Jean Hurault, abbot of the Benedictine Abbey of the Holy Trinity in Morigny, died in August 1560 with a troubled conscience. According to the abbey's seventeenth-century historian Basile Fleureau, Abbot Hurault was haunted by a ‘trial until the end of his days, which affected him greatly’, sent to ‘this good abbot’ by ‘God, who knows how to punish his servants by the fire of tribulation’.Footnote 1 The tribulation that Fleureau discussed in his history concerned the theft of ‘the holy relics, and of all of the silverware of the abbey, which happened in 1557’. The theft and burning of relics were a terrible sign of God's wrath. At a time when portents, preachers, and the religious pluralism that followed in the wake of the Reformation led people across France to believe that the end of the world was approaching, the theft at Morigny was as clear as if God had struck the abbey with lightning.Footnote 2 Yet Abbot Hurault may have died with a second tribulation on his conscience, one that might have made the providential significance of the nocturnal theft as clear as daylight to the people of Moringy. For years, Abbot Hurault tolerated a sodomy scandal that all of Morigny knew about but which only came before a criminal court after his death. This scandal was the case of Pierre Logerie, known as ‘the gendarme of Morigny’, one of the earliest and most detailed sodomy cases preserved in the criminal archives of the parlement of Paris, a court that tried hundreds of criminal cases on appeal every year from across its jurisdiction that covered over half of the French population, or around eight to ten million people in this period.Footnote 3 In October 1561, the magistrates of the parlement condemned Logerie to death for sodomy after he was accused of having sex with at least fourteen young men from Morigny. If the theft of the abbey's relics in 1557 caused Abbot Hurault's conscience to burn with ‘the fires of tribulation’, how intensely might it have raged with the knowledge that he had permitted the sin of sodomy to go unpunished in his abbey?

This article analyses the sodomy scandal of the gendarme of Morigny in order to tackle an apparently simple yet persistent question in the history of early modern criminal justice, and one that is particularly relevant for sexual crimes such as sodomy which courts claimed to treat with severity but in practice rarely prosecuted. Why, despite all of the formal and informal obstacles in their way, did plaintiffs bring charges before a criminal court in this period? Legal historians do not strictly recognize this question as a problem for consideration, since they are more interested in the jurisdiction of the courts and the formal terms by which they justify their decisions.Footnote 4 Yet recent research has posed a serious challenge to legal historians’ assumptions, drawing on the theoretical insights of anthropologists and the empirical findings of social and cultural historians. Researchers in these fields have demonstrated both how courts in this period lacked resources to pursue prosecutions effectively and also how people throughout the social hierarchy made use of a variety of alternative forums for dispute resolution beyond state institutions.Footnote 5 Making a formal allegation before a court proved to be an expensive and sometimes dangerous step for the victims of crime in the early modern period. Nevertheless, criminal courts at this time did prosecute large numbers of cases that have left significant traces in the archives, records that have enabled historians to explore tensions in daily life throughout the social hierarchy in ways that give voice to people whose experiences are often not accessible with other kinds of sources.Footnote 6 Understanding how best to interpret this rich surviving evidence therefore depends on a clear grasp of how people used the legal resources available to them in criminal courts as well as the alternative modes of conflict resolution that they might have pursued at the same time.Footnote 7

This problem of how far people were willing to make use of criminal justice in order to resolve their disputes takes on a new dimension in analysing sodomy cases. Even in the eighteenth century, when the available criminal archives are more abundant after the Paris lieutenance de police dedicated significant resources for investigating moral crimes, it often remains difficult to discover how sodomy cases came to a criminal court in the first instance.Footnote 8 Cultural and legal norms posed a potentially fatal threat that inhibited anyone from daring to make an accusation of sodomy, a term that in early modern French legal records most often referred to anal sex between men or to bestiality, but also an imprecise range of other sexual acts such as the anal rape of women or public masturbation.Footnote 9 Anyone deemed to be complicit in same-sex sexual relations risked being liable to the death penalty, according to the terms of biblical, Roman, and customary law that applied in France in the absence of any early modern royal laws regarding sodomy. Leviticus 20.13 declared that ‘If a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them.’Footnote 10 But how could magistrates prove the crime of sodomy when its legal definition was so imprecise, evidence was so hard to gather, and the immorality that the term denounced was so difficult to identify? The challenges involved in making allegations of sodomy meant that the magistrates of the parlement tried on appeal only 131 cases of sodomy involving males from 1540 to 1700, and of those only 45 were punished in the parlement by death, while the others were either dismissed or given lesser penalties since the case files lacked sufficient proof.Footnote 11 Although accusations of sodomy were notorious among the court elites of early modern France, these scandals remained the subject of gossip as the nobility managed to avoid formal accusations of sodomy before criminal justice.Footnote 12

