Sociolegal scholars have long recognized that legal decisions are affected by the wider legal structure and cultural context in which these decisions take place. In fact, it is widely documented that legal outcomes, such as rates of civil litigation, court appeals, availability of post-conviction remedies, guilty pleas, and the nature and severity of criminal sentences, are shaped by aspects of the prevailing legal structure and legal culture (see Reference BlackBlack 1976; Reference Casper, Tyler and FisherCasper, Tyler, & Fisher 1988; Reference Clarke and KurtzClarke & Kurtz 1983; Reference EppEpp 1990; Reference GalanterGalanter 1983; Reference HeumannHeumann 1978; Reference Mather and YngvessonMather & Yngvesson 1980–81; Miethe & Moore 1988; Reference Miethe and MooreMiethe 1987; Reference MietheMusheno, Gregware, Reference Musheno, Gregware and Drass& Drass 1991).

If it is axiomatic that changes in sociolegal conditions affect legal outcomes, it would follow that there would be changes in the nature of legal decisions in Chinese society after the massive economic reforms of the 1980s, especially after the major revisions of the Criminal Procedural Law (CPL) in 1996. The legal reforms codified in the 1996 CPL significantly altered the organization of the Chinese criminal justice system and enhanced defendants' rights in such domains as the right to legal counsel, cross-examination, protections against coerced confession, and appeals (Reference LuoLuo 2000). The growth in legal professionalism and formalism that derives from these changes in legal structure has also been accompanied by changes in legal culture, including the greater acceptance of civil litigation and pursuit of individuals' rights within the legal realm (Reference ChengCheng 2000).

Although China's legal reforms may affect a variety of decisions about civil litigation and criminal processing (see Reference Lu and DrassLu & Drass 2002; Reference Lu and MietheLu & Miethe 2002), they are especially likely to alter the prevalence of criminal confessions and their possible consequences on case disposition. Traditionally, both the legal structure and the wider Chinese culture have actively encouraged, if not almost required, defendants to confess to criminal wrongdoing. After the 1996 legal reforms, the growth in legal protections for criminal defendants, the greater cultural acceptance of individuals' rights, and the increased legal formalism may have produced a sociolegal context in which confession may be less prevalent and less influential on legal decisions. Whether or not criminal confessions have changed in China under this evolving legal environment, however, has not been investigated in previous research.

After a brief description of the social and legal context of confessions in China, the current study uses summary court documents on 1,009 criminal cases to explore the extent, nature, and consequences of confessions on legal decisions. The use of confession and its impact on case outcome is examined within the more general context of communitarian societies. The results of this study are then discussed to elucidate the interrelationships between legal structure, legal culture, and legal decisions within a changing social, economic, and legal context.

Legal Structure, Culture, Confession, and Legal Sanction

The structure of a legal system can facilitate and encourage the use of law by its ease of access to legal resources, fair procedures, and attractive rewards. It can also inhibit the use of law through institutional barriers such as lengthy bureaucratic delays, costly and unfair proceedings, unpredictable outcomes, and/or little financial reward. Legal culture also affects legal decisions because it represents the general attitudes, values, and opinions about law and its use (see Reference FriedmanFriedman 1985; Reference Mather and YngvessonMather & Yngvesson 1980–81). For example, differences in litigiousness in communitarian societies (e.g., Japan, China) and individualistic societies (e.g., the United States) can be partially attributed to differences in legal culture. Mutual obligation, interdependency, and group interests minimize the use of formal law in communitarian environments (see Reference BlackBlack 1976; Reference BraithwaiteBraithwaite 1989; Reference Kawashima and MehrenKawashima 1963), whereas the isolated individual is more likely to resort to legal action in an individualistic society because adjudication is often the only forum for settling disputes in this context (see Reference NaderNader 1969).

Criminal confessions are legal decisions by defendants that are also likely to be influenced by prevailing legal structure and culture. The major legal reservations about confessions in individualistic societies involve an overriding concern for individual rights and the constitutional protections of the accused from coerced and false confessions (Reference McCannMcCann 1998; Reference Leo and OfsheLeo & Ofshe 1998). By contrast, confession in a communitarian context is more likely to be interpreted as the offenders' moral awakening—their readiness to submit to legal authorities, to cooperate with social groups, and to seek reconciliation with the victim and a larger community. Confession with sincere remorse is strongly encouraged in the communitarian context because of its correctional value for the offender and restorative value for society (Reference HaleyHaley 1995). In both individualistic and communitarian societies, however, confession is extremely functional for increasing the efficiency of criminal processing.Footnote 1 When confessions are associated with substantial sentencing concessions for admissions of wrongdoing, they are clearly beneficial to criminal defendants in both types of societies.

The legal response to confessions can also diverge in different legal and cultural contexts. For example, Reference BraithwaiteBraithwaite (1989) argues that higher levels of social integration in communitarian societies allow legal responses to wrongdoing to be more reintegrative, rather than stigmatizing, in regard to their social condemnation. By viewing an offender as a “whole person” who may be reintegrated back into the community, criminal punishments in a communitarian society may be more responsive to the degree of contrition. In fact, Braithwaite's theory of reintegrative shaming suggests that confessors of criminal wrongdoing in communitarian societies who exhibit remorse for their actions would be treated with greater leniency and in a more reintegrative manner (e.g., given probationary sentences or community supervision rather than jail time or imprisonment).

Confessions in a Comparative Context

The nature and consequence of criminal confessions should be influenced by elements of a particular legal structure and culture. However, even within particular communitarian societies, there may be wide variation in criminal confessions and their impact on case disposition. This point is illustrated by a brief comparative analysis of confessions in China and Japan.Footnote 2

China and Japan share many similar features in their social and legal structures. Confucianism helped shape the communitarian foundation for both societies with its emphasis on a hierarchical (e.g., filial piety) order in society, group orientation, and morale, rather than on legal-based behavioral principles (Reference Bodde and MorrisBodde & Morris 1973). These principles locate individuals in a group relational context, where they are perceived by themselves and by others not as individuals but as contextual actors (Reference ChenChen 1973). Loyalty to one's group, rather than insistence on one's rights, are aspects of the legal culture that help produce general attitudes unfavorable to the widespread use of formal legal means of redress. A cultural expectation in both communitarian societies is that individuals should be submissive to legal authorities and exhibit sincerity in their repentance for unlawful actions. Confessions are central components of benevolent paternalism in Japan, designed to teach, humble, and extract contrition from the offender (see Reference FooteFoote 1992). A similar image underlies the legal culture of confession in China.

