Introduction

In 2012, the late C. A. Bayly wrote that colonial histories up until then had primarily presented moments of registration as “instrumental intrusions, or even ‘epistemic violence’ on society perpetrated by colonial states intent on extracting revenue or classifying people.”Footnote 1 He urged historians to start looking past this Foucauldian lens and highlight the plurality of stakeholders involved in and utilising the registration processes that were part of imperial projects around the world. While the pluralistic and negotiable character of other domains and instruments of imperial and colonial states have been highlighted in recent literature, most prominently regarding legal pluralism, registration continues to be primarily understood as a tool for legibility and governmentality.Footnote 2 Looking at the case of eighteenth-century Dutch colonial Sri Lanka, I argue that registration as a colonial institution should similarly be reconsidered. Especially since registers were arguably even more deeply impacted through the actions of indigenous actors than legal institutions. Namely, because, first, those that were registered could negotiate what was registered during the process of registration, and this could later offer a form of recognition (most prominently in legal contexts). And second, and most importantly for this paper, while utilised as recognising documents, the registers could in turn be changed when the colonial authorities were confronted with new information—as I will demonstrate.

Both land tenure and registration are prevalent themes throughout Sri Lanka's history. In the precolonial societies, the importance of land ownership and tenure, and the inheritability of (caste-related) labour services, had led to an extensive documenting culture.Footnote 3 The early European colonial encounters with Sri Lanka's (coastal) society were characterised by the colonisers’ attempts to reap the benefits from the long-existing tenurial system, and document them—often using local scribes and records.Footnote 4 At the same time, this caused the respective colonial governments to having to deal with many conflicts and negotiations regarding land, labour and property with the local population. Subsequently, local communities, families and litigants became more and more experienced and skilled in navigating such institutions implemented by the colonial states, one of which being the colonial land and population registers (the thombos).Footnote 5

In this paper I will present several cases of the Dutch East India Company's (hereafter VOC, or Company) rural court (Landraad) of the Colombo province in Sri Lanka where indigenous litigants utilised the thombo registers to gain an advantage in civil court cases. I will show that these registers afforded the litigants recognition of their property and their personhood, while also highlighting that, in several cases, locally produced documents (such as the inscribed, dried palm leaves or olas) could actually be favoured by the colonial council over the colonial registers. Subsequently, this “local knowledge” could change the colonial registers at the council's request, setting up my central thesis that these registers were not just the product of a unidirectional knowledge production process, but affected by those recorded in it.

To test this hypothesis, I will be using a database encompassing thirty-three civil court cases that were held at the Colombo Landraad between 1767 and 1776.Footnote 6 As we shall see below, nearly all of the cases included at least one indigenous, or non-European, party. Most of them (19) revolved around conflict regarding land or other property. The others regarded a contested estate or inheritance (6), a loan or debt that had remained unfulfilled (3), a dispute about the registration of property (2), a disagreement following the transaction of a plot of land (1), the custody of a child (1), and a case surrounding alleged assault (1).Footnote 7 In the first segment of the paper I shall give a brief overview of the Landraad's institutional history within the context of legal pluralism that persisted in colonial Sri Lanka at the time.Footnote 8 This will offer some context for the subsequent two segments, in which I will, respectively, introduce the actors that were facing litigation in the Landraad's court room and the types of conflicts they were embroiled in, and the utilisation of colonial documentation (particularly the thombo registers) by said actors. Ultimately, I aim to highlight the utilisation of colonial records (both registers and deeds) by local litigants and—most importantly—reflect on how such records were appropriated and then, crucially, altered by local actors, and what that implies for our understanding of registration and law in a colonial context.Footnote 9

With regard to the overarching objective of this special issue, I will especially focus on how the utilisation of colonial documents as legal evidence could see such documents (and thus colonial knowledge) altered, and how local knowledge (e.g., through witness statements and locally produced documents) could impact colonial knowledge—highlighting the proposed “looping effect.”

