1. Introduction

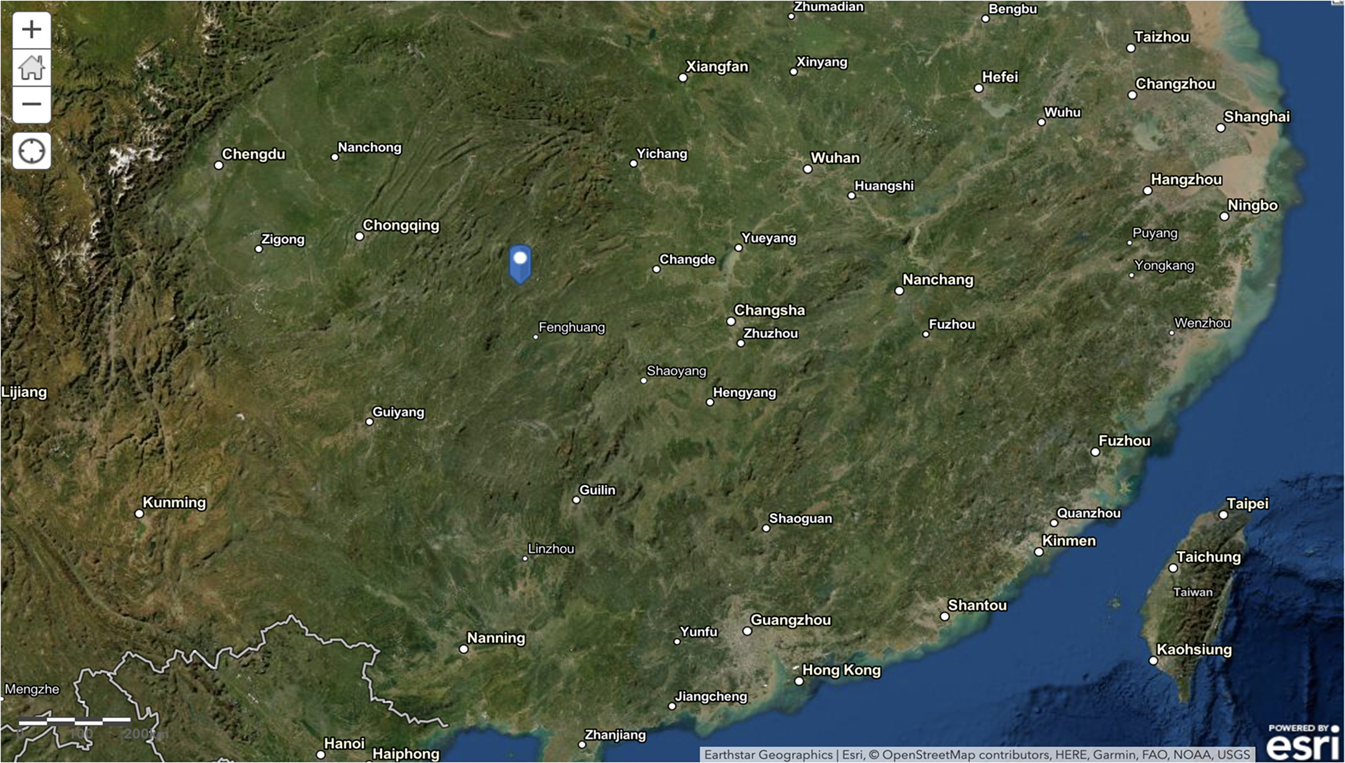

In July 2002, more than 37,000 bamboo and wooden slips were found in the old well in Liye Gucheng 里耶古城 in Longshan County 龍山, Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture 湘西土家族苗族自治州, Hunan Province 湖南省 (see Figure 1).Footnote 1

Figure 1. Liye Gucheng 里耶古城

These slips belong to the so-called Qin Slips 秦簡 and are known as the Liye Qin Slips 里耶秦簡 (Liye Qinjian). They cover a wide range of topics, including legal documents, the administration of the commandery 郡 jùn, and the grain supply system before and after the Qin dynasty.Footnote 2 According to philologists who have studied the Liye Qin Slips, since Liye used to be within the state of Chu 楚地, some slips reflect the influence of the writing system of the Chu State in the Warring States period.Footnote 3 Regarding the scribes of the Liye Qin Slips, there must have been several writers.Footnote 4