Statistics of criminal justice can outline the broader patterns of the business of a court but they also conceal the complexity of individual cases and make it difficult to understand how a case came to court in the first instance. The available sources make it possible to analyse the evolving scandal of the gendarme of Morigny, both because the surviving documents include the testimony of a greater number of witnesses than any other sodomy case tried by the magistrates of the parlement, and also since the events concerned took place in a location that sixteenth-century elites and a seventeenth-century local historian deemed significant, the abbey of Morigny. Nevertheless, the records of criminal interrogations pose problems of interpretation that are just as complex as those presented by statistics of criminal justice. Magistrates framed their questions according to the evidence they sought to elicit from the witnesses and the accused, while the witnesses or accused during their interrogations sought to secure or evade a verdict that risked a penalty of death. The imprecise terms used to describe the ‘unmentionable’ crime labelled as ‘sodomy’ render the language of the interrogations recorded by the scribe in the parlement's criminal chamber even more resistant to clear interpretation. Indeed, the difficulty of putting into words the sodomy scandal at Morigny played a crucial role in the outcome of the trial and helped to determine not only Logerie's death sentence but also the manner in which the witnesses avoided being charged with the crime themselves.

This article first examines the extent to which the people of Morigny knew about the sodomy scandal before subsequent sections explore the social, institutional, and legal dynamics that prevented the case from coming to court until the community in Morigny had no other choice than to proceed through formal criminal justice. Finally, the article evaluates the dynamics of the trial in the parlement that ensured the scandal of the ‘gendarme of Moringy’ reached a conclusion. What could tip the balance in Morigny from enforcing silence over Logerie's actions to prosecuting his behaviour as a sexual crime, transforming something deemed unmentionable into the focus of the community's and the court's attention? Magistrates in Paris asked this question of almost every witness in Logerie's case, challenging the witnesses and the accused to put into words something that had for so long remained unmentionable: ‘How then did it become known? (Comment doncques cela a esté sceu?).’

I

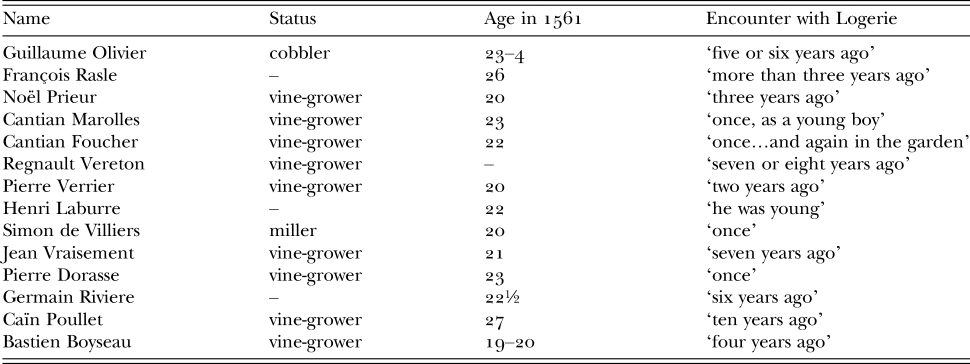

Pierre Logerie, known as ‘the gendarme of Morigny’, came, he said, from near Lusignan in Poitou.Footnote 13 He arrived at the Benedictine Abbey of the Holy Trinity in Morigny, founded in the eleventh century around ten leagues south of Paris, to ask ‘for alms according the ordonnance of the former king Henri’.Footnote 14 Logerie's nickname emphasized his strength as a ‘gendarme’ as well as his significant role in the abbey. Perhaps he would have made a good soldier in the Italian wars that had recently come to an end with the 1559 peace of Cateau-Cambrésis. He must have arrived in Morigny sometime between Henri II's accession in 1547 and the events described in his trial, that witnesses claimed took place as early as 1551 (according to Caïn Poullet) and as recently as 1560 (according to Bastien Boyseau). On Logerie's arrival, Abbot Hurault took him in and so bolstered his reputation for alms giving.Footnote 15 Guillaume Olivier said that Logerie was aged around sixty at the time the interrogations took place on 7 October 1561 and that he held the position as the porter in the abbey, in charge of everything from hiring gardeners to overseeing wine or book production. According to chapter sixty-five of the Benedictine Rule, the porter in the monastic community should be ‘a wise old man’, a layman who should have a room near the gate so that he could answer it ‘promptly, and with all the meekness inspired by the fear of God and with the warmth of charity’. He would also attend to ‘the water, mill, garden and various workshops within the enclosure’ and, the rule added, ‘should the porter need help, let him have one of the younger brethren’.Footnote 16 François Rasle added that Logerie acted as ‘the valet of monseigneur’, a title he would have most likely reserved for Abbot Hurault. Almost all of the young men interrogated along with Logerie worked in the vineyards and were in their early twenties by the time the interrogations took place in 1561 (see Table 1).Footnote 17 As the porter to the abbey of Morigny, Logerie acted as its gatekeeper and mediator with the outside world. But that world turned in on him when the criminal court of the prévôté in Morigny put Logerie on trial for sodomy and his case moved on automatic appeal to the parlement of Paris in March 1561.

