Unku: Insignia of Inka Power

Inka unku are garments with great symbolic meaning, directly linked to the upper echelons of the Inka Empire from the fifteenth to the sixteenth century (Cummins Reference Cummins, Burger, Morris and Mendieta2007; Pillsbury Reference Pillsbury2002; see Figure 1). The Sapa Inka not only wore unku, woven from the finest camelid (vicuña) fibers, but also gifted unku to officials, leaders of conquered territories, and military commanders (Murra Reference Murra1975; Rowe Reference Rowe1978, Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979, Reference Rowe1992)—thereby perpetuating a strategy of asymmetric reciprocity, with recipients expected to compensate the state for its generosity while reinforcing state control by lending legitimacy and power to government agents (Murra Reference Murra1975; Santoro and Uribe Reference Santoro, Uribe, Alconini and Covey2018; Santoro et al. Reference Santoro, Williams, Valenzuela, Romero, Standen, Malpass and Alconini2010; Zori and Urbina Reference Zori and Urbina2014).

Figure 1. Examples of unku discussed in this article: (a) toqapu unku, © Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, DC (PC.B518.PT); (b) black-and-white checkerboard unku, Field Museum of Natural History (1534); (c) Inka key unku, courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History (41.2/964); (d) diamond waistband unku, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Alfred C. Glassell Jr. (2001.1399); (e) toqapu waistband unku, University Museum, University of Pennsylvania (27569); and (f) zigzag waistband unku, Brooklyn Museum (41.1275.106). (Color online)

The symbolism of Inka corporate art is deeply rooted in Central Andean cultural history (Berenguer Reference Berenguer, Albeck, Ruiz and Cremonte2013). In the absence of a formal writing system, Inka material culture communicated important cultural information (Bray Reference Bray2000). Given the relationship between unku and Inka power, the presence of a previously unknown unku in a prehispanic archaeological context on the far north coast of Chile suggests that this so-called marginal territory received more imperial attention than previously thought (Figure 2). In this article we compare the diagnostic stylistic and technical attributes of the Caleta Vitor (CV) unku with such attributes from previously documented and historically depicted unku.

Figure 2. The CV unku: (a) folded in half; (b) laid flat, neck slot at center (photo courtesy of Paola Salgado). (Color online)

