Introduction

Gastropods or gastropod-like mollusks with a sinistrally coiled (left-handed) shell are a small but conspicuous part of Ordovician benthic associations. Whereas modern gastropod shells are overwhelmingly dextrally coiled (right-handed), and sinistral morphs or populations with such shells are rare (Vermeji, Reference Vermeij1975; Robertson, Reference Robertson1993; Schilthuizen and Davidson, Reference Schilthuizen and Davidson2005), a number of lower Paleozoic groups have only sinistrally coiled shells (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960; Bandel, Reference Bandel1993; Ebbestad and Lefebvre, Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015). Most are considered gastropods, defined as mollusks distinguished by the early developmental process of torsion in which all organs of the mantle cavity are twisted (torted) through 180° relative to the head and foot of the animal.

After torsion, the morphologically right side (originally posterior) becomes the topographically left side (and vice versa) when viewed from above, and the mantle cavity lies in an anterior position over the head. Torsion produces marked asymmetry or reduction of the soft parts of the mantle cavity in many groups. In most gastropods, torsion is counterclockwise, which leaves the organs originally on the morphological right side largely intact, forming an anatomically dextral animal. In most cases, the anatomically dextral gastropods have dextrally coiled shells, whereas their anatomical mirror images (gastropods that are anatomically sinistral and have undergone clockwise torsion) have a sinistrally coiled shell. These ‘true’ sinistral gastropods are termed sinistral orthostrophic whereas those with a ‘regular’ dextral shell are termed dextral orthostrophic (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The relationships of shell coiling, internal anatomy, and coiling of the operculum: (1) dextral orthostrophy; (2) sinistral orthostrophy; (3) dextral hyperstrophy; (4) sinistral hyperstrophy. First column of each figure: stippled vertical line = axis of coiling; curved arrow = coiling direction of shell when oriented with spire up and aperture facing the viewer. Second column in each figure: stippled curved line = the anterior mantle cavity; black silhouette = single ctenidium (to illustrate post-torsional asymmetry); a = anus. Third column in each figure: curved arrow = coiling direction; operculum oriented with outside facing viewer and positioned as it would appear when shell is oriented with spire up.

A different arrangement occurs when the soft organs of a snail are morphologically dextral, but the shell coils sinistrally, a condition called dextral hyperstrophy. The opposite is sinistral hyperstrophy (sinistrally arranged organs, dextrally coiled shell; see Peel and Horný, Reference Peel and Horný1996 for a rare fossil example). To show this condition, hyperstrophic shells are illustrated with the apex down (Knight, Reference Knight1952). This places the aperture on the same side as in a corresponding orthostrophic form, which is typically illustrated with the apex up, the axis of coiling vertical, and the aperture facing the viewer. In effect, the hyperstrophic shell can be seen as coiling up the axis of coiling, rather than down as in an orthostrophic form (Fig. 1).

This condition is rare in Recent adult gastropods, although larval hyperstrophy (heterostrophy) can be widespread (Robertson, Reference Robertson1993). Heterostrophy occurs when coiling direction reverses at the transition between the larval and adult shell. A dextral orthostrophic shell can be derived from a sinistrally coiled protoconch in which the anatomy remains dextral (dextral hyperstrophic; Robertson, Reference Robertson1993). Among the large group of heterobranch gastropods (Carboniferous–Recent), larval heterostrophy is a synapomorphic trait (Haszprunar, Reference Haszprunar1984). Heterostrophy occurs in some fossil linages in the earliest teleoconch rather than at the transition from the larval shell. The coiling axis of the two stages can either be parallel (coaxial) or not (noncoaxial), with the oldest example of the latter occurring in the Devonian (Frýda and Ferrová, Reference Frýda and Ferrová2011). Frýda and Rohr (Reference Frýda and Rohr2006) showed coaxial heterostrophy in the Ordovician Macluritoidea Carpenter, Reference Carpenter1861, whereas both coaxial and noncoaxial heterostrophy are documented in the Silurian–Cretaceous Porcelloidea Koken in Zittel, Reference Zittel1895 (Bandel, Reference Bandel1993; Frýda, Reference Frýda1997; Frýda and Ferrová, Reference Frýda and Ferrová2011; Frýda et al., Reference Frýda, Ebbestad and Frýdová2019).

The Ordovician Maclurites Le Sueur, Reference Le Sueur1818 and its allies are dextral hyperstrophic; the aperture would appear to be to the left if the shell is oriented in the typical manner with the apex upward, but if the aperture is placed to the right, the shell coils naturally upward with the apex forming the functional base of the shell as a direct consequence of the mode of life. The interpretive limitation is that the inferred hyperstrophy of shells such as Maclurites is not evident from external appearance alone. In fossil material, it is often difficult to establish whether gastropods with a sinistrally coiled shell were sinistral orthostrophic or dextral hyperstrophic unless an operculum is associated. This is because the coiling direction of the operculum, when spiral and viewed exteriorly, is always opposite to the true coiling direction of the shell, i.e., counterclockwise if the conch is dextral and clockwise if the conch is sinistral. Indirectly, this reveals the morphological arrangement of the soft parts, because this is opposite to the coiling direction of the operculum. Yochelson (Reference Yochelson1984) discussed the limitations of inferring anatomy of soft parts relative to shell coiling, because a hyperstrophically coiled shell must not automatically be assumed to have hyperstrophic soft parts. The sinistral coiling of the Maclurites operculum, combined with the seemingly sinistrally coiled shell, demonstrates that the condition in this snail was dextral hyperstrophic. It should be noted that Frýda and Rohr (Reference Frýda and Rohr2006) showed a heterostrophic condition the Lower Ordovician macluritid Macluritella stantoni Kirk, Reference Kirk1927, with initial whorls coiling dextrally (suggesting dextral orthostrophy), and later whorls coiling sinistrally. The macluritoids thus might have had a dextral orthostrophic ancestor, with dextral hyperstrophy as a derived condition (Frýda and Rohr, Reference Frýda and Rohr2006).

In Devonian Tychobrahea Peel and Horný, Reference Peel and Horný1996, the conispiral shell appears to coil dextrally in a regular dextral orthostrophic way, but because the operculum also coils dextrally (clockwise), the condition was interpreted as sinistral hyperstrophic (Peel and Horný, Reference Peel and Horný1996). When placed with the apex down, the shell coils sinistrally up the axis of coiling and the snail itself was presumably morphologically sinistral.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between the orthostrophic and hyperstrophic conditions described above. Other diagrams of the various morphological orientations and combination discussed herein were discussed by Knight (Reference Knight1952), Peel (Reference Peel1986), Robertson (Reference Robertson1993), Peel and Horný (Reference Peel and Horný1996), Frýda and Rohr (Reference Frýda and Rohr2006), and Frýda (Reference Frýda and Talent2012).

In the present study, Catalanispira n. gen., with the species Catalanispira reinwaldti (Öpik, Reference Öpik1930) and Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., is described from the Middle and Upper Ordovician (Darriwilian and Sandbian) of northern Estonia and eastern United States, respectively. It is sinistrally coiled and placed within Catalanispirinae n. subfam. of the family Onychochilidae Koken in Koken and Perner, Reference Koken and Perner1925 of the order Mimospirida Dzik, Reference Dzik1983. These univalved mollusks comprise a group of entirely sinistrally coiled taxa known from the Cambrian–Devonian (Frýda, Reference Frýda and Talent2012), possibly extending into the Carboniferous (see Bandel, Reference Bandel2002, p. 47). However, their record is strongly biased toward the Ordovician where they constitute ~ 3% of known Ordovician gastropod and gastropod-like taxa (Frýda and Rohr, Reference Frýda and Rohr1999, 2004; Frýda, Reference Frýda and Talent2012; Ebbestad et al., Reference Ebbestad, Frýda, Wagner, Horný, Isakar, Stewart, Percival, Bertero, Rohr, Peel, Blodgett, Högström, Harper and Servais2013; Ebbestad and Lefebvre, Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015). Mimospirids have variably been classified as untorted mollusks in the class Paragastropoda (Linsley and Kier, Reference Linsley and Kier1984), only distantly related to gastropods (Wagner, Reference Wagner2002), as dextral hyperstrophic gastropods (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960 [pars.]; Horný, Reference Horný1964 [pars.]; Wängberg-Eriksson, Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979; Peel, Reference Peel1986), or as sinistral orthostrophic gastropods (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960 [pars.]; Horný, Reference Horný1964 [pars.]; Dzik, Reference Dzik1983, Reference Dzik, Pályi, Zucchi and Caglioti1999; Frýda, Reference Frýda1999, Reference Frýda2001, Reference Frýda and Talent2012; Frýda and Rohr, Reference Frýda, Rohr, Webby, Paris, Droser and Percival2004, Reference Frýda and Rohr2006; Frýda et al., Reference Frýda, Nützel, Wagner, Ponder and Lindberg2008). Current classifications regard them as basal gastropods of uncertain systematic position (Bouchet et al., Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Frýda, Hausdorf, Ponder, Valdes and Warén2005, Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Hausdorf, Kaim, Kano, Nützel, Parkhaev, Schrödl and Strong2017).

