Introduction

Smoking is the single most preventable cause of death, resulting in an estimated 6 million premature deaths globally per year, with the largest burden being in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (GBD Tobacco Collaborators, 2015). Stopping smoking can reduce risk of premature death and improve current and future health (Doll, Peto, Boreham, & Sutherland, Reference Doll, Peto, Boreham and Sutherland2004; USDHHS, 1990). Advice from healthcare professionals (HCPs) can be one of the most important triggers for a smoker to make a quit attempt (NHS Future Forum, 2012; Stead et al., Reference Stead, Buitrago, Preciado, Sanchez, Hartmann-Boyce and Lancaster2013). The question is how to give this advice effectively without taking up too much time or harming the relationship with patients.

The traditional approach to delivering cessation advice is to focus on informing smokers of the harms caused by smoking and advise them to stop; but recent evidence has shown that offering patients support with quitting is more effective (Aveyard, Begh, Parsons, & West, Reference Aveyard, Begh, Parsons and West2012; West & Fidler, Reference West and Fidler2011). Compared with no advice, the odds of quitting are 68% higher if stop smoking medication is offered and 217% higher with an offer of support with quitting from HCPs (Aveyard, Begh, Parsons, & West, Reference Aveyard, Begh, Parsons and West2012). In a large study across the whole of England, it was found that smokers were almost twice as likely to try to stop if they had been offered help by their general practitioner (GP), than if they had only been advised to stop smoking (West & Fidler, Reference West and Fidler2011).