The Colombo Landraad, a Brief Institutional History

Over the last few years, the judicial system that was present in Dutch colonial Asia has received a fair amount of attention in the literature.Footnote 10 In the wake of groundbreaking work on legal pluralism in empires initiated by scholars such as Lauren Benton, Tamar Herzog, and Paul Halliday, Nadeera Rupesinghe, Alicia Schrikker, and Dries Lyna, amongst others, have identified similar mechanisms where local customs shaped colonial lawmaking in the territories controlled by the VOC in Sri Lanka.Footnote 11 Specifically in regards to the Sinhalese customs and laws that were maintained in the southwestern lowlands of the island, which would remain uncodified until the nineteenth century, it has been shown that the different colonial courts created by the VOC at the time offered significant room for negotiation.Footnote 12 Similarly, the classification of people by different colonial institutions at the time was demonstratably dynamic, and local agents could—to some extent—influence the way they were recorded by the institutions belonging to the colonial state.Footnote 13

Despite this apparent fluidity, the Company's legal system in Sri Lanka was organised within a rigorous structure, at least on paper. The Council of Justice in Batavia (present-day Jakarta) was formally the highest judicial institution from where the VOC's laws were compiled and published, also for the specific domains governed by the Company in Asia.Footnote 14 In Sri Lanka the respective Councils of Justice of the three largest cities under VOC control, Colombo, Galle, and Jaffna, were considered the highest ranking courts—the first being the highest appellate court on the island. Ordered below these councils were two subordinate courts per district, the civil courts (civiele raden) and rural courts (landraden). These two courts handled all the civil cases amongst the population of, respectively, the urban and rural areas under Company control. The rural courts were specifically created to relieve the colonial official who had formally been solely responsible for all matters surrounding the local population and land tenure beyond the walls of the colonial cities.Footnote 15 For a multitude of factors too complex to list here, conflicts amongst local land owners (and their families) were frequent.Footnote 16 Thus, the sheer amount of cases involving land (either as a form of property or used as collateral in loans) necessitated the creation of the Landraden in the 1740s.

To accommodate this legal pressure, but also to facilitate the exploitation of agricultural surplus and caste-based labour, the Landraden would not only be responsible for handling the legal conflicts (principally about land), but also for the compilation of the thombo land and population registers. In an effort to increase their legibility of the hinterlands without relying on intel from local headmen, the Company had both indigenous and VOC officials record all plots of land in the territories surrounding the cities of Jaffna, Galle, and Colombo (and later also Batticaloa and Trincomalee in the east).Footnote 17 While the thombo was not a Dutch invention—rather it was introduced by the Portuguese colonisers a century earlier based on local land registers called lēkam miti—it was for the first time that the population and land of Sri Lanka's colonised coastal regions would be recorded on such a scale.Footnote 18

While the local communities that were actually being registered were hesitant at first, and regularly protested and sometimes even revolted during the registration process, over time they became increasingly aware of the recognition that these registers could offer to them. This recognition could prove vital in conflicts amongst themselves in, for example, the earlier-mentioned legal conflicts, but also vis-à-vis the colonial government.Footnote 19 This meant that the thombos were increasingly utilised as evidence by local litigants as well.Footnote 20 This dynamic makes the Landraad such a promising institution to study, specifically in relation to the objectives of this special issue. The colonial knowledge produced by the colonial state in the form of the thombo registers was not only partially caused by local interests, it was appropriated and directly utilised by local agents. Moreover, people actively tried to negotiate what was in the thombos, and the outcome of a court case could also change one's entry in the registers, as we shall see later on in this paper.Footnote 21 The fact that the Landraad was the colonial court practically exclusively used by indigenous litigants, in contrast to the other courts, makes it even more befitting.