In addition to increasing the diversity of onychochilid mollusks, the new genus clarifies details of the early ontogeny and teleoconch morphology and partly elucidates relationships between onychochilids. Protoconch development in the group, previously only known from a few taxa, is described for Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp.

Geological setting

During the late Middle and early Late Ordovician, both Laurentia and Baltica occupied equatorial warm waters in a broadly carbonate-dominated depositional regime (Torsvik and Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017). Increased faunal exchange is evident, although both areas maintain their faunal integrity reflected in the recognition of different faunal provinces defined mainly on shared endemic brachiopod taxa (Harper et al., Reference Harper, Rasmussen, Liljeroth, Blodgett, Candela, Jin, Percival, Rong, Villas, Zhan, Harper and Servais2013). Laurentia in the west and Australia in the east, and areas in between, belonged to a broad east-west equatorial low-latitude province, whereas Baltica was part of the Anglo-Welsh Baltic province, together with Avalonia and North and South China.

Upper Ordovician geology and stratigraphy, eastern United States

The Platteville Formation is part of a vast Upper Ordovician carbonate platform extending across midcontinent North America (Kolata et al., Reference Kolata, Huff and Bergström1996). The formation consists largely of fossiliferous lime mudstone and wackestone, locally dolomitized, and exposed in outcrops in northern Illinois, eastern and southwestern Wisconsin, northeastern Iowa, and southeastern Minnesota. Within the outcrop belt, it ranges in thickness from 6 to 42 m. Based on conodont biostratigraphy, the Platteville Formation lies entirely within the Phragmodus undatus Biozone (Sweet, Reference Sweet and Bruton1984, Reference Sweet and Sloan1987; Leslie, Reference Leslie2000; Leslie and Bergström, Reference Leslie, Bergström, Ludvigson and Bunker2005). Regional correlations based on chemical fingerprinting of K-bentonite beds and tracing on gamma ray logs show that the Platteville Formation lies below the Millbrig K-bentonite Bed throughout its extent (Kolata et al., Reference Kolata, Frost and Huff1986, Reference Kolata, Frost and Huff1987, Reference Kolata, Huff and Bergström1996, Reference Kolata, Huff and Bergström1998). The Millbrig K-bentonite is a confirmed Ordovician Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) marking the boundary between the Turinian and Chatfieldian stages of North America (Bergstrom et al., Reference Bergström, Chen, Gutiérrez-Marco and Dronov2009) and has been dated to 452.86 ± 0.29 Ma (Sell et al., Reference Sell, Ainsaar and Leslie2013). These stratigraphic relations support assignment of the Platteville Formation to the North American Turinian Stage of the Mohawkian Series and the global Sandbian Stage of the Upper Ordovician Series.

Near Dixon, in northern Illinois, five members are recognized within the Platteville Formation, including, in ascending order, the Pecatonica, Mifflin, Grand Detour, Nachusa, and Quimbys Mill. In this region, the formation has a consistent thickness of ~ 40 m and is well exposed in numerous open pit mines on the northern side of Dixon, most of which were developed by a succession of cement manufacturers over the last 150 years. There, the Mifflin Member consists of 5.5 m of thin, wavy, nodular beds containing a diverse, abundant, and well-preserved invertebrate fauna. Particularly notable are several localized pockets of unconsolidated marl formed by diagenetic alteration of the limestone. Fossils in these deposits tend to weather free of matrix. Nine well-preserved specimens of Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. were recovered from the marl deposits for this study.

Upper Middle and lower Upper Ordovician geology and stratigraphy: Baltoscandia

The upper Middle and lower Upper Ordovician of Baltoscandia is characterized by distinct facies zones from west to east, with deeper water facies in the western, southwestern, and southern parts and a shallower carbonate platform to the north and northeast (Jaanusson, Reference Jaanusson1973, Reference Jaanusson1995; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Sheehan, Ainsaar, Hints, Männik, Nõlvak and Rubel2004; Meidla et al., Reference Meidla, Ainsaar, Hints, Bauert, Hints, Meidla and Männik2014) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Maps and stratigraphy: (1) Estonia with Scandinavia as inset; (2) USA with position of Illinois; (3) state of Illinois with location of Dixon county (box); (4) correlation between the late Middle−Upper Ordovician of Estonia and the Upper Ordovician of northern Illinois. Note that the scales for Estonia and Illinois are the same. See text for references to the stratigraphy. An., Angochitina (Subzone); Amorph., Amporhognathus; Ar., Armoricochitina (Subzone); B., Baltinodus; Belod. comp., Belodina compressa; Chatf., Chatfieldian; Kat., Katian; L., Laufeldochitina; Lag., Lagenochitina (Subzone); Las., Lasnamägi; Sz., Subzone; Z., Zone.

In the central part of Baltoscandia, argillaceous limestones of the Furudal and Dalby limestones occur at the Darriwilian-Sandbian transition, with a total thickness of ~ 30 m (Ebbestad and Högström, Reference Ebbestad, Högström, Ebbestad, Wickström and Högström2007; Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Calner, Lehnert and Noor2011). The top of the Dalby Formation is marked by the Kinnekulle K-bentonite, recently dated to 454.06 ± 0.43 Ma (Ballo et al., Reference Ballo, Augland, Hammer and Svensen2019). The Kinnekulle and Millbrig K-bentonites have been considered coeval (Huff et al., Reference Huff, Bergström and Kolata2010; Huff, Reference Huff2016) but recent dating suggests that the former is older (Sell et al., Reference Sell, Ainsaar and Leslie2013; Bauert et al., Reference Bauert, Isozaki, Holmer, Aoki, Sakata and Hirata2014; Ballo et al., Reference Ballo, Augland, Hammer and Svensen2019; Oruche et al., Reference Oruche, Dix and Gazdewich2019).

Conodonts of the Baltoniodus alobatus Subzone of the Amorphognathus tvaerensis Biozone extend close to the Kinnekulle K-bentonite, which also marks the base of the Keila regional stage (Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Calner, Lehnert and Noor2011). The Dalby Formation contains a rich and diverse fauna (see references by Ebbestad and Högström, Reference Ebbestad, Högström, Ebbestad, Wickström and Högström2007) and Laeogyra reinwaldti (Öpik, Reference Öpik1930) was reported from the Dalby Limestone in Dalarna by Frisk and Ebbestad (Reference Frisk and Ebbestad2007). The unit is well-constrained biostratigraphically, encompassing the Kukruse and Haljala regional stages, with the base of the A. tvaerensis Zone appearing close to the base of the Dalby Limestone (Bergström, Reference Bergström, Ebbestad, Wickström and Högström2007). Although the conodont species is not confidently identified in Sweden, but found in Estonia, the base of the Amorphognathus inaequalis Biozone was taken to be at the base of the Dalby Limestone (Bergström, Reference Bergström, Ebbestad, Wickström and Högström2007; Bergström et al., Reference Bergström, Calner, Lehnert and Noor2011). Formerly, it was used as a subzone of the Pygodus anserinus Biozone, but Viira (Reference Viira2008) proposed to elevate it to biozone level.

Toward the east, shelf carbonates dominate the Estonian shelf area (northern Estonian facies belt), with contemporary strata to the Swedish Furudal and Dalby limestones being represented by the Kõrgekallas and Viivikonna formations (Uhaku and Kukruse regional stages, respectively). The latter unit is composed of argillaceous limestones with intercalations of the kukersite oil shale, and it holds the most diverse faunal assemblages in the Ordovician succession in Estonia (Hints, Reference Hints, Raukas and Teedumäe1997). Öpik (Reference Öpik1930) erroneously reported Clisospira reinwaldti Öpik, Reference Öpik1930 from this unit. It is only 3 m thick in the northwestern outcrop area and ~ 20 m thick in the northeastern area, but it has wide regional extent and forms the so-called Baltic Oil Shale Basin (Bauert and Kattai, Reference Bauert, Kattai, Raukas and Teedumäe1997) (Fig. 2).