Another aspect of the legal culture in both societies is the belief that legal authorities will show leniency for confessions. However, there are qualitative differences between Japan and China in terms of whether concessions for confession are codified in the respective legal codes. While Japanese confessors regularly receive significant benefits in sentencing with no explicit promises by law (Reference Ramseyer and NakazatoRamseyer & Nakazato 1999), the Chinese legal system has long institutionalized this legal culture of confession in its penal codes. For example, confession first appeared in legal codes in the Qin Dynasty (221–207 B.C.) and was officially recognized as a mitigating factor in adjudication (Reference Gong and GanGong 1989). The Tang code (625 A.D.) provided the most elaborate rules on confessions and punishments in Imperial China. This code specified the timing of a legal confession and recognized that offenders who confessed to victims should receive the same legal benefits as those who confessed to authorities. The 1979 Criminal Law (CL) and the more recent 1997 Criminal Law (CL) in Socialist China both stipulate a possible lighter (within the sentence range) and/or mitigated (lower than the sentence range) sentence for voluntary confessions (1979 CL Article 63; 1997 CL Article 67).

The legal structures of these societies are also similar in their lack of procedural safeguards for criminal suspects and defendants. Particular procedural limitations that should influence the prevalence and nature of criminal confessions in both countries include the detention of suspects, the right to remain silent, and access to legal counsel.

Police in both countries can detain criminal suspects for a lengthy period of time. In China, police can detain an individual, without access to legal counsel, for up to 40 days before formal charging (CPL Article 69). In Japan, criminal suspects can be detained for a total of 23 days before a decision of whether to indict the suspect must occur (Reference FooteFoote 1992:346).

Defendants' cooperation with law enforcement in criminal investigations is also expected in both countries. In fact, defendants in China do not have the right to remain silent. They are expected to be honest in answering questions from the legal authorities even though they cannot be coerced into admitting guilt (CPL Article 93). In Japan, defendants have the right to remain silent, but they cannot refuse to be questioned (Reference FooteFoote 1992). In both countries, suspects' access to legal counsel is at the discretion of the police and prosecutor (CPL Article 96; Reference FooteFoote 1992). The limited access to legal counsel and the lack of procedural safeguards for detaining and questioning suspects are structural characteristics of criminal processing that strongly encourage confessions in both countries.

However, these two communitarian societies are different in several fundamental aspects of their legal structure and wider culture. First, China has been a socialist system for more than 50 years. Its political ideology has had a profound effect on legal principles, and the law is often used as a tool to achieve political ends. For example, during the 1980s and 1990s, corruption-related offenses were so rampant as to threaten the legitimacy of the Chinese socialist political leadership (Reference Huang and BrahmHuang 2001). To accommodate the need of suppressing these criminal activities, certain clauses within the substantive and procedural criminal laws in China were suspended and offenders were given major incentives, beyond the stipulation of the law, to voluntarily confess to the authorities. Second, China is experiencing dramatic social and cultural changes since the 1980s economic reforms (see Reference Liu, Zhang and MessnerLiu, Zhang, & Messner 2001). Similar social and economic changes have not occurred in Japan over the last two decades.

Legal Changes in China's Post-Reform Era

By all accounts, the economic reforms in China during the 1980s resulted in dramatic social and cultural changes across a variety of domains.Footnote 3 The economic reforms introduced the Western individualist value system that seriously challenged the traditional communitarian values and cultural belief systems in China (Reference Deng and CordiliaDeng & Cordilia 1999; Reference Zhang, Zhou, Messner, Liska, Krohn, Liu and LuZhang et al. 1996). They also precipitated a decline in informal social control at the neighborhood level (Reference Feng, Liu, Zhang and MessnerFeng 2001; Reference Lu, Miethe, Liu, Zhang and MessnerLu & Miethe 2001) and are linked to a transformation of the Chinese citizen from a contextual actor to a self-serving individual actor (Reference Rojek, Liu, Zhang and MessnerRojek 2001). Crime rates in the post-reform period are also at a historical high, resulting in strong public sentiments for greater punitiveness toward offenders (Reference CaiCai 1997).

Changes in values and beliefs in the aftermath of the economic reforms have also affected the legal culture in China. In fact, the Chinese public has increasingly turned to legal redress for dispute resolution in record numbers since the economic reforms. For example, the number of civil disputes adjudicated in courts has nearly tripled between 1988 and 2000 (from 1.2 million to 3.4 million), whereas lawsuits filed against state agencies for unfair or illegal administrative decisions have increased tenfold (from 8,573 cases to 85,760) during this time period (Law Yearbook of China 1988, 2001).Footnote 4 These trends in litigation suggest a major change in legal culture in the post-legal reform era, reflecting an increasing awareness of legal rights and acceptance of adjudication as an alternative for dispute resolution in China.

The economic reforms in the 1980s and the subsequent changes in legal culture were the primary impetus for major revisions in Chinese criminal law in the mid-1990s. Most notable are the sweeping changes made in the 1996 CPL. The 1996 legal reforms, as embodied in the revised CPL, were intended to transform a traditional inquisitorial system of justice into a more adversarial legal process. To achieve this end, the 1996 CPL restricted and defined the power of the police and prosecution in criminal investigations, specified the adjudicative function of the court, and broadened the authority of the defense attorney. For example, related changes in the 1996 CPL involve the practice of custody-for-investigation (CPL Articles 61(7), 69),Footnote 5 the abolishment of the system of exemption from prosecution,Footnote 6 the restriction of the scope of investigation by procuratorates (CPL Article 18),Footnote 7 forbidding conviction to be made without court trials (CPL Articles 12, 163),Footnote 8 the shift of the focus of judges' work from extrajudicial investigations to presiding in courtroom hearings (CPL Article 150), and the enhanced access of defense attorneys in criminal proceedings (CPL Articles 156, 160).

An earlier and more extensive involvement of criminal defense attorneys in criminal proceedings, as stipulated in the 1996 CPL, signified a departure from the traditional inquisitorial system. Indeed, the 1996 CPL allows defense attorneys greater and earlier access to legal documents, more time to prepare for their cases, the opportunity to obtain bail for their clients and to be present during questioning after formal charges have been filed, and the right to cross-examine witnesses.

More effective legal representation has also been possible in the post-1996 reform period because of changes in judicial roles and responsibilities. Specifically, under China's inquisitorial system, judges were required to engage in evidence-gathering and criminal investigations. Judges in the post-reform period, however, should be more likely to serve as impartial adjudicators who hear evidence and arguments from both sides and render a decision based solely on this information. While Chinese law has long recognized voluntary confessions as mitigating factors in sentencing decisions, the new role of judge as adjudicator, not investigator, in the reform era, may have increased the likelihood that the criminal courts will now follow both the spirit and letter of these provisions more closely for more consistent and lenient treatment of confessors.