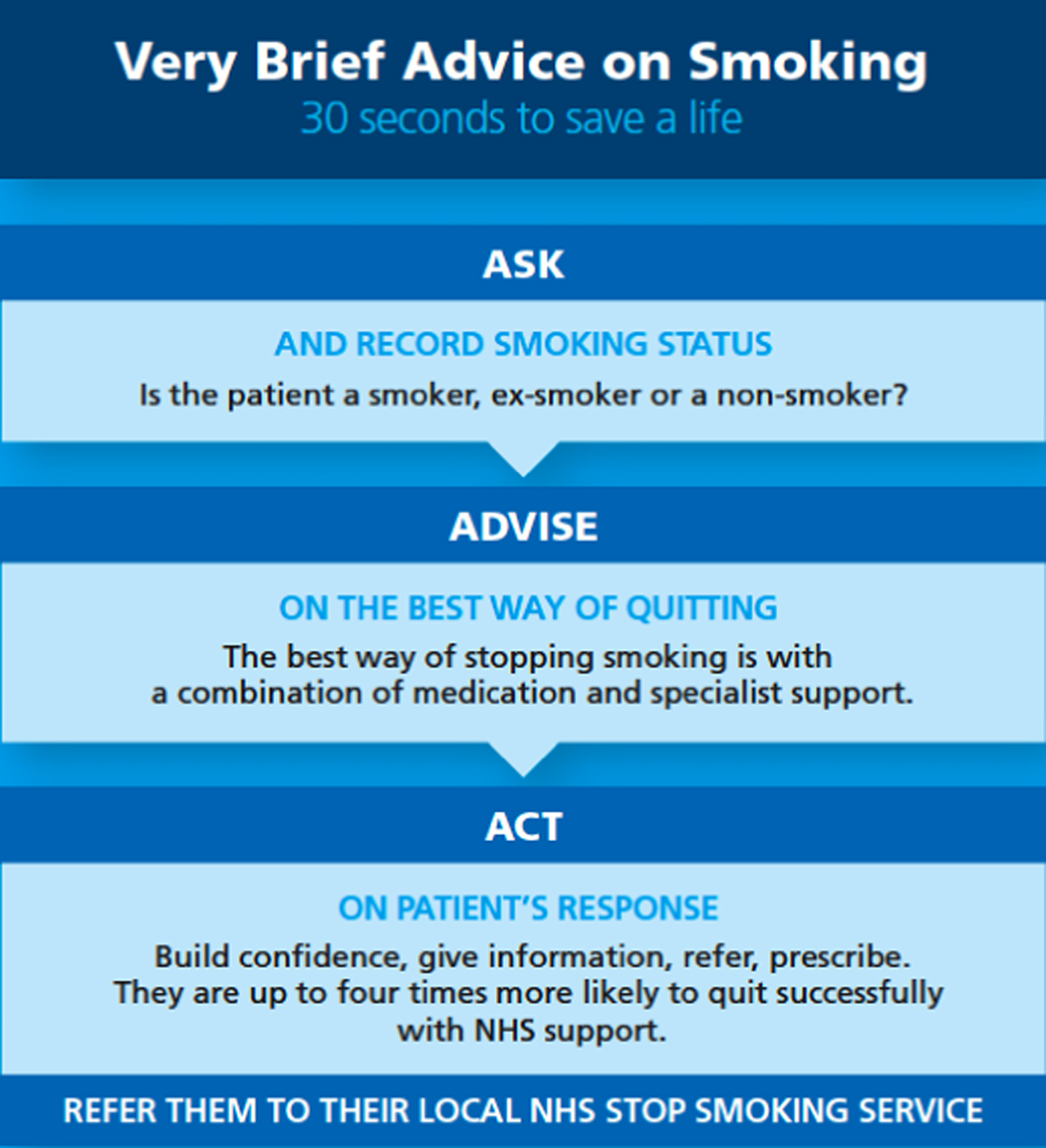

Very Brief Advice (VBA) on smoking is designed to be used opportunistically, in less than 30 s, in almost any situation with a smoker. The VBA model is based upon the PRIME theory of motivation (West, Reference West2006) and has been evaluated as effective in the UK (West & Fidler, Reference West and Fidler2011). Figure 1 shows the three elements of the VBA model: establishing and recording smoking status (ASK); advising on how to stop (ADVISE); and offering help (ACT). The VBA is designed to promote quit attempts, and in the UK, patients interested in quitting are then referred by their healthcare providers to the National Health Service (NHS) local Stop Smoking Service for support with quitting. VBA on smoking is a recommended clinical practice for all HCPs in the UK with more than 55,000 HCPs in the UK trained in VBA (NHS Future Forum, 2012; NICE 2013; NCSCT Statistics, 2018, unpublished).

Fig. 1. VBA on smoking intervention (standard UK model).

The acceptability and utility of the VBA model has not been examined in low-resource settings outside of the UK including LMICs. Given the resources to implement the VBA intervention may not be routinely available in these settings, examining methods for adapting the model to local circumstance is important (Murray & Jordans Reference Murray and Jordans2016). Local and cultural adaptation, are known to be critical for engaging local stakeholders and increasing the likelihood of an intervention's uptake into practice (González Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, Reference González Castro, Barrera and Holleran Steiker2010; Harrison, Legare, Graham, and Fervers, Reference Harrison, Legare, Graham and Fervers2010).

Aim

This report details experience in adapting the VBA intervention and training course content, originally developed in the UK, for use in three low-resources settings: Greece (Island of Crete), Vietnam and Kyrgyzstan undertaken as part of the FRESH AIR (Free Respiratory Evaluation and Smoke-exposure reduction by primary Health Care Integrated Groups) project (https://www.theipcrg.org/freshair) (Cragg, Williams, Chavannes, & on behalf of the FRESH AIR group, Reference Cragg, Williams and Chavannes2016).

Methods

Process of adaptation

Stakeholder engagement

In each country a lead was identified to support the execution of the Fresh Air project locally. Country leads were asked to engage with leading academics, clinicians and stakeholders to consider if, and how the VBA intervention and training programme would need to be adapted for use in their country.

Adaptation of VBA

UK VBA experts provided local experts with an orientation to the VBA intervention model, its principles, supporting evidence and approach to training HCPs. Using a participatory research process, UK experts and local stakeholders conducted an environmental scan and needs assessment to examine the VBA intervention model, training materials and recommended adaptations. Basis for reviewing and adapting VBA on smoking training (Table 1) was provided to the country teams to facilitate adaptation of VBA using a standardised approach. Suggested adaptations to VBA were then discussed with the UK team and agreement reached on how to implement the adaptations, and reflect them in the training courses, without diluting the principles of VBA. UK experts and local teams collaborated on the development of an adapted training course and materials (slides, train-the-trainer guide, participant guide) in the local language that reflected agreed upon changes. Two VBA training sessions were piloted in each country to further inform local adaptation. UK experts travelled to each country to deliver train-the-trainer support and observe the first training session. Following each training session, the need for further refinements was examined. A final set of training materials was developed based on these iterative feedback loops.

Table 1. Basis for reviewing and adapting VBA on smoking training

Results

Adaptation of VBA intervention model for use in low-resource settings

For the most part the VBA model remained intact. A range of local adaptations were made to the ASK, ADVISE and ACT elements of VBA in all three countries to ensure cultural appropriateness and sensitivity.

ASK – establishing smoking status

Doctors in each country felt that they had more time to talk with patients about smoking cessation than in the UK where GP consultation times last on average 9 min (Irving et al., Reference Irving, Neves, Dambha-Miller, Oishi, Tagashira, Verho and Holden2017). In response to this, a more discussion-based approach to addressing tobacco use with patients, which was more reflective of their respective communication styles, was recommended for the ASK element.

ADVISE – on the best way of quitting

Smoking cessation medications are limited in Vietnam, and whilst available in Greece and Kyrgyzstan are not covered by publically funded healthcare benefits and may be prohibitive as out of pocket costs for many residents. Despite these limitations doctors in all three countries were interested to learn more about pharmacotherapy, for those patients who could afford it.