Archaeological Context

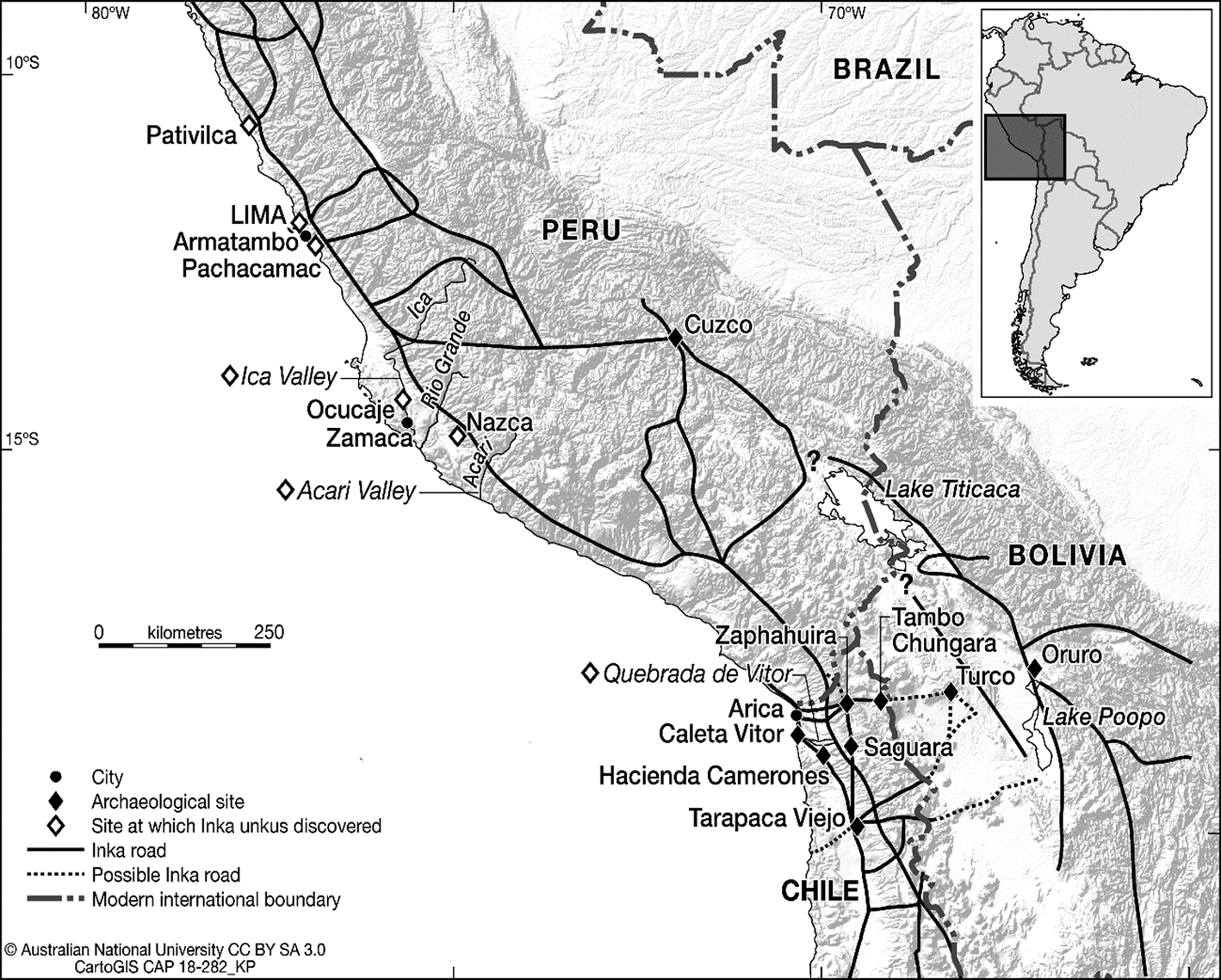

The Caleta Vitor archaeological complex is located at the Pacific coastal end of Quebrada de Vitor, a narrow, steep-sided canyon in northern Chile's Atacama Desert (Figures 3 and 4). The complex comprised seven zones (CV1–CV7) representing more than 9,000 years of occupation (Carter Reference Carter2016). The CV unku was recovered from a looted burial containing disarticulated human remains of at least two individuals, some of which had been previously removed from the chamber. Other artifacts cached in the chamber were two coiled hats, a miniature bow and five arrows, five bags, and numerous fragments of twined mats and textiles (Carter Reference Carter2016:Figure 7.13). Because of the disturbed nature of the burial, it is not clear which individual was associated with the unku.

Figure 3. Map of proposed Inka roads, archaeological sites, modern cities, and Inka unku sites.

Figure 4. Archaeological zones, Caleta Vitor. (Color online)

Results of Technical and Stylistic Analysis

Although Inka textiles are recognized for their standardization in style and construction, Anne Rowe (Reference Rowe1978, Reference Rowe1997) considers technical features such as dimensions and construction methods to be a more reliable method of identification—style being easier to replicate (for technical descriptions of weaving techniques, see Emery [Reference Emery1980]). To establish whether the CV unku is actually an Inka unku, we compiled the largest known database of prehispanic Inka unku, comprising 36 full-size garments (Supplemental Table 1); this database contains more than twice as many unku than recorded in John Rowe's (Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979) landmark study. The dimensions of all but three of the unku investigated in the study were recorded, with only one limited to a width measurement. Unsurprisingly, the results from the large sample showed greater variability than previously reported.

Earlier studies (Pillsbury Reference Pillsbury2002; Rowe Reference Rowe1978, Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979, Reference Rowe1992) found unku width to be more standardized than length, and this was confirmed in our analysis (Supplemental Table 2). Our assemblage contained widths (70–98 cm) outside John Rowe's range (72–79 cm) but averaging 76.2 cm (σ = 4.60), within the expected range. Length measurements ranged from 79 to 110 cm, with an average length of 89 cm (σ = 5.04), slightly below Anne Rowe's average (Reference Rowe1978:7).

We recorded one large outlier (98 × 110 cm; RT2377, Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú). Its dimensions did not significantly alter the standard deviations of width or length in the sample but did significantly affect the standard deviation for black-and-white checkerboard (BW) unku, because of the smaller number of those garments. For this reason, it was eliminated from our calculations. With the exception of this very large BW unku, the width range was 73.5–80.0 cm, a maximum of 1 cm outside John Rowe's (Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979:247) range, thus confirming consistency in BW unku size. We also noted a similar degree of standardization in diamond waistband (DW) unku (Supplemental Table 1). During analysis, we found that a t'oqapu waistband (TW1) unku had been rerecorded at 80 × 71 cm, now the typical measurement for an unku. The CV unku (91.0 × 80.5 cm) is slightly wider than average (76.20 cm) but within the established range.

