Introduction

Recent conflict research has explained the rise and persistence of civil wars through exclusive and biased political settlements and institutional arrangements. Regime replacement and civil war is robustly associated with political exclusionFootnote 1 and horizontal and vertical inequalities in representation.Footnote 2 Indeed, with the adoption of democratic and participatory institutions, civil wars have declined precipitously across Africa. Almost all African states are now characterised as semi-democracies, electoral autocracies, hybrid regimes, or ‘competitive autocracies’.Footnote 3 These same governments adopt institutions like cabinets, parliaments, and independent judiciaries to distribute power, encourage political competition through elections and opposition parties, and check the power of the executive through term limits.Footnote 4 As a result, African states are strongly inclusive in senior, key institutions.Footnote 5 Governments with autocratic practices and ‘functional’ quasi-democratic institutionsFootnote 6 aim to integrate, rather than sideline ethno-regional political communities.

However, ‘inclusive’ governments are not peaceful; most African states experience some form of sustained political violence by militias and non-state groups after the adoption of democratising institutions. The political violence patterns in such states rarely assume a ‘civil war’ form, where at least one main armed group has an intention of removing the regime. This political violence involves a myriad of political motives, patrons, and strategies against the state, civilians, and armed non-state groups. Common forms include threatening voters, competing with other political elites, providing security for a defined group, harassing other identity groups, operating as substitute police or military enforcers and engaging in local rent seeking.Footnote 7 This type of violence has drastically increased in the past two decades, while rebel violence and insurgencies have largely declined, and this change in the main modality of conflicts suggests that institutional changes may depress the likelihood of one form of conflict, like civil wars, while increasing the incentives for others. The presence of inclusive institutions and widespread group representation may be important contexts to explain why civil wars have abated, but these factors do not have the same influence on the occurrence of political violence across states. It is clear that conflict agents are adapting to different domestic political arrangements and distributions of power.

How does the composition of an inclusive government influence conflict? We address how levels and variants of political representation at senior levels of government are associated with the form and occurrence of political violence. Our work is part of a longer tradition of explaining political violence patterns and forms through the distribution of power within states, and is a continuation and refinement of explanations where violence is used as a strategy through which political groups compete with each other. We argue that violence adapts to the distribution of power and the dominant forms of political competition. For example, with the adoption of inclusive, formal political institutions, African regimes widened the composition of group representation in formal offices. But these same institutions and elites have served to promote and propagate internal regime practices that determine and secure appointments, rents, and access to power.

These practices have increased levels of ‘competitive clientelism’ at the senior scales of government, where groups and their elite representatives use political violence against the state and each other to secure access to authority, positions, and proximity to the leader. In these inclusive and competitive regimes, levels of absolute representation and levels of political exclusion are not closely related to conflict rates. Instead, mal-apportionment of positions between groups in formal roles is a key measure of the competitive context that encourages groups and elites to engage in violence. The use of conflict is a key strategy to increase a group and elite's relative leverage in their competition to secure positions, authority, and rents.

We develop new theoretical avenues and support our hypotheses by using data on cabinet representation in governments on a monthly scale. The African Cabinet and Political Elite Data Project (ACPED) measures how groups and elites are accommodated in government by compiling detailed information on cabinet appointments and ministerial characteristics, by month, over the past twenty years.Footnote 8 We compare the characteristics and rates of time varying senior cabinet representation to political violence rates and forms across African states. These cabinet, political elite, and group representation data improve significantly on the existing measures of group representation in government, which provide overly static, aggregated community positioning in central government or annual aggregate information on cabinet positions from the past.Footnote 9 These previous data projects largely overlooked the changes in elite politics, appointments, and government strategies of inclusion, which, we believe, underscore the competitive clientelism that has arisen across African states.

Using these data, we develop a compelling explanation for increased political violence through competitive clientelism among group representatives and senior elites. We demonstrate that leaders are dependent on mutually beneficial political alliances made with a wide range of subnational elites, and through this inclusion process, many political elites are granted preferential access to political and economic organs of the state.Footnote 10 This process of mutually beneficial bargaining ‘among contending elites’Footnote 11 is associated with considerable regime longevityFootnote 12 and is referred to as the ‘politics of survival’Footnote 13 or the ‘political marketplace’.Footnote 14 But such transactional politics are not stable or without conflict. Many African states suffer from representation volatility and imbalance at the senior levels of government, and those variations at the elite level are closely correlated to the occurrence of political violence throughout the state. As elites and their supporters are keenly aware of the competitive and transactional environment that inclusive political representation has generated, they are willing and able to use political violence as an effective tool of competition, political manipulation, and intra-elite negotiation. Our findings reflect pragmatic political calculations: in states with high levels of ethnic inclusion, if representatives of large or wealthy communities fail to acquire a due share of ministerial positions, higher levels of political violence are expected. Similarly, if small communities acquire too much power relative to their size, higher levels of political violence are also expected.

The larger significance of these findings is that we show that conflict arises from a contest for power, not its absence; and rather than a resort of excluded groups, political violence is mainly used by groups who have high levels of inclusion. Groups and elites engage in conflict to increase their power share, even if they have a highly favourable proportion of senior authority. Therefore, the imbalance of power between included senior elites is a better predictor of which countries are at risk for increased political violence than theories about ethnic exclusion.

Exclusion, grievances, and institutional corrections

Many of Africa's governments are regarded as active autocracies,Footnote 15 with adjustments for the particular institutional and personalist characteristics.Footnote 16 A common presumption is that governments in these states have an unequal representation of groups in a patronage-based system, active marginalisation of minority groups, with disproportional authority going to a leader's home group and region.Footnote 17 In such cases, political exclusion is a proxy for grievanceFootnote 18 and a necessary and sufficient prerequisite for political violence. But assumptions about the exclusive characteristics of African autocracies has stifled inquiry into how representation transcends measures of inclusion and exclusion, and how regimes have built highly representative government institutions over the past twenty years.

An ‘African institutionalism’ literature argues that ‘formal institutional rules are coming to matter much more than they used to’Footnote 19 in contrast to an ‘almost [exclusive] focus on … clients and patrons … which … largely ignored the institutional environment in which the transactions between them take place’.Footnote 20 Regimes have engaged more and varied political elites in legislaturesFootnote 21 and cabinets; institutional devices, such as election committees, that can mediate political outcomes are more widely present;Footnote 22 leaders are curtailed by presidential term limits;Footnote 23 decentralisation projects have curbed personalist power;Footnote 24 regimes have to engage with inter-regional and group integration systems;Footnote 25 and party systems within regimes nominally act as a system of checks on the executive.Footnote 26

But autocracy and ‘new institutionalisation’ research findings diverge in their interpretation of modern African regimes. One argues that institutionalisation is a steady path to representative democracy, highlighting how the state increasingly mediates and limits personalist practices and engages in extensive inclusive representation. Due to these constraints, the power balance favours voters and elites as constituencies, who in turn have more opportunities to exercise power. A second, more functionalist, literature suggests that the greater role of (quasi-) formal institutions is not evidence of a democratic progress. It maintains that the inner workings of African power adapt to the new reality and remain unaltered,Footnote 27 and institutions are adopted to support regimes and leaders, rather than as a constraint to central authorities.Footnote 28 Regimes incorporate an extensive range of ethno-political representatives in order to promote regime survival, rather than representing alternative power holders. While nominally adopting democratic practices, regimes and leaders ‘keep power by spreading it around’;Footnote 29 integrating politicians from different ethnic groups into their coalitions has allowed African leaders to effectively consolidate power.Footnote 30 Leaders extend and consolidate their regimes by co-opting elites and their constituencies, and endanger regimes if they did not integrate other powerful domestic agents to secure continued power and extend authority across the state.Footnote 31

A regime's ruling coalition adapts to their state's social heterogeneity, but the lack of absolute ethnic or regional majorities in many African countries means that leaders cannot rely on their own groups for political support to maintain power.Footnote 32 To acquiesce to co-ethnics or demographic minorities would place leaders in a weak, vulnerable position.Footnote 33 For regimes in politically heterogeneous societies, cross-group inclusive coalitions are the best strategy for leaders to secure a majority or plurality.Footnote 34

Regime maintenance strategies guide leaders on ministerial appointments, dismissals, and reshuffles.Footnote 35 A dramatic increase in ministerial posts during periods of democratisation allowed leaders to redistribute material and symbolic rents from the centre and strengthen ties with their regional and political constituencies.Footnote 36 In these cases, large coalitions are optimal and serve as an effective strategy for facilitating intra-elite accommodation and warding off forced removal. Creating an inclusive and expansive coalition that can co-opt potential political opponents and their constituents can limit the capabilities of opposition coalitions and further enhance the incumbent's chance of re-election. In short, regime survival in a changing political landscape necessitates an inclusive, transactional approach to elite and group representation. The implication of such functionalist political change is that representation has an alternative logic other than power sharing and operating as a check on the executive, and democratisation is an insufficient explanation for widespread senior representation across African governments.

