INTRODUCTION

In the early modern period, being male or female was a fundamental legal status. In the legal apparatus of the time, a person’s sex had tremendous material and political implications for their rights and responsibilities. These implications extended throughout various fields of law: property ownership, inheritance, capacity to contract, marriage and domestic relations, legal procedure, criminal culpability, enfranchisement, and so on (Langley and Fox Reference Langley and Fox1994, 1–10; VanBurkleo Reference VanBurkleo2001, 9–16). As a result, legal authorities were at times called upon to determine an individual’s sex.

Determination of sex for individuals was not an issue that troubled legal authorities often. Nevertheless, in some cases, not terribly common but also not so rare, sex did not declare itself at birth but, rather, puzzled viewers such as family members, neighbors, employers, midwives, and doctors. People with unclear sex were legally referred to by the Latin term “hermaphrodite” (Dreger Reference Dreger1998, 31–32; Oxford English Dictionary Online, n.d.b).Footnote 1 Scholars working on the history of hermaphrodites often cite the classical legal formula, shared by several legal systems from at least the thirteenth century, that resolved sex ambiguity using a theory of dominancy—that is, asking which sex (male or female) is more prevalent in the individual.

This understanding of sex correlated with the Hippocratic/Galenic one-sex model, which conceptualized females as “underdeveloped males” who “lack vital heat” (Laqueur Reference Laqueur1992, 4; R. Gilbert Reference Gilbert2002, 36). Historian and sexologist Thomas Laqueur (Reference Laqueur1992, 135) noted that sex was a sort of “shaky foundation” that could change through time and place and that genitals were indicative but not determinative. Because sex was considered to be an unstable trait at the time, courts and magistrates tried “maintaining clear social boundaries, maintaining the categories of gender” (135; emphasis added). Doing so was crucial for social order. As historians of women and of intersex people recognized, the differentiation between males and females was essential and instrumental to maintaining the political distinctions between men and women. In fact, the growing separation between them in early modern English political life was accompanied by a surge in legal writing about hermaphrodites in the eighteenth century. In this article, I discuss a body of such early modern legal treatises on hermaphrodites—some examined for the first time—to suggest that legal writing about hermaphrodites in that century represented an impulse to clearly delineate the male-female boundary in multiple areas of law and was likely fueled by a desire to ingrain a separation between males and females in more legal spheres.

Although treatise writers offered an explication of the law on hermaphrodites, it was courts and justices that actually listened to testimonies, viewed evidence, and made factual determinations about an individual’s sex, and such judicial classifications are the focus of this article. Its main argument is that, in the early modern period, the common law practice was to defer to commonsense classifications of sex and not to medical classifications, as was customary at the time in continental Europe. Specifically, I show that in eighteenth-century England, courts that classified hermaphrodites did so by relying on lay witnesses and not on the testimonies of doctors or physicians, despite their increasing authority in scientific circles and popular venues outside the court in England. I attribute this difference to the relatively late bloom of medical jurisprudence in England compared to that in continental Europe. I further suggest that, from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, justices gradually began to believe that the commons were unfit to classify hermaphrodites, and, as a result, they aspired to facilitate an “enlightened” and professional legal process to prove sex. This aspiration, documented in the late eighteenth century, eventually led to the diminishment of lay knowledge in sex classification in common law and to a conceptual transformation in the legal meaning of sex—from a “shaky” continuum to a binary.

My analysis is based on close readings of new primary and secondary sources related to several trials involving hermaphrodites. Central to this analysis are six trial records related to four people who were suspected of being hermaphrodites in England and Colonial America between 1629 and 1787. Two of the trials—those of Constantia Boon and Betty John—are explored in this work for the first time, as far as I am aware. Thomas/ine Hall and Chevalier d’Eon have already been the subjects of much scholarly interest, but they have been explored outside the legal field.Footnote 2 D’Eon’s trials, in particular, have not been examined, to the best of my knowledge; Hall’s trial, in contrast, has been closely analyzed in works of historians of early America who stressed the crucial role of community members in sex determination in this time and place (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1978, 146–48; Brown Reference Brown1995, 171–93; M. Norton Reference Norton, Hoffman, Sobel and Teute1997; Reis Reference Reis2009). My analysis will build on these works from a legal perspective, and then it will shift to focusing on my own examination of other trials conducted in common law courts. My readings of these cases are supplemented with new primary sources, such as dictionaries and pamphlets published in that time frame (1629–1787). They are also supplemented by canonic histories of intersex people in North America and Europe by Elizabeth Reis, Alice Dreger, Greetje Mak, Lorraine Daston, Katharine Park, and Anne Fausto-Sterling, which have largely explored the medical and cultural history of hermaphrodites in early modern times and until today (Daston and Park Reference Daston and Katharine1998; Dreger Reference Dreger1998; Fausto-Sterling Reference Fausto-Sterling2000; Reis Reference Reis2009; Mak Reference Mak2013). By contributing a robust legal perspective to these works, this article helps identify and illustrate the special role that law and legal procedure played in major documented developments of the time, such as the rise of the concept of “true sex” and the rise of medical jurisdiction over hermaphroditic bodies in Europe and early America. Attending to the differences between legal systems in England and continental Europe also helps uncover the way in which early modern common law conceptualized sex at the time.

The particular history of sex classification in early modern common law is important for several reasons. First, it implies a strong relationship between the legal procedure of proving sex and the ontology of sex itself. Laqueur’s (Reference Laqueur1992, 8) important argument was that, in the early modern period, sex was a sociological, rather than an ontological, category. Accordingly, this article examines the relationship between the ontology of sex and the legal procedure of proof. It demonstrates how judges acted as epistemic gatekeepers to support the transformation of sex from one kind of category to another and shaped the meaning and content of sex by managing evidence and witnesses. Legal scholars such as Ariela J. Gross (Reference Gross2009) and Ian Haney-López (Reference Haney-López2006) have done similar work to explore how legal procedure in courts constructed whiteness or non-whiteness in cases of doubt, but no such work has been done regarding doubtful sex. Thus, joining existing scholarship on the legal construction of race, this article demonstrates the constitutive character of evidentiary legal procedure in creating categories of identity and personhood.

Second, the history of judicial classifications of doubtful sex in early modern common law offers insights into the conceptual sex/gender divide. The particular history of sex classification in common law provides relevant historical context for the ongoing debate about the meaning of sex in US jurisprudence and, specifically, for whether the term “sex” refers to reproductive organs or also includes cultural and social attributes, usually termed “gender.” This article demonstrates that the legal fact of sex in early modern common law was neither exclusively corporeal nor exclusively behavioral or social—it was a mixture of these attributes, molded into a judicial decision—and this practice was bound up with common law’s core philosophy of trusting common sense. The cases presented here thus provide a unique and revealing perspective on how sex and sex ambiguity were conceptualized, regulated, and controlled in a pre-scientific legal context before the modern conceptual separation between sex and gender took hold.

Third, the article stresses the particular role of law in facilitating the social acceptance of the Aristotelian model that denied the existence of hermaphrodites and stated that “men and women were unequivocally different categories” and the ideal of “true sex” (R. Gilbert Reference Gilbert2002, 36–40).Footnote 3 Although celebrated writers such as Laqueur (Reference Laqueur1992) and Michel Foucault (Reference Foucault1988) have historicized the dramatic transformation in the meaning of sex, their works encompass a range of cultural, religious, and medical—but not so legal—institutions. This article builds on their work by using historical legal treatises and trial cases to illustrate how the legal institution contributed to the process of constructing sex and gender in early modern times. I argue that justices wanted to detach themselves and the court from “fables” about hermaphrodites and that they aspired to facilitate a modest and professionalized judicial classification process. These changes not only impacted the lives of intersex people considerably but also had dramatic consequences for thinking about sex in the long run—mainly, the idea that sex classification is fundamentally a scientific endeavor and not a legal one.

HERMAPHRODITES AND LEGAL MONSTERS

“Hermaphrodite” is an ancient term, historically used to describe someone possessing both male and female anatomical characteristics from birth. Hermaphrodites were culturally and legally associated with the notion of “monsters,” which was a label used for babies born with abnormalities so severe as to undermine the baby’s status as a human being (Daston and Park Reference Daston and Katharine1998, 173; Reis Reference Reis2009, 23). According to Foucault (Reference Foucault1980), a monster in this sense is a “juridico-biological” problem. As an exceptional deviation from the general species, such a person disturbed the regular application of rights and duties and presented a “double breach”—that is, they violated both the laws of nature and the laws of men and combined the impossible with the forbidden (Daston and Park Reference Daston and Katharine1998; Sharpe Reference Sharpe2010). The hermaphrodite, then, was a particularly intriguing type of monster for jurists.