The Liye Qin Slips include references to several kinds of grain, including 粟米 sùmǐ “millet”, 稻 dào “rice (or rice plant)”, 需(糯)米 nuòmǐ “glutinous rice”, 秫 shù “glutinous millet”, and 麥 mài “wheat”. Note that among these grains, 粟米 sùmǐ “millet” appears most frequently, followed by 稻 dào “rice (or rice plant)”.Footnote 5 Other grains only appear a few times in the Liye Qin Slips. This distribution indicates that “millet” and “rice” were the main staples in the Liye district. Although the character 稻 dào refers to the rice plant in Classical Chinese texts, Chen Wei (Reference Chen2012: 30) noted that 稻 dào means “unhusked rice 稻穀”, while Huang Haobo (Reference Huang2015: 126) regarded it as “husked rice 稻米” based on the study of the conversion rate of 稻 dào in the Liye Qin Slips,Footnote 6 and this latter interpretation appears to be most likely.

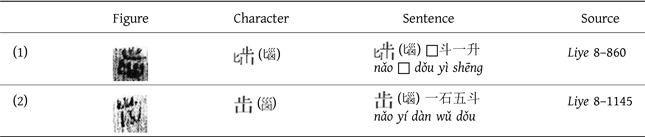

Aside from these four types of grain, there are other characters representing grain: ![]() nǎo and

nǎo and ![]() nǎo. These characters appear once with a record of the amount on the slips (see Table 1).

nǎo. These characters appear once with a record of the amount on the slips (see Table 1).

Table 1. ![]() nǎo and

nǎo and ![]() nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips

nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips

The purpose of this article is to trace the history of the character ![]() nǎo and discuss the word for “rice” in Old Chinese (hereafter OC) and Hmongic before and after the Qin dynasty. As mentioned, “millet” and “rice” appear most frequently in the Liye Qin Slips, so the character

nǎo and discuss the word for “rice” in Old Chinese (hereafter OC) and Hmongic before and after the Qin dynasty. As mentioned, “millet” and “rice” appear most frequently in the Liye Qin Slips, so the character ![]() nǎo probably represents one of them.

nǎo probably represents one of them.

The following sections will mainly focus on the character ![]() nǎo and related characters seen in the Liye Qin Slips and seek to determine what the character

nǎo and related characters seen in the Liye Qin Slips and seek to determine what the character ![]() nǎo represents.

nǎo represents.

2. The character  nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips

nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips

2.1. The characters  nǎo and

nǎo and  nǎo

nǎo

The characters ![]() nǎo and

nǎo and ![]() nǎo each appear once on the Liye Qin Slips; see (1) and (2) in Table 1.

nǎo each appear once on the Liye Qin Slips; see (1) and (2) in Table 1.

The two figures in (1) and (2) were converted into the modern characters ![]() nǎo and

nǎo and ![]() nǎo, which are composed of 匕 bǐ, 止 zhǐ, and 山 shān (the latter is composed of 止 zhǐ and 山 shān). It is generally agreed that these two characters are variants of the characters 匘 nǎo and

nǎo, which are composed of 匕 bǐ, 止 zhǐ, and 山 shān (the latter is composed of 止 zhǐ and 山 shān). It is generally agreed that these two characters are variants of the characters 匘 nǎo and ![]() nǎo.

nǎo.

According to the annotator of the Liye Qin Slips, the character 匘 nǎo should be read as the word “glutinous rice, 稬 nuò” by phonetic loan, as the word 稬 nuò means “rice (or rice plant), 稻 dào” in the Pei state 沛國; therefore, the character 匘 nǎo here might represent the word “rice, 稻 dào”.Footnote 7

However, the characters 匘 nǎo and 稬 nuò are not interchangeable by phonetic loan. 匘 nǎo came from *-u (or *-aw) in OC, and 稬 nuò descended from *-or (or *-oj). Therefore, it is unlikely that the character 匘 nǎo represents the word 稬 nuò “glutinous rice” here; see Table 2.Footnote 8