The lower boundary of the Viivikonna Formation is very close to the Darriwilian–Sandbian boundary, identified by chitinozoans of the Eisenackitina rhenana Subzone and conodonts of the A. inaequalis Zone. The uppermost part lies within the Baltoniodus gerdae Subzone and the lower range of the Diplograptus foliaceous Biozone, although the upper part is missing in northeastern Estonia (Hints, Reference Hints, Raukas and Teedumäe1997; Nõlvak et al., Reference Nõlvak, Hints and Männik2006; Viira, Reference Viira2008; Hints et al., Reference Hints2010). The Kõrgekallas Formation is a thin-bedded argillaceous limestone unit in the upper part of the Uhaku Stage. It is only ~ 2 m thick in the northwestern outcrop area and ~ 18 m thick in the northeastern part (Hints, Reference Hints, Raukas and Teedumäe1997). Within the Baltic Oil Shale Basin, the upper beds (Pärtlioru Member) contain the oldest kukersite in Estonia. Except for its lowermost part, the formation falls within the P. anserinus conodont Zone and the Conochitina tuberculata chitinozoan Biozone (Hints, Reference Hints, Raukas and Teedumäe1997; Nõlvak et al., Reference Nõlvak, Hints and Männik2006; Viira, Reference Viira2008).

Locality information

Specimens of Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. were collected at two sites near Dixon, Illinois: Dixon site 1, a reclaimed quarry 2.0 km north of the intersection of White Oak Lane and Illinois State Route 2 (41°52’29.40”N, 89°27’2.34”W); Dixon site 2, an abandoned quarry 2.60 km north of the intersection of White Oak Lane and Illinois State Route 2 (41°53’40.41”N, 89°26’56.0”W). The single specimen of Catalanispira reinwaldti came from a now-vanished quarry at the southern lighthouse near Tallinn, Estonia. See Figure 2 for further details.

The Mimospirida, with emphasis on the Onychochilidae

Classification

Ebbestad and Lefebvre (Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015) discussed the current and reduced concept of Paragastropoda, with the order Hyperstrophina of Linsley and Kier (Reference Linsley and Kier1984) encompassing only the Clisospiridae Miller, Reference Miller1889 and Onychochilidae Koken in Koken and Perner, Reference Koken and Perner1925. It was pointed out that it corresponds to the Mimospirina of Dzik (Reference Dzik1983), making Hyperstrophina a junior objective synonym. Ebbestad and Lefebvre (Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015) proposed to elevate the suborder Mimospirina to order Mimospirida. Bouchet et al. (Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Frýda, Hausdorf, Ponder, Valdes and Warén2005, Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Hausdorf, Kaim, Kano, Nützel, Parkhaev, Schrödl and Strong2017) correctly assigned the two families to the superfamily Clisospiroidea, which is a senior objective synonym of the Onychochiloidea as introduced by Linsley and Kier (Reference Linsley and Kier1984). Bouchet et al. (Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Frýda, Hausdorf, Ponder, Valdes and Warén2005, Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Hausdorf, Kaim, Kano, Nützel, Parkhaev, Schrödl and Strong2017) also equaled the superfamily to the suborder Mimospirina, but because these are of different ranks, the placement of the superfamily in the order Mimospirida, as suggested by Ebbestad and Lefebvre (Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015), is followed here. Fryda and Bouchet in Bouchet et al. (Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Frýda, Hausdorf, Ponder, Valdes and Warén2005), Frýda (Reference Frýda and Talent2012), and Bouchet et al. (Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Hausdorf, Kaim, Kano, Nützel, Parkhaev, Schrödl and Strong2017) classified the Clisospiroidea as basal gastropods of uncertain systematic position, instead of the (paraphyletic) class Paragastropoda as proposed by Linsley and Kier (Reference Linsley and Kier1984) (Table 1). It has been argued that the sinistral asymmetry of the embryonic protoconch 1 shows that they could not be hyperstrophic (Dzik, Reference Dzik1983, Reference Dzik, Pályi, Zucchi and Caglioti1999), implying sinistral orthostrophy, and that other compelling evidence, e.g., an operculum, to demonstrate this condition is lacking (Frýda, Reference Frýda1995, Reference Frýda and Talent2012; Frýda and Blodgett, Reference Frýda and Blodgett2001; Frýda and Rohr, Reference Frýda, Rohr, Webby, Paris, Droser and Percival2004, 2006; Frýda et al., Reference Frýda, Nützel, Wagner, Ponder and Lindberg2008).

Table 1. Various classification schemes of taxa in the Clisospiroidea. The Devonian (D) Progalerinae was not discussed by Horný (Reference Horný1964) who only looked at the lower Paleozoic taxa; subsequently, Progalerinae was considered a junior synonym of Clisospirinae (Bouchet et al., Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Frýda, Hausdorf, Ponder, Valdes and Warén2005). Only modern family and subfamily endings are used here.

The Clisospiroidea, as proposed by Bouchet et al. (Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Frýda, Hausdorf, Ponder, Valdes and Warén2005, Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Hausdorf, Kaim, Kano, Nützel, Parkhaev, Schrödl and Strong2017), is largely a summary of the proposals by Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960) and Horný (Reference Horný1964) (see Table 1). Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960) placed the subfamilies Clisospirinae and Progalerinae Knight, Reference Knight1956 in the family Clisospiridae of the superfamily Clisospiroidea (as Clisospiracea), and the subfamilies Onychochilinae and Scaevogyrinae Wenz, Reference Wenz and Schindewolf1938 within the family Onychochilidae in the superfamily Macluritoidea (as Macluritacea). Like Wenz (Reference Wenz and Schindewolf1938), Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960) did not recognize similarities between the two families, but Horný (Reference Horný1964) found that the Onychochilidae and the Clisospiridae were closely related sinistral and hyperstrophic gastropods. He added Atracurinae Horný, Reference Horný1964 and Trochoclisinae Horný, Reference Horný1964 to the Clisospiridae, and Hyperstropheminae Horný, Reference Horný1964 to the Onychochilidae.

Dzik (Reference Dzik1983) proposed to unite the two families in the suborder Mimospirina, without superfamily rank, and remarked that further subdivisions into subfamilies seemed difficult. Linsley and Kier (Reference Linsley and Kier1984) maintained the family structure for the Clisospiridae but did not provide subfamilies for the Onychochilidae (Table 1). They united these two in the superfamily Onychochiloidea (as Onychochilacea), although the previously named Clisospiroidea would have priority, in their new order Hyperstrophina of the class Paragastropoda. Previous classification of the group by Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960) within the Macluritida was contested by Dzik (Reference Dzik1983) and later firmly refuted by Frýda and Rohr (Reference Frýda and Rohr2006); see also discussion by Morris (Reference Morris1991) and Wagner (Reference Wagner2001, Reference Wagner2002).

Webers et al. (Reference Webers, Pojeta and Yochelson1992) proposed to return the largely Cambrian Scaevogyridae to family rank (subfamily by Knight et al., Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960; Bouchet et al., Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Frýda, Hausdorf, Ponder, Valdes and Warén2005, Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Hausdorf, Kaim, Kano, Nützel, Parkhaev, Schrödl and Strong2017) and that Onychochilidae could be an incertae sedis form taxon for Ordovician and younger sinistral forms of uncertain relationship.

Composition of the Onychochilidae

The currently recognized subfamilies within the Onychochilidae are the Onychochilinae Koken in Koken and Perner, Reference Koken and Perner1925, the Scaevogyrinae Wenz, Reference Wenz and Schindewolf1938, and the Hyperstropheminae Horný, Reference Horný1964. The last contains only the tiny Devonian Hyperstrophema devonicans Horný, Reference Horný1964, known from only two specimens.

Ebbestad and Lefebvre (Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015) included 14 Cambrian (Furongian) to Devonian genera in the Onychochilidae, without assignment to subfamilies. Pervertina Horný, Reference Horný1964, known from two Upper Ordovician specimens (one in Sweden and one in the Czech Republic), was erroneously included in lieu of Antispira Perner, Reference Perner1903, acknowledged by the authors as a junior synonym of Antispira following Frýda and Rohr (Reference Frýda and Rohr1999).