Representation, communities, and elites

But who and what is necessary to represent? Politics in Africa remains strongly shaped by ethno-political and regional identities due to bloc interests, political support, and patronage.Footnote 37 Ethnic groups can provide ‘a form of minimum winning coalition, large enough to secure benefits in the competition for spoils but also small enough to maximize the per capita value of these benefits’;Footnote 38 bloc interests prevent non-members from participating in the allocation of political goods.Footnote 39 In turn, voters support parties that represent interests of their politically-relevant identity group and exclude others,Footnote 40 allowing leaders and elites to frame the stakes of political contest in often ethno-regional terms that emphasise reciprocity.Footnote 41 These explanations suggest that representative elites can claim to ‘have the support’ of their communities and use votes and group size as a form of political leverage. While ethnic associations between elites and groups can confer an automatic legitimacy due to a ‘constituent pay off’, appeals to bloc interests are rarely a sole or consistent motivator in political support. Further, the degree of exchange between representation and patronage allocation is contested,Footnote 42 as resources generally remain in elite hands and do not extend out past a small circle of followers.Footnote 43 Yet senior elite representation is necessary for any possible return on political influence as few other equitable, accessible opportunities are available for groups.

To return some amount of favour and rents to their constituent community, elites must climb the political hierarchy and control the distribution of patronage opportunities. To do so, subnational elites leverage their ethnic, regional, or financial associations in their transaction with regime leaders for positions. Relying on the loyalty principle, any elite and group benefiting from government positions may be less likely to upset the regime and, only under extreme circumstances, destabilise a leader. Access to positions is so crucial that included elites are wary of jeopardising their privileged position and rarely push for political reform, and even opposition politicians frequently accept offers for inclusion from the regime.Footnote 44 Footnote 45

Representation vs malapportionment tactics

Representation through senior government appointments can assess how elites and groups are positioned in a regime at any time. There are at least two ways to integrate and measure elite and group levels of power: any appointed position constitutes a claim of representation in national government, while the number and quality of positions allows for an assessment of proportional power between elites and groups. Leaders both include elites in senior positions to sustain high levels of group representation, and manipulate elites and group power through the distribution of appointments. There is an intricate logic to accommodation and inclusion that is both transactional and increasingly formal: leaders arrange the distribution of offices and associated rents, and these exchanges are the main ways to secure commitment between the elite and the leader.Footnote 46 Elites navigate these systems and compete for positions internally by maximising their community leverage, regional affiliations, socioeconomic ties, and ability to suppress threats. Groups and their associated elite representatives differ in their comparable political weight, and leaders recognise and manipulate those variations in elite leverage for their benefit, through exaggerating or limiting their authority, or by taking advantage of intra-elite competition.

Through appointing elites to positions in often very sizeable cabinets, leaders create multiple ethno-political configurations.Footnote 47 Regimes that are inclusive and score highly on ethno-political representation may have a malapportioned – or imbalanced – government where one or a few ethno-regional groups have a ‘disproportionate’ share of cabinet positions. On the other hand, an exclusive regime with low levels of cross-group representation may distribute power equally across elites that are included in government, favouring none.

Why generate an imbalance among included senior elites? Leaders must both hold a coalition together but not advantage any potential threats. Ruling coalitions in which power is dispersed and balanced among senior members can limit the autonomy of the incumbent and lead to political gridlock.Footnote 48 There are several ways that regimes actively distort this body to their benefit: they can ‘pack’ the cabinet, limiting the power of strong, potential challengers by giving positions to elites from many small communities. The appointment of small group elite representatives in cabinet can rarely be explained by political-demographic leverage; instead, growing the cabinet through short-term positions for small groups enhances a leader's senior support base through ‘useful’ alliances. These appointments reinforce the loyalty principle and allow regimes to appear ‘inclusive’. Regimes also ‘counterbalance’, creating multiple versions of the same department or positions within government to keep possible competitors weak and disorganised, while creating new allied recipients of patronage.Footnote 49 Footnote 50 Regimes further bias representation by letting positions accrue to powerful elites who represent strong independent communities. The support of these elites and groups can be more important to capture than the support of those with weaker constituencies, as long as their local authority is contained.

Countries that are inclusive may have a highly imbalanced government where one or a few groups have a ‘disproportionate’ share of cabinet positions. Many strategies may disproportionately benefit a leader's co-ethnics by prioritising the allocation of key government positions, or conversely may limit co-ethnic power because of the guaranteed support of that constituency.Footnote 51 These practices can involve the co-option of potential rivals into government with mutually beneficial arrangements, in practices known as ‘coup proofing’. Yet, supporting rivals as a tactic for sustained ruleFootnote 52 is overstated in researchFootnote 53 as the imbalance of senior elites is accomplished through multiple, volatile, and often simultaneous strategies. Elites representing large and stronger groups tend to have an imbalanced share of allocated positions, and have more volatile appointments compared to groups of smaller sizes.Footnote 54

