible with the presence of modifiers, but NPNs typically have none (except that the PN sequence will be analysed here as a modifier of N1). In English, modifying adjectives are found, as in (rainy) day after rainy day, for example, which is very uncommon in Norwegian. We will look at two other modifier types. The first type is PPs in NPNs with measure nouns, headed by med ‘with’ or av ‘of’ whose complement designates the measured mass, as in (3):Footnote 3

Such PPs are constituents of the NP headed by N2, and will therefore be called internal modifiers. Semantically, they modify both nouns, a property that makes these NPNs resemble coordinate structures (see Sections 2.2 and 4.4 below).

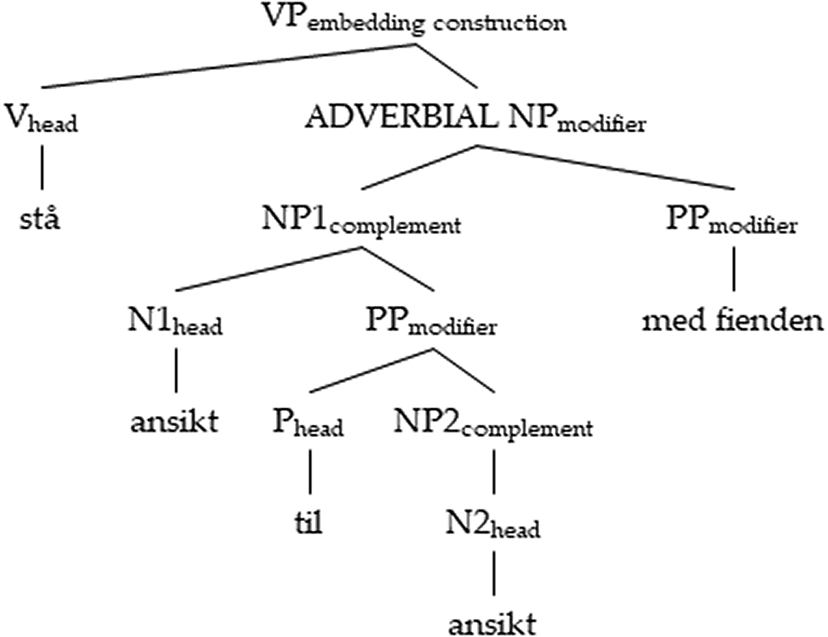

A different kind of PP modifier is illustrated in (4)

:The phrase headed by med modifies not the nouns (ansikt med Vespasian og Titus ‘face with Vespasian and Titus’ makes no sense), but the whole NPN meaning. Such modifiers will be called external, and I discuss them briefly in Section 5.2 below.

Identical nouns (except for case) are by definition a necessary property of NPNs.Footnote 4 Non-NPN variants with different nouns are often hardly acceptable, such as *?day after night as a variant of day after day. Footnote 5 However, an NPN like hand in hand may be changed into non-NPN paw in hand, for example. Some such non-NPNs are unremarkable; compare man against man and man against animal. The difference in acceptability between *?day after night and paw in hand will be shown to follow from semantic structure and to correlate with differences in syntactic function.

NPNs are typically used in various adverbial functions, like rygg mot rygg in (1).Footnote 6 But in several Germanic languages, at least, certain kinds of NPNs are also used in nominal (argument) functions, like the subject in (2) and the object in (3). Kinn (Reference Kinn2021a) finds that adverbial and other modifying functions (e.g. modifiers of nouns) account for about 80 % of the NPN tokens in Norwegian Bokmål, while 20 % are nominal.Footnote 7

In parts of the research literature, NPNs are regarded as highly idiosyncratic and problematic to analyse. This has to do with the untypical use of bare singulars, the identity of the nouns, and the relation between two singular nouns and potentially many instances of the nominal type (e.g. several days in the case of day after day).

The most influential contribution to the research on NPNs has so far been Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008). Jackendoff discusses a number of properties of English NPNs and argues that they constitute an entrenched structure violating standard principles of phrase structure – a ‘syntactic nut’ in the sense of Culicover (Reference Culicover1999).

The present contribution aims to show that NPNs are more regular than typically assumed, inheriting a number of formal and semantic properties from more schematic constructions. They also have clear compositional properties, central parts of their meanings being predictable from the components and their manner of combination. Most properties of NPNs are properties of bare singulars, prepositions, prepositional phrases, and noun phrases in general.

However, NPNs do have idiosyncratic properties, especially adverbial use of NPs (exocentricity), emergent constructional meanings, and lexicalization of some expressions. Without irregular and noncompositional properties, NPNs would not have been so easily identifiable as a construction worthy of special attention. It is the aim of the present article to highlight regular and compositional aspects, and to contribute to a better understanding of certain idiosyncrasies.

The evidence here is mostly from Norwegian, but it is compared to English examples. Some Icelandic data is adduced because that language as opposed to Norwegian has case-inflected nouns. The present study draws on the corpus study of Kinn (Reference Kinn2021a). That work on Bokmål Norwegian NPNs builds on materials of 9,241 NPN tokens from the Lexicographic Corpus of Norwegian Bokmål (Knudsen & Fjeld Reference Knudsen and Fjeld2013).Footnote 8 Most Norwegian NPNs involve one of eight prepositions (seven of which are discussed here),Footnote 9 but the corpus study also documents NPNs with several less frequent prepositions.

Borthen’s (Reference Borthen2003) work on bare singulars is a central source of inspiration. My theoretical approach draws most clearly on that of Cognitive Grammar (Langacker Reference Langacker1987, Reference Langacker1991) but is broadly compatible with constructional approaches to grammar in general (see the contributions in Hoffmann & Trousdale (Reference Hoffmann and Trousdale2013).Footnote 10 A semantic analysis in terms of construal (rather than truth conditions) is at the core of the approach. This is an important point, and I emphasize that terms like asymmetric, reciprocal, and transitive refer to conceptual semantics here and must be understood in that context. Asymmetry is by definition a property of prepositional relations, relating a trajector and a landmark. A relation R is reciprocal if R(a, b) means also that R(b, a). A relation R is transitive if R(a, b) & R(b, c) means also that R(a, c).

Section 2 reviews the research on NPNs and expands on the objectives of the present work. An important question for the analysis of NPNs has to do with the properties of bare singulars, and this is addressed in Section 3. On that background, Sections 4 and 5 deal with the internal semantic structures and external connections of NPNs. Section 6 concludes the article.

2. Research background and present objectives

Studies that (exclusively or partly) deal with properties of NPNs (and/or PNPNs)Footnote 11 include Pi (Reference Pi and Koskinen1995), Postma (Reference Postma1995), Travis (Reference Travis, Kim and Strauss2001, Reference Travis, Burelle and Somesfalean2003), Lindquist & Levin (Reference Lindquist, Levin, Römer and Schulze2003), Matsuyama (Reference Matsuyama2004), Beck & von Stechow (Reference Beck, von Stechow, Evert and Endriss2005, Reference Beck and von Stechow2007), Poss/Poß (Reference Poss [Poß]2007, Reference Poß2010), Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008), Boberg (Reference Boberg2009), König & Moyse-Faurie (Reference König, Moyse-Faurie, Helmbrecht, Nishina, Shin, Skopeteas and Verhoeven2009), Roch, Keßelmeier & Müller (Reference Roch, Keßelmeier, Müller, Pinkal, Rehbein, im Walde and Storrer2010), Müller (Reference Müller, Engelberg, Holler and Proost2011), Pskit (Reference Pskit, Skrzypczak, Fojt and Wacewicz2012, Reference Pskit, Bondaruk and Prażmowska2015, Reference Pskit and Pskit2017), Haïk (Reference Haïk2013, Reference Haïk2018), Zwarts (Reference Zwarts2013), Magri, Purnelle & Legallois (Reference Magri, Purnelle and Legallois2016), Ziem (Reference Ziem and Steyer2018), Beck (Reference Beck, Hofherr and Doetjes2021), and Kinn (Reference Kinn2021a, Reference Kinn, Neteland and Kinnb). In the following subsections, some aspects of this research literature will be reviewed and discussed in order to prepare the ground for a new analysis.

