Applying the principles of social inclusion to adults with mental health problems is increasingly seen as desirable. In the UK, the National Social Inclusion Programme has been established to take forward the recommendations of the Social Exclusion Unit's influential report and action plan Social Exclusion and Mental Health (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2004a , b ).

Much has been written about the history of the concept of social exclusion (Reference Percy-Smith and Percy-SmithPercy-Smith, 2000). It became influential in social policy at national and international levels during the 1990s (Reference Dahrendorf, Frank and HaymanDahrendorf et al, 1995; Reference Rodgers, Gore and FigueiredoRodgers et al, 1995; Reference RoomRoom, 1995). The European Union set up an observatory on national policies to combat social exclusion in 1991, and continues to reinforce the theme by requiring national governments to submit annual reports on how they are tackling the issue. This is one factor that keeps the theme live in UK policy circles and it tends to be adopted by interest groups whenever an injustice is perceived or policy priority is sought. In the media, ‘social exclusion’ seems to have passed into everyday use:

‘Of all the disadvantaged groups in society, the disabled are the most socially excluded. Until relatively recently, many were hidden away from the rest of society in institutions. But the problems that Britain's estimated 8.5m disabled people face have not gone away – life opportunities remain severely restricted for many’ (The Guardian Society, 1999, 28 July, p. 7);

‘The railways must combat the “social exclusion” that leads to professional people using trains three to four times more than non-professionals, the Rail Passenger Council said yesterday. It also called for increased, focused investment for rural railways’ (The Independent, 2000, 19 June, p. 8);

‘Ways need to be found to help pupils with emotional and behavioural difficulties in Northern Ireland to avoid them being socially excluded, it was claimed today’ (Belfast Telegraph Newspapers, 2003, 16 September).

Used as a term of condemnation, ‘social exclusion’ makes the accuser's position clear, but it begs the question ‘Who is excluding whom from what?’ In the examples given above, society appears to be excluding disabled people in general, the railways to be excluding non-professional people from using trains, and schools to be excluding certain children from their peers by suspending them from school. Beneath these answers lies a further layer of assumptions: that social exclusion can be remedied; that it should be addressed as a matter of public concern; and that responsibility for doing so is located in some agency. From the examples given, these may be large and indeterminate (society), private enterprises (the railways) or public bodies (education). Government is invoked to ensure that its own departments and other agencies take seriously their alleged responsibility for preventing social exclusion, and psychiatry has also been called to order with regard to the matter.

In the UK today, there is a strong consensus that the state has a role in reducing social exclusion; this follows directly from much European economic and social policy and it is also the understanding of the United Nations. But these supra-national bodies are predominantly concerned with gross forms of exclusion such as mass unemployment, slavery, disenfranchisement and oppression on ethnic grounds. Subtler forms of exclusion are at work in relation to the situation of people with mental health problems. It may help to understand the significance of social inclusion and its relevance to mental healthcare if we first undertake some conceptual analysis.