Table 1 Witnesses interrogated in the criminal chamber of the parlement in the case of Pierre Logerie

The people of Morigny gossiped for many years that Logerie had committed sodomy without attempting to prosecute him before criminal justice.Footnote 18 Boyseau ‘said that the common rumour is that one named Bouveau served Logerie's needs and is known as his wife (la femme dud. Logerye)’. Regnault Vereton told the same story, stating that ‘the common rumour is that Bouveau acted as the woman with Logerie (faisoit la femme aud. Logerie)’, while Pierre Dorasse ‘said that the common rumour at Morigny was that Logerie is a bugger (bougre), and he was called this in the street, without him even taking issue with it’. Bouveau did not appear in Paris among the witnesses in Logerie's affair and was not named in any of the parlement's judgements. In early modern societies, common rumour proved a powerful way to punish someone informally by damaging their reputation in the community.Footnote 19 Rumour also gave an indication that someone might be suspected of a crime even if it did not count as a full proof in a court of law.Footnote 20 The claim that somebody accused of sodomy kept a ‘wife’ was sometimes made in jest during sodomy cases tried in Italy and Spain, although this is the only such instance in the sample of cases tried by the magistrates of the parlement.Footnote 21 Yet this allegation that Logerie was called a ‘bugger…in the street without him even taking issue with it’ was just as scandalous as him having a ‘wife’. Slander cases tried in early modern courts rarely arose because of insults about ‘buggery’ even if there is anecdotal evidence of their occurrence at this time.Footnote 22 As Dorasse said, Logerie ‘did not take any issue’ with the insult ‘bugger’, which might suggest he tolerated the insult and made no formal claim of slander against any of the people who had insulted him, however sharply the public denunciation might have stung. This was a common feature of criminal cases across early modern Europe, where years of gossip might precede a formal accusation.Footnote 23 Yet the build-up of common rumour against Logerie also seemed like compelling evidence in the court room. These claims stand out from the other allegations made by the witnesses in showing how the scandal of Logerie's behaviour was not just limited to the young men who testified against him and had spread across Morigny. Everybody knew, it seems, that Logerie was known as a ‘bugger’ because this is what the ‘common rumour’ told about him, and common rumour provided a significant indication of guilt.

Although the informal court of ‘common rumour’ had discussed Logerie's activities extensively, it took around a decade before the case was formally brought before criminal justice. When the vine-growers of Morigny were asked about this delay, they said that Logerie's overwhelming force compelled them to keep quiet about his actions. Poullet in his testimony claimed that Logerie put him under pressure not to denounce his unmentionable crime. When the magistrates of the parlement asked Poullet ‘if he spoke to his father about it’, he replied ‘no’. Then Poullet ‘confessed that, leaving his chamber, Logerie said to him that if he speaks about this then he would kill him. This frightened him, so that he dared not speak about this villainous affair.’ Doubting Poullet's testimony, the magistrates asked again ‘if he did not talk about this affair, how then did it come to be known?’ Poullet replied that, ‘when he left, Logerie was muttering. Logerie said to him that if he speaks about this then he would not stop pursuing him until he had killed him. And he said that he was forced, for fear of Logerie, to leave his village to go and live elsewhere.’ Most of the other young men reinforced Poullet's general claim that fear of Logerie kept them quiet. Germain Riviere said that he ‘dared not speak for fear of Logerie, and also because he had to make a living in the abbey’. Perhaps their claims seemed plausible to the parlement's magistrates, since fear of reprisals was a major reason preventing victims of crime from pursuing a formal prosecution throughout early modern Europe.Footnote 24 The interrogations reveal less about the fear that Logerie himself might have felt about the risk of prosecution, a fear that might explain his resort to violent intimidation of the witnesses.

The abbey of Morigny had close connections with the local institutions of criminal justice even if it failed to prosecute Logerie's case throughout the 1550s. Following the 1557 theft that stripped the abbey of its relics, Abbot Hurault took swift action to prosecute those responsible.Footnote 25 The morning after the theft, according to Basile Fleureau's seventeenth-century account, the monks entered the chapel to find the candle burning on the altar and the treasures of their abbatial church ransacked.Footnote 26 Their cries awoke Abbot Hurault, who was sleeping in his bed-chamber in the dormitory, and who soon publicly announced the theft in Morigny. The monks’ prayers were answered when, immediately after the morning mass, a letter arrived from a local nobleman Charles de Paviot, sieur de Boissy-le-Sec, that pointed the monks towards the thieves’ location. Paviot assembled the men of his village to join with the people of Morigny to seek out and arrest the thieves. They found them in Venant and managed to apprehend two of the group, although four or five other thieves escaped. Fleureau's source does not indicate which jurisdiction took on the case. Likely it was the same prévôté in Morigny that tried Logerie's case, although the records of the criminal courts in this region do not survive for the sixteenth century and so it is not possible to give a certain answer to this question.Footnote 27 Under torture, the leader of the group Joachim du Ruth, sieur de Venant, confessed and then was sentenced to death by breaking on the wheel for sacrilege. His son-in-law and his valet received the same punishment. Fleureau's account of the 1557 theft therefore demonstrates that the abbey was willing to denounce serious matters to criminal justice and to identify royal with divine justice.