Post-reform changes in legal structure and legal culture may affect the nature and consequences of criminal confessions in several ways. For example, criminal confessions may decline after the passage of the 1996 CPL because (1) increased legal representation makes criminal defendants more aware of the consequences of their admissions of guilt, (2) changes in legal culture in this large reform environment may have increased public awareness of individual rights and created a cultural climate in which challenges to the state's authority, through nonconfessions, are more socially acceptable, and (3) burden of proof requirements may have increased dramatically under a more adversarial system, leading potential confessors to be less inclined to contribute directly to their own conviction through self-incrimination. Similarly, confessions in the post-reform era may have a greater impact on case disposition because the concessions for admissions of guilt are more clearly articulated in the revised legal codes, and the presence of a defense counsel may help ensure that the benefits of contrition are actually granted to the defendant.

It is also possible, however, that the socioeconomic and legal reforms in China in the last two decades have had a minimal effect on the nature and consequences of criminal confessions. For example, confession rates may remain high in the post-1996 reform period under two related conditions: (1) communitarianism and collective values that encourage confessions have persisted as strong cultural imperatives in China even in the post-reform period, and (2) sociolegal changes thought to decrease public pressure for criminal confessions (e.g., the rise in individual rights and the presumed greater acceptance of challenges to the state's authority) are just secondary cultural themes that may actually affect only a small minority of Chinese citizens. In addition, China's legal changes may be more indicative of symbolic reform than actual changes in criminal processing. Similar to symbolic reform efforts in other substantive areas in Western societies (e.g., gang legislation, prohibition, “three strikes” legislation), external forces (e.g., media attention, human rights groups) may have initiated formal changes in legal culture and law in China, but these legal provisions may be easily circumvented in actual practice. Under these conditions, little change in the nature and consequences of criminal confessions would be expected in the post-reform period.

Given these conflicting views regarding the impact of social and legal changes on legal decisions, it is unclear whether the nature and consequences of criminal confessions have changed in China's post-legal reform era. Criminal confessions are a key element of communitarian societies and their emphasis of collective values, reintegrative shaming, and restorative justice. The absence of procedural safeguards for criminal defendants (e.g., lack of legal representation, inquisitorial systems of justice) is the type of legal structure that seems to foster higher levels of criminal confession. Nonetheless, the key empirical question is whether changes in these aspects of legal culture and legal structure are associated with changes in the prevalence and legal consequences of confessions.

Research Questions

Given these significant social, cultural, and legal changes in China, this study examines two interrelated questions about criminal confessions. First, how often are confessions given in the current Chinese context, and have rates of confession decreased since the 1996 legal reforms? Second, what is the net impact of confession on criminal court dispositions, and has the impact of confession on these decisions changed over time?

Methods

Data Sources

The primary data for this study were derived from a sample of 1,009 summary court documents across China. These court cases include major forms of criminal activities (e.g., violent, property, and white-collar offenses), and cover 29 of the 30 provinces in China (data from Tibet were not available). The cases were tried between 1986 and 2001, encompassing three levels of Chinese courts (i.e., district, intermediate, and superior courts).

We drew our sample of 1,009 cases from seven published collections of criminal court cases (a list of these collections is included in Appendix A). Each book describes the process of case selection for inclusion. The language used by the editors of these collections gives some indication of the basis for selection. For example, a regional sample of cases included in the 2000 Shanghai Case Collection is stated to be “carefully selected.” The cases cover “a broad range of areas” and are “typical” of each type of case (Qiao 2000:1). A national sample of criminal cases put together by the Institute for Applied Legal Studies of the Supreme Court was meant to reflect emerging and changing crime patterns and behaviors. This collection tends to focus on serious cases, cases involving individuals of high status, and cases involving complex facts and laws (Cao 2000). By contrast, the collection compiled by the College of National Judge and the Chinese People's University was designed to “provide useful information for legal scholars and practitioners” (Zhu 1999:1). Therefore, maintaining “authenticity and objectivity” were two of the major goals (Zhu 1999:1). Cases were selected particularly for their representation of the time when they were adjudicated, as both crime and definition of crime may be changing over time (Zhu 1999).

As a result of the different bases for inclusion in a particular collection, it is difficult to gauge the overall representativeness of these data to all criminal cases in China. As a group, these national criminal cases cover more serious offenses than is probably true of general criminal offenses in China. This is indicated by the large proportion of cases in the sample that involved serious property loss/damage or physical injury, prison sentences upon conviction, and sentences as severe as “life” and “death” (see Table 1). The description of cases in the collection documents also suggests that these criminal offenses were probably more complicated and of greater national interest than the typical criminal offense.

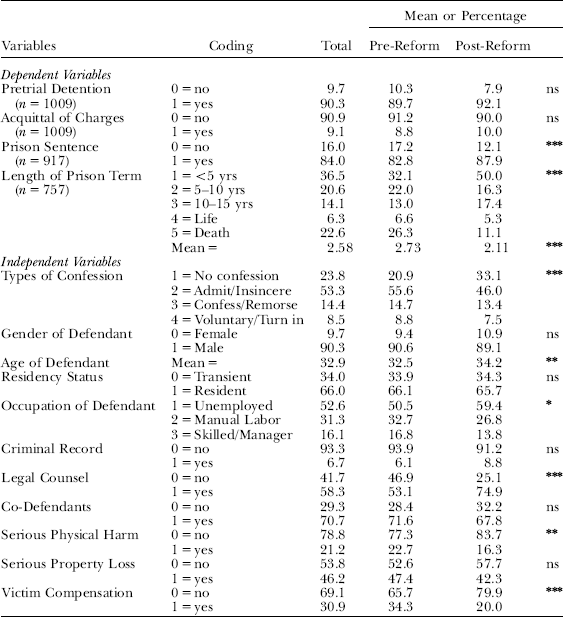

Table 1. Coding of Variables and Frequency Distribution Before and After Legal Reform

Notes: ns=nonsignificant difference;

* p<0.10;

** p<0.05;

*** p<0.01.

The descriptive documents do not indicate whether or not confession was a basis for case selection in these published collections. This is important because it eliminates a type of sample selection bias as an explanation for possible changes in confession rates over time.Footnote 9 We used statistical control through multivariate analyses to evaluate the impact of other sources of sample differences over time (e.g., the inclusion of more serious offenses, offenders with more serious criminal records, or cases with high rates of legal representation in the post-reform sample) on our substantive conclusions about changes in the likelihood of criminal confessions in the post-reform period.

Although the nonrandom inclusion of cases into the various collections restricts the generalizability of our findings, the overall sample of 1,009 cases is sufficiently diverse to provide a preliminary assessment of the extent, nature, and consequences of confessions on case disposition within a changing legal environment in China. It is within this context that we describe our empirical findings as primarily exploratory.