Table 2. Reconstruction compared: 匘 nǎo, 稬 nuò, and 稻 dào

While 匘 nǎo and 稻 dào bear the same vowel *-uʔ with the same tone category, they do have different initials *n- and *l-. For this reason, 匘 nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips does not represent the word “rice, 稻 dào” directly.Footnote 9

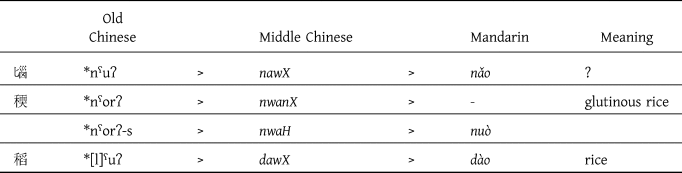

In addition, since the character 稻 dào itself appears in the Liye Qin Slips, it does not seem that 匘 nǎo and 稻 dào represent the same word, as seen in Table 3.

Table 3. 稻 dào in the Liye Qin Slips

It is possible that 稻 dào is a standard form for “rice”, while 匘 nǎo is a substratum form (local languages).

In what follows, we will examine related characters to confirm the reconstructed form of ![]() (匘) nǎo.

(匘) nǎo.

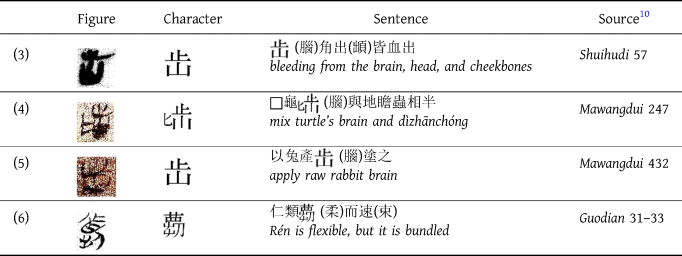

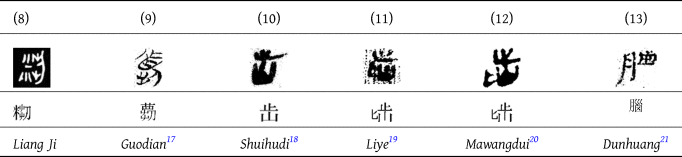

2.2. Related characters in other excavated documents

In addition to the Liye Qin Slips, related texts with ![]() (匘) nǎo appeared in other excavated documents (see Table 4).

(匘) nǎo appeared in other excavated documents (see Table 4).

Table 4. Related characters

As seen in Table 4, the characters ![]() nǎo and

nǎo and ![]() nǎo represent the word for “brain, 腦 nǎo” in (3), (4), and (5).Footnote 11 The character

nǎo represent the word for “brain, 腦 nǎo” in (3), (4), and (5).Footnote 11 The character ![]() in (6) represents the word for 柔 rǒu, meaning “supple, soft, and flexible”. As 柔 rǒu unambiguously came from OC *nuʔ according to rhyme evidence,Footnote 12

in (6) represents the word for 柔 rǒu, meaning “supple, soft, and flexible”. As 柔 rǒu unambiguously came from OC *nuʔ according to rhyme evidence,Footnote 12 ![]() is *nuʔ (or *nˤuʔ) as well. As discussed below (§2.3), the bottom part of the character

is *nuʔ (or *nˤuʔ) as well. As discussed below (§2.3), the bottom part of the character ![]() , which is

, which is ![]() , is the phonetic element. Note that the character

, is the phonetic element. Note that the character ![]() nǎo is considered a variant of

nǎo is considered a variant of ![]() (see §2.3 for details). Based on these phonetic loans, the character

(see §2.3 for details). Based on these phonetic loans, the character ![]() nǎo and 腦 nǎo simultaneously can be reconstructed as *nˤuʔ in OC.Footnote 13 See the reconstructed form in Table 5.

nǎo and 腦 nǎo simultaneously can be reconstructed as *nˤuʔ in OC.Footnote 13 See the reconstructed form in Table 5.