Defining social exclusion

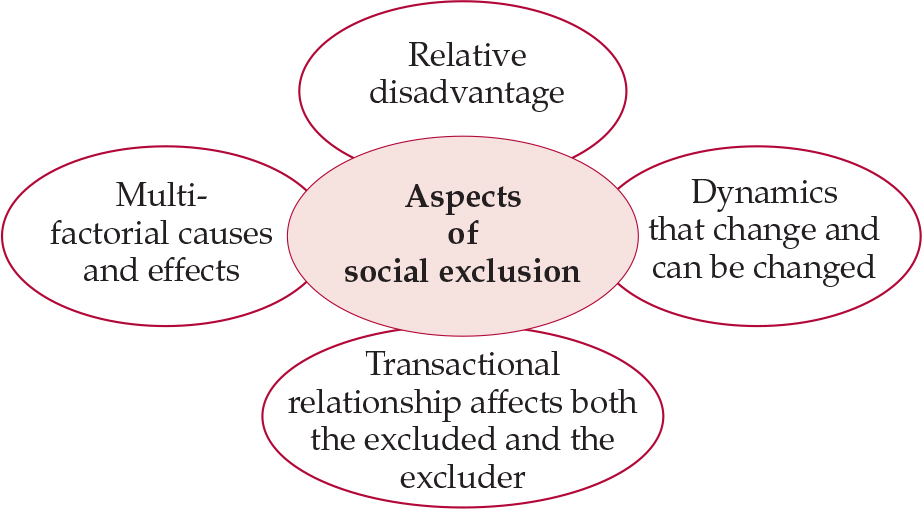

Exclusion is a complex concept and many uses of the term fail to do justice to its connotations. Social exclusion tends to be used to describe the position of an individual or group in relation to others, or in relation to benefits that society is supposed to offer, for example physical security, adequate nutrition, shelter, family life, employment, social support, community participation and political involvement. Often, for ‘social exclusion’ we can substitute the words ‘disadvantage’, ‘poverty’ or ‘discrimination’ without any loss of meaning. Yet it is overly simplistic to condemn everything one dislikes as ‘exclusion’ and everything one aspires to as ‘inclusion’. The analysis presented below identifies four key dimensions of social exclusion: the relative, the multifactorial, the dynamic and the transactional (Fig. 1). Each of these implies certain remedies for exclusion or approaches to inclusion, and thereby offers indications for mental healthcare and other agencies tasked with addressing social exclusion.

Fig. 1 Four key dimensions of social exclusion.

The relative dimension

First, the concept of inequality underlies most definitions of social exclusion, making it essentially a relative concept, akin to notions of deprivation or disadvantage. This is the most common understanding of social exclusion, and is reflected in the accusations against schools and rail companies cited above.

The multifactorial dimension

Second, social exclusion is inherently multifactorial: in addition to describing the position of an individual or a group in relation to other people or groups, the concept implies that this disadvantage is due to more than one factor (Reference Burchardt, Le Grand, Piachaud, Hills, Le Grand and PiachaudBurchardt et al, 2002). These factors may be interrelated, such as poverty, poor housing, poor education and poor health. Such an amalgam of problems has also been described as ‘multiple deprivation’. This is why the use of the term social exclusion in relation to rail passengers gives pause for thought. One might think that people who cannot afford to take the train are not disadvantaged in any other way, but describing their situation as social exclusion draws attention to the possibility that without this mode of transport they are also at risk of missing out on other entitlements, perhaps education or employment.

The dynamic dimension

Third, beliefs regarding multiple deprivation are far from new, but the concept of social exclusion adds another dimension, emphasising the processes that operate to create and sustain it. Exclusion is not a fixed state, it may be transient, recurrent or a more long-term experience (Reference Burgess, Propper, Hills, Le Grand and PiachaudBurgess & Propper, 2002). Hence, social exclusion is essentially dynamic: people move in and out of the conditions that lead to exclusion, for example poverty, unemployment or ill health. Reference GiddensGiddens (1998) stated that exclusion is concerned with mechanisms that work to disconnect groups of people from social mainstreams. This is sometimes referred to as a cycle of disadvantage or deprivation. The patterns and processes by which these movements into and out of social exclusion come about are therefore of interest to those concerned with social change, in particular if the mechanisms seem to be amenable to intervention. Reflecting this dynamic dimension, in 2004 the Social Exclusion Unit (now the Social Exclusion Task Force) published a series of reports entitled ‘Breaking the Cycle’ (http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/social_exclusion_task_force/publications.aspx#published97).

The transactional dimension

Finally, and most distinctively, social exclusion locates individuals or groups in relation to wider structures of society, so it has a transactional dimension. From this perspective, exclusion limits the interactions that are possible between individuals, families, communities, regions and even nations. Since these interactions are reciprocal, not only the excluded are affected: exclusion affects all of society, for better or worse.

Prison is an example of social exclusion that is planned and implemented by a system established to protect society and punish deviants. Slavery is an extreme form of social exclusion that both dehumanises individuals and deprives society of their full participation. Each describes a dyadic relationship (criminal justice system–prisoner, owner–slave) that is understood to have goals beyond the immediate interests of the parties directly involved. These higher goals are formulated in abstract terms: ‘law and order’ or ‘economic prosperity’.

This transactional aspect of social exclusion indicates that remedies cannot be found solely from the perspective of the excluded. Exclusion cannot exist unless someone or something brings it about, be it through inadvertence, the operation of a system (e.g. institutional racism) or active discrimination by individuals. A transactional understanding of social exclusion is of particular importance in the promotion of political engagement and avoidance of conflict.