Variable Coding

We call court case documents in this study summary judgments. A presiding judge or a panel of judges prepares these documents after a case is closed. Summary judgments are the official formal record of the court proceedings, and their structure and content are similar to a pre-sentence investigation report (PSI) in U.S. felony cases. These documents include descriptive narrative summaries of the court proceedings and detailed information about the offender (e.g., age, gender, employment status, occupation, education, type of confession given, legal representation, prior criminal record), the offense (e.g., offense severity, co-offending pattern), and case processing outcomes (e.g., pretrial detention, acquittal or convictions, and sentencing decisions). Table 1 presents the coding of the variable and frequency distributions associated with them for each time period.

The primary variable in this study involves the nature of the offender's confession. The measure of confession involves four categories that derive from the depictions of offenders' attitudes and the court's reactions, which are presented in the summary judgment documents. Given that both the offenders' actual admissions of guilt and their attitude (e.g., contrition, sincerity) are legally relevant factors in case disposition, we included this information about confessions explicitly in all 1,009 cases of the summary judgments.

The first category of confession includes offenders who refused to admit any criminal wrongdoings (juburenzui—refusal of admission of guilt). This type of confession is illustrated in the summary judgments by particular wording that states explicitly that the defendant refused to admit guilt and thus deserved more severe punishment. When we treated confession as a simple dummy variable, we used this category to define nonconfessors.

The second category of confession refers to those who admitted to their crime after being arrested, but their admission was interpreted by legal officials as incomplete, nonspontaneous, insincere, or instrumental in nature (e.g., confessing to receive a reduced sentence). This type of confession is called renzui (i.e., “admission of guilt”). A typical narrative statement that reflects this type of confession is “the offender admitted the charges—his attitude was ‘so-so’” (case #90). Consistent with the traditional sentencing practice in China, judges generally make no specific comments about either lenient or severe punishment for these “marginally sincere” confessions.

The third category includes offenders who confessed to their crime after the police discovered their major criminal activities but showed sincere remorse and repentance (tanbai—confession). In some cases, those offenders also apologized to the victim and made restitution. According to the longstanding Chinese legal tradition for treating remorseful confessors with leniency, judges have discretion in granting lenient punishments for these offenders. Some Chinese scholars even argue that laws should explicitly reward those individuals who confess remorsefully, even after their capture, in order to educate the public of the importance of remorse and conformity with the social norms (Reference Li and XieLi & Xie 2000). In coding this type of confession, we looked for the following types of comments in the summary judgments: (1) “the offender's attitude is good” but with no explicit comments of lenient case disposition (case #869), (2) “the offender's attitude is good and deserves lenient punishment” (case #295), and (3) “after her capture, the offender admitted the wrongdoing and showed sincere remorse—she also compensated the victim's loss [and] thus deserves lenient treatment” (case #125).

The fourth category of confession involves offenders who voluntarily turned themselves in before the officials discovered their wrongdoings (zishou—literally, self-submission). These offenders, according to the 1997 CL (Article 67), represent the highest degree of confession and, by law, qualify for a lighter or mitigated sentencing reduction. In these types of cases, the court's language is quite uniform that “the offender voluntarily turned himself in, qualifying for zishou by law, thus should receive reduced sentences” (e.g., case #123).

Other legal variables that are mandated to influence court decisions under Chinese law include offense severity, prior record, and co-offending pattern. We measured offense severity by two dummy variables: (1) whether there was serious physical harm to the victim (coded “yes” or “no”) and (2) whether there was serious damage or loss of property (coded “yes” or “no”).Footnote 10 The excluded category in this coding scheme represents cases in which there was no serious physical injury or property damage/loss. We also dummy-coded prior record to represent whether the defendant had a prior criminal conviction. We coded co-offending patterns to contrast offenses with and without multiple offenders. Crimes involving multiple offenders are considered more serious in China because of the greater planning and the treatment of these offenses as criminal conspiracies (Reference Zhang and MessnerZhang & Messner 1994).

Extralegal factors involve offender and case attributes that are not legally mandated to influence case disposition. These factors include characteristics of the defendant (e.g., age,Footnote 11 gender, occupation, and residency status) and offense or case attributes (e.g., victim compensation by the offender or the defense attorney used in the case). We measured occupation as an ordinal variable, ranging from the unemployed, manual laborers (e.g., clerks, factory workers, self-employed laborers), and high-status offenders (e.g., managers and governmental officials). Residency status referred to whether an individual was a permanent resident or recent migrant to the area where he/she committed the crime. We also dummy-coded the year of the criminal case to compare types of confessions and case dispositions before and after the 1996 legal reform.

While age, gender, occupation, and legal representation have been regularly used in assessing legal decisions in both Western and Chinese studies (Reference Liu, Zhou, Liska, Messner, Krohn, Zhang and LuLiu et al. 1998; Reference Liu, Zhang and MessnerLiu, Zhang, & Messner 2001; Reference Lu and MietheLu & Miethe 2002; Reference MietheMiethe 1987; Reference NagelNagel 1983; Reference Zhang, Zhou, Messner, Liska, Krohn, Liu and LuZhang et al. 1996), residency status and victim compensation by the offender are unique in China. Because transients are increasingly blamed for urban crimes in China, they are expected to be treated more harshly by the criminal justice system. Victim compensation by the offender signifies reconciliation and restoration in the communitarian cultural tradition. Previous studies have found that compensation made by the offender significantly reduces the severity of punishment (Reference Lu and DrassLu & Drass 2002).

We include several measures of legal process and case disposition in this study as dependent variables. These include separate dummy variables that represent whether the defendant confessed to the crime (confession), received pretrial detention or bail (detention), was acquitted or convicted of the charge (acquittal), or received a prison sentence upon conviction (prison). We measured the length of the sentence on an ordinal scale, including the following categories: (1) less than five years of incarceration, (2) more than five and less than ten years of incarceration, (3) between ten and fifteen years of imprisonment,Footnote 12 (4) life imprisonment, and (5) the death penalty.

Results

We conducted two general types of analyses to examine the extent, nature, and consequences of confessions on criminal case disposition. First, we explored the univariate frequencies for different types of confessions and the other variables for the general sample and within each time period before and after the legal reform in 1996. Second, we conducted multiple regression analyses to explore (1) whether differences in the likelihood of confessions over pre- and post-1996 reform periods would hold after controlling for differences in offender and case attributes across samples, and (2) the net impact of confession on criminal court decisions once we introduced controls for other legal and extralegal factors. We added interaction effects between confession and time period to these latter regression models to assess the nature and magnitude of context-specific effects of confessions on case outcome. The results of these analyses are summarized below.