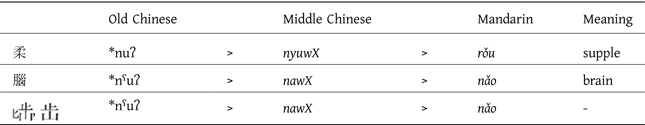

Table 5. The reconstructions compared: 柔, 腦, and ![]() (

(![]() )

)

2.3. The development of the character  (匘) nǎo and its phonetic element

(匘) nǎo and its phonetic element

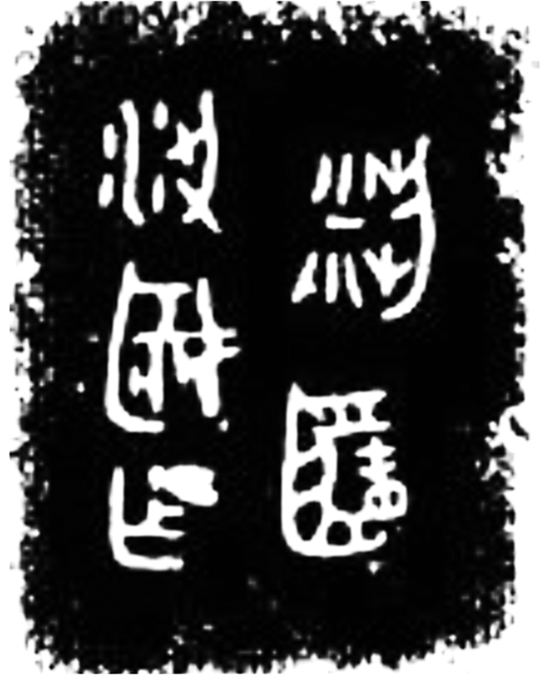

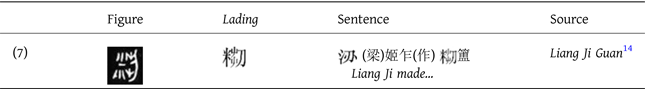

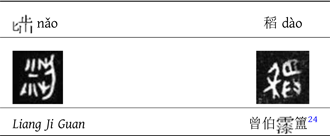

In addition to the Liye Qin Slips, Chen Jian (Reference Chen2008/2019) provided another document that records a character related to ![]() nǎo in the Western Zhou Bronze scripts (dated at the latest to the late Western Zhou);Footnote 15 see Figure 2 and Table 6.

nǎo in the Western Zhou Bronze scripts (dated at the latest to the late Western Zhou);Footnote 15 see Figure 2 and Table 6.

Figure 2. Liang Ji Guan 梁姬罐 (Tomb M2012 of Guo State 虢国墓地 M2012)

Table 6. The character ![]() in the late Western Zhou bronze scripts

in the late Western Zhou bronze scripts

The character in (7) is composed of the elements 米 mǐ, 艸 cǎo, and 刀 dāo. The original annotator of Liang Ji Guan pointed out that the right-hand element of the character (艸 cǎo and 刀 dāo) is a pictograph meaning the act of “cutting the grass with a knife”.Footnote 16 Notably, Chen Jian (Reference Chen2008/2019: 97–105) presented a hypothesis that the character ![]() in (7) is an antecedent of the character

in (7) is an antecedent of the character ![]() nǎo. The transformation of the shape from

nǎo. The transformation of the shape from ![]() to 腦 nǎo is summarized in Table 7.

to 腦 nǎo is summarized in Table 7.

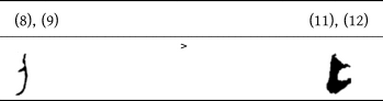

Table 7. The transformation of the character 腦 nǎo

The middle part of the character ![]() in (8) has transformed to

in (8) has transformed to  in (9) and to

in (9) and to  in (10), (11), and (12). These characters seem to have been transformed to 止 zhǐ or 山 shān in the Qin and the early Han dynasties. Finally, the character

in (10), (11), and (12). These characters seem to have been transformed to 止 zhǐ or 山 shān in the Qin and the early Han dynasties. Finally, the character ![]() nǎo is transformed to

nǎo is transformed to  , as shown in (13); see Table 8.

, as shown in (13); see Table 8.

Table 8. The development of the parts of ![]() nǎo

nǎo

In addition, the characters 刀 dāo in (8) and (9) are replaced by 匕 bǐ in (11) and (12); see Table 9.