The higher goal of ‘social cohesion’ has been introduced as the justification for actions to reduce social exclusion. In the face of the rapid changes brought about through economic integration and migration across the continent of Europe, social cohesion has emerged as a major policy objective in the UK as in other European nations (Reference LevitasLevitas, 2005): social exclusion poses a threat of social disintegration and, with it, economic failure.

What do we mean by socially excluded?

In short, when we say that individuals are socially excluded, we mean that they are disadvantaged and that this affects several aspects of their lives. Disadvantage is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of social exclusion. We also mean that they were not born disadvantaged and need not remain that way. Finally, exclusion is a two-way street: it affects people's status as members of a community and their political influence as members of a state; consequently, the wider society is also affected to the extent that it creates or tolerates social exclusion.

Social exclusion and the state

As outlined above, to proceed from the identification of social exclusion as an ill to the adoption of a remedy, one moves through an understanding, explicit or implicit, of how the state and society interact. It may be helpful to consider these responses in relation to alternative ‘discourses’ of social exclusion. Reference LevitasLevitas (1998) describes a discourse as a set of interrelated concepts acting as a ‘matrix’ through which to understand the world. Noting that the term discourse has to some extent replaced ‘ideology’ within social science, she points out that use of the word draws attention to the importance of language ‘not simply as a way of expressing the substance of political positions and policies, but as that substance’ (1998: p. 3). In relation to social exclusion, Levitas identifies three discourses (Box 1, items 1–3).

Box 1 Discourses of social exclusion

-

1 The redistributionist discourse: exclusion results from poverty and can be prevented by redistribution of wealth

-

2 The moral underclass discourse: individuals are responsible for their own exclusion, through their behaviour or cultural choices

-

3 The social integrationist discourse: ‘exclusion’ = ‘unemployment’, so paid employment eliminates exclusion

-

4 The societal oppression discourse: exclusion is the fault of the excluders, not the excluded

(Items 1–3 after Reference LevitasLevitas, 1998)

The redistributionist discourse

The redistributionist discourse is mainly about poverty: it sees income inequality as the cause of exclusion, and economic mechanisms such as taxation and welfare benefits as means to reduce it. The redistributionist discourse on social exclusion does not account for non-material causes of exclusion such as discrimination experienced by minority ethnic groups or disabled people.

The moral underclass discourse

The moral underclass discourse is concerned with the behaviour or the culture of individuals, for example young people, ex-offenders, single mothers or adults lacking basic skills, whose apparent failures and inadequacies are seen as the cause of their own exclusion. Remedies might include programmes targeted at specific social groups, for instance work-related training and parenting classes. With its focus on individuals and families, this discourse gives little attention to the structural or institutional factors that contribute to exclusion, such as inadequate housing, lack of amenities and labour market forces.

The social integrationist discourse

The social integrationist discourse sees inclusion mainly in terms of paid employment, to the extent that ‘inclusion’ and ‘employment’ are virtually synonymous. This is the understanding of social exclusion that dominates European social policy. It is also the nearest discourse to contemporary policy on social inclusion in England, illustrated by the emphasis on economic integration in the work of the Social Exclusion Task Force (2007):

‘Britain has enjoyed a strong economy and growing prosperity in recent years, but we would be more prosperous still if the talents of each and every member of the community could flourish. Social exclusion and wasted human potential are harmful to the country as well as to those individuals suffering from them’.

For the most part, the social integrationist perspective fails to address exclusion in the work place and gives little importance to unpaid work within society, which includes voluntary work, caring for dependants, neighbourhood and political involvement, and other activities associated with the strengthening of communities and the welfare of individuals.

A fourth discourse: societal oppression

These three discourses identify respectively poverty, culture and unemployment as the prime causes of social exclusion. We would like to put forward for consideration a fourth perspective, the societal oppression discourse (for its origins see, e.g., Reference Adams, Dominelli and PayneAdams et al, 2002). Societal oppression is mediated through interpersonal relationships, inter-group dynamics or institutional systems, and it appears to operate independently of the other three discourses. Social inclusion requires the more powerful actors to recognise the part that they play in oppressing the excluded. To some extent, this discourse is the inverse of the moral underclass discourse. In both perspectives, sectors of society are identified in terms of their personal attributes and are disadvantaged as a consequence. In the moral underclass discourse this unfavourable treatment is judged to be the fault of the victim, but in the societal oppression discourse, it is blamed on an unjust, powerful overclass. Like the other three discourses, the societal oppression discourse can be used to enhance our understanding of how to promote social inclusion. It may, for example, be applicable to the coercive role that psychiatrists have as agents of the state when implementing parts of the Mental Health Act.