Univariate Frequency Distributions

Our primary interest involves the nature of criminal confessions, and our sample data suggest that the extent and nature of confessions have changed over time. As shown in Table 1, the proportion of Chinese defendants who refused to admit their guilt significantly increased over time (from 21 to 33% of the cases in the post-reform period), and the proportion who confessed but were considered to be insincere in their remorse dropped from 56 to 46%. The other two types of confessions (i.e., confession with remorse and defendants who turned themselves in voluntarily for their crimes) remained relatively stable over time and were relatively rare within this sample of criminal cases.

Concerning criminal case disposition, approximately 90% of the defendants in the sample were detained prior to trial, and this proportion did not significantly change over time. Only about 9% of the defendants in each period were acquitted of all charges. The proportion of convicted defendants given a prison sentence increased from 83% in the pre-reform era to 88% in the post-reform period. The length and severity of the prison sentence for these defendants were significantly reduced after the legal reform in 1996. Half of the convicted defendants received less than five years of imprisonment in the post-reform period, compared to only about one-third of the pre-reform defendants. The proportion of criminal cases that involved a death sentence was more than twice as large in the pre-reform period as in the post-reform period.

Of the offender and case variables, there were significant changes over time in the age and occupation of the defendant, legal representation, seriousness of physical harm, and victim compensation. These results indicate that offenders in the post-reform period were older and more likely to be unemployed and represented by counsel than their counterparts, and the offenses were less likely to involve physical injury or death, than in the pre-reform era. The proportion of criminal cases involving male offenders (90%), local residents (66%), defendants with criminal records (7%), co-defendants (71%), and serious property loss/damage (46%) did not significantly change over time.

Predicting the Likelihood of Confessions

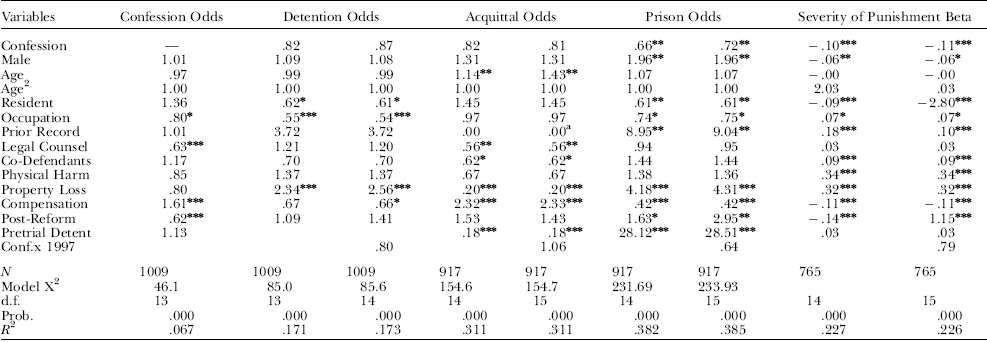

Given that confessions are significantly less common in the post-reform era, an important question involves whether or not these differences persisted after we introduced controls for differences in offender and case attributes across the samples. Table 2 summarizes the results of this multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Table 2. Logistic and Multiple Regression Analysis of Confessions, Pretrial Detention, Acquittal, Prison Sentence, and the Severity of Punishment

a Notes: This small value represents that all defendants with a prior record in the post-reform period were convicted. d.f. represents the degrees of freedom.

* p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

The likelihood of a defendant's confession has decreased in the post-reform period, and this pattern held in both the bivariate and multivariate analyses. When we introduced statistical controls for offender and case attributes, the conditional odds of a confession were 1.6 times less likely after the legal reforms. This finding of a significant net reduction in the odds of confession in the post-reform era provides more direct support for the claim that the procedural reforms in the criminal law were associated with a decreased willingness of criminal defendants to admit their guilt. Among the offender and case attributes, the likelihood of a confession was significantly higher, ceteris paribus, for defendants who were residents of the particular jurisdiction, unemployed, not represented by counsel, and who provided the victim compensation. The finding that legal representation was associated with a net decrease in the probability of confession is consistent with the assertion that access to legal counsel provides criminal defendants some legal protection and safeguard against unbridled pressures toward admissions of guilt and self-incrimination. Inclusion of an interaction term to represent whether legal counsel had context-specific effects (e.g., if counsel was more influential on confession decisions in the post-reform era), however, was nonsignificant, indicating that the legal counsel had a similar effect on reducing the likelihood of confession in both the pre- and post-reform periods.

The Impact of Confession on Criminal Case Disposition

We examined the impact of confession on criminal processing decisions by comparing nonconfessors and various types of confessions. We conducted both bivariate and multivariate analyses to explore these relationships.

About 90% of the defendants in this sample were detained pending trial, and there were no significant differences between confessors (91%) and nonconfessors (90%). Among the types of confessors, however, the proportion of defendants detained before trial was lower for those who showed remorse (83%) or voluntarily confessed to undetected criminal activity (84%) than for those whose admissions were considered less than sincere (94%).

Nonconfessors had a higher rate of acquittal on all criminal charges than confessors with insufficient sincerity (14% vs. 5%), but acquittal rates for other types of confessors were similar to those for nonconfessors.Footnote 13

An examination of the bivariate relations revealed a significant difference between nonconfessors and confessors in the likelihood of receiving a prison sentence upon conviction. While about 95% of nonconfessors received a prison sentence upon conviction, only about 81% of confessors received a prison sentence. Among the different types of confessors, the likelihood of a prison sentence was lowest among defendants who turned themselves in (69%) or confessed with remorse (73%), whereas imprisonment risks were much higher (85%) among confessors whose sincerity was challenged by court officials. Nonconfessors were also given more severe prison sentences and punishments than confessors. For example, nearly one-third of convicted offenders who did not confess were given a death sentence, compared to less than one-fifth of the confessors. Defendants who admitted guilt without sufficient remorse were given the most severe punishments among the different types of confessors.

Some of the bivariate relationships between confession and case disposition persisted, while others changed after we introduced controls for other offender and case attributes through multivariate analyses. As shown in Table 2, logistic regression analyses revealed that confession had no significant net impact on the likelihood of pretrial detention and acquittal/conviction decisions. Similar to the bivariate results, confessors were less likely to receive a prison sentence and were given significantly shorter and less severe prison sentences than nonconfessors after controlling for other variables.

Aside from the impact of confessions, criminal case dispositions in this sample were also influenced by several offender and case attributes. For example, the conditional odds of pretrial detention, ceteris paribus, were significantly higher among migrants, the unemployed and less-skilled workers, and offenses involving serious property loss/damage. The net likelihood of receiving an acquittal of all charges was significantly higher among older defendants, persons not represented by counsel, single offenders, those charged with less serious property offenses, defendants who compensated victims, and individuals who were not detained before trial. The conditional odds of a prison sentence were higher among male offenders, migrants, unemployed and less-skilled workers, offenders with prior records, serious property offenses, defendants who did not compensate victims, and those defendants who were detained prior to trial. Finally, the multiple regression analysis indicated that more severe punishments were given to female defendants, migrants, those of higher occupational status and prior records, crime situations involving multiple offenders, serious physical and property crimes, and noncompensators of crime victims.