Before moving on to the litigants and their legal conflicts, some final remarks are needed about the workings of the Landraad. The court was made up by several councilmembers of mixed ethnic and cultural backgrounds.Footnote 22 There were three permanent members, all of whom were white and direct servants of the VOC: the president (or the so-called disāva), the vice-president, and the secretary. Then there was an inconsistent number of commissioners who functioned as councillors who were of European, Eurasian, and Sri Lankan origin. Additionally there were clerks, translators, and procurators available to support the council, as well as a specific commissioner responsible for the upkeep of the thombo records (the “thombo keeper”). Just like the Landraad of Galle, the Colombo Landraad was situated a few (1.4) kilometres outside the colonial fort area in a village called Hulftsdorp. This was not a coincidence, nor a matter of convenience. Hulftsdorp literally functioned as an intermediary space between the fort area (which was only accessible for whites), and the hinterlands (where barely any Europeans would go). Thus, close enough to the centre of colonial power to maintain the security for the VOC officials working there, but far enough not to be a direct threat to the segregated VOC headquarters within the confines of the fortifications. In that sense the Landraad also literally functioned as the primary gateway for the people of the hinterlands seeking justice, as it was the first step towards the colonial judicial system past the local chiefs (whom functioned as arbiters for minor cases and conflicts in their respective regions).Footnote 23

Consuming the Law? Litigants and the Colonial Court, 1767–76

Of the thirty-three Landraad cases sampled for this study, all but three disputes were related to land. Either directly when there was disagreement over who was the rightful owner of a piece of land, or indirectly when, for example, the land had been used as collateral in a loan or was part of a larger conflict regarding the inheritance of an estate.Footnote 24 It is thus unsurprising that in 61 percent of these cases either one or both party/parties requested an extract to be made of one of the thombo registers to put forward as evidence to their case(s). Before we can make more significant statements about the impact of such colonial registers as legal documents, we should look more closely at who these litigants were. In short, who looked for justice in the colonial courtroom of the Landraad? What was the gendered and socioeconomic make-up of the litigants? And what was the geographical reach of the court (i.e., what distance would litigants travel to have their cases heard by a colonial council)? Answering these questions will help us determine not only exactly which actors from which social group had access to the colonial knowledge and institutions, but also which ones could negotiate, appropriate, and potentially have an impact on both (and thus facilitate the looping effect).

Similar to what was found for Galle by Rupesinghe, the Colombo Landraad was a relatively accessible court.Footnote 25 For example, while most litigants, particularly the plaintiffs, were men, and some of them came from the slightly higher echelons of society, it could afford access to justice for more marginalised groups in society. When it comes to gender, twenty-four of the thirty-three primary plaintiffs—which in case of a party consisting of multiple plaintiffs was the one recorded as the principal one representing the others—were men, as opposed to the seven female plaintiffs. It is telling that the number of female plaintiffs rises to thirteen if you count all the plaintiffs within multi-litigant parties, however, in at least two such cases it were not male representatives that were recorded as the primary plaintiffs, but other women who ganged together to sue an opposing party instead.Footnote 26 Furthermore, women seem to have had as much a right to request extracts to be made of their entry in the thombos as did men.Footnote 27 In such situations, using the colonial legal structures and knowledge produced by them (for example, that which was recorded in the registers) could aid in protecting their property from family members who would potentially have had the power to forcefully occupy a family's estate otherwise.Footnote 28

Similarly, in some cases people from lower classes of society could use the court to challenge their higher-classed rivals. For example, in one case two brothers challenged before the court a high-ranking chief (a mudaliyār) who had allegedly occupied their father's land and subsequently had it recorded in the thombos as his own.Footnote 29 The brothers argued that their father had rightfully owned the land as compensation for the fact that he had helped clear the land, dug the canals, and finally aided in the cultivation of the land for the mudaliyār. As the only heirs of their father, the land should now be theirs. The mudaliyār initially disagreed, stating the brothers lost their claim when they left their village (and father) behind. However, under pressure from the pending legal conflict, the mudaliyār and the brothers managed to settle and make a new division of the land with some of the Landraad's indigenous commissioners as mediators. Considering the very powerful position of the mudaliyār and the clear dichotomy in social status (as the father of the plaintiffs had been a labourer in service of the chief), choosing to have this conflict judged by the colonial court rather than facing the mudaliyār on his home turf clearly afforded the brothers to force the regional headman into a settlement.Footnote 30