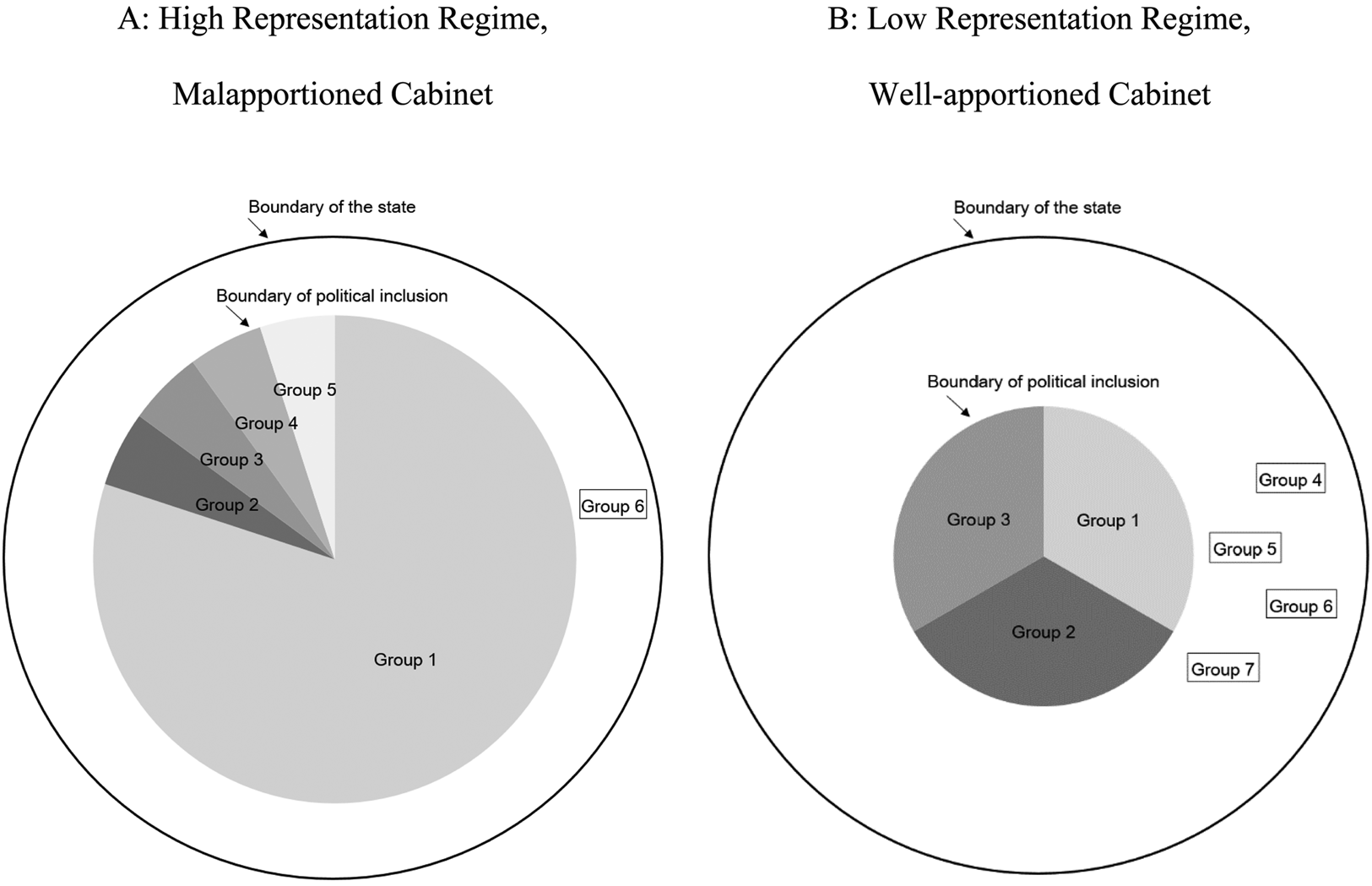

Figure 1 is a graphical illustration of two hypothetical configurations of a state with multiple ethnic groups of relatively equal size. Figure 1A represents an ethnically inclusive regime, where most ethnic groups, except one (Group 6), are included within government. Yet, this regime has a malapportioned cabinet, where Group 1 holds dominant power. Tanzanian coalitions represent this model: Tanzania has more than 120 distinct ethno-regional groups and a reputation of ethnically inclusive governance; yet, in some periods, members of Chagga and Hehe groups have taken up almost half of cabinet minister posts between them. This allows leaders to claim widespread representation, while manipulating the power distribution to sustain the regime. By contrast, Figure 1B represents an ethnically exclusive regime, where Groups 4–7 are excluded from participation in central government. It has a well-apportioned cabinet, where three included ethnic groups equally divide executive power positions. Here, representation is manipulated to the needs of powerful social groups and elites.Footnote 55 Both examples are common results of different accommodation strategies practiced between regimes and elites. Both scenarios suggest a more complex representation calculus underlying African political systems, with distinct results for elite competition.

Figure 1. Ethno-political configurations of the state.

Notes: Solid circle represents the territorial boundary of the state. Shaded circle represents the boundary and size of political representation. Each segment within the shaded circle represents the proportion of cabinet positions held by an ethnic group.

In short, there are many aspects of political survival that require manipulation at the senior scaleFootnote 56 and result in inclusive coalitions that are neither fair nor balanced. Consequently, African regimes are inclusive, unbalanced power systems where a skewed distribution of positions and material benefits is accrued by the leader and select benefactors. The effect is to stabilise the regime through promoting and rewarding transactional power politics.Footnote 57 Multiple, concurrent practices are at play at the senior level to assure leader survival and opponent suppression: strong elites may be integrated but sidelined, cabinet sizes may grow to dilute the effect of strong ministers, multiple ministries for the same issue may occur, etc. These practices can result in the skewed distribution of material benefits to a combination of groups.Footnote 58

Specific institutional arrangements, including the number of elites, groups, and the composition of coalitions that sustain a regime, produce variable degrees of political competition, representation, and stability in African politics. As leaders selectively accommodate and co-opt elites through the appointment process, more subnational bargaining, competition, and fragmentation occurs over access to state power and resources.Footnote 59

Explaining how politics and political violence are connected

Domestic power distributions create variable threats to regimes and distinct logics for political violence. High representation rates should decrease violence against the state, but high malapportionment rates should increase violence against both the state and other powerful elites and groups as they compete with each other. The underlying emphasis in this set of arguments is that the powerful – not the powerless – engage in violence. Acquiring, keeping, and consolidating power and positions are the motivations for political violence in a regime characterised by inclusivity and competitive clientelism.

Current conflict research is often predicated on an assumption that violence against the state comes from groups excluded from senior positions, and marginalised groups are three times more likely to rebel than do included groups.Footnote 60 Further, relatively wealthy or poor excluded groups are more likely to engage in armed conflict than are those of average wealth.Footnote 61 Anti-state violence is indeed most common in governments characterised by widespread exclusions: rebel violence is most likely to occur in non-democratic systems with small ruling coalitions with little opportunity to politically engage, where armed rebellion presents a legitimate and necessary strategy to overthrow regimes.Footnote 62 Taken together, these studies indicate that ethnic exclusion increases the likelihood of violence motivated by removing the executive and recasting power distributions. By taking advantage of a grievance motivation, excluded groups mobilise to challenge the incumbent and ultimately redress their political status. As enduring proof of this causal relationship, increasing representation across groups should lead to a decrease in this form of political violence. This leads to the first hypothesis:

H1: Higher levels of ethnic representation in senior government positions will decrease levels of anti-state violence.

We argue that high representation levels create alternative logics and forms of political violence. Whereas exclusive politics motivate the threat that marginalised groups present to the state, inclusive politics recasts political competition risks. For regimes, inclusion is a policy of risk management – not risk mitigation – as the composition of included elites is designed to deal with particular internal threats, such as coups,Footnote 63 electoral challenges,Footnote 64 and competition against the government. But internal power holders are still the greatest risk to leaders in autocracies or transitioning democracies,Footnote 65 and adding more elites to senior positions can exacerbate those risks by introducing competitors willing to use violence.

Competition between the powerful for access to positions is the basis for ‘inclusive conflict’. Inter-elite contestation is a likely outcome of the accommodation process within systems where political office has redistributive implications.Footnote 66 Elites may engage in violence against an opponent who is often within the same political party or identity group. They may also target state agents to influence their bargaining position for inclusion.Footnote 67 In this reading, violence is a strategy to gain and sustain leverage, and it emanates from the competition between politically viable blocs and their representatives.

Many of the determinants for positions and authority are set: elites have established community leverage, their formal power is a function of their office, and their influence is relative to others. To influence their leverage, bargaining position, claim on authority, and competitive edge, elites have incentives to design forms of violence. The outcome of competitive violence is a reordering of the elite class, and this initiates periods of bargaining. Leaders encourage a zero-sum competition between elites, and between the regime and elites, and may reward those who wield violence successfully by appointing them to more senior positions. In using violence, elites are modelling their dominance and authority over other elites, indicating how much of a potential threat they are, and securing their leverage. Even if elites using violence are not successful, there are rarely consequences for engaging in conflict, so elites can pursue those strategies with impunity. This violence is ‘costless’ to the winning elites, and a price of engagement for many other elites.

The level of competition is determined by imbalance rates among the included senior elites and groups. In an inclusive but imbalanced regime, senior elites are in competition for positions and power with leaders and with each other. Violence is expected to increase with ‘malapportionment’ of senior government positions where one, or a few groups, are dominant enough to secure more state power and resources. In some cases, underrepresented groups (that is, groups whose proportional share of cabinet positions is less than their population weight) may challenge the state through personal armies to secure greater access to government or initiate bargaining with the leader. Alternatively, over-represented groups may use violence to protect their favoured positions. In other cases, overrepresented groups and elites use violence to stifle the influence of internal competitors or other strongly represented groups.

Violence by non-state groups in aid of political elite competition is not designed to replace the leader, but can lead to the replacement of other elites. For that reason, it requires a level of precise targeting both in time and in victims. As noted in recent research about the rise and now dominance of militias in developing and democratising states, elites use these armed non-state groups to pursue violent agents and keep loose affiliations with often ethno-regionally recruited violence agents for use in specific circumstances.Footnote 68 The violence that these groups engage in can vary substantially from pitched battles between militias belonging to political elites and government agents including the president;Footnote 69 harassment of voters and other elite supporters; killing civilians in opposing communities; etc. The violence can take a myriad of forms in part because of the relationship between the elite patrons and the violent groups: these relationships are transactional,Footnote 70 intermittent, and ‘outcome focused’ in order to maximise the elite's distance and minimise their responsibility.Footnote 71 This form of conflict group and modality of violence has become dominant across Africa,Footnote 72 largely in line with changes to national level elite integration and increased competition between the powerful. This leads to the second hypothesis:

H2: Higher levels of malapportionment in senior government positions will increase the number of violent acts by non-state groups against (a) state forces and (b) other non-state armed groups.