Wenz (Reference Wenz and Schindewolf1938) included only the Silurian Onychochilus Lindström, Reference Lindström1884 in the Onychochilidae, moving the three other genera originally included in the family by Koken and Perner (Reference Koken and Perner1925) to other families: Mimospira Koken in Koken and Perner, Reference Koken and Perner1925 to the Clisospiridae and Laeogyra Perner, Reference Perner1903 and Helicotis Koken in Koken and Perner, Reference Koken and Perner1925 to his new family Scaevogyridae. There, he also placed Scaevogyra Whitfield, Reference Whitfield1878, Versispira Perner, Reference Perner1903 (as a subgenus of Scaevogyra), Antispira (tentatively), Matherella Walcott, Reference Walcott1912, Matherellina Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1933, and (tentatively) Palaeopupa Foerste, Reference Foerste1893, the last two as subgenera of Matherella. Subsequently, Palaeopupa was regarded an objective synonym of Onychochilus by Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960).

The families of Wenz (Reference Wenz and Schindewolf1938) were significantly revised by Knight et al. (Reference Knight, Cox, Keen, Batten, Yochelson, Robertson and Moore1960) in the ‘Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology.’ In a preamble to the Treatise work, Knight (Reference Knight1952, p. 2) regarded many of the families and subfamilies of Wenz as polyphyletic, although the reconstructed relationships in the Treatise might not have been much of an improvement. Scaevogyridae Wenz, Reference Wenz and Schindewolf1938 was included as a subfamily in the Onychochilidae, with Kobayashiella Endo, Reference Endo1937 added. Laeogyra, Matherella, and Matherellina were placed with Onychochilus in the subfamily Onychochilinae, also adding the Devonian Sinistracirsa Cossmann, Reference Cossmann1908. Wängberg-Eriksson (Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979) later added her new genera Bodospira Wängberg-Eriksson, Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979, Angulospira Wängberg-Eriksson, Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979, and Tapinogyra Wängberg-Eriksson, Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979 from the Boda Limestone (Upper Ordovician) of central Sweden, but at family level only. A further inclusion was the Devonian Voskopiella Frýda, Reference Frýda1992.

Webers et al. (Reference Webers, Pojeta and Yochelson1992) resurrected Scaevogyridae with a composition closer to that of Wenz (Reference Wenz and Schindewolf1938), including Scaevogyra, Matherella, Matherellina, and Kobayashiella. The poorly known, and possibly synonomyous, genera Versispira and Antispira from the Ordovician of the Prague Basin were left unranked.

The widely differing opinions on the construction and composition of the Clisospiroidea mostly reflect our still very limited knowledge of most members of the group, and lack of details (e.g., the protoconch) or even clues to the question of hyperstrophy. Although it therefore seems prudent now to avoid major revisions of subfamilies, a new subfamily is introduced in the present study. This is justified by apomorphies in the protoconch and teleoconch that are not compatible with placement in any of the currently recognized subfamilies (see Systematic paleontology).

Distribution of onychochilids

Frýda and Rohr (Reference Frýda and Rohr1999) presented the paleobiogeography of Ordovician Clisospiridae and Onychochilidae and discussed most of the taxa known at that time. Ebbestad and Lefebvre (Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015) gave the distribution of 41 Cambrian (Furongian) and Ordovician onychochilid species when describing the new genus Pelecyogyra Ebbestad and Lefebvre, Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015 from Morocco, the first onychochilid taxon identified from the Mediterranean margin of Gondwana. Recently the genus has also been identified in the Ordovician of Montagne Noire, France (Ebbestad et al., Reference Ebbestad, Lefebvre, Kundura and Kundurain press), which, together with a record of Mimospira by Sdzuy et al. (Reference Sdzuy, Hammann and Villas2001) from Frankenwald in Germany, represents the only records of the group in the Armorican terrane. An unidentified onychochilid was identified by Rohr et al. (Reference Rohr, Beresi and Yochelson2001) in Ordovician strata of the Precordillera of South America, representing the Proto-Andean margin of Gondwana, and Dzik (Reference Dzik2020) firmly identified clisospirid taxa in the Ordovician of Argentina.

The record of onychochilids and clisospirids is strongly biased toward the Ordovician (Frýda and Rohr, Reference Frýda and Rohr1999; Ebbestad et al., Reference Ebbestad, Frýda, Wagner, Horný, Isakar, Stewart, Percival, Bertero, Rohr, Peel, Blodgett, Högström, Harper and Servais2013; Ebbestad and Lefebvre, Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015), but during the latest Cambrian (Furongian), several onychochilid genera were already widespread in Antarctica, North China, and eastern North America (Ebbestad and Lefebvre, Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015, fig. 6), with older occurrences of Kobayashiella? in the Miaolingian of Australia (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Brock and Paterson2019). Already in the Lower Ordovician and onward, they become rare in these areas. Instead, clisospirid and onychochilid taxa are widespread from the Dapingian onward in Perunica (Prague Basin) and Baltica (Baltoscandia), with particularly the Katian Boda Limestone representing a hot spot (Frýda and Rohr, Reference Frýda and Rohr1999; Ebbestad et al., Reference Ebbestad, Frýda, Wagner, Horný, Isakar, Stewart, Percival, Bertero, Rohr, Peel, Blodgett, Högström, Harper and Servais2013; Ebbestad and Lefebvre, Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015).

Clisospiroid generic diversity was low in the Early to Middle Ordovician, increasing markedly from the Darriwilian onward until an abrupt extinction phase at the end of the Ordovician (Frýda and Rohr, Reference Frýda, Rohr, Webby, Paris, Droser and Percival2004; Frýda, Reference Frýda and Talent2012; Ebbestad et al., Reference Ebbestad, Frýda, Wagner, Horný, Isakar, Stewart, Percival, Bertero, Rohr, Peel, Blodgett, Högström, Harper and Servais2013). Clisospira and Mimospira survived into the Silurian (Peel, Reference Peel1975, Reference Peel1986; Wängberg-Eriksson, Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979), with new taxa emerging, e.g., Angulospira, Conclisa Horný, Reference Horný1964, and Onychochilus. Occurrences in Perunica and Baltica still prevailed, but with a few taxa also found in eastern North America and North Greenland. Six Devonian taxa are attributed to the clisospiroids (asterisks mark members of the Onychochilidae), all from central Europe (Czech Republic and one from Germany): Antigyra Horný, Reference Horný1964, Atracura Horný, Reference Horný1964, *Hyperstrophema Horný, Reference Horný1964, *Sinistracirsa, *Sinistriconcha Heidelberger and Bandel, Reference Heidelberger and Bandel1999, Trochoclisa Horný, Reference Horný1964, and *Voskopiella. A single species of *Onychochilus was reported by Yoo (Reference Yoo1988) from the Lower Carboniferous of Australia, and later moved to Sinistriconcha by Bandel (Reference Bandel2002).

Material and methods

Nine specimens of Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. from the upper midwestern United States and one specimen of Catalanispira reinwaldti from northern Estonia were available for this study. The specimens assigned to Laeogyra reinwaldti by Frisk and Ebbestad (Reference Frisk and Ebbestad2007) from the Dalby Limestone of central Sweden are not conspecific with Catalanispira reinwaldti and are here tentatively assigned to Laeogyra sp. All specimens were largely free from the matrix and only minor cleaning and development of the umbilical areas were necessary. Specimen PRI 76976 of Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. was sectioned to provide a median transverse cross section of the whorls (Fig. 3). The rate of whorl expansion (W) is based on Raup (Reference Raup1966) and calculated by dividing the width:length ratio of two consecutive whorls. The resulting cross section was photographed under ethanol and a drawing was traced from this to prepare a figure. The base of the single specimen of Catalanispira reinwaldti was obscured by matrix and was mechanically prepared to reveal the umbilical side and part of the aperture. All specimens were coated with ammonium chloride prior to photography. Taxonomy follows Frýda and Bouchet in Bouchet et al. (Reference Bouchet, Rocroi, Frýda, Hausdorf, Ponder, Valdes and Warén2005). The descriptive term ‘apical cap’ is taken from Warén and Gofas (Reference Warén and Gofas1996).

Figure 3. Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., PRI 76976 (cross section), from base of Mifflin Member, Platteville Formation (Diplograptus foliaceous Biozone, Turinian regional Stage, Sandbian 2), northern Illinois, eastern USA. Shaded area = whorls filled with recrystallized calcite. Arrow points at base of whorl.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Specimens of Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. are deposited in the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution of Ithaca, New York, USA (PRI 76973–76977, Dixon site 1) and the University of Illinois Paleontological Collections, USA (ISGS 1017–1020, Dixon site 2). Catalanispira reinwaldti is deposited in the Natural History Museum, University of Tartu, Estonia (TUG 1053-13).