Fleureau's account makes no mention of Logerie, who in his role as porter of the abbey surely bore some responsibility for the theft. As the gendarme of Morigny and gatekeeper of the abbey, Logerie should perhaps have intervened when he heard the disturbances in the abbey's church. Given Fleureau's silence on the matter, it is plausible to speculate that Logerie's failure to act might have increased the resentment of monks in the abbey against him, or even that the thieves might have known about Logerie and the sexual scandal at the abbey, and so they might have considered the abbey a soft target accordingly, one whose community would not dare to press charges for fear Logerie's scandal would come to light. The available sources do not permit a clear evaluation of these matters. Yet still after the theft of 1557 Logerie's scandal failed to come to court. It was only after Abbot Hurault's death that the criminal trial against Logerie could take place, which suggests that Abbot Hurault himself had a part in preventing the pursuit of the sodomy just as he encouraged and celebrated the successful prosecution of the theft in 1557.

II

The power of Abbot Hurault and his family in the abbey of Morigny, in Paris, and at the royal court had a crucial role in determining whether the scandal of the gendarme of Morigny would become a formal criminal case or remain the subject of malicious gossip. However, the magistrates later involved in prosecuting the case ensured that the name Hurault did not appear in any of the surviving case files and so maintained the family's reputation among office-holders in the capital. Abbot Hurault succeeded in preventing the affair of the gendarme of Morigny from becoming a scandal before a criminal court during his lifetime in a way that several other men of the church accused of sodomy in this period failed to replicate.Footnote 28

The Hurault family held powerful positions in the royal administration of early modern France that they passed on through the generations.Footnote 29 When Abbot Hurault died in August 1560, the monks buried him in the abbatial chapel in a tomb lying in the choir between the two pulpits, alongside his brother Nicolas Hurault, conseiller in the parlement of Paris.Footnote 30 The Hurault family not only lay their ancestors to rest in the abbatial chapel, they also purchased land around in this region, one favoured for investment by Parisian office-holding families whose rural properties enabled them to accrue seigneurial titles and use these lands to generate additional wealth by securing loan contracts against them known as rentes.Footnote 31 Since the prestigious abbey of Morigny proved integral to the Hurault family's authority, it is no wonder that Abbot Hurault's conscience burned so fiercely when crisis struck the abbey in the 1550s.

Abbot Hurault's death opened the way for a formal accusation to come from within the community at the abbey. When Abbot Hurault died in August 1560, it was his nephew who succeeded him, who was also named Jean Hurault, and who inherited from his father Nicolas the title of sieur de Boistaillé (this is how I will refer to him). Abbot Hurault's death meant that Logerie no longer had a patron in the abbey, no monseigneur for whom he could act as a valet. Moreover, the new Abbot Boistaillé did not reside in Morigny where Logerie might have appealed for him to continue his uncle's patronage. Like many previous abbots, and every abbot who succeeded him, Bostaillé held the abbey of Moringy in commendam, having been named by the king rather than being elected by the community of the religious order. This situation meant that Boistaillé was free to profit from the revenues of the institution without being resident, while the abbey's prior took charge of day-to-day affairs in Morigny.Footnote 32 By the time Boistaillé became the abbot of Morigny, he had held the office of conseiller clerc in the parlement of Paris from 1555 and served as a French envoy to Istanbul in 1559. While in post as abbot of Morigny, from 1561 to 1563, Boistaillé served as French ambassador to Venice, before returning to France and becoming a maître des requêtes in 1565.Footnote 33 Nowhere in Boistaillé's surviving diplomatic correspondence from Venice did he mention Morigny.Footnote 34 His embassy is best remembered for his critical, Gallican pronouncements on the Council of Trent and his activities as a book collector, begun in Istanbul, that led him to amass a vast library of printed books and manuscripts especially in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic.Footnote 35 If Boistaillé discussed France's troubles in his diplomatic letters, it was in general terms and not with any apparent concern for his landholdings or abbatial role in Morigny. Boistaillé described France's troubles as ‘a deplorable tragedy in this poor kingdom’ and, in the common eschatological language of his time, as ‘a spectacle of universal reckoning’. Yet he remained hopeful that ‘God would do us the grace of appeasing the factions of France’.Footnote 36 Boistaillé's conscience was troubled by international affairs when his predecessor Abbot Hurault agonized over the fate of his soul in Morigny. The new abbot's absence left the path clear for Logerie's enemies in the abbey to denounce him before criminal justice.

