Iconic revenge tragedy of a brooding hero trapped in a family melodrama and an existential crisis

Key Facts

- Date:

1600

- Length:

3,904 lines

- Verse:

75%

- Prose:

25%

- Hamlet

37%

- Claudius

14%

- Polonius

9%

- Horatio

7%

- Laertes

5%

Major characters' share of lines:

Plot and characters

The Ghost of the old King Hamlet appears on the castle battlements to Bernardo, Marcellus and Horatio: they vow to report it to his son Hamlet. Claudius, the new king, has married his brother’s widow Gertrude. He dispatches ambassadors to deal with young Fortinbras, who wants to regain lands lost by his father during the previous reign. Hamlet is distressed and melancholic at his father’s death and his mother’s remarriage, but accedes to the request that he stay at court. Laertes, son of the councillor Polonius, is given permission to go to Paris: taking leave of his sister Ophelia, he advises her against her relationship with Hamlet. Polonius secretly sends Reynaldo after him to report on his behaviour. Hamlet meets the Ghost and hears that he was murdered by Claudius: he vows revenge and makes Horatio and the others swear an oath of secrecy. He feigns madness to cover his plans. Claudius and Gertrude employ two fellow students, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to spy on Hamlet, but he suspects them. Polonius maintains he is lovesick for Ophelia, and sets her as a bait for the King to watch Hamlet’s behaviour. Hamlet rejects Ophelia harshly and denies he ever loved her. A company of Players arrive whom Hamlet knows well; he arranges that they will modify a play in their repertoire and that this will make the King reveal himself. The performance of the ‘Murder of Gonzago’ ends in confusion when Claudius leaves. Hamlet has the opportunity to kill him, but believing he is at prayer and will thus go to heaven, he does not take it. In his mother’s chamber he berates her about the death of his father; she says she knows nothing about it. Hamlet kills Polonius, who has been spying on them, thinking he is Claudius. Claudius sends Hamlet to England with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, where he will be killed. Driven mad by the death of her father, Ophelia drowns. Laertes returns and is persuaded by Claudius to direct his anger towards Hamlet. At Ophelia’s funeral, Hamlet returns, having escaped from the ship via some pirates, and sends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to their deaths. He and Laertes fight in Ophelia’s grave. Claudius plans Hamlet’s death with Laertes: he will poison the foils in a fencing match. Hamlet accepts the challenge brought by the foppish courtier Osric, and in the fight he and Laertes are both mortally poisoned; Gertrude dies from drinking poison intended for Hamlet, and Hamlet kills Claudius before dying in Horatio’s arms. Fortinbras enters to take over the battered kingdom.

Context and composition

The date of Hamlet is difficult to ascertain: there are two distinct early printings, in 1603 and 1604, which may in part represent different stages of Shakespeare’s work on the play. Stylistic evidence tends to place it around 1600, although there are references ten years earlier to a play on the same subject, almost certainly not by Shakespeare but assumed by many to have been one of his sources – the so-called ‘Ur-Hamlet’. Other sources for the play are the Norse story of Amleth, available to Shakespeare in a French version, and Thomas Kyd’s popular Elizabethan revenge play The Spanish Tragedy, which also has a ghost, a character called Horatio and a play-within-a-play. Shakespeare’s transformation of this material is thoroughgoing – the depiction of Hamlet’s internal state, revealed through soliloquy, is perhaps the most striking change of emphasis from his more plot-driven predecessors. Shakespeare also brings out the parallels and foils in the story – Laertes and Hamlet, Hamlet and Fortinbras – and compounds the sense of self-loss in his father’s death by splitting the name Hamlet.

Close in date to Hamlet is another story of the aftermath of regicide, Julius Caesar, to which the play alludes when Polonius talks of playing the title role. Together these two plays usher in the political and personal concerns that will dominate the later tragedies.