Table 9. The change from 刀 dāo to 匕 bǐ

Since the characters ![]() nǎo and

nǎo and ![]() nǎo almost always represent the word for “brain”, the semantic unit “肉 (月)” might have been added instead of “匕” as in (13).

nǎo almost always represent the word for “brain”, the semantic unit “肉 (月)” might have been added instead of “匕” as in (13).

As seen in the contexts in (1) and (2), it is generally agreed that ![]() nǎo represents a kind of grain; however, what kind of grain it stands for precisely remains unclear. The shapes of the characters might be key to determining their evolution. The character

nǎo represents a kind of grain; however, what kind of grain it stands for precisely remains unclear. The shapes of the characters might be key to determining their evolution. The character ![]() nǎo was regarded as a pictograph meaning the act of “cutting the grass with a knife”. If true, the character

nǎo was regarded as a pictograph meaning the act of “cutting the grass with a knife”. If true, the character ![]() nǎo might originally have represented the word “cutting the rice plant” or the noun “rice plant” and then changed so that it could also represent “husked rice” and “unhusked rice” at the latest shortly before or after the Qin dynasty.

nǎo might originally have represented the word “cutting the rice plant” or the noun “rice plant” and then changed so that it could also represent “husked rice” and “unhusked rice” at the latest shortly before or after the Qin dynasty.

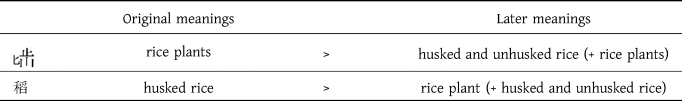

In contrast, the components of the character 稻 dào, as Sagart (Reference Sagart2011: 128) has argued, have the meaning of “dehusked rice grains out of the mortar”.Footnote 22 Compare the characters shown in Table 10.

Table 10. ![]() nǎo and 稻 dào

nǎo and 稻 dào

According to the components, the former probably initially meant “rice plant” and the latter “husked rice (or its process)”. The character 稻 dào initially referred to “husked rice” and changed so that it could also represent “rice plant” at a later stage.

Table 11. Semantic changes

In section 3, we examine the word “稻 dào” in OC and the Hmong-Mien languages (hereafter HM).

3. 稻 “Rice or rice plant” in Old Chinese and Hmong-Mien

3.1. 稻 Dào in OC

稻 Dào is reconstructed as *[l]ˤuʔ based on the rhyme evidence in the texts of the Shījīng and Xiéshēng connections.Footnote 23

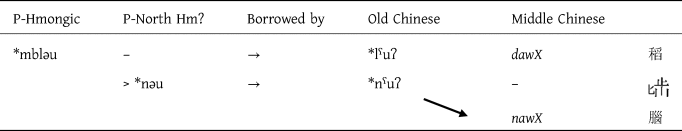

Previous studies considered the Chinese word for “rice (or rice plant), 稻 dào” to be a loan word from HM. For example, Haudricourt and Strecker (Reference Haudricourt and Strecker1991: 335–41) expected that agricultural words were borrowed from HM and that “husked rice” was one of them.Footnote 25 Haudricourt and Strecker regard these words as HM substrata in Chinese. Ratliff (Reference Ratliff2018: 131–2) adduced three reasons why rice is regarded as a loan from HM into Chinese: (1) “… the archeological record shows that rice cultivation occurred in the south before it was known to the ancient Chinese,Footnote 26 who cultivated millet, and that the ancestors of the Hmong-Mien people were in the right location to have been the first rice cultivators”;Footnote 27 (2) “… there is no evidence of an initial nasal in Old Chinese”; and (3) “… the word does not appear in Tibeto-Burman”. There is no internal evidence for rice (or rice plant) to reconstruct the prenasalized obstruent in Chinese. Hence, it is highly probable that the Chinese language adopted the word “rice (or rice plant)” from Proto-HM.Footnote 28 However, the tone is irregular; the OC Shǎngshēng (rising tone) tone typically corresponds to Tone B in HM.Footnote 29

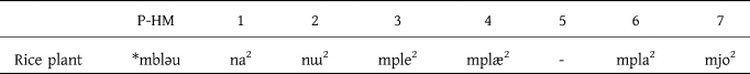

Table 12 shows the “rice plant” data for Hmongic languages.Footnote 30 As demonstrated, the proto-form of onsets for “rice plant” is reconstructed as *mbl- based on the data.Footnote 31

Table 12. “Rice plant” data in Hmongic, from Ratliff Reference Ratliff2010: 48Footnote 32

If “rice (or rice plant), 稻 dào” is a loanword from HM, it is assumed that the prenasalized obstruent was dropped and simplified to *[l]ˤ- when the ancient Chinese people borrowed it (*mbl- > *[l]ˤ-).