III

Bringing a criminal prosecution in the early modern period demanded an extraordinary mobilization of resources. To save the trouble, many cases were resolved outside of court even if office-holders in the courts insisted on their duty to prosecute crimes. The magistrates of the parlement of Paris chided Jean Gabriel, accused of ‘a great abomination’ and ‘the crime of sodomy’ in November 1609, when he tried to settle with his accusers before his case came to court, since the interrogating magistrate said that compounding a crime in this sense is ‘a way to ruin all the world’.Footnote 37 Bringing a case required arresting the suspect, gathering up the witnesses, persuading a court to take on the case, and pursuing the case through complex legal proceedings until the court reached a judgement. The more common means to launch a case was for a private person to act as a plaintiff by standing as a civil party (partie civile), funding the prosecution themselves and assembling the witnesses before the court.Footnote 38 Standing as a civil party could prove risky as costs might escalate but it also offered rewards in the form of a share of the fines or confiscations gathered after a condemnation. Yet this recourse to justice was not only the preserve of the elite. In the few sodomy cases where a definitive judgement by the magistrates of the parlement reveals the identity of the civil party, they are described as widows, merchants, a prior, a bourgeois of Lyon, and a nobleman.Footnote 39 Perhaps if an accuser was short of funds they might receive help from relatives, friends, neighbours, patrons, or clients. It was also possible to denounce a case to the court and ask for it to cover the fees, but only three of the definitive judgements in the sodomy cases tried in the parlement use the phrase ‘denunciation’, one by an apprentice, a second by two artisans, and a third by a nobleman and conseiller d’état.Footnote 40 In most cases tried in the parlement, it is not possible to trace the initial stages of the proceedings since the records of the subordinate courts rarely survive in this period.

According to an order of the parlement in March 1561, the case in Morigny began ‘on the complaint and denunciation of brother Olivier Doches, prior in the cloisters of the said abbey, along with the procureur of the lord abbot of Morigny’ and was taken up ‘jointly with the prévôt or his lieutenant in the prévôté of Morigny’.Footnote 41 The fact that the case proceeded before secular and not ecclesiastical justice suggests the public significance of the scandal involved which spread beyond the confines of the abbey.Footnote 42 None of the witnesses in Logerie's case named Prior Doches as the civil party and so it is difficult to assess his role in the developing scandal. Priors had a crucial role in Benedictine monasteries as second in command to the abbot, and so in Boistaillé's absence Doches would have governed the monastery. Chapter sixty-five of the Benedictine Rule warned that the appointment of a prior often ‘gives rise to grave scandals in monasteries’, especially if they ‘consider themselves second abbots’ and so ‘by usurping power they foster scandals and cause divisions in the community’.Footnote 43 In this case, the dispute arose between the prior and the porter who had been protected by the previous abbot. Nevertheless, the consequences of their dispute were serious for the community at Morigny. Logerie in his short interrogation in the criminal chamber of the parlement on 8 October 1561 focused his defence on ‘one of the monks’, who remained unnamed in the record. Logerie claimed that this monk sought to ‘chase Logerie out of the abbey…and that, in vengeance for the fact that Logerie wanted to control the books that he made in the abbey, the monk said that he would kill Logerie or it would cost him more than two hundred écus’. Since Prior Doches acted as plaintiff in Logerie's case, it is plausible to suggest that he was Logerie's unnamed enemy in the abbey. More significant is the fact that the magistrates in Paris did not pursue this line of enquiry and did not ask Logerie to provide evidence to justify his claims. The magistrates’ silence on Logerie's enemy in the monastery might suggest they did not take his defence seriously as a verifiable claim, or equally it might suggest they were unwilling to investigate the case any further and were content to accept Doches's account of events as plaintiff.

When Prior Doches finally instigated the case against Logerie, he and the rest of the monks at Morigny made use of a particularly effective means of gathering evidence. Several of the witnesses interrogated said that they only came forward because they heard a ‘summons’ and so felt compelled to depose against Logerie for fear of recrimination. From the evidence of these interrogations, François Rasle's testimony is significant since he reported that ‘it was the monks who brought him before the court’ and that ‘someone made him lift his hand, and that he never spoke of it again’. Guillaume Olivier confirmed this point when he claimed that ‘he did not tell anyone about it and said that he only spoke about it because of a summons (une monition)’, although he also contradicted this claim when he revealed that ‘he told some of the boys about it one day when they were playing bowls’. By invoking a ‘summons’, Rasle and Olivier were referring to the procedure known as the monitoire, which involved a call for information concerning a particular case that was read out on one or more Sundays during mass. Witnesses were asked to present themselves under threat of excommunication. By issuing a monitoire in Morigny, the abbey demonstrated how it had finally committed to put all of its resources behind the sodomy prosecution so that their ‘gendarme’ might at last be brought to justice.Footnote 44 The records of these interrogations following the summons would have formed part of the evidence in the case bags presented to the magistrates of the parlement as part of Logerie's appeal, evidence that the magistrates returned to the subordinate court once it had reached its final judgement.

Following years of neglect, when everyone seemed to know about Logerie's crimes but nobody attempted to prosecute him, Prior Doches instigated the case against Logerie by acting as plaintiff only once Logerie's former patron, Abbot Hurault, had died, and Logerie's enemies in the monastery apparently had gained control. The prévôté of Morigny heard Logerie's case and judged him worthy of the death penalty, when he would be made to feel the flames before being hanged, and then his body burned.Footnote 45 But this death sentence in Morigny was not put into action, or at least not yet. Logerie's case first appears in the archives of the parlement of Paris with an order of the court dated 24 March 1561, acknowledging that he had arrived in the prisons of the Conciergerie in Paris after appealing to the parlement against the prévôté of Morigny. Once Logerie had arrived in Paris, he was ready to have his case re-examined in the hope that the court would reduce his sentence.