To illustrate the real-world implications of these practices and how malapportionment is linked to conflict rather than low representation, consider examples demonstrating that some of the continent's most prolific conflicts did not emerge from exclusion, but elite-group imbalances at senior scales. In Burundi during the 1990s, the Hutu majority had representatives at the senior regime level, but the Tutsi minority (under 10 per cent of the population) elites dominated government and sought to maintain almost complete control over the regime, seats, and resources.Footnote 73 As a result of ‘elite maintenance’, a caste system developed, where violence emanated from both populations. Yet, after more than a decade of fighting, from 1993 onwards, the current government redressed the prewar political castes by introducing new, unavoidable, vulnerabilities: currently, in national and local government, seats are held by both Hutus and Tutsis with a 60–40 per cent split. This is an under-representation of the Hutu population (90 per cent of the population) and an over-representation of the Tutsis (10 per cent of the population). In part to redress their positions in power, Burundi's multiple pro-Hutu/CNDD militias operate across the state, and are linked to the interests of elites at senior levels of the government.Footnote 74

Another example is the recent rise of Ethiopian violence. For several years, Oromo militias sought to challenge their limited influence in government, and the dominance of smaller but far more powerful groups in the coalition-based system.Footnote 75 The Oromo are Ethiopia's largest group, and before the ascension of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in 2018, their political influence was muted. Armed groups claiming to be representing this community engaged consistently with the government, as did widespread demonstrators throughout 2014–17. The smaller Tigrayan and Amhara groups had significant powers and senior positions in the regime and its military apparatus since 1991, yet the influence of both groups decreased as Oromo political figures and security personnel – as well as representatives from the remaining groups in Ethiopia's federation – began to populate the senior scales. In response to these groups experiencing a decrease in power to largely proportional levels, an attempted coup in 2019 was led by Amhara members of the Ethiopian government, and Tigrayan based violence occurred in late 2020 as that minority contested their level of influence in the regime (ACLED, 2019).

Research design

Assessing elite power and distributions

Previous attempts to capture African representation have relied on lists of ethnic communities and their demographic size, expert opinion on aggregated group roles in government,Footnote 76 linguistic group numbers,Footnote 77 and distinctions on the scale of political group identity.Footnote 78 No data measured representation for a defined scale of formal, dynamic power such as the executive or legislative branches. Recently, scholars amassed cabinet data for consistent and transparent representation information as ‘a cabinet minister in Africa is considered ‘a kind of super representative’Footnote 79 expected to speak for the ‘interests of co-ethnics as well as channel resources to them’.Footnote 80 Cabinets are the locus of political decision-making and patronage opportunities from which the public may gain benefits. Appointments are a public commitment, as a minister's identity is usually open knowledge,Footnote 81 and the positions indicate the leader and elites’ ability to represent and deliver for alliances.Footnote 82 Cabinets suggest executive representation decisions because ministers are a collection of constituency representatives whose inclusion is deemed necessary for the continuation of the regime.Footnote 83 As key strategic transactions, ‘incumbents co-opt “big men”, the influential politicians who can activate their own personalized patron-client networks to recruit supporters or deliver votes on behalf of government’.Footnote 84

Ministerial positions also serve as an important means through which to forge an intra-elite bargain shaped as the leader determines necessary.Footnote 85 In short, cabinet positions are designated by the leader and serve as a direct, identifiable manifestation of accommodation and negotiation politics for elites who, in turn, offer a bridge between regimes and groups. Cabinet positions and ministers are not the sole way in which representation can be measured, but it stands as one of the most comprehensive measures of formal political power ascribed to groups and interests.

The size of cabinet and composition of positions reflects the heterogeneity of the state, and can be a gauge of relationships between leader, elites, and groups. Appointments are a far more accurate valuation of authority and power, because they provide an absolute and relative assessment of each elite and group's definite presence and political ‘weight’ in government. Appointments can identify which people and groups have inner circle or continuously stable positions and which are in the peripheral positions of great volatility. Rather than relying on an impression or illusion of group power, appointments can confirm how groups or regions are ‘relevant’ in a political environment. By using individuals and tying their presence and position to the locations and ethnic groups to which they belong, the level of representation at both group and geographic levels, simultaneously and dynamically, is a direct measure of elite power distribution over time.

ACPED

ACPED tracks the presence, position, and demographics of ministers within African cabinets for each month from 1997 to the present.Footnote 86 Each minister has a position in a state cabinet at some point from January 1997 onwards, and is included for the duration of his or her tenure. Each minister's entry has associated information including position(s), status, gender, political party, and ethno-regional background. Party affiliation indicates the political party or group of a minister; ministers with no political affiliation are recorded as ‘civil society’. Affiliations may vary over the course of tenure. All data assume that cabinet officers at the national level who claim a party membership, group, and region are representatives of those communities. There is no presumed direct effect of ministerial appointments to citizens and guaranteed return for cabinet representation. These data are a disaggregated, time varying, formalised measure of group representation, as African political regimes are a calculated balancing act by the leader and senior elites.

Representation and malapportionment indices

We use ACPED to create monthly representation and malapportionment assessments for the following states during the period 1997–2016: Algeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.Footnote 87 This sample of 15 African states represents a range of regions, violence rates, and types and ultimately, the continent at large. These countries are neither full-scale democracies nor complete autocracies; they hold elections on a regular basis without massive fraud or intimidation, although democratic procedures are often constrained by abuse of state power (for example, biased media coverage, bribery, harassment of opposition politicians, etc.).Footnote 88 Our argument stipulates that African governance challenges are arising in competitive autocracies and hybrid regimes; the variation in both the type and scale of inclusion and the absence or presence of conflict makes this sample of states a robust test of the hypotheses.

Measure of Representation

ACPED's representation score compares the aggregated elite composition in cabinet to the ethnic composition of the state.Footnote 89 The representation of a group is measured by the presence or absence of an associated cabinet minister at a given time. Ethno-political groups are identified in an ethnic macro-roster for each state, composed from several sources, including national experts, James R. Scarritt and Shaheen Mozaffar's (1999) list, Ethnologue, and Lars-Erik Cederman, Andreas Wimmer, and Brian Min's (2010) Ethnic Power Relations (EPR) data. Multiple sources reflect the variety of subnational identities that may be politically relevant in states at different time periods. Expert opinion is privileged if a discrepancy between source materials arises. Cabinet ministers are associated with their ethno-political groups. Communities who have a representative through one or more cabinet positions in a given country-month are recorded as ‘represented’ for the period of appointment(s). The aggregated monthly share of included group populationsFootnote 90 is the representation score, summarised by the following notation:

‘Representation’ for state c at time t is the combined population share (y) of represented ethnic groups i. The Representation index varies between 0 and 1; values near 0 denote high exclusivity, and values near to 1 indicate all ethno-political groups are represented in the cabinet.

Measure of malapportionment

ACPED's malapportionment measure calculates how cabinet appointments are distributed only among those groups in cabinet. The malapportionment index is calculated using the represented groups in a given state-month, and therefore, it describes how power is distributed across cabinet members. To create this measure, all the identified ethno-regional groups represented by ministers within the cabinet-month are merged with their corresponding ethno-political characteristics.

This measure of malapportionment in the national cabinet is based on previously established methods.Footnote 91 Studies on the electoral system have employed ‘disproportionality’ measures for describing the deviations resulting from the difference between party votes share and party seats share and other contexts.Footnote 92 ACPED's malapportionment score is a modified version of the ‘disproportion’ index, popularised by John Loosemore and Victor HanbyFootnote 93 and Michael Gallagher.Footnote 94 It determines the discrepancy between the shares of cabinet positions and the shares of population held by included ethnic groups. Thus, the formula becomes:

The malapportionment measure for state c at time t is computed as the summation across all ethnic groups of the difference between x, which is the share of the cabinet positions allocated to group i, and y, which is the share of the population of group i in the total population. The above index ranges between 0 and 1, where 0 denotes a perfectly-apportioned cabinet where the demographic weight of an ethnic group is matched to held seats out of the total size in cabinet, and 1 denotes a highly malapportioned case as one or more groups hold many more positions than their relative demographic weight suggests they should.