Context-Specific Effects of Confession on Case Disposition

Although the legal stipulation of sentencing reductions for voluntary confessors has remained the same over the last two decades, judicial discretion in criminal processing decisions may still have been affected by other changes in legal structure and legal culture after the 1996 legal reforms.

To explore more fully whether the impact of confession on case disposition is context-specific (i.e., dependent upon time period), we entered interaction terms into the respective logistic regression and multiple regression models to determine whether these outcomes were significantly different after the legal reforms. As shown in Table 2, these interaction effects were not significant for all of the dependent variables, suggesting that the net impact of confession on case disposition did not change appreciably after the reform effort. Overall, the multivariate analysis indicated that differences between confessors and nonconfessors in case outcomes are similar in both the pre- and post-legal reform periods in China.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our study reveals two important findings about confessions and legal sanctions in China. First, while the majority of criminal defendants in this sample confessed to their crimes, confessions were less frequent after the legal reform in 1996. Second, confessors received more favorable case dispositions than nonconfessors, and this pattern held for both the pre- and post-reform periods.

Before examining the substantive importance of these findings, it is important to note that our estimates of the prevalence of criminal confessions at each time period are necessarily tentative due to the limitations of the sampling design (e.g., cases included in the published collections are more serious than typical criminal cases in China). However, the observed decline in confessions in China's post-reform period is not simply a methodological artifact of some type of sampling biases because (1) the criteria for including cases in the published collections have not changed over time; and (2) lower confession rates were found in the post-legal reform period even after statistical controls were introduced for offender and offense differences across samples (see Table 2). Under these conditions, the findings have several implications for the general study of legal decisions within a changing sociolegal context. We examine substantive explanations for the current findings and the implications of these results for further comparative research below.

Explaining the Decline in Criminal Confessions

The major economic reforms in the 1980s had a profound impact on Chinese society. They introduced a Western value system that seriously challenged traditional communitarian values and cultural beliefs. The common Chinese citizen experienced a personal transformation from a contextual actor (i.e., a person whose identity is linked to a group or relational context) to a self-serving individual actor. These social forces, in turn, precipitated declines in informal social control that have been linked to unprecedented increases in crime rates and strong public outcry for more punitive measures toward offenders. Subsequent changes in legal structure (e.g., increased legal counsel, more adversarial proceedings) and legal culture (e.g., greater use of law for dispute resolution, more formal challenges to state authority) occurred following the initial economic reforms.

Although it is relatively simple to document these social and legal changes in China, it is far more difficult to identify the major contributor to the decline in criminal confessions over time. Possible explanations for decreases in confessions in the post-reform period include (1) declining communitarian values, (2) changing legal structure, (3) changing legal culture, and (4) basic changes in cost/benefit evaluations of confession by criminal defendants. We summarize the strengths and limitations of each explanation below.

Any viable explanation for declining confession rates in China's post-reform period must begin with the decline in the communitarian value system. Communitarian societies are linked to particular functional imperatives (e.g., mutual obligations, interdependency, and group interests superseding individual interests) that promote confession as morally appropriate behavior necessary for the restoration and reintegration of the “whole person” back into his/her social group. While communitarianism remains the dominant value system in China, individualism has continued to grow in China over the post-reform period.

Rising self interest under declining communitarianism, however, cannot itself explain the decline in confessions unless concurrent changes have also occurred in legal structures. This is the case because elements of the prevailing legal structures (e.g., access to legal counsel and other resources, individual rights) place serious constraints on defendants' opportunities to confess. Without a facilitating legal structure, a defendant's desire to fight the allegations through nonconfession is neither a practical nor a feasible option.

Various changes in the legal structure have occurred in the post-legal reform period, but the most visible change involves the greater access to legal counsel. In fact, the broadened rights to legal representation are the major source of change in China's legal structure because other changes in procedural law (e.g., the movement away from an inquisitorial system, more adjudicative functioning by judges, increased defendants' rights to cross-examining witnesses, and pretrial release) are directly tied to access to defense counsel. Aside from providing basic legal protection for their clients, legal counsel may enhance defendants' awareness of the consequences of their admissions of guilt, thereby reducing their likelihood of confession. The presence of legal counsel may also increase the chances that sentencing concessions will be granted if defendants do confess. However, the rise in legal representation is not a sufficient explanation for the declining rates of confession because we found lower risks of confession in the post-reform era even after we included statistical controls for differences in legal representation across pre- and post-reform samples. This latter finding suggests that it is more than just the availability of defense counsel that precipitated the decline in criminal confessions.

Changes in legal culture that may explain the post-reform decline in criminal confessions involve the consequences of increased acceptance and use of litigation. As mentioned earlier, there has been a dramatic increase in civil litigation in China over the last two decades. One possible consequence of this increased use of law to resolve civil disputes is greater public awareness of individual rights and the subsequent emergence of a cultural climate in which nonconfession is becoming a more socially acceptable challenge to the state's authority. However, a legal culture conducive to nonconfession behaviors also requires a facilitating legal structure that provides defendants the physical opportunity to challenge the longstanding tradition of confession in China's legal history.

Another plausible explanation for defendants' greater reluctance to confess in the post-legal reform era perhaps lies in pragmatic concerns about the lack of certainty of dispositional decisions and the harsh punishments defendants are likely to receive after they have confessed. These concerns about the “costs” and “benefits” of confession fit into a more general rational choice framework that views legal actors as rational decision makers (see Reference RamseyerRamseyer 1985, Reference Ramseyer1988).

From this rational choice perspective, confession decisions reflect a rational calculation of the relative risks and benefits of confession. Potential benefits of confession for the defendant include the possibility of a reduced sentence for confession and positive appraisals of his/her moral worth by following the traditional cultural imperative that associates confession with “good citizenry” and as being necessary for the moral reform of the offender. The primary costs of confession involve the greater certainty of a criminal conviction and a virtual guarantee of severe punishment even if the defendant confesses when the initial charge is serious.