Further emphasising the accessibility of the Landraad is the cultural and socioeconomic diversity of the individuals that opted for this colonial court to settle their legal conflicts. Going by the social categories applied to the litigants by the clerks of the Landraad (see table 1), we can see that a wide array of people from many different sociocultural standings utilised the council.Footnote 31 What stands out is that besides a few Eurasian/European individuals, almost all (close to 90 percent) litigants hailed from local, or Asian, communities.Footnote 32 While caste was often the central category in the thombos, the Landraad seemed to have maintained either more proto-ethnic identifiers (like “Sinhalese,” “Moors,” and “Chetties”), or they used one's service title or occupation (like the lascarins, the saparamādus, and the different kinds of headmen).Footnote 33 This choice was based on the fact that both one's communal background and one's title and subsequent duties had legal consequences.Footnote 34 For example, local customs and laws differed significantly between the Sinhalese on the one hand and the Moors (maintaining a form of Islamic law) on the other.

Table 1. Number of litigants based on social categorisation as applied by the Landraad, categories standardised by author*

Source: database of SLNA 1/4784, 4785, 4787 & 4789

* Meaning I have discerned the litigants’ social classifications based on a combination of their names, social categories given by clerks, self-identification by actors, and caste. Note that I have accumulated those that were recorded by their caste under the (proto-)ethnic category that was also used at the time (e.g. the members of the āchāri caste as Sinhalese). For a more broken down report of the actors’ classifications: see Bulten, ‘Reconsidering Colonial Registration’, 252.

Basically each of these communities had their own arbiters yet chose the Landraad's jurisdiction instead for a variety of reasons. Often, it was clear intracommunal conflicts, most prominently within families, that either could not be solved by the local authorities (or they had failed to do so), or of which either party felt the outcome of the conflict could be significantly swayed in their favour if they opted for the colonial court.Footnote 35 However, several conflicts were also of an intercommunal nature and thus were perhaps born out of necessity, because the litigants involved were either not willing or able to have the conflict solved by either communities’ arbiters. We should be wary, however, to jump to such conclusions, as in many such intercommunal cases it becomes very apparent that the litigants in question were in fact very much members of the same social world. Additionally, in many cases where witnesses were called before the court to testify, these witnesses came from diverse social backgrounds and also clearly had direct relationships with the litigant parties in question.Footnote 36

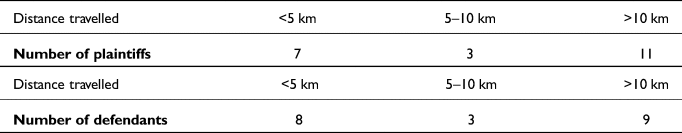

A final indicator to determine which actors had explicit access to the Landraad, the colonial knowledge produced there, and thus the possible ability to alter that knowledge, was the litigants’ physical distance to the court. As was observed for Galle, the majority of the litigants of the Colombo Landraad lived in close vicinity to the court.Footnote 37 However, there were several cases where plaintiffs, defendants, and/or witnesses came from much further distances, sometimes repeatedly so. Specifically, the average litigant travelled thirteen kilometres (see tables 2 and 3).Footnote 38 Travelling on foot via muddy footpaths through the forested hills of southwestern Sri Lanka, this probably took half a day to a day. This was the case for about fifteen out of the forty-one litigants for whom we could reconstruct their residence at the time.Footnote 39 For them, it is probable the Landraad was their first choice to have their cases heard, especially if it considered conflicts surrounding land or debts below a value of eighty rijksdaalders.Footnote 40 Yet, some litigants were observed traveling up to even fifty-eight kilometres—sometimes doing so several times as the trial progressed. Witnesses for such cases would travel similar distances as well.Footnote 41