IV

The manner of Logerie's appeal to Paris was typical but the way the magistrates of the parlement dealt with it upon his arrival was highly unusual. Having considered the case files brought from Morigny, which included the testimony of ‘the witnesses heard and examined in the said case’, the court ordered fourteen of those witnesses to be brought to Paris ‘the day after the feast of Quasimodo [the Sunday following Easter, or 13 April 1561] to respond to questioning on points resulting from the case, so that a judgement might be reached according to reason’.Footnote 46 The civil party would have paid their expenses at perhaps more than sixty livres in total.Footnote 47 The magistrates of the parlement rarely summoned witnesses in this way during the course of an appeal and even then such a large number is exceptional. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that Bouveau, the so-called ‘wife of Logerie’, was not among the witnesses who came to Paris (see Table 1). Perhaps Bouveau informally entered a plea bargain to give evidence in exchange for immunity from prosecution, or perhaps he simply fled.

When the interrogations took place in the parlement's criminal chamber on 7 October 1561, the magistrates struggled to cope with the exceptional number of witnesses involved in Logerie's case. The interrogations of the witnesses all took place on that day, but the scribe only recorded the interrogations of the first nine witnesses into the book of interrogations. The scribe then recorded the interrogations of the next five witnesses on a loose sheet also dated 7 October, conducted by the conseiller responsible for the case as its rapporteur, Estienne Charlet, and his colleague the conseiller, Jehan Barjot. Both of these conseillers were also present for the first phase of interrogations. This is an unusual record-keeping practice that perhaps became necessary only because of the large number of witnesses in Logerie's case. These pages show the criminal chamber struggling to cope with the number of witnesses involved, delegating the extra work to these junior conseillers to ensure that the business of the chamber could proceed without delay.

In their interrogations, the vine-growers involved in the sodomy scandal at Morigny argued that they did not come forward earlier because they feared they would be considered as Logerie's consenting sexual partners rather than the victims of his abuse. In this way, their testimony developed a compelling courtroom narrative that made a common charge against Logerie which invoked the gendered language of the biblical command ordering ‘If a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them’ (Leviticus 20.13).Footnote 48 Caïn Poullet used the same terms as seven other witnesses when he claimed that

About ten years ago he was working in the abbey and, one evening, when he was going to see his father, Logerie caught up with him on the path and took him away, leading him to his chamber where he took him to bed. Throughout the night, Logerie did not stop being up close to him and doing as a man does to a woman (comme un homme faict a une femme). The next day he [Poullet] went to his father's house.

Crucially, the witnesses alleged that Logerie acted as he might when he ‘lies with a woman’, directly evoking the biblical condemnation, while they insisted that they struggled against his violence. When Guillaume Olivier was asked ‘why did he suffer it?’, he replied ‘that he could not be the master over Logerie (qu'il n'en pouvoit estre maistre)’ and later ‘that as a young child he could not be the master over Logerie (ne pouvoit estre maistre dud. Logerye)’. The witnesses dared not risk allowing the magistrates in the parlement any suggestion that they were consenting, passive partners to Logerie's sexual advances. By making the claim that they were victims of Logerie's sexual violence, the witnesses’ courtroom narrative avoided the suggestion that they might themselves be considered complicit in the crime of sodomy.

The vine-growers reinforced their defence by insisting that they reacted with horror to Logerie's actions. The scribe recorded Poullet's testimony with the metaphorical language of the sin of sodomy by calling his relations with Logerie a ‘villainous affair (villain cas)’. Poullet insisted that Logerie was someone ‘who has done harm to his body’ and that a sense of guilt caused him physical harm when he ‘was ill for more than three days from displeasure at it’. The magistrates interrogating Poullet made use of this language of sin in their question by referring to sodomy as ‘such wickedness (une telle meschanseté)’. Boyseau similarly claimed that ‘he never spoke to anyone about it because the act is too filthy and shameful (trop villain et hort)’, while Dorasse condemned ‘the enormity and wickedness of what happened (l'enormitté et meschanseté du faict)’. The common moral language recorded by the court scribe in these interrogations suggests a degree of complicity among the parties in preparing their defence. Perhaps the court scribe also shaped their testimony to fit a common moral language regarding ‘sodomy’, yet minor variations between the witness testimony in answer to these questions and others suggests implicit collusion and a strong degree of pre-trial preparation rather than any direct scripting on the part of the magistrates and their scribes, who were charged to record the interrogations faithfully.