Systematic paleontology

Order Mimospirida Dzik, Reference Dzik1983

Family Onychochilidae Koken in Koken and Perner, Reference Koken and Perner1925

Subfamily Catalanispirinae new subfamily

Included genera

Catalanispira new genus (and type genus, designated here); Pelecyogyra Ebbestad and Lefebvre, Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015.

Diagnosis

Sinistral, low trochiform shell with rapid whorl expansion, a deep funnel-like umbilicus, narrow elliptical aperture, and large cap-shaped protoconch.

Remarks

Catalanispirinae n. subfam. differs from other subfamilies of the Clisospiroidea by its relatively large shell that can reach nearly 30 mm wide, the low trochiform shape, the narrow elliptical aperture, and large cap-shaped protoconch. The upper surface in all included taxa has fine commarginal ornamentation overlying an irregular and uneven, softly plicate shell surface, most strongly developed in Pelecyogyra. All apomorphies are known in the type species Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., but all are not preserved in the Estonian species Catalanispira reinwaldti or the Tremadocian Pelecyogyra known from Morocco and France (Ebbestad and Lefebvre, Reference Ebbestad and Lefebvre2015; Ebbestad et al., Reference Ebbestad, Lefebvre, Kundura and Kundurain press). The latter is distinguished by the relatively large, low trochiform shell (although compressed), the widely expanding last whorl (although the exact nature of the aperture is unknown), and a large protoconch (although its precise shape is not preserved), which suggest a placement within the new subfamily rather than any of the other three existing subfamilies.

The Devonian Hyperstrophema, single member of the subfamily Hyperstropheminae, bears some overall morphological resemblance to the Ordovician taxa, but is tiny with a much smaller protoconch, more rounded whorl profile, and strong, regular spiral and commarginal ornamentation.

Genus Catalanispira new genus

Type species

Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., by original designation.

Other species

Catalanispira reinwaldti (Öpik, Reference Öpik1930).

Diagnosis

Shell low trochiform with 2.5 sinistrally coiled and rapidly expanding whorls; whorl expansion rate (W) ~ 2; whorl profile narrow lenticular with width ~ 1/3 of height; whorls steeply inclined; umbilical area deep, funnel-like. Protoconch large (> 1 mm across), cap-shaped, and with ornamentation (if present) differing from the teleoconch. Base of aperture falcate, projecting anteriorly. Ornamentation of fine sharp growth lines on upper whorl surface and coarser falcate lines on umbilical surface.

Occurrence

Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. is found in the lower 2 m of the Mifflin Member of the Platteville Formation (Diplograptus foliaceous Biozone, Turinian regional Stage, Sandbian 2) in northern Illinois, eastern United States. Catalanispira reinwaldti is found in the Middle Ordovician Pärtlioru Member of the Kõrgekallas Formation (Darriwilian; Uhaku regional stage), northern Estonia.

Etymology

Named after Mr. John A. Catalani, Woodridge Grove, Illinois, in recognition of his generous contributions for more than 40 years to paleontology and to professional paleontologists.

Remarks

Catalanispira n. gen. has some resemblance to species of Scaevogyra in the low shell and expansion of the whorls, but the latter have a more naticid-shaped shell, flared aperture in some species, and a more rounded outline of the whorl. Forms like Matherella and Matherellina have a higher spire and a much shallower umbilicus. Low-spired species of Laeogyra and Kobayashiella have a somewhat similar shell shape and seemingly a deep umbilicus, but the whorls and whorl profile are much more rounded and ornamentation on the upper whorl surface consists of sharply defined commarginal ribs.

Catalanispira plattevillensis new species

Figures 3–7

Figure 4. Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., from base of Mifflin Member, Platteville Formation (Diplograptus foliaceous Biozone, Turinian regional Stage, Sandbian 2), northern Illinois, eastern USA: (1–6) holotype, ISGS PRI 76973, in dorsal (1), lateral (2), ventral (3), apertural (4), and ventral oblique (5) views, and detail of adumbilical part of inner lip (6); (7–9) PRI 76977, in dorsal (7), apertural (8), and dorsal oblique (9) views. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Figure 5. Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., from base of Mifflin Member, Platteville Formation (Diplograptus foliaceous Biozone, Turinian regional Stage, Sandbian 2), northern Illinois, eastern USA: (1–7) ISGS 1020, in dorsal (1), lateral oblique (2), and various lateral (3−5) views, and detail of protoconch (6, 7); (8, 9) PRI 76975, in dorsal (8) and lateral (9) views, showing boundary of protoconch (arrow in 8), and shell damage and repair (arrow in 9). See Figure 6.1–6.3 for entire specimen. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Figure 6. Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., from base of Mifflin Member, Platteville Formation (Diplograptus foliaceous Biozone, Turinian regional Stage, Sandbian 2), northern Illinois, eastern USA: (1–3) PRI 76975, in dorsal (1), lateral (2), and oblique (3) views; the shell in (2) is oriented to show the approximate left lateral view of shell in life position; see Figure 5.8 and 5.9 for details of apex and shell repair; (4–8) ISGS 1017, in dorsal (4), ventral oblique (5), dorsal oblique (6), and lateral (7) views; white arrow in (4) points to the halt in growth; shell in (8) oriented to show approximate left lateral view of shell in life position. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Figure 7. Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., from base of Mifflin Member, Platteville Formation (Diplograptus foliaceous Biozone, Turinian regional Stage, Sandbian 2), northern Illinois, eastern USA: (1–5) PRI 76974, in dorsal (1), lateral (2), ventral (3), ventral oblique (4), and apertural (5) views; note falcate shape of inner lip; (6–8) ISGS 1019, in dorsal (6), lateral (7), and dorsal oblique (8) views; white arrow in (6) points to the marked halt in growth after approximately one whorl. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Diagnosis

A species of Catalanispira with steeply inclined whorls. Last whorl with increased rate of translation so that periphery of previous whorl is at or slightly above suture. Apertural plane at an angle of ~ 63° relative to axis of coiling. Size < 15 mm.

Description

Shell trochiform, slightly wider than high with maximum width 14 mm. Shell consisting of 2.5 sinistrally coiled, rapidly expanding whorls. Rate of translation low with incremental angle of 90° and whorl expansion rate (W) ~ 2. Whorl profile narrow, symmetrically lenticular, with width ~ 1/3 of height. Peripheral margin sharply rounded, representing lowest point on whorl. Upper whorl surface and umbilical surface steeply inclined (~ 45° relative to axis of coiling), creating deep, open, funnel-like umbilical area. Whorls adpressed, but because they are steeply inclined and lenticular, whorls barely touching along upper third and imbricated roof-like tiles. In some specimens, last whorl not abutting penultimate whorl abaxially, creating small overhang at suture with groove underneath, suggesting slight increase in rate of translation of last whorl. Aperture tangential, with apertural plane at angle of ~ 63° relative to axis of coiling. Shell thin, perhaps a bit thicker on upper surface and at adapical end of whorl. Ornamentation on upper surface consisting of fine, densely spaced, sharp commarginal growth lines curving backward in wide crescent. Secondary ornamental component consisting of irregularly spaced, subdued ridges underlying and paralleling growth lines, giving somewhat plicate appearance. Growth lines on umbilical surface opisthocline with marked falcate shape, densely spaced, standing out as simple, slightly pronounced, rounded lines. Base of aperture with strong anterior projection. Inner margin and apertural lip reflected, slender, and rod-like, extending from deepest part of umbilicus along approximately half the distance of the margin. Protoconch large, cap-shaped, 1.4 mm wide, ~ 0.5 mm high; ornament obscure, but faint lines subparallel to basal margin can be present. Base circular in outline with apex slightly to one side (adaxially), suggesting sinistral coiling. Apical cap separated from teleoconch by sharp boundary accompanied by change in coiling and ornamentation of succeeding shell. Axis of coiling in the two ontogenetic stages does not seem to coincide. Fine growth lines on teleoconch curving adaperturally at angle of ~ 25–30° relative to plane of apical cap.

Etymology

The species is named after the Platteville Formation in which it occurs.

Materials

Besides the holotype, eight specimens are known (PRI 76974–76977, Dixon site 1; ISGS 1017–1020, Dixon site 2), all from the Mifflin Member, Platteville Formation, 2 m above the Pecatonica Member.