Tables 2 & 3. Distance of plaintiffs and defendants respectively, categorised

Source: database of SLNA 1/4784, 4785, 4787 & 4789

All in all, while the Landraad's most direct sphere of influence may have been within the more “traditional” range of an early modern colonial institution (the port city and the lands directly surrounding it), the social reach of the Landraad should not be underestimated. In the words of Rupesinghe: “By the mid-eighteenth-century, the indigenous inhabitants were acquainted with the Landraad and its thombo registration, and were able to use that knowledge in settling disputes.”Footnote 42 As observed for both Galle and Colombo, this acquaintance went well beyond the borders of the colonial cities. Additionally, as we have seen, the Landraad also offered a space for more marginalised groups in society in their struggle for justice, particularly women and lower-class individuals. In it, the thombos could offer recognition and protection of property, and they were regularly brought forward as evidence by local litigants, as we shall see below. Thus, it seems the Landraad and their land registers allowed many different agents to access, utilise, and potentially alter colonial knowledge.Footnote 43

However, as was stated by Rupesinghe, the Landraad's apparent “inclusiveness” should not be overappreciated.Footnote 44 She argued that access to indigenous legal systems would have been available for both women and low-ranking individuals of society as well. Similarly, the registration and recognition of property and personhood was not a novel, colonial invention either. Locally produced documents—particularly the earlier mentioned olas, inscribed by highly specialised clerks and scribes—seem to have been deeply manifested into local society.Footnote 45 In a way it was rather the local knowledge that would be included into the colonial knowledge, rather than the other way around. Where indeed colonially produced knowledge (i.e., the thombos) was utilised by local litigants, it was almost always supplemented with locally produced evidence in the form of the earlier-mentioned olas, but also through witness statements and other modes of information transfer that were incredibly valuable to local society.Footnote 46 These supplements had an impact on colonial knowledge and did alter what was known by the colonial state bureaucracy, as we shall see below.

Registration and Recognition? Utilising and Altering Colonial Knowledge

As was mentioned before, in twenty of the thirty-three studied Landraad cases, at least one of either legal parties requested a thombo extract to be taken for them, or brought an existing extract of their entry in the register with them to court.Footnote 47 Additionally, litigants brought records of previous court cases, deeds signed by colonial officials, last will and testaments compiled by colonial offices, and many other products of the colonial knowledge-making process in a bid to compile sufficient evidence to support their respective cases. It is apparent that local litigants understood the importance of evidence within the Dutch-Roman legal framework, and were aware of the fact that producing a colonial document as evidence could aid them in furthering their case.

The utilisation of such records as legal evidence by local actors was not inconsequential for the colonial state. The outcome of civil cases could alter what was known by the state. To be more precise, in at least five of the thirty-three studied cases, the entry of a land or family in the thombo had to be changed based on the outcome of the court case in question.Footnote 48 Additionally, as we shall see below, such changes to colonial documents could be determined by locally produced evidence—such as witness statements and, more importantly, the aforementioned ola documents. In this final segment of the paper I want to explore this dynamic between colonial knowledge production and local knowledge, specifically within the confines of the colonial courtroom. I will also reflect on the impact it had on both local litigants and on colonial record keeping, and on the notion whether we should thus call this process “colonial” knowledge production at all.

To come up with a meaningful comparison of the types of evidence employed by the local litigants that utilised the Landraad's judicial apparatus, we first have to determine what we understand as evidence, and what we do not. In this case, evidence is defined as documents—either paper or palm leaves—typically compiled for a purpose not related to the court case itself, containing information that provides proof or information in favour of the litigant presenting it to the court. I have only accepted self-gathered evidence, meaning documents acquired by litigants outside of the courtroom to be brought into the courtroom and presented there to support their claims. So no (witness) statements before or at the request of the Landraad, or (request) letters or olas sent to the council,Footnote 49 nor thombo extracts requested by the councilmembers rather than either legal party.

For the sake of argument, I have divided the types of evidence encountered in the court cases into two broad categories: locally produced evidence and colonially produced evidence—even though I would argue such binary understandings of these documents would intellectually be quite unproductive given the entanglements between the two.Footnote 50 That said, roughly all “locally produced evidence” stems from documents and knowledge that were (largely) created outside of the colonial knowledge-making infrastructures. Typically, such local knowledge and information was inscribed on olas. Specific examples are wills/testaments (e.g., “testament ola”), written statements of witnesses (often via olas), or other types of olas recording transactions, pawning, or inheritance matters.Footnote 51