The legal category of monsters entered English law in the thirteenth century and was historically associated with the legal category of hermaphrodites as both appeared and disappeared from English law at approximately the same time (Sharpe Reference Sharpe2009).Footnote 4 English jurists described “monsters” as possessing severely deformed bodies or being in the shape of “beasts” (106). The essential purpose of this legal category was to discern who was a legal person and who was not. For example, according to the law, “monsters” could not inherit land. If there was no successor other than a legal monster, then the land was handed over to the lord (Blackstone Reference Blackstone1753, 247).The legal category thus identified those who fell outside the borders of humanity and of law.Footnote 5 English law’s definition of hermaphrodites appeared in proximity to the legal category of monsters in the thirteenth century. The English jurist and justice Henry de Bracton (Reference Bracton1968; n.d.), who wrote one of the most fundamental treatises of English law, On the Laws and Customs of England, introduced a definition of “hermaphrodite” right after the category of monsters. He cited Roman law authorities, saying: “Mankind may also be classified in another way: male, female, or hermaphrodite. Women differ from men in many respects, for their position is inferior to that of men” (Bracton Reference Bracton1968, 31) and that “[a] hermaphrodite is classed with male or female according to the predominance of the sexual organs” (Sharpe Reference Sharpe2009, 105).Footnote 6

Despite the cultural and legal proximity of hermaphrodites to monsters, however, hermaphrodites were never considered legal monsters. Instead, they maintained a separate human status—one between males and females (Sharpe Reference Sharpe2009, 101–2). Bracton’s definition of hermaphrodites was cited four centuries later by renowned English jurist and justice Sir Edward Coke (Reference Coke1979, 7.B), in his classic book Institutes of the Laws of England (1628). The book provided a comprehensive and updated description of common law, which referred to hermaphrodites as having indeterminant sex: “Every Heire is either a male or female. And an hermaphrodite, that is both male and female. And an hermaphrodite (which is also called Androgynus) shall be heire, either as male or female…. And accordingly it ought to be baptized…. An hermaphrodite may purchase according to that sexe which prevaileth” (3.A, 7.B).Footnote 7

Bracton’s and Coke’s earliest references to the category of hermaphrodites in English law are revealing for their mundane treatment of sex ambiguity. Despite the cultural association of hermaphrodites with monstrosity as a symbol of “divine wrath” (Daston and Park Reference Daston and Katharine1998, 176; Sharpe Reference Sharpe2009, 111), it seems that throughout the long, clearly multifaceted period stretching from the thirteenth century to the eighteenth century, hermaphrodites were associated with a benign meaning of monstrosity that also existed at that time—a sort of “ornament” of nature that evoked sensations of pleasure and curiosity (Daston and Park Reference Daston and Katharine1998, 177).Footnote 8 For example, Jacob Giles (Reference Giles1718, n.p.), a prolific English legal writer on common law who published in 1718 the Treatise of Hermaphrodites and described hermaphrodites as “wonderful” secrets of nature and “curious discoveries.” As this article will demonstrate, legal treatises and case law from early modern times consistently identified hermaphrodites as part of humankind and not as supernatural or subhuman monsters (Sharpe Reference Sharpe2009, 130).Footnote 9 They were human, and, therefore, they could inherit property and engage in other legal actions; however, they had to do so as either males or females.

A TOUCHSTONE FOR MALE-FEMALE POWER STRUGGLES

Alongside the cultural recognition of the fundamental humanity of hermaphrodites grew a practical legal approach regarding how they ought to be regulated in the civil sphere with respect to their sex. Bracton and Coke’s definitions of hermaphrodites, and their later instantiations, required that such people be treated according to the most dominant sex—either male or female. This dominancy model implied that the legal approach of common law conceived sex to be a relative position between two poles rather than a pure dichotomy. That is, the assignment of hermaphrodites to one of the two recognized sexes lacked the modern notion of “true sex” that supposedly lies within any individual and needs to be revealed and declared.Footnote 10 Rather, Bracton and Coke’s definitions described hermaphrodites as either possessing an intermediate position between male or female or as possessing elements of “both,” though they still expected hermaphrodites to be “sexed” to either male or female.Footnote 11 In Treatise of Hermaphrodites, Giles (Reference Giles1718, n.p.) also described hermaphrodites as “a mixture of both Sexes, and to both incompleat [sic].”

Despite such legal recognition of a state of sex indeterminacy, however, a condition of sexual ambiguity was not sustainable in the law. As Foucault (Reference Foucault1998) has pointed out, sex ambiguity disturbed the peaceful application of the law and the assignment of rights and duties to individuals. Because the common law system (like many others) differentiated between males and females in significant ways, various treatises and expositions of the law attempted to clarify and regulate hermaphrodites’ ability to engage in different sex-restricted legal actions. Against the ambiguity of sex in hermaphrodites, treatise writers reacted with solidifying male-female distinctions in the law. For example, the constitutive definition of hermaphrodites in English law was intrinsically affiliated with their capacity to be heirs. This is because in medieval England, women’s capacity to succeed was vastly restricted. Land was usually passed to the eldest son according to the practice of primogeniture. Some of these practices continued into the early modern period as well (Blackstone Reference Blackstone1753, 902). Carole Shammas (Reference Shammas1987, 150) notes that in the English inheritance system “one son usually inherited a disproportionately large share of an estate.” The classification of hermaphrodites as males or females could therefore have significant capital consequences, and legal treatises attempted to regulate those. English jurist John Godolphin (1701, 387) stated in Reference Godolphin1701 that if a mother gives birth to a hermaphrodite child, then the child is to accept a portion according to the sex most likely to be assumed. However, if “that is also doubtful, it is presumed according to the more worthy Sex, viz. Masculine.”

For the purpose of criminal appeals, because women were not able to appeal (except in the case of certain events, like the murder of a husband or ancestor),Footnote 12 legal writer and judge John Comyns (Reference Comyns1762) stated in his 1762 Digest of the Laws of England that “the heir who brings the Appeal must be a male. … Or, an Hermaphrodite, if the Male Sex be predominant; otherwise, not”Footnote 13 (W. J. 1710; Giles Reference Giles1719, 5; Macnair Reference Macnair2004). In the field of contracts, a person’s sex was also legally significant. The English legal writer William Sheppard (Reference Sheppard1656, 188) explains: “An Hermaphrodite may give or grant, take or purchase as another person may do; according to that sex which prevaileth.”Footnote 14 Here again, hermaphrodites were fit to engage in certain types of contractual actions, but their sex status carried significant financial consequences. For example, under the doctrine of coverture, a husband and wife were considered to be one person, which meant that a married woman’s legal being was subsumed by her husband’s and, therefore, her contractual engagements were void (Zaher Reference Zaher2002, 460–61).Footnote 15 If a hermaphrodite person was married, their classification to one sex or the other would thus determine the validity of the person’s contractual engagements.

The intensive legal attention given to the relatively uncommon subject of hermaphrodites by treatise writers in the eighteenth century alludes to the legal commitment to protecting male privileges as defined by the separate-spheres ideology of the time. According to Mary Beth Norton (Reference Norton2011, 4), it was during this time that Anglo-American society ascribed females with activities located in the household, whereas males were designated for positions in the political sphere of governance. Protecting and enhancing male privileges went hand in hand with ascribing these differences in the body. From this perspective, treatise writers can be seen as guarding legal privileges (such as engaging in contracts, inheriting land, or bringing a criminal appeal) against being used by non-males or by individuals whose maleness was in doubt. Not for the first time, the treatment of hermaphroditic bodies and discourse about them represents an impulse to clearly delineate a male-female boundary as a way to enforce the political status quo between them.