These works look at (P)NPNs in English, Dutch, German, French, Spanish, and Polish – three branches of the Indo-European languages. I have no information about NPNs in other languages.Footnote 12 It is generally difficult to find treatments of these constructions, even for the well-described Scandinavian languages. For Norwegian, all I have found is a brief paragraph in Faarlund, Lie & Vannebo (Reference Faarlund, Lie and Vannebo1997: 456) and dictionary entries.

2.1 Bare singulars and NPN structure and constituent-hood

Some researchers have proposed fairly regular phrase structure analyses of NPNs. Thus, Travis (Reference Travis, Kim and Strauss2001, Reference Travis, Burelle and Somesfalean2003) proposes analyses in terms of X-bar theory, and Haïk (Reference Haïk2013) uses similar phrase structures – although she takes the bareness of the nouns to be evidence that NPNs are morphological rather than syntactic structures. Poß (Reference Poß2010: 50) presents an analysis in Sign-Based Construction Grammar where NPNs are a kind of NPs with ternary branching and the PN sequence does not form a constituent.

Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008) does not state it explicitly, but an important reason for him to regard NPNs as idiosyncratic appears to be the use of bare singulars. An idea that is prevalent in some approaches to syntax (dating back at least to Longobardi Reference Longobardi1994) is that bare singulars are normally not able to function as arguments (in languages that have articles).Footnote 13 This accounts, for example, for the observation that sentences like Anne threw the ball and Anne threw a ball are grammatical, but *Anne threw ball is not (in most contexts).

Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008) seems to assume that the restriction on bare singulars holds for NPNs. This has far-reaching implications for his understanding of the constructions. First, it is unclear whether he regards N2 as the complement of P: ‘What follows the preposition is not a normal prepositional object, since … it cannot have a determiner’ (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff2008: 19). Jackendoff does not once refer to the PN sequence as a PP or to N2 as the object/complement of P. In his constructional representation of NPNs (on page 26), no PP is identified in syntax. P and N2 are shown as sister constituents of an NP (headed by P); see further Section 2.2 below. While Jackendoff does not explicitly deny that N2 may be some kind of complement of P, there is also no clear indication that he adopts such a view.

Second, N1 is seen as unable to head arguments (e.g. in NPNs such as those in (2) and (3) above), hence is not the head of NPN. When considering and rejecting the possibility that a nominal NPN is headed by N1, Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008: 20–21) says that ‘it is quite a peculiar NP: notice again that the noun must lack a determiner … I would suggest that if there is any head at all in N after N, it is the preposition … it is an NP headed by P’.

Research on several article languages, including English (e.g. Stvan Reference Stvan, Stark, Leiss and Abraham2007) and Norwegian (Borthen Reference Borthen2003), has documented several constructions where bare singulars do occur in argument positions. Bare singulars tend to have different referential properties from count singulars with indefinite articles (e.g. ball vs. a ball), and the conditions for their use are partly semantic rather than syntactic (see Section 3) and certainly in part language specific.

It will be argued in Section 3 that the basic structure of NPN has N1 as the head of an NP. The sequence of P and N2 is a PP modifying N1. N2 is the head of an NP complement in that PP. Adverbial NPNs have an extra semantic layer turning the basic NPN structure into an exocentric construction (see further Section 5.2 below).

An NPN is one constituent in an embedding construction, often verb-headed (verb phrase, clause, or sentence). This can be demonstrated with reliable tests for constituent-hood, viz., substitution and topicalization (see Müller Reference Müller, Engelberg, Holler and Proost2011 on German NPNs). Adverbial NPNs like rygg mot rygg ‘back to back’ in (1) above can be replaced with a single adverb like slik ‘thus’, and nominal NPNs like år etter år ‘year after year’ in (2) above can be replaced with a single pronoun like de ‘they’. Further, since Norwegian V2 syntax normally allows only one topicalized constituent in front of the finite verb, (5) and (6), which are reformulations of (1) and (2), also demonstrate the constituent-hood of the NPNs:

These properties argue against an analysis of NPNs as small clauses (as proposed by Haïk (Reference Haïk2013) for some NPNs, see Section 2.2). Whether one adopts the concept of small clauses or not (see Saurenbach Reference Saurenbach2008 for discussion), putative small clauses with PPs (e.g. him beneath contempt in English Mary considers him beneath contempt) can neither be replaced with one pro-word nor be topicalized. Thus, while NPNs can be shown with basic syntactic tests to be constituents, the opposite holds for small clauses.

The PP of NPNs bears a predicate relation to N1. This is similar to the relation of the PP to the preceding nominal constituent in a small clause (e.g. of beneath contempt to him in the example). However, this similarity is not an argument for small clause status, because such a predicate relation is a property of PP modifiers in NPs in general, for example, the books on the table, a woman with a hat, etc.

2.2 Number properties of NPNs and the role of the preposition

NPNs exhibit complex number properties. In hand in hand, the two singular nouns may correspond to two or more actual hands (The couple(s) walked hand in hand). In an NPN like guest after guest, the nouns presumably always correspond to at least three guests. Such NPNs have a plural-like semantics. Nominally functioning NPNs are singular in terms of clause-internal agreement properties in English: Guest after guest was leaving the party (see also Section 3.3 on Icelandic). But they may be antecedents of plural pronouns, as in the possible continuation They didn’t like the music.

The plural-like meaning of NPNs often goes together with a plurality of events; the guest example means something like ‘One guest left the party, then another guest left, then another, etc.’ These phenomena are not in focus here, but see Beck & von Stechow (Reference Beck and von Stechow2007), Zwarts (Reference Zwarts2013), and Beck (Reference Beck, Hofherr and Doetjes2021).

Several researchers (e.g. Postma Reference Postma1995; Travis Reference Travis, Kim and Strauss2001, Reference Travis, Burelle and Somesfalean2003; (partly) Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff2008; Müller Reference Müller, Engelberg, Holler and Proost2011; Haïk Reference Haïk2013) have assumed that NPNs involve reduplication, where N1 is a copy of N2 in syntax. This implies that there is in a sense only one singular noun in syntax, creating a mismatch with semantics since all NPNs involve at least two instances of one nominal type.

In Travis (Reference Travis, Kim and Strauss2001, Reference Travis, Burelle and Somesfalean2003), P is analysed as a quantifier with reduplicative power; it takes N2 as its complement and makes a copy (N1) which becomes its specifier. This quantifier is the head of the NPN and is responsible for the reduplicated noun corresponding to two or more instances of the nominal type.

Haïk (Reference Haïk2013) distinguishes between two kinds of English NPNs. Those that cannot function nominally are analysed as lexical small clauses (recall Section 2.1 above) headed by P, regarded as a preposition. However, a preposition normally relates the meaning of the complement (landmark) to a meaning element (trajector) expressed outside of the PP. That appears not to be the case on Haïk’s analysis.

NPNs which can function nominally (in English: those with after or (up)on) are analysed by Haïk as lexical coordinate structures headed by a reduplicated noun. P is regarded as a coordinator and causes the one singular noun in syntax to correspond to a plurality in semantics. One reason for this analysis is that these NPNs behave in some ways like coordinate constructions. For instance, in an expression like layer upon layer of clothes, the PP of clothes connects equally to both nouns (at least in semantics). As is known, this is a characteristic of coordinated constituents (a figurine and a bracelet of gold – both the figurine and the bracelet may be understood to be golden) and not of structures where a PP modifies a noun (a figurine [with a bracelet [of gold]] – only the bracelet is said to be golden).Footnote 14

In Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008), it is unclear whether N2 is seen as the complement of P (see Section 2.1). Further, on page 26, he preferentially regards N1 as a reduplicated copy of N2. The one-to-many relationship between noun and referents is stipulated there as follows:Footnote 15

As indicated by the subscript letters in this representation, one syntactic nominal entity corresponds to many semantic ones and two phonological ones (Wd = word). The P in syntax corresponds to nothing in semantics. Normally, a preposition takes a complement in syntax and relates two participants in semantics. Such a valency is not apparent in Jackendoff’s representation.