Conversely, colonially produced evidence is evidence stemming from records created by the formal colonial bureaucratic apparatus. Usually, such records were made on paper, were created with a certain political purpose in mind, and had only become the property of local litigants because the documents in question were granted to them (e.g., as a copy, as proof, or as a receipt), or because the litigant in question requested an extract to be taken of the original record (e.g., the thombos).Footnote 52

While there were some cases where either or both parties failed to present evidence to the council, the majority of the legal parties engaged in civil conflicts before the Landraad did manage to bring forward documents to prove their claims.Footnote 53 As was mentioned before, practically all of these parties were local or Eurasian agents. Despite that, both the plaintiff and defendant parties in the cases studied had a slight preference for presenting colonially produced evidence to the Landraad (see tables 4 and 5). The most common amongst the colonially produced types of evidence were, unsurprisingly, the thombos (see table 6). They were followed by several types of transcripts or receipts received from previous court cases within the Dutch colonial legal system, as well as some land deeds. In the context of the Landraad, it makes sense such documents were frequently cited by litigants. Almost all conflicts regarded land, which the colonial state formally claimed full sovereignty over. Thus it made sense to use the documents created by this state to have your property recognised through the state's own bureaucracy.

Tables 4 & 5. Source of types of evidence used by plaintiffs and defendants respectively

Source: database of SLNA 1/4784, 4785, 4787 & 4789

Table 6. Different types of colonially produced evidence presented by litigants of the Landraad

Source: database of SLNA 1/4784, 4785, 4787 & 4789

To illustrate how the utilisation of colonial documents like the thombos by local litigants worked in practice, let us zoom in on a specific case. On 17 July 1767, a man named Koenje Tambie Sekadie Markair—self-identifying as a Moor headman and inhabitant of Aluthgama—signed a document in which he confirmed that the three different documents he had presented as evidence to the Landraad had been returned to his possession after the Landraad's secretary had taken copies of them.Footnote 54 One of the documents given back to him was an extract of the land thombo of the Kalutara district (see figure 1). Koenje had used this extract to prove to the council members of the Landraad that he had owned three plots of land in the vicinity of the village of Malewane. While it was not specified how Koenje had come into possession of this extract of the colonial register, normal procedure would have it that he had visited the office of the thombo keeper, paid a twenty-four stuiver fee, and received a copy of his entry in the register from one of the thombo keeper's clerks. It seems Koenje had owned this extract before ever needing it in a court case—suggesting people like him kept records of their possessions as a precaution, not just as a reaction to a legal conflict.Footnote 55

Figure 1. Map displaying the kōralē subdistricts of the Colombo disāvany (district), political situation post-1766, (portrait).

It would turn out that Koenje's prudence was not unwarranted, because sometime before 17 July 1767, three local farmers had written a letter to the first officer of the Landraad complaining that the plots Koenje owned were actually theirs.Footnote 56 All three farmers claimed that their families had cultivated the plots of land near Malewane for years, before Koenje had supposedly struck a deal with several local members of the goygama caste (landowners and agriculturists) to take them over. Koenje, in contrast, was able to show the Landraad an ola stating that he had legitimately acquired one plot of land through a purchase, and claimed he had owned the other two plots for as long as he could remember.Footnote 57 All three of the plots were also recorded in the thombo as his. Crucially, Koenje had witnesses come to the Landraad to testify that when the thombo registration process was ongoing several years ago, the claimants had been present, yet had not objected to Koenje having the plots of land registered as his.Footnote 58

The Landraad would end up believing Koenje's defence, and confirmed his property over the contested plots of land. Koenje's record keeping had clearly helped him in having his property recognised in, and protected by, a colonial court—and thus by extension the colonial state. Additionally, this case highlights the importance of the thombo registration process for local land owners, and that it mattered whether one was present during this process to ensure one's lands were properly recorded. A final element worth mentioning is a claim made by the plaintiffs after the Landraad had already decided Koenje was in his right to own and cultivate these lands.Footnote 59 They said that one of the lands was smaller than what was recorded in the thombo. While this did not change the verdict, the Landraad did—crucially—order to have the excessive land recorded separately, and have it split between Koenje and the three plaintiffs. I say crucially because it offers us a glimpse as to how local actions could change what was recorded in the thombos (and thus what was known by the colonial state).