ACT – on patient's response to advice

Smoking cessation support is also limited in parts of Greece and Vietnam, so the focus of the ACT element of VBA was on behavioural support, followed by medication and when available referral to specialised cessation support in these countries.

Adaptations to VBA training programme and materials

Adaptations to the VBA training reflected agreed upon changes to the VBA intervention model, but also what local stakeholders thought was important for trainees in terms of content, key messages and format of delivery. Adaptations across the three countries are summarised in Table 2, with several similarities documented across countries.

Table 2. Adaptations to VBA training intervention across three low-resource countries involved in the FRESH AIR project

In all three countries, there was a need to enhance key messages and expanding training content regarding nicotine dependence which was felt to be critical in engaging HCPs and increasing both motivation and empathy in their consultations with patients who smoke. In Vietnam, three key messages were added to the training to reinforce the chronic relapsing nature of smoking (Box 1). These key messages were also subsequently adopted by the team in Kyrgyzstan.

Box 1. Adaptation of key messages on the mechanism of tobacco dependence developed by Vietnam partners and used in Kyrgyzstan

Key messages:

1. People start smoking for various reasons, they continue to smoke because of dependence upon nicotine

2. Dependence is a disorder of motivation. People relapse not because they ‘want’ to go back to smoking, but because the suffer from repeated powerful motivations to smoke

3. How dependent people are does not matter in terms of VBA, the fact that they smoke or not is the key feature. Level of dependence affects the chances of success and thus the amount of support required

In Greece, adaptations also included ensuring factual details about health effects of smoking, data on prevalence and profile of local tobacco users and links between smoking and mental-health illness. Local HCPs reported that talking about smoking can be challenging in Greece (Crete), because locals often be a lack of concern for personal health and that a more conversational style of communication would be more accepted by patients. Therefore, a second method for how to ASK patients was included in the training that reflected the local communication style.

In Vietnam, the scarcity of behavioural support for smoking cessation, and the inability of many smokers to access stop smoking medications, led to additional content on evidence-based behavioural support techniques being added to the ACT element of the training.

In both Greece and Kyrgyzstan, there is no official national strategy to promote and support tobacco cessation or provide tobacco dependence treatment. Nevertheless, some cessation support is available, though GPs are not necessarily aware of it. To support the ACT element of VBA, the trainers included more detailed information about behavioural support, medications and when available referral information for local quit smoking services.

The art of implementing VBA in low-resource settings

Experience from the FreshAir project also highlighted that there are some key components of successful implementation, which go beyond adapting the physical teaching and learning resources. Successful implementation of the VBA on smoking intervention requires a shared vision, strong leadership, the identification of a core multidisciplinary team of enthusiastic trainers, who are credible by virtue of their clinical roles, and perhaps most importantly a team, which is fully engaged with the learning material. The important task of transporting novel evidence-based healthcare interventions from one diverse setting to another requires the delicate interplay between all of these elements.

Conclusions

Adaptation to the VBA training intervention is possible and small changes can be made to whom VBA is delivered by and too, and how the conversation with patients is framed, to ensure that HCPs are comfortable with the intervention. There were cross-country similarities documented including interest in expanding key messages and sections of the training. In countries where there is a lack of national or local supports for clinicians to refer to there is need to discuss alternative approaches for the ACT element of the model.

We are an implementation science project to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of chronic lung diseases where resources are limited. www.freshair.world.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the healthcare professionals who contributed to the process of adaptation. The authors also thank the FRESH AIR partners and the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) for their leadership in the execution of this work and the FRESH AIR Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC) http://www.theipcrg.org/display/FRESHAIR/Meet+the+Scientific+Advisory+Committee.

Financial support

The research leading to these results has received support from the EU Research and Innovation programme Horizon 2020 under grant agreement no. 680997 H2020 Health, Medical research and the challenge of ageing.

Conflict of interest

A. McEwen has received travel funding, honorariums and consultancy payments from the manufacturers of smoking cessation products (Pfizer Ltd., Novartis UK and GSK Consumer Healthcare Ltd.) and hospitality from North51 who provide online and database services. He also receives payment for providing training to smoking cessation specialists and receives royalties from books on smoking cessation. A. McEwen is an associate member of the New Nicotine Alliance (NNA), a charity that works to foster greater understanding of safer nicotine products and technologies. C. Lionis, S. Papadakis and I. Tsiligianni have received educational grants from Pfizer Global Inc. relevant to primary healthcare practitioners’ training in regards smoking cessation. I. Tsiligianni receives fees for participating in advisory boards and giving speeches to Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, and Novartis outside the submitted work. All other authors have no conflicts of interest related to this paper.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.