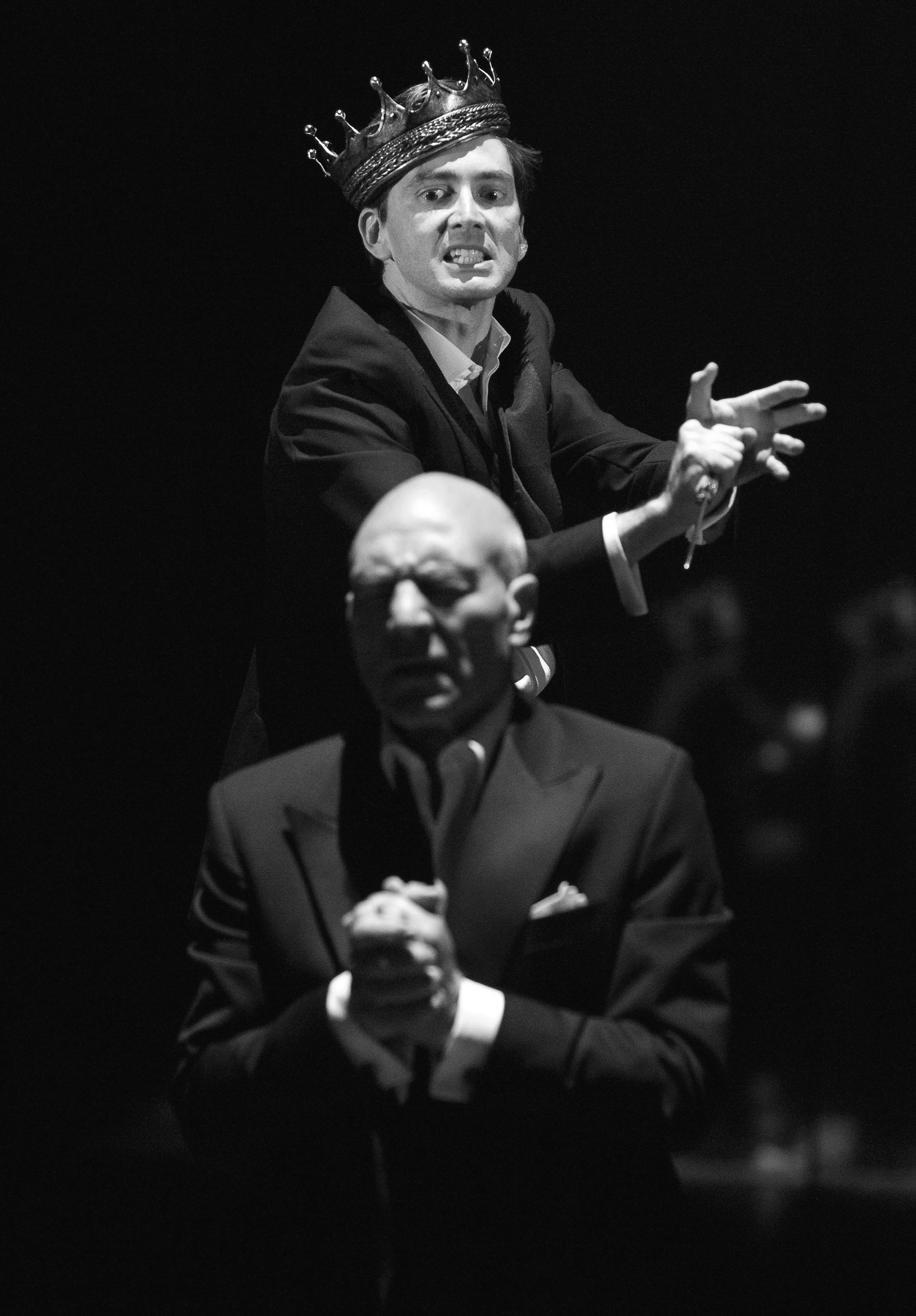

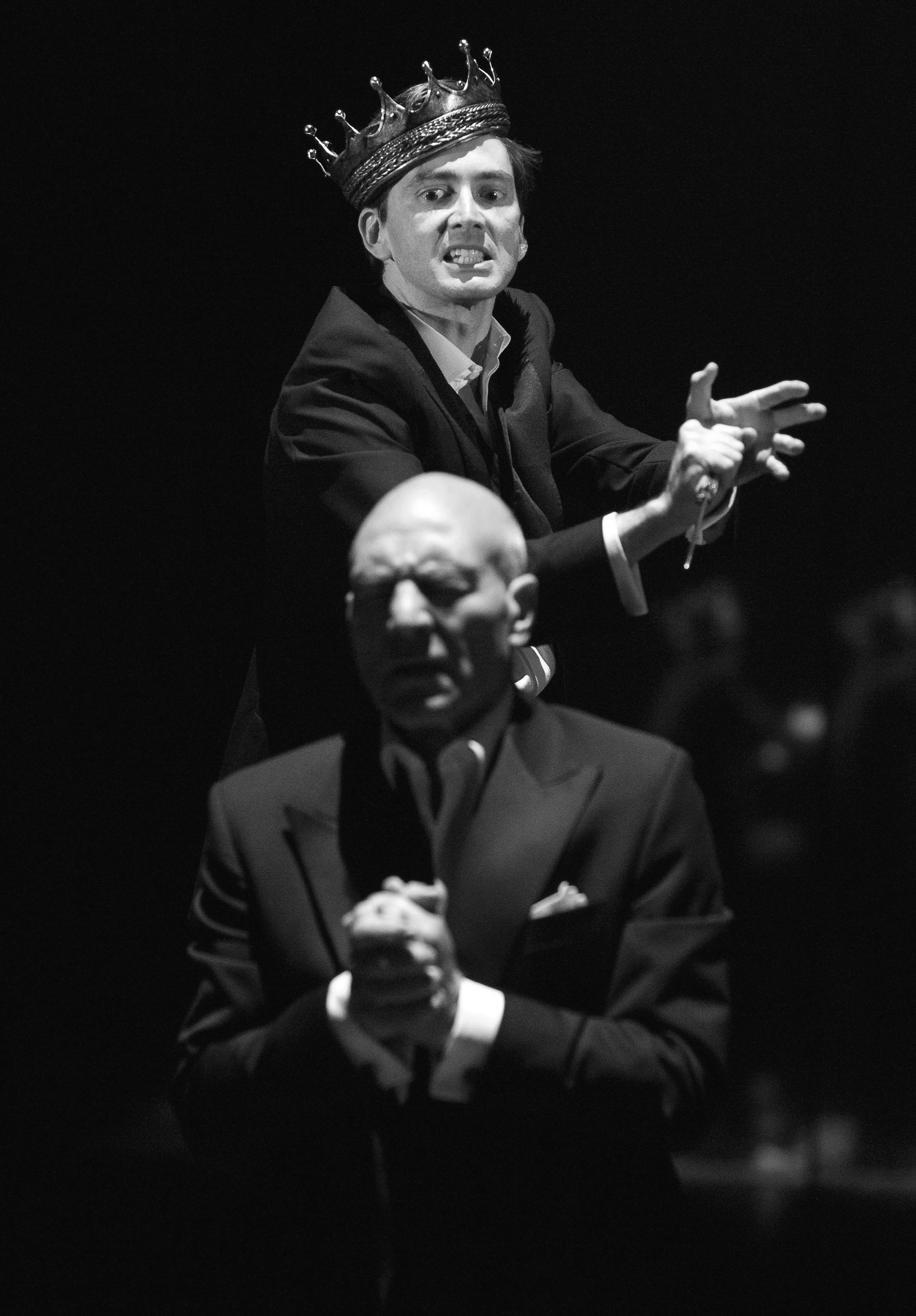

Performances

Themes and interpretation

Hamlet begins with a question: ‘Who’s there?’ (1.1.1). In context it registers the nerviness of the nightwatch, but it soon expands into a more existential summary of the play’s themes, and particularly of its insistent questioning of issues of identity and recognition. It is this inexhaustible interrogation that has given Hamlet its unique hold on western culture, and its ability to adapt to speak for new audiences across the centuries. This revenge play steeped in the traditions of the Elizabethan theatre has, in its depiction of psychological trauma and isolation, come to stand as a monument to consciousness itself.

It is appropriate that the most recognisable visual image of the play is from Act 5, Hamlet’s encounter with the gravediggers who are displacing old bones as they dig a new grave. Facing the skull of the jester Yorick, Hamlet represents the encounter with human mortality, and with the inevitability of death. For Hamlet himself this fate is sealed once he takes up the ghost’s injunction to revenge, since stage revengers had to pay with their own lives, but he is already sickened with grief and weary of life before he hears this terrible summons. The twentieth-century playwright Arthur Miller’s observations on tragedy seem particularly appropriate here: ‘I believe, for myself, that the lasting appeal of tragedy is due to our need to face the fact of death in order to strengthen ourselves for life’ (preface to Collected Plays; 1958). What makes this confrontation with death so modern is that there are no comforting pieties about the afterlife. Hamlet embraces death as a sleep but then fears nightmares; the Ghost is an unquiet presence from beyond the grave; Polonius’ corpse is so much decomposing lumber. Hamlet comes finally to the realisation that ‘the rest is silence’, and Horatio’s ‘flights of angels sing thee to thy rest’ (5.2.337–9) seems an overoptimistic gloss from the previously rational student.