Sources of malapportionment

Lastly, to present a more nuanced picture, we identify potential sources of malapportionment. Based on the relative share of the population and cabinet representation for included groups, we distinguish between four conditions that can contribute, individually or in combination, to high levels of malapportionment:

- Majority group / Underrepresented: A politically relevant majority group that comprises more than 50 per cent of the total population and whose cabinet seat assignments are more than 50 per cent below expected proportion based on demographic size.

- Large group / Underrepresented: A group that comprises between 25–50 per cent of the population and whose cabinet seat assignments are more than 50 per cent below expected proportion based on demographic size.

- Small group / Overrepresented: A group that comprises between 5–10 per cent of the population and whose cabinet seat assignments are more than 50 per cent above expected proportion based on demographic size.

- Very small group / Overrepresented: A group that comprises less than 5 per cent of the population and whose cabinet seat assignments are more than 50 per cent above expected proportion based on demographic size.

We create four binary indicators that take the value of 1 if a cabinet in a given month has a specific condition of malapportionment – Majority Under, Large Under, Small Over, or Very Small Over – and 0 otherwise.

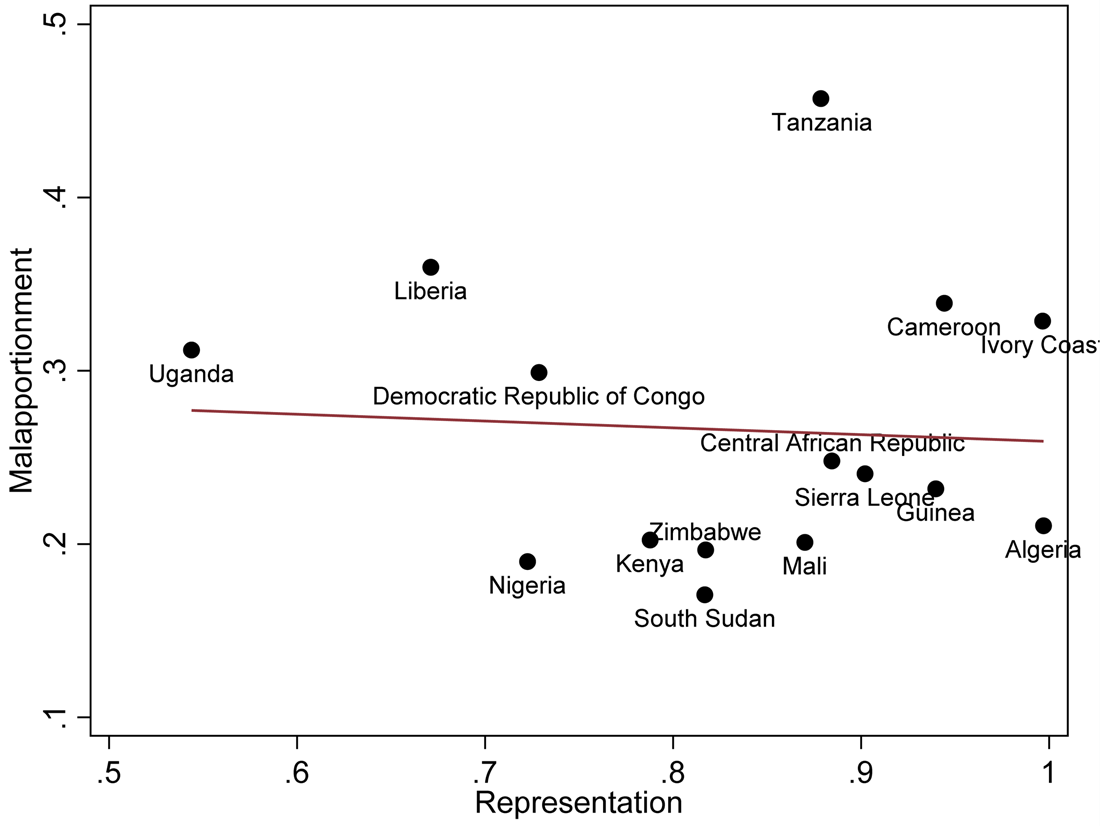

Figure 2 offers a detailed picture of the cross-country variation of representation and malapportionment scores by state. Observations located in the bottom-right part of the graph include states characterised by high levels of inclusion and well-apportioned cabinets (low malapportionment). These cases are a contrast to those in the upper left quadrant (for example, Uganda and Liberia), which exclude some segments of their ethnic population and have higher levels of malapportionment. Moving towards the upper right are states with both high representation and malapportionment levels. States such as Tanzania, Cameroon, and Ivory Coast include most ethno-political groups but distort elite power through allocating more positions to some group representatives over others. Most African states are in the bottom right-hand position, indicating that they are inclusive and allocate power proportionally across elites. Yet, there is significant variation over time even within these relatively inclusive, balanced cases. Finally, the Pearson Correlation coefficient between Representation and Malapportionment is not high (-0.163), suggesting that these two measures are not mechanically related to each other.

Figure 2. Ethnic measures of Representation and Malapportionment.

Notes: Figure 2 displays the average levels of ethnic representation and malapportionment indexes at state level computed using ACPED. All the values are computed for the period 1997–2016, except for South Sudan (2011–16).

Remaining model specifications

This study uses country-months as the unit of analysis. The conflict data come from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED)Footnote 95 whose political conflict data are distinguished by event characteristics and group(s) participating, with geographical location and date. The dependent variables are the number of conflict events for two distinct types of violence: (1) non-state armed group (rebels or militias) against the state; (2) non-state group against another non-state group. ACLED is the sole conflict data project that allows multiple interactive forms of political violence to be measured during and outside of typical ‘civil war’ periods in a systematic way.