Remarks

Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. has a remarkable shell with its narrow lenticular aperture and deep funnel-like umbilical area, presented in a sinistrally coiled guise. The whorls are barely touching but overlapping in a characteristic tile-like manner (Fig. 3). The deep falcate shape and anterior projection of the base of the aperture (Figs. 4.3, 7.3) create a basal excavation reminiscent of the excavated sinus seen in some pychnomphalines or the euomphalid Centrifugus Bronn, Reference Bronn1835 and others, a feature that could provide space for the foot extending from the aperture. Convergent similarities in the anterior projection and excavation of the base, the tangential aperture, and low, trochiform shell afford striking comparisons with species of Silurian pseudophorids, e.g., Pseudophorus profundus (Lindström, Reference Lindström1884) from Gotland, Sweden, although that dextral orthostrophic taxon lacks the extreme elongation of the aperture and the funnel-like umbilical area.

The inner lip of the aperture extends deeply into the umbilicus and its margin has a thin, rod-like appearance adapically, and it thins to just the thin shell toward the base of the aperture (Figs. 4.5, 4.6, 7.4, 7.5). It can be seen as a strengthening feature at this section of the lip against the forces exerted by the foot during clamping or interaction with the substratum. The strength of such a foot against the substratum in a modern gastropod with an elongated aperture and a corresponding elongated foot is not great and often correlates with life on soft substrata (McNair et al., Reference McNair, Kier, Lacroix and Linsley1981).

Runnegar (Reference Runnegar1981; see also Runnegar and Pojeta, Reference Runnegar, Pojeta, Trueman and Clarke1985, p. 36) argued that Scaevogyra and Matherella had lost one gill, because they were quite large, had no sinus or slit, and had in the last whorl a muscle attached to the shell on the part facing outward. By extension, this could apply as well to other sinistral onychochiloids, although Dzik (Reference Dzik1983) speculated that they had paired organs. The strongly elongated aperture in Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. clearly supports the notion that only one gill was present.

The protoconch, observed with some details in specimens PRI 76975 and ISGS 1020 (Fig. 5), is low cap-shaped, probably unornamented, and separated by a distinct line from the coiled teleoconch. The term ‘apical cap’ was used by Wáren and Gofas (Reference Warén and Gofas1996) to describe the symmetrical embryonic shell (protoconch 1) of some Recent monoplacophorans, with a width up to 0.25 mm. The apical cap in Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. on the other hand is uncoiled, slightly asymmetrical, and large (1.4 mm wide). The bulbous, slightly coiled embryonic shells of archaeogastropods and Recent vetigastropods reach maxima of 0.8 mm wide (Nützel, Reference Nützel2014).

The sharp boundary and start of well-developed ornamentation clearly demarcate the apical cap as a protoconch, but it is not entirely clear whether the unusually large apical cap represent the embryonic shell or incorporates the larval shell (protoconch 2). Very faint lines on the side near the margin could suggest a degree of ornamentation present at least on parts of the apical cap (Fig. 5.7), which could suggest that this is part of the larval shell. Furthermore, the very apex of the best-preserved protoconch is exfoliated (Fig. 5.6) in an area ~ 350 μm wide. It is conceivable that this patch was originally occupied by an embryonic shell, and if so, such an arrangement would indicate the presence of both protoconchs 1 and 2. The larval shell in Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. differs from the protoconch of Mimospira, which could include a multiwhorled protoconch 2 (but see discussion).

Catalanispira reinwaldti (Öpik, Reference Öpik1930)

Figure 8

Reference Öpik1930 Clisospira reinwaldti Öpik, p. 25, pl. 2, fig. 12.

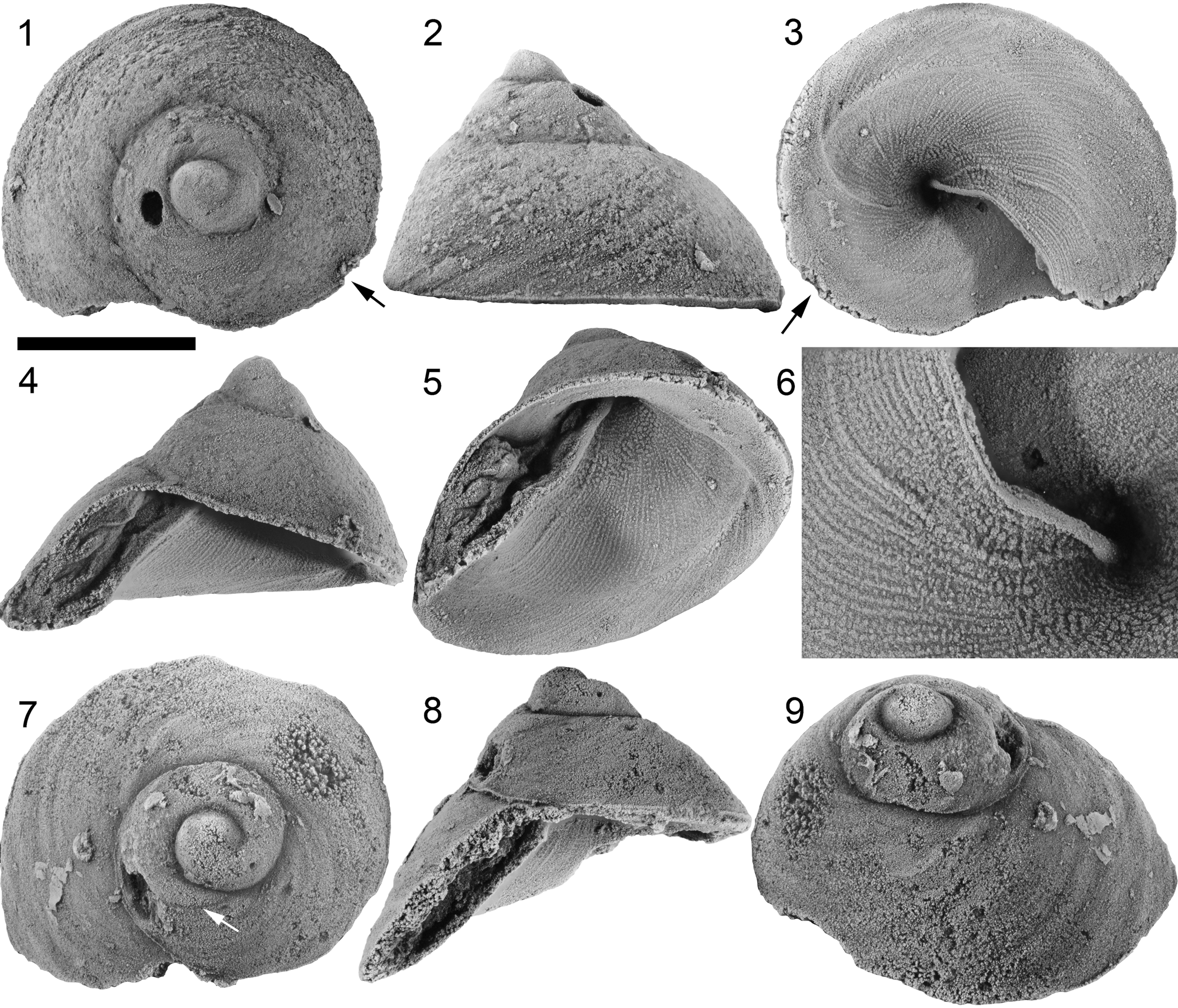

Figure 8. Catalanispira reinwaldti (Öpik, Reference Öpik1930), holotype, TUG 1053-13, from late Middle Ordovician Pärtlioru Member, Kõrgekallas Formation (Darriwilian; Uhaku regional stage), at no-longer-existing quarry at southern lighthouse, Tallinn, Harju County, northern Estonia, in dorsal (1), lateral (2), ventral (3), apertural (4), dorsal oblique (5), ventral oblique (6), apertural oblique (7), lateral (8), and lateral oblique (9) views. Scale bar = 10 mm.

Reference Rõõmusoks1970 Clisospira reinwaldti; Rõõmusoks, p. 94 (table 5), 122 (table 7).

Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979 Laeogyra? reinwaldti; Wängberg-Eriksson, p. 18, fig. 5i, j. non 2007 Laeogyra reinwaldti; Frisk and Ebbestad, p. 88, fig. 3E–H.

Holotype

TUG 1053-13, only known specimen, an internal mold from the late Middle Ordovician Pärtlioru Member of the Kõrgekallas Formation (Darriwilian; Uhaku regional stage) at a no-longer-existing quarry at the southern lighthouse in Tallinn, Harju County, northern Estonia.