The prepositions of NPNs are formally identical to prepositions found elsewhere, and their meanings in NPNs are found also in other constructions (see Section 4 below). Consider day after day: Part of the meaning is that one day is after another day. Similarly, hand in hand is used about situations where one hand is in contact with and partly enclosed in another hand (see Poß Reference Poß2010: 75). In short, the preposition semantically connects N1 and N2 in the usual manner of a preposition.

2.3 NPN subtypes and external connections

NPNs can be subclassified in different ways based on syntactic or semantic properties. The relations between internal NPN semantics and adverbial vs. nominal function have thus far scarcely been explored in the literature, but such relations will be shown to be quite central to an understanding of the constructions.

Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008) notes that some subtypes of English NPNs (N after N and N (up)on N) can function nominally, while others cannot. This appears to underlie Haïk’s (Reference Haïk2013) distinction between lexical coordinate NPNs (with after or (up)on) and lexical small-clause NPNs (the rest). Primarily interested in NPNs with reciprocal meanings such as hand in hand and face to face, König & Moyse-Faurie (Reference König, Moyse-Faurie, Helmbrecht, Nishina, Shin, Skopeteas and Verhoeven2009) distinguish between those and others in English. Nonreciprocal NPNs include at least the potentially nominal N after N and N (up)on N. For König & Moyse-Faurie, the dichotomy reflects their interest in reciprocity, but it is important in the subclassification of NPNs. (See also Beck & von Stechow (Reference Beck, von Stechow, Evert and Endriss2005, Reference Beck and von Stechow2007).)

Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008: 17) presents a subclassification of English NPNs in the form of an inheritance hierarchy based on the individual prepositions involved. Apart from a ragbag class, he has five major subtypes, each coupled with one preposition and one or more constructional meanings: N by N (succession), N for N (matching/exchange), N after N (succession), N (up)on N (succession; large quantity), and N to N (juxtaposition; succession; transition; comparison). He concludes (on page 16) that NPNs have no predictable common meaning. He does recognize (page 18) pairing (related to reciprocity and twin NPNs, see Sections 4.5 and 4.6 below) and multiplicity, involved in succession (related to transitivity and chain NPNs, see Sections 4.3 and 4.4 below), but he does not complete any higher-level grouping on this basis, nor does he tie semantics to syntax. A similar classification to Jackendoff’s is found in Poß (Reference Poß2010: 50), and Roch et al. (Reference Roch, Keßelmeier, Müller, Pinkal, Rehbein, im Walde and Storrer2010) build explicitly on Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff2008). To sum up, Jackendoff’s subclassification is of a splitting kind, while certain other researchers propose larger subtypes.

Nominal NPNs are assigned a semantic role by the governing verb or preposition, but (case-less) adverbial NPNs have no overt expression of the semantic role of the NPN in an embedding construction (usually verb-headed). Adverbial NPNs will be shown to be adverbial NPs; compare I have said it time after time and I have said it many times. Adverbial NPs are not a widespread phenomenon in English or Norwegian, and NPNs may be the only productive adverbial NP type in these languages, covering a larger spectrum of semantic roles than other adverbial NPs. For instance, adverbial NPNs are often manner expressions, and while English does have manner adverbial NPs with way, as in You can’t do it that way (compare You can’t do it step by step), I know of no such NPs in Norwegian except for NPNs.

The semantic roles of adverbial NPNs are largely unexplored. They can most easily be analysed where an adverbial NPN can be compared to one that is the complement of a preposition (as in I waited (for) hour after hour). The PP has a similar temporal role to that of the adverbial NPN and expresses it with the preposition. These issues are complex and cannot be addressed in full depth here, but building on Kinn (Reference Kinn2021a), I will show that adverbial NPNs in Norwegian express at least manner, temporal and local roles.

2.4 Present claims and objectives

In this section, I outline the argument of the present paper.

The bare singulars of NPNs have referential properties that are typical of bare singulars in general, involving both types and instances (see Section 3.4). The meaning of a bare singular is a singular nominal type corresponding to one or more instances. The relation in number between types and instances is regular, and there is no need to assume reduplication in NPNs. The nouns in NPNs are identical simply because they are used to invoke the same nominal type.

The meanings of prepositions in NPNs are the same as in some other constructions (but not always the most typical meanings of the prepositions). They have the typical semantic valency of prepositions, relating an external trajector to an internal landmark. That cannot be said of either coordinators or quantifiers. Coordination-like and plural-like properties in NPNs can be explained without recategorization of prepositions.

The PN sequence in NPNs is a PP, inheriting properties from the general PP construction like other PPs with bare singular complements. The preposition is its head, and N2 is an ordinary complement, designating the landmark of the prepositional relation. An NPN is at the core a regular NP, inheriting properties from a general NP construction like other NPs with bare singulars. N1 is the head of the NP, and the PP is its modifier. N1 designates the trajector of the prepositional relation. Adverbial NPNs are exocentric constructions with an additional semantic layer on top of the NP itself, profiling an unspecified relation between an external trajector and a landmark designated by the nominal core of the NPN.

Prepositions involve an asymmetric construal of the relation between a pair of participants: trajector and landmark. In NPNs, there are emergent construals of the organization of nominal participants, giving ‘twin’ and ‘chain’ NPNs. In twin NPNs, there is a construed reciprocal relation that strengthens the pairwise organization of participants. In chain NPNs, the prepositional relation is not only asymmetric, but is construed as transitive (see Section 4.2 below). This motivates the emergence of a chain-like organization of instances of the nominal type involved.

The organization of nominal instances in chain NPNs explains their coordination-like properties without the need to assume coordination. It further explains why N1 and N2 normally have to be identical in these NPNs (*?day after night). The organization of nominal instances in twin NPNs explains why it is natural that N1 and N2 are identical there too, while non-NPNs like paw in hand are possible.

Chain NPNs have plural-like meanings. This motivates nominal functions of such NPNs. Twin NPNs do not have plural-like meanings and are typically not used in nominal function. Both chain and twin NPNs are found in adverbial functions and are then adverbial NPs. When there is no case marking on N1, adverbial NPNs share a noncompositional property with other adverbial NPs: the absence of an expression specifying the relation between a trajector (external to the NPN) and the landmark meaning of the NPN as a whole (see Section 5). The implicit meaning relation is often one of manner, but also temporal and local relations are found.

This noncompositionality of the top layer of adverbial NPNs is probably the most idiosyncratic property of NPNs. Further, the emergent noun organizations sketched above are construction-specific and not found in NPs with PP modifiers in general. The tendency to lack modifiers is also a typical property of NPNs, although bare singulars tend in general to have few modifiers (Borthen Reference Borthen2003: 128).

Some NPNs are lexicalized. For instance, Norwegian side om side ‘side by side’ is the only commonly used NPN with the preposition om. The preposition here means ‘next to’, while it usually means ‘about, around’. Another example is Norwegian steg for steg ‘step by step’, which may have to do with real steps but is typically used about small abstract developments and has come to mean ‘gradually, slowly’. Lexicalization is idiosyncratic but not in focus here.

A primary aim of this article is to bring to light the regular and compositional aspects of NPNs. Irregular and noncompositional properties are acknowledged but not a primary focus. Because of space limitations, the integration of adverbial NPNs in larger constructions as well as modifiers in NPNs are dealt with only briefly, but see Kinn (Reference Kinn2021a, Reference Kinn, Neteland and Kinnb) for more detailed accounts of some such issues.