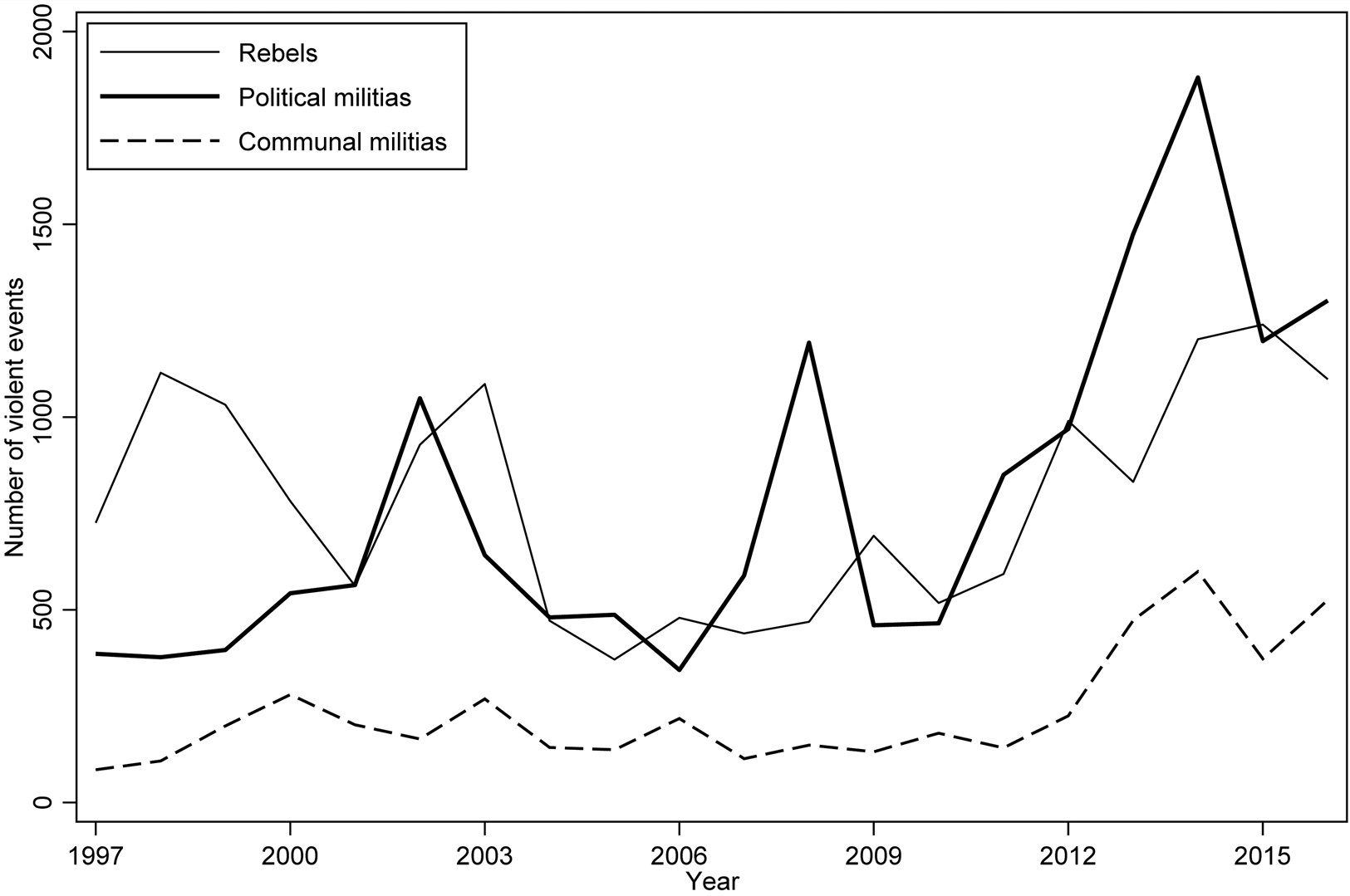

These conflict event aggregations reflect how African conflict has shifted significantly in recent years. Figure 3 displays the number of violent events associated with three agents of violence in 15 African countries from 1997 to 2016. It shows that the number of political militia events have actually surpassed the number of rebel events since 2007, together with a rise in communal militia activities since 2012. This figure tells us that African political violence now primarily consists of clashes and attacks perpetrated by political and communal militias, rather than being characterised by civil wars fought by rebels and states. Acting as personal armies for politicians (for example, Somali regional militias), militias do not seek to replace the state, but to influence its political trajectory by intimidating voters and rival candidates during election periods (for example, Mungiki in Kenya) or challenging intra-party competitors (for example, Zimbabwean ZANU-PF activity). For this reason, the conflicts considered here focus on common agents and forms of political violence but allows for a wide consideration by using all acts involving state forces.

Figure 3. Three agents of political violence in 15 African countries, 1997–2016, based on the ACLED project.

Explanatory variables include measures of ethnic Representation and cabinet Malapportionment derived from ACPED. We also use dummy variables referring to specific conditions of malapportionment, that is, Majority Under, Large Under, Small Over, and Very Small Over. All of these variables are lagged by one month to reduce endogeneity bias, which is ensuring that there are political traits preceding the occurrence of violent events. Nevertheless, we remain concerned that our results might be driven by endogeneity and reverse causality. Thus, we conducted several tests of whether past occurrences of violent events affect representation or malapportionment levels in the present month. If underrepresented groups successfully challenged the state and then attained more senior positions, we should see a decreased malapportionment (or increased representation) score. If those who challenged the state or other elites were punished by the leader, we might expect an increased malapportionment (or decreased representation) score. Neither was the case. We found no significant evidence that present values of malapportionment and representation are influenced by past conflict events.Footnote 96 One possible explanation is that the type of violence examined here – militia violence, in particular – is not designed to replace the leader, and thus is not large or intimidating enough to affect the composition of cabinets in the short term.

We include several control variables to capture factors that are known to influence conflicts through other channels. We control for the number of ministers (Cabinet Size) and discrete ethnicities represented within the cabinets (Ethnicities in Cabinet). A larger number of cabinet ministers is expected to lower the risk of internal revolt (for example, coup d’état) by making the incumbent less dependent on the loyalty of any single elite group.Footnote 97 We also expect that the number of ethnicities in cabinet may correlate with violence independent from power distributions.Footnote 98 Their inclusion enables us to identify the effects of the main explanatory variables of power distribution, while fixing the number of politicians and ethnic groups in the central government. In addition, the Democracy variable captures the quality of democracy in African states and has been found to influence the onset and degree of armed conflicts in previous research;Footnote 99 to measure this, we use the index of electoral democracy (Polyarchy index) of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project.Footnote 100 Lastly, we include the natural log of GDP per capita to control for socioeconomic conditions of the conflict state.Footnote 101 This variable is taken from the World Bank's World Development Indicators.Footnote 102

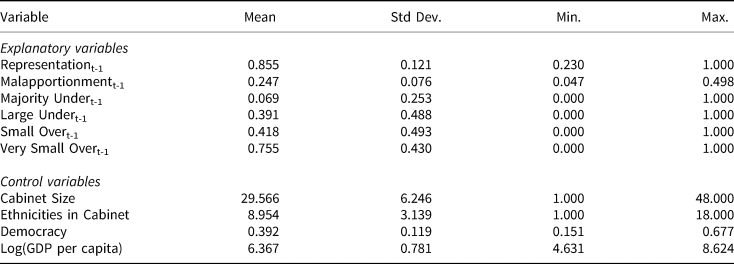

Table 1 provides summary statistics for all explanatory and control variables. The mean level of representation is 85.5 per cent, providing robust affirmation that African governments generally represent their populations. Yet, representation is volatile and varying. For example, the lowest level of representation is registered for Mali during April 2012 (8 per cent) and April 2011 (15 per cent), which preceded the onset of the civil war that affected the north of the country in 2012. The mean level of malapportionment in African cabinets is equal to 25 per cent, indicating that, on average, 25 per cent of a country's represented ethno-political population are over or underrepresented. The highest malapportionment value (49.8 per cent) of the sample is in Tanzania during August 1998.

Table 1. Summary statistics for explanatory and control variables.

A Poisson model with fixed effects tests the hypotheses and accounts for the discrete nature of the conflict variables.Footnote 103 To further control for spatiotemporal factors, we include both country and year fixed effects. Country fixed effects account for state invariant, unobserved characteristics that are likely to influence the average level of conflict within a state, such as historical grievances and geographic characteristics (for example, mountainous terrain, natural resource endowments). Year fixed effects deal with continent-wide temporal trends that may influence dependent variables (for example, drought, financial crisis). Hence, the number of violent events y ct for country c at time t is assumed to have a Poisson distribution with expectation μ ct, given a vector of explanatory and control variables ${\bf x}_{ct}$![]() , according to the following log-linear function:

, according to the following log-linear function:

where γ c and δ t are country and year fixed effects, respectively, and β is a vector of parameters to be estimated. All models are estimated with robust standard errors clustered by country.

Results on the allocation of power and conflict

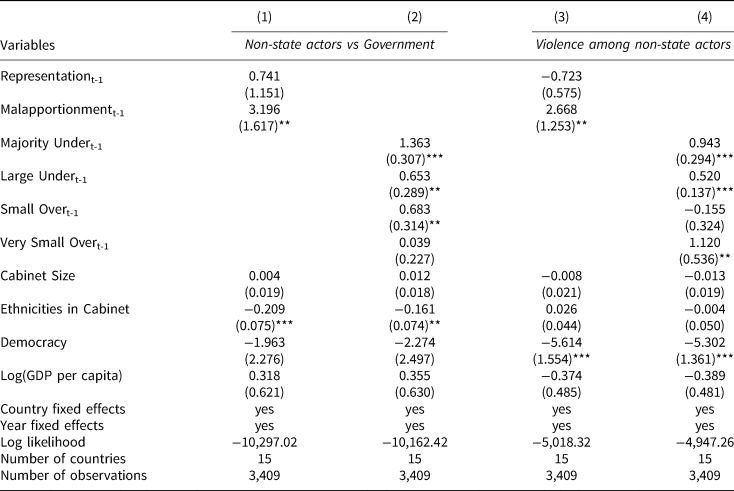

Table 2 presents coefficients and standard errors from the empirical tests of conflict events for two distinct types of violence: anti-state violence by non-state armed actors (models 1 and 2), and violence among non-state actors (models 3 and 4). In model 1, the impact of ethnic Representation on violence against the state is found insignificant, and with an unexpected positive sign. This result runs contrary to a common view among policymakers and academics that ethnicity-based exclusion from state power is a principal source of civil war (H1).Footnote 104 On the other hand, cabinet Malapportionment is a significant and strong predictor of violence against the state, lending support to H2a. When the score of Malapportionment increases from the minimum (0.047) to maximum (0.498), the number of anti-state violence increases by 323 per cent, holding other variables constant. This is consistent with our expectation that anti-state violence in hybrid regimes will increase because of elite competition or in response to the rising level of ethnic imbalance in senior government positions.