THE COMMONSENSICAL APPROACH TO SEX IN COMMON LAW

Legal recognition of sex ambiguity and the accompanying legal commitment to classifying hermaphrodites as male or female are not unique to common law. Roman law, for example, also interpreted sex as a matter of dominancy and as a relative status; these views served as a source of authority for Bracton’s (Reference Bracton1968) thirteenth-century definition of hermaphrodites (Nederman and True Reference Nederman and True1996, 511–15; Iacub Reference Iacub2009, 2763; Sharpe Reference Sharpe2009, 105–7).Footnote 16 Nevertheless, common law’s approach to hermaphrodites and to sex was unique in its method of proving sex. Whereas civil legal systems relied on specialized and medical opinions of sex in the process of legal sex classification, Anglo-American case law concerning intersex people related somewhat differently to medical authorities in such matters. That is, rather than relying on such expert opinions, common law valorized commonsense wisdom to determine sex. Daniel Boorstin (Reference Boorstin1996, 113) notes that common law was “nothing else but custom, arising from the universal agreement of the whole community.”Footnote 17 Thus, as the cases presented later in this section will show, physicians, surgeons, and natural philosophers in both England and in the English colonies in America were afforded no special privilege over the community in the legal classification of sex, despite their rising authority to examine hermaphrodites outside the courtroom.Footnote 18 Judicial classifications of doubtful sex cases simply rested on commonsensical understandings of sex.

As a result, common law’s method of deciding which sex a person should occupy for legal purposes was not particularly structured or formalized. According to the rule of dominancy, common law expected intersex people to be assigned to one sex or the other based on the predominance of parts, the evidence for which could be rather arbitrary, intuitive, and unconfined. One striking example of such evidence is found in Giles’s (Reference Giles1718, n.p.) Treatise of Hermaphrodites, where he advises classifiers to examine features that range from body hair to bravery and pleasantness: “A person that is bold and sprightly, having a strong voice, much hair on the body, particularly on the chin and privy parts … are certain demonstrations that the hermaphrodite has the privy parts of a man in a more predominant manner than those of the other sex.” Similarly, he writes that if a hermaphrodite “has good breasts, skin smooth and soft … if there be a sparkling and agreeableness in the eyes … and if the vagina is not too defective, such an hermaphrodite ought to pass for a woman” (n.p.). I argue that such lack of formal methodology in the prevailing sex model and accompanying legal treatises left much to the discretion of judges, who, according to the common law tradition, gave weight to community opinions and the knowledge of lay witnesses and juries.

A paradigmatic example of the centrality of such commonsense knowledge is the case of a servant named Thomas/ine Hall, who in 1627 arrived in Warrosquyoacke, a small English settlement in Colonial Virginia (Brown Reference Brown1995, 176). The townspeople there questioned Hall’s sex. In 1629, after investigating the matter and failing to reach a final classification, they brought Hall to the General Court at Jamestown to determine Hall’s sex and guilt in the charge of fornication. Found in a modern reprint of the minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia, the testimonies portrayed in the court transcript reveal the various examinations conducted by the townspeople before arriving to court.

Historians such as Kathleen Brown, Mary Beth Norton, Alden Vaughan, and Elizabeth Reis have analyzed these testimonies to determine how such a town resolved issues of sex/gender ambiguity, and they found that the town’s investigators used two methods to determine Hall’s sex: the first was to question Hall and the second was to examine Hall’s body. One witness, for example, Francis England said that he “felt” Hall and pulled out Hall’s “members”—likely their male genitals—which made him believe that Hall was a “perfect man” (McILwaine Reference McILwaine1924, 194; Oxford English Dictionary Online, n.d.c). The most thorough physical investigation was conducted by a group of married women who examined Hall’s naked body several times and concluded that Hall was a male. The chief questioning, however, was conducted by plantation commander Captain Bass, who asked Hall to self-identity as a man or woman. Hall replied that they were both and that they had not made use of the male parts, described as an inch-long piece of flesh (McILwaine Reference McILwaine1924, 195).

When the case finally arrived in court, the judge—Governor Pott, who was also trained as a medical doctor—relied on communal knowledge through witnesses’ testimonies and did not initiate his own physical investigation. The court listened to Hall, who provided their life narrative. Hall testified to be born in England and baptized as a girl named Thomasine. At the age of twelve, Hall was sent to an aunt in London and then lived there for 10 more years, until Hall’s brother was drafted into the army. Hall testified to cutting their own hair, assuming male attire, and joining the English armed forces as a male soldier serving in France. Upon returning to England, Hall again presented as a woman and did needlework up until 1627, at which point decided to embark on a journey to the English settlement of Virginia and work as a male servant (Brown Reference Brown1995, 180).

After listening to testimonies, Governor Pott did not reach a conclusive sex classification; rather, he mandated that Hall add feminine accessories to his male apparel, likely to publicly signal his hybridity (McILwaine Reference McILwaine1924, 195).Footnote 19 This punishment was a significant deviation from the common law rule, which basically forced a male or female classification on people with doubtful sex, and scholars interested in Hall’s case attempted to understand what drove this change. Kathleen Brown (Reference Brown1995, 188–90) has suggested that Hall’s punishment reflects the court’s interest in addressing the colony’s need for workers, which led it to avoid corporal punishment and ignore the charge of fornication. Mary Beth Norton (Reference Norton, Hoffman, Sobel and Teute1997, 60), however, suggests that the townspeople were already firmly convinced of their own varied views regarding Hall’s sex and that any declaration by the court that affirmed one or the other was impossible, considering what was already known through oral and physical investigations of Hall. The court accordingly solved the clash by creating a singular category of sex for Hall.

A third possible explanation could be that in colonial America principles and doctrines from English law were largely applied based on the memory of local justices. That is, judges enforced a combination of what they remembered from English law and local practices and legislation, both of which could differ significantly from the original rule (Nelson Reference Nelson2008, 1:40–41). Considering that the extensive legal writing about hermaphrodites in treatises began slightly later and was produced mainly during the eighteenth century, it could be that Pott simply was not aware of the rule that required classifying hermaphrodites according to their most “dominant” sex.

Hall’s case also illustrates how local authorities balanced corporal and behavioral evidence to determine sex. The townspeople who attempted to establish Hall’s sex status repeatedly looked at Hall’s body, felt it, and questioned Hall, but they could not agree upon any final classification. Brown (Reference Brown1995, 173) suggests that the instability of sex differences was partly due to lack of “a coherent biological foundation for sex.” Mary Beth Norton (Reference Norton, Hoffman, Sobel and Teute1997, 64), on the other hand, argues that, in the process of communal reasoning, the body, and, particularly, the ability to consummate a marriage, were more important than Hall’s feminine gender. I agree with Norton that the body, and sexual organs, in particular, were an important factor to calculate; however, I suggest that fact makers in courts presented a fluctuating balance between corporal and behavioral indications. More cases reveal that gender served a critical function, along with the courts’ wish to restore social order regarding sexual norms, as Norton also indicated.

This article’s main contribution is that it draws connections between the centrality of the body, the structure of the legal procedure of proof, and the distribution of epistemic authority within it. I argue that the reliance of eighteenth-century common law on the opinions of community members to classify hermaphrodites contributed to rich understandings of sex that were not reduced to pure anatomy. Because the community’s understanding of sex was prioritized over medical opinions about it, sex classifications leaned on lay interpretations of body anatomy and, not less important, on the social interactions with the individual and the degree to which their behavior aligned with gender norms and stereotypes of the time.Footnote 20 This understanding clarifies that when a court seeks to understand if sex is more about biology or about behavior, the answer lies partly in the structure of the legal procedure. Accordingly, this article contributes to the conversation about the relationship between sex and gender for the purpose of legal classification of sex, advancing the view that the hierarchy of prioritizing sex over gender derives from changes in the legal procedure of proof.

To make the argument that common law judges in eighteenth-century England relied on communal knowledge when making sex classifications, I will review the legal cases of three individuals with doubtful sex from that period. These cases demonstrate that witnesses and juries relied on a mixture of social and physical elements, such as body structure, strength, baptismal name, life chronology, general mannerisms, and sometimes even external interests (such as political or professional prestige) in determining an individual’s sex. The gradually increasing epistemic force of medical and scientific accounts of intersex people appear in the background of these court cases, but they do not take hold inside the courtroom—yet. By the late eighteenth century, however, judicial quandaries regarding who and what to trust when determining sex reveal a general perplexity, surrender to specialized evidence, and a growing enchantment with a supposedly doubt-free culture of proof, leading to the acceptance of the true-sex paradigm.