3. Bare singulars

There is solid evidence that bare singulars are sometimes used as arguments even in article languages (Section 3.1), notably in NPNs and related constructions (Section 3.2). Case marking in Icelandic corroborates this view (Section 3.3). A distinction between semantic ‘types’ and ‘instances’ provides a needed conceptual basis for an analysis of the structure of NPNs (Section 3.4).

3.1 Bare singulars in argument functions

Both English and Norwegian are languages with grammaticalized articles.Footnote 16 A restriction against bare singulars in argument functions would therefore be expected to hold for these languages, but it is known that there are exceptions.

Among the constructions with bare singulars that have been discussed for English, apart from NPNs, are the ones illustrated by John is in hospital, the way to use knife and fork, Mary is chair of the department and She is playing piano for the choir (de Swart & Zwarts Reference de Swart and Zwarts2009: 280). In Stvan (Reference Stvan, Stark, Leiss and Abraham2007), the focus is on location nouns in PPs like in hospital, but her study also documents bare singular location nouns as subjects and objects in English. Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2013) sees expressions like in hospital as special cases of a general PP construction.

Borthen (Reference Borthen2003: 68) finds that ‘Norwegian bare singulars can occur in all basic syntactic positions available for nominal phrases in Norwegian, but not “freely” in any of these positions’. She argues that the use of bare singulars is motivated by semantics, and focuses on a set of constructions where they are commonly used.Footnote 17 These are presented in Rosén & Borthen (Reference Rosén, Borthen, Rosén and De Smedt2017: 223–224) as (i) the conventional situation type construction (Hun går på skole ‘She goes to school’), (ii) the profiled have-predicate construction (Hun hadde rød ytterfrakk ‘She had (a) red coat’), (iii) the taxonomic construction (Buss er et naturvennlig kjøretøy ‘(A/The) bus is a nature-friendly vehicle’), and (iv) the covert infinitival-clause construction (Jeg vil anbefale telt ‘I would recommend (having/using) (a) tent’).Footnote 18

There are also certain genre-specific contexts like (7), where bare singulars are more generally acceptable (see Borthen Reference Borthen2003: 17):

The example in (7) is a newspaper headline, and the bareness of the nouns is dictated by headline syntax conventions. In body text, one would normally have used indefinite articles, and this use of bare singulars will not concern us further.

Some Norwegian bare singular constructions have English parallels, for example, Hun går på skole and She goes to school. The Norwegian example belongs to Borthen’s conventional situation type construction. The bare singular complements of English PPs like to school have been described by Stvan (Reference Stvan, Stark, Leiss and Abraham2007: 171) as ‘components of a predicate conveying a stereotypical activity’ (see also Goldberg Reference Goldberg2013 and de Swart & Zwarts Reference de Swart and Zwarts2009).

While constructions (i)–(iv) above are certainly central uses of bare singulars in Norwegian, there are others in addition. Rosén & Borthen (Reference Rosén, Borthen, Rosén and De Smedt2017: 239) conclude that their data may indicate that ‘bare singulars are not licensed through a set of constructions’ and that the presence or absence of the indefinite article may constitute ‘a phenomenon on a par with the choice between an indefinite [and] a definite article’. The distinction is motivated by, but not fully predictable from, referential differences between the expression types.

3.2 Bare singulars in NPNs and related uses

This section presents data that supports the view that the bare singulars of NPNs have argument properties: N2 as (head of) the complement in a PP and N1 as head of an NP.

It is illuminating to note how some NPNs shade off into NPN sequences that are not NPN constructions. The examples in (8) and (9) exhibit the same NPN sequence, but whereas it is one constituent in (8), in (9) the PN sequence is an adverbial constituent separate from the first noun, which is the subject.

Further, there are clauses like (10), where the first noun and the PN sequence are overtly separated.Footnote 19

Thus, the N1s of certain NPNs may correspond to bare singulars in ordinary argument functions, which weakens any assumption that N1 cannot be the head of a nominal NPN. Further, the PN sequences of NPNs may correspond to separate PPs with bare singular complements, strongly suggesting that they are PPs, as indicated by surface appearances.

NPN-like sequences like the one in (9) are not uncommon. The examples in (11)–(13) illustrate this for three different prepositions.

In each of these examples, the first noun is an object and is followed by a separate PP with the same noun, making the NPN sequence look superficially like an NPN construction. These PPs are valency-bound adverbials; compare Jeg satte fot foran fot ‘I put foot before (in front of) foot’ and Jeg satte den venstre foten foran den høgre ‘I put my left foot in front of the right’.

Further, there are clauses, like those in (14)–(16), where identical bare singulars are used as both subject and object:

These expressions are clearly distinct from NPNs, of course, but the referential properties of the bare singulars resemble those seen in NPNs and further corroborate Borthen’s (Reference Borthen2003) claim that bare singulars can be all kinds of arguments in Norwegian.

These facts about Norwegian bare singulars might appear to set Norwegian far apart from English, and the languages are no doubt partly different. However, uses of bare singulars very similar to the Norwegian ones exist also in English, as (17)–(19) show.

This suggests that English, too, accepts bare singulars in argument positions more readily than is commonly acknowledged. The conditions for such use must be sought in referential properties, as we will see in Section 3.4.

3.3 Case marking in Icelandic NPNs

Norwegian and English no longer have case marking of nouns that could shed light on the syntactic functions of bare singulars in NPNs. However, the nouns of Icelandic NPNs are case-marked just like nouns in other constructions.Footnote 20 In nominal NPNs, N1 carries the case of the relevant kind of argument. In (20), dagur ‘day’ is in the nominative because the NPN is the subject of the clause. (Note also the singular agreement of the verb leið ‘passed’.)

This shows that N1 is the head of the nominal NPN.

Adverbial NPs are common in Icelandic. Temporal adverbial NPs are typically in the accusative and manner adverbial NPs in the dative. This is also the case for the N1s in the NPNs in (21) and (22), which are a temporal and a manner adverbial, respectively.

The case of N1 in adverbial NPNs has a similar function to prepositions taking NPN complements, although case semantics is even less specific than prepositional semantics. The cases in (21)–(22) indicate that the case-marked N1s are the heads of adverbial NPNs.

The case of N2s in Icelandic is partly governed by the preposition, partly determined by semantics. In (22), auglitis ‘face’ is in the genitive governed by til ‘to’. In (20) and (21), dag ‘day’ is in the accusative. The preposition eftir ‘after’ governs either the accusative or the dative, and specifically the accusative in temporal expressions. This data is strong evidence that N2 is the complement of the preposition.

Old Norse, the predecessor of both Icelandic and Norwegian, had at least some adverbials like orð eftir orði [word.acc after word.dat] ‘verbatim’ (Heggstad, Hødnebø & Simensen Reference Heggstad, Hødnebø and Simensen1990: s.v. orð) and land af landi [country.acc off country.dat] ‘from country to country’ (s.v. land).Footnote 21 There have probably been several innovations in this field between Old Norse and modern Norwegian. What is clear is that adverbial NPs in general have lost their case marking. This means that the absence of an expression of their external function is the result of case loss, while the internal NP structure is otherwise retained. The Norwegian variation between, for example, adverbial time etter time ‘hour after hour’ and i time etter time ‘for hour after hour’ may be regarded as the difference between a lost case marking and a preposition which functions similarly to the lost case.

3.4 Types and instances

My analysis of NPNs below builds on the nominal semantics of Cognitive Grammar (Langacker Reference Langacker1987, Reference Langacker1991). Langacker’s notions resemble those of Borthen (Reference Borthen2003), although the semantic approaches of these two researchers may not be fully compatible in other respects. Since Borthen’s primary focus is on bare singulars in Norwegian, her approach is a natural point of departure for an analysis of Norwegian NPNs.

Borthen (Reference Borthen2003: 37) finds that bare singulars are poorer antecedent candidates for ordinary personal pronouns than corresponding expressions with an indefinite article. Thus, while en drosje in (23) is a good antecedent of the personal pronoun den, drosje followed by den in (24) sounds a bit odd.