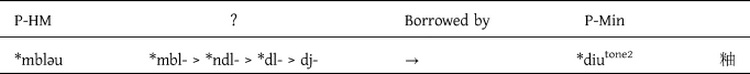

Notably, the word for “rice plant” in Proto-Min (hereafter P-Min) is reconstructed as *diutone2 粙. P-Min Tone 2 corresponds with OC Shǎngshēng, with no problem with tonal correspondences. The problem is that the P-Min form has a semivowel -i-, whereas the MC 稻 dào belongs to division 1, which does not reflect -i-. The semivowel -i- in Min might have come from *dl- within certain stages of P-HM as follows: *mbl- > *ndl- > *dl- > *dj- (P-Min *diutone2).Footnote 33 The semivowel *-i- indicates that P-Min might have borrowed the word “rice plant” from a different stratum with OC and that the word for “rice (rice plant)” was borrowed from HM.

3.2. The distribution of “rice plant” among the Hmongic languages

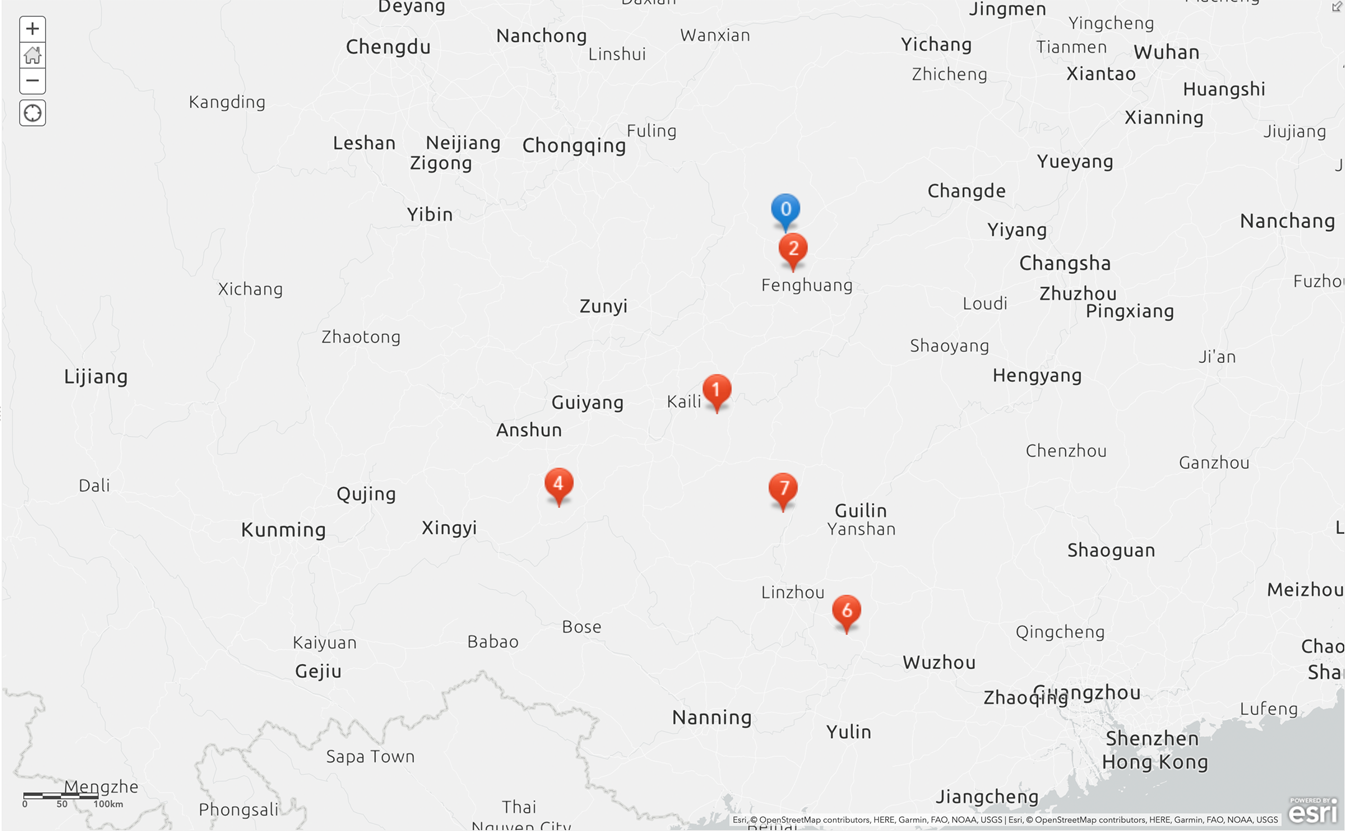

The data from Table 12 are converted into Figure 3. This map shows minimal data only.Footnote 34

Figure 3. “Rice plant” in Hmongic

In the southern parts (places 4 and 6), prenasalized clusters remain (*mbl- > mpl-), while in East Hmongic and North Hmongic (places 1 and 2), the dental nasal *n- appears more often (*mbl- > n-).Footnote 35 In addition to these data, other dialects have a prenasalized dental obstruent, such as ndl- and ntl-.Footnote 36 These data show that *mbl- had assimilated to ndl- and ntl- before the lateral *-l-.

3.3.  Nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips and “rice plant” in North Hmongic languages

Nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips and “rice plant” in North Hmongic languages

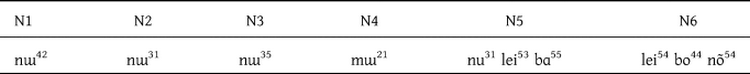

In a fascinating detail, no. 0 in Figure 3 indicates the location of Liye Gucheng where the Liye Qin Slips were unearthed. It is obviously near no. 2 “Jiwei 吉衛 (North Hmongic)” with the dental nasal *n- for onsets. The straight-line distance between Liye Gucheng and Jiwei is only 50 km. Most of the data from the North Hmongic subgroups have the nasal n- for unhusked rice (or rice plants), as shown in Table 13.