A meta-discourse

The richness and utility of the concept of social exclusion is that it can be used to condemn a wide range of social ills and to justify any policy response that promises to remedy them. Groups whose political beliefs or discourses do not coincide can all decry it with a single voice, although they will differ over what to do about it. We may therefore call social exclusion and inclusion a meta-discourse; with these terms people from different political perspectives find a common language of condemnation and praise.

Social exclusion and mental health

‘Social exclusion’ began to appear in the mental health literature around the turn of the century (Reference SayceSayce, 1998; Reference Sayce2001; Reference MorrisMorris, 2001). The Social Exclusion Unit's report on mental health and social exclusion (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2004a ) showed just how far people with mental health problems fit the definition of the ‘socially excluded’. Responses are identified in the UK National Action Plan on Social Inclusion 2003–2005, which states that:

‘The fight against poverty is central to the UK Government's entire social and economic programme. Tackling the roots of social exclusion – in particular, discrimination, inequality and lack of opportunity – is an essential part of the vision of a successful and prosperous society. And breaking down barriers to employment goes hand in hand with promoting social inclusion’ (Department of Work and Pensions, 2003: p. 3).

The report was followed by an action plan on mental health and social exclusion (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2004b ), which evolved into the National Social Inclusion Programme, about which more is said below.

From exclusion to inclusion

Relativity

Prescriptions for alleviating social exclusion in mental healthcare may be derived from each of the dimensions and discourses identified here. For example, one remedy implied by the relativity of social exclusion is to reduce the differences between people with mental health problems and others. One major difference lies in the purchasing power of each group, with a high proportion of people with mental health problems reliant on social security benefits for their income. In this respect, the promotion of ‘direct payments’ is a step towards greater social inclusion (Box 2). Holding the budget for their own care has potential to place individuals with mental health problems on a par with people who have the financial resources to buy what they need. In practice, the opportunity is rarely realised, owing to low take up of direct payments (Reference Ridley and JonesRidley & Jones, 2002; Reference Newbiggin and LoweNewbiggin & Lowe, 2005). Nevertheless, financial strategies like these fit well within the redistributionist discourse, and their shortcomings reflect its blind spots: inequality is inevitably part of exclusion, but exclusion has other, additional causes. In terms of our dimensions, it is compounded from multiple sources. For a person seeking direct payments, poor education, low levels of social support or living in an area where there is a poor supply of care alternatives pose additional obstacles to social inclusion.

Box 2 Direct payments

‘The Community Care (Direct Payments) Act, introduced in 1996, gave local authorities the power to offer people a cash payment instead of direct services … The payments can be used to pay an agency to provide the support the individual wants, as well as to directly employ personal assistants to enable the person to live the way they want’

(Reference Ridley and JonesRidley & Jones, 2002: pp. 643–644)

Multiple deprivation

Responses to multiple disadvantages need to be multifaceted. In mental healthcare, this implies a need for concerted action from a range of public sector agencies, including health, social care, education and housing. An example in mental health is the development of care planning to incorporate assessment of diverse needs, mainly through the care programme approach (CPA). Not only is this more inclusive, it may also be more effective (Reference Schneider, Carpenter and WooffSchneider et al, 2002; Reference Carpenter, Schneider and McNivenCarpenter et al, 2004).

The discourse surrounding oppression is particularly relevant to the analysis of the multiple sources of exclusion. There is an imbalance of power between service providers and service users or carers. Knowledge about mental illness and decision-making power are unequally held. Paradoxically, therefore, being the focus of attention of mental health services can contribute to exclusion. Reference Noble and DouglasNoble & Douglas (2004) reported that service users want more involvement in decision-making about their own care, whereas carers want good information and communication with services. Services that work to increase participation and user (or carer) autonomy are essential components of a strategy to reduce social exclusion.