Several aspects of the Chinese legal system, however, make these cost/benefit calculations more difficult than in other contexts. For example, plea agreements in the United States are a type of confession that clearly specifies a particular concession for the guilty plea (e.g., a charge reduction, dismissal of other counts, probation rather than jail time, concurrent rather than consecutive sentences). In China, however, confession in most cases does not guarantee a concession. Instead, the criminal code and the penal policy in China only specify that persons who confess with sincere remorse or before the police detect the crime will be given a more lenient sentence (but the degree or amount of leniency is not defined). In addition, the code and policy allow judges to easily circumvent provisions for lenient treatment through their official interpretations of the sincerity of the defendant's confession. Chinese defendants are also disadvantaged in these risk/benefit calculations because of (1) an enormous variability in sentencing for most offenses,Footnote 14 (2) less public awareness of the “going rate” for particular crimes and greater uncertainty that these “standard” sentences would be applied even if known, (3) high prospects for severe punishments for many defendants even if they confess,Footnote 15 (4) less access to defense counsel for protecting defendants' rights, and (5) less advocacy by those who have legal representation than is true of most Western developed countries. Sound cost/benefit calculations under these conditions of uncertainty are extremely difficult.

From the perspective of the rational legal actor, the high rate of confession in both the pre- and post-reform periods must be attributable to an excess of perceived benefits, whereas the post-reform decline in confessions must be due to a change in the nature of these cost/benefit ratios. Because these cost/benefit calculations should derive from rational defendants' assessments of the prevailing social and legal conditions, this explanation for the post-reform decline in criminal confessions is also ultimately tied to the nature of legal structure, legal culture, and the wider social context in which these decisions are made.

Collectively, these interpretations suggest that the post-legal reform decline in confessions in China is not the direct consequence of any singular factor. The additive combination of all of these social forces is also not an adequate explanation for this finding because even though confessions have declined over time, they still remain the dominant trend in about two-thirds of the criminal cases in the post-reform sample. Instead, it is the particular conjunction of a changing value system and legal cultures, legal structures, and modifications in the subjective calculations of a cost-benefit ratio that best account for the observed decline in criminal confessions in the post-legal reform period.

For those concerned with the general study of law and society, these explanations for declining confessions in China's post-legal reform period suggest that this basic relationship between social and legal change is both complex and dynamic. It is not simply an additive combination of particular events in isolation. In fact, even when the temporal ordering between social and legal change appears to be relatively straightforward, the lingering effect of cultural traditions similar to China's communitarian value system may continue to influence legal decisions, even within a rapidly evolving sociolegal context. An immediate question for further research that derives from the current study is whether declines in criminal confessions will become more apparent in China as its communitarian foundation and legal structure continue to change over time.

The Consequence of Confession on Case Outcome

It is widely known that sanctions rendered by the criminal justice system can be very severe in China (Reference CaiCai 1997). Consistent with the literature, the current study reveals that most offenders were detained during investigation and trial (90%), were convicted (91%) and given a prison sentence (84%), and received lengthy imprisonment terms (approximately 64% of offenders who received a prison sentence served longer than five years). Once controls were introduced for offender and offense characteristics, whether or not a defendant confessed had no significant impact on the likelihood of pretrial detention or conviction decisions. However, confession had a significant net impact on reducing the punishment for convicted offenders. Confessors were significantly less likely to get a prison sentence and were given less harsh punishment if they received a prison term.

While confession was associated with less severe punishment in both the pre- and post-reform periods, the fact remains that Chinese defendants still face harsh punishments even when they do confess. For example, 85% of the confessors in the post-legal reform period were still given a prison sentence upon conviction, and nearly one-third of them received punishments more severe than ten years in prison. In considering that confessions had similar effects on sentencing decisions over time (see Table 2), these findings suggest that sociolegal changes in the reform period did not “spill over” and differentially affected the consequences of confessions. Regardless of the time period, it is clear from these findings that Chinese defendants in this sample did not reap the same type of sentence concessions for their admissions of guilt as defendants in criminal court proceedings of other countries.

From the Western perspective on plea bargaining, it is an interesting and relatively unique dynamic that confession in China's post-legal reform period remains the dominant “choice,” and criminal defendants receive comparatively little benefit in sentencing concessions for their admissions. However, this particular pattern appears to be explained by the continued restrictions on individual rights,Footnote 16 the steadfast faith by lawmakers of the probative value of confession, and/or China's communitarian tradition that places more importance on the moral value of confession than its subjective utility to the offender as a means of receiving a more lenient punishment.

Implications for Comparative Research

A comparison of confessions and their impact on case disposition between the Chinese and the Japanese system reveals that an overwhelming majority of criminal defendants confess to legal authority about their criminal involvement in both countries (Reference Ramseyer and RasmusenRamseyer & Rasmusen 2001). As discussed previously, the strong inclination toward submission to authorities by individuals in these two societies may lie in the Confucian cultural influence that stressed a group-oriented, hierarchically, and morally ordered society. These essentially communitarian societies have produced a different system of confession from that practiced in an individualistic society. While plea bargaining in the United States is functionally equivalent to the system of confession in Japan and China in that they both help reduce the severity of legal sanctions and save resources for the criminal justice system, plea bargaining is fundamentally different from confession. Plea bargaining focuses on the probative value of confessions. In contrast, the corrective value of confessions is more emphasized in both of these communitarian societies.

While the Japanese society has remained true to its core belief and values about communitarianism, the changing economic, social, and legal arrangements in China, accompanied with greater changes in the culture system, signify a major departure from its communitarian roots to a more individualistic society. As we have suggested earlier, these structural and cultural changes may ultimately underlie the reduced confession rate in China in recent years. Major changes in Japan's confession rates may not have occurred because similar changes in the legal structure and its culture have not taken place (Reference Sanders, Jacob, Blankenburg, Kritzer, Provine and SandersSanders 1996).

Although it is both structurally and culturally expected that confessions receive leniency in China and Japan, the degree of leniency does not appear to be comparable in the two systems. Japanese criminal defendants receive much more lenient sanctions than their Chinese counterparts. Compared to our Chinese sample, Japanese defendants are more likely to be convicted, but the overwhelming majority of those convicted receive a suspended sentence. Among those who are convicted and receive a nonsuspended sentence, the majority of sentences are less than five years (Reference BayleyBayley 1991; Reference ReichelReichel 2002).

In addition to the major differences in the changing nature of confession and the legal responses to confessions between the two systems, there are some notable differences with regard to how confessions are conducted in these two societies. For example, compensation is “ordinarily done” in Japan (Reference HaleyHaley 1995:130), but only a small proportion of our Chinese offenders (31%) compensated the victim. Japanese offenders are also expected to apologize to the victim and seek their forgiveness, but no such expectation exists in China. Of all the 1,009 cases, in only four cases did the court comment that defendants made compensation and apologized to the victims and their family. Furthermore, victims and/or their family members play an important role in the criminal justice proceeding with letters of forgiveness in Japan (Reference HaleyHaley 1995). This contrasts with little victim involvement in the Chinese legal system. In fact, there was no mention of the victim's views about the defendant and/or the offense in any of the official Chinese court records examined in this study.