In the end, the alteration to the thombo made after Koenje's case was marginal, but other cases show us that other legal conflicts could lead to more significant changes in the colonial registers. At least six of the thirty-three cases regarded an allegedly faulty thombo entry, or at least one that was countered by either litigant.Footnote 60 In almost all of those situations, either one or both legal parties presented alternative evidence to counter the information recorded in the register. To give an example, in July 1767 one Barendigampollege Siman Perera from Mulleriyawa presented to the Landraad both a transaction ola and an ola compiling several written testimonies supporting the claim that his parents’ land had been divided amongst him and his seven siblings many years ago.Footnote 61 He did so to challenge his sister, Catharina, who had claimed the land was all hers and was recognised as such in the thombo.

The conflict was caused by a share of his parents’ debt that Siman had inherited along with his share of the land. To pay his debt, he had taken a loan from his sister, using the land as collateral. Yet, when after three months Siman returned to his sister to pay her back and reclaim his land, she had allegedly refused to return the land to him. Moreover, it seems that in the meantime she had secured the land as her property in the colonial registers.Footnote 62 Indeed, the thombo entry presented to the Landraad confirmed the land “was gifted by […] Adriaan Perera [the father] to his daughter Catharina Perera for reasons unknown, and is in her possession since.”Footnote 63

Probably thinking this would sufficiently persuade the Landraad into confirming her status as landowner, Catharina did not mount any further legal defence. However, Siman, as briefly alluded at before, brought the written testimonies (on olas) of several witnesses from the village to testify for him. These individuals, many of them village elders, vouched for Siman and said that it was known that the children of Adriaan Perera all equally shared their late parents’ land. Subsequently, the Landraad decided it sufficiently proven that Siman and his other siblings legally had a right to a share of the land that was registered as fully owned by Catharina in the thombo at the time. Catharina was to withdraw her claim and give access to the plot to Siman and their other siblings.

However, the Landraad did more than that. They also ordered the thombo keeper to alter the register. It was to be known without a doubt that the eight siblings each owned an equal share,Footnote 64 which apparently happened without any further objection from Catharina. So while the colonial records had represented a reality beneficial to Catharina, her brother was able to challenge this representation—using the knowledge of witnesses and local documentation—and in the end change the paper reality as it was known in the colonial registers at the time.

While in themselves cases like the ones described above do not seem very radical, the frequency with which such cases led to alterations in the colonial records is noteworthy.Footnote 65 The fact that local litigants utilised colonial knowledge to gain the upper hand in civil conflicts is interesting in itself. However, the way in which local testimonies and ola records could consistently impact the colonial body of knowledge is even more fundamental—and subsequently suggests colonial archives are made up of more than just the epistemology (and anxieties) of the colonisers alone, as was famously suggested by Stoler.Footnote 66

Rather, our current understanding of legal pluralism in colonial societies should be enriched with the notion that colonial knowledge was largely produced through (re)negotiations with local agents presenting local knowledge (and material) to colonial institutions like the Colombo Landraad.Footnote 67 This is important because colonial knowledge—like in the thombo registers—was primarily created by the colonial state for the purpose of extracting resources and revenue.Footnote 68 Yet, it was at the same time appropriated, influenced, and changed by local agents following their own ambitions.Footnote 69 Like how the “categories” of mental illness made up by medical experts and institutions were subsequently changed by the behaviours of the categorised—as described by Hacking, and introduced earlier in this special issue—the land registers recorded by the Landraad were constantly adapted at the request of local litigants.Footnote 70

That indigenous intermediaries, like clerks and translators, helped with the creation of colonial knowledge is by now a well-known phenomenon.Footnote 71 But the fact that this knowledge was used and subsequently altered through the actions of (in this case) local litigants is an area of study that is far less explored. Additionally, rather than through major acts of resistance, colonial knowledge could be changed through much more mundane acts, like protecting one's legal rights or seeking recognition for one's legal property. And as populations governed by (foreign) empires became more and more skilled in the “art of being governed” over time, such acts would have increased in scale and variety, upholding the aforementioned looping effect.Footnote 72