Constantia Boon (1719): The Wisdom of Lay Juries

By the early eighteenth century, English physicians, anatomists, and philosophers of nature were already showing interest in intersex people and were attempting to view them as part of nature and classify them as either males or females. However, as exhibited in Hall’s case and in the other cases that will be presented, medical experts were not yet treated as privileged witnesses inside the court when adjudicating people’s sex. Rather, at least through the end of the eighteenth century, courts appointed juries and invited lay witnesses in order to classify intersex people.

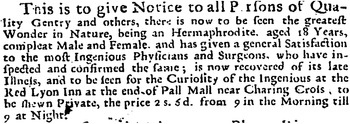

Such was the case of Constantia Boon, the famous hermaphrodite of Charing Cross. English physicians had become important validators and refuters of hermaphroditism in non-legal settings, and they published accounts and detailed descriptions of hermaphrodites who displayed themselves in public shows (Guerrini Reference Guerrini, Dyck and Stewart2016, 28). Advertisements inviting the public to view the spectacle prided themselves on receiving medical authentication: “There is now to be seen the greatest wonder in nature, being an hermaphrodite, aged 18 years, complete male and female. And has given a general satisfaction to the most ingenious physicians and surgeons, who have inspected and confirmed the same” (The Post Man, and the Historical Account 1714). The credentialed hermaphrodite publicized in this ad was Constantia Boon, who was presented to the English public in London and elsewhere around 1714 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Advertisement for the viewing of Constantia Boon in Post Man and the Historical Account, London, December 4, 1714. Credit: Public domain.

Physician and anatomist James Douglas, who believed that intersex people were actually “deformed” women, examined Boon in detail and delivered his account to the Royal Society of London in 1715 (Guerrini Reference Guerrini, Dyck and Stewart2016, 31).Footnote 21 Douglas reported that Boon was born in Deptford in 1697 and was trained to be a quilter by the name of Constant or Constantia. Her mistress observed something unusual and ordered Boon to be examined by an old woman, who immediately declared Boon to be a hermaphrodite. Boon’s mistress decided to present Boon as a “prodigy of nature” in Smithfield. According to Anita Guerrini (Reference Guerrini, Dyck and Stewart2016, 35), who examined the medical inspection of, and experimentation on, hermaphrodites in eighteenth-century England, Boon was a popular “high-end” exhibit—she demanded relatively high admission fees and traveled from venue to venue all the way to London. When Douglas examined Boon, he asked questions about her menstrual cycle and sexual preferences and then examined her genitals closely and invasively through vision, touch, and probing with instruments. Douglas detailed the shape and structure of Boon’s labia, clitoris, and vagina, contrasting them with the size and shape of a penis, scrotum, testicles, and urethra. Douglas concluded that Constantia was not a true hermaphrodite, as she did not have a double-sex set of functioning organs but was instead “a real woman with the addition of something extraordinary in her labia” (Guerrini Reference Guerrini, Dyck and Stewart2016, 42).

Douglas’s verdict that Boon—a validated, displayed hermaphrodite—was in fact or “really” a deformed woman and not a hermaphrodite was later repeated by other physicians with regard to other publicly displayed hermaphrodites.Footnote 22 According to Guerrini, public displays of hermaphrodites like Boon served as a space for the meeting of learned and popular curiosities. In these contexts, she says, physicians worked to create a hegemonic narrative of hermaphrodites by producing naturalistic descriptions, accompanied by illustrations and learned observations, that classified them to either sex (49). Despite these efforts, however, the capacity of such physicians to shape popular and even professional conceptions of hermaphrodites was limited, as the public and other professionals maintained the belief that true hermaphrodites can exist (50).

Four years after Douglas delivered his report to the Royal Society, a trial involving Boon offered new evidence that medical and scientific knowledge had not yet affected the adjudication of intersex people in court. Indeed, this trial serves as another case of judicial reliance on communal knowledge and its reliance on non-physical elements. Specifically, on September 3, 1719, the Old-Baily Court in London confronted the question of Boon’s sex when a woman named Katherine Jones was accused of bigamy. According to the court record, Jones married Boon in April 1719 at a private house in Blue Ball Alley, but she was already married to a man named John Rowland (Tyburn Chronicle 1768).Footnote 23 Remarkably, Jones tried dodging the accusation of bigamy by confessing to either marrying a “monster” or possibly a woman. That is, Jones acknowledged the two marriages, but she argued in her defense that Boon “was no Man, and therefore could not be a Husband; that it was a Monster, a Hermaphrodite, and had been shown as such at Southwark-Fair, Smithfield, and several other Places.”

To support her claim, some witnesses were called to court, one attesting that he knew Boon’s mother, “who brought it up as a Girl in Apparel and at School, and to handle the Needle, till it was 12 Years old, when he turn’d Man and went to sea.” Additionally, Boon appeared in court and testified to being a hermaphrodite convincingly: “She was also produc’d in Court, and own’d her being a Hermaphrodite, and having been shown; and it appearing by her own Confession as well as other Evidences that the Woman was more predominant in her than the Man.”Footnote 24 As a result of the evidence presented, the jury acquitted Jones of bigamy and released her from prison.Footnote 25

This decision—that Boon was more woman than man—was the easiest way to restore social order: in eighteenth-century England, both bigamy and sodomy were severe crimes that could be punished by hanging, but same-sex intimacy between women was not criminalized as was such intimacy between men (Binhammer Reference Binhammer2010, 2; Olsen Reference Olsen2017, 29–33). Additionally, juries in bigamy cases were reluctant to send bigamists to be hanged and tended to acquit defendants when some supporting evidence was presented (Capp Reference Capp2009, 553). These circumstances might explain why Jones preferred to admit that she had engaged in a void marriage with an individual who was possibly a woman—it would give the jury a way to avoid punishing her for bigamy. And if Boon wanted to protect Jones, presenting as a feminine hermaphrodite was likely the best strategy for doing so. Nevertheless, when Boon died in 1768 (Gentleman‘s Magazine 1768, 246), the case appeared in several reprints with an editor comment that affirmed the underlying fear of harming male privileges, such as marrying a different man’s wife: “We can only express our astonishment that an hermaphrodite should think of such a glaring absurdity as the taking of a wife!” (Tyburn Chronicle 1768, 329; Jackson Reference Jackson1794, 248).

Although no evidence regarding Boon’s anatomy was brought to court, hermaphroditic bodies in general were treated as a central site for community validation of sex, often in ways that undermined the individual’s wishes and autonomy. In the eighteenth-century world surrounding the Atlantic, the bodies of people of lower classes were often stripped and inspected. Unlike aristocrats who rarely exposed their skin, the bodies of the politically weak were more visible and scrutinized: the poor, runaway slaves, prisoners, army deserters, patients, or sex/gender transgressors were routinely inspected, described, and publicized (Morgan and Rushton Reference Morgan and Peter2005). Hermaphrodites’ sex was also a “subject for collective decision making,” and their bodies could be readily accessed by community members for observation and evaluation (M. Norton Reference Norton, Hoffman, Sobel and Teute1997, 55). Hall’s body was frequently examined by the townspeople, and Boon’s was examined first by her mistress and then by ticket buyers and physicians. There is no evidence that Boon agreed to participate in such exhibitions; according to Douglas’s report, Boon stated that she was sent to Smithfield fair by her mistress. Ruth Gilbert (Reference Gilbert2002, 136–38) argues that such public spectacles of hermaphrodites profited from the “colonial excitement” of seeing and knowing the body and further from the erotic nature attached to hermaphroditism. In these spectacles, scientists pried naked hermaphroditic bodies, determined to prove their sex, and made them into public scientific experiments (149). According to Guerrini (Reference Guerrini, Dyck and Stewart2016, 30), the “monstrous” or subhuman signification of hermaphrodites allowed physicians to subject their bodies to invasive and painful examinations and to produce detailed illustrations that were otherwise considered indecent at the time. As we will continue to see, people’s autonomy over their naked bodies was expropriated once their sex became a matter of doubt.

As mentioned earlier, this preference for having juries and lay witnesses, rather than medical professionals, decide hermaphrodites’ sex is unique to common law and contrasts with the then existing practices in civil law, which was practiced in other countries on the continent. For example, Daston and Park (Reference Daston and Katharine1985, 6; Reference Daston and Katharine1995, 425), historians of science who examined the history of hermaphrodite regulation, explain that in France, as early as the sixteenth century, medical commissions were appointed to help adjudicate defamation disputes in which one side called the other a hermaphrodite. They report that French magistrates referred alleged hermaphrodites to designated medical commissions consisting of surgeons, physicians, apothecaries, and midwives, and the magistrates deferred to these commissions’ judgments in every known case.Footnote 26 Scholarly literature indicates that such judicial reliance on medical classifications of hermaphrodites in continental countries persisted throughout the nineteenth century.Footnote 27 England, however, showed no such reliance on medical testimony in the case of hermaphrodites until late eighteenth century.