On the other hand, Borthen (Reference Borthen2003) finds that bare singulars are good antecedents of the type anaphor det ‘that/it’ (a singular form which is neuter regardless of the grammatical gender of the antecedent), see (25).

These observations and a wealth of other evidence in Borthen (Reference Borthen2003) show that bare singulars tend to be used with a focus on the type of individual, while expressions with an indefinite article tend to be used with a focus on the individual itself. Singular nouns on Borthen’s analysis thus have a dual character, with a distinction between token discourse referents (typical focus of NPs with an indefinite article) and type discourse referents (typical focus of bare singulars). Borthen’s distinction resembles the distinction in Cognitive Grammar (Langacker Reference Langacker1987, Reference Langacker1991) between type and instance (rather than token); see also Langacker (Reference Langacker2008: 264–272). I will use Langacker’s terms in the following.Footnote 22

Let us look more closely at the distinction between types and instances by means of examples and simultaneously show how it can be used to account for the behaviour of bare singulars. The examples in (26) and (27) illustrate a common use of bare singulars in Norwegian.

In (26), the bare singular duk is interpreted as involving one single instance: one tablecloth in a specific situation (because there is one table). In (27), it will normally be interpreted as involving several tablecloth instances (since there are several tables). However, the bare singular corresponds to a singular type in both examples. The type meaning of the bare singular is a generalization over individual tablecloths with identical roles in several subevents. (The type vs. instance distinction also holds for relational predications, in this case the verbal ‘lay’; there is one instance of laying in (26) and several in (27).)

The two readings of duk are quite similar to what is found for some NPNs. An example is arm i arm ‘arm in arm’, as in (28) and (29).

For (28), the normal reading involves two arm instances, one for each bare singular. For (29), however, it is necessary to assume that there are several pairs of arms, hence more than two arm instances. The tokens of bare singular arm both invoke the ‘arm’ type, and the preposition i invokes a somewhat vague relational type. In (29), they generalize over several situations with one arm ‘in’ another.

A problem for studies of NPNs has been the discrepancy in number properties between linguistic levels (see Section 2.2). This problem can be solved if one keeps types and instances apart. NPNs have two singular count nouns, which means that one singular nominal type is invoked twice. At the instance level, an NPN may involve more than two instances, but this discrepancy in number between types and instances is a regular phenomenon for bare singulars.

4. The internal semantic structures of NPNs

In this section, the internal conceptual semantics of NPNs is detailed. First, the properties common to all NPNs are presented in Section 4.1. Section 4.2 introduces two kinds of prepositional meanings and corresponding emergent NPN semantics. Sections 4.3–4.6 deal in more detail with the prepositions and NPN semantics, while Section 4.7 discusses prepositions and NPNs where emergent meanings are not as evident.

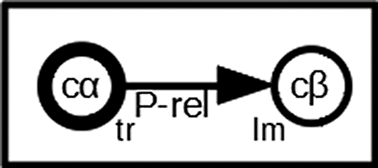

4.1 The basic schematic structure of NPNs

Figure 1 represents the internal semantic structure of the NPN schema. It involves both types and instances. Circles represent singular nominal entities, and the repeated symbol c signifies that one and the same category is involved in each case. In the type plane (TP), a singular nominal type is invoked twice (cα by N1 and cβ by N2) and therefore represented with two circles. The two are connected by a prepositional relation (arrow labelled P-rel). Thus, cα and cβ are trajector (tr) and landmark (lm), respectively.

Figure 1 The internal semantics of the NPN schema.

The type plane generalizes over an instance plane (IP) with one or more corresponding nominal instances and prepositional relations. Dashed lines indicate correspondences between types and instances. A structure with three instantiations of the relation is shown, hence six nominal instances (c1, c3, and c5 corresponding to cα; and c2, c4, and c6 corresponding to cβ). Whether the instance plane has one or more relational instances depends on context (compare The couple(s) walked hand in hand with a singular or plural subject).

In a nominal NPN, the singular trajector cα in the type plane is profiled, which accounts for the fact that subject NPNs trigger singular agreement on verbs even though cα corresponds to several instances in the instance plane.

4.2 Asymmetry and transitive and reciprocal construals

Figure 1 shows what is common to all NPNs and is limited to their internal semantic structure. The interplay between the meanings of prepositions and nouns is key to understanding how two semantic variants of NPNs emerge and motivate different syntactic properties. The emergent variants modify the structure in Figure 1 in different ways: One has landmark–trajector identity between relational instances, while the other is construed as having a reciprocal relation between trajectors and landmarks.

Prepositional relations impose an asymmetric construal on the connection between two participants, distinguishing between a trajector and a landmark. Thus, there is always pairwise ordering of participants. The asymmetry is evident in examples such as She threw the ball to the boy, where the ball is the trajector of to and the boy is the landmark. However, asymmetry is often more a matter of construal and may not be evident in the described situation. For instance, in examples such as He mixed the sugar with the flour one could often just as well have said He mixed the flour with the sugar. The asymmetry of with is here a matter of construal more than a property of the situation.

Certain prepositions have meanings that are not only asymmetric but also construed as transitive. After is such a preposition: If Kim arrives after Tim and Tim arrives after Jim, then Kim also arrives after Jim. In NPNs, the resulting construal involves nominal instances organized in what I call ‘chains’.

Certain other prepositions have meanings whose basic asymmetry may be supplemented by a construed reciprocity of the prepositional relation, if the trajector and the landmark are similar (as they are in NPNs) and tend to be directed towards each other. Against is such a preposition: In an interpretation of Kim fought against Jim, it is natural to assume that Jim fought against Kim, too, although this is not made explicit. There is a construed reciprocity with an implicitly added reversal of trajector and landmark. If the participants are very different or not directed, as in Kim fought against disease, a reciprocal construal is less motivated. Reciprocal construals in NPNs strengthen the pairwise organization of participants to form what I call ‘twins’.

The following sections discuss transitive and reciprocal construals in NPNs, as well as NPNs where an emergent semantics is not as evident. The emergent semantics will be shown to explain both the difference between *?day after night and paw in hand and the difference among NPNs in their ability to assume nominal functions.

4.3 Prepositional relations construed as transitive

Certain prepositions found in NPNs involve relations between trajector and landmark that are construed as transitive. In Norwegian, this category includes at least etter ‘after’, for ‘by’ (lit.: ‘for’), and på ‘on’. NPNs with these prepositions do not normally have corresponding non-NPNs with different nouns (compare English *?day after night). They can be used in nominal functions.

4.3.1 N etter N‘N after N’

The preposition etter ‘after’ typically designates a temporal sequence of participants. An example is dagen etter ulykka ‘the day after the accident’. The meaning is the same in N etter N ‘N after N’. The trajector is an entity that follows the landmark; in NPNs, they correspond to N1 and N2, respectively. The participants may be temporal units or other units that are somehow dealt with one after the other. The NPN in (30) is adverbial, while the one in (31) is nominal (the complement of a preposition).

4.3.2 N for N‘N by N’

The closest English equivalent to Norwegian N for N is N by N. Footnote 23 Norwegian for is highly polysemous and very commonly benefactive. However, benefactive meaning does not make any sense in N for N. Historically, the basic meaning of for is the local ‘in front of’,Footnote 24 and a metaphorical extension gives temporal ‘before’. Although now peripheral, the local meaning is found for for elsewhere too, for example, in stå for retten ‘stand before court’. N for N is mostly used adverbially, as in (32), but nominal use also occurs, like the subject in (33).Footnote 25

4.3.3 N på N‘N upon N’

The preposition på ‘(up)on’ is basically local, denoting that a trajector is placed (statically or dynamically) on top of a landmark. An example is bøkene på bordet ‘the books on the table’. This is also the basic meaning of på in N på N ‘N upon N’, but that meaning is quite frequently extended to a more general ‘in addition to’. This is congruent with the conceptual metaphor more is up.