Specifically for the Sri Lankan case, a colonial register that was aimed at supporting the exploitation of agricultural produce and labour was turned into an instrument recognising property—an instrument that could be altered by those registered, if need be. More broadly speaking, this case exemplifies how we should reconsider the process through which colonial knowledge was produced by looking at the way colonial registers and other such documentation could be utilised and renegotiated by those that were documented by the bureaucracies of empires. Perhaps even more importantly, this idea forces us to reflect whether such knowledge production processes were actually exclusively colonial at all—and thus, whether we should be calling them colonial.

Concluding Remarks

To summarise and conclude, I have shown how an eighteenth-century colonial courtroom in Colombo, Sri Lanka, not only afforded local litigants to utilise colonial knowledge to defend their property but offered them a chance to change said knowledge. I have done so by presenting the case of the Landraad, or rural council, of Colombo, which was established by the VOC in the eighteenth century. Specifically, I have studied thirty-three civil court cases, primarily between Lankan and/or Eurasian actors, that were taken on by the Landraad between 1767 and 1776. In doing so, I have first established that the Landraad served as an intermediary judicial space between the colonial state and the inhabitants of the hinterlands under VOC control in southwestern Sri Lanka. At the same time I have highlighted how this institution was responsible for the registration of people and property to facilitate the exploitation of labour and taxable produce. However, these registers could also be used by local litigants to have their property or estate recognised. Importantly, the question was who could do so, and to what effect.

To answer these questions, I have, second, argued that the Landraad was accessible to people from differing echelons of society. While most litigants embroiled in civil conflicts before the Landraad were male, and of relatively high socioeconomic status, the court also offered women and more subalternised groups of people a chance to litigate—and to potentially impact the way their property was registered. Third, I have highlighted that local actors frequently used documents produced by the colonial bureaucracy—specifically the thombo land and population registers—as evidence to support their cases. Fourth, and most importantly, I have shown that in doing so, these actors sometimes succeeded in permanently changing their entries in the very same colonial documents they utilised. This happened, for example, when contrasting information was presented to the colonial court in the form of written documents, e.g., on olas, or through witness statements.

Like how Ian Hacking proposed that the actions of the “categorised” could impact the categories with which they were categorised, I argue that this renegotiation of colonial documentation caused a similar looping effect. In this loop, the colonial state registered colonised people and their property, whereupon the registered utilised said documents in legal conflicts which in turn could change the knowledge itself when introducing new knowledge.

All in all, I argue that by using the principle of colonial knowledge looping between the colonial bureaucracy one the one hand and the behaviours of local agents on the other, we can (and should) reconsider the process through which colonial knowledge was produced. Not only was the colonial knowledge production process influenced by indigenous intermediaries—like clerks, guides, and translators—but it could also be renegotiated by individual agents after the initial moment of documentation. While such individual cases seem insignificant at first sight, on a greater scale this means that colonial knowledge could both be appropriated and altered by local agents. In other words, colonial epistemologies should not be understood as mere foreign perceptions of indigenous societies, but as the products of processes of negotiation and renegotiation between those documenting and those documented—and as such should perhaps not be understood as exclusively colonial at all.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank both the anonymous reviewers and the editorial board (and specifically the copy editor and editorial assistant of the journal) for their meticulous efforts to improve both this piece and the issue in general. Additionally, a word of thanks to all the participants of the “Looping Back Bureaucracies?” workshop held online back in 2021, which marked the beginning of a fruitful collaboration, the result of which lies before the reader. Special thanks also to Fabian Drixler (Yale University) for sharing his geographical data for the map, and Thijs Hermsen (Radboud University) for designing said map.

Funding Statement

The research underlying this article was made possible through the NWO-funded project Colonialism Inside Out: Everyday Experience and Plural Practice in Dutch Institutions in Sri Lanka, 1700–1800 (360-52-230), which was carried out in cooperation between Leiden University and Radboud University Nijmegen.