The CV unku was woven using an interlocking tapestry technique consisting of two warps joined by 3/3 dovetailing along the shoulders (Figure 5a). The warp consists of two-ply and three-ply cotton yarns (Z-spun/S-plied), whereas the wefts consist of camelid fiber (Z-spun/S-plied), with eccentric wefts along the edge of the yoke providing a smooth edge (Figure 5b). Diagonal lines (defined by Emery [Reference Emery1980:233] as lazy lines) in the tapestry weave within blocks of single colors occur in the large, reddish area (Figure 5c). The fabric is double faced with no loose weft ends and a moderately high thread count (40 wefts: 7 warps per cm) with overcast edges. Although insufficient edge seams remain, the garment was presumably sewn up to the armholes. The neck slot is woven using discontinuous warps (Figure 5d).

Figure 5. CV unku features: (a) 3/3 dovetail shoulder join; (b) eccentric wefts creating a smooth edge along the yoke; (c) lazy line in the solid red area; and (d) neck slot with discontinuous warps. (Color online)

Although most unku are woven using a single warp, John Rowe (Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979) identified three examples woven in two warps like the CV unku (Figure 5; Supplemental Table 1). An unku in the Chicago Field Museum (catalog 1534) described as “in two pieces” may also have been joined in this way.

Dye analysis is still underway using high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Preliminary results, however, indicate that the black, yellowish, and white fibers were undyed, but the red color between the yoke and checkerboard area came from carminic acid and purpurin (Jian Liu, personal communication 2015). Carminic acid is produced from Dactylopius coccus (cochineal insect), a parasitic scale insect that lives on prickly pears (Opuntia cacti). Native to subtropical South America, Mexico, and Arizona, it has been used as a dyestuff in the Arica region from at least 1000 BP and earlier in Peru (Cassman et al. Reference Cassman, Odegaard and Arriaza2008). Vegetal dyestuffs containing purpurin obtained from Relbunium spp. and Galium tinctorum are native to the Andes and were in common use by the Late period (Niemeyer and Agüero Reference Niemeyer and Agüero2015).

Discussion

Four Inka unku styles were identified by Anne Rowe (Reference Rowe1978) and John Rowe (Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979). Pillsbury (Reference Pillsbury2002:71, 73) focused on the spatial arrangement of the Inka designs, describing them as boldly geometric, favoring plain color blocks with “certain areas of elaboration” on the waist, neck, and lower border, which possibly represented information about the wearer. Anne Rowe (Reference Rowe1997) identified three consistent features in the spatial organization: (1) the stepped yoke, exemplified by BW unku; (2) a pattern change halfway down the garment, exemplified by Inka key (IK) unku; and (3) decorative waist bands, exemplified by diamond waistband unku.

The CV unku features three of these diagnostic elements: a vertically striped yoke, surrounded by a reddish area, and a black-and-white checkerboard pattern across the bottom panel (Figure 2). This arrangement does not strictly conform to the established style (Rowe Reference Rowe1997; Pillsbury Reference Pillsbury2002), but construction techniques, dimensions, and spatial arrangement follow classic Inka conventions.

The most common unku style is the BW unku (Figure 1b) featuring a red, stepped yoke with black-and-white checks; it is associated with military officers in Francisco de Xerez's 1891 account of Atahualpa's army (Pogo Reference Pogo1936) and Guaman Poma de Ayala's drawings (Guaman Poma de Ayala et al. Reference Guaman Poma de Ayala, Murra, Adorno and Urioste1980 [1615]:Figures 38, 54, 98).

The black-and-white checkered area across the bottom panel of the CV unku is in precisely the same position as the horizontal stripes on IK unku and zigzag waistbands (Figure 1c; see Rowe Reference Rowe1978:Figure 32) and on DW unku (Figure 1d) described as the “lower panel” (Rowe Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979:250). The checkerboard on the CV unku is executed in four rows of squares, 11 on one side and 10 on the other (including partial edge squares; Figure 2b). The squares (8.0–9.5 cm × 7.3–9.5 cm) are comparable in size to the average size (7.4–7.9 cm; Rowe Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979:247), not including the partial checks at the edge of the garment (4.0–4.2 cm wide).