The difference between English and French courts can be explained by differences between the common law’s and continental law’s doctrines of evidence. The common law’s commonsense philosophy placed its faith in “the good sense of the laymen” so juries, rather than experts, were granted the authority to determine judicial facts (Boorstin Reference Boorstin1996, 111). Medical experts had been invited to testify in common law courts since the earliest days of common law, and, by the early modern period, such testimonies were in frequent use in England (Darr Reference Darr2014). However, during most of the eighteenth century, expert knowledge was not granted special status in the doctrine of evidence law. Indeed, before the modernization of evidence law doctrine, there was no meaningful difference drawn between the testimony of experts and that of lay witnesses in common law courts.Footnote 28 As Tal Golan (Reference Golan2004, 19) notes, experts ordinarily appeared either as regular witnesses or as specialized juries (the most well known of which was the all-female jury of matrons, usually summoned to make factual determinations in cases of sexual assault, pregnancy, and childbirth). It seems that, while the use of experts was becoming more prevalent in England in some contexts (such as homicide trials) during the eighteenth century, the question of hermaphrodites was still considered non-scientific and was therefore under the purview of regular juries, with the addition of the specialized authority of females over the sexed body during community investigations, as we saw in Hall’s case with the group of married women.

The nearly absolute dependence of common law on the knowledge of lay witnesses changed in the late eighteenth century, when Lord Mansfield’s decision in Folkes v. Chadd legitimized and endorsed the use of expert testimony to prove “matters of science.”Footnote 29 In the decades that followed, expert testimony was granted special status and privilege, and this status began receiving doctrinal recognition. The fourth edition of Geoffrey Gilbert’s (Reference Gilbert1795) The Law of Evidence from 1795 was the first evidence treatise to identify and define expert testimony as a special practice.Footnote 30 Following the habit of French lawyers, the treatise named this practice “proof by expert” and described its reliability. The authority of experts to provide opinions in their testimonies was further formalized in modern evidence law theory (Golan Reference Golan2004, 53). This change in the judicial status of experts and in the relevance and credibility of their opinions led to the growth of medico-legal studies, and fostered the development of English medico-legal forensic science, almost two centuries after this development in continental Europe.Footnote 31

According to Catherine Crawford (Reference Crawford, Crawford and Clark1994, 89), differences between the legal systems in England and those in continental countries were “crucial factor(s)” in explaining why medico-legal science lagged behind in England. First, unlike in England, continental systems provided medical experts with a formal status that made the practice of medico-legal investigations lucrative, exclusive, and desirable by physicians. English physicians, on the other hand, were reluctant to appear in court for lack of proper compensation and appreciation (91–94). Second, the law of proof developed differently. Moving from the Middle Ages’ proof by ordeal or battle, English common law used jury trial designated to reach “lay consensus” on disputed facts. In continental Europe, however, proof by ordeal or combat was replaced with judicial inquisition into the matter, without the involvement of juries (95–96). This difference led to the development of authoritative doctrine to help judges sort out evidence and testimonies in specific circumstances based in medical expertise and forming a massive body of medico-legal literature. The use of professional judges as fact triers in continental countries made it easier to integrate technical evidence in trials than in common law courts (97–101). Throughout most of the eighteenth century, English judges and juries did not use medico-legal investigations when determining the sex of hermaphrodites. Instead, judicial fact finders relied on their common sense and intuitions.

While both the juries, who relied on their commonsense judgment, and Douglas, who practiced a scientific examination, arrived at the same conclusion—that Boon was a woman, they did so on different grounds. Douglas viewed, touched, and probed Boon’s body, whereas the juries listened to testimonies and observed Boon and the other witnesses. Douglas compared her female genitals (labia, clitoris, and vagina) to the size and shape of male genitals (penis, scrotum, testicles, and urethra) and arrived at the conclusion that she was a “real woman,” whereas the jury was exposed to Boon’s life narrative, her upbringing, her education and training, and the fact that she switched to male presentation at the age of twelve and was presented as a hermaphrodite. It seems that because common law courts relied on evidence presented by lay witnesses, judicial classifications did not focus on bodily sex but, instead, relied heavily on the social or lived experience of sex. I argue that common law’s philosophy of valorizing commonsense knowledge and the use of the jury system to determine sex enabled rich concepts of sex to persist despite the rising authority of medical and scientific knowledge in extralegal fora.

More importantly, however, the juries and Douglas ruled based on opposing theories of sex. Whereas the juries classified Boon according to the common law framework established on the Hippocratic/Galenic dominancy model of sex and announced that Boon was “more female than male,” Douglas introduced a new concept of sex—the idea of “true” or “real” sex, which related to the Aristotelian concept of sex that placed males and females as opposites.Footnote 32 As we will see, the rising status of experts in common law had far-reaching effects on the identity of sex classifiers, the evidence that would be examined in court to determine sex, and the very concept of sex itself.

Cavalier d’Eon (1771–78): Erosion of Lay Knowledge

In addition to the reliance on lay witnesses, Hall’s case exhibited the informal authority of women acting as lay experts, an authority likely drawn from the all-female special jury. The jury of matrons was an English legal mechanism designed to provide the court with authoritative opinions on the female body in relevant legal contexts, such as rape, pregnancy, virginity, impotency, inheritance, and other instances that require examination of the female body (Oldham Reference Oldham2006, 80–104), especially from the sixteenth century until early in the eighteenth century (Forbes Reference Forbes1988, 22–33; S. Butler Reference Butler2019). Although Hall’s case demonstrates a cultural reliance on the judgment of such knowledgeable woman, the three trials concerning the sex of Cavalier d’Eon toward the end of the century—between 1771 and 1778—represent a diminishment in the cultural authority of female inspections and the classification of hermaphroditic bodies. They also show the judicial aspiration to separate the court from salacious collective investigations into a person’s sex and to situate the court as a virtuous and civilized forum.

Although d’Eon’s character and life have been a fruitful source of study for scholars in the fields of early modern history and the history of sex, gender, and sexuality, here we will analyze d’Eon’s trial records and examine them against the backdrop of scientific revolution and growing medical expertise. Doing so exemplifies a major shift in the judicial interrogation of sex that occurred at the turn of the eighteenth century—a shift in which learned minds moved from relying on common sense to relying on science in the classification of sex. The jury of matrons’ mechanism that was in use at the time occupied a middle ground between these two approaches. These matrons were supposed to examine the female body, but they may have been inspecting male bodies as well, as had been the case for centuries. In medieval England, for example, “wise women” assisted ecclesial courts in cases where a woman requested annulment of her marriage due to her husband’s impotency. According to Jacqueline Murray (Reference Murray1990, 240–42), these courts appointed a group of “honest women” to confirm such impotency, and, in such cases, the wise woman would not only examine and touch the husband’s genitals but would also sometimes attempt to arouse him sexually (242). Although it is not clear to what extent these kinds of ecclesiastical and canon law procedures for engaging matrons correlated with common law court procedures (Oldham Reference Oldham2006, 83), the common law court’s need to determine a person’s sex may have triggered its engagement of matrons to conduct similar inspections in an informal manner.