Dynamic theories about the origins and outcomes of mental health problems are familiar: one such is the vulnerability–stress–coping (or restitution) model of mental illness. Moreover, given the cyclical nature of some mental health problems and the therapeutic orientation of services, a dynamic understanding of social exclusion translates easily to mental health. From a dynamic perspective, the process whereby a person becomes socially excluded can be intercepted and countered. The discourses indicate possible tactics for doing so, but we have also seen that each discourse may be criticised for not considering some aspect of social inclusion. In particular, an intervention that helps one aspect of inclusion may harm another. Direct payments may reduce the relative disadvantage but might also entrench the individuals' dependence on benefits, preventing increasing social inclusion when their illness improves or remits. A dimensional approach to social exclusion helps us to examine the unintended effects of strategies to promote inclusion.

Social transactions

The relational nature of mental healthcare offers numerous opportunities for social inclusion to be increased or decreased. One burgeoning field of research and development concerns stigma, a barrier to social inclusion that operates at the level of public attitudes and can affect the self-confidence of people with mental health problems (Reference Rusch, Angermeyer and CorriganRusch et al, 2005; Reference ThornicroftThornicroft, 2006).

Demos and ethnos

Reference Huxley and ThornicroftHuxley & Thornicroft (2003) differentiate between two types of social inclusion: that which corresponds to the Greek idea of demos – the political community – which grants (or withholds) rights; and that which corresponds to ethnos – the cultural community – which relates to belonging. A person's membership of the demos means that he or she has the legal status of citizen and may participate in political life, but this does not necessarily involve acceptance as a member of the cultural community (the ethnos). The involuntary nature of some mental healthcare means that people may be detained against their wishes. The nature of this interaction is inherently exclusionary for the individuals affected, as it separates them from their usual social environment and also deprives them of fundamental rights. In doing so, it contravenes both ethnos and demos.

Implications for psychiatrists

To return to the questions implied at the outset, can social exclusion be remedied, should it be addressed and, if so, what responsibility does the psychiatrist have in this? The development of the National Social Inclusion Programme to oversee the implementation of the Social Exclusion Unit's report Mental Health and Social Exclusion (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2004a ) demonstrates the government's response in England to the moral question: it should be addressed. This programme is designed to coordinate government departments and is divided into seven areas, listed in Box 3. Therefore, the responsibility for fostering social inclusion is seen to lie with government departments.

Box 3 The seven areas addressed in the National Social Inclusion Programme

-

• Employment

-

• Income and benefits

-

• Education

-

• Housing

-

• Social networks

-

• Community participation

-

• Direct payments

Psychiatrists are clearly expected to play their part: in April 2007 social inclusion was named as a policy priority for mental health services over the next few years (Reference ApplebyAppleby 2007a ). Step-by-step guides to socially inclusive mental health services are available (Department of Health, 2006a , b ). However, the emphasis placed on breaking down traditional barriers could pose a threat to psychiatrists' professional identities: ‘Employment, housing and a strong social network are as important to a person's mental health as the treatment they receive’ (Reference ApplebyAppleby, 2007b : p. 1). A socially inclusive approach may also demand skills, such as community development and conflict resolution, that are not normally acquired though psychiatric training. This is reflected in their inclusion in the list of ‘essential shared capabilities’ for the mental healthcare workforce (Reference HopeHope, 2004).

There remains the question of whether social exclusion can be remedied. The National Social Inclusion Programme's Inclusion Database (www.socialinclusion.org.uk/good_practice/?subid=78) contains information on over 500 projects that ‘enable people with mental health issues to engage with their local communities’. It is organised into nine ‘life domains’ (Box 4). The database gives examples of what is being done in the name of social inclusion in mental health, but the rationale behind these activities is not explained and, as we have already been pointed out, there is danger in using the term ‘social inclusion’ simplistically to convey general approval.

Box 4 The life domains of the Social Inclusion Database

-

• Employment and training for work

-

• Education

-

• Housing

-

• Arts and cultural activities

-

• Physical exercise and sports activities

-

• Volunteering

-

• Faith-based groups

-

• Finance

-

• Neighbourhoods

Reference Repper and PerkinsRepper & Perkins (2003) provide a descriptive account of strategies to promote social inclusion from a mental healthcare perspective, with plenty of advice underpinned by practical experience. They report evidence that social inclusion can in certain circumstances be promoted by mental health services. However, if sustainable and replicable strategies for social inclusion are to be put in place, a clearer understanding of effective mechanisms to bring it about is required. In the next section we highlight theoretical frameworks from social psychology that might explain why certain types of organisational structure and interpersonal activity may be more conducive to social inclusion than others. Such frameworks enable the formulation of strategies to promote inclusion or diminish exclusion.