In general, the N på N construction is construed as involving transitivity, but the transitivity of på itself is not altogether clear. In the local meaning, if A is on top of B and B is on top of C, then A is only indirectly on top of C. In the additive meaning, the transitivity is clearer: If A comes in addition to B and B comes in addition to C, then A also comes in addition to C.

Most N på N types are used nominally, like the object in (34).

A very frequent adverbial expression is shown in (35).

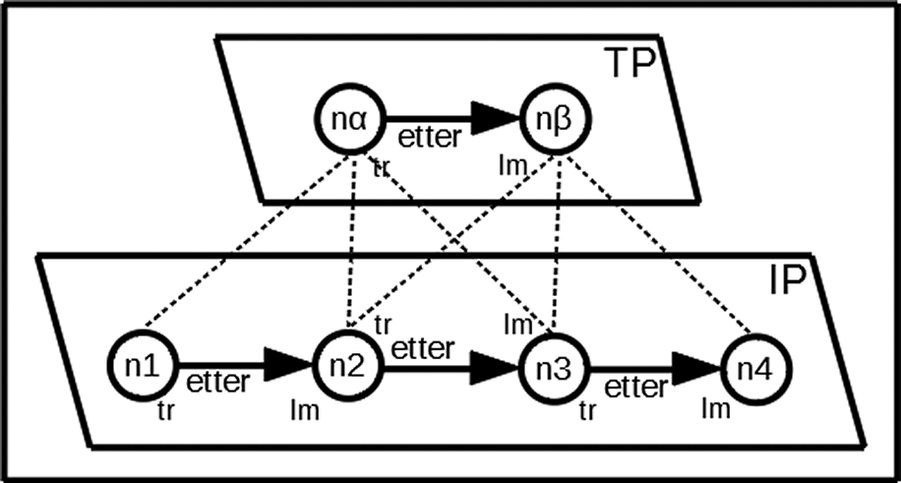

4.4 Chain NPN semantics

As seen, chain NPNs are based on construed transitive prepositional relations among participants, and some prepositions motivate such readings more strongly than others. A chain NPN designates a series or accumulation of units; for example, natt etter natt ‘night after night’ has the meaning of ‘several (consecutive) nights’, and kasse på kasse ‘crate upon crate’ means ‘several (accumulated) crates’.

The chain configuration is a property that emerges in the instance plane. In the type plane, there are only two nominal entities (one type invoked twice), in the fundamental pairwise organization of prepositional relations. But as seen in Figure 1, the type plane generalizes over an instance plane with an indefinite number of instances of prepositional relations and nominal participants.

In chain NPNs, the construed transitivity motivates the emergence of a participant configuration where the landmark of one relation instance is understood as token identical to the trajector of the next relation instance. This holds for each pair of relation instances, leading to a chain. The semantic structure of natt etter natt ‘night after night’ is illustrated in Figure 2 (see Section 4.1 above for explanation of the representation). As in Figure 1, three trajector–landmark pairs are shown in the instance plane, but because of the landmark–trajector identities, the number of different instances is smaller.

Figure 2 The internal semantics of a chain NPN: natt etter natt ‘night after night’.

The token identity of a landmark in one relation and the trajector of the following relation explains the requirement for the nouns of chain NPNs to be identical (*?day after night). A specific landmark instance (say, n2) corresponds to the landmark type (nβ) designated by N2. The trajector instance following that landmark is token identical to it (is also n2) and corresponds to the trajector type (nα) designated by N1. So n2 corresponds to both nα and nβ – and to both N1 and N2. This means that if one landmark is a night (designated by N2), then the next trajector (designated by N1) must also be a night. Therefore, N1 and N2 have to be identical (natt ‘night’). If the structure in Figure 2 were to be applied to *?day after night, ‘day’ trajectors would need to be identical to ‘night’ landmarks. The identity between nouns is thus explained without any need to resort to the reduplication assumed in some previous research.

Recall that an internal modifier like the of-phrase in layer upon layer of clothes, for example, modifies both nouns. Thus, although the constituent structure is [layer [upon [layer [of [clothes]]]]], ‘of clothes’ applies to all semantic instances of ‘layer’. On the present analysis, since the instance corresponding to N2 in one relation instance is token identical to the instance corresponding to N1 in the next relation instance, modification of N2 automatically means modification of N1. Haïk’s (Reference Haïk2013) assumption that NPNs involve coordination is therefore unnecessary.

4.5 Prepositional relations construed as reciprocal

NPNs with certain prepositions tend to involve reciprocal construals of the relations between nominal participants. These are twin NPNs. In Norwegian, at least two prepositions fall into this category, viz. mot ‘against’ and til ‘to’. NPNs with mot and til may have corresponding non-NPNs with different nouns (compare English paw in hand). They are rarely used in nominal functions (but see Kinn Reference Kinn2021a).

4.5.1 N mot N‘N against N’

The preposition mot ‘against’ is historically derived from a noun meaning ‘meeting’. It typically involves physical orientation or opposition, as in Han snudde ryggen mot veggen ‘He turned his back to (lit.: against) the wall’ and Guttene sloss mot jentene ‘The boys fought against the girls’. Note the difference between these examples: The former is not construed as reciprocal, while the latter is naturally interpreted so that the girls also fought the boys. The reciprocal construal of fighting is based on the similarity of trajector and landmark (boys and girls) and their ability to be oriented towards each other. The back and the wall are rather different entities and the wall has no clear orientation, so a reciprocal construal is not equally motivated. In NPNs, the trajector and the landmark are always of the same type. In twin NPNs, they are often persons or parts of wholes such as body parts, which are easily understood as directed. This explains the reciprocal construal of N mot N ‘N against N’. Examples are given in (36) and (37).

4.5.2 N til N‘N to N’

N til N ‘N to N’ is not a very frequent kind of NPN. Most cases have to do with people facing each other, as in (38), or people passing information back and forth, as in (39). Similar uses of til are also found outside of NPNs, for instance si noe til noen ‘say something to someone’. Til does not in itself motivate reciprocal construals, but since trajector and landmark in NPNs belong to the same category and faces and communicating people tend to be oriented towards each other, reciprocity is usually understood to be involved.

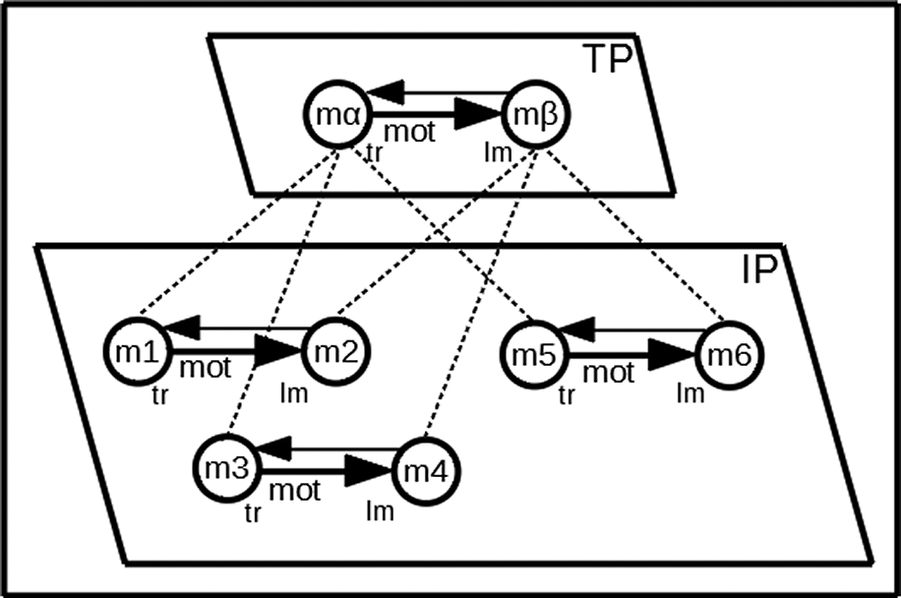

4.6 Twin NPN semantics

As described, twin NPNs are the result of construed reciprocal prepositional relations among nominal participants, and certain prepositions favour such emergent meanings more than do others. A twin NPN involves one or more pairs of participants. For instance, mann mot mann ‘man on (lit.: against) man’ is used about two and two men fighting each other,Footnote 26 and ansikt til ansikt ‘face to face’ is used (when literal) about two and two faces turned towards each other.