Table 13. Data from North Hmongic: unhusked riceFootnote 37

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the data from North Hmongic (no. 0 indicates the location of Liye Gucheng).

Figure 4. Rice in North Hmongic

As mentioned in §2 above, the characters ![]() nǎo and

nǎo and ![]() nǎo are reconstructed as *nˤuʔ, and this intriguingly coincides with Jiwei [nɯ2], Yangmeng [nɯ31], and Zhongxin [nɯ35]. Hence, it is assumed that the character

nǎo are reconstructed as *nˤuʔ, and this intriguingly coincides with Jiwei [nɯ2], Yangmeng [nɯ31], and Zhongxin [nɯ35]. Hence, it is assumed that the character ![]() nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips represents the same word as “rice or rice plant” in these languages. Although it is difficult to determine whose word it was originally, if this assumption holds, we can deduce that OC borrowed at least two varieties of “rice plant”: *mbləu in P-HM (or P-Hmongic) and *nəu in “Proto-North Hmongic (provisional) or certain groups of North and East Hmongic speakers”.Footnote 38 The former dropped *mb- when the Chinese borrowed it; the latter is a substratum word, and the word itself was lost in the ancestor of Middle Chinese and modern Chinese dialects (when the character

nǎo in the Liye Qin Slips represents the same word as “rice or rice plant” in these languages. Although it is difficult to determine whose word it was originally, if this assumption holds, we can deduce that OC borrowed at least two varieties of “rice plant”: *mbləu in P-HM (or P-Hmongic) and *nəu in “Proto-North Hmongic (provisional) or certain groups of North and East Hmongic speakers”.Footnote 38 The former dropped *mb- when the Chinese borrowed it; the latter is a substratum word, and the word itself was lost in the ancestor of Middle Chinese and modern Chinese dialects (when the character ![]() nǎo became used for the word “brain 腦 nǎo” instead), as shown in Table 14.

nǎo became used for the word “brain 腦 nǎo” instead), as shown in Table 14.