Since at least Freud, readings of Hamlet’s character have been interested in his inner motivations and in his fractured relationships with women. (A film of 1976 by Celestine Coronado cast Helen Mirren as both Ophelia and Gertrude, to bring out their similarity in Hamlet’s jaundiced view.) The play’s misogyny is unavoidable and probably reflects attitudes at the end of Elizabeth’s long reign, when the play was written: it is striking that Claudius likens his murder of a brother and a king to ‘the harlot’s cheek, beautied with plastering art’ (3.1.51), just as his nephew ‘must like a whore unpack[s] my heart with words’ (2.2.538). In this context Gertrude’s own protestation that she knew nothing of the death of her first husband has rarely been believed. But while scenes of violent intimacy between Hamlet and his mother when he visits her private chamber and discusses her sex life may parody Freudian interpretations (one reviewer of Franco Zeffirelli’s 1990 film version with Glenn Close and Mel Gibson as mother and son called that scene ‘ghostus interruptus’), the hold of melancholy and unresolved mourning on Hamlet’s psyche is abiding. His has often been seen to be a distinctly modern alienation, and although the play does draw extensively on succession anxieties at the end of the Elizabethan period and on the literary heritage of revenge tragedies, it has come to be seen as Shakespeare’s most timeless work. A succession of modern-dress Hamlets from the eighteenth century onwards has asserted the enduring aspects of his situation. Hamlet has become Hamlet: less a story than an individual personality in which the specific details of the melodramatic plot are erased by the force of Shakespeare’s representation of inner cogitation and distress. Horatio’s summary of events in the play’s closing lines: ‘carnal, bloody, and unnatural acts, / Of accidental judgements, casual slaughters’ (5.2.360–1) is laughably inadequate. What really happens in this play is a matter of the interior rather than the exterior; it is psychological rather than physical; and it is structured not around the crime and retaliation of the revenge tragedy genre but by rhetoric, punctuated by soliloquies that decisively displace action into reflection.