The semantic structure of the twin NPN mann mot mann ‘man on man’ is illustrated in Figure 3, which should be compared to Figures 1–2 (see Section 4.1 above for explanation of the representation). As before, three instances of the prepositional relation are shown in the instance plane. The actual number can be anything from one upwards and can only be determined if information is supplied from the linguistic context. In Jim and Tim fought each other man on man, for example, just two men are involved, but in The regiments fought each other man on man, there are more. In It’s tough to fight man on man, the number cannot be determined.

Figure 3 The internal semantics of a twin NPN: mann mot mann ‘man on man’.

In twin NPNs, the prepositional relation is construed as reciprocal. This means that there is not only a relationship where the participants corresponding to N1 and N2 are trajector and landmark, respectively, but there emerges a construal where the same kind of relationship has trajector and landmark reversed. In Figure 3, the emergent ‘against’-relation is illustrated with thin arrows. Whereas chain construal emerges only at the instance plane, twin construal is a property of both planes.

In such NPNs, there is no token identity between instances. The set of instances corresponding to the trajector mα and N1 does not overlap with that of the landmark mβ and N2. Since the nouns correspond to distinct sets of instances, type identity is not necessary. This explains why it is easier to tweak twin NPNs into non-NPN expressions with different nouns, for example, paw in hand: ‘Paw’ trajectors will not overlap with ‘hand’ landmarks. Still, the participants need to be fairly similar and able to be directed towards each other in order for the prepositional relation to work both ways; otherwise, no reciprocal construal is motivated. Such expressions are sometimes jocular, as in (40), but far from always, as illustrated by (41).

4.7 NPNs without clear construals of transitivity or reciprocity

While many NPNs are clear cases of chain or twin NPNs, there are also less clear cases. NPNs with certain prepositions are not strongly tied to either transitive or reciprocal construals. This pertains, for instance, to NPNs with i ‘in’ and ved ‘by, next to’. Such expressions still fit the general NPN schema of Figure 1 above. They are generally more similar to twin NPNs because they lack the very distinctive participant organization of chain NPNs in the instance plane.

4.7.1 N i N ‘N in N’

When the preposition i ‘in’ is used in NPNs, it does not have its typical containment meaning, but designates a relation of closeness and contact between a trajector and a landmark (also observed for i in certain other expressions, e.g. De holdt hverandre i hånda ‘They held each other by (lit.: in) the hand’). The participants may for instance be body parts, as in (42), or events in immediate sequence, as in (43).

(42) is most naturally construed as involving reciprocity because the hands are oriented towards each other, like in twin NPNs. (43) is rather idiosyncratic, but not unique (there are similar expressions like hopp i hopp ‘jump after (lit.: in) jump’). The ‘throws’ are connected, but not oriented towards each other like twins. Rather, they are oriented in the same direction. Therefore, such NPNs come to be construed as involving a chain of instances.

4.7.2 N ved N‘N (next) to N’

The preposition ved ‘by, next to’ typically has a local meaning. The trajector and the landmark are close, in various ways understood as having their sides next to each other. Two examples of NPNs are given in (44) and (45).

Example (44) has a reciprocal twin construal, of pairs of individuals fighting with their shoulders next to each other, supporting each other. The example in (45) is not altogether clear. But it seems that the palm gardens are construed as forming a chain, because langs strandpromenaden ‘along the beach promenade’ indicates a stretch that would accommodate a number of gardens in a line along the promenade.

5. The external connections of NPNs

Some NPNs are normally only used as adverbials, while others are also used in nominal function. This can be explained on the basis of twin and chain semantics (Section 5.1). Adverbial function involves an extra semantic layer (Section 5.2). Adverbial NPNs have variable semantic roles, at least manner, time, and distance (Section 5.3).

5.1 Nominal vs. adverbial function

All kinds of NPNs appear to be able to have adverbial functions, but the range of NPNs that function nominally is restricted. In English, this is mostly NPNs with after and (up)on, and in Norwegian, primarily those with etter ‘after’, for ‘for’, and på ‘(up)on’ (see Section 4.3). All of these are chain NPNs. Twin NPNs are only rarely used in nominal functions (see Section 4.5 above and Kinn Reference Kinn2021a).

A chain NPN involves a series of instances, similar to a plural noun meaning. The plural-like meaning is what makes it a viable candidate for nominal syntactic functions. The strengthening from a minimum of two instances to ‘several’ and ‘many’ is found also in certain ordinary plurals, for example, English Years have gone by. The main departure from an ordinary plural is the sequential ordering of instances. Another is that, as the head of the NPN, N1 in subjects triggers singular verb agreement, at least in English and Icelandic.

A twin NPN involves one or more pairs of instances that are construed as reciprocally related. The twins in a pair are oriented towards each other and away from other pairs. The participants are construed more in terms of that special configuration than a plurality. This makes twin NPNs less viable for nominal function, and better suited as manner adverbials. Thus, the syntactic difference between chain and twin NPNs is explained by their semantics.

With nominal functions being somewhat peripheral in the grammar of NPNs, one might speculate that adverbial functions are historically primary for all NPN types in Germanic languages, including chaining ones. Their origin would then be case-marked adverbial NPs, and nominal function would be an innovation. This hypothesis needs to be explored on the basis of historical language data. At present, I have no solid basis for substantiating or disproving it.

Chain NPNs with etter, for, and på are the most productive NPN types in Norwegian (see Kinn Reference Kinn2021a), and it might be that productivity and extension from adverbial to nominal use are related. It should be observed, however, that low-frequency chain NPNs like Norwegian N bak N and the English equivalent N behind N do sometimes occur in nominal functions, as in (46) and (47):

5.2 The additional layer of adverbial NPNs and internal vs. external modifiers

Nominal NPNs are connected to embedding constructions through being participants of relations, mainly expressed by verbs (NPNs as subjects and objects) and prepositions (NPNs as complements). In such cases, the NPN profiles the meaning of N1, as illustrated in Figure 4 with the thicker line around cα. For simplicity, the distinction between types and instances is omitted here.

Figure 4 Profiling in a nominal NPN.

Adverbial NPNs have the same overt internal nominal structure, but they have an additional semantic layer that turns them into modifiers in embedding constructions – mainly adverbials. In Norwegian and English, there is no overt expression of how the NPNs connect to other syntactic constituents. In this, they are like other adverbial NPs.

Such adverbial NPNs are semantically argument-taking constituents comparable to, for example, prepositional phrases. This is seen in a comparison of Jeg venta i time etter time ‘I waited for hour after hour’ and Jeg venta time etter time ‘I waited hour after hour’. The latter sentence may be said to involve the same temporal relation between waiting and duration as is designated by i ‘in’ (English for) in the former, but it is not expressed by any morpheme. The meaning of both expressions is illustrated in Figure 5. The basic nominal NPN meaning from Figure 4 has here become the landmark of a relation (called ‘rel’, to cover both the implicit relation of the adverbial NPN and the prepositional relation expressed by i ‘in’). The trajector square signifies whatever is the external participant (the waiting in the sentences above). The profile is the higher relation. This means that if it is left implicit, no constituent of the adverbial NPN has the same profile as the NPN. Adverbial NPNs are therefore exocentric constructions – a noncompositional, but not entirely irregular feature.

Figure 5 NPN meaning as the landmark of a higher relation (prepositional or implicit).