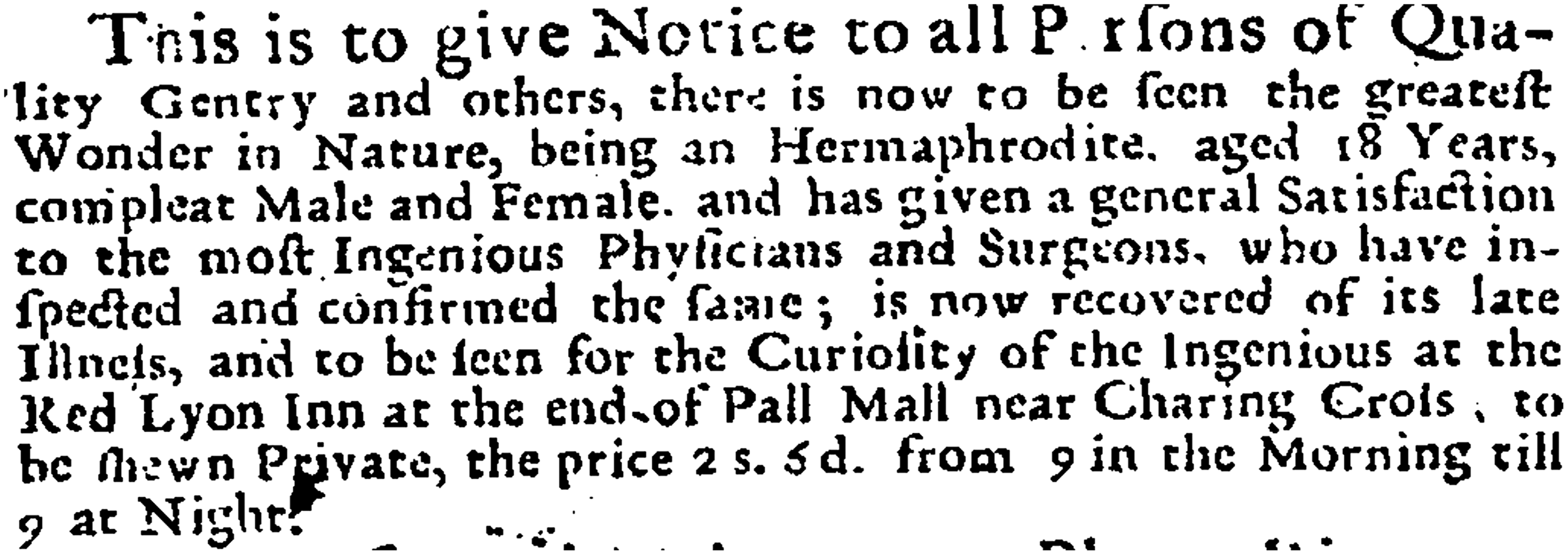

One humorous instance of such an inspection occurred as part of the incredible case of Chevalier d’Eon. Born in 1728 in a small town in Burgundy, d’Eon studied in Paris; he then became involved in French diplomacy and espionage in England, where he was part of a web of agents employed by the French Foreign Ministry called “The King’s Secret” (Conlin Reference Conlin2010, 46). D’Eon’s physique was known to be androgynous. Although it is not clear whether he had a habit of occasional cross-dressing in his youth,Footnote 33 rumors that d’Eon was a woman started circulating in London starting in the 1770s. He had already become a public figure by that time, so his sex became a popular topic for bets on London’s stock market (50). As with Hall and Boon before him, the question of d’Eon’s sex was a public one, well suited for conjecture and independent examination. Satiric documentation of what looks to be a mock trial to determine d’Eon’s sex was published in The Town and Country Magazine (1769), an eighteenth-century journal that shared the affairs of London’s upper class and “veiled ‘scandal’ tales, parodic ‘oddities,’ and satirical narratives” (Pitcher Reference Pitcher1983, 44). The featured trial was conducted by a jury of matrons, summoned to determine d’Eon’s sex conclusively: “The chevalier resolving to do himself justice, and prove his virility, had solicited several ladies of the first fashion, well known in the republic of gallantry, and completely qualified for the office, to form a jury of matrons” (Town and Country Magazine 1769, 249). The magazine published the alleged transcript of two sessions, with a parodic illustration and some ridicule of the matrons who attempted to determine d’Eon’s sex based on their past infidelities and experience with men (Burrows et al. Reference Burrows, Jonathan, Russell and Valerie2010, 117).

The publication of this mock trial was part of an established genre in eighteenth-century England: the publication of erotic trials. Emerging as a distinct branch of crime literature, newspapers and publishers printed detailed trials of divorce, adultery, impotency, and sexual perversions to attract buyers. These trials became “a popular form of soft-core pornography” (Kinservik Reference Kinservik2008, 10), and they were even more interesting when they involved high-ranking people and aristocrats. According to Peter Wagner (Reference Wagner and Boucé1982), medical reports in divorce trials had commercial value as they played “to the reader’s prurient interests” and were therefore placed in the title page. Sometimes they featured reports of matrons appointed by the court (Town and Country Magazine 1769, 225). The title page in d’Eon’s case promised “[a] humorous representation of a Jury of Matrons deliberating on the sex of the Chavalier D’E—n,” indicating both a cultural tradition of matrons determining sex and also an erosion in their status and that of their determinations in the late eighteenth century. The fact that d’Eon was a public figure made his mock trial suitable for publication. According to Wagner, pornographic trials were also an opportunity to embarrass French aristocrats. This mock trial implied that a known French spy and diplomat might be an impotent man or woman. Indeed, the accompanying illustration depicts d’Eon as proportionally smaller than the English matrons and as wearing a French symbol—the order of St. Louis necklace—around his neck (see Figure 2).Footnote 34

Figure 2. The trial of Chevalier d’Eon by a jury of matrons, in The Town and Country Magazine, vol. 3, 1771. Credit: Public domain, Google digitized; courtesy of HathiTrust, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hw28e0&view=1up&seq=276&q1=d%27Eon.

As in the later reprints of Boon’s case, the worry about blurring male-female boundaries was introduced here again, raising the specter of the formation of illegal marriages and the spread of adultery and divorce. The opening remarks by the chairwoman Lady Harrington stressed these fears, saying that this examination was important to the next generation because “if under the appearance of a male figure, any of our daughters should be so far imposed upon us to wed a woman, or even an hermaphrodite, what a disappointment must it not only be to them but our families, which may by that means become extinct!” (Town and Country Magazine 1769, 249). The report continued to describe the examination. Given the characterization of these trials as pornographic, it seems likely that the report of this one would include a thorough description of d’Eon’s private parts. However, although the illustration depicts a visual examination of d’Eon’s body using magnifying instruments (such as glasses and a telescope), the transcript mentions nothing of d’Eon’s body form or genitals. Instead, it reveals a parodic rationalization process; perhaps inspired by the historical contexts in which a wise woman aimed to arouse a husband’s suspected impotence (Murray Reference Murray1990, 246), d’Eon’s matrons based their judgments on their success (or lack of success) at seducing d’Eon: “I threw out every possible lure to induce him to make overtures to me, and almost solicited him to my bed, I never could get a tender thing from him” (Town and Country Magazine 1769, 249–50). On his writing skills, they declared: “I think he has so much sense to be a woman’s man; for all my lovers have been fools, and could never write a little better than myself.” The first meeting adjourned with the conclusion that d’Eon’s sex was “Doubtful” and scheduled to meet again soon “to determine finally whether the chevalier should remain of the Epicene gender”—that is, of indeterminant sex.Footnote 35

The second meeting opened with a resolution that d’Eon was female (Town and Country Magazine 1769, 305). D’Eon allegedly appealed the decision by arguing that such a conclusion would create great damage to the French court and nation (for having appointed a woman as a diplomat) and would jeopardize the peace treaty between England and France (306). The matrons’ further discussion revolved around their attitudes toward the peace treaty with France. At this point, d’Eon’s sex classification reflected their political preferences and personal beliefs. They did not change their ruling that d’Eon was a female and reported that d’Eon thanked them for “the impartial sentence, and just determination they had made in her favour.” Although the matrons had promised to remove doubt from d’Eon’s sex through an impartial sentence, the public was not convinced. Despite the publication of the matrons’ decision, d’Eon’s sex remained unresolved in the stock market, and bets regarding d’Eon’s sex generated legal disputes. The mock trial transcript ridiculed the jury of matrons and portrayed them as frivolous ladies with extensive sexual experience who used their sexual seduction capacity whimsically and not as a reasoned method for determining sex. Six years after the publication of his mock trial by the jury of matrons, d’Eon’s sex became the subject of lawsuits in a real court of law.