Table 2. Impact of representation and malapportionment on African political violence.

Note: Robust standard errors clustered on country in parentheses. * p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01 (two-tailed tests).

In a further effort to investigate H2a, model 2 introduces four conditions of malapportionment. According to our theory, both under- and over-represented ethnic groups spur anti-state violence: the former may challenge the state to secure greater access to government, while the latter uses violence to reinforce their favoured positions. Indeed, this is what we find. The coefficients range from a low and insignificant 0.039 for very small-overrepresented groups up to a significant 0.683 for small, overrepresented and a highly significant 1.363 for majority, underrepresented groups. The last category is especially conflict prone: having an underrepresented majority in cabinet increases the number of anti-state violence by about 286 per cent, holding other variables constant. On the other hand, a small and insignificant coefficient on Very Small Over suggests that smaller groups are less able to challenge a government due to their limited pool of resources and potential fighters. These results clearly confirm H2a but not H1: Given that African states generally practice inclusive representation today, the main factor in cross-national variation of anti-state violence is not ethnic exclusion but distorted distribution of elite power.

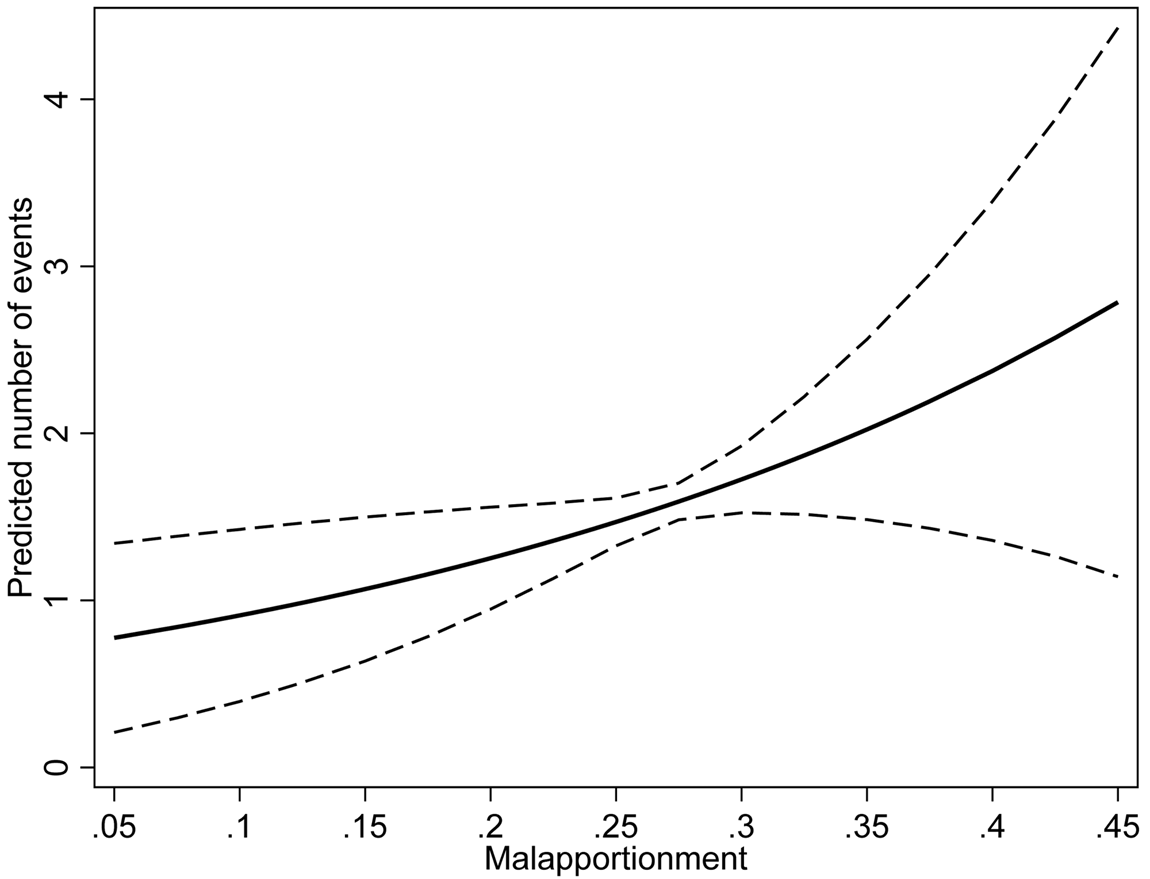

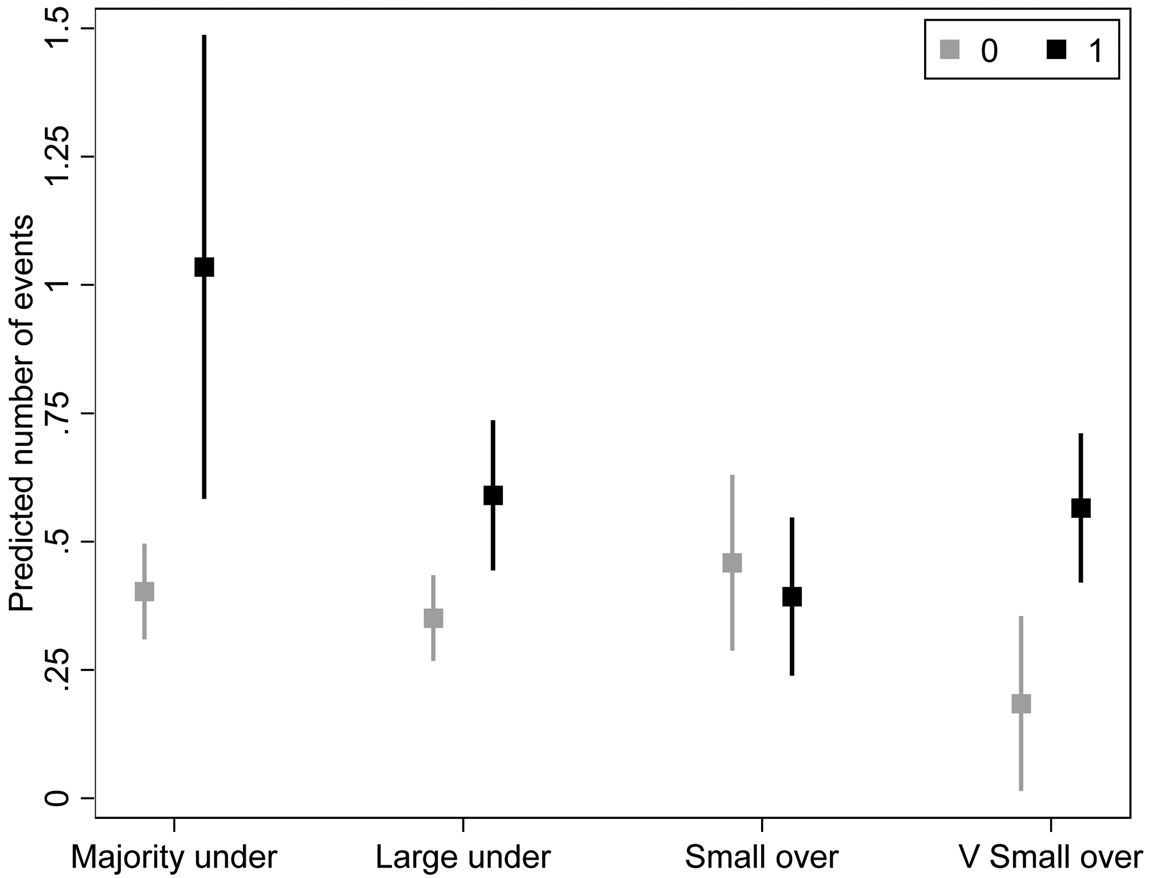

Figure 4, which is based on model 1, plots the predicted number of violent events against the state as a function of Malapportionment, holding other variables at their means. We observe a significant and positive effect of cabinet malapportionment: as the Malapportionment measure gets higher, so does the risk of anti-state violence by non-state armed groups, although the effect is imprecisely estimated for highly malapportioned cabinets. Figure 5, which is based on model 2, shows the relative differences in predicted number of anti-state violence caused by each condition of malapportionment. The effect of underrepresented majority group is most pronounced: a change in Majority Under from 0 to 1 is expected to increase number of violence by 3.9 times, holding other variables at their mean values.