Diagnosis

A large species of Catalanispira n. gen., with lower inclination of the outer whorl and last whorl overlapping the periphery of the previous whorl. Apical angle and rate of translation low; apertural plane inclined ~ 70° relative to the axis of coiling. Upper shell surface uneven with an irregular plicate appearance.

Description

Shell low, trochiform, rapidly expanding, with 2.5 whorls. Height ~ 2/3 of width; shell 28 mm wide. Incremental angle ~ 110°. Whorl profile narrowly lenticular, with width ~ 1/4 of height, steeply inclined upper whorl surface, and umbilical wall (~ 42° to axis of coiling), giving deep, open, funnel-like umbilicus. Apertural plane at angle of ~ 70° relative to axis of coiling. Periphery lowest point on whorl, evenly but sharply rounded adumbilically. Last whorl slightly overlapping periphery of previous whorl. Shell missing but upper surface with irregularly spaced, low plicate elevations paralleling growth lines, curving backward in wide arch.

Remarks

This Estonian species is known from a single internal mold, which is much larger than any specimen of Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. The whorl is less inclined than in the type species, and the last whorl slightly overlaps the previous one. In Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp., the last whorl instead seems to have an increased rate of translation. The apical angle and rate of translation in Catalanispira reinwaldti are thus lower than in Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. Shell and ornamentation are not preserved in Catalanispira reinwaldti, but growth lines are visible as impressions on the upper whorl surface of the mold, showing the same wide curvature as in Catalanispira plattevillensis.

Öpik (Reference Öpik1930) assigned the species to Clisospira Billings, Reference Billings1865, which is a medium to low-spired sinistral taxon with a distinct peripheral frill and cancellate ornamentation.

Öpik (Reference Öpik1930) reported the species from the Kukruse beds (CII) at the southern lighthouse in Tallinn, most likely because he recognized kukersite deposits there, but the beds at this site are of the Kõrgekallas Formation, which there had kukersite deposits in its upper part (personal communication, H. Bauert, 2019). This placement was also given by Rõõmusoks (Reference Rõõmusoks1970, p. 122) who reported the species from level CIca.

Discussion

Protoconch morphology

Much of the discussion concerning mimiospirid phylogeny centers on the interpretation of protoconch morphology of Mimospira. This is a small genus with a shell of up to six whorls. Some species, including the type species Mimospira helmhackeri (Perner, Reference Perner1900) can reach 7–9 mm in height (Knight, Reference Knight1941; Wängberg-Eriksson, Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979) but most taxa are no more than 1–4 mm. In total, ~ 20 species are described and, except for two Silurian occurrences, are Ordovician in age (Peel, Reference Peel1975, Reference Peel1986; Wängberg-Eriksson, Reference Wängberg-Eriksson1979; Frýda, Reference Frýda1989; Isakar and Peel, Reference Isakar and Peel1997; Frýda and Rohr, Reference Frýda and Rohr1999; Frisk and Ebbestad, Reference Frisk and Ebbestad2007; Dzik, Reference Dzik2020).

The protoconch of Mimospira seems to consist of an embryonic shell (protoconch 1) and a multiwhorled larval shell (protoconch 2). A two-stage protoconch is found in taxa with planktotrophic development, whereas a one-stage protoconch is found in basal gastropod clades with nonplanktotrophic development (Geiger et al., Reference Geiger, Nützel, Sasaki, Ponder and Lindberg2008; Nützel, Reference Nützel2014). Although size ranges overlap, a small embryonic shell generally indicates planktotrophic development, whereas a larger embryonic shell (0.1–0.8 mm in modern vetigastropods) is found in taxa with nonplanktotrophic development (Bandel, Reference Bandel1982; Geiger et al., Reference Geiger, Nützel, Sasaki, Ponder and Lindberg2008; Frýda, Reference Frýda and Talent2012; Nützel, Reference Nützel2014). Nonplanktotrophy could reflect the ancestral condition in gastropods, whereas planktotrophic development might have developed in the late Cambrian–Early Ordovician (Nützel et al., Reference Nützel, Lehnert and Fýda2006, Reference Nützel, Lehnert and Fýda2007; Nützel, Reference Nützel2014); Nützel et al. (Reference Nützel, Lehnert and Fýda2006, Reference Nützel, Lehnert and Fýda2007) applied a method to distinguish between embryonic shells with planktotrophic vs those with nonplanktotrophic development, in which the width 100 mm from the apex was used; a value < ~100 μm at this point could indicate planktotrophic development. The transition between protoconchs 1 and 2 is usually clearly marked by change in growth and start of or a change in ornamentation; the transition to the teleoconch, when the larva undergoes metamorphism, is abrupt (Nützel, Reference Nützel2014). However in fossil material, the boundary between the embryonic shell and the larval shell can be quite difficult to see (Nützel et al., Reference Nützel, Lehnert and Fýda2007).

Dzik (Reference Dzik1983) described the morphology of small specimens of Mimospira sp. mainly from internal molds. The single-whorled embryonic shell (protoconch 1) was shown to be 0.4 mm wide, after which there is a clear change in shape and ornamentation. Considerable variation in the number of whorls was described from subsequent whorls in what Dzik (Reference Dzik1983) referred to as juvenile shells. Dzik (Reference Dzik1983, p. 235) also stated that the embryonic shell is homostrophic with the teleoconch. It should be mentioned that the protoconch of the Silurian Mimospira abbea Peel, Reference Peel1975 was regarded as heterostrophic (Peel, Reference Peel1975).

Frýda (Reference Frýda1989) closely compared protoconch development in his new species, Mimospira barrandei Frýda, Reference Frýda1989, with that of Dzik's (Reference Dzik1983) material. He showed that the transition to an ornamented teleoconch appeared after 1.5 whorls in Mimospira barrandei at a width ~ 0.4 mm, and after slightly less than 2 whorls in Mimospira helmackeri but at greater width. Isakar and Peel (Reference Isakar and Peel1997) described a smooth, bulbous protoconch in Mimospira puhmuense Isakar and Peel, Reference Isakar and Peel1997 consisting of 1.5 whorls at a width of 0.4 mm, before the ensuing ornamented teleoconch reaching a height ~ 2 mm.

A two-staged protoconch in Mimopsira (embryonic + larval shell) as described by Dzik (Reference Dzik1983) would imply that the initial embryonic shell (0.4 mm wide) is followed by a multiwhorled larval shell of < 1 mm diameter. Larger specimens that could show the transition to a teleoconch are not preserved in Dzik's (Reference Dzik1983) material; however, it is possible to interpret the abrupt change in shape and ornamentation directly following the embryonic shell shown in a few well-preserved specimens (Dzik, Reference Dzik1983, fig. 3) as transitions to the teleoconch, in which case all of the small multiwhorled shells would be juvenile teleoconchs and not larval shells. By extension, the protoconchs discussed by Frýda (Reference Frýda1989) and Isakar and Peel (Reference Isakar and Peel1997) could also represent embryonic shells only. However in these examples, the transition to a teleoconch, as marked by the abrupt change in ornamentation, seems to follow after slightly more than one whorl. Therefore, because the embryonic shell (protoconch 1) consists of approximately one whorl (Nützel, Reference Nützel2014), it would seem that in these examples the embryonic shell is followed by an unornamented protoconch 2 before the ornamented teleoconch. However, an embryonic shell per se has not been clearly identified in the two last examples and, to paraphrase Nützel et al. (Reference Nützel, Lehnert and Fýda2007), whether these protoconchs represent larval shells (protoconch 2) in which the embryonic shells (protoconch 1) are obscured or just a large protoconch 1, remains ambiguous.

Protoconchs in other mimospirids are not well known. The protoconch (internal mold) of the specimen identified as Clisospira sp. by Dzik (Reference Dzik2020) is just over one whorl with a tapered apex, similar in shape and size to the illustrated tapered apex in the specimen attributed to Laeogyra reinwaldti by Frisk and Ebbestad (Reference Ebbestad, Högström, Ebbestad, Wickström and Högström2007, now assigned to Laeogyra sp.). The specimen is ~1.5 mm in diameter, consisting of 1.5 whorls, with the width of the seemingly smooth apex 0.26 mm at the transition to an ornamented teleoconch. Internal molds of L. volhynica Hynda, Reference Hynda1986 and L. alta Hynda, Reference Hynda1986 are each ~1 mm in diameter. The former shows a bulbous initial part, slightly less than 0.2 mm in diameter, followed by a smooth first whorl and then half a whorl with what appears to be impressions of ornamentation. The latter has more whorls, but the bulbous apex is quite similar. Possible impressions of ornamentation appear after approximately two whorls. In all four cases, the width at ~100 μm length from the apex is > 180 μm, indicating that only protoconch 1 is present if using the proxy of Nützel et al. (Reference Nützel, Lehnert and Fýda2006, Reference Nützel, Lehnert and Fýda2007).