The cases, which were adjudicated by Chief Justice Lord Mansfield in the Court of King’s Bench in 1777 and 1778, stand in stark contrast to the depiction of d’Eon’s mock trial—they reveal how changing social norms of modesty and honorability shaped the process of fact making in the context of doubtful sex in common law. In the first case, Hayes v. Jacques, Mr. Hayes, a surgeon, paid Mr. Jacques, a broker, a sum of one hundred guineas in hopes of receiving seven hundred guineas if Hayes were able to evince that d’Eon was a woman (Ashton Reference Ashton1898, 159–61).Footnote 36 To offer proof, Hayes invited two witnesses who knew and had interacted with d’Eon. Both witnesses attested that d’Eon was a woman, based on their view of d’Eon’s body and the accompanying interaction on that occasion. The first, a surgeon named Mr. Goux, testified that “to his certain knowledge, the person called the Chevalier d’Eon was a woman” (159). In his cross-examination, he further explained that he examined d’Eon (at d’Eon’s request) regarding a disorder, which led to the discovery of d’Eon’s being a woman. The second witness, Mr. de Morande, testified that d’Eon had disclosed his female sex, wardrobe, and body to him on one occasion when d’Eon had invited de Morande to his house (160).Footnote 37 He further testified that, on one morning, the Chevalier had invited the witness to approach “her bed, and then permitted him to have manual proof of her being, in very truth, a woman” (160). As suggested earlier, both witnesses’ testimonies—including that of the surgeon—hinged not on abstract scientific theories regarding doubtful sex but, rather, on the direct observation of d’Eon’s body and interaction with him. A newspaper reporting on the case described the two witnesses as “physical gentlemen” to possibly signal their medical expertise (Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser 1777).

Despite this move toward a more scientific/medical form of reasoning, however, Lord Mansfield was appalled by the inquisition and “expressed his abhorrence of the whole transaction, and the more so, for their bringing it into a Court of Justice” and wished the dispute “might have better settled elsewhere” (Ashton Reference Ashton1898, 161). Nevertheless, Mansfield acknowledged that the law did not prohibit bets on this topic and advised the jury to find a verdict for the plaintiff Hayes, which it did, thus deciding winners and losers in all other outstanding bets on the topic (162).Footnote 38

A chance for Mansfield to repair the King’s Bench respectability arrived a year later, on January 31, 1778, when the question of d’Eon’s sex was raised again in Da Costa v. Jones.Footnote 39 In this case, the defendant’s counsel laid out two arguments appealing the jury’s earlier decision. The first was that the decision should not be enforced because it required the introduction of “indecent evidence” to the court and the second (suggested by Mansfield himself) was that “it materially affects the interests of a third person.”Footnote 40 Lord Mansfield accepted the latter argument, affirming d’Eon’s interest in the privacy of his sex. Mansfield also regretted that he had previously allowed confidential friends, acquaintances, and professionals to offer testimony on the issue and wished that they had refused to testify.Footnote 41 Although this may seem like a revolutionary ruling that signaled a humanization of hermaphrodites and viewed them as subjects of privacy, it was not so. Mansfield concluded that a person’s sex could be a legitimate subject for judicial interrogation depending on context and that, in contexts such as the case of a hermaphrodite heir, such an interrogation would be appropriate. In other instances, however, such as to rule on a bet, it would not be so.Footnote 42 In other words, he declared that judicial examination of a person’s sex would be perfectly fine when the hermaphrodite person was party to the legal dispute and the fact of their sex had legally enforceable consequences.

Reading Mansfield’s decision in d’Eon’s case against the backdrop of the mock trial by the jury of matrons reveals a tension between competing methods of proof, both contained within the common law tradition. Mansfield’s decisions in these cases seem to have been written to distance the King’s Bench from the indecency and primitiveness associated with the jury of matrons’ authority and the obscenity of pornographic trials. According to James Oldham (Reference Oldham2006, 113), the use of the jury of matrons apparatus had already decreased dramatically after 1720, partly due to growing medical and scientific authority of physicians. This change may explain why, by the end of the century (1771), the idea of sex determination by matrons had migrated to the realms of satire and ridicule and why Lord Mansfield wanted to distance the King’s Bench from this tradition. Nevertheless, the court still relied on community witnesses rather than medical experts. The doctrinal shift away from such witnesses and toward experts and science would follow Folkes v. Chadd some years later, and this shift would reduce common law’s traditional reliance on lay witnesses in such questions.

Hints to this shift appeared when d’Eon died in 1810, and a group of doctors, anatomists, surgeons, and other respectable men conducted a “complete inspection and dissection of the sexual parts” (Short Sketch 1810, 5). The report included a comprehensive description of his body, addressing in detail his face, body hair, arms, hands, fingers, and more, suggesting that they were feminine and “enabled him with more ease to carry on such a deception.” However, the group “decidedly ascertained, that the conformations of the organs was that of a male; and that all doubts, as to the identity of the person, might be removed,” likely due to their examination and dissection of his sexual parts, which are not detailed in the report. These findings made their way into later reprints of the Hayes v. Jacques case, which concluded with this statement: “When d’Eon died, in London, in 1810, it was proved, without a shadow of a doubt, that he was a man” (Ashton Reference Ashton1898, 162). As we will see in future cases as well, the transition from community and lay expert knowledge, such as that of the jury of matrons, to medical knowledge and expertise in d’Eon’s case indicates a desire for “doubt-free” proof and for evidence about sex that can be described as infallible.

In the era preceding scientific soundness, community investigations and their operation in court in the cases of Hall, Boon, and d’Eon demonstrate the way in which commonsense understandings animated the dominancy rule. The unstable and contingent nature of communal knowledge about sex meant that the legal fact of sex, which relied on that knowledge, could contain some doubt. That was acceptable in the legal system, where factual determinations were secondary to the primary objective of solving disputes; as a result, the fact of sex was determined instrumentally. Said another way, the dominancy of sex in legal settings was contextual and provisional and could potentially change. To be clear, medical knowledge of hermaphrodites at the time was also contingent and inconsistent; however, unlike judicial commonsense inquiry, the scientific inquiry sought to arrive at the correct answer and eliminate doubt as much as possible.

While the legal determination of sex remained instrumental throughout history, in the late eighteenth century, when sex became construed in the terms of a scientific fact, doubt was set to disappear from the legal fact of sex and from its legal determination. The idea of eliminating doubt using superior evidence interpreted by learned men was appealing to the common law judges. The next case demonstrates a part of this transition in which a late eighteenth-century judge surrendered easily to what he believed was superior knowledge and to a view of himself as an enlightened fact maker.

Betty John (1787): Judges as Enlightened Fact Makers

In addition to relying on communal testimonies, judges projected their own beliefs and understandings of sex into the courtroom. But in what way was judicial knowledge different from communal knowledge, if at all? This section will illustrate a judicial aspiration to facilitate a learned and “enlightened” procedure of proof to determine the sex of so-called hermaphrodites, as distinct from the procedures conducted elsewhere (for example, public fairs, the stock market, a mock trial). In d’Eon’s cases, for example, Lord Mansfield wanted to separate the court from popular investigations of sex. Over time, justices further diminished the authority of lay understandings of sex and acceded to medical proof. One way in which justices utilized their specialized status was through the administration of evidence. Sheila Jasanoff (Reference Jasanoff2018, 15–17) suggests understanding judges as “epistemological gatekeepers” who choose between types of authority without formal limitations. Given this understanding and the fact that modern evidence procedures were not formalized and were not consistently practiced in courts before the mid-eighteenth century, justices of the time enjoyed great procedural discretion when ruling on sex classifications.Footnote 43

When judges operate as epistemic gatekeepers, I argue, they are required to negotiate between their commitment to local common sense and their duty to function as skilled triers of fact. As Jasanoff (Reference Jasanoff2018, 17) argues, discretionary judicial acts are not mere subjective arbitrary actions but, rather, “amplifiers of common sense,” as they seek to follow a reasoning that is “rooted in engrained collective beliefs.” On the other hand, at least in theory, fact-finder justices operate under the mode of “trained observers” who possess the expertise to evaluate and administer evidence in an educated and accustomed manner (Riddell Reference Riddell1918, 1003). Their administration and evaluation of evidence within the sea of informality is designated to reflect a higher standard of judgment and reasoning—that which is held by a learned professional judge and not by “tailors and shoe-makers” (1004). For common law justices, epistemic gatekeeping is conducted within these conflicting commitments: to higher reason, on the one hand, and to common sense, on the other hand.