Technically, the CV unku compares favorably with the 12 diagnostic attributes in Supplemental Table 3. To our knowledge, the CV unku is the only extant example of this particular arrangement, but firm correlates appear in historical documents, including a sixteenth-century coat of arms depicting Topa Inka Yupanqui, who expanded the Inka Empire into northern Chile in the early 1400s (Figure 6a; Cummins Reference Cummins, Burger, Morris and Mendieta2007:Figure 24). This Hispanic colonial depiction shows an unku with a straight-sided yoke, elaborated with small diamonds, over a solid color with a border of black-and-white checks, and a zigzag line and row of smaller checks across the bottom. The spatial arrangement is unusual in that the area between the yoke and the checkerboard is larger than that on IK or DW unku.

Figure 6. Historic depictions of unku with features comparable to the CV unku: (a) coat of arms depicting Topa Inka Yupanqui, eighteenth century (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Rare Book Collection); (b) soldier at a Coya Raymi Quilla celebration (Guaman Poma de Ayala et al. Reference Guaman Poma de Ayala, Murra, Adorno and Urioste1980 [1615]:98). (Color online)

Another correlate appears in a drawing (Figure 6b) of the Coya Raymi Quilla celebration (Guaman Poma de Ayala et al. Reference Guaman Poma de Ayala, Murra, Adorno and Urioste1980 [1615]:98). The only observable differences between this and the CV unku is its striped yoke, which is unlike conventional “stepped” types on BW unku (Supplemental Table 1). The “stepped” effect is created by “setting back the top of each vertical row [of squares]” (Rowe Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979:247). The CV unku's checkerboard pattern does not border the yoke and has no stepped pattern.

The stripes on the CV unku yoke are idiosyncratic: they are narrow (0.7–0.9 mm wide) and arranged in a repeated pattern of black, yellowish, black, and white (Figure 5b). Significantly, a fully striped unku is featured in Guaman Poma de Ayala's (Guaman Poma de Ayala et al. Reference Guaman Poma de Ayala, Murra, Adorno and Urioste1980 [1615]) illustration of a provincial administrator (Hughes Reference Hughes2010:Figure 12). Such stripes are also found on textiles from the Formative through the Late periods at Arica and Caleta Vitor (Agüero Reference Agüero2000; Horta Reference Horta2004; Martens and Cameron Reference Martens and Cameron2019; Ulloa Reference Ulloa2008). This does not imply that the CV unku was made locally, however. In the Arica region, there is no evidence for formalized, large-scale craft production, at least up to 600 BP (Cassman Reference Cassman1997:160). Coastal tunics are typically shorter and wider and worn with loincloths, whereas unku are longer (Rowe Reference Rowe1992), further supporting our assertion that the CV unku was imported.

Conclusions

The technical and stylistic characteristics of the CV unku compare so favorably with unku in our database and historical depictions that we conclude it is indeed a prehispanic Inka unku. The checkerboard pattern, rarely seen in viceregal unku, is associated with the Inka military, but the yoke pattern and style are unique. Additionally, this expansion of John Rowe's (Reference Rowe, Rowe, Benson and Schaffer1979) unku database has added important technical, diagnostic characteristics that can be used to identify such iconic garments in the future. Although the CV unku strongly suggests imperial activity, further research is needed into Late period interactions in northern Chile and the suite of artifacts typically associated with the Inka.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Instituto de Alta Investigación of the Universidad de Tarapacá, the China Silk Museum, and Dr. T. Lynch for his valuable comments. Tracy Martens received support from an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and the Chilean National Science Foundation Project 1150763 led by Claudio Latorre. The site map was provided by CartoGIS Services, ANU. We also acknowledge Dumbarton Oaks, the Chicago Field Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and the University Museum of Pennsylvania's Anthropology and Archaeology Museum.

Data Availability Statement

Materials from the Caleta Vitor archaeological complex are housed at the Instituto de Alta Investigación, Universidad de Tarapacá, in Arica, Chile.

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2020.81.

Supplemental Table 1. Unku Database Summary.

Supplemental Table 2. Average Dimensions of Unku.

Supplemental Table 3. Diagnostic Features of Inka Unku.