It is unclear whether the unusually large protoconch of Catalanispira n. gen. represents a larval shell (protoconch 2) or not, and it is therefore uncertain if it had a nonplanktotrophic or planktotrophic development. The uncoiled, slightly asymmetrical protoconch differs from those known in other mimospirids, regardless of its interpretation, which illustrates the disparity in protoconch morphologies within mimospirids.

Mode of life

An elongated aperture suggests that its axis was subparallel to the long axis of the foot (Linsley, Reference Linsley1977; McNair et al., Reference McNair, Kier, Lacroix and Linsley1981). Alignment of Catalanispira n. gen. in this way and the relatively high angle of inclination of the apertural plane would place the spire slightly inclined to the right and offset posteriorly. Figure 6.2 and 6.8 show the shell in approximately this position. The aperture in Catalanispira n. gen. is described as tangential. None of the available specimens preserve the entire apertural margin of the outer lip, but its growing margin extends quite far adaperturally relative to the inner lip. The arrows in Figure 4.1 and 4.3 show the approximate point where the contact breakage between the whorl and adaxial margin of the outer lip is seen in the holotype. The shape of the outer lip is also evident from growth lines preserved on the upper surface. With the apertural plane parallel to the substratum as outlined above, the position of the shell resembles that of some Silurian pseudophorids, a group with prominently tangential apertures (Wagner, Reference Wagner2002). However, owing to the very deep, funnel-like umbilical area, the apertural plane would not be entirely parallel to the surface, but would extend obliquely into the umbilicus. In shape and function, it would appear similar to the umbilical morphology seen in the mostly sessile, filter-feeding caenogastropods of the family Calyptraeidae (Lamarck, Reference Lamarck1809), among which the umbilical resemblance of the so-called Chinese hat, Calyptraea chinensis (Linnaeus, Reference Linnaeus1758), is a good analogue. Only a few genera in the family have expressed coiling (Collin and Cipriani, Reference Collin and Cipriani2003).

Injuries and disturbances to the shell

Five specimens of Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. show irregularities in growth on the upper surface of the first whorl, and one shows disturbances in growth on the umbilical side. After one whorl in PRI 76977, at a width of 4.6 mm, the apertural outline is marked by a sharp growth line, suggesting a halt in growth (Fig. 4.7). This is also the case in specimens ISGS 1017 and 1019, in which a similar but less pronounced growth halt is evidenced by a more strongly outlined growth line at widths of 5.3 mm and 6.3 mm, respectively (Figs. 6.4, 7.6). In the same position in PRI 76975, at a width of 4.5 mm, the aperture has been broken along nearly the entire margin, creating a large irregular scar stretching subparallel to the apertural edge from close to the upper suture to the periphery (Figs. 5.8, 5.9, 6.1, 6.3). The injury is obscured by the succeeding whorl but probably continues on the umbilical side. Close to the periphery, a crack extends a short distance backward from the edge of the injury. The new shell extends from the fractured edge and its growth is a bit irregular in the area just adapertural to the scar margin, but normal growth is restored shortly thereafter. In the third specimen (PRI 76974), growth is disturbed after half a whorl, as seen by a thickened and irregular section that is only subparallel to the growing edge (Fig. 7.1).

Irregular growth is seen on the umbilical side of the holotype of Catalanispira plattevillensis n. gen. n. sp. (PRI 76973; Fig. 4.3, 4.6). The falcate apertural margin at slightly more than half a whorl back is strongly outlined by a thickened growth line, from which a spiral line continues adaperturally on the surface close to the periphery. It gives the impression of an umbilical carina, but likely results from an irregularity in the growth perhaps from an irritated or injured mantle.

Changes or halts of growth in gastropod shells are sometimes triggered by unfavorable or stressful conditions, but these would introduce a random distribution of such disturbances. The halt in growth observed in four specimens of Catalanispira n. gen. appears at approximately the same size in each individual and could therefore be deterministic. One possibility is that they could mark the transition from a vagile to a sessile lifestyle. Seasonal changes in growth can be excluded, considering the equatorial position of Laurentia in the Katian (Torsvik and Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017). The more obvious shell damage and subsequent repair, coinciding with the halt in growth in specimen PRI 76975, could be attributed to failed predation or abiotic chipping of the shell (e.g., Ebbestad et al., Reference Ebbestad, Lindström and Peel2009; Peel, Reference Peel2015, and references therein).

Conclusion

Mimospirids are an unusual group of mollusks, not only because of their sinistrally coiled shells. The conch morphology, although not well known in many taxa, differs in many respects from that of regular orthostrophic gastropod morphologies by the shapes of the whorl and aperture, the deep umbilicus, and coiling properties. The possible presence of a two-staged protoconch is also highly unusual because this feature is prevalent in advanced gastropods since the mid-Paleozoic (Frýda, Reference Frýda and Talent2012; Nützel, Reference Nützel2014). However, the evidence for mimospirids having a protoconch 2 relies mostly on a few findings in Mimospira, and it may be possible to interpret these differently. An abrupt change in morphology and ornamentation following the embryonic shell seen in a few well-preserved specimens of Mimospira could mark the transition to the teleoconch, in which case only a protoconch 1 is present. Supportive data from a few other mimospirids attributed to Clisospira and Laeogyra, could suggest that they also had only a protoconch 1, but more research is needed.

The new taxon Catalanispira n. gen. from the Ordovician of Estonia and USA is a large mimospirid mollusk. It is placed in Catalanispirinae n. subfam. of the Onychochilidae along with the Lower Ordovician Pelecyogyra from Morocco and France, distinguished by a low trochiform and widely expanding shell, an elongated aperture, a deep funnel-like umbilicus, and an extremely large cap-shaped protoconch.

The protoconch of Catalanispira n. gen. is slightly asymmetrical and seemingly homeostrophic with the teleoconch. In Mimospira, both homeostrophic and heterostrophic protoconchs have been described (Peel, Reference Peel1975; Dzik, Reference Dzik1983; Frýda, Reference Frýda1989). Although well-preserved, it is unclear whether the protoconch in Catalanispira n. gen. represents protoconch 2 or not, but it emphasizes the disparity in protoconch morphologies within the mimospirids.

An elongated aperture suggests that Catalanispira n. gen. had only one gill, and that the aperture was oriented with the long axis subparallel to the axis of the foot. The inclination of the apertural plane further suggests that the spire was tilted slightly backward to the right.

Dextral hyperstrophy (dextrally arranged organs, sinistrally coiled shell) is found in a number of lower Paleozoic gastropods, but it has been argued that the sinistral asymmetry already in the embryonic shell of Mimospira demonstrates sinistral orthostrophy among mimospirids (Dzik, Reference Dzik1983, Reference Dzik, Pályi, Zucchi and Caglioti1999). Lack of conclusive evidence, such as an operculum, and the general problem of establishing hyperstrophy vs sinistral orthostrophy based on the shell alone, also preclude firm conclusions about the nature of shell coiling in mimospirids. Furthermore, the modified concept of a presumed untorted class Paragastropoda, now only including the mimospirids, has undermined the validity of that concept (Frýda et al., Reference Frýda, Nützel, Wagner, Ponder and Lindberg2008; Frýda, Reference Frýda and Talent2012).

Nützel (Reference Nützel2014) expected higher disparity and different forms and clades among early gastropods, and mimospirids could very well represent part of a mainly late Cambrian and Ordovician clade of sinistral mollusks that later went extinct. Whether they are sinistrally coiled gastropods, either hyperstrophic or orthostrophic, or a unique sinistrally coiled gastropod-like mollusk remains unsettled.

Acknowledgments

Four specimens of Catalanispira n. gen. were generously provided by J.A. Catalani of Woodridge Grove, Illinois. Many thanks to H. Bauert, Tallinn, Estonia for information on the original collection site of Öpik (Reference Öpik1930). J.S. Peel, Uppsala, Sweden is thanked for providing insightful comments and discussion on an earlier draft. This paper is a contribution to Project IGCP 653, ‘The onset of the Great Ordovician Biodiversity Event.’ Comments and suggestions from D.M. Rohr, Alpine, Texas and J. Frýda, Prague, are gratefully acknowledged.