In the context of doubtful sex, the question of whether to turn to experts to determine sex very much hinged on whether justices viewed the matter as scientific and as a question of their understanding of sex. It seems that for most of the eighteenth century common law justices figured that sex determination was in the purview of common sense, but toward end of the century, they began to view sex determination as a scientific matter that required external expertise. The trial of Betty John shows the efforts made by an English court of requests to make factual determinations that speak to commonsense logic but, at the same time, to assume judicial expertise that echoes scientific ideas about hermaphrodites.Footnote 44 As described earlier, the surgeon James Douglas (who examined Boon in 1715) had already argued that true hermaphrodites do not exist and that those perceived to be hermaphrodites are actually “deformed women” (Guerrini Reference Guerrini, Dyck and Stewart2016, 31).Footnote 45 Some decades later, James Parsons (Reference Parsons1741), a physician who was admitted as a fellow of the Royal Society as well as a former student of Douglas, published A Mechanical and Critical Enquiry Into The Nature of Hermaphrodites. The text was written following the arrival in London of “[t]he Angolan,” a celebrated hermaphrodite who was exhibited in different theaters and cafes (Parsons Reference Parsons1741, 1751, 142). Parsons’s (Reference Parsons1741, vi–x) primary aim was to convince both popular opinion and learned individuals that hermaphrodites do not exist among humans and that believing that they do is a superstition or vulgar error that needs to be abandoned.

Such denial of the existence of hermaphrodites was intertwined with the gradual acceptance of the Aristotelian model of sex, which viewed males and females as opposite ends of a distinct binary and rejected the dominancy model embedded in the old law (da Costa Reference Da Costa2004, 137). Eighteenth-century English dictionaries already expressed this view in their definitions of “Hermaphrodite,”Footnote 46 and toward the mid-nineteenth century, admitting that hermaphroditism existed was seen as a token of ignorance and boorishness in medical circles (Dreger Reference Dreger1998, 139; Reis Reference Reis2009, 8).Footnote 47 The association of this belief with vulgar commonality also appears in the case of Betty John, held at the Birmingham Court of Requests in England. The report begins by describing a potential plaintiff who wished to sue a potential defendant for failing to pay a debt (without further details); however, the plaintiff was not sure of the defendant’s sex because the defendant had been known in public in both male and female presentations. Following unsuccessful inquiries into the matter, the plaintiff filled out the summons with two names—Elizabeth Alias and John Haywood—and added: “Let the sex be what it would” (Hutton Reference Hutton1787, 425). Although the plaintiff’s name and the exact date and year of the case are not mentioned in the report, it was published in a thick volume from 1787 and written by William Hutton, who served as a commissioner and president in Birmingham’s Court of Requests sometime after 1769 (Elrington Reference Elrington2004).

As will be made clear, Hutton’s (Reference Hutton1787, ix) report of the case is not a mere presentation of the facts and legal outcome, but it can also be read as a firsthand monologue that describes the dilemmas and contemplations of one judicial fact finder in a case of doubtful sex in late eighteenth-century England.Footnote 48 The report echoed the historical association of hermaphroditism with sub-humanity: “The animal appeared in court in a female habit, was rather elegant, of a moderate size, tolerably handsome, about thirty-two, had a firm countenance, and manly step, no beard, eyes susceptible of love, a voice tending to the masculine, with manners engaging, and was rather sensible” (426). The name attributed to her was Betty John, but Hutton did not seem convinced she was indeed a female: “As it attended the court in female dress, I shall take the liberty of treating it with a feminine epithet” (426). This representation of John by Hutton reflects the turning point described by Elizabeth Reis (Reference Reis2009, 22–23), who argued that starting in the late eighteenth century, the anxiety that dominated the interpretation of hermaphroditic bodies by doctors had changed. The old fear of godly wrath as manifested in monsters was gradually replaced by fears related to crossing racial and sexual boundaries. Accordingly, hermaphrodites were not perceived so much as monsters but more as deceivers or frauds.

As in the earlier cases, the question of John’s sex became crucial to the outcome of the legal proceeding—if she were a married female, as suggested by the presence of her alleged husband in the courtroom, the disputed debt might have been voided under the rule barring wives from forming contracts (Hutton Reference Hutton1787, 426).Footnote 49 Because her sex and marital status were fundamental to the result of the procedure, the court was presented with evidence regarding John’s sex and the validity of her marriage to the man.Footnote 50 In one version of the report, it is implied that a marriage certificate was “passed from hand to hand for inspection” but was not accepted, as it looked like it had been scribbled by a “school-boy.” This mention raises the possibility that a jury was appointed, but considering that this is a simple procedure in the court of requests, it is likely that the hands and eyes inspecting the note belonged to the people in the courtroom.Footnote 51

The report offered a candid consideration and evaluation of the evidence presented in this case, which demonstrates that Hutton was attempting to follow the ideal of a learned and civilized judge. Hutton (Reference Hutton1787, 426) mentions that “the common opinion of the ignorant, who knew her, was, that she was an hermaphrodite. Partaking of both sexes.” He further noted that the belief in the existence of hermaphrodites belonged to an era “marked with credulity” in which “every ear was open to wonder.” As noted, by the mid-eighteenth century, the notion that hermaphrodites did not exist and were most likely females or males had already started taking root in the learned texts of anatomists and surgeons. The idea that hermaphrodites did exist became associated with a lack of sufficient knowledge about the body and with an old, primitive world. As a result, Hutton evaluated evidence brought to him according to these higher standards of validation, and he concluded that John was actually a man in disguise—a husband and not a wife:

It appeared, from undoubted evidence, that, while she dressed like a man, she was suspected to be a woman; but in both dresses was strongly suspected to be a man … while the defendant carried a male dress, she spent her evenings at the public house with her male companions, and could, like them, swear with a tolerable grace, get drunk, smoke tobacco, kiss the girls, and now and then kick a bully. Though she pleaded being a wife, she had really been a husband, for she courted a young woman, married her, and they lived together in wedlock till the young woman died, which was some years after and without issue. She afterwards, like people of higher rank, kept a mistress, and ran away with her. Forcible evidences like these were sufficient to convince the wisest head upon this bench, or any other, that a man in disguise stood before them. (Hutton Reference Hutton1787, 426–27; emphasis added)

Following this presentation of “forcible evidence” pertaining to John’s romantic history and mastery of masculine behaviors, the court was persuaded that John was not a woman and not a wife but, rather, a man and, therefore, liable for the debt: “Her wife living peacefully with her all her days, without one complaint of the breach of the marriage covenant, evinced there was no defect…. Her being well versed in the art of kicking, further proved she was a man” (Hutton Reference Hutton1787, 428). John’s sexuality and ability to pass as a man were threatening to the status quo. Here, as in Boon’s case, a finding that John was a woman would have had atrocious implications for the separate spheres’ ideology—after all, if a woman could so successfully occupy a male-dominated sphere, what justified the separation in the first place? The socio-political separation between men and women was established based on clear and determinant differences between males and females. Accordingly, deciding that John was a woman would jeopardize the validity of this premise, so this conclusion was not one the judge was willing to draw easily.

However, a major turning point arose after John failed to pay her debt and was sent to prison. Then, Hutton (Reference Hutton1787, 429, emphasis added) reports: “It appeared from incontestable proof, that she was a real woman, and a real wife.” Hutton’s report implies that such evidence was probably gathered through physical examination upon John’s arrival to prison: “[S]he had nothing of the man about her higher than the feet.” According to the report, it was not possible to change the verdict in her favor at this point, and, eventually, John “cancelled the debt, by a confinement of forty days” (429). The fact that Hutton surrendered to supposedly physical evidence implies that he grew to believe that a superior means of proof was available outside of court and foreshadows what came next: judicial submission to professional classifiers who examine the body. His use of phrases such as “real women” and “real husband” as well as his decision to introduce the case under the heading “error in judgment” suggests that Hutton was impressively skeptical regarding his own capacity to make a “correct” classification (425).

Considering that Hutton identified John’s original classification as male almost completely based on behavioral factors such as her “masculine” traits and actions, while referring to her anatomy only implicitly by mentioning her satisfying marriage to a woman, as well as his later change of mind after discovering presumably physical evidence, also indicates the growing authority of the physical body over social indications for determining legal sex. The case of Betty John as reported by Hutton offers insight into one judge’s state of mind when administering evidence regarding a person’s sex. Hutton asked to distinguish judicial reasoning from the ignorant opinion found on the streets—that John was a hermaphrodite—and presented an evaluation of evidence that he believed would make sense to both the “wisest heads” and to “any other” person. Then, he was forced to confront the deficits in his own knowledge and reasoning. Although his approach to judicial sex is instrumental (that is, he treated the definition of sex as a necessary step to apply the law correctly and solve the dispute), he used new terminology with respect to sex. He used language that identified it as a condition that has true and false qualities and that can be evaluated and classified outside the court by using better evidence and methods than those available to judges.