The vine-growers substantiated these discursive tropes of the ‘villainy’ and ‘wickedness’ of sodomy by emphasizing that Logerie had taken advantage of their youth, a plausible defence in patriarchal European societies when older men might claim sexual as well as social advantage over youths.Footnote 49 Olivier was not alone in insisting that ‘that as a young child (jeune enfant) he could not be the master over Logerie’. Noël Prieur ‘said that he was a young boy (jeune garson) and that Logerie led him into a bedchamber’ while Cantian Marolles ‘said that once, when he was a young boy (petit garson), Logerie led him into his chamber and that, when he was there, Logerie took him by force and made him lie on the bed. After supper Logerie closed the door.’ Their testimonies exploited the flexible definitions of childhood and youth made in different circumstances during this period.Footnote 50 Roman law fixed the age of majority at fourteen for boys and jurists used this definition when evaluating the validity of child testimony, yet the age of majority varied across France according to custom.Footnote 51 According to the customs of Étampes, which applied in Morigny, males could inherit movable property at the age of twenty and immovable property at the age of twenty-five.Footnote 52 If these allegations concerned actions that took place while Logerie was in his fifties, these vine-growers were aged in their teens and twenties when they encountered him, and so they were justified in identifying as ‘young boys’ (see Table 1). Yet the magistrates’ repeated questions about their relations with Logerie suggest that they prepared their line of questioning regardless of whether they were convinced by the vine-growers’ defence that Logerie had overpowered them. Since Roman and biblical law ordered that both partners in sodomy should be punished by death, the magistrates pursued this line of questioning in order to determine whether Logerie had abused the vine-growers by forcing them into sex against their will.

The magistrates of the parlement worked hard in their interrogations with the vine-growers of Morigny in order to determine the circumstances in which these witnesses engaged in a complex economy of intimacy that exchanged physical relations for social advantage.Footnote 53 Boyseau's interrogation indicates why these young men would seek out Logerie because ‘they thought they were with a respectable man (pensoit estre avecques un homme de bien)’, which suggests both masculine authority and social dignity, but also that they did not see him necessarily as effeminate or a risk to them.Footnote 54 As an apparently ‘respectable man’, Logerie could seem gentle with these young men and worked to win their trust. Simon de Villiers said

that one time Logerie asked him to go to bed with him but he did not want to go. In the end he did go. When he told Logerie that he wanted to sleep, Logerie said that he wanted to do things to him. While they were speaking Logerie became angry but then he calmed down.

Pierre Verrier's interrogation was reported by the scribe with a sensitivity to language that emphasized Logerie's art of seduction. First, according to Verrier, Logerie solicited him gently when he went and ‘fetched him (le vint querir)’ and then ‘asked him to share his bed (le pria de coucher avecques luy)’. In the terms of Verrier's testimony, only when he was in bed with Logerie did the latter show his ‘strength and power’ as Verrier claimed that Logerie's violent side finally emerged from behind his initially polite façade.

According to the Rule of St Benedict, as a porter Logerie acted as a broker for work in the abbey at Morigny, particularly in its gardens. In the interrogations, the abbey's gardens appear as Logerie's realm, where he expressed his masculine domination over the young men who worked there. Boyseau was sufficiently interested in going to bed with Logerie that ‘he asked leave from his master when Logerie told him to, because they were friends together (amys ensemble)’. Dorasse confessed openly that he had his father's permission to go to bed with Logerie.

He said that Logerie visited him only once. That day, at the grape-press, Logerie asked Dorasse's father if he would give him leave to go to bed with him, and the father agreed. After he woke up, having gone to bed with Logerie, Logerie spoke to Dorasse and took him by force. Then Logerie put himself on Dorasse as a man does to his wife.

Perhaps Dorasse's father hoped that Logerie's favour could help guarantee his son work in the abbey. This was a time when the clergy denounced same-sex bed-sharing as inappropriate and shameful, but it was the very ubiquity of bed-sharing that so frustrated them, an intimate practice that had a broader significance which signalled strong friendship or family bonds, and one that was often necessary in the close conditions of early modern life throughout the social hierarchy.Footnote 55 These testimonies reveal further aspects not only of Logerie's sexual abuse but also, finally, how the vine-growers of Morigny lived and worked with him for so long. Logerie offered these vine-growers work in the abbey but this came at the price of unwarranted attention. Nevertheless, in the first instance, these young men claimed they did not read any signs that suggested this attention would lead to sodomy. Only once the testimonies were gathered, the vine-growers claimed, did they realize the full enormity of the crimes of the gendarme of Morigny.

After the interrogations were concluded, the magistrates in the criminal chamber reconvened on 10 October in order to vote on the final judgement. The magistrates of the parlement confirmed Logerie's death sentence and ensured that ‘he shall be hanged and strangled and afterwards his dead body thrown onto the fire’.Footnote 56 The magistrates also ordered Logerie's possessions to be confiscated and awarded them to the abbey. Once this final judgement was confirmed, Logerie was sent back to Morigny for the death sentence to be executed, with the abbot Boistaillé already far away in Venice. Yet if the abbey, the returning witnesses, and the scaffold crowd could feel that they had brought an end to the scandal of the gendarme of Morigny, the developing religious conflict of these years gave little respite. The abbey at Morigny suffered further losses during the civil wars that immediately followed the sodomy scandal, as Protestant troops under the command of Gabriel de Lorges, comte de Montgomery, occupied the abbey in 1567 and threatened to destroy it, only for its nave to collapse a decade later under the rule of the abbot Jean Hurault III, Boistaillé's nephew and son of Robert Hurault, sieur de Belesbat, and Madeleine de L'Hospital, daughter of the chancellor, who apparently convinced the Protestants to spare the abbey because of suspicions that she shared their faith.Footnote 57 Who would the people of Morigny blame for their misfortune? Was Logerie the cause of God's righteous anger, or the Hurault family who profited from the lands yet showed so much negligence in managing the abbey's buildings and community? These are questions that cannot be answered with the available evidence, even if the sources themselves – the interrogations in the criminal chamber and Fleureau's ecclesiastical history of the abbey alike – suggest them through their apportioning of praise and blame.