Table 14. The direction of loanwords: OC

As mentioned above, the P-Min “rice plant” is reconstructed as *diutone2. This could have come from the different HM dialects with OC, as shown in Table 15.

Table 15. The direction of loanwords: P-Min “rice plant”

Since the characters ![]() nǎo and

nǎo and ![]() nǎo, which initially referred to “rice or rice plant”, represent the word for “brain, 腦 nǎo” bearing the onset *nˤ- in the Qin Slips and the Mawangdui silk manuscript, we can estimate that the assimilation (*mbl- > *n-) must have taken place at the latest sometime before or after the Qin dynasty (approximately 200 K) in East and North Hmongic. Proto-Hmong-Mien might be even older.Footnote 39

nǎo, which initially referred to “rice or rice plant”, represent the word for “brain, 腦 nǎo” bearing the onset *nˤ- in the Qin Slips and the Mawangdui silk manuscript, we can estimate that the assimilation (*mbl- > *n-) must have taken place at the latest sometime before or after the Qin dynasty (approximately 200 K) in East and North Hmongic. Proto-Hmong-Mien might be even older.Footnote 39

4. Conclusion

Two kinds of grain, “millet, 粟米 sùmǐ” and “husked rice, 稻 dào”, appear most frequently in the Liye Qin Slips. In addition to these grains, another character is seen in the Liye Qin Slips: ![]() nǎo. It represents the words for “brain, 腦 nǎo” and “supple, 柔 rǒu” in other excavated documents. Since 柔 rǒu is reconstructed as *nˤuʔ based on the rhyme data, both 腦 nǎo and

nǎo. It represents the words for “brain, 腦 nǎo” and “supple, 柔 rǒu” in other excavated documents. Since 柔 rǒu is reconstructed as *nˤuʔ based on the rhyme data, both 腦 nǎo and ![]() nǎo are thought to have had the same sound at the time.

nǎo are thought to have had the same sound at the time.

The archaeological data suggest that rice cultivation occurred around the middle and lower Yangtze Valley, the homeland of Proto-HM (formerly the state of Chu 楚地). The word “rice or rice plant, 稻 dào” seems to be a loanword from HM into OC, and the “rice plant” proto-form in Hmongic is reconstructed as *mbləu (OC *lˤuʔ).

What interests us is that the proto-form of ![]() nǎo, which is *nˤuʔ, bears the same onset as the sound of “rice plant” in North and East Hmongic (n- < *mbləu). It is assumed that OC *nˤuʔ (

nǎo, which is *nˤuʔ, bears the same onset as the sound of “rice plant” in North and East Hmongic (n- < *mbləu). It is assumed that OC *nˤuʔ (![]() ) probably cognates with the word [nɯ] in these languages, and it represents the word “rice or rice plant” in the Liye Qin Slips.Footnote 40 Hence, we estimate that the assimilation (*mbl- > *n-) in certain groups of North and East Hmongic must have taken place at the latest just before or after the Qin dynasty (approximately 200 bce).Footnote 41

) probably cognates with the word [nɯ] in these languages, and it represents the word “rice or rice plant” in the Liye Qin Slips.Footnote 40 Hence, we estimate that the assimilation (*mbl- > *n-) in certain groups of North and East Hmongic must have taken place at the latest just before or after the Qin dynasty (approximately 200 bce).Footnote 41

nǎo, is thought to represent grain. It also represents the words for “brain, 腦 nǎo” in other excavated documents. Since the archaeological data show that rice cultivation was practised around the middle and lower Yangtze Valley, the homeland of Proto-Hmong Mien (formerly the state of Chu 楚地), the word for “rice plant, 稻 dào” seems to be a loanword from Proto-Hmong Mien *mbləu. The character

nǎo, is thought to represent grain. It also represents the words for “brain, 腦 nǎo” in other excavated documents. Since the archaeological data show that rice cultivation was practised around the middle and lower Yangtze Valley, the homeland of Proto-Hmong Mien (formerly the state of Chu 楚地), the word for “rice plant, 稻 dào” seems to be a loanword from Proto-Hmong Mien *mbləu. The character