The differences in the practice of confession between the two societies may lie in the Chinese socialist legal system, which departs from the communitarian legal culture. While the communitarian society emphasizes the mediation of the relationship between individuals, a socialist system tends to focus on the maintenance of state and individual relations (Reference Sanders and HamiltonSanders & Hamilton 1992). For this reason, an apology to the victim symbolizes the restoration of individual relationships in a communitarian context, whereas admission of guilt to legal authorities represents the restored order between the state and the individual in socialist China. In either context, however, confession plays an important role in case disposition. How rates of confession will respond to further sociolegal changes in both societies remains an interesting question for future research.

Appendix A: List of Case Collections

Cao, Jianming (2000) Renmin fayuan anli xuan 1992–1999 [Selected Cases from the People's Courts—1992–1999]. Beijing: China Law Publishing House.

Qiao, Xianzhi (2000) 2000 Shanghai fayuan anli jingxuan [Selected Court Cases in Shanghai—2000]. Shanghai: Shanghai People's Publishing House.

Zhang, Buyong (2000) Beijing haidianqu renmin fayuan shenpan anli xuanxi—1999 [Selected Cases from Haidian District Court of Beijing—1999]. Beijing: The Chinese University of Law and Politics Publishing House.

Zhu, Mingshan (1994) Zhongguo shenpan anli yaolan—1993 xingshi anli juan [Selected Chinese Criminal Court Cases—1993]. Beijing: Chinese University of People's Public Security Publishing House.

Zhu, Mingshan (1995) Zhongguo shenpan anli yaolan—1994 xingshi anli juan [Selected Chinese Criminal Court Cases—1994]. Beijing: Chinese University of People's Public Security Publishing House.

Zhu, Mingshan (1998) Zhongguo shenpan anli yaolan—1997 xingshi anli juan [Selected Chinese Criminal Court Cases—1997]. Beijing: Chinese People's University Publishing House.

Zhu, Mingshan (1999) Zhongguo shenpan anli yaolan—1998 xingshi anli juan [Selected Chinese Criminal Court Cases—1998]. Beijing: Chinese People's University Publishing House.

Appendix B: List of Substantive and Procedural Criminal Law Articles Cited and Titles

“The 1979 Criminal Law of the People's Republic of China,” provided by Chinalaw, computer-assisted legal research center, Peking University.

Luo, Wei (1998) The 1997 Criminal Code of the People's Republic of China—With English Translation and Introduction. New York: William S. Hein and Co., Inc.

(2000) The Amended Criminal Procedural Law and the Criminal Court Rules of the People's Republic of China: With English Translation, Introduction, and Annotation. New York: William S. Hein and Co., Inc.

1997 Criminal Law

Article 45: The Term of fixed-term imprisonment shall not be less than 6 months nor more than 15 years.

Article 67: Where anyone who voluntarily gives himself up to the authorities after committing a crime and gives a true account of his criminal activities, his action is regarded as an act of voluntary surrender. Criminals who voluntarily surrender may be given a lighter or mitigated punishment. Those whose crimes are relatively minor may be given a mitigated punishment or be exempted from punishment.

1996 Criminal Procedural Law

Article 12, Innocent Until Proven to Be Guilty: No one shall be convicted without a verdict rendered by a people's court according to the law.

Article 18, Cases Shall Be Investigated by Procuratorates: The people's procuratorates also may investigate other major criminal cases committed by state functionaries who abuse their offices if these cases need to be directly handled by the people's procuratorates and they are so decided by the people's procuratorates at or above the provincial level.

Article 61, Circumstances for Detention: In any of the following circumstances, the public security organs may detain an offender who is committing a crime or a person who is a prime suspect.

(7) if he is a prime suspect who goes from place to place committing crimes, who repeatedly has committed crimes, or who colludes with a gang to commit crimes.

Article 69, Arrest Request After Detention: For those detainees for whom the public security organ determines arrest, the public security organ shall submit the arrest warrant application to the people's procuratorate for review and approval within three days after the detention. Under special circumstances, the time limit on submitting the application for review and approval can be extended for one to four more days.

For those prime suspects who go from place to place committing crimes, who have repeatedly committed crimes, or who collude with a gang to commit crimes, the time limit of submitting the application for review and approval can be extended for up to thirty days.

Article 93, General Questions for Interrogation: When interrogating a criminal suspect, the investigative functionary first shall ask whether the suspect has engaged in any criminal conduct and let him state the circumstances and events of guilt or his innocence, and then ask him other questions. A criminal suspect shall truthfully answer the questions raised by an investigative functionary based on facts, but he has the right to refuse to answer the questions which are not relevant to the case.

Article 96, Time to Retain Counsel and Counseling: After receiving the first interrogation from an investigation organ or from the day of receiving a compulsory measure, the criminal suspect may retain a lawyer to provide him with legal advice, to represent him to file a complaint, or to make an accusation on his behalf. A criminal suspect who is arrested may retain a lawyer to file an application for obtaining a guarantor for awaiting trial out of custody while he awaits a trial. In cases involving state secrets, the lawyers retained by criminal suspects shall be approved by the investigating organ.

A retained lawyer has the right to know the offense to which the criminal suspect is accused, and interview the detained criminal suspect to understand the circumstances and details related to the case. When a lawyer interviews his client, a criminal suspect, the investigating organ may, depending on the circumstances and necessities, send its own functionary to be present in the interview. In cases involving state secrets, the lawyer's interview with the detained criminal suspects shall be approved by the investigating organ.

Article 150, Decision to Commence a Court Session: After conducting an examination of a case in which a public prosecution has been initiated, the people's court shall decide to commence a court session to try the case if the indictment clearly states the facts of accused crimes and attaches the catalog of evidence, the list of witnesses, and duplicated photocopies or pictures of major evidence.

Article 156, Notifying Witnesses of the Legal Obligation: When a witness is testifying, the adjudicators shall inform him to testify based on the facts and the legal obligation that he will bear if he intentionally provides false testimony or conceals criminal evidence. With the permission of the chief judge, public prosecutors, the parties, defenders, or litigation attorneys may cross-examine the witnesses and expert witnesses. If the chief judge determines that the content of cross-examination is irrelevant to the case, he shall stop it. The adjudicators may question witness and expert witness.

Article 160, Presenting Opinions, Rebuttal, and the Right of an Accused to Make a Final Statement: With the permission of the chief judge, the public prosecutors, and the parties, the defenders, or the litigation attorneys may present their opinions about the evidence and the circumstances of the case, and rebut each other. After the chief judge has announced the closing of rebuttal, the accused shall have the right to make a final statement.

Article 163, Public Announcement of Judgments and Delivery of Judgments: Judgments shall in all cases be publicly announced.