Social psychology

Social identity theory

Social identity theory is an attempt to understand inter-group discrimination. Its authors, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and WorchelTajfel & Turner (1979), posit that membership of social groups forms part of a person's self-concept and predict that people are positively biased towards their own group (the ‘in’ group). The theory brings together two fundamental cognitive concepts: mechanisms of classification, by which people, events and objects are placed into categories; and mechanisms of comparison, by which people compare their group with other groups. The product of the classification and comparison processes is ‘social identification’, which has an impact on a person's self-esteem. If membership of a group has a positive effect on self-esteem, then the individual's social identification with that group (the ‘in’ group) increases, leading the person to incorporate the group membership as part of their self-image. At the same time, a negative bias is predicted towards other groups (the ‘out’ groups). This bias can result in discrimination, leading to low self-esteem among ‘out’-group members and a negative self-image (self-stigma). This theoretical framework of social identity has been expanded in relation to people with mental health problems to explain stigma and to indicate how the impact of discrimination may be countered (e.g. Reference Link and PhelanLink & Phelan, 2001; Reference Corrigan and MatthewsCorrigan & Matthews, 2003).

Allport's contact hypothesis

Reference AllportAllport (1954) offers an alternative theoretical framework that might guide interventions to promote social inclusion in mental health. His theory, which has been developed mainly in relation to race and ethnicity, is known as Allport's contact hypothesis. Identifying ‘in’ and ‘out’ groups, the theory states that equalising the status between the two groups, for example through the pursuit of a common goal, will promote direct contact and that the familiarity that ensues offers an opportunity to disconfirm stereotypes. This in turn increases perceived similarity between the two groups and promotes greater liking. It is principally the positive contact (prolonged, meaningful, pleasant interaction) that has the desired effect, and this is generalisable to many types of group (Reference Pettigrew and TroppPettigrew & Tropp, 2006).

Conclusions

There is strong commitment to social inclusion in UK mental health policy and, more broadly, in European social policy. Social inclusion is a worthy goal of mental health services, but its attainment requires extensive social change. Within services, structures, systems and the balance of power between clinician and patient will have to be re-examined. Beyond services, social exclusion is perpetuated by public prejudice, by far-reaching discrimination and by the association between mental illness and other indicators of deprivation. The dimensions and discourses described here indicate many areas for intervention and various approaches that could be adopted.

Social psychology offers theoretical frameworks that may be used to identify promising interventions and predict their effects on social inclusion, but a more developed account of the mechanisms and causes of social inclusion in mental healthcare is needed. Social inclusion in mental health may be described as ‘a discourse in search of a theory’. A coherent theory of social inclusion in mental health could act as a fulcrum, turning policy commitment into systemic change. Without such a theory, the title of this article must remain a question.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

-

1 Social exclusion is a complex concept that is:

-

a correctly used only in government policy

-

b always misused by the popular press

-

c synonymous with inequality

-

d a relative term

-

e never the result of school exclusion.

-

-

2 Social exclusion is ‘dynamic’, meaning that:

-

a once people have been excluded they remain that way

-

b exclusion is passed from one generation to the next

-

c people move in and out of exclusion

-

d exclusion leads to greater social mobility

-

e excluded people become demotivated.

-

-

3 The transactional dimension of social exclusion means that:

-

a exclusion is detrimental to society as well as to the excluded individuals

-

b direct payments are the most effective intervention

-

c only interpersonal relationships create exclusion

-

d social exclusion reinforces social cohesion

-

e a moral underclass leads to greater exclusion.

-

-

4 Mental health services promote social inclusion when they:

-

a admit patients voluntarily to hospital

-

b consult service users and carers about how to provide services

-

c provide day centres where patients can play music

-

d refer children and adolescents to specialist psychiatric units

-

e have separate dining areas for staff and patients.

-

-

5 Regarding social identity and contact theory:

-

a membership of social groups forms part of the self-concept

-

b positive biases are given towards the ‘out’ group

-

c discrimination and stigma lead to high self-esteem

-

d positive contact increases negative stereotypes

-

e contact theory cannot be applied to race and ethnicity.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F | a | T |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | T | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | F | c | F | c | F |

| d | T | d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F |

| e | F | e | F | e | F | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.