Figure 4. Predicted number of violence against the state (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) as a function of Malapportionment. All other variables are held at their means.

Figure 5. Relative differences in predicted number of violence against the state (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) by four conditions of malapportionment. All other variables are held at their means.

Shifting our attention from anti-state violence to non-state infighting in model 3, the coefficient for Malapportionment is also positive and statistically significant for violence among non-state actors, providing support for H2b. Increasing the Malapportionment score from the minimum to maximum raises the expected violence among non-state actors by about 233 per cent, holding all other factors constant. On the other hand, we do not find any substantive effect of Representation. These results show violent competition among non-state actors is emerging as an alternative modality of political violence in African states, which have ethnically inclusive but malapportioned governments. In model 4, we replace aggregate indices of power distribution with specific conditions of malapportionment. Again, the presence of underrepresented majority and large ethnic groups (Major Under and Large Under) increases the number of violence between non-state groups significantly, in line with H2b. In addition, the impact of Very Small Over is both large and significant in contrast to its effect on anti-state violence in model 2, suggesting that lower mobilisation capacity does not deter violent infighting among non-state actors.

Figure 6 offers a graphical presentation of how different conditions of malapportionment influence violence among non-state actors. The plots, based on model 4, show that cabinets with an underrepresented majority remain the most fertile condition for intra-elite violence. Also noteworthy is the effect of Very Small Over, which is as large as the effect of Large Under. This analysis provides additional support for H2b. The imbalance of power between two group types generates violent competition between non-state actors: large groups with fewer seats are seeking to redress their limited leverage, while smaller groups with more seats are seeking to secure their level of power within the regime.

Figure 6. Relative differences in predicted number of violence among non-state actors (with 95 per cent confidence intervals) by four conditions of malapportionment. All other variables are held at their means.

Four conditions of malapportionment warrant further explanation. A strategic imbalance emerges when large groups are accorded representation without adequately reflecting their population share. It is often intentional: leaders have the choice to extend the size of cabinet to distribute seats in line with demographic size, or can choose to reduce the seats given to other groups, including significantly-sized groups, small, or very small politically relevant communities. Choosing not to do so reflects that a leader is actively seeking to suppress the influence of large groups, while still nominally representing said communities in cabinet. The seat(s) allocated to large groups may be of high importance, such as finance or foreign ministries. But by limiting the internal strength of a group within cabinet, leaders can suppress challenges that may arise from coordinated internal actions, or place a significant barrier to the coordinated actions across different representative elites and groups. The result is that large groups are represented but have lower levels of relative power within cabinet, and in turn this nullifies an ‘exclusion’ grievance to motivate large scale conflict against the state, while also suppressing the ability to harness internal cabinet strength to sanction or leverage against the leader. One way to redress this imbalance is to engage in conflict, at low levels, to challenge the state or other overrepresented elites, thereby increasing the ‘consequences’ of imbalance for the leader. The logic in these circumstances is that a group can raise the cost of being sidelined, over the leader's benefit for doing so.

The control variables provide additional insights. Higher numbers of ethnic groups in cabinet (Ethnicities in Cabinet) significantly decreases violence against the state. This result might suggest that greater inclusivity in cabinet representation decreases the risk of armed rebellion. However, ethnically diverse cabinets are not necessarily inclusive, so the results on the number of ethnicities in cabinet do not provide solid evidence for H1.Footnote 105 In addition, higher levels of electoral Democracy have significant, negative effects on violence between non-state groups while having no significant impact on anti-state violence. Finally, Cabinet Size and GDP per capita fail to exhibit any significant or substantive effects on both types of violence.

Our main findings can be summarised as follows. First, in African polities that generally practice inclusive representation, ethnic exclusion or representation is no longer a significant predictor of anti-state violence. Second, the inequality of power between included groups, rather than ethnic exclusion, is a better predictor of which countries are at risk for political violence. This includes a malapportioned cabinet where one or a few select ethnic groups have dominant influence. Third, the risk of both anti-state violence and non-state groups’ infighting is substantially higher for malapportioned regimes where cabinet seats are under-allocated to majority or large ethnic groups.

Lastly, it is important to note that these results come with an important caveat: our efforts to capture violent competition between included elites is conducted with aggregate data at the country level. Thus, while we find that imbalanced power in cabinet has the largest effect on the number of violent events, our research design cannot rule out the possibility that some of those events were carried out by excluded groups. Ongoing research will illustrate how relative power shares are associated with intensity, modality, and frequency of violence at the subnational level.

Conclusion

The political inclusion of ethno-political groups is not an absolute solution for national grievances. Violence is used by included groups and elites to assert their control of the state, and this reinforces that groups in power, rather than out of power, have significant influence on levels of conflict in African countries. Therefore, beyond the knowledge that excluded groups are more likely to rebel, those with state power must be considered when explaining political violence. Domestic politics generates the motivation, agents, and dynamics of political violence, and how leaders manage competing political identities underlies the success or failure of government functions.Footnote 106 As political institutions have changed across Africa, the strategic calculations of leaders and subnational elites have changed to reflect the political contests in new institutions. In turn, conflict has adapted, changing form to fit into the present power contest.

We also argue that the link between conflict and representation has been unduly limited to exclusion and civil wars. But other modalities of political violence have increased, while political inclusion has risen. We find that political violence is widespread across democratising states because of ‘competitive clientelism’, where elites are vying for senior positions and leaders are seeking to build inclusive ruling coalitions, violence becomes a strategy of negotiation. Organised violence becomes a strategy of elites to increase power, and is directed against regimes and other elites. In competitive clientelism, violent strategies are closely associated with included elites rather than marginalised communities. Pursuing armed, organised violence is a strategy of those with the means and ability to generate significant pressure on the regime; excluded groups are limited in their capacity to pursue this option. The contest for power takes place among elite members of an inclusive ruling coalition. To that end, conflict is not due to a breakdown in competitive clientelism: it is often a feature of it.

These findings suggest that power politics, or ‘realpolitik’ principles, are apt representations of elite competition across African states. Leaders are engaged in a two-level game: they will appoint elites to the cabinet from a large swathe of the population, maximising ‘representation’ and ‘inclusivity’ and providing enough rents and positions to potential spoilers. This is necessary for legitimacy, consolidation of authority, and influence across the state. Nevertheless, higher levels of malapportionment in the national cabinet can still increase the risk of violence against the state. ‘Dissatisfied’ elites may engage in anti-state violence for greater access to state power and resources. Therefore, imbalance in elite representation creates conflict, but rarely challenges leaders.

To conclude, a leader's survival is closely dependent on co-opted subnational elites, but a leader's optimal coalition is not necessarily one that is fairly balanced. Strategies employed to generate a compliant coalition are not likely to be stable or peaceful. Regimes across African states have managed to include great numbers of ethno-political communities, expand and retract cabinets frequently, and withstand variable levels and modalities of political violence, both against the state and between elites. These factors underscore that competitive clientelism is a core feature of African politics. Further, it reinforces the importance of subnational elites as critical political figures within African politics and as objects of study among scholars seeking to understand the changing dynamics of violence across the continent.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Horizon 2020 European Research council via Clionadh Raleigh's ERC ‘Consolidator’ grant. Dr Guiseppe Maggio was central to determining many of the measures for cabinet representation levels, and Stephen Hunt assisted with the final proofs of this article. This research was funded by the Horizon 2020 European Research Council Grant No. 726504 (VERSUS).

Supplementary material

To view the online supplementary material, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210521000218