I consider the semantic integration of an adverbial NPN in an embedding construction to be noncompositional because of the lack of an expression of its semantic role (in non-case languages). This does not preclude, however, the possibility of analyses that attempt to determine the semantic role on the basis of the overtly expressed meanings of (the words in) the NPN, the head of the embedding construction (usually a verb), and other constituents of the embedding construction. After all, language users need to do something similar in order to be able to produce and understand utterances involving adverbial NPNs, and it is what I do in Section 5.3 below, on an intuitive basis as a native speaker of Norwegian.

It may reasonably be questioned whether twin NPNs, which normally do not have nominal function, can meaningfully be considered to involve NPs. This should be seen in the light of case marking. As shown, Icelandic adverbial NPNs have a case marking on N1 that goes some way towards expressing the external relation that is left implicit in adverbial NPNs in Norwegian and English – ‘some way’ because the accusative and dative cases in Icelandic are even more polysemous and multifunctional than prepositions. Norwegian adverbial NPNs are almost exactly like Icelandic ones – except for the case marking. It would take strong empirical evidence to show that adverbial NPNs in these closely related languages have markedly different structures. They all have the internal structures of NPs.

Two common kinds of modifiers in NPNs were illustrated in examples (3) and (4) in the introduction, and the difference can now be explained. They are hierarchically integrated in different ways, as shown in Figures 6 and 7.Footnote 29

Figure 6 Constructional representation of a nominal (object) NPN with an internal modifier: ‘drink glass upon glass of wine’.

Figure 7 Constructional representation of an adverbial NPN with an external modifier: ‘stand face to face with the enemy’.

Internal modifiers as in Figure 6 were discussed in Section 4.4. External modifiers are constituents of the exocentric adverbial NPN construction. While the nominal part of the NPN is a complement of the implicit adverbial relation, such a modifier takes the adverbial relation as its trajector. In the case of a PP modifier, the landmark is the complement meaning; in Figure 7, med connects the manner relation of ‘face to face’ to the companion ‘the enemy’.

5.3 The semantic roles of adverbial NPNs

The distinction between twins and chains proves to be important not only for adverbial vs. nominal function, but also with respect to the variable semantic roles of adverbial NPNs. Twin NPNs in Norwegian are normally manner adverbials, as possible answers to the question ‘how?’. Such expressions tend to involve nouns for body parts or parts of other kinds of objects, the wholes typically being the subject referents. Examples are given in (48)–(50).

The semantic roles of adverbial chain NPNs are more variable. N på N ‘N upon N’, as in (51), exhibits the least variation; all adverbials seem to be expressions of manner, except the temporal gang på gang ‘time after time’ (see below).

The manner role is frequent for N etter N ‘N after N’ and N for N ‘N by N’, too; (52)–(53) illustrate this.

N for N ‘N by N’ and especially N etter N ‘N after N’ with nouns denoting time units can be temporal adverbials (of duration, location, or frequency, possible answers to the questions ‘for how long?’, ‘when?’, and ‘how often?’), rather than manner adverbials. This is exemplified in (54) and (56). The highly frequent gang på gang is illustrated in (55).

Uke etter uke in (54) is an expression of duration; it describes the length of time that ‘he’ spent in bed. Gang på gang in (55) is an expression of frequency. With N for N ‘N by N’, the difference from manner is not always obvious. In (56), år for år may be interpreted as describing the manner of distribution of increase over years, but another reasonable interpretation is that it describes the temporal location of increase in each successive year.

Further, N etter N adverbials with nouns denoting length units, as in (57), typically refer to distances. Here, kilometer etter kilometer does not describe the manner of running, but rather the distance (a possible answer to the question ‘how far?’).

When the instances of the NPN meaning are co-extensive with the meaning of some other constituent of the clause (especially the subject), manner adverbials may blend into secondary predicates (essive meaning). This goes for both twin and chain NPNs. An example with twin N mot N ‘N against N’ is given in (58).

This NPN may be taken to describe the manner of settlement. Another imaginable interpretation is that it describes the subject referents rather than their action.

While the latter alternative is not obvious in Norwegian, it is clearer in Icelandic. For instance, in the NPN maður gegn manni in (59), N1 maður is not in the dative case typical of manner adverbial NPs, but in the nominative case of a subject predicate. (The dative on N2 manni is governed by gegn.)

As has become clear, NPNs assume various functions in embedding constructions. Their internal semantics partly determines their possible external connections. Only chain NPNs normally assume nominal functions. Adverbial NPNs, like other adverbial NPs, have an implicit semantic role in the embedding construction. In Norwegian, most adverbial NPNs express manner, but some pertain to duration, frequency, temporal location, or distance, and some resemble secondary predicates. The construals involved in the external semantics of adverbial NPNs deserve more detailed exploration in future research.

NPNs are involved in a number of complex phenomena that have not been explored here, for instance aspectuality. One issue that has occupied some researchers is plurality of events (e.g. Beck & von Stechow Reference Beck, von Stechow, Evert and Endriss2005, Reference Beck and von Stechow2007). Especially the use of chain NPNs tends to indicate multiple events. In (55) above, the use of gang på gang ‘time after time’ expresses directly an iteration of the whole event. In (53) above, the use of patron for patron ‘cartridge by cartridge’ brings to the fore the subevents of the clip loading, which would otherwise have been construed holistically. Much remains to be explored in this field.

6. Conclusion

Previous research has sometimes seen NPNs as idiosyncratic and resisting analyses as more ‘well-behaved’ regular and compositional constructions. My objective has been to show that NPNs are less idiosyncratic than generally recognized. All NPNs involve an NP headed by N1. The PN sequence is a modifying PP with N2 as (head of) its complement. Categorizing NPNs as NPs with PP modifiers implies that they inherit regular properties of more general NP and PP constructions.

As NPs, NPNs are expected to assume nominal functions. The fact that most of them are adverbials is their clearest noncompositional characteristic. An adverbial NPN has the form of an NP but involves an additional semantic layer that makes it an exocentric construction with modifier function in the embedding construction.

It has been shown in some detail how bare singular count nouns do sometimes function as arguments in article languages. This is not a novel move but one that was made forcefully for Norwegian already by Borthen (Reference Borthen2003). Others have done similar work for other languages, like Stvan (Reference Stvan, Stark, Leiss and Abraham2007) on English. Bare singulars can be effectively analysed in a construal-based semantics employing a distinction between types and instances. The bare singulars of NPNs share properties with bare singulars in general.

The prepositions involved in NPNs are clearly ‘real’ prepositions, designating a relation between a trajector and a landmark designated by N1 and N2, respectively. Most prepositions favour one of two kinds of relations between participants: reciprocal or transitive. In turn, this leads to emergent construals where the nominal instances are organized as either twins or chains.

Both chain and twin NPNs assume adverbial functions, and twin NPNs are only rarely nominal. The chain organization of instances in chain NPNs is what facilitates nominal function for such NPNs. The deeper cause is that chain organization resembles pluralization while twin organization does not. The semantic difference between twin and chain NPNs thus explains a fundamental syntactic dichotomy among NPNs. Chaining further explains why the nouns of chain NPNs must be identical, while the participant organization in twin NPNs makes NPN-like expressions with different nouns more acceptable. The present analysis explains the plural-like and coordination-like properties of chain NPNs without resorting to assumptions that the preposition is a quantifier or coordinator, or that N1 is reduplicated from N2.

Nominal NPNs receive their semantic roles from the heads of embedding constructions, usually a verb or preposition. The semantic roles of adverbial NPNs, on the other hand, are implicit in non-case languages, as they are with all adverbial NPs. In a case language like Icelandic, the cases indicate such roles vaguely. Adverbial twin NPNs appear to be restricted to manner expressions. Adverbial chain NPNs are often manner adverbials, too, but locative and especially temporal adverbials are also common. The semantic role of adverbial NPNs involves an interplay between the meaning of (the words of) the NPN and the meanings of the head and other constituents of the embedding construction which should be studied more closely in future research.