V

Why did this case come to court when so many other crimes went unpunished in this period? The question at the centre of this article draws on both modern legal anthropology and the language of sixteenth-century inquisitorial justice as it was deployed in the case proceedings. Answering this question has wider implications both for the study of the role of criminal justice in early modern society as well as for how historians can engage with the ambiguous language of early modern inquisitorial records.

Considering the role of criminal justice in French society on the eve of the Wars of Religion, this article has argued that the social and institutional dynamics in Morigny were responsible both for preventing Logerie's case from coming to court in the first instance and also for encouraging the abbey to launch formal proceedings in court after years of determined neglect. While Abbot Hurault was overjoyed to prosecute the thieves who had ransacked the abbatial chapel in 1557, he seems to have made no effort to prosecute the sodomy scandal of the gendarme of Morigny before he died in 1560. No attempts to settle the scandal informally with Logerie during the 1550s appear in the interrogations. And the people of Morigny seem to have shown no inclination to prosecute Logerie before criminal justice even if they insulted him in the street. In this sense, the people of Morigny might be said to have tolerated Logerie's sodomy in the decade before the trial took place. Yet Abbot Hurault's death ultimately shifted the balance of power in Morigny so that the costs of launching a criminal prosecution for everyone involved were outweighed by the risk of ignoring the emerging scandal. Overall, this case demonstrates that criminal justice in the old regime could prove useful to plaintiffs in resolving their disputes, even in crimes as scandalous and difficult to articulate as sodomy, but only when the interests of local communities strongly aligned with those of the criminal courts where they sought justice.

Nevertheless, the precise manner in which the people of Morigny tolerated Logerie's behaviour with the vine-growers before the criminal case began is impossible to answer with certainty because of the ambiguous language of the surviving interrogations. This point reinforces the importance of reading criminal archives critically and with sensitivity to the interests and language of all parties concerned. The vine-growers made a coherent, compelling, and possibly contrived defence in order to prevent the magistrates accusing them of being complicit in sodomy themselves. The vine-growers argued that they had not denounced Logerie earlier because he had threatened them with violence and scared them into submitting to him, thereby avoiding the implication that they were guilty of sodomy by willingly lying ‘with a male as he lies with a woman’. However, some of the vine-growers revealed flaws in this argument. Caïn Poullet admitted that Logerie had asked his father for permission to sleep with him. Guillaume Olivier mentioned that the young men had spoken together about Logerie's actions when playing bowls. And still more people in Morigny than those who testified in Paris knew enough about Logerie's behaviour in order to insult him in the street. The magistrates’ questions that focused on the origins and development of the scandal itself – ‘how did it become known?’ – suggest a sceptical view of the vine-growers’ attempts to impose a normative interpretation of Logerie's sexual deviance characterized in their terms by ‘villainy’, ‘wickedness’, and ‘abuse’, since this question reminded the vine-growers that, however much they protested against Logerie's actions, they had neglected to denounce him before criminal justice. Yet the magistrates failed to generate sufficient evidence that would allow them to convict the vine-growers and so ultimately the court allowed them to leave without punishment.

Another ambiguity in the language of the parlement's record of the interrogations directly relates to the wider social and institutional dynamics of the case. Throughout the proceedings in the parlement, the magistrates deflected attention away from Abbot Hurault and his family as well as Prior Doches. Instead, they focused their questions on the vine-growers and their close relations with Logerie, who brokered their employment as the abbey's porter. These elite magistrates understood all too well the importance of friendship and power in achieving social advantage, as they navigated a world in which the sale of offices bound elite families’ wealth together with the prosperity of the state, relying on patrons, brokers, and clients in order to secure marriages and all manner of exchanges that guaranteed the transmission of offices within and between families.Footnote 58 None of the magistrates involved seemed to have wished for the reputation of the Hurault family to suffer because of the sodomy scandal in his family's abbey of Morigny. Ultimately, by neglecting the role of Abbot Hurault in Logerie's case, the court's final judgement perhaps extinguished ‘the fire of tribulation’ that the later Hurault and their relatives might have inherited – along with land, offices, and political influence – from that good abbot Jean Hurault. Logerie alone was punished in 1561 for the sodomy scandal in the abbey of Morigny, while its proprietorial family emerged unscathed. Once the magistrates of the parlement had reached their verdict, the vine-growers were free to travel home from Paris and continue to work in the fields around the abbey of Morigny, unaware that yet more tribulations were about to follow in the civil wars that struck so soon after their return.